Explicit Correction in Scaffolding Students: A Case of Learning

Spoken English

Friscilla Wulan Tersta and Wawan Gunawan

Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia, Bandung, Indonesia

friscillawulant@gmail.com, wagoen@upi.edu

Keywords: Explicit Correction, Corrective Feedback, Scaffolding.

Abstract: This study attempted to portray the potential of oral corrective feedback, especially explicit correction as one

of the dominant types used by the teacher in teaching the students who learn spoken English. Oral corrective

feedback has been often considered as a correcting tool for students’ errors. Most of the previous studies

which investigated oral corrective feedback found that recast is the most common type used by the teacher in

which it was an opposite from the result of this study. It is essential to know the types of oral corrective

feedback used by the teacher, as a functional English model, to help the students develop their own capacity

in learning. This study used qualitative method. One English teacher and 39 students were involved in this

study. The data were collected by classroom observation, interview, and teacher’s document. The data were

then analyzed, described, and interpreted comprehensively. The result of this study revealed that explicit

correction was the most frequently used corrective feedback from the teacher in the classroom. Correcting by

giving motivation and emphasizing on students’ error was claimed as the teacher’s strategy in scaffolding the

students in learning English.

1 INTRODUCTION

Speaking is claimed as one of the pivotal skill that

should be achieved and mastered for language

learners. According to Derakhsan, Khalili, and

Baheshti (2015) as cited in Derakhsan et al. (2016),

the past four decades have witnessed the rapid

development of speaking skill in second language

learning because speaking plays an important role in

learners’ language development

Indonesian learners still consider speaking to be

one of the most challenging skills to be acquired.

Speaking is an even more problematic skill to be

mastered by foreign language students (Al-Saadi,

Tonawanik, & Al-Harthy, 2013). Indeed, some

frustration commonly voiced by learners is that they

have spent years studying English, but still they

cannot speak it.

Students remain to make mistakes which may lead

to get error fossilized (see Harmer, 2001). According

to Martinez (2006), in order to lead students to be

aware of some errors, learners need to receive

comprehensible input from teachers who can help

them improve their competence and performance. In

a similar vein, Lengkanawati (2017) argues that

teacher as a facilitator in the classroom should let the

students involved in the process of learning itself to

give them an autonomous learning experience.

One of the strategies to scaffold the students is

providing feedback as comprehensible input for

students. There are several strategies in providing

feedback, such as evaluative feedback and interactive

feedback (Cullen, 2002; Richard & Lockhart, 1996 as

cited in Ran & Danli, 2016). The feedback given by

the teacher may contribute to developing students’

capacity or may only correct students’ error to help

students complete the task (Thompson, 2010).

The most common feedback that teachers usually

employ in their teaching is corrective feedback

(Fawbush, 2010). Hen (2008, as cited in Méndez &

Cruz, 2012) suggests that corrective feedback is a

more general way of providing some clues, or

eliciting some correction, in addition to the direct

correction made by the teacher. Moreover, corrective

feedback can push the students to modify their faulty

utterances (Swain in Lowen & Reinders, 2011) and

prevent fossilization (Gass, 1991; Mendez & Cruz,

2010). Corrective feedback is defined as a teacher’s

reactive move that invites the learners to attend to the

grammatical accuracy of the utterance which is

produced by the learner (Sheen, 2007).

Tersta, F. and Gunawan, W.

Explicit Correction in Scaffolding Students: A Case of Learning Spoken English.

DOI: 10.5220/0007163701530159

In Proceedings of the Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference

on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education (CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017) - Literacy, Culture, and Technology in Language Pedagogy and Use, pages 153-159

ISBN: 978-989-758-332-2

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

153

Previous research has investigated about oral

corrective feedback in educational setting and most of

the result found that Recast was the most dominant

type among the other types of corrective feedback

(Subekti, 2016; Fajriah 2015; Bhuana, 2014; Maolida

2013).

Based on the preliminary investigation, it was

found that the teacher in one of the best schools in

Bandung Barat regency tended to use explicit

correction in indicating the students’ errors in the

classroom. To expand on the existing types of

corrective feedback, this study focuses on exploring

the potential of corrective feedback, specifically

explicit correction, to scaffold students in their

learning spoken English.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Corrective Feedback

More recently, according to Beuningen (2010), Ellis

(2009), Ellis et al. (2006), and Li (2010), corrective

feedback is the teacher’s responses to the students’

erroneous second language production. According to

Calsiyao (2015) “oral corrective feedback is a means

of offering modified input to students, which could

consequently lead to modified output by the

students”(p. 395). Likewise, Chaudron (1997, as cited

in Mendez & Cruz, 2012) defines “oral corrective

feedback as any reaction of the teacher, which clearly

transforms, disapprovingly refers to, or demands

improvement of the learner utterance”(p. 64).

2.1.1 Types of Corrective feedback

Recast: “A recast is a reformulation of the learner’s

erroneous utterance that corrects all or parts of the

learner’s utterance and is embedded in the continuing

discourse” (Sheen, 2011, p. 2).

Explicit correction refers to the explicit provision

of the correct form (Lyster & Ranta, 1997) or the clear

indication of error made (Kagimoto & Rodger, 2007).

Repetition is defined as the teacher’s repetition, in

isolation, of the students’ erroneous utterance (Lyster

& Ranta, 1997).

Clarification request is defined as a way to

indicate to the students that their utterance has been

misunderstood by the teacher or that the utterance is

ill formed in some way and that a repetition is

required (Lyster & Ranta, 1997; Ellis, 2009;

Kagimoto & Rodger, 2007; Surakka, 2007 as cited in

Rezaei et al., 2011).

Elicitation is a correction technique that prompts

the students to self-correct (Panova & Lyster, 2002;

Lee, 2013) by pausing, so the student can fill in the

correct word of phrase (Lee, 2013), and may be

accomplished in one of the three following ways

during face-to-face interaction, each of which vary in

their degree of implicitness or explicitness (Panova &

Lyster, 2002).

Metalinguistic feedback refers to comment,

information, or question related to the well-

formedness of the students’ utterance, without

explicitly proving the correct form (Lyster & Ranta,

1997; Panova & Lyster, 2002).

Paralinguistic signal, or known as body language

(Ellis, 2009; Mendez & Cruz 2012), is defined as

gesture or facial expressions used by the teacher to

indicate that the students’ utterance is incorrect (Ellis,

2009; Mendez & Cruz, 2012).

2.2 Scaffolding in Educational Setting

There are many definitions which define scaffolding

in educational context. Many theories outline that

scaffolding is the temporary framework for learning.

According to Lawson and Linda (2002) state that the

strategy of the scaffolding can be appropriately done

if the teacher encourages the learners to develop their

initiative, motivation, and resourcefulness. Moreover,

Hammond and Gibbons (2001) also argue that

scaffolding is classified as a term of temporary

supporting structures. According to them, teachers

need to assist learners to develop new understandings,

new concepts, and new abilities. As the learner

develops control of these, so teachers need to

withdraw that support, only to provide further support

for extended or new tasks, understandings and

concept.

In addition, Maybin, Mercer, and Stiere, (1992)

also assert that scaffolding in the context of classroom

interaction is defined as the "temporary but the

essential nature of the mentor's assistance", in which

the teacher supporting learners to carry out tasks

successfully, so that they later will be able to

complete similar tasks alone.

In the process of scaffolding, the teachers help the

students in mastering a task or lesson that the students

are initially unable to grasp independently (Lipscomb

et al., 2004). Lipscomb also states that student’s

errors are expected, but the teacher should give

feedback and prompting so that the student is able to

achieve the task or goal. The teacher begins the

process of fading and the gradual removal of the

scaffolding when the students take responsibility for

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

154

the task and masters the task, which allows them to

do it independently.

2.3 Scaffolding vs Rescuing

Thompson (2010) differentiates two aspects of

scaffolding, first, when the teacher’s activity is

classified as the real help (scaffolding) or second,

when the teacher’s activity is classified as a sense of

urgency (rescuing). According to Thompson, there

are 13 points that make scaffolding and rescuing are

different. The 13 points are summarized in three

points. Scaffolding concepts consist of; firstly, it

takes in-depth knowledge of readers as well as the

instructional practices that will most benefits them,

and secondly the students are working just as hard as

the teacher (if not harder) as the teacher assumes a

facilitative role-supporting, modelling, and

encouraging, and thirdly scaffolding requires a shared

responsibility with an end goal in mind.

In addition, the criteria of rescuing consist of;

firstly, rescuing definitely had a sense of urgency for

their readers to get it right, secondly the teacher is

generally the only one working-the sole responsibility

is placed on the rescuer, and thirdly rescuers simple

take over.

3 METHODOLOGY

This study was designed as a qualitative method with

a case study approach. Qualitative method is

appropriate to this investigation as it produces

detailed data from a small group of participant (Coll

& Chapman, 2000) while exploring feelings,

impressions, and judgments (Best & Kahn, 2006).

Moreover, qualitative method is suitable to develop

hypothesis for further testing, understanding the

feelings, values and perception that underlie and

influence behavior. Qualitative is a multi-method in

focus, involving an interpretative, naturalistic

approach to its subject matter, which means that the

researcher sees things in different angle or different

point of view (Malik & Hamied, 2016).

The site for this study was conducted in one of the

best junior high school in Lembang, west Bandung

regency. One English teacher and thirty nine students

involved in this study. The choice of informants and

participants was based on their potential to supply the

data needed for this study.

Three data collections were employed in this

study. There were; classroom observation, interview,

and document analysis. The data collection was

conducted from March 24

th

,

2017 to June 15

th

, 2017.

The recording’s results were transcribed, coded,

categorized and analyzed. After that, analysis of each

data collection was synthesized and discussed to

answer the research questions.

4 FINDINGS

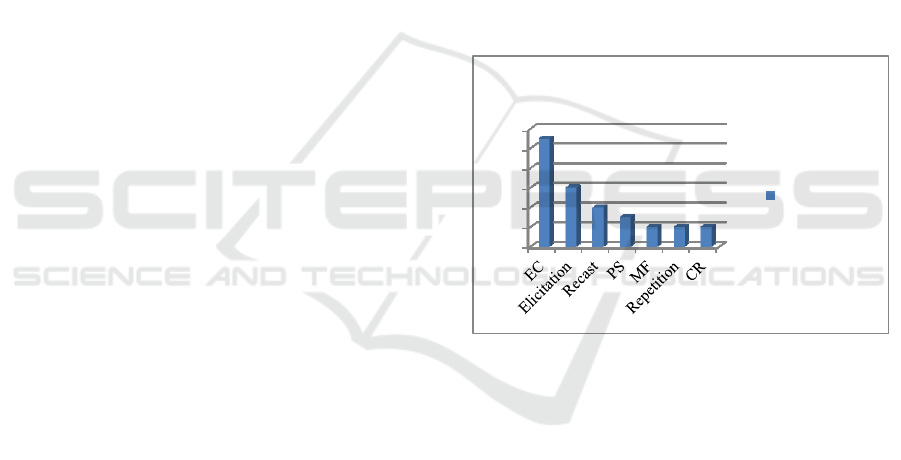

The analysis showed that the teacher used various

types of oral corrective feedback followed by explicit

correction among the other types used during the

speaking practice. This analysis found that there are

seven types of corrective feedback as in the teacher’s

strategy in improving the students’ spoken English

competence. The corrective feedback types consist of

explicit correction, elicitation, recast, linguistic

feedback, paralinguistic signal, repetition, and

clarification request. The distribution of oral

corrective feedback in the classroom is illustrated in

Figure 1.

Figure 1: The distribution of oral corrective feedback types.

4.1 The Teacher’s Focus in Explicit

Correction

In correcting the students’ error, the teacher had main

concern in choosing any types of errors or mistakes

that were made by the students. Based on the

classroom observation, the teacher had frequently

corrected the students’ error on the grammatical

errors and then followed by phonological errors.

By doing the corrective feedback to the students,

they were helped to increase their understanding of

the background knowledge, especially for the use of

tense, specifically between present and past. The

teacher preferred using explicit correction since the

teacher believed that the students needed a further

explanation about the concept of basic grammatical

form. Ran and Danli (2016) claimed that explicit

correction is an effective way for students to correct

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

The Total of Corrective Feedback

The Total of

Corrective

Feedback

Explicit Correction in Scaffolding Students: A Case of Learning Spoken English

155

their mistakes because teachers provide the

correction.

The data also showed that the learners did not

operate the linguistic features correctly. The teacher

used the explicit correction mostly about the students’

error especially on tenses. According to Littlewood

(1980) as cited in Fawbush (2010) this phenomenon

usually happens when the students were asked to

change the tense. This statement was also justified by

the teacher. The teacher assumed that grammatical

form is the most vital type of error that should be

corrected, because of the language’s cultural

differences of the students between Bahasa and

English languages.

4.2 The Characteristics of Explicit

Correction

The teacher believed that explicit correction is an

effective way for the teacher in correcting the

students’ error and mistake. The teacher also argued

that explicit correction can save the time and energy

for the teacher, as a result, the teacher didn’t need an

extra time to only focus on the students’ error

repeatedly.

By using explicit correction, the teacher could

clearly indicate that the students’ utterance contained

an error and then the teacher gave the direct

correction to them. For example, as mentioned in

Excerpt 4.1:

T : bukan was, tapi diganti sama is.

Easy emotion, itukan dipakai pake apa?

Harusnya kalimatnya ini apa? “He gets

angry easily” nah gitu ngomongnya.

Disini jangan lupa harus pakai “s”

((teacher is pointing the word “get”)).

Karena HE, inget. He loved his family,

iyaa liat sini kurang tepat ((Teacher is

circling the word “loved”)). Hello... ha...

kalau sudah koma jangan H nya besar

juga.

Regarding the effectiveness of explicit correction,

this type of corrective feedback brings some

advantages for the learners in the classroom. Since it

is believed that explicit correction can avoid the

students’ ambiguity and reduce confusion, because

the teacher stated what is incorrect and what is

correct.

It is also supported by Emilia (2010) who asserts

that learning occurs more effectively when the

teachers are explicitly talking about what is expected

of students. Moreover, some experts claim that

explicit correction is useful for the students who have

limited knowledge of the target language, such as

beginning and intermediate students (Lyster & Ranta,

1997). As it can be seen on the subheading of the

teacher’s focus in explicit correction, the teacher

claimed that most of the students’ errors were in the

grammatical form. This was because the students

were lack of the English competences and also

because English is not the students’ native language.

On the one hand, explicit correction can also have

some drawbacks for the students. This type of

corrective feedback can be less effective for the

students to modify their faulty utterances as stated by

Lyster and Ranta (1997). The moment when the

teacher directly indicates the students’ error can also

be a problem for the students, because it can disturb

the flow of students’ communication (Long, 1996). In

addition, explicit correction also has the tendency for

the students to feel humiliated because the teacher

gives the correction at the same time when the

students uttered the mistakes (Lowen & Reinders,

2011). It can be seen from the observation that some

of the students lowered their voices or just keeping

their silence while the teacher corrected their

mistakes.

In order to judge whether the teacher’s corrective

feedback is classified into some types of corrective

feedback, the researcher finds that there are

prominent factors that can be interpreted as the

characteristic of explicit correction. The analysis

shows that the teacher used explicit correction in the

following characterization. The first characterization

is notifying the students’ error which means the

teacher explicitly told to the students that they were

making the error. Here are some examples of

students’ error notification of explicit correction:

Excerpt 4.2

T : aaa ini tidak boleh was.. (You may not

use was) ((The teacher is trying to

correct the student’s error on the white

board)).

Excerpt 4.3

Z : what does his look like?

T : Ooh ... salah kamu, what does HE!

(Ooh... you are wrong, what does HE).

From the two excerpts, it shows that the teacher

mentioned the students’ error spontaneously in

natural interaction. There were no some kinds of chit-

chat that were uttered by the teacher to correct the

students’ errors. Without any consideration in

choosing many types of a good manner in

communicating the erroneous, the teacher signalled

the error that was made by the students directly.

The second characterization is providing the

input, which means the teacher gives the correct form

of the students’ error or an accurate answer.

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

156

Additionally, further explanations also provided by

the teacher in order to minimize the students’ error for

the next lesson. For example:

Excerpt 4.4

T : Kalau was itu untuk kata kerja lampau,

misalnya kalau dulu ayahku suka

marah, maka dipakai was. Apakah

sekarang ayahnya masih suka marah?

(“Was” is used to indicate that something

happened in the past, if in the past, your

father was easy to get anger so you can

use “was. Now, does your father still get

anger?”)

S : ((nodded))

T : bukan was, tapi diganti sama is (It is not

‘was” but it must be changed into “is”)

From the excerpts above, it can be concluded that

in explicit correction, the teacher tended to declare the

students’ error unambiguously. The teacher

attempted to mention and communicate the error that

was made by the students, indicated the student’s

error, and jumped to the correct answer.

As it can be seen in the excerpt 4.1, 4.2, and 4.9

the teacher clearly indicated that what the students

said was irrelevant. The word “not” is the

predominated character in this conversation. The

teacher precisely mentioned what kind of error that

the students made in their assignment. It can be

formulated that in explicit correction, the teacher

mostly used the pattern such as “It is not X but Y’,

“You should say X”, “We say X not Y” as stated by

Sheen (2011). It is also supported by Surakka (2007)

and Ellis (2009) who determine two characters of

explicit correction. According to them, explicit

correction contained some executions that were made

by the teacher in terms of the students’ error and the

teacher’s direct correction of the students’ errors.

4.3 The Teacher’s Strategy in Explicit

Correction

In the process of indicating the students’ error in the

classroom, especially in the types of corrective

feedback for explicit correction, it was found that

there were similar patterns that the teacher applied in

correcting the students’ errors. Based on the

classroom observation, there were two strategies that

were used by the teacher, which can be classified into

some types of teacher’s strategy, such as; correcting

by giving motivation and correcting by emphasizing.

4.3.1 Correcting by Giving Motivation

The motivation that the teacher gave to the students

can be interpreted from the teacher’s utterance to the

students’ performance. According to Nyborg (2011)

the term motivational utterances refer to the teacher

utterances that can help to increase pupils' expectancy

of success and task value.

4.3.2 Correcting by Emphasizing

Based on the observation, correcting by emphasizing

as a way of correcting done by the teacher can be

classified into two points.. Firstly, emphasizing in

order to get the students’ attention. Secondly,

emphasizing on the students’ mistakes and errors.

Emphasizing the sentence with the aim to get the

students’ attention is one of the strategies that the

teacher utilized in the classroom in order to indicate

that the students’ error.

4.4 Explicit Correction related to

Scaffolding

This type of corrective feedback is classified as the

scaffolding because:

First, there is the responsibility between the

teacher and students to change the correct answer.

Besides the teacher indicated the students’ mistakes,

he also gave some explanations in terms of the

mistakes. On the other hand, by some explanation that

have been mentioned by the teacher, the students can

clarify the correct answer.

Second, this type is not classified as rescuing

because the teacher provided some input, not just

leave the students’ mistake.

5 CONCLUSION

It can be concluded that this study showed a different

trend of research in the feedback of scaffolding. The

findings are different from those of previous research,

in which recast is the most frequently used types of

corrective feedback by many teachers (see Lyster &

Ranta, 1997; Panova & Lyster, 2002; Sheen, 2004;

Anghari & Amirzadeh, 2011; Maolida, 2013;;

Esmaeili and Behnam, 2014;q; Bhuana, 2014; and

Subekti, 2016).

Firstly, explicit correction is the most dominant

type used by the teacher in the classroom. According

to the teacher, explicit correction is the best way that

the teacher can do to correct the students’

mistakes/errors especially in saving the teacher’s time

Explicit Correction in Scaffolding Students: A Case of Learning Spoken English

157

and energy. The teacher can indicate the students’

error directly, and then give the further explanation

Secondly, explicit correction can avoid students’

ambiguity and reduce confusion because the teacher

stated what is correct and what is incorrect.

Moreover, explicit correction is useful for the

students who have limited knowledge of the target

language, such as beginning and intermediate

students as stated by Lyster and Ranta (1997)

The type of corrective feedback that is used by the

teacher in this study is determined based on the level

and the characteristics of the students in the

classroom. Based on this observation, the type of

explicit correction, which is dominantly used by the

teacher is the appropriate type that is used in this

context, especially for the types and the

characteristics of the students in this classroom

observation. Explicit correction comes in order to

answer the students’ needs. The teacher scaffolds the

students based on some utterances and episodes in

which it is improving their performance and

competence in learning English.

REFERENCES

Ahangari, S., & Amirzadeh , S. 2011. Exploring the

teacher's use of spoken corrective feedback in teaching

Iranian EFL learners at different level of proficiency. In

Z. Bekirogullari (Ed.), Proceedings of the 2nd

International Conference on Education and

Educational Psychology. 29, pp. 1859-1868. Elsevier.

Retrieved from

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S187

7042811029028

Best, J.W. & Kahn, J. 2006. Research in education. New

Delhi: Prentice Hall of India Pvt. Ltd.

Beuningen, V. C. 2010. Corrective feedback in L2 writing:

Theoretical perspectives, empirical insights, and future

directions. International Journal of English Studies,

10(2), 1-27.

Bhuana, G.P. 2014. Oral corrective feedback for students

of different proficiency levels (Master’s Thesis).

Department of English Education, School of

Postgraduate Studies, Indonesia University of

Education, Bandung, Indonesia.

Calsiyao, I. S. 2015. Corrective feedback in classroom oral

errors among Kalinga- Apayao state college students.

International Journal of Social Science and Humanities

Research, 3 (1), 135.

Coll, R. K., & Chapman, R. 2000. Qualitative or

quantitative? Choices of methodology for cooperative

education researchers. Journal of Cooperative

Education., 35(1), 25-35.

Derakhshan, A., Khalili, A.N., & Baheshti, F. (2016).

Developing EFL learner’s speaking ability, accuracy

and fluency. English Language and Literature Studies,

6(2), 177-186.

Ellis, R., Loewen, S., & Erlam, R. 2006. Implicit and

explicit corrective feedback and the acquisition of L2

grammar. Studies in Second Language Acquisition,

28(2), 339-368.

Ellis, R. 2009. Corrective feedback and teacher

development. L2 Journal, 1(1), 3-18.

Emilia, E. (2010). Teaching writing: Developing critical

learners. Bandung: Rizqi Press.

Esmaeili, F., & Behnam, B. 2014. A study of corrective

feedback and learner's uptake in classroom interactions.

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English

Literature, 3(4), 204-212.

Fajriah, Y.N. 2015. Comprehensible input, explicit

teaching, and corrective feedback in genre based

approach to teaching spoken hortatory exposition

(Master’s Thesis), Department of English Education,

School of Postgraduate Studies, Indonesia University of

Education, Bandung, Indonesia.

Fawbush, B. 2010. Implicit and explicit corrective feedback

for middle school esl learners. Hamline University.

Gass, S. M. 1991. Grammar instruction, selective attention,

and learning. In R. Phillipson, E. Kellerman, L.

Selinker, M. Sharwood Smith, & M. Swain (Eds.),

Foreign/second language pedagogy research (pp. 124-

141). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Hammond, J. 2001. Scaffolding: Teaching and learning in

language and literacy education. Newtown, NSW:

PETA.

Hammond, J., Gibbons, P. 2001. What is scaffolding? In J,

Hammond (Ed.), Scaffolding teaching and learning in

language and literacy education (pp. 1-14). Sydney:

Primary English Teaching Association Australia

(PETA).

Harmer, J. 2007a. The practice of English language

teaching. Malaysia: Pearson Education.

Kagimoto, E., & Rodgers, M. P. H. 2008. Students’

perceptions of corrective feedback. In K. Bradford

Watts, T. Muller, & M. Swanson (Eds.), JALT2007

Conference Proceedings. Tokyo: JALT.

Lawson., & Linda. 2002. How Scaffolding works on a

teaching strategy. Retrieved from

http://condor.admin.ccny.cuny.edu/~group4/Lawson/

%20paper-doc

Lengkanawati, N.S. 2017. Learner autonomy in the

Indonesian EFL settings. Indonesia Journal of Applied

Linguistics, 6(2), 222-231.

Li, S. 2010. The effectiveness of corrective feedback in

SLA: A meta-analysis. Language Learning, 60(2),

309–365.

Lipscomb, L., Swanson, J., & West, A. 2004. Scaffolding.

In M. Orey (Ed.),

Emerging perspectives on learning, teaching and

technology. Retrieved from

http://epltt.coe.uga.edu/index.php?title=Scaffolding

Loewen, S., & Reinders, H. 2011. Key concepts in second

language acquisition. Basingstoke: Palgrave

Macmillan.

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

158

Lyster, R., & Ranta, L. 1997. Corrective feedback and

learner uptake: Negotiation on form in communicative

classrooms. Studies in Second Language Acquisition,

19(1), 37-66.

Malik, R.S., & Hamied, F. A 2016. Research methods: A

guide for the first time researchers. Bandung: UPI

Press.

Maolida, E. H. 2013. Oral corrective feedback and learner

uptake in a young learner EFL classroom: A case study

in an English course in Bandung (Master’s Thesis).

Department of English Education, School of

Postgraduate Studies, Indonesia University of

Education, Bandung, Indonesia.

Martinez, S.G. 2006. Should we correct our students’ errors

in l2 learning?. Encuentro 16, 1-7.

Maybin, J., Mercer, N., & Stiere, B. 1992. 'Scaffolding'

learning in the classroom. In H., &. Stoughton (Ed.),

Thinking voice (pp. 21-31). London.

Mendez, E. H., & Cruz, M.D.R. 2012. Teachers’

perceptions about oral corrective feedback and their

practice in EFL classrooms. PROFILE. 14(2), 63-75.

Nyborg, G. 2011. Teachers use of motivational utterances

in special education in Norwegian compulsory

schooling. A contribution aimed at fostering an

inclusive education or pupils with learning difficulties.

International Journal of Special Education, 26(3), 248-

259.

Panova, I., & Lyster, R. 2002. Patterns of corrective

feedback and uptake in an adult ESL classroom. TESOL

QUARTERLY, 36(4), 575-595.

Ran, Q., & Danli, L. 2016. Teachers' feedback on students'

performance in a secondary EFL classroom.

Proceeding of CLaSIC, (pp. 242-254). Singapore.

Rezaei, S., Mozaffari, F., & Hatef, A. 2011. Corrective

feedback in SLA: Classroom practice and future

directions. International Journal of English Linguistics,

1(1), 21-29.

Sheen, Y. 2007. The effects of corrective feedback,

language aptitude, and learner attitudes on the

acquisition of English articles. In A. Mackey (Eds.),

Conversational interaction in second language

acquisition: A collection of empirical studies (pp. 301-

322). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Subekti, E. 2016. Teacher oral corrective feedback in a

non-formal adult EFL conversation class (Master’s

Thesis). Department of English Education, School of

Postgraduate Studies, Indonesia University of

Education, Bandung, Indonesia.

Sheen, Y. 2011. Corrective feedback, individual differences

and second language learning. NewYork: Springer.

Thompson, T. 2010. Are you scaffolding or rescuing?

Retrieved from

http://eldnces.ncdpi.wikispaces.net/file/view/Are+You

+Scaffolding+or+Rescuing.pdf.

Explicit Correction in Scaffolding Students: A Case of Learning Spoken English

159