Telephone Intervention for Caregivers

Impacts of an Individualized Telephone Intervention Targeting the Caregiver of a

Person with Alzheimer’s with Nonaggressive Behavioural Symptoms

Anne-Sophie Godbout, Jean Vézina and Chantal Dubé

School of Psychology, University Laval, 2325 Allée des Bibliothèques, Québec, Canada

Keywords: Caregiving, Alzheimer’s Disease, Behavioural Symptoms.

Abstract: Caregiving for a person with Alzheimer’s disease can have a negative impact on the individual who has to

endorse this role. High levels of depressive symptoms, anxiety, caregiver burden, and desire to

institutionalize have been reported in the literature. Those consequences justify the development of efficient

interventions that will diminish the individual and societal repercussions of the role of caregiving for a

person with Alzheimer’s disease. The main objective of this study is to evaluate the impacts of a telephone

intervention for caregivers of a person with Alzheimer’s disease. To do so, 50 caregivers were recruited and

randomly assigned to the control group (n = 25) or the intervention group (n = 25). Results show that

caregivers who were assigned to the intervention group showed significant lower levels of depressive

symptoms, anxiety symptoms, caregiver burden and desire to institutionalize. These results support the

pertinence to develop interventions that can help caregivers cope with their role and with the management

of the symptoms of the care receiver.

1 INTRODUCTION

It is now well documented that caregiving for

someone with Alzheimer’s disease can have major

and deleterious impacts on both the mental and

physical health of the person who takes that role

(Alzheimer’s Association, 2017; Liu, & Gallagher-

Thompson, 2009; Vaingankar et al., 2016). High

levels of anxiety, depressive symptoms, caregiver

burden and desire to institutionalize are observed in

this population (Alzheimer’s Association, 2017).

Research has also shown that out of all

categories of symptoms that are observed in

Alzheimer’s disease, behavioural symptoms are

those that have the most negative impacts on the

caregiver’s health (Feast, Moniz-Cook, Stoner,

Charlesworth, & Orrell, 2016; Shiji, George, Price &

Jacob, 2009).

The main objective of this study is to evaluate

the impact on anxiety symptoms, depressive

symptoms, caregiver burden and desire to

institutionalize a telephone intervention for

caregivers of a person with Alzheimer’s disease with

nonaggressive behavioural symptoms.

2 METHODS

2.1 Participants

A total of 50 caregivers of a person with

Alzheimer’s disease were recruited. They were

randomly assigned to either the intervention group

(IG; n = 25) or the control group (CG; n = 25). To be

eligible to participate in this study, the inclusion

criteria for the caregiver were (1) to be the main

caregiver of a person with Alzheimer’s disease for at

least 6 months before the beginning of the study

(2) to have been living with this person for at least 6

months (3) to have a significant level of caregiver

burden (e.g., a score higher than 6 on Zarit’s

caregiver burden scale), (4) not to have frequented

support group in the last 3 months and (5) not to

have auditive problems that are not compensated by

an auditive aid. The inclusion criteria for the person

with Alzheimer’s disease were (1) to have received

the diagnosis at least 6 months before the beginning

of the study, (2) to be at least 50 years old, (3) to be

living at home, (4) to show nonaggressive

behavioural symptoms such has agitation,

wandering, repetitive mannerism on a weekly basis

Godbout, A., Vézina, J. and Dubé, C.

Telephone Intervention for Caregivers.

DOI: 10.5220/0006670500210025

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2018), pages 21-25

ISBN: 978-989-758-299-8

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

21

for at least 4 weeks, and (5) to have obtained a score

on the Dementia Behaviour Disturbance Scale

(DBDS; Baumgarten, Becker & Gauthier, 1990) that

indicates a high level of disturbing behaviour

demonstrations.

2.2 Assessment Measures

A sociodemographic questionnaire was used to get

information on the caregiver’s health state, their

desire to institutionalize the care receiver, their

support system and the services and resources used

were collected. The caregivers also completed the

Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, 1978) to

evaluate caregivers’ depressive symptoms, the Sate-

Trait Anxiety Inventory (ASTA-65+; Bouchard,

Ivers, Gauthier, Pelletier, & Savard, 1998) to

evaluate anxiety symptoms, and Zarit’s Caregiver

Burden Inventory (IFZ; Zarit, Orr, & Zarit, 1985).

The measures used to evaluate the care receiver

were the DBSD (Baumgarten et al., 1990), the

Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS; Hébert, Bravo,

& Girouard, 1992) and the Functional Autonomy

Measurement System (SMAF; Hébert, Carrier &

Bilodeau, 1988).

2.3 Procedure

Participants were recruited with the help of

community organizations. Their contact information

was given to the research team after the caregivers

gave their authorization. Their eligibility was

validated by phone. Each time 4 participants were

eligible, they were randomly assigned to either one

of the experimental situations: the intervention

group (IG) or the control group (CG). Participants

assigned to the CG group were then told that they

were on a waiting list and that they could expect to

receive the treatment in the next 6 months.

A first face-to-face interview between the

caregiver and a member of the research team was

used as the first time of measure. The caregiver was

interviewed for a second time when the treatment

was completed (T1), and three months after (T2).

2.4 Intervention

The treatment consists of 12 individual sessions.

Those are by phone and have a lasting time of

approximately 45 minutes. The program targets the

strategies that the caregiver uses to deal with the

non-aggressive behavioural symptoms of the

disease.

The member of the research team that gave the

treatment was a trained nurse with a degree in

psychology and who had work experience with older

people. She received training during which she was

also given a manual describing the themes and

objectives of each 12 sessions of the treatment

program.

The first sessions were randomly recorded to

ensure the validity of the protocol. Supervision was

given all through the experiment to make sure the

treatment was followed.

The themes covered during the session were the

Alzheimer’s disease (sessions 1 and 2),

consequences of the disease on the caregiver

(session 3), communication with the care receiver

(session 4), the behavioural symptoms of the care

receiver and the possible solutions (sessions 5 to 10),

the available resources that the caregiver could use

(session 11), and the synthesis of the treatment

(session 12).

2.5 Statistical Analysis

The statistical analyzes were made using the SAS-

PC software. First, t-tests were used to describe

the participants’ sociodemographic characteristics

and to compare the two experimentation groups (IG

and CG) on those variables. Since the desire to

institutionalize is a categorical variable, a chi-square

test was performed. Secondly, an analysis of

variance (ANOVA) was used to compare both

groups of caregivers on the measures of depressive

symptoms (BDI), anxiety symptoms (STAI) and

caregiver burden (ZCBI) at T0. ANOVAs were also

used to compare the two care receivers group on the

measure of the frequency and the severity of their

behavioural symptoms (DBDS), their cognitive

functions (3MS) and their functional autonomy

(SMAF).

Finally, the effect of the intervention was

calculated using a multivariate analysis of variance

(MANOVA) with repeated measures. The dependent

variables were the intervention conditions.

Statistically significant results with the MANOVA

were followed by contrast and tendency analysis.

The same procedure was applied to evaluate the

effect of the program on the caregivers' assessment

of the frequency and severity of behavioural

problems of their Alzheimer's relative and the

measurement of their cognitive and functional. The

significance level used for all the tests was a

bilateral alpha threshold of 0.05 alpha.

ICT4AWE 2018 - 4th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

22

3 RESULTS

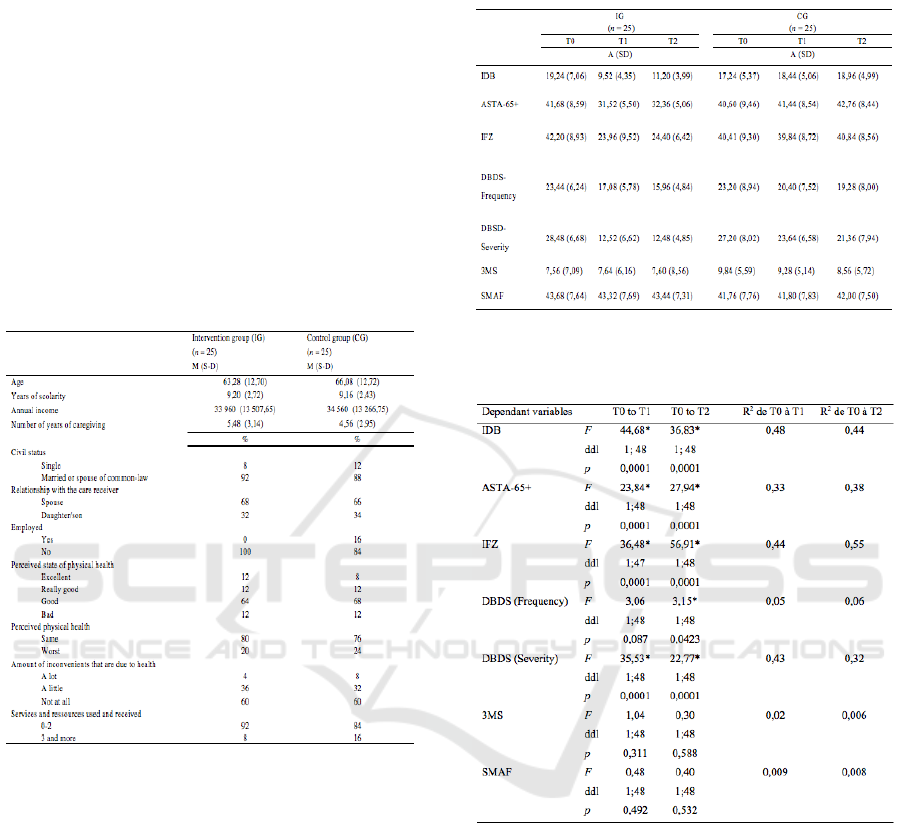

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the

participants on socio-demographic variables (i.e.

health status and services received by the study

group. The final sample consisted of 28 women

(56%) and 22 men (44%). On average, participants

in the study took care of their loved one for about 5

years and the majority of caregivers were the spouse

of the relatives they cared for. Statistical analyzes

revealed that there is no difference between the two

groups on the different descriptive variables.

Table 1: Characteristics of caregivers in the IG and the CG

on socio-demographic variables, health status and services

received.

Table 2 shows the results of the three different

measurement time on the instruments evaluating the

dependent variables for the two experimental

groups. Statistical analyzes revealed that at T0 there

was no significant difference between the two

groups over all the variables measured. At T0,

caregivers in both groups have an average IFZ score

that indicates severe levels of burden.

Table 3 shows the results of the multivariate

analysis that compared the scores of both groups on

the dependent variables. The analysis made it

possible to compare the two groups between T0 and

T1 and between the T0 and the T2. Among the

caregivers, significant differences were between the

two groups with the results at the BDI, the ASTA-65

+ and the IFZ, both between the T0 and the T1 and

between the T0 and the T2.

Table 2: Scores on the dependent variables at each time of

measure.

Table 3: Results of the multivariate analysis comparing the

IG and the CG on the dependent variables.

The caregivers in the IG reported significantly

lower scores on all the instruments evaluating their

condition. As for the care receivers, those assigned

to the IG showed statistically significant lower score

compared to the CG group between T0 and T2 on

the frequency of behavioural disorders. Their scores

had decreased. No difference was observed between

the 2 experimental groups between T0 and T1 on

this variable. The severity of the behavioural

disorders were also significantly lower for the IG

between T0 to T1 and T0 to T2.

The Chi-Square test used to evaluate the desire to

institutionalize indicated a significant difference

between the IG and the CG, 2 (2, n = 25) = 16.96, p

= 0.0002 between T0 and T3. The caregivers

Telephone Intervention for Caregivers

23

assigned to the IG had lower scores than the

caregivers in the CG.

No statistically significant differences were

observed between the measuring times on the

instruments evaluating the cognitive functioning

(3MS) and the functional autonomy of the care

receiver (SMAF).

4 DISCUSSION

Caregiving for a person with Alzheimer's disease has

consequences on different aspects of the caregivers’

psychological and physical health. In fact, caregivers

show higher levels of depressive symptoms, anxiety

symptoms and caregiver burden. Those are linked to

earlier institutionalization of the person they are

caring for. The objective of this study was to

evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention

program in determining whether the caregivers who

received an intervention that helps them manage the

nonagressive behavioural symptoms displayed by

the person they take care of would differentiate from

the caregivers who did not receive the intervention

on measures of depressive symptoms, anxiety,

feeling of burden and desire for institutionalization

of the loved one. The following hypothesizes were

evaluated: caregivers in the IG would show less

depressive symptoms, experience a decrease in their

severity of their anxiety symptoms, have a lower

sense of burden, and would have a decrease in their

desire to institutionalize the person they cared for.

The results show that the importance of the

depressive and anxious symptoms of the caregivers

who received the intervention had decreased in a

tangible way compared to caregivers who have not

benefited from the intervention. In addition, the

perception that the caregiver had of the severity of

the behavioural symptoms of the care receiver

decreased significantly at each measurement time.

The hypothesis that the caregivers who received the

intervention would show a lower sense of burden

than those in the CG was also confirmed. The

caregivers assigned to the IG also expressed a lower

level of desire to institutionalize the care receiver

than the caregivers assigned to the CG. This last

finding could have interesting implications in

reducing the economic and societal costs of

Alzheimer’s disease.

The results of this program seem to indicate that

the intervention has improved the participants’

perceptions of their caregiving skills and increased

their sense of control and capacity to manage the

nonaggressive behavioural symptoms displayed by

their loved one.

It has to be mentioned that even though no

differences were observed on the cognitive and

functional symptoms of the care receiver, the

caregivers assigned to the IG showed decreased

symptoms on all the variables on which they were

evaluated after the treatment program was

completed. As a matter of fact, only the perception

that the caregivers had of the severity and frequency

of the behavioural symptoms were significantly

lower at T3. This finding gives support to the idea

that behavioural symptoms have the most negative

impacts on the caregiver’s health.

Three main elements come out of the results

obtained in this study. First, the program was

individualized, allowing a more personalised and

targeted intervention. Although group interventions

have proven to be an effective treatment option, the

results of this study seem to indicate that

individualized interventions are an interesting and

efficient alternative for caregivers that cannot attend

groups. Therefore, this individualized intervention

could be implemented with caregivers that express

specific needs regarding the behavioural symptoms

of the person they care for.

Secondly, the format of the intervention made it

possible to reach a larger number of caregivers.

Transport issues and busy schedules are important

obstacles to treatment seeking that are often inherent

to caregiving. However, this study provides

evidence that the use of technologies (i.e.:

telephone) are useful tools to give caregivers access

to efficient treatment programs.

Finally, the focus on the behavioural disorders

appears to contribute in great part to the efficacy of

the intervention. As mentioned before, the treatment

specifically targeted the nonaggressive behavioural

symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. The

improvements observed on the different measures

can lead us to believe that interventions addressing

specific symptoms – in this case nonaggressive

behavioural symptoms – can have a positive impact

on the caregiver’s psychological health. In this

sense, the results seem to show that it is important to

address this type of behaviour more systematically

with caregivers, to try to understand the

consequences that they may have on them and to

help them manage these behaviours in order to

improve their psychological health. This finding

could help improve the efficiency of the care

services offered by introducing shorter and targeted

treatment.

ICT4AWE 2018 - 4th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

24

5 CONCLUSIONS

On a daily basis, the caregivers are exposed to the

cognitive, functional and behavioural symptoms of

the care receiver. Since it is well documented that

the behavioural symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease

contribute in high proportions to the negative effects

that caregiving can have on the caregivers’ health,

interventions targeting the management of this

category of symptoms could contribute to

diminishing the social, psychological and economic

cost of this disease. The results of this study give

support to the idea that these types of interventions

could benefit the caregivers.

REFERENCES

Alzheimer’s Association. 2017. Alzheimer’s facts and

figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 13, 325-373.

Baumgarten, M., Becker, R., Gauthier, S. 1990. Validity

and Reliability of the Dementia Behaviour

Disturbance Scale. Journal of the American Geriatrics

Society, 38, 221-226.

Beck, A. T. 1978. Depression Inventory. Philadelphia:

Center for Cognitive Therapy.

Bouchard, S., Ivers, H., Gauthier, J., Pelletier, M.H.,

Savard, J. 1998. Psychometric Properties of the French

Version of the Sate-Trait Inventory (form Y) Adapted

for older people. Canadian Journal on aging, 17, 440-

453.

Feast, A., Moniz-Cook, E., Stoner, C., Charlesworth, G.,

Orrell, M. A. 2016. A systematic review of the

relationship between behavioral and psychological

symptoms (BPSD) and caregiver well-being.

International Psychogeriatrics, 28, 1761-74.

Hébert, R., Bravo, G., & Girouard, D. 1992. Fidélité de la

traduction française de trois instruments d’évaluation

des aidants naturels de malades déments. Canadian

Journal of Aging, 12, 324-337.

Hébert, R., Carrier, R., Bilodeau, A. 1988. Le système de

mesure de l’autonomie fonctionnelle. Revue de

Gériatrie, 13,161-167.

Liu, W., Gallagher-Thompson, D. 2009. Impact of

dementia caregiving: Risks, strains, and growth. In:

Qualls SH, Zarit SH, eds. Aging families and

caregiving. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.;

85-112.

Shiji, K.S., George, R.K., Prince, M.J., Jacob K.S.

2009. Behavioral symptoms and caregiver burden in

dementia. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 45–49.

Vaingankar, J.A., Chong S.A., Abdin, E., Picco, L.,

Shafie, S., Seow E., (...), Subramaniam, M. 2016.

Psychiatric morbidity and its correlates among

informal caregivers of older adults. Comprehensive

Psychiatry, 68, 178-85.

Zarit, S. H., Orr, N. K., Zarit, J. M. 1985. The Hidden

Victims of Alzheimer’s Disease: Families Under

Stress. New York: University Press.

Telephone Intervention for Caregivers

25