Read, Miscue, and Progress

A Preliminary Study in Characterizing Reading Development in Shallow

Indonesian Orthography

Harwintha Yuhria Anjarningsih

Faculty of Humanities, Universitas Indonesia, Depok, West Java, Indonesia

wintha.salyo@gmail.com

Keywords: Reading Development, Indonesian Orthography, Syllabic Complexity, Children’s Literacy.

Abstract: Understanding what happens when children learn to read Indonesian is very important, in terms of both

advancing psycholinguistics and improving practices that are done in educational institutions throughout the

country. The current study aimed to characterize the normal development of reading in the under-researched,

shallow Indonesian orthography. A total of eighty-two children aged 7-9 years old participated by reading

aloud 100 words that are of high frequency, monomorphemic, disyllabic, and controlled for syllable structure

(simple, diphthongs, digraphs, and consonant clusters). Reading miscues that were committed by the children

showed that simple disyllabic words were mastered at the end of grade one, and diphthongs, digraphs, and

consonant clusters were mastered later. Results are interpreted based on the predictability of the mapping

between graphemes and phonemes in the Indonesian orthography.

1 INTRODUCTION

Orthographic depth, syllabic complexity, word

length, and use of sub-lexical clusters (e.g., (the st in

the word stop and) and digraphs (e.g., the oe in the

word bloem) are explored in the current investigation

with the general aim to assess how syllabic

complexity influences normal reading development

(see Seymour, Aro, and Erskine, 2003; Zoccolotti, De

Luca, Di Pace, Gasperini, Judica, and Spinelli, 2005;

Marinus and de Jong, 2008). Syllabically, the

Indonesian orthography is very transparent,

predominantly CV with the C being simple

consonants such as that found in the disyllabic word

<guru> (‘teacher’). There are just few exceptions in

the mapping between graphemes (i.e., letters) and

phonemes. What can be considered as exceptions are

diphthongs and digraphs, two letters that are

pronounced as one sound. Diphthongs are <ai>, <oi>,

and <au>. Some examples of digraphs are <ng> /ŋ/,

<ny> /ɳ/, and <sy> /ʃ/. Interestingly, although the

words have the same syllabic structure (e.g., CV-CV),

when the consonants are digraphs or the vowels are

diphthongs, readers see more letters written and thus

words containing digraphs and diphthongs are longer

in length than words that contain simple graphemes.

Not only length, mapping two letters into one sound

may also be challenging for the novice readers.

Therefore, there is possibility that words containing

diphthongs and digraphs present some difficulty for

beginning readers.

From phonetics literature, we know that what

diphthongs and digraphs are. Diphthongs are vowel

sounds that contain a glide from one vowel sound to

another (Roach, 2009). The position of the tongue

moves from one position when producing the first

sound to another position when producing the second

sound. For instance, in the diphthong /ai/ which is

represented by <ai>, the diphthong starts with an

open vowel which is between front and back, and

glides to a closed high vowel. Furthermore, digraphs

are two letters that represent one sound (Robbins,

Kenny, and Robbins 2007). For example, in

Indonesian, the letter <n> maps to an alveolar nasal

consonant, and the letter <g> maps to a velar plosive

consonant. However, when <n> and <g> are in a

digraph, they map to /ŋ/ which is a velar nasal

consonant. Another example, the alveolar nasal

consonant which is represented by the letter <n> and

the palatal approximant represented by the letter <y>

are combined in the digraph <ny> which maps to the

palatal nasal consonant /ɲ/. In practice, when

beginning readers are not reading letter per letter and

are instead mapping diphthongs and digraphs to their

corresponding sound, they will be more successful in

Anjarningsih, H.

Read, Miscue, and Progress - A Preliminary Study in Characterizing Reading Development in Shallow Indonesian Orthography.

DOI: 10.5220/0007176208390843

In Proceedings of the Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference

on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education (CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017) - Literacy, Culture, and Technology in Language Pedagogy and Use, pages 839-843

ISBN: 978-989-758-332-2

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

839

reading the diphthongs and digraphs. When children

think that the digraph <ng> are individual letters, for

instance, they may read the word bunga as bun-ga,

still preserving the number of syllables but changing

their structure. When children realize that bun-ga

does not map into any word in their lexicon, they start

to grasp that in order to link the concept of FLOWER

in Indonesian to its written rendering, they need to

pronounce the <ng> as /ŋ/. That is, using the lexical

strategy to read.

Syllable onsets in Indonesian can also be

consonant clusters. In the current investigation, only

clusters comprised of two consonants were included

in the materials, such as the <dr> in the word drama.

This phonotactic pattern is only one of the eight

syllabic patterns of consonant clusters in Indonesian

(Hasibuan, 1996).

The research builds on previous investigations of

miscues made by children (e.g., Goodman, 1969;

Goodman and Burke, 1973) that seek to compare

what the young readers say (observed responses) and

what they read (expected response). By doing miscue

analysis, processes that happen during reading can be

mapped and used to determine factors that influence

reading development in Indonesian. More

specifically, the current work builds on and expands

an earlier work (Anjarningsih 2016) that studied 17

preschoolers and first graders. The most relevant

findings for the present investigation were that at the

grade one level, children’s miscues were

predominantly visual and that the consonant clusters

were the most challenging words to read. Therefore,

this study aims to find out what kind of miscues

happen when children read highly-frequent disyllabic

words containing diphthongs, digraphs and consonant

clusters; to seek what the reading miscues can inform

us about the effects of the spelling of diphthongs,

digraphs, and consonant clusters on children’s

reading development; to propose a possible

underlying reason for the miscues that are committed;

and to propose how sub-lexical factors influence

reading development of highly frequent disyllabic

words.

2 METHOD

This study was a qualitative study involving eighty-

two normally developing children living in Depok,

West Java, Indonesia, of which 46 are boys, and 36

are girls. Miscued words produced by the children

were tabulated and subjected to a qualitative analysis.

3 RESULTS

Based on the miscues that were committed by the

children, three kinds of miscues were identified,

including 1) visual: miscues showing change,

substitution, deletion, and transposition of sounds in

the words. The resulting words still share 50% of its

graphemes (letters) with the tested words; 2)

regularisation: miscues which results in the division

of digraphs and diphthongs into one or two simple

graphemes or sounds; and 3) substitution : miscues

resulting in totally different words or pseudo- or non-

words.

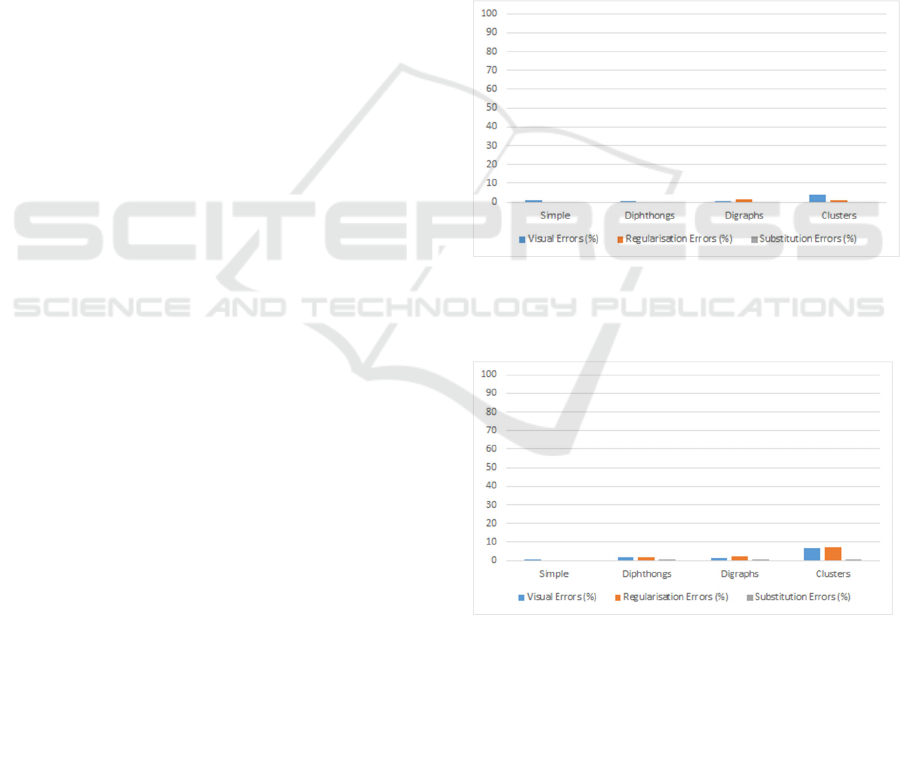

Figures 1, 2 and 3 show the total number of each

kind or miscues and its proportion relative to the total

number of words read per grade.

Figure 1: The total number of each kind or miscues and its

proportion relative to the total number of words read by

grade 1 students (n=19 children).

Figure 2: The total number of each kind or miscues and its

proportion relative to the total number of words read by

grade 2 students (n=43 children).

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

840

Figure 3: The total number of each kind or miscues and its

proportion relative to the total number of words read by

grade 3 students (n=20 children).

Within each grade and each kind of miscues, a

paired t-test was run, comparing the number of

miscues committed to the shorter words and that

committed to the longer words. In total, nine paired t-

tests were run, and none of the ps was 0.05 or lower.

This means that there was no statistically significant

difference between the reading performance of the

children when they read the shorter words in all word

groups and the reading performance of the children

when they read the longer words in all word groups.

Comparing the three grades, the youngest readers

made proportionately more miscues than the older

ones who had practiced reading longer. This was true

for all kinds of miscues.

Simple words that simulated the transparency of

the Indonesian orthography were read very

successfully early on. Nobody substituted the simple

words with other words that do not share at least 50%

similarity in spelling. Diphthongs were also quite

successfully read from first grade on, as reflected by

the less than 5% miscue rate per kind of miscue. In

first grade, children made more substitution miscues

(e.g., reading tunai as bumi), but in second grade, the

most committed miscue was regularization (e.g.,

reading da-mai as da-ma), followed very closely by

visual miscues (e.g., reading wahai as wati). In the

third grade, accuracy in reading words with

diphthongs reached ceiling.

Comparing diphthongs and digraphs, in first and

second grade, overall rate of miscues of diphthongs

and digraphs are comparable. However, in third

grade, diphthongs were read with virtually almost no

miscues (i.e., 0.20%), whereas digraphs were

miscued 1.80%. It may very well be that digraphs

were mastered later than diphthongs and that the

second grade is a kind of cut-off grade: after learning

to read for two years, children understand that the

double letter of diphthongs map to single vowel

phonemes, but at the same time, it is still more

challenging to map the two letters of digraphs to

single consonant phonemes.

Of the four groups of words, the consonant

clusters group proved to present the most challenge

for the young beginning readers. Although the

percentage of miscues of this group of words declined

as the grades advanced, in third grade children made

comparably more miscues to words in this group than

to words in the other three groups. In general, children

made at least twice as many miscued consonant

clusters as miscued digraphs.

On closer inspection, in grades one and two, for

digraphs and consonant clusters, the kind of miscue

that was produced the most frequently was

regularization. Recall that this is when readers

separated the letters in the digraphs and when the two

letters in the consonant clusters are read as if they

were single letters (e.g., reading krisis as kirisis.). In

grade three, digraphs were still predominantly

regularized, but consonant clusters were

predominantly read as other words that differ from

the intended words in as much as at least 50% of their

letters.

4 DISCUSSION

The study’s main goal was to characterize the reading

development of normal Indonesian children. In doing

so, the materials were designed to capture both the

regularity of the transparent Indonesian orthography

and some irregularities that exist in the orthography

in order to see how such irregularities influence

reading development. To answer the first research

question, from the sample of young readers, miscues

were identified when they read disyllabic words

containing diphthongs, digraphs and consonant

clusters and three kinds of miscues were found:

visual, regularization, and substitution. Up to the

second grade, diphthongs and digraphs are mostly

regularized and in the third grade, only digraphs are

regularized. A higher proportion of miscues still

happen to consonant clusters, compared to those to

digraphs, even in the third grade. Therefore, in the

children’s reading development, it seemed that they

went through a process, begun by successfully

mastering words with simple spelling, followed by

mastering words with diphthongs, digraphs and

consonant clusters consecutively.

As for the answer to the second research question,

the manipulation to the syllabic structure showed that

children went through a process in mastering

common words. They were not at the same time able

to read all disyllabic words that were given. The same

number of letters that constitute diphthongs and

Read, Miscue, and Progress - A Preliminary Study in Characterizing Reading Development in Shallow Indonesian Orthography

841

digraphs did not seem to have the same effect on the

order when they are mastered. Diphthongs seemed to

be mastered at the end of the second grade, while

digraphs were still a little difficult at the end of the

third grade. Therefore, having the same number of

letter does not seem to be the only factor at play.

Another factor seems to be the ease at which children

grasp the mapping between the diphthongs and

digraphs on the one hand, and the phonemes on the

other hand. It is proposed that the earlier mastery of

diphthongs is because the glide in diphthongs may

have been easier to understand by children due to the

transparent mapping between the two glided sounds

and the two letters in the diphthongs.

The digraphs, in turn, may have been more

difficult because the sounds that the digraphs map to

are not directly evident. There are two possible routes

to memorizing this mapping: analysis and

memorization. The children may have analyzed, in

the case of the digraph <ng>, the letter <n> maps to

an alveolar nasal consonant, the letter <g> maps to a

velar plosive consonant, and <ng> map to /ŋ/ which

is a velar nasal consonant, a consonant with the same

manner of articulation as /n/ and the same place of

articulation as /g/. There are features that are shared

by /n/ and /g/ on the one hand, and /ŋ/ on the other

hand. Once children have done the analysis and

arrived at the correct conclusion based on a good

match with an entry in their lexicon, they may have

started to remember, for instance, the pairing between

the written word <bunga> with the lexical entry

bunga in their lexicon. This memorization may then

lead to them reading not the single letters of the

diphthongs, but the phoneme that each of the

diphthongs maps to.

Consonant clusters seemed to present the ultimate

difficulty as shown by the findings that at the end of

third grade, children still made considerable

proportion of miscues to words containing consonant

clusters. A possible explanation is because there are

many more consonant clusters than there are

diphthongs and digraphs, children took longer to

establish the mapping between consonant clusters and

the phonemes that they represent. In other words, the

greater number of kinds of consonant clusters adds

more challenge, in addition to the clusters having two

graphemes which render the clusters having more

sounds than diphthongs and digraphs.

The above findings go along the lines of those of

Marinus and de Jong (2008). Although using a

different method, it was demonstrated that digraphs

are utilized by beginning readers when they read and

they do influence the details of the syllable structures

that are mastered by children as they progress from

grade one to grade three of primary school.

Furthermore, findings about word length effect that

has been observed previously was also observed in

the current investigation. In line with Zoccolotti et al.

(2005) end of grade three seemed to be the point at

which children are not very much influenced by the

longer diphthongs and digraphs. In addition, the

current results expand the work of Anjarningsih

(2016) in that the consonant clusters continue to

present challenges even up to the end of grade three.

However, the findings about consonant clusters

may raise some questions before they can be

confidently interpreted. There is of course a

difference between digraphs and diphthongs on the

one hand, and consonant clusters on the other hand:

while diphthongs and digraphs map to one phoneme,

consonant clusters map to two or more phonemes, one

for each of the graphemes or letters in the clusters.

While this mapping, intuitively, may seem to predict

that consonant clusters should be easier to master than

digraphs because once children can map single

consonant graphemes to their corresponding

phonemes, they should get the pronunciation of

clusters correctly, our current findings go against this

prediction. Whether the visual and regularization

miscues were caused by children expecting to find

simple consonants followed by simple vowels in

syllables remains to be tested further.

With the above findings at hand, it interesting to

see that children did not master all the tested

disyllabic words at about the same time. They needed

to practice reading for about three years before their

reading performance became accurate. The sub-

lexical details or in this case, the syllabic make-up of

the words did influence how accurate children read

the words. Therefore, in a transparent orthography

such as the Indonesian orthography investigated here,

the mapping between graphemes and phonemes in

“irregular” diphthongs, digraphs, and consonant

clusters influences how early children can read

highly-frequent disyllabic words. Syllabic

complexity and orthographic depth, just like the

findings of Seymour et al. (2003), also influence the

rate of reading development in Indonesian.

It should be noted that the syllabic structures

tested in the current investigation do not comprise all

syllabic structures in Indonesian. In addition to CV or

CVC, Indonesian also has VC which can be written

by vowel and consonant graphemes or just vowel

graphemes (e.g., in the word <dua> meaning “two,”

the grapheme <a> maps to /wa/). Furthermore,

trisyllabic and words with more syllables also exist in

Indonesian, both monomorphemic (e.g., udara “air”)

and polymorphemic (e.g., penggorengan “frying

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

842

pan”). Future research should incorporate other

syllabic structures and longer words in order to map

the reading development of Indonesian children more

thoroughly.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In this research that aims to characterize the

development of reading in normally-developing

Indonesian children, three kinds of reading miscues

were committed by the participants: visual,

regularization, and substitution. These miscues

helped to highlight that digraphs were mastered some

time after the children could read diphthongs

accurately (end of grade 3 vs. end of grade 2), and

consonant clusters were also mastered later that

digraphs. The different paths of acqusition between

diphthongs and digraphs were explained by how

predictable the mapping was between the diphthongs

and digraphs and their sounds. For consonant clusters,

the more time it took the children to master them was

attributed to the existence of much more consonant

clusters than digraphs that could have extended the

time children needed to map the clusters and their

sounds accurately. It is shown by the current results

that sub-syllabic complexity influenced the paths of

reading acqusition of frequent disyllabic Indonesian

words.

REFERENCES

Anjarningsih, H.Y. 2016. Characterizing the Reading

Development of Indonesian Children. In Yanti (ed.).

Kolita 14: Konferensi Linguistik Tahunan Atma Jaya

Keempat Belas. Paper presented at the Konferensi

Linguistik Tahunan Atma Jaya Keempat Belas, Unika

Atma Jaya, Jakarta, 6-8 April, 2016 (pp. 156-159).

Goodman, K.S. 1969. Analysis of Oral Reading Miscues:

Applied Psycholinguistics. Reading Research

Quarterly, 5, 9-30.

Goodman, K.S., Burke, C.L. Theoretically Based Studies of

Patterns of Miscues in Oral Reading Performance.

Wayne State Univ.: Detroit, Mich.

Hasibuan, N.H. 1996. Fonotaktik dalam suku kata bahasa

Indonesia. Depok: Fakultas Ilmu Pengetahuan Budaya

Universitas Indonesia (unpublished master’s thesis).

Marinus, E., de Jong, P.F. 2008. The Use of Sublexical

Clusters in Normal and Dyslexic Readers, Scientific

Studies of Reading, 12, 253-280.

Roach, P. 2009. English Phonetics and Phonology. 4

th

edition. Cambridge: CUP.

Robbins, L. Kenny, H.A., Robbins, L. A. 2007. A Sound

Approach: Using Phonemic Awareness to Teach

Reading and Spelling. Portage & Main Press.

Seymour, P.H.K., Aro, M., Erskine, J.M. 2003. Foundation

literacy acquisition in European orthographies. British

Journal of Psychology, 94, 143–174.

Zoccolotti, P., De Luca, M., Di Pace, E., Gasperini, F.,

Judica, A., Spinellli, D. 2005. Word length effect in

early reading and in developmental dyslexia. Brain and

Language, 93, 369-373.

Read, Miscue, and Progress - A Preliminary Study in Characterizing Reading Development in Shallow Indonesian Orthography

843