Index for Inclusion in Instructional Practice at Elementary Schools

Juang Sunanto

Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia, Bandung, Indonesia

juangsunanto@upi.edu

Keywords: Elementary school, Inclusive classroom, Index for inclusion.

Abstract: The purpose of this study was to measure index of inclusion of the inclusive classrooms in elementary schools

and to examine the teachers’ attitude, perception, and concerns toward the inclusion of children with special

needs in the regular education classrooms. This study used concurrent mixed methods. The participants were

10 elementary school teachers deliberately selected from schools identified as actively implementing inclusive

education programs. The inclusion index was measured through an observation and the teachers’ attitude,

perception, and concerns toward the inclusion of children with special needs were collected through a focus

group discussion. The results revealed that index of inclusion in inclusive classrooms at elementary schools

had not been optimal yet with average of inclusion index amounting to 38.58 of ideal index 48. Teachers have

a positive attitude towards inclusion of children with special needs in regular classrooms. In addition, teachers

have perception that inclusive education is the same as education for persons with disabilities or special

education. Some of the teachers’ primary concerns were implementing different teaching methods, choosing

instructional content to meet the needs of all students, and helping from specialist teacher to handle students

with special needs during instructional practice in the classroom.

1 INTRODUCTION

The Salamanca declaration in 1994 with a

commitment to Education for all brought the idea of

Inclusive education to the forefront of the

International scenario. According to the declaration,

inclusive education means the inclusion of all

children in all class-room and out-of-class room

activities, which implies that all children should have

equal opportunities to reach their maximum potential

and achievement, regardless of their origin and

abilities or disabilities, and regardless of their

physical, intellectual, social, emotional, or linguistic

differences (UNESCO, 1994; Stubbs, 2002;

Frederickson and Cline, 2009).

Implementations of inclusive education at

elementary schools have reported by only few

(Sucuoglu, Akalin, and Pınar, 2014). Hence,

questions on how far its implementation in Indonesia

should get attention. Some researchers investigated

implementation inclusive education in elementary

schools, for example, Lee et al. (2010) and Berry,

(2010) investigated implementation of inclusive

education in elementary schools. Thurlow et al.

(1984) and Golis (1995) investigated the instructional

characteristics of inclusive classrooms. However,

there were few studies regarding to evaluation of the

implementation of inclusive education in schools

during instructional process.

The main problem of this study was to explore

issues concerning with how to evaluate values of

inclusive education happened in instructional

processes at elementary schools. Therefore, this

study was carried out using descriptive study and the

purpose of the study was to measure index of

inclusion of the inclusive classrooms in elementary

schools and to investigate the teachers’ attitude,

perception, and concerns toward the inclusion of

children with special needs in the regular education

classrooms.

2 METHODS

This study used concurrent mixed methods to

measure index of inclusion and to examine the

teachers’ attitude, perception, and concerns toward

the inclusion of children with special needs. The

participants of the study were ten elementary school

teachers. There were five teachers of elementary

private schools and five of those public elementary

schools. They were six female and four male teachers

508

Sunanto, J.

Index for Inclusion in Instructional Practice at Elementary Schools.

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Educational Sciences (ICES 2017) - Volume 2, pages 508-512

ISBN: 978-989-758-314-8

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

ranging in age from 35 to 55 years. The teachers were

selected from ten elementary schools in Bandung City

which were identified to actively implement inclusive

education programs.

The data were collected through observation and

focus group discussion. An observation guide

developed by Centre for Studies on Inclusive

Education (Booth and Ainscow, 2002; Booth,

Ainscow, and Kinston, 2006) was used to measure

index of inclusion in the process of instruction. The

index of inclusion is a number showing how far

inclusion practices occurred in instructional

processes. To measure the index, the participants

were asked to teach three different subjects in the

inclusive classrooms. During teaching-learning

process, the participants were rated by using the

observation guide consisting of sixteen indicators.

Each indicator was rated using a scale from 0 to 3.

The score of 0 indicated less inclusiveness where the

inclusive instruction was not at all identified.

Meanwhile, the score of 3 showed greater

inclusiveness where the inclusive instruction was

clearly identified. The total score ranged from 0 to 48.

In addition, a focus group discussion was used to

investigate teachers’ attitudes, perceptions, and

concerns toward inclusion of students with special

needs. There were ten questions were used in the

discussion.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

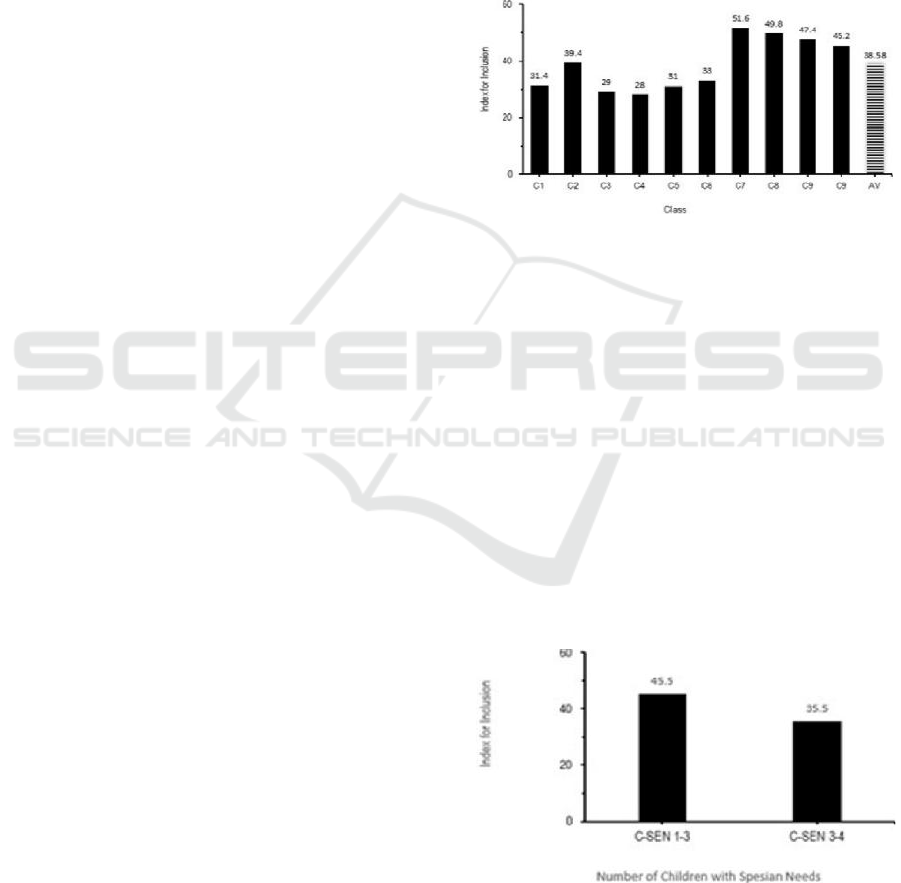

Figure 1 is index of inclusion achieved in the

instructional process of ten classes at elementary

school. The data shows that the highest index of

inclusion is 45.6 and the lowest is 28 with average

37.16 of ideal index 48. Index of inclusion is a

number that shows the inclusiveness happened in an

instructional process in the classroom. Therefore, a

class that has a high index of inclusion indicates that

the values of inclusiveness much happening in the

instructional process in the classroom. Index of

inclusion in the class 7 is higher than in other classes.

It indicates that the values of inclusivity in class 7

appeared more often than in any other class.

Inclusiveness occurring in an instructional process is

highly dependent on the performance of a teacher

who is doing instructional. Inclusiveness performed

by teachers during the instructional process in a

classroom can be influenced by many factors, such as

attitudes of teachers towards inclusive education, the

experience of teachers to deal with the children with

special needs, the ability of teachers to manage

classes and others.

One of the characteristics of the inclusive classroom

is that teachers are able to manage a class effectively

and all students can participate in the learning

process. There are several key practices that were

important contributors to meeting the needs of all

students in inclusive school, for example, teachers

have high expectations for behavior of all students

and students with special needs are supported as a

natural or ordinary part of support that is provided for

all students (McLeskey, Waldron, and Redd, 2014).

Figure 1: Index for inclusion for each class and average.

Figure 2 shows that index of inclusion of a class

that has 2-3 students is 45.5 while a class that has 4-5

students is 35.5. Index of inclusion of classes with

more number of children with special needs is lower

than those of less number of children with special

needs. It indicates that index of inclusion increased as

a result of the number of children with special needs

in a class decreased. Teachers will face some

difficulties to manage students’ behavior when there

were many students with special needs as well as

students without special needs in the classroom.

Vaughn (1996) mentioned one of several aspects

which might cause teachers difficult to improve

inclusiveness was the large number of students with

special needs in the class.

Figure 2: Index for inclusion as a function of number of

students with special needs in each class.

Index for Inclusion in Instructional Practice at Elementary Schools

509

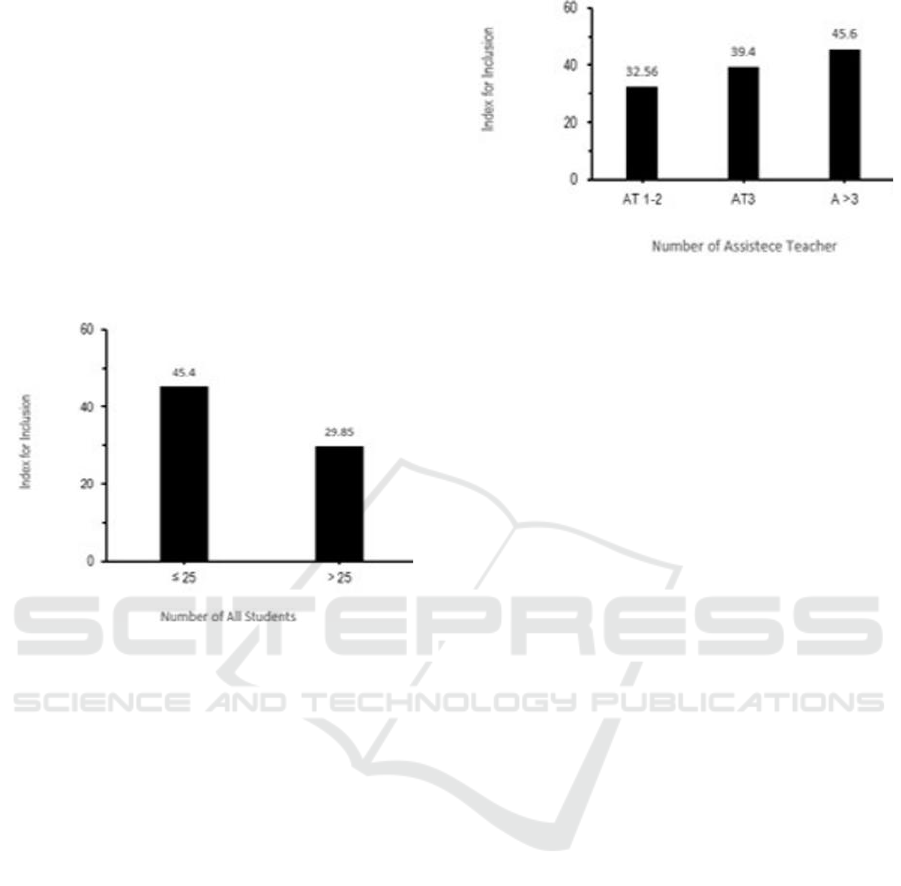

Figure 3 shows index of inclusion of a class have

same or less than 25 students is 45.4 while a class that

has 25 students or more is 29.85. This data reveals

that a class with more students cause inclusion index

becomes lesser. In the classes having much number

of students, the main teachers of inclusive classroom

are not able to pay attention to the regular students as

well as students with special needs optimally.

According to Odongo and Davidson (2016) there

were some important issues identified in their study

regarding large class sizes, teacher training, student

needs and resources are particularly important for

inclusive practices to be successful.

Figure 3. Index for inclusion as a function of total number

of students in each class.

Figure 4 shows index of inclusion of a class that

have teacher assistant more than 3, 3, and 1 to 2 is

45.6, 39.4, and 32.56 respectively. It indicates that

the existing of the teacher assistant in the inclusive

class could increase inclusion index. It should be

noted that inclusive education would best be achieved

if appropriate supports were available to assist the

teachers and learners in inclusive rooms (Kristensen,

Omagor-Lican, and Onen, 2003; Dupoux, Wolman,

and Estrada, 2005). Collaboration between the

mainstream and the special education teachers is

important and that there should be a clear guideline

on the implementation of inclusive education. When

implementing inclusive education in regular

classrooms, teachers are confronted with various

problems that require many types of support. Teacher

assistant or specialist teacher, resource teachers and

resource rooms are one emerging form of support

services in regular schools (Xiaoli and Olli-Pekka,

2015).

Figure 4. Index for inclusion as a function of number of

teacher assistant in each class.

In general, the teachers have a positive attitude

towards inclusive education. It is believed that

teachers and their attitudes toward inclusion are very

important variables in the implementation of

successful inclusive practices (Avramidis and

Norwich, 2002; Parasuram, 2006). Teachers who

have favorable attitudes toward inclusion generally

believe that students with disabilities belong in

general education classrooms, that they can learn

there, and that the teachers have confidence in their

abilities to teach students with disabilities (Berry,

2010).

In general, an elementary school teacher has

perception that inclusive education is the same as

education for persons with disabilities or special

education. Actually, inclusive education was the

education that providing appropriate responses to the

broad spectrum of learning needs in formal and non

formal educational settings (UNESCO, 2003). It

indicated that achievement of an inclusive education

system is a major challenge facing countries

throughout the world (Meynert, 2014; Elton-

Chalcraft, Cammack, and Harrison, 2016).

The data shows some of the teachers’ primary

concerns were implementing different teaching

methods, choosing instructional content to meet the

needs of all students, and helping from specialist

teacher to handle students with special needs during

instructional practice in the classroom. In the

inclusive teaching-learning practices, most of regular

teachers face challenges with respect to the diversity

of characteristics, abilities, and learning needs of the

students, because they do not have competence to

handle students with special needs. It believed that

inclusion is more likely to be successful when the

class teacher takes a central role in the teaching-

learning process. In addition, the outcomes of

inclusion are strongly influenced by the ways in

which the specialist teacher works together with the

class teacher (Sam Fox and Davis, 2004).

ICES 2017 - 1st International Conference on Educational Sciences

510

In many countries, there is an increasing

educational trend towards full inclusion, meaning that

every child, disabled or not, should be taught in a

regular classroom. The need to provide learning

environments that respond to individual differences

has been a longstanding concern. Index of inclusion

is one way to evaluate the implementation of

inclusive education in schools during instructional

process. The present study evaluated the inclusive

index using 18 observational items developed by

Ainscow so that there were some inclusivity values

during the teaching-learning process could not be

revealed. Additional research is needed to develop

observational items of the inclusive index. Moreover,

future investigation should use comprehensive

observational item more suitable with the condition

of teaching learning in Indonesia.

4 CONCLUSION

Indexs of inclusion achieved by the elementary

schools amounting to 38.58, whereas ideal inclusion

index is 48. It shows that achievement of index of

inclusion in the instructional practice can be

influenced by number of student with special needs,

total number of students, number of teacher assistant,

and teachers’ experience in attending training on treat

children with special needs. In general, the

elementary teachers have a positive attitude towards

inclusive education and they agreed that inclusive

education should be implemented in the elementary

schools. Some of the teachers’ primary concerns were

implementing different teaching methods, choosing

instructional content to meet the needs of all students,

and helping from specialist teacher to handle students

with special needs during instructional practice in the

classroom.

REFERENCES

Avramidis, E., Norwich, B. 2002. Teachers’ attitudes

towards integration/inclusion: A review of the

literature. European Journal of Special Needs

Education, 129-147.

Berry, R. A. 2010. Pre-service and early career teachers’

attitudes toward inclusion, instructional

accommodations, and fairness: Three profiles. The

Teacher Educator, 45, 75-95.

Booth, T., Ainscow, M. 2002. Index for inclusion

developing learning participation in schools. London:

The Center for Studies on inclusive Education (CSIE).

Booth, T., Ainscow, M., Kinston, D. 2006. Index for

inclusion developing play, learning, and participation

in early and years and childcare. The Center for Studies

on Inclusive Education.

Dupoux, E., Wolman, C., Estrada, E. 2005. Teachers'

attitude toward integration of students with disabilities

in Haiti and the United States. International Journal of

Disability, Development and Education, 52(1), 43-58.

Elton-Chalcraft, S., Cammack, P. J., Harrison, L. 2016.

Segragation, integration, inclusion and effective

provision: A case study of perspectives from special

educational needs children, parents and teachers in

Bangalore India. International Journal of Special

Education, 31(1), 2-9.

Frederickson, N., Cline, T. 2009. Special Education Needs,

Inclusion and Diversity (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-

Hill Education.

Golis, S. A. 1995. Inclusion in elementary schools: A

survey and policy analysis: A peer-reviewed scholarly

electronic journal, education policy analysis archives.

Journal of Special Education, 48, 59-70.

Kristensen, K., Omagor-Lican, M., Onen, N. 2003. The

inclusion learners with barriers to learning and

development into ordinary school setting: A challenge

for Uganda. British Journal of Special Education, 30,

194-201.

Lee, S. H., Wehmeyer, M. L., Soukup, J. H., Palmer, S. B.

2010. Impact of curriculum modifications on access to

general education curriculum for students with

disabilities. Exceptional Children, 76(2), 213-233.

McLeskey, J., Waldron, N. L., Redd, L. 2014. A case study

of a highly effective, inclusive elementary school. The

Journal of Special Education, 48(1), 59-70.

Meynert, M. J. 2014. Inclusive education and perceptions

of learning facilitators of children with special needs in

a school in Sweden. International Journal of Special

Education, 29(2), 1-18.

Odongo, G., Davidson, R. 2016. Examining the attitudes

and concerns of the Kenyan teachers toward the

inclusion of children with disabilities in the general

education classroom: A mixed methods study.

International Journal of Special Education, 32(2), 1-

18.

Parasuram, K. 2006. Variables that affect teachers' attitudes

towards disability and inclusive education in Mumbai,

India. Disability & Society, 21(3), 231-242.

Sam Fox, P. F., Davis, P. 2004. Factors associated with the

effective inclusion of primary-aged pupils with down’s

syndrome. British Journal of Special Education, 31(4),

184-190.

Stubbs, S. 2002. Inclusive education where there are few

resources. Oslo: The Atlas Alliance.

Sucuoglu, N. B., Akalin, S., Pınar, E. S. 2014. Instructional

variables of inclusive elementary classrooms in Turkey.

International Journal of Special Education, 29(3), 40-

57.

Thurlow, M. Y., Graden, J., Algozzine, B. 1984. What'

"special" about the special education resorce room for

learning disabled students? Learning Disabilities

Quarterly, 6, 283-288.

UNESCO. 1994. The salamanca statement and framework

for action on special needs education world conference

Index for Inclusion in Instructional Practice at Elementary Schools

511

on special needs: Access and quality.. Salamanca,

Spain: Ministry of Education and Science Spain and

UNESCO Publication.

UNESCO. 2003. Overcoming exclusion throug inclusive

approaches in education a chalengge & a vision:

Conceptual paper. Paris: UNESCO

Vaughn, S. S. 1996. Teachers views of inclusion. Learning

Disabilities Research & Practice, 11, 96-1006.

Xiaoli, X., Olli-Pekka, M. 2015. Teacher views of support

for inclusive education in Beijing, China. International

Journal of Special Education, 30(3), 150-159.

ICES 2017 - 1st International Conference on Educational Sciences

512