Address Terms in Japanese, Indonesian and Sundanese

As Politeness Strategy in Apology Speech Act

Nuria Haristiani and Renariah Renariah

Japanese Language Education Department,Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia,

Jl. Dr. Setiabudhi No. 229, Bandung, Indonesia

nuriaharist@upi.edu

Keywords: Address Term, Term of Self, Politeness Strategy, Apology, Speech Act.

Abstract: The purpose of this study is to compare the use of address terms in intercultural context, which are in

Japanese, Indonesian and Sundanese, and to analyse the tendency of their function as politeness strategy.

The data in this study were collected by Discourse Completion Test, which investigated eight apology

scenes focused on human relations and situation differences. The participants in this study were 60 Japanese

Native Speakers (JNS), 58 Indonesian Native Speakers (INS), and 54 Sundanese Native Speakers (SNS).

Address terms collected from the data then categorized into “Terms of self” and “Address terms”. The

results suggested that the INS and SNS used “Terms of self” and “Address terms” in various numbers and

expressions to show their consideration to the addressee, while on the contrary, JNS avoid or use less

“Terms of self” and “Address terms” to express their consideration to the addressee. It is clear that as a

politeness strategy, Japanese native speakers tend to minimalize the use of address terms as an attempt to

maintain addressee’s negative face as negative politeness strategy, while Indonesian and Sundanese native

speakers used address terms as positive politeness strategy to maintain their addressee’s positive face.

1 INTRODUCTION

Address terms are words or linguistic expression that

speakers use to appeal directly to their addressees. In

English, for instance, Sir is used in addressing only,

but other words such as you, Helen, daddy, darling,

or Professor Brown have other functions as well as

they are used to talk about other persons rather than

to talk to them directly, and you can be used

generically (Jucker and Taatvitsainen, 2003). The

forms of address terms of address are including

pronouns, nouns, verb forms and other affixes

(Braun, 1988). Suzuki (1973) examined the rules for

using address terms in Japanese by dividing address

terms into two classifications: 1) Jishoushi (term of

self), and 2) Tashoushi (address term). There are

many studies about address terms in Japanese from

many perspectives. Lee (1991) studied about how

address of terms and term of self in Japanese are

used in Japanese and examined about how those use

is omitted in speeches. Other than this study, the use

of address terms in text books (Ohama, 2001). In

other languages, the function of address terms in

sociolinguistics context involves gender difference

also has been examined (Kim, 2015; Afful, 2010;

Rendell-Short, 2009).

Furthermore, in speech act studies, there has

been stated that address terms used in many

languages with their own characteristics. Especially

in apology speech act, Japanese native speakers tend

to use much less address terms compared to Chinese

native speakers (Kusumoto, 2010), English native

speakers (Boyckman and Usami, 2005), and Korean

native speakers (Jung, 2011). Similar to this

tendency, Japanese native speakers also tend to use

less address terms compared to Indonesian native

speakers in apology situations (Takadono, 2000;

Haristiani, 2012). These mean that the use of address

terms in speech acts has different functions and

meaning according to its language and culture

background. In spite of these tendency, there is still

no further inquiry about why Japanese prefer to use

less address terms in apology situation (or other

situations in general), and why in some language

such as Indonesian use so many address terms in

apology situation (or in other situations in general).

To fill this gap, this study aimed to analyse the

use of address terms in apology situations in

different languages and culture background, which

Haristiani, N. and Renariah, R.

Address Terms in Japanese, Indonesian and Sundanese - As Politeness Strategy in Apology Speech Act.

DOI: 10.5220/0007168504230428

In Proceedings of the Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference

on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education (CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017) - Literacy, Culture, and Technology in Language Pedagogy and Use, pages 423-428

ISBN: 978-989-758-332-2

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

423

are in Japanese, Indonesian and Sundanese. The

address terms data collected in this study then

analysed based on Brown and Levinson’s (1987)

politeness theory to determine their function as

politeness strategy.

2 RESEARCH METHOD

2.1 Data Collection and Participants

The data in this study collected through an open

questionnaire which is a “Discourse Completion

Test” (DCT). The DCT was originally conducted as

an inquiry about apology speech act, and the address

terms data used in this study is a part from overall

data collected. The data was collected in Hiroshima

University-Japan, and Universitas Pendidikan

Indonesia-Indonesia. Respondents for this study

were 60 Japanese Native Speakers (JNS), 58

Indonesian Native Speakers (INS), and 54

Sundanese Native Speakers (SNS). All research

objects were undergraduate and graduate students

with average age of 23 years old for JNS, 22.5 years

old for INS, and 22 years old for SNS.

2.2 Discourse Completion Test (DCT)

The DCT used in this study includes 2 apology

situations which are, 1) Apology Situation (“Forgot

to return borrowed book”), and 2) Misunderstood

Situation (“Asked to return the book before promised

due”).

Pronominal forms of address often distinguish

between a familiar or intimate pronoun, and a distant

or polite pronoun on the other (Jucker and

Taatvitsainen, 2003). Hence, to find out about the

difference between address terms used in intimate

and non-intimate relations, besides two different

situations mentioned above, this study also observes

the social distance between the speaker (addresser)

with the hearer (addressee) and set as described as

follows:

1) Status un-equals, intimates: Intimate Lecturer

(IL)

2) Status un-equals, non-intimates: Non-intimate

Lecturer (NL)

3) Status equals, intimates: Intimate Friend (IF)

4) Status equals, non-intimates: Non-intimate

Friend (NF)

Abbreviations above will be used along analysis

in results and discussion to simplify and shorten

explanations.

2.3 Data Analysis

Address terms collected from DCT data then

classified into ‘Term of self’ (Jishoushi) and

‘Address terms’ (Tashoushi). “Term of self”

(Jishoushi) is a pronominal term that the speaker

(addresser) used to mentions himself/herself, and the

so called first-person is only small part of it. In the

other hand, ‘Address terms’ (Tashoushi) is a generic

term of words to refer to the hearer (addressee)

(Suzuki, 1973). The data classified into ‘Term of

self’ and ‘Address terms’ then analysed

quantitatively and qualitatively. Quantitative

analysis conducted by calculating the frequency of

address terms usage overall, and then calculating the

frequency of ‘Term of self’ and ‘Address terms’ in

‘Apology’ and ‘Misunderstood’ situations

specifically. In the other hand, qualitative analysis

conducted based on Brown and Levinson’s

Politeness Theory to identify the function of address

terms in Japanese, Indonesian and Sundanese as

politeness strategy.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 The Overall Use of Address Terms

Address terms used in all apology situations in

Japanese, Indonesian and Sundanese is as shown on

Table 1. Table 1 shows that in both ‘Apology’ and

‘Misunderstood’ situations, INS used the most of

address terms overall, followed by SNS, and lastly

JNS used the least number of address terms.

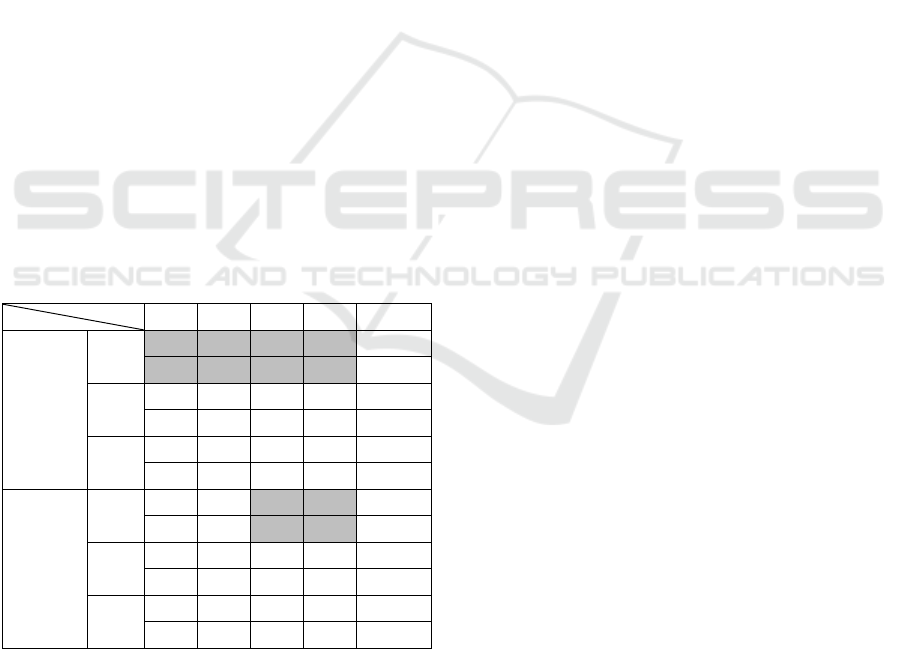

Table 1: Overall address terms using in Apology

Situations and Misunderstood Situations by JNS, INS and

SNS

IL NL IF NF Total

JNS

AS 11 6 0 0 17

MS 12 10 0 5 27

INS

AS 202 227 85 94 608

MS 153 166 58 67 444

SNS

AS 134 126 40 36 336

MS 110 109 31 26 276

Table 1 also shows that the situations difference

affected the amount of use of address terms in

Indonesian and Sundanese, but not in Japanese. In

‘Apology situation’, INS used address terms 608

times while in ‘Misunderstood situation’ they used

those 444 times. This tendency also seen on

Sundanese, when SNS used address terms 336 times

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

424

in ‘Apology Situation’, and 276 times in

‘Misunderstood Situations’.

From above data, we can see that the necessity to

use address terms is higher on ‘Apology Situation’

when the addresser has heavier responsibility to

mend the unbalance relationship between the

addresser and addressee which caused by

addresser’s fault, than in ‘Misunderstood Situation’

where conversely the mistake is on addressee’s side.

However, this tendency was not seen in Japanese,

where JNS slightly used more address terms in

‘Misunderstood Situations’, than in ‘Apology

Situation’. Still, this tendency could mean that in

Japanese, the role of address terms usage in both

situation is not as crucial as in Indonesian and in

Sundanese, and this showed by the number of

address terms used by JNS relatively. Table 1 also

shows that from social distance factor, three

language’s native speakers used address terms in

larger number when the addressee is non-equal

(IL/NL) than equal (IF/NF). Especially in

Indonesian, it is clear that the use of address terms

also influenced by intimacy/familiarity with the

addressee.

3.2 The Use of ‘Term of Self’ and

‘Address Term’ in Apology

Situations

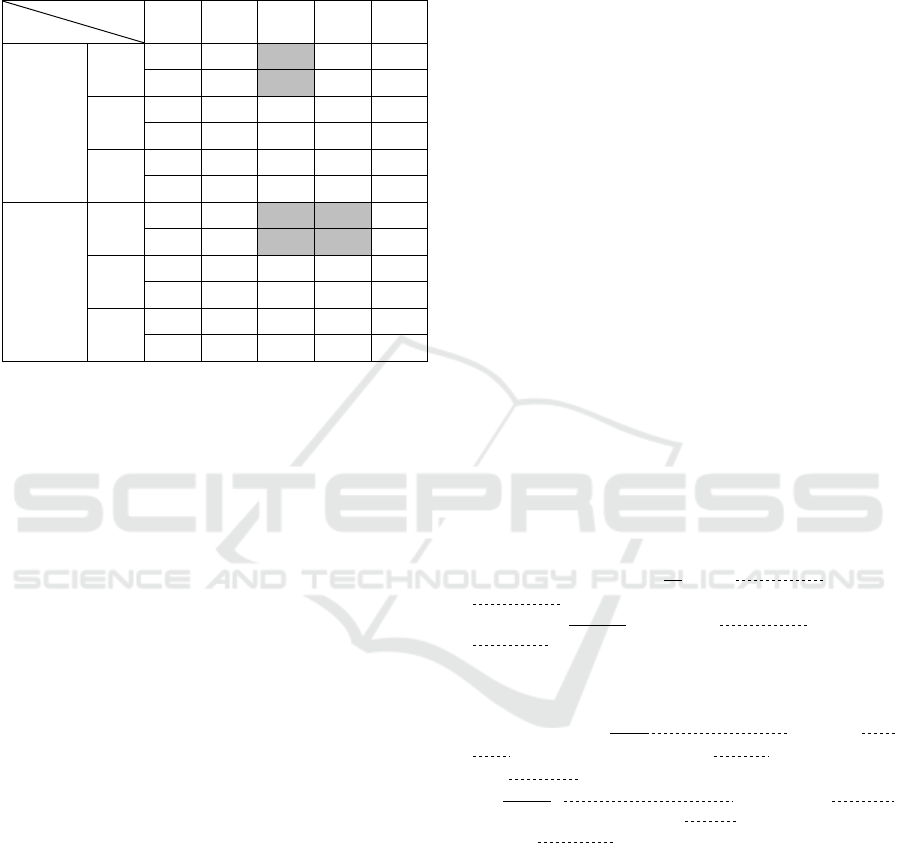

Table 2: ‘Term of self’ and ‘Address Term’ used in

Apology Situations by JNS, INS and SNS.

IL NL IF NF Total

Term of

Self

JNS

0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0 0

INS

123 140 61 69 393

2.12 2.41 1.05 1.17 1.69

SNS

53 54 26 20 153

0.98 1.00 0.48 0.37 0.71

Addres

s Term

JNS

11 6 0 0 17

0.18 0.1 0 0 0.14

INS

79 87 24 25 215

1.36 1.50 0.41 0.43 0.93

SNS

81 72 14 16 183

1.50 1.33 0.26 0.30 0.85

Note: The first row on JNS, INS and SNS represents the number

of address terms used, while the second row represents the

average usage including repetition of address terms in one

utterance.

The specific use of ‘Term of self’ and ‘Address

term’ including its use based on social distance

between the speaker and the hearer is as seen on

table 2. Table 2 shows that based on the type of

address terms used, the three languages show

different tendencies. JNS did not use ‘term of self’ at

all, and only used ‘address terms’. Meanwhile, INS

and SNS used both ‘term of self’ and ‘address

terms’, with larger number on ‘address terms’. INS

used much larger number of ‘term of self’ (393

times), than SNS (153 times). Moreover, INS also

used more ‘address terms’ (215 times) than SNS

(183 times), and lastly followed by JNS (17 times).

From the data above, it can be understood that

compared to the other two languages, Indonesian

prioritized the use of ‘term of self’, where SNS and

JNS prioritized the use of ‘address term’, although in

Japanese the number of its use was not significant.

Table 2 also shows that based on the addressee, JNS

only used ‘address terms’ when the addressee is

non-equal (IL/NL). INS also showed similar

tendency and used both ‘term of self’ and ‘address

term’ more frequently when the addressee is non-

equal and used them in the following sequence:

NL>IL>NF>IF. Meanwhile, SNS tend to use ‘term

of self’ and ‘address term’ differently. SNS used

‘Term of self’ in following order: NL>IL>IF>NF,

while using ‘address term’ in following sequence:

IL>NL>NF>IF, without striking difference in

number.

From above data, it can be examined that in

Japanese and Sundanese language, power distance

(jougekankei) mainly affected the use of address

terms. While in Indonesian, the use of address terms

influenced by both power distance (jougekankei)

with stronger influence, and by intimacy/familiarity

(shinsokankei).

3.3 The Use of ‘Term of Self’ and

‘Address Terms’ in Misunderstood

Situations

After analysing the use of address terms in apology

situation, to examine further about address terms

usage in different situations, the use of address terms

in ‘Misunderstood situations’ will have discussed in

this section. The use of ‘term of self’ and ‘address

term’ by JNS, INS, and SNS in ‘Misunderstood

situation’ is as shown in table 3.

From table 3, it can be seen that the use of ‘term

of self’ and ‘address terms’ in three languages shows

different tendencies. JNS prefer to use both ‘term of

self’ (14 times) and ‘address terms’ (13 times) in

almost the same number, while INS used larger

number of ‘term of self’ (246 times) than ‘address

terms’ (198 times) with significant difference. On

the contrary, SNS used more than twice numbers of

Address Terms in Japanese, Indonesian and Sundanese - As Politeness Strategy in Apology Speech Act

425

‘address term’ (189 times) than ‘term of self’ (87

times).

Table 3: ‘Term of self’ and ‘Address Term’ used in

Misunderstood Situations by JNS, INS and SNS

IL NL IF NF

Tot

al

Term of

Self

JNS

4 5 0 5 14

0.07 0.08 0 0.08 0.08

INS

69 86 38 53 246

1.19 1.48 0.66 0.91 1.06

SNS

25 29 17 16 87

0.46 0.54 0.32 0.30 0.40

Address

Term

JNS

8 5 0 0 13

0.13 0.08 0 0 0.11

INS

84 80 20 14 198

1.45 1.38 0.35 0.24 0.85

SNS

85 80 14 10 189

1.57 1.48 0.26 0.19 0.88

Note: The first row on JNS, INS and SNS represents the number

of address terms used, while the second row represents the

average usage including repetition of address terms in one

utterance.

Table 3 also shows that JNS did not distinguish

the use of ‘term of self’ based on social distance and

used ‘term of self’ similarly to IL, NL and NF.

However, to IF, JNS did not use ‘term of self’ nor

‘address terms’ at all. This tendency could be seen

as evidence that equal-intimate relation in Japanese

language holds special or unique language rules,

which is often different from other social

distance/relations (Abe, 2006; Haristiani, 2010).

Furthermore, JNS used ‘address terms’ only to non-

equal addressee (NL/IL), and none to equal

addressee (NF/IF). Meanwhile, INS showed slightly

different tendency in using address terms in both

‘Apology’ and ‘Misunderstood’ situations. INS used

more ‘term of self’ and ‘address terms’ to non-equal

addressee than to equal addressee. However, the

sequence in using ‘term of self’ is NL>IL>NF>IF,

while in using ‘address terms’ the sequence changed

to IL> NL>NF>IF, with only slight different number

between IL and NL. Similar to INS, SNS used both

‘term of self’ and ‘address terms’ more to non-equal

addressee than to equal addressee, but without

significant difference in number. Even so, SNS used

‘address terms’ to non-equal (IL/NL) and to equal

(IF/NF) with significant difference in number.

From above data, it can be concluded that in all

three languages, power distance (jougekankei)

mainly affected the use of both ‘term of self’ and

‘address terms’. Even more, in Indonesian language,

the use of address terms was clearly influenced also

by intimacy/familiarity (shinsokankei). It is also

examined that situation difference also influenced

the use of ‘term of self’ and ‘address terms’, and

their frequencies.

To examine deeper about the use of address

terms and its function as politeness strategy, in the

next sections ‘term of self’ and ‘address terms’ will

be analyzed by its form and their function as

politeness strategy.

3.4 The Form of ‘Term of Self’ and

‘Address Terms’ and Their

Function as Politeness Strategy

The form of ‘term of self’ and ‘address terms’ used

in Japanese were very simple. Form of ‘term of self’

used in Japanese was only「私 (watashi)」which

means “I” as formal form. This term used only 14

times when the addressee was non-equal (IL/NL)

and non-intimate equal (NF). Since social distance

with the addressees are rather distant, the ‘term of

self’ that used by the addresser was only Watashi.

Moreover, JNS only used one type of ‘Address term’

which is 「先生 (Sensei)」 (30 times), meaning

“Lecturer” or “Teacher”. The use of Watashi and

Sensei are as Example (1) and (2).

Example (1)

(JNS16) 「すみません,私は明日お返しするつもりで

おりました。」

Sumimasen, watashi wa ashita okaeshisuru tsumori de

orimashita.

I’m sorry, I have planned to return it tomorrow.

Example (2)

(JNS51) 「あっ!先生申し訳ありません!忘れていま

した。昨日まで覚えていたのですが…。明日必ず返

しに参ります。」

A! Sensei moushiwake arimasen! Wasurete imashita.

Kinou made oboete itanodesuga…. Ashita kanarazu

kaeshini mairimasu.

Ah! Sir (Lecturer), I’m sorry! I forgot it. But I

remembered until yesterday though… Tomorrow I will

definitely return it (to you).

From example 1, it is shown that the choice of

formal form of Watashi did not stand alone and

supported by honorific ‘Modest form’ (Kenjougo)

such as okaeshisuru (return) and orimasu (be). As

well as example 2, to show higher level of politeness,

address term Sensei used along with ‘Polite form’

(Teineigo) such as -mashita and -desu form, and

with ‘Modest form’ mairimasu (go/come). Address

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

426

terms used by JNS shows formality and tend to

function as politeness strategy. However, the

numbers of address terms use in Japanese are

extremely few compared to the other two languages.

From the cultural anthropology point of view,

addressing someone is similar to ‘touch’ that

someone indirectly, and has an aspect conflicting

with basic taboos (Takiura, 2008). In Japanese it is

said that the impact of this taboo is strong, and this

tendency showed in the result of this study. That

JNS tend to avoid or minimize using address terms

to the addressee, which means minimizing ‘touching’

the hearer. For Japanese that prefer to maintain their

negative face (Ikeda, 1993; Jung, 2011),

minimalizing the use of address terms means

respecting the addressee’s negative face, which also

could be understood as negative politeness strategy.

Meanwhile, INS used two types of ‘Term of self’

which are Saya (416 times) and Aku (2 times) when

the addressees are non-equal. Saya is formal form of

a ‘term of self’, and Aku is rather informal than Saya.

This explains why Saya used in enormous number

while Aku in extremely small number. Since with

non-equal addressees the power or social distance

between addressees and addresser are distant, it is

understood that the respondents felt the necessity to

maintain the distance and the formality which shown

by their use of ‘term of self’. This tendency also

shown by their use of ‘address terms’, that they only

used one type of expression to their ‘lecturer’, which

is Bapak/Ibu (often shorten as Pak/Bu) meaning

“Sir/Ma’am”, for 297 times. This Bapak/Ibu is a

pronominal that originally means “Father/Mother”,

but in communication is generally used to address

someone older, or someone respected regardless of

their age.

Example (3)

(INS8) Pak, maaf saya tidak bisa mengembalikan bukunya

tepat waktu. Apa Bapak tidak keberatan saya

mengembalikannya besok? Saya benar-benar minta maaf.

Sir, I’m sorry I cannot return your book as promised due.

Do you mind Sir if I return it tomorrow? I’m really sorry.

As seen on Example (3), INS used Saya to

address himself and used Pak and Bapak to address

the lecturer. It is seen that the choice of these formal

‘term of self’ and ‘address term’ were used by INS

to show his/her respect to the addressee. The

willingness to show respect to the addressee was

also shown by repeatedly using ‘term of self’ and

‘address term’, and this tendency from INS data is

remarkable.

Meanwhile, when the addresser is equal (friend),

INS used 3 types of ‘term of self’ which are Saya

(103 times), Aku (97 times) and others (18 times).

Interestingly, when the addresser is NF, Saya was

mainly used, but when to IF, Aku was mainly used.

It merely shows the social distance between the

addresser and addressee, that when the distance is

closer, addressee tend to use informal form of ‘term

of self’, but when the distance is further, they tend to

use more formal ‘term of self’.

On the other hand, ‘address term’ used when the

addressee is equal are 4 types which are Kamu (you)

(42 times), Teman (friend) (21 times), Addressee’s

name (13 times), Sayang (or Say in short, means

‘Love’) (7 times). The use of first 3 address terms

did not show much difference on IF and NF, when

Sayang which shows intimate relationship only used

for IF. These shows that addressees tend more freely

to choose and use varieties of address terms to the

equals which has closer social distance than to non-

equals. According to Brown and Levinson (1987),

address forms is an in-group identify markers, which

included as positive politeness strategy. Indonesian

has been stated prefer to maintain their positive face

(Takadono, 2000; Haristiani, 2010). This tendency

proven by the data in this study, where INS tend to

use address terms repeatedly in one utterance and

showed enormous number of address terms use also

in many varieties of expressions overall.

In Sundanese, the form of ‘term of self’ used to

non-equal addressee were 3 types, which are

Abdi/Abi (I) (144 times), Addresser’s name (15

times), and Others (2 times). Abdi means “I”, which

has the honorific meaning. Abdi generally used in

formal situations, which has function to express

respect to the addressee. However, Abi has less

formal meaning, although in this study we did not

differentiate the function between Abdi and Abi.

Meanwhile, the ‘address term’ used by SNS to the

non-equal was similar to INS, which was Bapak/Ibu

(318 times). This address terms have similar

meaning and function to those used in Indonesian,

since those words were originally borrowed from

Indonesian.

Example (4)

(SNS1) Punten Bapak, abi teu nyandak bukuna. Tadi teh

abi rusuh jadi weh hilap. Wios teu pami enjing Pak?

Punten pisan.

Sorry Sir I did not bring the book. I was in a hurry and

forgot about it. Is it OK to return it tomorrow? (I’m) really

sorry.

As seen on Example (4), SNS used Abi to

address himself and used Bapak and Pak to address

the lecturer. Similar to INS, SNS choose these

formal ‘term of self’ and ‘address term’ to show his

Address Terms in Japanese, Indonesian and Sundanese - As Politeness Strategy in Apology Speech Act

427

respect to the addressee. The willingness to show

respect to the addressee was also shown by

repeatedly using ‘term of self’ and ‘address term’,

even though the tendency was not as obvious as INS.

For ‘term of self’ to equal addressee, SNS used

mainly 4 types of ‘term of self’ which are Abdi/Abi

(47 times), Urang (17 times), and others (15 times).

Others were such as Kuring, Aing, etc. Meanwhile

the use of ‘address term’ including Name (12 times),

Maneh (7 times), Bro (shortened from ‘brother’) (7

times), Kang (shortened from Akang means

‘brother’) (5 times), Neng/Eneng (means ‘sister’) (5

times), and others (18 times). This tendency is

similar to INS, when SNS tend more freely to

choose and use varieties of address terms to the

equals which has closer social distance than to non-

equals. These use of address terms in Sundanese also

considered as positive politeness strategy, where

SNS prefer to use address terms to maintain

addressee’s positive face with numerous and

varieties in forms of address terms.

4 CONCLUSIONS

This study observed the use of ‘Term of self’ and

‘Address term’ in ‘Apology’ and ‘Misunderstood’

situations in cross cultural context, which are in

Japanese, Indonesian, and Sundanese. The result

showed that Japanese had different tendency in

using address terms, where in Indonesian and

Sundanese the tendency to use address terms were

more similar. The use of address terms in Japanese

and Sundanese mainly influenced by power relation

(Jougekankei), when in Indonesian it is influenced

both by power relation and familiarity/intimacy

(Shinsokankei). From politeness perspective,

Japanese tend to minimalize using address terms as

their effort to maintain addressee’s negative face as

negative politeness strategy, while Indonesian and

Sundanese tend to use address terms to show their

willingness to respect addressee’s positive face and

use address terms as positive politeness strategy as

many as possible, and this tendency seen most

obvious in Indonesian.

REFERENCES

Abe, K., 2006. Shazai no Nicchuu Taishou Kenkyuu

(thesis). Hiroshima University. Unpublished.

Afful, J.B.A., 2010. Address forms among university

students in Ghana: a case of gendered identities?.

Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural

Development, 31 (5), pp. 443-456.

Boyckman, S., Usami, Y., 2005. Yuujinkan de no Shazaiji

ni Mochiirareru Goyouron teki Housaku : Nihongo

bogo washa to Chuugokugo bogo washa no hikaku.

Goyouron Kenkyuu, 7, pp 31-44.

Braun, F., 1988. Terms of address: Problems of patterns

and usage in various languages and cultures (Vol. 50).

Walter de Gruyter.

Brown, P., Levinson, S.C., 1987. Politeness: Some

universals in language usage (Vol.4). Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge.

Haristiani, N., 2010. Indonesiago to Nihongo no

Shazaikoudou no Taishoukenkyu – Shazaibamen to

Gokaibamen ni okeru feisu no ijihouryaku ni

chakumokushite (Thesis). Hiroshima University.

Unpublished.

Haristiani, N., 2012. Indonesia go to Nihongo no koshou

no hikaku – Shazai bamen ni mirareru jishoushi-

taishoushi no taiguuteki kinou ni chakumokushite.

Sogogakujutsu gakkaishi, 11, pp. 19-26.

Ikeda, R., 1993. Shazai no taishokenkyuu—Nichibei

taishoukenkyuu—face to iu shiten kara. Nihongogaku,

12, pp.13-21.

Jung, H.A., 2011. Shazaikoudou to Sono Hannou ni

kansuru Nikkan Taishoukenkyuu: Poraitonesu riron no

kanten kara. Gengo Chiiki Bunka Kenkyuu, 17, pp. 95-

112.

Kim, M., 2015. Women’s talk, mothers’ work: Korean

mothers’ address terms, solidarity, and power.

Discourse Studies, 17(5), pp.551-582.

Kusumoto, T., 2010. Nihongo no taiwa tekisuto ni okeru

jishoushi-taishoushi no shudaikinou – Chuugokujin

gakushuusha no nihongo ni yoru shotaimen kaiwa kara

no bunseki. Tokyogaikokugodaigakuronshuu, 81, pp.

155-166.

Lee, H., 1991. Nihongo no ninshoudaimeishi no

shouryaku ni tsuite. Kokubun Kenkyuu, 41, pp. 45-55.

Ohama, R., 2001. Nihongo kyoukasho ni mirareru

jishoushi-taishoushi no shiyou ni tsuite. Kyouikugaku

kenkyuu kiyou, 47(2), pp. 342-352.

Rendle-Short, J., 2009. The address term mate in

Australian English: is it still a masculine term?.

Australian Journal of Linguistics, 29(2), pp.245-268.

Suzuki, T., 1976. Kotoba to bunka (Vol. 858). Iwanami

Shoten.

Taavitsainen, I., Jucker, A.H. eds., 2003. Diachronic

perspectives on address term systems (Vol. 107). John

Benjamins Publishing.

Takiura, M., 2008. Poraitonesu Nyuumon. Tokyo:

Kenkyuusha.

Takadono, Y., 2000. Nihongo to Indonesiago no

Iraihyougen no Hikaku. Ajiakenkyuujo Kiyou, 9, pp.

353-357.

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

428