Examining Conversation of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder

(ASD)

An Application of Grice’s Cooperative Principle

Yana Andira Aprilidya and Ernie D. A. Imperiani

Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia

ernie_imperiani@upi.edu

Keywords: Grice’s Cooperative Principle, Observance of Maxims, Non-Observance of Maxims, Autism Spectrum

Disorder (ASD).

Abstract: This study looks at how individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (henceforth ASD) understand messages

in a conversation. This study is a case study that focuses on two children with ASD in schools for special

needs in Bandung. Applying Grice’s Cooperative Principle, this study examines the observance and non-

observance of maxims as well as the possible reasons underlying the non-observance of maxims by children

with ASD. The data which are in the form of texts are obtained from recorded conversations and are

analyzed qualitatively. Findings reveal that both children mostly observe all four maxims. However, there

are also a small number of instances of non-observance of maxims; namely, flouting, infringing, violating,

and opting out that are committed. The reasons behind the non-observance of maxim are, among others,

impairment in speaking performance and imperfect command of language. The findings indicate that

children with ASD in this context generally manage to create successful communication with their

interlocutors. Nevertheless, there are also very rare cases of breaking maxims in which they sometimes

make attempts to evoke jokes, avoid uncomfortable situations, and generate other meanings. In fact, these

children sometimes fail to produce true and brief utterances due to the characteristics of their language

skills.

1 INTRODUCTION

As a means of social interaction, communication has

its own purposes such as conveying messages and

maintaining relationships. In order to create and

enhance successful communication, Grice (1975)

proposes Cooperative Principles that speakers need

to adhere, which are widely known as four Gricean

maxims. The four maxims require the speakers to

give true, sufficient, relevant, brief, and clear

information or contribution.

However, people do not always observe or pay

attention to the maxims, in which it can be done

secretly, intentionally, or unintentionally due to

several reasons (Rundquist, 1991; Dornerus, 2005;

Mukanin and Izzah, 2006; Patridge, 2006; Mukaro,

Mugari and Dhumukwa, 2013 and Thomas, 2013).

This is what is referred to non-observance of

maxims. Non-observance of maxims is divided into

five types, namely flouting, violating, infringing,

opting out, and suspending (detailed explanations for

each types of non-observance see Thomas, 2013).

This makes the applications of Gricean maxims vary

from time to time, which are interesting to be

investigated. Therefore, this opresent study is

conducted to examine both observance and non-

observance of maxims. More specifically, it attempts

to discover how children with ASD observe and

break the maxims.

Autism Spectrum Disorder is a disorder which

commonly begins in infancy or the first three years

since the individuals are born (Lord, Cook,

Leventhal, and Amaral, 2000). Individuals with

ASD have distinctive characteristics in three skills,

which are in behavior, social or interactional skills,

and language and communication skills (de Villiers,

Stainton, and Szatmari, 2007).

Regarding behavior, individuals with ASD have

unusual attachments to objects (de Villiers et al.,

2007), have stereotyped behaviors such as hand

flapping, twirling, and repetitive finger movements

(Johnson and Myers, 2007), and have a routine like

go through the same order of routines again and

Aprilidya, Y. and Imperiani, E.

Examining Conversation of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) - An Application of Grice’s Cooperative Principle.

DOI: 10.5220/0007168003990405

In Proceedings of the Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference

on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education (CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017) - Literacy, Culture, and Technology in Language Pedagogy and Use, pages 399-405

ISBN: 978-989-758-332-2

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

399

again, thus making it uneasy for them to adapt to

changes which might mix up the order of the

routines (Nordqvist, 2015).

In terms of language and communication skills,

Philofsky and Hepburn (as cited in Wallace, 2011)

state that children with ASD have poor topic

maintenance and lack reciprocity in conversation.

Furthermore, Johnson and Myers (2007) add that

they have echolalia, a condition when they repeat

words or phrases spoken by their interlocutors.

Echolalia may also exist throughout their lifetime.

For social or interactional skills, unlike children

in general, children with ASD often do not seek

other people when they are happy (Lord et al.,

2000). This is in line with de Villiers, Stainton and

Szatmari (2007) who state that children with ASD

lack peer relationship and shared attention. In

addition, those children also lose temper, have

outburst, and even cry every time they are

interrupted during play (de Villiers, Stainton and

Szatmari, 2007). Since individuals with ASD are

generally known as individuals who have difficulties

in several skills, including skills in communication,

it becomes essential for people, especially those who

have close relation with people with ASD, to

understand and learn more about the utterances they

produce in communication.

2 METHODS

This present study is a case study since this study

focuses on two ASD children who study at

elementary schools for special needs in Bandung to

describe and interpret the communication between

the ASD participants and other people regarding the

observance and non-observance of maxims. This is

in line with Hitchcock and Hughes (as cited in

Cohen, Manion, and Morrison, 2000) who state that

a case study focuses on an individual, individuals, a

group, or groups of individuals.

As a qualitative research, audio recording, non-

participant observation, and open-ended interview

are conducted to collect the data. This is in line with

Creswell (2009) who suggests that qualitative

researchers commonly gather multiple forms of data,

such as interviews, observation, and documents,

rather than relying on a single data source. In

addition, non-participant observation was used

because the study aims to gain and observe

occurrences which normally happen; those without

any involvement from the researcher. While for the

interview, open-ended type of interview allows the

researcher to ask the same questions in the same

order in which those questions can lead to different

yet comparable answers (Cohen, Manion and

Morrison, 2000).

Using theory from Grice (1975) and Thomas

(2013), the data were analyzed in five steps of data

analysis, which are, identifying what maxims are

observed and broken by both children with ASD,

categorizing the broken maxims into the types of

non-observance, discovering the possible reasons

underlying the cases of non-observance of maxims,

interpreting the findings by referring and relating to

theories, and drawing conclusions from the whole

findings.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The findings reveal that all maxims are both

respected and not observed. Yet, occurrences of

observance of maxims and occurrences of non-

observance of maxims have different numbers. Of

the two cases, the former has significantly larger

number than the latter. In other words, occurrences

of observance of maxims are more dominant.

Furthermore, the findings also show that there are

four out of five types of non-observance of maxims

committed. They are flouting, infringing, violating,

and opting out. In addition, the possible reasons

behind the non-observance of maxims include

reasons such as impaired speaking performance,

imperfect command of language in young children,

echolalia, and several other reasons which include

personal reasons. The following section discusses

findings in detail regarding observance of maxims,

followed by non-observance of the maxims and its

possible reasons.

3.1 Observance of the Maxims

With regard to observance of maxims, all four

maxims are evidenced in this study with a large

number of occurrences. This finding indicates that

most of the time, both children with ASD adhere to

Grice’s Cooperative Principle, suggesting that they

mostly create successful communication. However,

if a comparison is made between the two children

(Anggi and Fahri), Fahri performs more observance

of maxims than Anggi, suggesting that he observes

all four maxims more frequently than Anggi. The

number of each observed maxim by Anggi and Fahri

is presented in the next table.

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

400

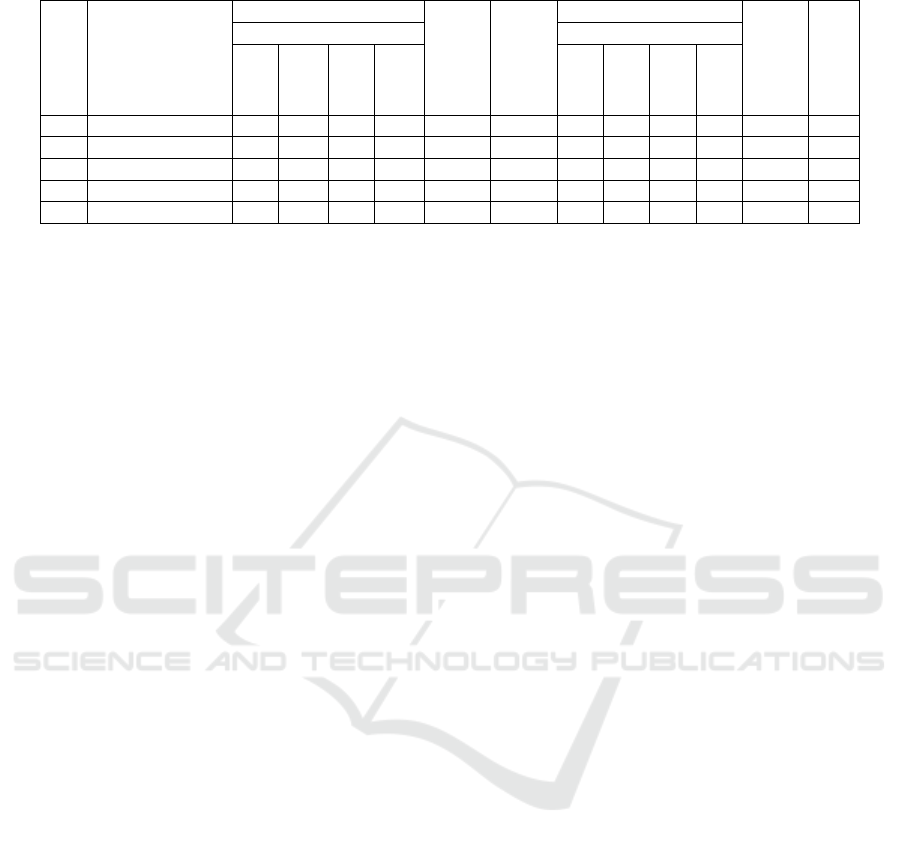

Table 1: The distribution of observed maxims by Anggi

and Fahri.

No

Observed

Maxims

Anggi Fahri

Frequency Percentage Rank Frequency Percentage Rank

1 Maxim of quality 67 24,8% 2

106 25,7% 2

2 Maxim of quantity 60 22,2% 4

96 23,2% 4

3 Maxim of relation 82 30,4% 1

108 26,1% 1

4 Maxim of manner 61 22,6% 3

103 25,0% 3

Total 270 100%

413 100%

From the table 1, it can be seen that maxim of

relation has the highest numbers of observance,

either by Anggi or by Fahri, followed by maxim of

quality, maxim of manner and maxim of quantity.

Due to the limited space of this paper, only

examples from the most and the second most

frequently observed maxims are provided in this

paper. Complete examples on each maxim

observance from both children are not provided here

but can be seen in Aprilidya (2016).

As revealed in Table 1, maxim relation has the

highest numbers of observance, either by Anggi or

by Fahri. This indicates that most of the time, Anggi

and Fahri give relevant contributions, which is in

line with Grice (1975) who states that the only way

to observe maxim of relation is by providing

relevant information or contribution. However, this

also suggests that they stick to the ongoing topics

almost all the time and they hardly ever break this

maxim in order to generate implicature as people

commonly do. An example of observance of maxim

of relation by Anggi is provided in the following

example:

[a1] T : ke mana Bu Ipehnya?

Where is she?

Anggi : ke rumah sakit ibunya

She is in a hospital

In example [a1], Anggi manages to give a

relevant answer to her teacher’s question. In that

example, she is aware that the question “where”

must be responded by mentioning a place.

Meanwhile, an occurrence of observance of this

maxim by Fahri is presented in the following

example.

[a2] T : paling juga istirahat ya, bentar lagi

istirahat da ini

Just wait until recess, it is almost recess okay

Fahri : Ibu::: po ih po ih (pop mie pop mie)

Ma:::m, pop mie pop mie

T : iya nanti tiitp dibeliin sama Wulan ya:::h

Right we will ask Wulan to buy it oka:::y

The example is one of the textual evidence that

Fahri respects maxim of relation. When his teacher

(T) mentions about recess, he is aware that he gets to

have meals, thus, he produces the utterance saying

what food he wants to have.

The second most frequently observed maxim is

maxim of quality which is fulfilled by Anggi and

Fahri for 67 and 106 times, respectively. This

suggests that Fahri respects this maxim more

frequently than Anggi. Despite those numbers, it is

evidenced that maxim of quality is mostly observed

by both Anggi and Fahri by giving true information

and being truthful. An occurrence of observed

maxim of quality by Anggi is presented as follows:

[b1] T : pagi::: Anggi udah makan belum?

Good morni:::ng Anggi, have you had breakfast?

Anggi : udah, sosis.

I have, I had sausage.

In example [b1], it is seen that Anggi provides

information which does not lack evidence.

According to the situational context, Anggi has

indeed had breakfast before she goes to school, thus,

the utterance “udah, sosis” observes maxim of

quality even though it breaks maxim of quantity.

Meanwhile, an occurrence of Fahri observing

maxim of quality is presented in the following

example:

[b2] T : Fahri ke sini naik apa?

How did you get here?

Fahri : na::: ih moto (naik motor)

I came here by motorcycle

In example [b2], it is also evidenced that Fahri

observes maxim of quality by giving true

information. By referring to the situational context,

he always goes to school by motorcycle with his

father.

3.2 Non-Observance of the Maxims

and Its Possible Reasons

Despite the large number of observance of maxims,

there are still a small number of non-observance of

maxims. Anggi and Fahri occasionally break the

maxims which are due to an attempt to create

another meaning, intention to tell a lie, and

incapability to speak clearly. Table 2 below presents

number of occurrences of broken maxims along with

the type of non-observance committed is presented.

Examining Conversation of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) - An Application of Grice’s Cooperative Principle

401

Table 2: The distribution of types of non-observance of maxims by Anggi and Fahri.

No

Types of non-

observance of

maxims

Anggi

Total

Ran

k

Fahri

Total

Ran

k

Types of maxims Types of maxims

Qualit

y

Quantit

y

Relation

Manne

r

Qualit

y

Quantit

y

Relation

Manne

r

1 Floutin

g

6 18 4 11 39 2 - 10 1 3 14 1

2 Infringing 12 10 3 16 41 1 2 3 - 3 8 2

3 Violatin

g

5 - - - 5 3 1 - - - 1 4

4 O

p

tin

g

Out - 1 - 1 2 4 - 3 - 3 6 3

Total 23 29 7 28 87 3 16 1 9 29

From table 2, types of non-observance of

maxims which are committed are flouting,

infringing, violating, and opting out. Suspending,

another type of maxim non-observance, is not

evidenced in this study. Regarding flouting (a case

which occurs when a maxim is intentionally broken

because the speaker attempts to create an implicit

meaning), Anggi flouts more frequently than Fahri

which also means that she has more intention to

deliberately break the maxims. An example of

flouting by Anggi is presented as follows:

[c1] T : dua::: mata?

Who’s got two eyes?

Anggi : saya:::

me:::

T : hidung saya?

my nose is?

Anggi : pese:::k ((smiles))

fla:::t ((smiles))

T : ((laughs))

((laughs))

In example [c1], it is obvious that Anggi does not

sing the right lyrics and thus flouts maxim of

quality. She says what she believes to be untrue and

attempts to crack a joke. This case is in accordance

with Dornerus (2005) who states that maxims can be

flouted for various reasons such as evoking humor.

As for Fahri, an example of flouting by Fahri is

presented as follows:

[c2] T : jam sepu:::lu:::h.Fahri udah makan?

It is ten o’clock. Have you eaten

something?

Fahri : u ah. Po ih, the ge ah (udah. Pop

mie, teh gelas)

Yes I have. I had pop mie and teh

gelas

In example [c2], by conveying more information

than required, he flouts maxim of quantity. This is in

line with Wallace (2011) who states that it is not

necessary to provide extra information to the one

who poses the question. The question is a yes or no

question, yet he answers not only with a yes but also

with additional information. In this example, it is

obvious that he wants his interlocutors to know what

food he has had

For infringing (a case when a maxim is

unintentionally broken by the speaker), Anggi

infringes all maxims for 41 times while Fahri

infringes three maxims (all maxims except maxim of

relation) for only 8 times. An example of infringing

by Anggi is presented in the following example:

[d1] R : di sekolah ada pelajaran olahraga

nggak?

your school have sport class, doesn’t

it?

Anggi : pelajaran olahraga nggak? Ada

Sport class, doesn’t it? Yes, it has

In the conversation, Anggi’s utterance infringes

maxim of manner because it contains unnecessary

words “pelajaran olahraga nggak?” Furthermore, the

reason for this infringement is a characteristic of

individuals with ASD called echolalia, a state of

repeating the last words or phrases uttered by one’s

interlocutors. As for Fahri, infringing occurs as

provided in the following example:

[d2] Fahri : Oma:::n (.) Oma:::n

Oma:::n (.) Oma:::n

F : apa?

what?

Fahri : hah hah

hah hah

F : kenapa?

what happened?

Fahri : hah hah ((flutters his hand around

his mouth))

hah hah ((flutters his hand around his

mouth))

Example [d2] is a conversation between Fahri

and his friend, more specifically when Fahri is

having a meal; a spicy one. By saying “hah hah”,

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

402

maxim of manner is infringed because the utterance

“hah hah” alone is rather unclear and obscure for the

interlocutor. This clearly breaks the rules of maxim

of manner proposed by Grice (1975) which is to be

clear and to avoid obscurity. It is evidenced to be

obscure because Fahri’s friend as the interlocutor did

not understand what Fahri meant and he had to ask

Fahri afterwards. Furthermore, the reason underlying

this case of infringement is impairment in the

speaker’s speaking performance, as mentioned by

Thomas (2013). More specifically, his speaking

performance at that very moment is impaired due to

the sudden feeling he gets from the spicy food he is

eating. The spiciness is what makes it hard for him

to speak clearly.

Regarding violating, it refers to a case when a

speaker secretly breaks a maxim and wishes their

interlocutors to understand something which the

truth is not (Thomas, 2013). The findings show that

there are only a small number of occurrences where

Anggi and Fahri commit violating, and the only

maxim they violate is maxim of quality. Table 2.

shows that Anggi violates this maxim for five times

while Fahri violates this maxim for only one time.

This shows that they hardly ever tell lies, deceive, or

wish their interlocutors to know something except

the truth. An example of violating by Anggi is

presented in the following example:

[e1] T : Anggi tadi belajar apa? Kelas

pertama

Anggi, what did you learn in the

previous class?

Anggi : nggak tau

I don’t know

Example [g1] is a conversation between Anggi

and her teacher before starting the second class. In

the example, her teacher asks Anggi what Anggi has

learned in the first class. However, using the

utterance “nggak tau”, she tells a lie and thus,

violates maxim of quality. This is in line with

Mukanin and Izzah (2006) who states that maxim

can be broken for reasons such as hiding something.

As a matter of fact, she knows what she has learned

in the first class (as what she tells her teacher a few

minutes afterwards). Furthermore, using the

utterance “nggak tau”, she is likely to suggest that

she does not feel like talking about the ongoing topic

at that moment. An example of violating by Fahri is

presented in the following example:

[e2] T : rasanya a:::sem.Fahri kemarin

masuk sekolah nggak?

It is sou:::r. Did you come to school

yesterday?

Fahri : ma uk (masuk)

Yes I did

In the conversation, it is not quite obvious that

Fahri violates a maxim, particularly maxim of

quality. By saying “masuk” when his teacher asks

him whether he attended the class “yesterday”, it is

as if Fahri follow the maxim. But, in fact, he violates

maxim of quality because what he says is not true.

That day was a day off due to the teachers’ training

program outside the school. So, Fahri did not come

to school that day and neither did all of his friends.

This maxim violation is most likely due to one of the

characteristics of individuals with ASD; that is,

“having continuous routine.” More specifically, the

routine in this case is “going to school every day.”

As stated by Nordqvist (2015), having

continuous routine is a great deal in the individuals’

lives, thus, it is not easy for them to adapt to changes

that might appear in the order of the routines. What

Fahri remembers is that he always goes to school.

He does not quite remember the day he does not go

to school, which is why he provides the utterance

“masuk” in that conversation.

For opting out, Anggi opts out from observing

maxims for only two times while Fahri opts out for

six times. In addition, it is necessary to highlight that

in cases of opting out, both Anggi and Fahri opt out

by being silent and not saying anything. An example

of opting out by Anggi is provided in the following

example:

[f1] T : Anggi cantik nggak?

Anggi, are you pretty?

Anggi : cantik nggak?

(are) you pretty?

T : cantik nggak, jawab, ca:::nti:::k,

ca:::nti:::k

Pretty or not, you answer with (I am)

pretty:::, pretty:::

Anggi : ((silent))

((silent))

In the example, it is obvious that Anggi chooses

to be silent when her teacher asks her the question.

The reason for this case of opting out is more of a

personal reason, which is because she is not

interested in the question and thus, she decides to

refuse answering the question. While in Fahri’s case,

violating occurs as presented in the example as

follows:

[f2] T : jam berapa sekarang?

what time is it now?

Fahri : ((silent and then looks away))

((silent and then looks away))

Examining Conversation of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) - An Application of Grice’s Cooperative Principle

403

In example [f2], it is also evidenced that Fahri

opts out from the conversation. Additional

information delivered by his teacher tells that Fahri

has not yet comprehended the concept of time and

currency. This is likely to be the reason which

causes him to refuse to answer the question and be

silent instead. Furthermore, it is plausible to state

that he chooses to keep silent because he does not

want to give a false answer. This is in accordance

with Thomas (2013, p. 74) who states that in opting

out, “the speaker wishes to avoid generating a false

implicature”. Due to the insufficient knowledge of

time, if he did answer the question, he might have

provided a false answer of the current time. Thus, he

decides to be silent.

From the whole findings of this case study, it is

apparent that cases of non-observance of maxims

influenced by characteristics of children with

Autism Spectrum Disorder are cases of infringing

and violating (in this case, violating by the second

participant only). Subsequently, cases of flouting

and opting out are due to their own personal

intentions of generating implicatures, avoiding

uncomfortable situations, cracking joke, hiding the

truth, and refusing to create false answers, as what

people in general commonly do. As a matter of fact,

this is all due to the causes or reasons of flouting and

opting out itself. Unlike infringing, flouting and

opting out are not influenced by impaired speaking

performance, imperfect command of the language,

or any distinctive characteristic of one’s language

skills. Cases of infringing occur unintentionally;

otherwise, cases of flouting and opting out occur

intentionally with the speakers’ deliberate intention.

Furthermore, from the occurrences of flouting,

opting out, and violating (violating by the first

participant), it is evidenced that children with ASD

in this research can respond to certain topics like

people in general usually do. On the other hand,

possible reasons behind infringing and violating

(violating by the second participant) such as

echolalia, unusual attachments to objects,

stereotypies in thought, and habit of having

continuous routine, can be further examined and also

treated to contribute to linguistic therapy for future

directions.

4 CONCLUSIONS

From the findings, it can be concluded that children

with ASD generally manage to create successful

communication, which is indicated by the large

number of occurrences of observance of Gricean

maxims. However, there are also a small number of

non-observance of maxims. The non-observance of

maxims occurs when the two ASD children attempt

to crack jokes, avoid uncomfortable circumstances,

and generate another meaning including cases when

they produce utterances which are not quite brief

and unclear; thus, make their interlocutors confused.

Furthermore, Anggi and Fahri lack conversational

reciprocity. This means that conversations which

occur between Anggi and Fahri and their

interlocutors are started and kept going by the

interlocutors; they hardly ever start the conversation

first. This finding is in line with Philofsky and

Hepburn (as cited in Wallace, 2011) who state that

children with ASD find it hard to initiate

conversation or interaction with people. This is also

in agreement with Lord et al., 2000; de Villiers et al,

2007; and Wallace, 2011 who add that reciprocity in

conversation by children with ASD is lacking.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper was based on the first author’s

undergraduate research paper who was supervised

by Dadang Sudana, M.A., Ph.D. and Ernie D. A.

Imperiani, M.Ed. Our highest appreciation also goes

to those who have helped the whole process of

writing and publishing this article.

REFERENCES

Aprilidya, Y. A., 2016. Grice’s Cooperative Principle In

Conversation Of Children With Autism Spectrum

Disorder (Asd):A Case Study. Unpublished

Undergraduate Research Paper. Indonesia University

of Education, Indonesia

Creswell, J. W., 2009. Research Design: Qualitative,

Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, Sage

Publications. California, 3rd ed.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., Morrison, K., 2000. Research

methods in education, Routledge Falmer. London.

de Villiers, J., Stainton, R. J., Szatmari, P., 2007.

Pragmatic abilities in autism spectrum disorder: a case

study in philosophy and the empirical. Midwest

Studies in Philosophy, 31, pp. 292-317

Dornerus, E., 2005. Breaking maxims in conversation: A

comparative study of how scriptwriters break maxims

in Desperate Housewives and That 70's show.

(Unpublished thesis), Karlstad University, Sweden.

Grice, H. P., 1975. Logic and conversation. In Cole, P.

and Morgan, J. (eds.) Syntax and Semantics 3: Speech

Acts (pp.41–58). New York: Academic Press;

reprinted in Grice, H. P. 1989b, 22–40.

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

404

Johnson, C. P., Myers, S. M., 2007. Identification and

evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders.

American Academy of Pediatrics, 120(5), 1183-1215.

Lord, C., Cook, E. H., Leventhal, B. L., Amaral, D. G.,

2000. Autism Spectrum Disorders. Neuron, 28, 355-

363

Mukanin, S., Izzah, I., 2006. Prinsip kerja sama dan

pelanggarannya dalam bahasa anak usia 7,6 tahun.

Lingua Jurnal Bahasa dan Sastra, 8, 30-40.

Mukaro, L., Mugari, V., Dhumukwa, A., 2013. Violation

of conversational maxims in Shona. Journal of

Comparative Literature and Culture, 2(4), 161-168.

Nordqvist, C., 2015. What is autism? What causes autism?

Retrieved August 19, 2015, from Medical News

Today:

http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/info/autism/

Paltridge, B., 2006. Discourse analysis an introduction,

Continuum. London.

Rundquist, S., 1991. Flouting Grice’s maxims: A study of

gender differentiated speech. Unpublished Thesis.

University of Minnesota, United States.

Thomas, J., 2013. Meaning in interaction: An introduction

to pragmatics, Routledge. New York, 2nd ed.

Wallace, C., 2011. Pragmatic language development in

young children with ASD Honors Research Thesis.

The Ohio State University, United States

Examining Conversation of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) - An Application of Grice’s Cooperative Principle

405