Communication and Students' Needs

Measuring Students' Affect toward Teaching and Learning Process in Higher

Education

Ridwan Effendi

and Vidi Sukmayadi

Communications Department, Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia, Street. Dr Setiabudi No.229, Bandung Indonesia

{reffendi09, vsukmayadi}@upi.edu

Keywords: Affective Learning, Instructional Communication, Interpersonal Communication, Teacher Evaluation.

Abstract: In achieving successful learning outcomes, educational systems should be able to fulfill not only students'

academic needs but also their personal and interpersonal needs. To meet the students' needs, an effective and

affective communication must be employed in the teaching and learning process. In the current study, the

authors measure students' affect in regard to their affective learning experience and their evaluation toward

their teachers while studying in the university. Surveys were used to collect the students' affect from 886

students in eight faculties at Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia. The following results were yielded from the

data: (1) six out of eight faculties indicate a high affective learning level; (2) In terms of teachers/instructors

evaluation, most students from all faculties have a high level of appreciation to their teachers' instructional

communication; (3) In addition, the faculty of Art and Design Education received the highest rate on their

students' affect. The study is expected to contribute in providing initial data for developing an affective based

learning program.

1 INTRODUCTION

Nowadays, the term “affective” have been introduced

and applied as a part of students’ learning process. As

described by Bloom (1964), The affective domain

describes the emotional processes of learning,

focusing on the learners’ emotional states, values,

motivations, attitudes and characters. In line with this,

Smith and Ragan (in Jagger, 2013) identify affective

characteristics as expressed by statements of

opinions, beliefs or an assessment of worth. When the

affective aspects are embbeded into the education

system, it becomes a set of learning process that

concern with learners’ social-individual

development, feelings, emotions, morals, ethics

(Beane, 1990).

These aspects should not been neglected from the

curriculum. The inclusion of affective components

within the learning process can enhance the whole

student rather than merely focusing upon cognitive

development. In supporting this, a research conducted

by Ferguson (2006) on primary education students

proved that when school curriculum focuses solely

upon the cognitive realm, the uneven development of

the other domains may be enhanced, thus

emphasizing the child’s feeling of being ‘out of sync’

with his or her peers. From this the authors believe

that educators need to incorporate strategies aimed at

balancing the affective and cognitive learning aspects

for a balanced educational outcome.

One important strategies in fulfilling the students

affective needs is through interpersonal

communication between teachers and their students.

Most teachers attempt to satisfy the academic needs

of the students. They feel an educational commitment

or obligation to fulfil these needs, but other student

needs such as affective needs often are neglected.

However some teachers try to communicate with their

students to assist them to satisfy their personal and

interpersonal needs. They have been aware that if a

student’s personal and interpersonal needs are not

met, the academic needs may never be met either

(Richmond, Wrench, & Gorham, 2009).

From the aforementioned rationales, This paper

attemps to measure how students affectively feel to

the learning process that they have experienced in the

classroom. It is expected that the results of students’

affective level and their evaluation toward their

teachers can serve as a basis in determining future

Effendi, R. and Sukmayadi, V.

Communication and Students’ Needs - Measuring Students’ Affect toward Teaching and Learning Process in Higher Education.

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Sociology Education (ICSE 2017) - Volume 1, pages 511-515

ISBN: 978-989-758-316-2

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

511

learning contents that can satisfy both cognitive and

affective needs of the students.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

The current study focuses on students’ affect and

teacher evaluation. In this part the authors would like

to review some references and other works related to

the study.

2.1 Affective Learning

As previously mentioned, Affective domains are

more often associated with a taxonomy introduced

first by Karthwohl, Bloom, and Masia (1964). It is

called affective taxonomy because it is based on the

principle of internalization between both behaviors

and values in an individual. This Internalization is the

basic concept for understanding the taxonomy

because the more values and attitudes are internalized

the more it affects one's behavior.

These values and attitudes components then were

categorized by them into five levels of hierarchical

taxanomy. They are ranged from receiving

(awareness or willingness to attend to an instructional

message), responding (willingness to respond and/or

actively engage instruction), valuing (seeing the

significance of a particular behaviour, idea, object, or

phenomenon, organizing (comparing and contrasting

competing value systems in an effort to relate and

synthesize values), and characterization by a value or

value set (value system, characteristic life style).

The set of categories was the underlying support

for the authors in the current study to measure the

affective learning experienced by the students. As

mentioned by , (Thweatt & Wrench, 2015) Affective

learning should be viewed as multidimensional with

a series of measures that tackle various aspects of the

construct and should also cover the internal value

changes that persist long after the learning event

occurs. Moreover it should be clear then that students’

affective experiences in the classroom impact their

subsequent behaviours, perceptions, and outcomes in

important ways. Thus, despite not measuring

affective learning itself, the assessment of students’

affective experiences serves to operationalize an

important variable for investigation (Bolkan, 2015).

Based on these assumptions, the authors then conduct

the study by measuring the affective learning based

on the students perception toward their learning

experience.

2.2 Teacher Evaluation

This study also take teachers or lecturers performance

as the center of attention. In this case, the students

affect toward their teachers/lecturers is measured.

One of the reasons to include teachers’ performance

as part of the measurement is that a teacher is a

prominent stakeholder in the learning process. That

is why in order to improve student learning, an

evaluation becomes a must for improving teacher

practice.

As argued by Goe and Little from the National

Education Association (2017), the core purpose of

teacher assessment and evaluation should be to

reinforce the knowledge, skills, emotions, and

classroom practices of professional educators. This

goal serves to promote student growth and learning

while also inspiring great teachers to remain in the

classroom.

Teachers need to be evaluated to see the teacers

performance and how they can relate to their students

affectively. Evaluation concerns itself with more than

how well a teacher teaches. It is also about how a

teacher works with the classes of students that make

up a teacher’s teaching assignments. Teaching also

concerns itself with the rapport a teacher has with the

whole class, and not just with those in the class who

understand and comport themselves in the manner

thought by the teacher to be most appropriate

(Coulombe, 2011).

In other words, a teacher’s responsibilities should

include respect for all students, attention to best

teaching practices, and dedication to the cause of

teaching all of the students in class so that they will

achieves mastery.

2.3 Related Studies

Numerous previous studies indicate that affective

component and teachers communicating style are two

of the most influencing factors in fulfilling the

students’ needs in any level of education including in

a higher education setting.

The authors initial study on freshmen students

communication anxiety indicates that one of the

factors that can ease their anxiety is the teachers

interpersonal skills (Effendi & Sukmayadi, 2016).

The study analyzed fresmen students communication

apprehension from 11 departments. The conclusion

showed that one of the important factors aside from

having a suitable academic environment is the

fulfillment of students' affective needs.

In case of affective learning measurement, a team

of researcher from Texas Shave analyzed how

ICSE 2017 - 2nd International Conference on Sociology Education

512

affective domain can be measured using writing

assessment. He employed content analysis of 83

reflective writing samples was used to analyze

affective learning at the levels of receiving,

responding, valuing, organization, and

characterization University (Barry L, Kim, and

Felton, 2006. The results indicated that that some

students expressed affective learning at higher levels

of the affective taxonomy and increased their level of

reflective writing in the process.

In addition, Smith, Mann and Shephard (2011)

argued that the affective assessment should consist of

the abilities categorization (to receive, to respond, to

value, to organise and to internalize) provides an

excellent and forward-looking framework within

which to explore the measurement of affective

attributes. Related to the current study, the authors

will analyze not only the student’s affective domain

but also evaluate the teachers performance based on

the students perspective.

3 METHODS

The study is quantitative by nature and the authors

have employed survey method in collecting the data.

The sample consist of 886 undergraduate students in

Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia (Indonesia

University of Education or UPI). The samples were

randomly selected to take the survey from all eight

faculties in the university. The faculties are Faculty of

Education Science (FIP), Faculty of Social Science

Education (FPIPS), Faculty of Languages and

Literature Education (FPBS), Faculty of Mathematics

and Natural Science Education (FPMIPA), Faculty of

Technology and Vocational Skills Education (FPTK),

Faculty of Economics and Business (FPEB) and

lastly, the Faculty of Arts and Design Education

(FPSD). All students voluntarily participated in the

study.

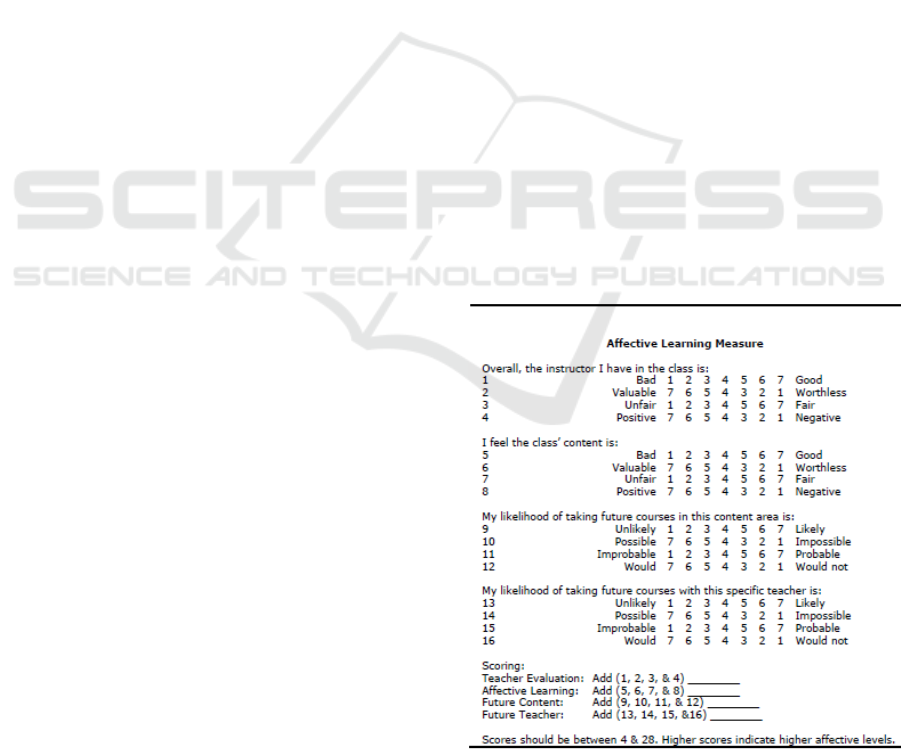

In analyzing the data the authors used the

affective learning and teacher evaluation assessment

scale developed by McCroskey, J. C. (1994). The

instrument consist of 16 items. It has four categories

(each with four bipolar scales). The four measures

are; (1) Affect toward content measures, (2) Affect

toward classes for students in this content, (3) Affect

toward instructor measure, (4) Affect toward taking

courses with the specific instructor. As emphasized

by McCroskey (1994), the first two measures can also

be applied together as a measure of affective

Learning. In similar fashion, the third and fourth

measures can be jointly used as a measure of

Instructor Evaluation. The instrument was distributed

to the students, and they circled the number on each

items that best represent their feelings.

All of the categories were assessed and in

computing score on the measures, the authors used

the scoring formula by McCroskey (1994) after the

total score is collected for each of the measures, the

next step is scoring for affective learning and

instructor evaluation. The affective learning score is

resulted from summing up the total score of "affect

toward content" and "affect toward classes in the

particular content". Then, for the teacher evaluation,

the score is obtained from summing up "Affect

toward instructor" and "Affect toward taking classes

with this instructor". The final score is ranged from

20 (bad) to 85 and above (Very Good).

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The McCroskey (1994) instrument measures

students’ attitudes toward (1) instructor of the course

(teacher evaluation), (2) content of the course

(affective learning), along with measures of higher

order levels of student affect, (3) taking additional

classes in the subject matter, and (4) taking additional

classes with the teacher. Dimensions two and three

are in line with Krathwohl, Bloom, and Masia’s

(1956) conceptualization of the affective domain in

learning while dimensions one and four represent

teacher evaluation. The following figure 1 is the

measure of affective learning.

Figure 1: Affective learning measure.

Communication and Students’ Needs - Measuring Students’ Affect toward Teaching and Learning Process in Higher Education

513

Regarding to the current study, the results of the

initial affective measurement are described in the

following table 1:

Table 1: Measuring results.

Faculty Toward

Content

Toward

Teacher

Future

Content

Future

Teacher

FIP

20.38 18.34 22.46 18.34

FPIPS

23.4 16.5 24 18.2

FPBS

22.53 16.23 26.32 18.03

FPEB

22 12.77 22.5 16.59

FPOK

24 12.27 24.62 17.76

FPMIPA

21.53 19.31 22.66 19.83

FPTK

22.23 16.45 23.68 19

FPSD

22 23.33 26.5 20

The table represents the partial score based on the

four categories. It can be seen that in terms of students

affect toward the class content, the faculty of sport

science (FPOK) got the highest score by 24. While

the faculty of Arts and design (FPSD) achieved the

highest rank for students affect toward their

instructors.

However, as mentioned previously, the scoring

for affective learning and teacher evaluation is

separated. The score above is the partial score. It does

not mean that the faculty with the highest score get

the highest affective learning level.

Upon computing the partial score, the scoring of

teacher evaluation and affective learning can be then

calculated. The sum of "affect toward content" and

"affect toward classes in the particular content" is for

the affective learning score. Furthermore, the total

sum of "Affect toward instructor" and "Affect toward

taking classes with this instructor" recorded as the

score for teacher evaluation. The result of the

calculation can be seen in the next table 2.

Table 2: Affective learning and teacher evaluation.

Faculty Affective

Learning

Teacher

Evaluation

Sum

FIP

42.84 36.68 79.52

FPIPS

47.4 34.7 82.1

FPBS

48.85 34.26 83.11

FPEB

44.5 29.36 73.86

FPOK

48.62 30.03 78.65

FPMIPA

44.19 39.14 83.33

FPTK

45.91 35.45 81.36

FPSD

48.5 43.33 91.83

In determining the overall score, all of the two

subscores were added and the scoring range should be

between 30 and 100 with the following interpretation:

a) Scores between 83 and 100 indicate a high

level of students affect.

b) Scores between 55 and 83 indicate a moderate

level of students affect.

c) Scores between 30 and 55 indicate a low level

of students affect.

According to the results derived from the

Affective learning and teacher evaluation

measurements, it can be seen that most of the faculty

scored a moderate level of students affect. Five out

of the eight faculties received a score which range

from 73.86 (FPEB) to 82.10 (FPIPS).

In spite of the moderate rank achieved by the

faculty of economics and business education (FPEB),

they got the lowest score among the other faculties.

This is due to the low score of student affect toward

their lecturers. As suggested by Richmond, Wrench,

and Gorham (2009), when the instructors' control,

social, and affection performance are not met the

student’s intellectual, academic, and interpersonal

communication skills, the student affect toward the

class might suffer.

Moving on to the higher rank of the measurement

scores, it is noticeable that the faculty of arts and

design education (FPSD) gets the highest score with

91.83.

While the score for the faculty of mathematics and

Science education (83.33) is roughly equal to that of

the faculty of language education and literature

(83.11). What is interesting with FPSD, although

they did not gain the highest score in affective

learning rank, their students affect toward the

lecturers is much higher than the other faculties.

Thus, this study suggest that teachers’

performance play a significant role in developing a

more affective learning. All of the faculties in the

high level cluster are also contributed by the high

students’ appreciation toward their lecturers.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Overall, the measure is beneficial to determine how

students affectively feel in our classroom. A good

learning system along with the lecturers’ competent

interpersonal skills proved to be the key factor in

shaping a suitable affective learning.

It is also expected that the study can contribute in

providing useful initial data for higher education

institutions to develop a learning program focusing on

affective learning. Moreover the measurement can

also be employed as an instrument for evaluating the

teachers or lecturers performance.

For further research, the authors suggest to

elaborate more on the topic of why they perceived

that why toward the class content and the lecturers. It

ICSE 2017 - 2nd International Conference on Sociology Education

514

is suggested that the results can be used as the starting

point to conduct a qualitative study to explore the

subtle meanings beyond the students’ responses.

Finally, students who feel their teachers as able to

satisfy some of their affective needs are tend to be

more satisfied with their lecturer, the course, and

eventually the university as a whole.

REFERENCES

Barry L, B., Kim, D., Felton, S. 2006. Measuring Learning

in the Affective Domain Using Reflective Writing

about a Virtual Agricultural Experience. Journal of

Agricultural Education, 24-32.

Beane, J. 1990. Affect in the Curriculum: Toward

Democracy, Dignity, Diversity. New york: Columbia

University.

Blume, D. B., Baldwin, T., Ryan, C. K. 2013.

Communication Apprehension: A Barrier to Students'

Leadership, Adaptability, and Multicultural

Appreciation. Academy of Management Learning and

Education Vol 2, 158–172.

Bolkan, S. 2015. Students’ Affective Learning as Affective

Experience: Significance, Reconceptualization, and

Future Directions. Communication Education, 502 -

505.

Coulombe, G. 2011. minutemannewscentre. Retrieved from

http://www.minutemannewscenter.com/fairfield/why-

teacher-evaluations-are-important-to-both-successful-

and-unsuccessful/article_50c11480-b531-51a9-be87-

f1c135213879.html

Effendi, R., Sukmayadi, V. 2016. Communication

apprehension levels of tourism and social sciences

students. Proceedings of the 3rd International

Hospitality and Tourism Conference, IHTC 2016 and

2nd International Seminar on Tourism, ISOT 2016.

Bandung: CRC Press.

Ferguson, S. A. 2006. A case for affective education:

Addressing the social and emotional needs of gifted

students in the classroom. Virginia Association for the

Gifted Newsletter,, pp. 1-3.

Goe, L., Little, O. 2017. National Education Association.

Retrieved from www.nea.org:

http://www.nea.org/assets/docs/Teacher_Evaluation_

Measures_and_Systems.pdf

Jagger, S. 2013. ffective learning and the classroom debate.

Innovations in Education and Teaching International.

Krathwohl, D. R. 1964. Taxonomy of educational

objectives: The classification of educational goals.

Handbook II: Affective domain. New York: Longman.

McCroskey, J. 1994. Assessment of affect toward

communication and affect toward instruction in

communication. summer conference proceedings and

prepared remarks:Assessing college student

competence in speech communication. Annandale, VA:

Speech Communication Association.

Richmond, V., Wrench, J. S., Gorham, J. 2009.

Communication, Affect, and Learning in. Tapestry

Press.

Thweatt, K. S., Wrench, J. S. 2015. Affective Learning:

Evolving from Values and Planned Behaviors to

Internalization and Pervasive Behavioral Change.

Communication Education Vol. 64, No. 4, 497-499.

Communication and Students’ Needs - Measuring Students’ Affect toward Teaching and Learning Process in Higher Education

515