Sharing With Care

Multidisciplinary Teams and Secure Access to Electronic Health Records

Mohamed Abomhara

1

, Berglind Smaradottir

2

, Geir M. Køien

1

and Martin Gerdes

2

1

Department of Information and Communication Technology, University of Agder, Norway

2

Centre for eHealth, University of Agder, Norway

Keywords:

Multidisciplinary Team, Collaborative Healthcare, Electronic Health Record, Access Control, Security,

Privacy.

Abstract:

Ensuring patient privacy and improving patient care quality are two of the most significant challenges faced

by healthcare systems around the world. This paper describes the importance and challenges of effective mul-

tidisciplinary team treatment and the sharing of patient healthcare records in healthcare delivery. At present,

electronic health records are used to create, manage and share patient healthcare information efficiently and

effectively. The security and privacy concerns with sharing and the proper use of protected health information

need to be highlighted. Additionally, an access control solution is presented, which is suitable for collabora-

tive healthcare systems to address concerns with information sharing and information access. In this access

control model, the multidisciplinary team is classified based on Belbin’s team role theory to ensure that access

rights are adapted dynamically to the actual needs of healthcare professionals and to guarantee confidentiality

as well as protect the privacy of sensitive patient information.

1 INTRODUCTION

Electronic health records (EHRs) and multidisci-

plinary teams (MDTs) have become a vital part of

modern healthcare delivery (Smaradottir et al., 2016b;

O’Daniel and Rosenstein, 2008; Firth-Cozens, 2001).

Daily clinical care necessitates the collaborative sup-

port of MDTs including healthcare professionals

(physicians, specialists, and nurses) and healthcare

organizations (clinics and hospitals) (Abomhara and

Køien, 2016). Such MDT treatment within or among

healthcare organizations has been shown to have im-

mediate and positive impact on patient care (Jnr,

2011; Kim et al., 2010). Moreover, EHRs are widely

adopted by healthcare providers and patients to cre-

ate, manage and share patient healthcare informa-

tion efficiently and effectively (Chao, 2016). The

barrier that currently overshadows the effective use

of EHRs is the lack of security control over infor-

mation flow, whereby protected health information

is shared among a group of people within or across

healthcare organizations (Abomhara and Yang, 2016;

Fern

´

andez-Alem

´

an et al., 2013). A major concern is

to avoid unauthorized disclosure and improper access

to patient healthcare records. Patient records contain

sensitive information, which calls for the enhance-

ment and development of existing security mecha-

nisms (particularly access control) to ensure secure

sharing of health information (Vodicka et al., 2013;

Alhaqbani and Fidge, 2008).

In this study, an investigation is conducted on the

collaboration requirements, patient data confidential-

ity and the need for flexible access of the MDTs cor-

responding to the requirements to fulfill their duties

(section 2), followed by an overview of the existing

access control models (section 3). Section 4 demon-

strates how the proposed work-based access control

model (WBAC) (described earlier by (Abomhara and

Køien, 2016; Abomhara and Yang, 2016; Abomhara

and Nergaard, 2016; Abomhara et al., 2017)) is suit-

able for supporting MDT treatment of information

sharing and information security. Discussion and crit-

ical observations are presented in section 5. Section 6

concludes the study.

2 BACKGROUND

This section provides a background of MDTs care,

EHRs and healthcare record security.

Abomhara, M., Smaradottir, B., Køien, G. and Gerdes, M.

Sharing With Care - Multidisciplinary Teams and Secure Access to Electronic Health Records.

DOI: 10.5220/0006562403790386

In Proceedings of the 11th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2018) - Volume 5: HEALTHINF, pages 379-386

ISBN: 978-989-758-281-3

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

379

Resource

1

Resource

2

Resource

3

Alex

Dean

Cara

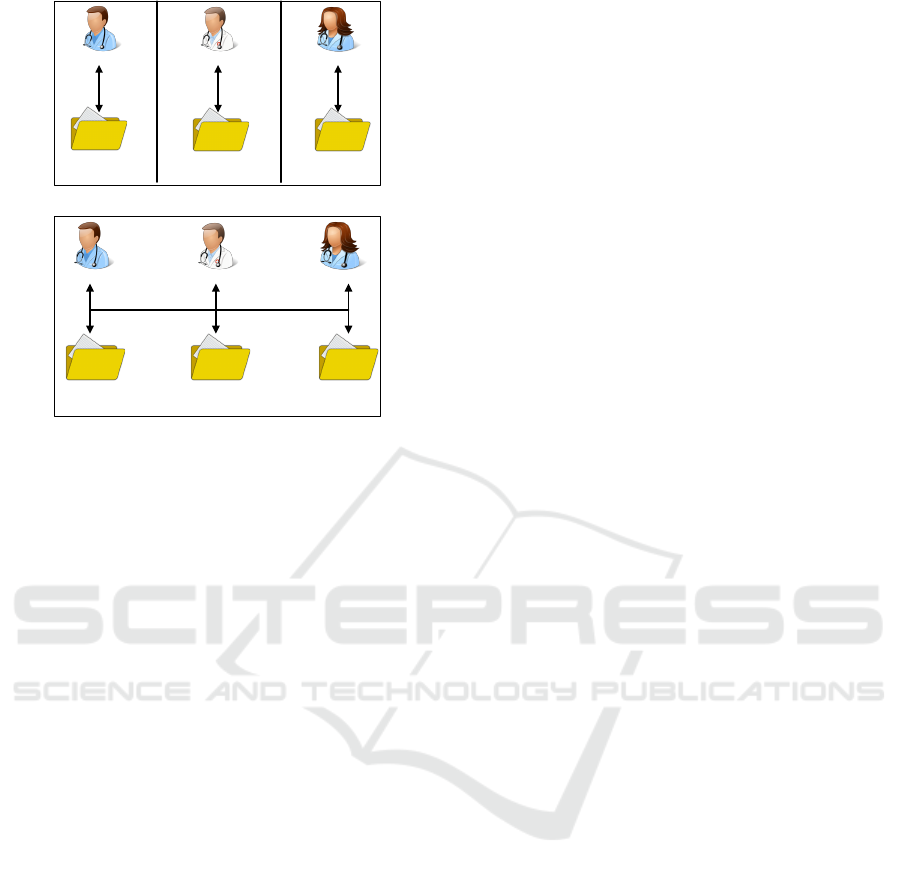

(a) Resource in isolation

Resource

1

Resource

2

Resource

3

Alex

Dean

Cara

(b) Resource sharing in collaborative environ-

ment

Figure 1: Resource in isolation and resource sharing

(Abomhara and Yang, 2016).

2.1 Multidisciplinary Team Care

A MDT is defined as a group of healthcare profession-

als from different disciplines, who ideally possess a

variety of skills necessary to provide specific patient

services with the aim of delivering effective patient

care (Jnr, 2011; Firth-Cozens, 2001) and improving

the outcomes of patients with complex chronic dis-

eases (Monteleone et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2010).

The importance and the effectiveness of MDT have

been particularly highlighted in many studies (Jnr,

2011; Kim et al., 2010). A typical example of patient

care involving MDT is a pregnant woman (Amy) with

diabetes who develops a pulmonary embolism (PE)

(Monteleone et al., 2016). Her medical care team

could include (but is not limited to) an obstetrician, an

endocrinologist, a respiratory physician, nurses and

others.

One of the key aspects of an MDT is resource

sharing (Fabian et al., 2015). To cooperate, each team

member must be prepared to gather and share their

findings with the other team members. In order to an-

alyze, decide and solve a certain patient case collabo-

ratively, the team members must have similar knowl-

edge of the actual situation. According to Figure 1,

each healthcare professional initially accesses their

own resource in isolation (Fig. 1(a)). However, upon

establishing the MDT treatment, the process of shar-

ing progresses (Figure 1(b)).

Although MDT treatment generally improves pa-

tient outcome, there are a number of challenges and

barriers to the success of the MDT. These chal-

lenges can be insufficient organization and resource

management, poor coordination and communication

(O’Daniel and Rosenstein, 2008; Firth-Cozens, 2001)

as well as health records security and privacy vi-

olation (Fern

´

andez-Alem

´

an et al., 2013; Coorevits

et al., 2013). If the effort in an MDT is not prop-

erly managed and organized, productivity may suf-

fer. Good coordination and communication skills are

at the core of patient safety and effective teamwork.

When healthcare providers engage in an MDT activ-

ity, they are required to switch between varying tasks

and roles of distinct nature. It implies that the MDT

environment must include a systems such as EHRs

that assist with task switching accordingly, allows

good resource communication between the MDT and

the patient, as well as ensures the availability, con-

fidentiality, and integrity of resources by providing

them only to those with proper authorization.

2.2 Electronic Health Records

EHRs are compilations of the various types of health

records of patients and are stored in electronic format.

EHR integration in healthcare organizations (clinics

and hospitals) offers potential benefits in terms of im-

proved care quality (Chao, 2016), simplified manage-

ment and enabling efficient in- and out-patient record

exchange. Thus, costs associated with patient care

and administrative overhead are reduced (Bain, 2015;

Alhaqbani and Fidge, 2008). A significant component

of EHRs is the key role in various aspects of facilitat-

ing the MDT to fulfil the information requirements

of daily clinical care (Chao, 2016). Both healthcare

providers (healthcare professionals and/or organiza-

tions) and patients can benefit from the EHR feature

of health record management and sharing. Patient

records can be created by one healthcare professional

and digitally shared and reviewed by other profession-

als instantly.

EHRs can overcome the traditional barriers to

MDTs by enabling communication between partici-

pants and providing rapid access to healthcare records

when distance separates the participants (Vawdrey

et al., 2011). It improves how the MDTs work and

enables more fluid cooperation and information ex-

change between healthcare professionals within and

among healthcare organizations. To cite an example,

within the EU project United4Health (United4Health,

2017), a collaborative telemedicine system for remote

monitoring of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

(COPD) was developed to support MDT work across

the organization of health care services. Both hospi-

tals and municipal healthcare services have access to

HEALTHINF 2018 - 11th International Conference on Health Informatics

380

patient information (Smaradottir et al., 2016a). In a

related study, a similar system was developed to sup-

port collaborative MDT work in dementia healthcare

(Smaradottir et al., 2016b; Smaradottir et al., 2015).

Although EHR systems may improve healthcare

quality, the digitalization of health records, the col-

lection, evaluation and provisioning of patient data,

and the transmission of health data over public net-

works (the Internet) pose new privacy and security

threats (Abomhara et al., 2015; Rostad et al., 2007).

Such threats include, among others, (1) improper dis-

closure of sensitive healthcare information by privi-

leged healthcare professionals, (2) unauthorized ac-

cess to healthcare information by persons taking ad-

vantage of the MDT environment and (3) cyber crim-

inals gaining access to valuable data such as protected

health information (PHI) (Abomhara et al., 2015).

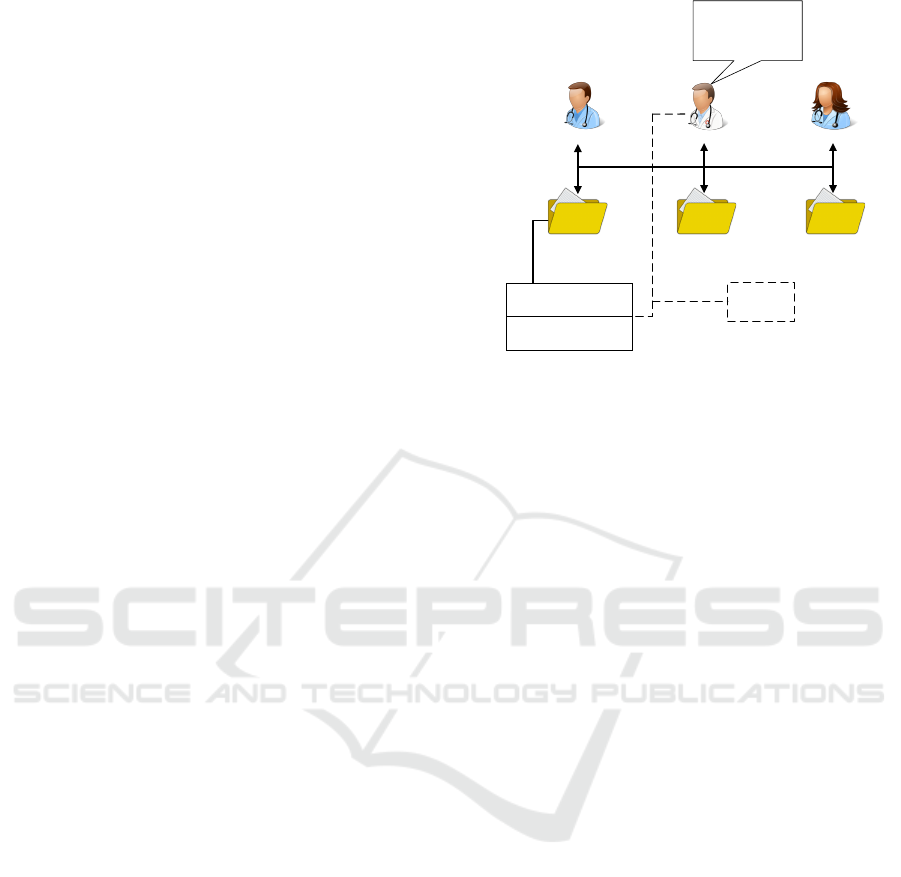

Improper disclosure or unauthorized access may

occur when someone within the MDT accesses shared

resources for unethical reasons (insider threat (Probst

et al., 2010)), for instance accessing a patient’s private

information for personal gain. One of the main causes

of an improper disclosure is information leakage,

which emerges when a supporting party is granted ac-

cess beyond what is actually required. In Figure 2, it

is assumed that three physicians are working collab-

oratively on a pregnant woman example (section 2.1)

at the hospital. They are discussing the possible treat-

ment for a patient. To do so, they must analyze her

medical file but not her personal information. How-

ever, the 2

nd

physician (Alex) is curious about the pa-

tient. He exploits the collaborative environment to ob-

tain more personal information without permission.

2.3 Security and Privacy of EHRs

Security and privacy have been a major con-

cern for patient and healthcare providers world-

wide (Fern

´

andez-Alem

´

an et al., 2013; Liu et al.,

2011). These concerns have limited the international

adoption of EHRs and their uptake by healthcare

providers. Vodicka et al. (2013) carried out a sur-

vey on considering online access to patient records

and found that approximately one-third of partici-

pants had concerns about the security and privacy

of their health records. Moreover, according to “the

2017 cost of a data breach study: global overview”

report (survey done by IBM and Ponemon Institute

(Snell, 2017)), a report on “improving cybersecurity

in the healthcare industry” (US Department of Health

and Human Services et al., 2017), and a report entitled

“hacking healthcare IT in 2016 lessons the healthcare

industry can learn from the opm breach” (Institute

for critical infrastructure technology, 2016), health-

Resource

1

Resource

2

Resource

3

Amy personal

information

Contact number,

Address, Marital status

Amy personal

information

Contact number,

Address, Marital status

Amy is attractive!

I can get more

information about

her easily.

Unethical

access

Alex

Dean

Cara

Figure 2: Insider threat.

care data breach costs are the second highest category

in comparison. Breaches include stealing protected

health information for later use to launch numerous

fraud attacks on related medical parties. Thus, the

findings of these studies demonstrate that the security

and privacy concerns regarding EHRs need to be ad-

dressed before EHRs can be fully accepted by patients

and health providers.

The “Health Insurance Portability and Account-

ability Act” (HIPAA) (Nosowsky and Giordano,

2006) and “code of conduct for information secu-

rity” (Norwegian Directorate of eHealth, 2017) are

examples for legislation to protect the privacy of pa-

tients’ medical records as well as ensure the way

health information is used, disclosed and maintained

by healthcare organizations and healthcare profes-

sionals. They provided a list of security and privacy

suggestions and legal requirements to address the

need to protect healthcare information. As a means

of overcoming authorization and improper access is-

sues associated with EHRs, access control models

such as role-based access control (RBAC) (Ferraiolo

et al., 2001), attribute-based access control (ABAC)

(Hu et al., 2014) and others (Tolone et al., 2005) may

prove to be the answers.

3 ACCESS CONTROL MODELS

Access control is the most popular approach for de-

veloping an active form of mitigating authorization

threats (Rubio-Medrano et al., 2013; Tolone et al.,

2005). The most challenging concern with deploy-

ing access control in a collaborative healthcare en-

vironment is deciding on the extent and limit of in-

formation sharing. For instance, if the main physi-

Sharing With Care - Multidisciplinary Teams and Secure Access to Electronic Health Records

381

cian is treating a patient with sensitive data, the ques-

tion is which data should be disclosed to an assist-

ing practitioner so that collaboration can be effective,

and which should be hidden to safeguard the patient’s

privacy (Fern

´

andez-Alem

´

an et al., 2013). According

to our survey and others’ (Fern

´

andez-Alem

´

an et al.,

2013), it appears that, RBAC is a popular model for

access control and it widely employed in medical in-

dustry (Rostad et al., 2007). RBAC provides security

by utilizing the role of a person in a particular organi-

zation. However, it is quite difficult to define access

when considering other relevant aspects beyond the

one specified by role (e.g., time and location). This

was one of the motivations for developing ABAC (Hu

et al., 2014). The result of using RBAC is not quite

satisfactory. The main reason is that, among others,

RBAC are not well-suited with EHRs to handling un-

planned and dynamic events (e.g., when healthcare

provider asked for second opinions from other health-

care provider) (Fern

´

andez-Alem

´

an et al., 2013; Ros-

tad et al., 2007).

It can be concluded that current access control

models in most previous studies do not support poli-

cies for collaborative MDT environments. This lim-

its these methods to single access to the resources

in centralized environments. Thus, extended fine-

grained components need to be developed for collabo-

rative healthcare MDT environments (Abomhara and

Køien, 2016).

4 SECURE SHARING OF EHRs

To combine the strengths of both RBAC and ABAC

approaches without being hindered by their limita-

tions, work-based access control (WBAC) has been

proposed by introducing the team role (section 4.1)

concept and modifying the team user-role assignment

model from RBAC and ABAC (Abomhara et al.,

2017; Abomhara and Køien, 2016; Abomhara and

Yang, 2016). WBAC enforces a three-layer access

control that applies RBAC, a secondary RBAC and

ABAC. The secondary RBAC layer, with extra roles

extracted from the MDT work requirements, is added

to manage the complexity of cooperative engage-

ments in the healthcare domain. Policies related to

collaboration and MDT’s work are encapsulated in

this coordination layer to ensure that the RBAC layer

and ABAC layer are not overly burdened. The WBAC

model is defined in terms of individuals being as-

signed to roles or teams, team members being as-

signed to team roles, work being assigned to teams

and permissions being associated with roles and team

roles. Role and team role are used in conjunction with

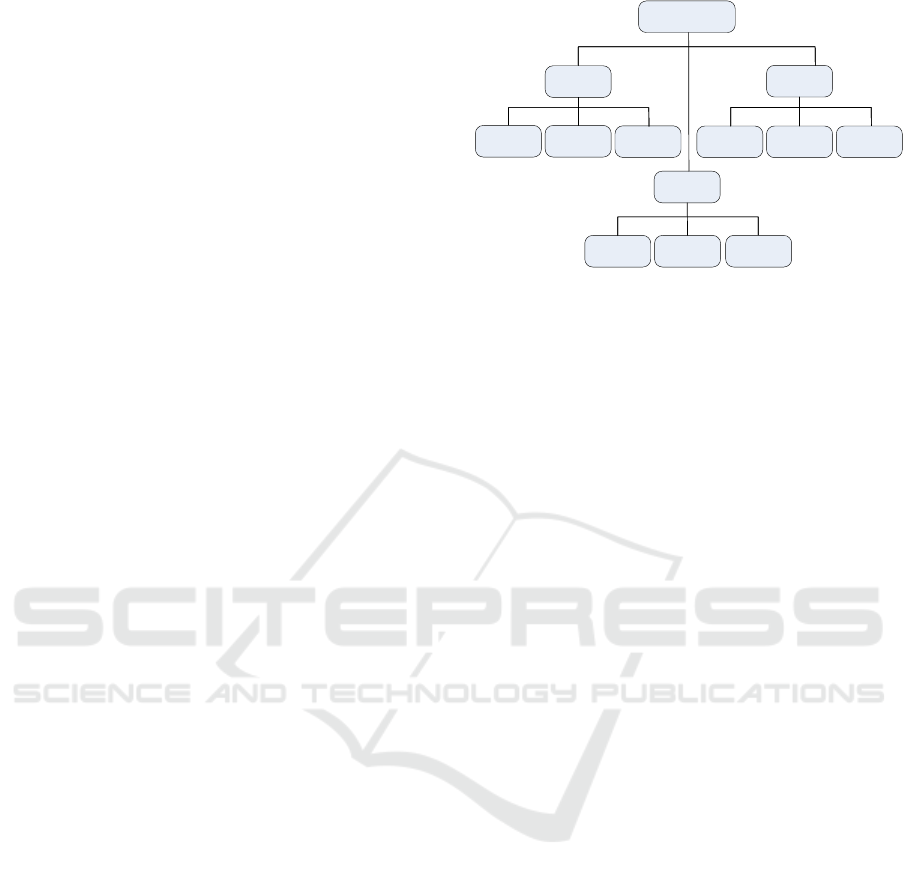

Role

Management

Action

Thought

Coordinator

Networker

Doer Motivator

Thinker Evaluator

Mediator

Mentor

Checker

Figure 3: Taxonomy of team role (Abomhara and Køien,

2016).

dealing with access control in dynamic collaborative

environments.

4.1 Team Role Classification

Hospital personnel roles are often simplistically split

into medical practitioners, nurses and administrators,

to name a few. However, their roles in an MDT can

be further categorized using the team role theory (so-

called also Belbin’s team roles) (Belbin, 2012; Bel-

bin, 2010).

The effectiveness of MDTs is limited unless they

have a clear role and position in organizational struc-

ture of the service. Belbin’s team role theory is

very useful for higher level team building processes,

as it helps an experienced facilitator identify pat-

terns that exist within any team and thus underpin

their strengths and weaknesses. In previous works

(Abomhara et al., 2017; Abomhara and Køien, 2016;

Abomhara and Yang, 2016), the MDT was segregated

into thought, action and management (Figure 3)

based on contributions to the MDT work.

• Thought denotes a role that is dominated mostly

in thinking, analyzing problems and/or providing

technical expertise. To be a successful thought

collaborator, the person may need to understand

the medical predicament in detail without neces-

sarily knowing the patient. A worker in this role

could be involved in devising strategies to con-

front particular medical enigmas. Thus, a cardi-

ology specialist may offer his expertise regarding

the best practices of performing a heart transplant

on a child without being involved in the actual op-

eration.

• The action role pertains to team leaders (e.g., pri-

mary doctor) and members who are involved in

the direct care of the patient, such as meeting

the patient for a medical checkup. These team

members like physicians and nurses are generally

HEALTHINF 2018 - 11th International Conference on Health Informatics

382

based where the patient receives treatment. Hav-

ing an action role usually implies close interaction

with the patient. Nevertheless, discretion is still

feasible with care.

• The management category comprises personnel

who are mostly involved in managing others (e.g.,

guide, listen, delegate, and solve conflicts). These

types of collaborators are adept at coordinating

teamwork. For example, in conflict management,

they may have to resolve series of opposing di-

agnoses made by medical practitioners that may

otherwise escalate into serious altercations. In

this regard, such personnel’s need for information

is inwardly oriented. They have a greater need

to know personal information about other team

members rather than about patients.

4.2 Resource Classification

Medical record classification requires a great deal of

effort and skills to accomplish. This is due to prob-

lems like, for one, medical records containing a wide

range of information (Thomas, 2009), not all of which

may be shareable (Asif et al., 2007). It may include

personal names, phone numbers, addresses, appoint-

ment schedules, to do lists, as well as medical history

and surgical history records, to name a few. Some

elements of this information may be confidential and

sensitive, while others may be open for access. In

an environment that supports resource sharing (Fig-

ure 1(b)), unwanted parties could retrieve confiden-

tial information (Figure 2), thus causing information

leakage and leading to the violation of patient privacy.

Second, healthcare providers cannot decide on what

appropriate information is really necessary in a pa-

tient’s treatment case.

In general, information sharing is required for

treatment; therefore, healthcare providers may use

and disclose patient records on the patient’s treatment

without that patient’s authorization. This may occur

during consultation between healthcare providers re-

garding a patient or patient referral by one provider

to another. However, in most cases when health-

care providers are dealing with sensitive informa-

tion regarding the patient, patient authorization is re-

quired for disclosure, for instance, the disclosure of

psychotherapy notes. According to HIPAA Privacy

Rule (US Department of Health and Human Services

et al., 2014), psychotherapy notes are treated differ-

ently from other mental health information. This is

because they contain particularly sensitive informa-

tion and they are the therapist’s personal notes, which

are not typically required or useful for treatment or

healthcare operation purposes, other than by the men-

tal health professional who created the notes.

It can be said that the amount of information

healthcare providers need to complete their tasks may

vary greatly. The number of medical records a health-

care provider needs to access over a certain period of

time depends on many factors, including the number

of patients they serve, the case they are working on,

and so on. Moreover, such factors vary among health-

care providers and may change from time to time. It

is thus very hard to determine how much risk should

be tolerated for a healthcare provider, if the healthcare

provider believes that knowing more information that

is relevant to their patients conditions enables them to

make better decisions (Rostad et al., 2007).

A realistic way of handling collaboration risks

is to minimize the discrepancy between granted and

required access based on the “minimum necessary”

standard to use and disclose records for treatment

(Agris, 2014). Thus, resources within WBAC are

mainly divided into two types: protected and pri-

vate resources. Protected resources can be shared

within an MDTs work. This depends on whether

the collaborative work needs access to the protected

resources. Contrary to the former type, private re-

sources are highly classified pieces of information in

medical records that would be shared during the MDT

work only if needed. As such, the spreading of ac-

cess control on the basis of collaboration will not af-

fect private resources. It is meant to safeguard cer-

tain confidential information from being leaked out

accidentally through collaborative means. Consider

the example of patient Amy given in section 2.1, in

WBAC model, it was assumed that personal informa-

tion (e.g. name, phone number, address, and/or ID,

etc) and any medical records unrelated to the current

medical case are private resources. In this case, only

the main practitioner (e.g., primary doctor) should be

aware of the patient’s personal information. The other

medical practitioners with supporting roles are given

only information essential for diagnosis (protected re-

source) based on their contributing roles.

4.3 Flow Model of WBAC

The WBAC model utilizes role, team role and WBAC

policies to perform an access control evaluation pro-

cess. First, it checks the access request to verify

whether the requesting user (healthcare provider) pos-

sesses a valid role specified in the system (first RBAC

layer). If the requesting user holds the right role,

WBAC will check the permission associated with

the role and then inspect the rule(s) within the main

WBAC policies for additional constraints (ABAC

layer) on access. In other models such as RBAC, fail-

Sharing With Care - Multidisciplinary Teams and Secure Access to Electronic Health Records

383

ure in this stage results in the complete termination of

the decision process. WBAC, however, treats this dif-

ferently. If the requesting user does not hold a valid

role (in most cases, the requesting user might be an

outsider who is invited to collaborative work and does

not hold a role in the organization), WBAC investi-

gates further to determine whether the requesting user

is part of the collaborative work (a secondary RBAC

layer). If so, the respective user’s team role is ex-

tracted and examined for whether the requesting user

possesses a valid team role over the resource. WBAC

also checks the permission associated with the team

role and checks the rule(s) within WBAC collabora-

tive policies for additional constraints (ABAC layer)

on access.

According to the security and performance analy-

sis of the proposed model (Abomhara et al., 2017),

WBAC is suitable for collaborative healthcare sys-

tems in addressing information sharing and informa-

tion security matters. It caters to the requirements of

access control in collaborative environments and pro-

vides a flexible access control model without compro-

mising the granularity of access rights. Moreover, this

model is secure and easy to manage for supporting co-

operative engagements that are best accomplished by

organized, dynamic teams of healthcare practitioners

within or among healthcare organizations whose ob-

jective is to achieve a specific work (patient treatment

case).

5 DISCUSSION AND

OBSERVATIONS

MDTs are likely to benefit everyone, but for such

teams to keep working well, skills and sufficient coor-

dination as well as resource management are needed.

EHRs can improve the work within MDTs, through

which medical providers share healthcare informa-

tion more easily and work together as a team to solve

particular medical cases. However, the EHRs might

also leave patients more susceptible to privacy viola-

tion where confidential information is improperly ac-

cessed and exploited by MDT members. It is chal-

lenging to predefine all access needs for MDTs based

on the subject-object model. One example of such

a situation is explained in our example (section 2.1),

which may not be predictable and it would be hard

to express the condition of who should join the MDT.

Moreover, in deciding on the extent and limit of re-

source sharing, for instance, in the case of Amy’s treat-

ment (section 2.1), which sensitive data should be dis-

closed to an assisting practitioner so collaboration can

be effective, and which should be hidden to safeguard

the patient’s privacy?

There are certain observations that we have

learned from the previous studies that should be con-

sidered before we could decide on the security model.

Observations as follows:

1. What do patients and healthcare providers

want from EHRs? From the patient perspec-

tive, patients found EHRs are useful and accept-

able. The majority were concerned about security

and confidentiality, including access and disclo-

sure of their records. It’s clear that, on the one

hand, patients want EHR systems to make health

data accessible, available and easy for healthcare

provider to find and use. However, on the other

hand, they also want to be informed regarding

access, disclosure and use of their data. From

the perspective of healthcare providers, they want

EHRs to make their practice work better, easy to

manage and be able to coordinate patient care eas-

ily by communicating with one another, deciding

who will be doing what interventions and then

sharing the information across all of them in a way

that EHRs really facilitate (O’Daniel and Rosen-

stein, 2008).

2. What is good for security is not necessary use-

ful for MDT practice? Bridging the gap between

security requirements and MDT practice is a crit-

ical focus for security researchers. This is a chal-

lenge because what is good for security is not al-

ways what healthcare providers want. On the one

hand, healthcare provider (members of MDTs)

need tools such as EHRs to provide, among oth-

ers, an easy sharing of health information, real-

time access to health records and should be easy

to use. On the other hand, security seeks to en-

sure the healthcare records’ availability, confiden-

tiality, and integrity while providing them only

to those with proper access rights. Security re-

searchers, specifically in access control and au-

thorization, have made the best effort to propose

an access control model that balances between se-

curity and MDT requirements. Yet, these models

do not always meet the needs of MDTs due to the

inconsistencies that exist within the MDT work-

flow and these models’ approaches.

3. How do MDTs form and develop? In general,

many studies (Monteleone et al., 2016; Jnr, 2011;

Firth-Cozens, 2001) have discussed the need and

the effectiveness of MDTs in healthcare delivery.

Yet, however, few address the development of the

MDTs in healthcare organization. It would be

worthwhile if studies could also be conducted on

the forming, storming, norming and performing

HEALTHINF 2018 - 11th International Conference on Health Informatics

384

of MDTs similar to other industries (Arrow et al.,

2000).

4. EHRs require better ways to securely exchange

information: EHRs are promising to be an ideal

solution for addressing the information exchange

challenges that today’s MDTs are facing. It pro-

vides an automated and fast information exchange

to healthcare providers within or among health-

care organizations. However, security and privacy

mechanisms to ensure secure interoperable EHR

applications are slowly beginning to emerge. For

access (uses and disclosures) of patient health in-

formation, access control policies and procedures

must be in place to identify and authorize a health-

care provider or MDT member who needs access

to the health information to carry out their job du-

ties, the type of information needed, and condi-

tions appropriate to such access. For example, ac-

cess control policies should permit only doctors,

or other involved in treatment, to have access to

patient medical records, as needed.

5. Legislation and regulation of electronic ex-

change of health information: According to

HIPPA (Nosowsky and Giordano, 2006) and the

code of conduct for information security (Nor-

wegian Directorate of eHealth, 2017), healthcare

providers should inform and obtain a patient’s

permission (e.g., consent or authorization) on how

the patient’s records are used or disclosed. Un-

der the terms of HIPAA (Agris, 2014), a valid au-

thorization to use or disclosure health information

must contain “a description of the information to

be used or disclosed”; “the name of the person or

entity authorized to make the use or disclosure”;

“the name of the person or entity to whom the dis-

closure may be made”; “a description of each pur-

pose of the requested use or disclosure”; “an expi-

ration date or expiration event” and “the signature

of the individual and date”.

As a result of this, it could be concluded that, if

we don’t coordinate the MDT and shared information,

we cannot coordinate the patient care, and if we don’t

coordinate the patient care, we will have inefficiency

and poor healthcare quality.

6 CONCLUSIONS

It is evident that EHRs have a great potential to sup-

port MDTs work, including but certainly not limited

to create, manage and share patient healthcare infor-

mation as well as facilitate an easy coordination and

communication between healthcare providers, thus

improving patient satisfaction and engagement. How-

ever, unauthorized disclosure and improper access

to patient healthcare records are a major concern of

this study, where sensitive healthcare data is shared

among a group of healthcare professionals within or

across organizations.

WBAC was proposed to address these concerns

and support the security and MDT requirements on

access control. The major contributions of the WBAC

model include ensuring that access rights are dy-

namically adapted to the actual needs of health-

care providers, and providing fine-grained control

of access rights with the least privilege principle,

whereby healthcare providers are granted minimal ac-

cess rights to carry out their duties.

REFERENCES

Abomhara, M., Gerdes, M., and Køien, G. M. (2015).

A stride-based threat model for telehealth systems.

Norsk informasjonssikkerhetskonferanse (NISK),

8(1):82–96.

Abomhara, M. and Køien, G. M. (2016). Towards an access

control model for collaborative healthcare systems.

In HEALTHINF’16, 9th International Conference on

Health Informatics, volume 5, pages 213–222.

Abomhara, M. and Nergaard, H. (2016). Modeling of work-

based access control for cooperative healthcare sys-

tems with xacml. In Proceedings of the Fifth in-

ternational conference on global health challenges

(GLOBAL HEALTH 2016), pages 14–21.

Abomhara, M. and Yang, H. (2016). Collaborative and

secure sharing of healthcare records using attribute-

based authenticated access. International Journal on

Advances in Security Volume 9, Number 3 & 4, 2016.

Abomhara, M., Yang, H., Køien, G. M., and Lazreg, M. B.

(2017). Work-based access control model for coop-

erative healthcare environments: Formal specification

and verification. Journal of Healthcare Informatics

Research, pages 1–33.

Agris, J. L. (2014). Extending the minimum necessary

standard to uses and disclosures for treatment: Cur-

rents in contemporary bioethics. The Journal of Law,

Medicine & Ethics, 42(2):263–267.

Alhaqbani, B. and Fidge, C. (2008). Access control re-

quirements for processing electronic health records.

In Business Process Management Workshops, pages

371–382. Springer.

Arrow, H., McGrath, J. E., and Berdahl, J. L. (2000). Small

groups as complex systems: Formation, coordination,

development, and adaptation. Sage Publications.

Asif, K., Ahamed, S. I., and Talukder, N. (2007). Avoiding

privacy violation for resource sharing in ad hoc net-

works of pervasive computing environment. In Com-

puter Software and Applications Conference, 2007.

COMPSAC 2007. 31st Annual International, vol-

ume 2, pages 269–274. IEEE.

Sharing With Care - Multidisciplinary Teams and Secure Access to Electronic Health Records

385

Bain, C. (2015). The implementation of the electronic med-

ical records system in health care facilities. volume 3,

pages 4629–4634. Elsevier.

Belbin, R. M. (2010). Management teams: Why they suc-

ceed or fail. Human Resource Management Interna-

tional Digest, 19(3).

Belbin, R. M. (2012). Team roles at work. Routledge.

Chao, C.-A. (2016). The impact of electronic health records

on collaborative work routines: A narrative network

analysis. International journal of medical informatics,

94:100–111.

Coorevits, P., Sundgren, M., Klein, G. O., Bahr, A., Claer-

hout, B., Daniel, C., Dugas, M., Dupont, D., Schmidt,

A., Singleton, P., et al. (2013). Electronic health

records: new opportunities for clinical research. Jour-

nal of internal medicine, 274(6):547–560.

Fabian, B., Ermakova, T., and Junghanns, P. (2015). Collab-

orative and secure sharing of healthcare data in multi-

clouds. Information Systems, 48:132–150.

Fern

´

andez-Alem

´

an, J. L., Se

˜

nor, I. C., Lozoya, P.

´

A. O., and

Toval, A. (2013). Security and privacy in electronic

health records: A systematic literature review. Journal

of biomedical informatics, 46(3):541–562.

Ferraiolo, D. F., Sandhu, R., Gavrila, S., Kuhn, D. R., and

Chandramouli, R. (2001). Proposed nist standard for

role-based access control. ACM Transactions on In-

formation and System Security (TISSEC), 4(3):224–

274.

Firth-Cozens, J. (2001). Multidisciplinary teamwork: the

good, bad, and everything in between.

Hu, V. C., Ferraiolo, D., Kuhn, R., Schnitzer, A., Sandlin,

K., Miller, R., and Scarfone, K. (2014). Guide to at-

tribute based access control (abac) definition and con-

siderations. NIST Special Publication, 800:162.

Institute for critical infrastructure technology (2016). Hack-

ing healthcare it in 2016 lessons the healthcare indus-

try can learn from the opm breach. Institute for critical

infrastructure technology.

Jnr, G. O. A. (2011). The effect of multidisciplinary team

care on cancer management. Pan African Medical

Journal, 9(1).

Kim, M. M., Barnato, A. E., Angus, D. C., Fleisher, L. F.,

and Kahn, J. M. (2010). The effect of multidisci-

plinary care teams on intensive care unit mortality.

Archives of internal medicine, 170(4):369–376.

Liu, L. S., Shih, P. C., and Hayes, G. R. (2011). Barriers

to the adoption and use of personal health record sys-

tems. In Proceedings of the 2011 iConference, pages

363–370. ACM.

Monteleone, P. P., Rosenfield, K., and Rosovsky, R. P.

(2016). Multidisciplinary pulmonary embolism re-

sponse teams and systems. volume 6, page 662. AME

Publications.

Norwegian Directorate of eHealth (2017). Code of conduct

for information security the healthcare and care ser-

vices sector.

Nosowsky, R. and Giordano, T. J. (2006). The health insur-

ance portability and accountability act of 1996 (hipaa)

privacy rule: implications for clinical research. Annu.

Rev. Med., 57:575–590.

O’Daniel, M. and Rosenstein, A. H. (2008). Professional

communication and team collaboration.

Probst, C. W., Hunker, J., Gollmann, D., and Bishop, M.

(2010). Insider Threats in Cyber Security, volume 49.

Springer Science & Business Media.

Rostad, L., Nytro, O., Tondel, I., and Meland, P. H. (2007).

Access control and integration of health care systems:

An experience report and future challenges. In Avail-

ability, Reliability and Security, 2007. ARES 2007.

The Second International Conference on, pages 871–

878. IEEE.

Rubio-Medrano, C. E., D’Souza, C., and Ahn, G.-J. (2013).

Supporting secure collaborations with attribute-based

access control. In Collaborative Computing: Net-

working, Applications and Worksharing (Collaborate-

com), 2013 9th International Conference Conference

on, pages 525–530. IEEE.

Smaradottir, B., Gerdes, M., Martinez, S., and Fensli, R.

(2016a). The eu-project united4health: User-centred

design of an information system for a norwegian

telemedicine service. Journal of telemedicine and

telecare, 22(7):422–429.

Smaradottir, B., Martinez, S., Holen-Rabbersvik, E.,

Vatnøy, T. K., and Fensli, R. W. (2016b). Usabil-

ity evaluation of a collaborative health information

system. lessons from a user-centred design process.

In HEALTHINF’16, 9th International Conference on

Health Informatics, volume 5, pages 306–313.

Smaradottir, B. F., Martinez, S., Holen-Rabbersvik, E., and

Fensli, R. (2015). ehealth-extended care coordina-

tion: Development of a collaborative system for inter-

municipal dementia teams: A research project with a

user-centered design approach. In International Con-

ference on Computational Science and Computational

Intelligence (CSCI2015), pages 749–753. IEEE.

Snell, E. (2017). Healthcare data breach costs highest for

7th straight year. HealthITSecurity.com.

Thomas, J. (2009). Medical records and issues in negli-

gence. Indian journal of urology: IJU: journal of the

Urological Society of India, 25(3):384.

Tolone, W., Ahn, G.-J., Pai, T., and Hong, S.-P. (2005). Ac-

cess control in collaborative systems. ACM Comput-

ing Surveys (CSUR), 37(1):29–41.

United4Health (2017). European commission competitive-

ness innovation programme.

US Department of Health and Human Services et al. (2014).

Hipaa privacy rule and sharing information related to

mental health.

US Department of Health and Human Services et al. (2017).

Health care industry cybersecurity task force.

Vawdrey, D. K., Wilcox, L. G., Collins, S., Feiner, S.,

Mamykina, O., Stein, D. M., Bakken, S., Fred, M. R.,

Stetson, P. D., et al. (2011). Awareness of the care

team in electronic health records. Appl Clin Inform,

2(4):395–405.

Vodicka, E., Mejilla, R., Leveille, S. G., Ralston, J. D.,

Darer, J. D., Delbanco, T., Walker, J., and Elmore,

J. G. (2013). Online access to doctors’ notes: patient

concerns about privacy. Journal of medical Internet

research, 15(9).

HEALTHINF 2018 - 11th International Conference on Health Informatics

386