Phishing Through Time: A Ten Year Story based on Abstracts

Ana Ferreira and Pedro Vieira-Marques

CINTESIS, Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal

Keywords:

Phishing Trends, Systematic Literature Review.

Abstract:

For a researcher interested in phishing, it would be useful to access an overview of phishing evolution through

time, where a set of methods, tools, solutions, user studies, type of attacks, countermeasures and so on, could

be acquired from a single story. This story is essential for the security community to improve on existing

research as well as build new effective countermeasures to face phishing attacks. However, no systematic

review exists in the literature providing a wide overview of all phishing topics. Available reviews usually

focus on one or two at a time. In fact, since there is widely available and varied literature on phishing, making

a comprehensive review can take a long time and be cumbersome. This paper describes a method to perform a

review on abstracts of 605 scientific papers selected from major online research databases, between 2006 and

2016. The study uses a qualitative categorization software to, for the first time, achieve a story of phishing

trends in its existing research strands for that period. According to obtained results, no single solution for the

phishing threat could yet be found and most research is turning now into more integrated socio-technical and

human related solutions.

1 INTRODUCTION

The more we use technology as the main way of com-

municating, the more phishing is bound to grow as

well as become more sophisticated and adaptive, and

this can happen independently of the users’ technolo-

gical literacy (Hong, 2012) (Boodaei, 2011). To look

more appealing and trustworthy, phishing makes use

of a plethora of persuasive elements (Harrison et al.,

2015) carefully framed to make the message sound

personal and mimicking normal/real daily communi-

cations and interactions. Examples of these are phis-

hing emails that contain links: new research suggests

that whoever is used to social networks is less cauti-

ous and more likely to click on active links (Dutton,

2015).

A recent study confirms that phishing is far more

successful and more professionally exploited than

commonly thought (Bursztein et al., 2014) so we

need better means to understand the phishing process

and characteristics so that effective countermeasures

are taken to improve employees’ ability in the deci-

sion making process (Ma, 2013). A deeper under-

standing of victim’s profiles, types of attacks, phis-

hing tools, methods and user studies to identify what

makes phishing attacks so successful is essential for

the security community to be able to focus resour-

ces to build more adequate and effective countermea-

sures (Hong, 2012).

Such comprehensive scientific knowledge can be

obtained with literature reviews which summarize

current knowledge into a particular field and inter-

pret that knowledge and the information-organizing

spectrum upon which researchers depend in order to

stay informed (Schultz, 2011). However, the aut-

hors could not find such review in the literature regar-

ding phishing. This can be explained by the fact that

there is widely available published research on the to-

pic and its various subjects and such exhaustive rese-

arch would imply a lot of time and resources and be-

come this way a very cumbersome task. Existing re-

views focus on more specific phishing subtopics such

as: countermeasures and their effectiveness (Purkait,

2012) or current state of phishing approaches (Zeydan

et al., 2014).

With this in mind, this paper describes a method

to perform a review on abstracts only, of 605 scien-

tific papers selected based on queries performed to

the major online research databases, between 2006

and 2016. The study uses a qualitative categorization

software, introduced in the Methods section, to help

deriving from the abstracts the categories and subca-

tegories that will structure and aggregate the various

themes mentioned in the articles. This review provi-

des, for the first time, a story of phishing trends for the

past ten years, in all its existing research strands. The

Ferreira, A. and Vieira-Marques, P.

Phishing Through Time: A Ten Year Story based on Abstracts.

DOI: 10.5220/0006552602250232

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2018), pages 225-232

ISBN: 978-989-758-282-0

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

225

result of this review can provide useful recommenda-

tions and support regarding future phishing trends as

well as research requirements and directions.

Next section describes the methods used to collect

and analyse the articles and respective abstracts inclu-

ded in the review while section 3 presents the results

obtained. Section 4 details a discussion on phishing

trends research overtime and the last section conclu-

des the paper.

2 METHODS

2.1 Query Search

The terms used in order to search for the articles

regarding phishing attacks were: phishing and so-

cial engineering in IEEE, ACM, Thomsom Reuters

and Scopus databases; and phishing review, in IEEE,

Thomsom Reuters and Scopus databases.

We used more general terms because we aimed

to perform a comprehensive review on the theme an

get a bigger sample with a wide range of subjects.

Papers were selected according to titles and abstracts,

written in english, ranging from 2006 to 2016, which

mentioned the topic in study.

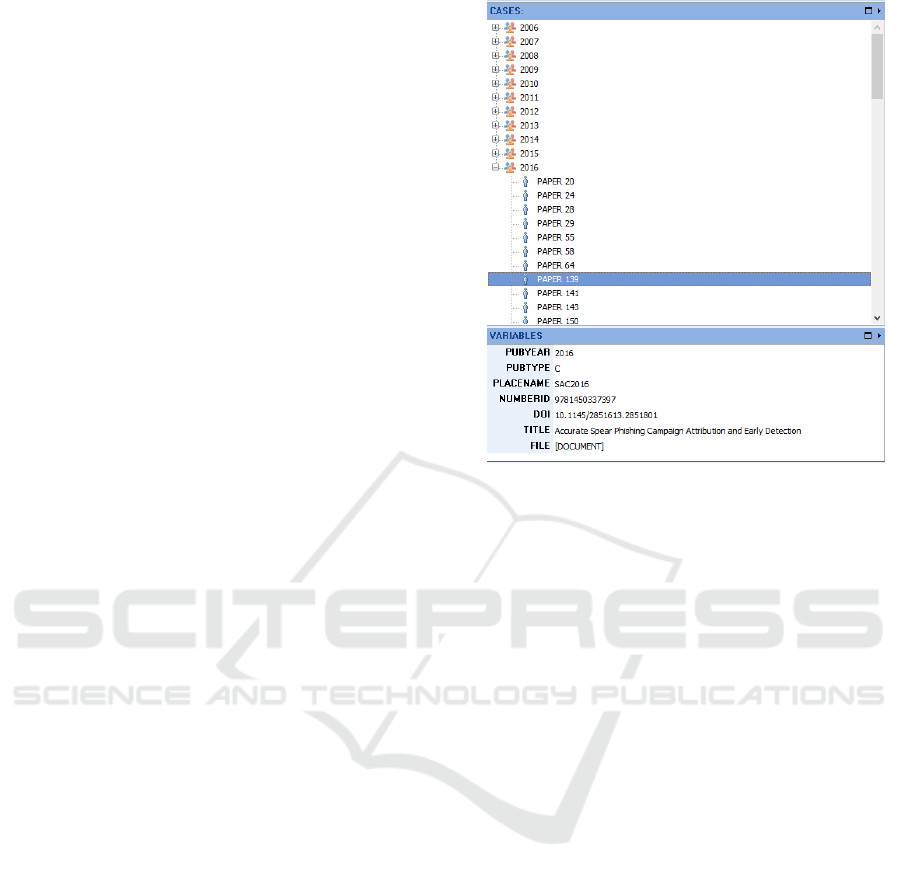

2.2 Cases and Variables

Selected papers were imported to Mendeley manage-

ment database so that they could be exported with the

same structure to a txt file, which included the fol-

lowing tags: TY - type of publication; T1 - title of

publication; A1 - authors; Y1 - year of publication;

JF - Name of the place of publication; SN - ISSN or

ISBN; DO - DOI reference; and N2 - abstract.

This structured data was then imported to QDA

Miner Lite - a free qualitative data analysis soft-

ware (Provalis, 2017) - and each article was transfor-

med into a CASE with several variables such as: PU-

BYEAR, PUBTYPE, PLACENAME, NUMBERID,

DOI, TITLE and FILE. A FILE contains all the con-

tent of the variables and all cases were grouped by

year (Figure 1).

During this process, repeated articles, with the

same title and abstract or those that did not refer to

the topic at hand, were eliminated.

2.3 Coding Abstracts

For each abstract of each case, codes (categories)

were created while data were analysed, using the

technique of line-by-line coding (Eaves, 2001), adop-

Figure 1: Example of variables of a case.

ted from Grounded Theory research. With this techni-

que, we can highlight key term phrases that describe

or focus on the subject we are studying. In the case

of this review we can highlight the objective of the

article, e.g., if it is a study, a review, a discussion or

the implementation of a new technology. Other hints

such as the knowledge acquired during research that

were referred by the authors regarding the main theme

were also highlighted. Line-by-line coding helps to

identify gaps, define actions and explicate both acti-

ons and meanings, which therefore lead to developing

categories. In QDA software, selected text is high-

lighted and a different color can be associated to it.

Every code appears on the right hand side in the posi-

tion where the text appears (Figure 2).

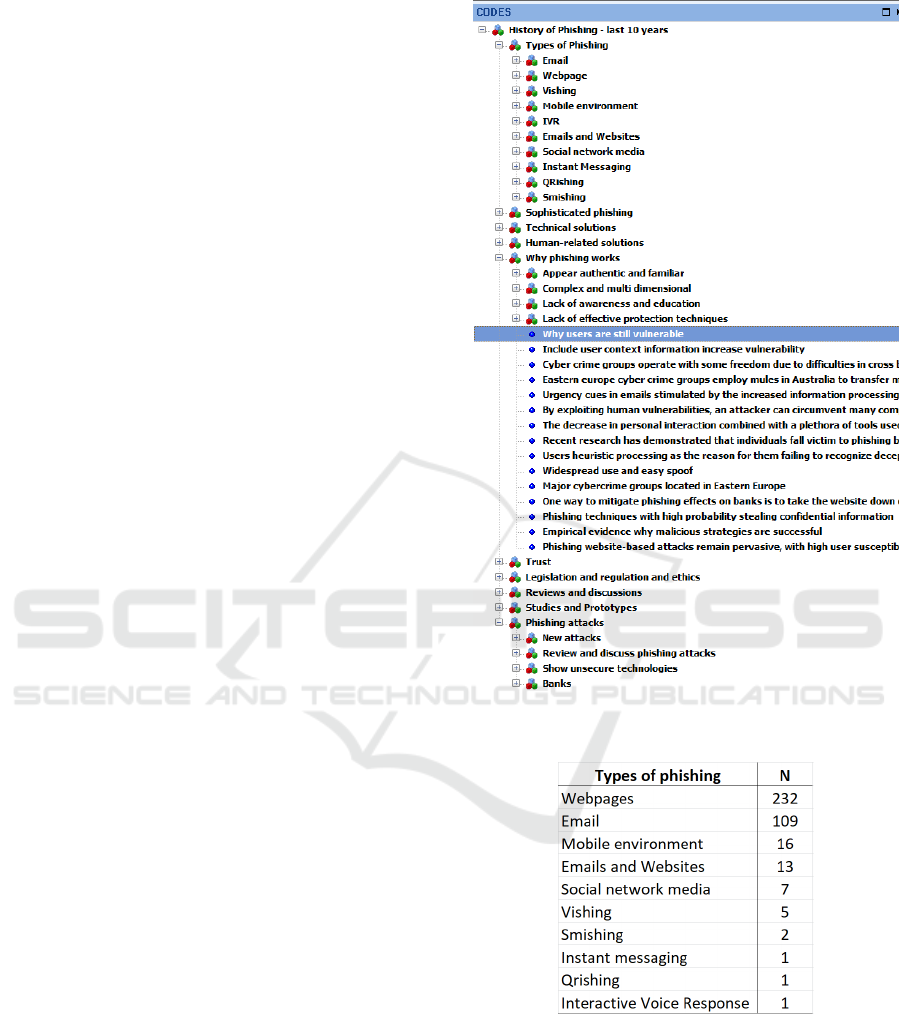

During the review, categories and subcategories

were generated and developed into meaningful clus-

ters. At the end of the review, since there was a high

volume of codification and categories, a specific fo-

cus was made on re-reading and restructuring all the

obtained categories, while repeated and/or misplaced

ones were eliminated and/or re-categorized.

2.4 Analysis

Data for analysis were exported to excel files that con-

tained categories/subcategories, which papers these

related and how many times they appeared. After this,

we analysed both frequencies and trends of those ca-

tegories/subcategories overtime and summarized the

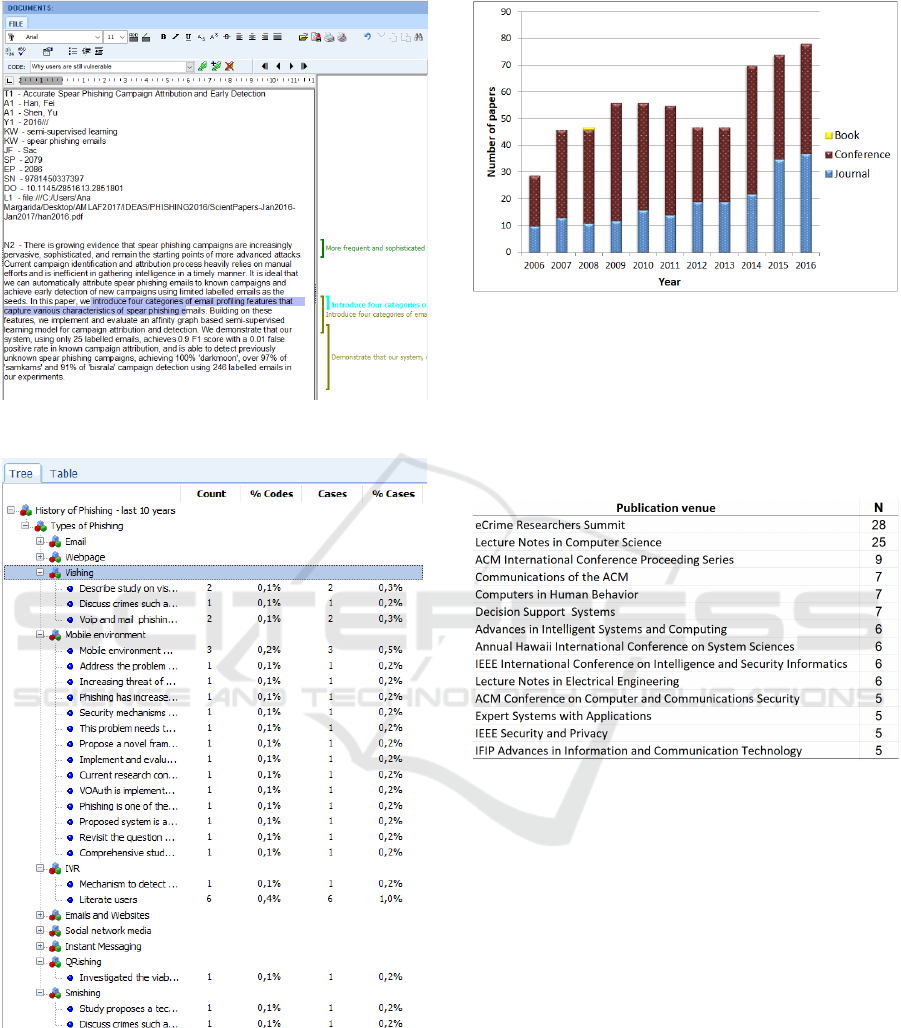

results. Figure 3 shows how the number of codes and

related cases are stored within QDA.

ICISSP 2018 - 4th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

226

Figure 2: Example of line-by-line coding in QDA software.

Figure 3: Illustration of the number of coding lines per ca-

tegory.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Sample Characterization

The analyzed sample included 605 abstracts with a

yearly distribution presented in Figure 4. They mostly

Figure 4: Sample distribution by year and type of publica-

tion, e.g., an article on a journal, a conference or a book.

correspond to conference and journal papers.

Papers of selected abstracts are published in a

wide variety of venues with different themes. The ve-

nues with more than five of those papers published are

presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Sample distribution by year and type of publica-

tion, e.g., an article on a journal, a conference or a book.

3.2 Frequency Analisys

The 10 main categories (and associated subcategories

when these exist) that were generated from the ab-

stract analysis are illustrated in Figure 6. The com-

plete list is the following:

• Types of phishing: email; webpage; vishing; mo-

bile environment; IVR - Interactive Voice Re-

sponse; emails and websites; social network me-

dia; instant messaging; QRishing (phishing using

QR codes) and smishing (phishing using SMS

messages);

• Sophisticated phishing

• Technical solutions: authentication-based;

cryptography-based; Baesyan, data mining,

heuristics, machine learning, decision trees, clas-

sifiers and clustering; white-black and other lists;

Phishing Through Time: A Ten Year Story based on Abstracts

227

visual characteristics; fuzzy logic; honeypots;

IDS - Intrusion Detection Systems; plug-in;

feature extraction; mobile context; biorelated and

insufficient technical measures;

• Human-related solutions: games for training;

education-training and awareness and existing so-

lutions not enough;

• Why phishing works: appear authentic and fami-

liar; complex and multi-dimensional; lack of awa-

reness and education; lack of effective protection

techniques;

• Trust

• Legislation, regulation and ethics

• Reviews and discussions: phishing characteris-

tics; antiphishing measures; users and phishing

and trends;

• Studies and prototypes: user studies; tech stu-

dies to validate tool accuracy; complementary

tools and bank environment;

• Phishing attacks: new attacks; review and dis-

cuss phishing attacks; show unsecure technolo-

gies and banks.

There are also other subcategories that are atta-

ched to the main ones without a subsequent catego-

risation. The totals for each category are presented

next.

For the category Types of phishing, most phis-

hing research focuses on webpages (Figure 7).

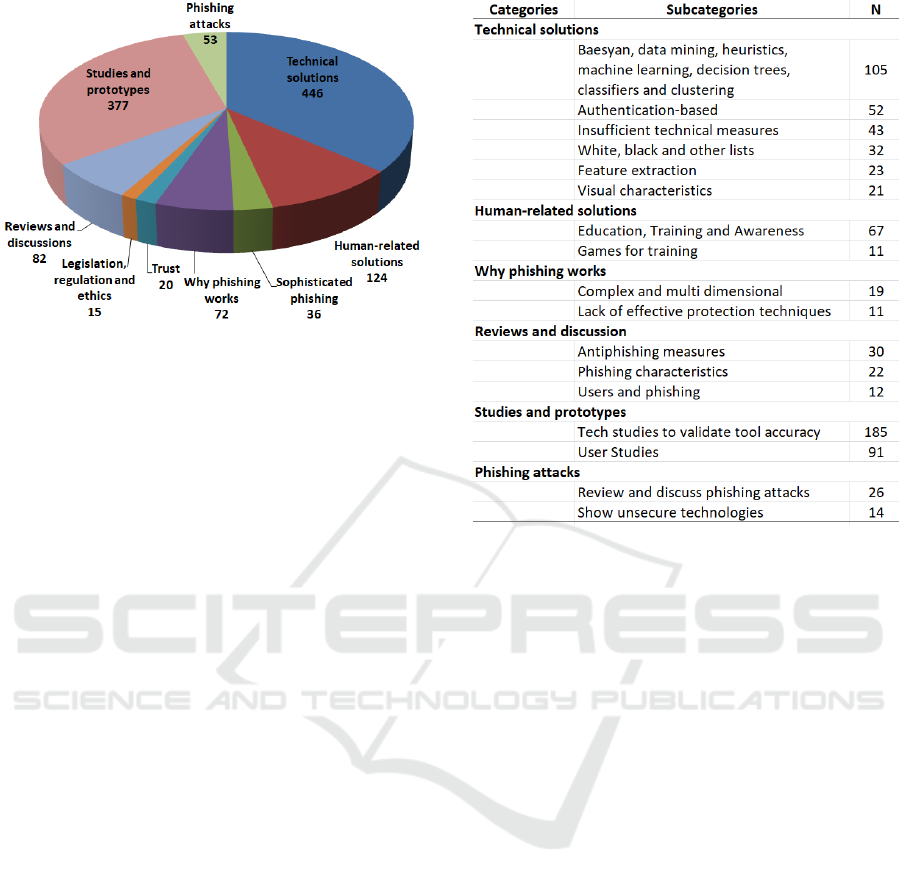

For the other nine main categories, Figure 8 shows

that most papers present technical solutions and with

some sort of study or prototype to evaluate and test

those solutions for efficacy and accuracy. There is

also a big part of human-related solutions as well as

reviews and discussions.

Regarding now the most common subcategories,

Figure 9 describes them within their main categories

together with their frequencies.

In the following paragraphs, uncategorised cate-

gories are those categories that were not aggregated

into a specific subcategory but are still part of the

main category. An example can be seen in Figure 3

where the highlighted category belongs to the main

category Why phishing works but is not aggregated

into any other cluster.

Figure 9 shows that for the category Technical

solutions most new developments are made using

methods like Bayesian, data mining, heuristics, ma-

chine learning, decision trees, classifiers and cluste-

ring, followed by authentication-based, complemen-

ted with the reference that technical measures are still

not enough to solve the problem. There are also

Figure 6: Main categories generated from the review of the

abstracts.

Figure 7: Number of abstracts focusing on the various types

of phishing, 2006-2016.

129 uncategorised categories within this main cate-

gory.

In Human-related solutions the most common

subcategory refers to Education, training and awa-

reness and Gaming training, while there are also 42

uncategorised categories.

ICISSP 2018 - 4th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

228

Figure 8: Total number of coded lines within the analysed

abstracts for the main categories and most common subca-

tegories.

For Why phishing works, the most common

subcategories relate to complex and multidimensional

characteristics of phishing attacks and also the lack

of effective protection techniques. There are also 25

uncategorised categories.

The main category Reviews and discussion has

the most common subcategories antiphishing measu-

res, phishing characteristics and users and phishing,

while 91 categories remain uncategorised.

For Studies and prototypes, tech studies to vali-

date tool accuracy and user studies are the most com-

mon, with 91 uncategorised categories.

Finally, for Phishing attacks, the most common

subctegories are review and discuss phishing attacks

and show unsecure technologies.

Now regarding the uncategorised categories, the

most common ones are Increased sophistication,

Black lists a not good enough, presented technolo-

gical solutions are Better than existing ones and that

Trust is shattered by phishing.

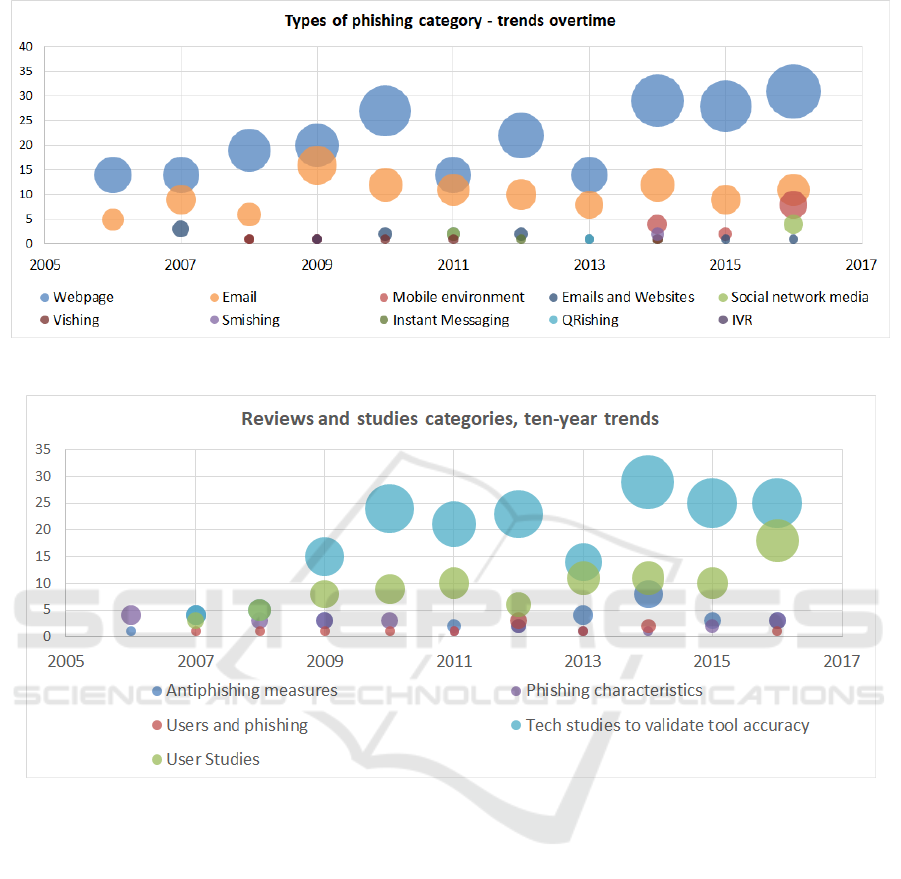

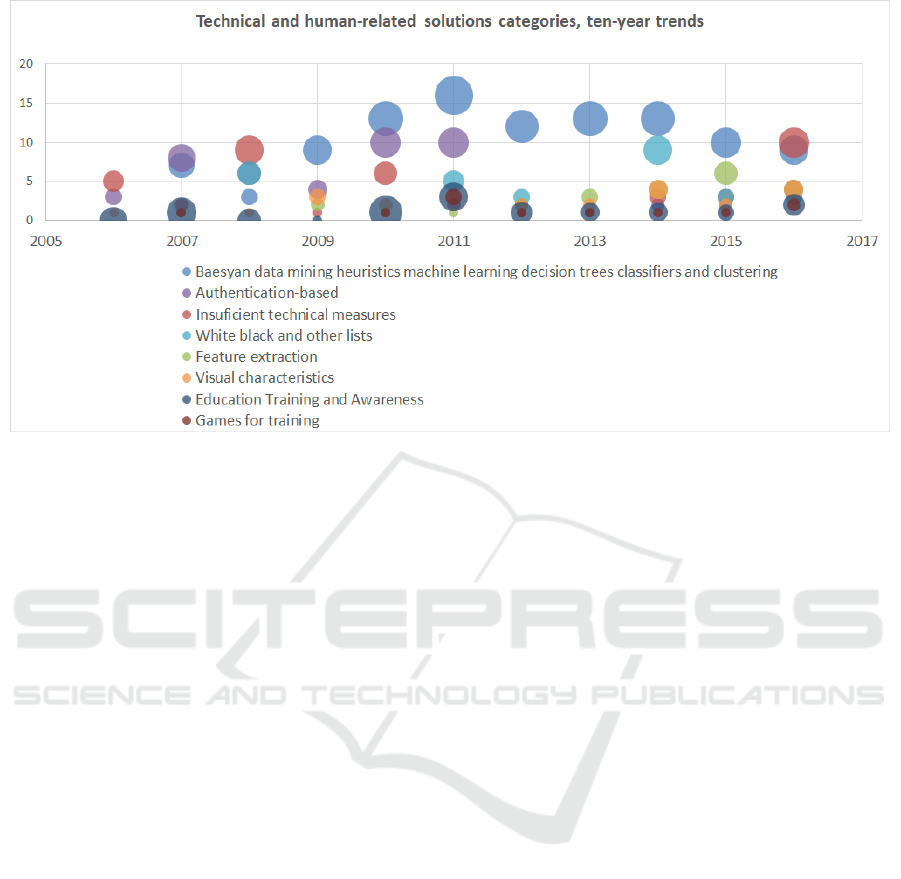

3.3 Ten-year Trends

In order to evidence how categorized items evolve

through time, papers were grouped by year and cate-

gory. A bubble graph was produced representing the

trends along the ten-year review. The circle size was

defined using the number of categorizations per year.

Due to space constraints and visual limitations, Fi-

gures 10 to 12 only show trends for the most com-

mon categories/subcategories, which were introduced

in Figure 9. Succintly, those figures illustrate that

research on webpages, mobile technology, social net-

works (Figure 10), and technological and user studies

(Figure 11) have been recently increasing while an-

tiphishing reviews/studies (Figure 11) as well as Bay-

Figure 9: Total number of abstracts and coded lines for the

main categories.

esian, classification and similar methods (Figure 12)

have been decreasing.

Furthermore, education, training and awareness as

well as the use of games for training research have

been going hand in hand with a slight increase in the

last year while the reference to insufficient technical

measures have been made within the first three years

of analysis then was hardly mentioned in the research

but reappeared with a high increase in the last year

(2016) (Figure 12).

A more detailed discussion and analysis will be

presented in the next section.

4 DISCUSSION

This study aims to provide a ten-year story regarding

phishing research based on abstract analysis only. We

decided to use a qualitative approach based on groun-

ded theory and line-by-line coding so not to limit data

and their categorization from the start but to wait for

these to come up from the analysed sample itself, wit-

hout much restrictions but for the order/clustering the

researcher gives to the codes.

The used software, QDA, is a free version that al-

lows to insert descriptive data regarding each case,

and text or documents associated to that case. For our

purpose, this version of software was easy to install

Phishing Through Time: A Ten Year Story based on Abstracts

229

Figure 10: Types of phishing, ten-year trends.

Figure 11: Reviews and studies, ten-year trends.

and use allowing a quick way to code and structure

categories that were being generated. It is also easy

to summarize frequencies as well as relate cases with

coding results.

Regarding the used sample, we could only verify

its heterogeneity once the review was completed. It

was possible to achieve a variety of categories and

subcategories that show how research themes in phis-

hing have been handled. The sample was well dis-

tributed regarding both journal and conference publi-

cations and is even possible to see that the early ten-

dency of more publications in conferences is getting

more balanced in the last few years by half of the pa-

pers being published in journals and the other half in

conferences. In total, papers on phishing have almost

tripled over the past ten years. This can be explained

by the fact that this problem is far from being solved

and a high number of different positions and approa-

ches have been tried since. Also, in some categories

such as technical solutions and technical studies, the

difference in the place where this type of articles are

published is accentuated as the publications in con-

ferences are double and sometimes almost three ti-

mes of the ones in journals. Generically, most com-

mon venue is the APWG eCrime Researchers Summit

while for user studies and solutions the most common

is the journal Computers in Human Behaviour and for

technical solutions and studies the most common ve-

nues are security related ACM conferences and the

Computers and Security journal. Moreover there is

a high number and variety of themes and publication

venues, both journals and conferences, which shows

that this subject can interest a very heterogeneous au-

dience.

Focusing now on the main themes that were ex-

tracted from the analysis, it is to be noticed that most

ICISSP 2018 - 4th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

230

Figure 12: Technical and human-related solutions, ten-year trends.

research is applied to phishing via webpages since

this is the most common mean of fraud that target ho-

mebanking or email account users. Although there is

much fraud via email, most of the times, the way to

get credentials and personal data is via the filling of a

web form in sites that mimic legitimate pages. It also

makes sense that one of the current growing research

strands relate to mobile environment and the threats

that are associated with it. Its specific characteris-

tics and security flaws can exacerbate in some way the

already existing phishing issues in ”older” technolo-

gies. The same is true for social network media as

seen in Figure 11.

One main category that stands out is the one re-

garding technical solutions. This category is the

most common with almost four times entries than the

human-related solutions although with very little en-

tries before 2009. Despite this, the other categories

remain in much smaller number apart from the stu-

dies and prototypes which is explained by the fact that

most technical and human solutions articles present

some form of evaluation and testing. Similarly, user

studies are around half of the technical studies. Ho-

wever, trends show that user studies have doubled last

year (Figure 12). A reason may be that although there

exist many attempts to implement the perfect techni-

cal solution(s) to solve the problem of phishing, it

seems that the research community is trying to turn

a page and focus on understanding better this socio-

technical complex security problem. Better under-

standing users’ interactions with technology and spe-

cially with phishing attacks can possibly lead to more

effective countermeasures.

To back these data up is the fact that focusing

on antiphishing measures discussion, authentication-

based solutions as well as technical solutions that fo-

cus on Bayesian, data mining, heuristics, machine le-

arning, decision trees, classifiers and clustering (the

second most common subcategory in the whole sam-

ple) have considerably decreased in recent years (Fi-

gures 11 and 12). Furthermore, in Figure 12, there

is another category - insufficient technical measures

- that stands out. Trends show that there have been

some statements related to it in the first half of the

analysed period but it has reappeared with high visi-

bility only in 2016.

Although user studies and the awareness that

technology based only solutions are not enough to

solve phishing attacks, there is a very small increase

in 2016 regarding education, training and awareness

solutions. There is a tendency for the development of

game-based training solutions which may be because,

once more, mobile environment is growing fast and

the possibility of game-based applications that can

tackle social-engineering are at least to be tried and

evaluated.

Limitations. For this study, the Lite version of

QDA software did not allow for extensive analysis fe-

atures so we had to use excel to accelerate the process.

Also, an import functionality was not available which

much delayed the analysis phase since every abstract

(CASE) and related data had to be entered manually.

Still, the frequency analysis that was needed at this

point was achieved with other available tools. Due to

Phishing Through Time: A Ten Year Story based on Abstracts

231

space constraints it was not possible to further detail

and analyse obtained results.

Another limitation of this work was the fact that

only one reviewer was available to perform all the co-

ding. With all the disadvantages this can have, there

is also some advantages since this was a qualitative

coding analysis, it is most likely that the same person

will categorise similar data in the same way. Also to

notice that results are biased or limited by the content

of the abstracts, which, sometimes, may not clearly

state what is really presented within the full article.

However, analyse other parts of the paper such as the

introduction or the conclusion would make the pro-

cess even more time consuming and complex.

Finally, although the used method was still cum-

bersome and time consuming, if there is the possi-

bility of using a complete set of qualitative analysis

software, automatic importing data and detailed ana-

lysis features, the process will be much faster which

then can leave more time for coding as well as cate-

gory generation and structuring.

5 CONCLUSION

This paper gives an overview of phishing research

trends over a ten year period based on the review of

abstracts only. According to obtained results and sub-

sequent analysis, the authors believe that it is clear

that no single solution can be found for the phis-

hing threat. Future research needs to focus on socio-

technical and integrated solutions that can reflect a

comprehensive understanding of both human compu-

ter interactions and users’ unique characteristics as

well as the application and proper testing of advanced,

resilient and human adaptable security technology so-

lutions.

Future work includes performing more detailed

analysis using a more complete qualitative software

that can provide more views on the results and possi-

ble relations that have escaped on the first analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research is supported by NanoSTIMA - Macro-

to-Nano Human Sensing: Towards Integrated Multi-

modal Health Monitoring and Analytics (NORTE-01-

0145-FEDER-000016).

REFERENCES

Boodaei, M. (2011). Mobile users three times more vulne-

rable to phishing attacks. Accessed March 2015.

Bursztein, E., Benko, B., Margolis, D., Pietraszek, T., Ar-

cher, A., Aquino, A., Pitsillidis, A., and Savage, S.

(2014). Handcrafted fraud and extortion: Manual ac-

count hijacking in the wild. In Proc. of 2014 Conf. on

Internet Measurement Conference (IMC ’14), pages

347–358, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Dutton, J. (2015). The psychology behind why we fall for

phishing scams. Accessed March 2015.

Eaves, Y. (2001). A synthesis technique for grounded

theory data analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing,

35(5):654–63.

Harrison, B., Vishwanath, A., Jie, N., and Ragov, R. (2015).

Examining the impact of presence on individual phis-

hing victimization. In Hawaii International Confe-

rence on System Sciences.

Hong, J. (2012). The state of phishing attacks. Commun.

ACM, 55(1):74–81.

Ma, Q. (2013). The process and characteristics of phishing

attacks: A small international trading company case

study. Journal of Technology Research, 4:1.

Provalis, R. (2017). Qda miner lite - free qualitative

data analisys software. Accessed on 27 July 2017:

https://provalisresearch.com/products/qualitative-

data-analysis-software/freeware/.

Purkait, S. (2012). Phishing counter measures and their ef-

fectiveness - literature review. Information Manage-

ment and Computer Security, 20(5):382–420. cited

By 23.

Schultz, T. (2011). Preface. White paper - Annual Review

of Entomology.

Zeydan, H., Selamat, A., and Salleh, M. (2014). Current

state of anti-phishing apapproach and revealing com-

petencies. Journal of theoretical applied information

technology, 70(3):507–515.

ICISSP 2018 - 4th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

232