Storyboard Interpretation Technology Used for Value-based STEM

Education in Digital Game-based Learning Contexts

Jacqueline Schuldt, Stefan Sachse, Susanne Friedemann and Kati Breitbarth

Human-centered Media Technologies Department, Fraunhofer Institute for Digital Media Technology,

Ehrenbergstraße 31, 98693 Ilmenau, Germany

Keywords:

Digital Game-Based Learning, Game Design, Moral Dilemma Situations, Open Educational Resources,

Storyboarding, Storyboard Interpretation Technology, Usability Engineering, User Experience Design.

Abstract:

Digital games, particularly serious games, are seen as an important element for providing stimulation and

simulation in educational settings. The Storyboard Interpretation Technology (SIT) is a feature to support

the development of games, especially for educational contexts. The Experimento Game is a prototype based

on concepts of SIT. This prototype aims at supporting the development of a students critical reflection in

STEM contexts, taking into account that students must be encouraged to understand the deeper meaning of a

problem. In order to determine the suitability of the digital game, a user experience evaluation with a game test

was carried out for the target group of students at the age of 11 to 13 years. In this paper we firstly outline the

motivation of developing a gaming module called Experimento Game, secondly the theoretical background,

and thirdly the progress of development. Finally we discuss the results of the user experience evaluation by

means of a survey study and the collection of game data using Data Mining.

1 MOTIVATION

Digital games can be understood as moral objects, as

well as mediators of ethical values (Wimmer, 2014).

Game narratives, rulesets, high scores or achieve-

ments suggest righteousness and virtue. Following

this approach, moral dilemmas embedded in digital

games could potentially sensitize gamers in respect

to real-world moral dilemmas and therefore stimulate

critical thinking and ethical reflection (Sicart, 2013;

Krebs, 2013).

In general a Dilemma is defined a situation with

serveral decision-making possibilities. Every possi-

bility is neither wrong nor right. Which choice you

ultimately make has a lot to do with morality but also

with emotional distance (Avram et al., 2014).

How people make decisions in such difficult situ-

ations for themselves and others depends mainly on

three factors: the consequences of their own actions,

both intended and unintended (Avram, 2014). It also

depends on whether you have to intervene actively, or

only to allow you to do what is happening anyway

(Greene et al., 2009). And it depends on which so-

cially defined perceptions there are about which one

is morally bound - and what is taboo (Haidt, 2001). A

weak moral dilemma is a dilemma in which the moral

failure, in contrast to the lack of clarity and urgency

of the decision, plays no great role (Sellmaier, 2008).

The article outlines the peculiarities of moral

dilemmas in STEM contexts in Digital Game-Based

Learning (DGBL) scenarios. The so-called Story-

board Interpretation Technology (SIT), which is ap-

plied in the current game design of Experimento

Game, is the underlying technological approach pub-

lished for the first time in (Fujima et al., 2013) and

(Arnold et al., 2013a).

The Experimento Game is part of Experimento,

the international educational program of the Siemens

Stiftung (Siemens Stiftung, 2017b). The program Ex-

perimento is based on the principle of research-based

learning and offers teacher trainings and curriculum-

oriented hands-on experiments from the fields of en-

ergy, environment, and health. With Experimento, the

Siemens Stiftung also aims to strengthen the teach-

ing and formation of values during science and tech-

nology lessons. All Experimento teaching materials

and additional media are available as Open Educa-

tional Resources (OER) on the media portal of the

Siemens Stiftung. The online portal helps teachers to

find age-appropriate media to introduce their students

to global challenges such as renewable energies, the

greenhouse effect, or the production of clean water.

78

Schuldt, J., Sachse, S., Friedemann, S. and Breitbarth, K.

Storyboard Interpretation Technology Used for Value-based STEM Education in Digital Game-based Learning Contexts.

DOI: 10.5220/0006670700780088

In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2018), pages 78-88

ISBN: 978-989-758-291-2

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

To strengthen the foundation of values during ex-

perimentation, the Siemens Stiftung takes a new path:

the development of a gaming module, which is based

on the principle of learning through discovery. That

implies that children and young people actively shape

their individual learning processes while playing, dis-

covering and understanding scientific and technolog-

ical interrelationships through moral dilemma situa-

tions implemented in a digital game.

Figure 1: Title screen of the Experimento Game.

2 THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Open Educational Resources (OERs) are becoming

increasingly popular in Germany as well as other

countries. The Paris Declaration issued by UNESCO

in 2012 defines these resources as freely accessible

material that may be altered and adapted as needed

(United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural

Organization, 2012). These are educational materials

which are accessible under so-called open licenses.

As a result, OERs open the way for children in the

world’s more destitute regions to have access to edu-

cational resources. Special potential is offered by the

cooperative development and enhancement of these

resources as well as in the simple modification and

distribution thereof.

OERs can be modified and customized in a

legally compliant manner, thereby fulfilling impor-

tant requirements for locally differentiated, but inclu-

sive instruction in increasingly heterogeneous school

classes. For students, the active use of educational

resources promotes self-determined learning, in ad-

dition to an understanding of the internet and media.

In broad terms, OERs support a creative working re-

lationship between teachers and students, and facili-

tate new collaborative forms of teaching and learning.

(Siemens Stiftung, 2017b)

2.1 STEM and Values: How Values Can

Be Taught in Schools

There is big potential in combining STEM educa-

tion (science, technology, engineering and mathemat-

ics) and values together, not only for individuals but

at the same time for further developing society at

large. Currently there are just a few teaching meth-

ods, which promote technical knowledge and at the

same time strengthen students ability to form values.

Experimento Game, a digital game, tackles this ap-

proach.

2.1.1 Digital Game-Based Learning (DGBL)

Definitions of Digital Game-Based Learning ordinar-

ily emphasize that it is a type of game play with de-

fined learning outcomes (Plass et al., 2016).

Digital Games are a complex genre of learning en-

vironments that cannot be understood by taking only

one perspective of learning. Numerous of the con-

cepts, such as motivation, include aspects relating

to different theoretical foundations: cognitive, affec-

tive, motivational, and sociocultural; which are im-

portant in the context of game design and game re-

search (Plass et al., 2016).

Plass et al. (2016) argue that all these perspectives

have to be taken into account, with specific emphases

depending upon the intention and design of the learn-

ing game, to achieve their potential for playful learn-

ing.

2.1.2 Experimento Game: A New Path of

Experimento

Experimento, the international educational program

of the Siemens Stiftung, has been developed by edu-

cationalists for use in preschools, elementary schools,

and secondary schools. It offers teachers and educa-

tors a practical and curriculum-oriented selection of

topics in the areas of energy, health, and environment.

Some 130 experiments developed for age groups 4-

7 (Experimento|4+), 8-12 (Experimento|8+) and 10-

18 (Experimento|10+) ensure that children and young

people gain knowledge they can use throughout the

educational chain. They can explore, reflect upon

and understand scientific and technological subjects

independently and further develop their knowledge of

global challenges in a way that is appropriate to their

age group. (Siemens Stiftung, 2017a)

The Siemens Stiftung is going to expand their

offer with the gaming module called Experimento

Game, developed by Fraunhofer IDMT.

The Experimento Game is an adventure game,

with a classic point-and-click core game mechanic.

Storyboard Interpretation Technology Used for Value-based STEM Education in Digital Game-based Learning Contexts

79

Like other adventure games, the protagonist has to

solve puzzles to progress in the game. Within Ex-

perimento Game, the player deals with two different

moral dilemma situations, which are implemented as

a trigger for two major topics:

(I) Will I share my last mouthful of water with

a stranger? This moral dilemma triggers the

topic of how to produce drinking water/ meth-

ods of purifying water.

(II) Will I stop my grandmother from burning her

garbage on the road? This moral dilemma is

triggering the topic of waste separation.

The moral dilemmas are situations where players

weigh the consequences of their choices carefully, be-

cause there are at least two or more values battling

against each other and there is no optimal answer or

choice (Schuldt, 2017).

2.1.3 Driving Value-based STEM Education

How can ethical values be successfully promoted in

STEM subjects?

Moral concepts and moral stances are not only

special characteristics that set us apart, but also ed-

ucational capabilities. The importance of successful

value promotion is therefore extremely significant in

terms of individual development. The most important

thing here is, that values should be conveyed and im-

parted during childrens early formative years as part

of real life and in relation to everyday life as much as

possible (von Siemens, 2017).

This is where STEM education comes in: Any-

one dealing with science and technology issues will

not be able to avoid reflecting on them, making as-

sessments and taking decisions. Therefore, there is

no need for new subjects to be introduced: The di-

dactic approaches simply need to be shaped accord-

ingly. New approaches are therefore required, such as

DGBL, combined with value-based issues.

Digital games are able to engage learners on an af-

fective, behavioral, cognitive, and sociocultural level

in ways few other learning environments are able to

(Plass et al., 2016). Digital games have the poten-

tial to unleash motivation and interest for science and

technology themes.

Since digitization also affects the education sys-

tem, teaching methods should be adapted appropri-

ately. Learning and especially DGBL in the sense

of acquisition of knowledge and its application re-

quires interactivity, contextualization and goal ori-

entation (Schuldt et al., 2017). Motivation, player

engagement, adaptivity, graceful failure and feed-

back systems are also influencing factors in DGBL-

environments (Plass et al., 2016).

2.2 Storyboarding

When Digital Game-Based Learning goals and tasks

are ambitious, related systems are easily becoming

complex. Storyboarding is a methodology of the sys-

tematic reliable design of Digital Game-Based Learn-

ing applications.

The authors rely on the basics as introduced by

(Jantke and Knauf, 2005) and confine themselves to

those notions and notations needed for the purpose of

characterizing serious games. Recent work on story-

boarding digital games such as (Arnold et al., 2013c;

Jantke and Knauf, 2012; Schuldt, 2017), e.g., is worth

some comparison. Storyboards are described as finite,

hierarchically and structured graphs.

”The composite nodes are named episodes,

whereas the atomic nodes are named scenes.

Composite nodes may be subject to substi-

tution by other graphs. In contrast, atomic

nodes have some semantics in the underlying

domain.” (Arnold et al., 2013b)

2.2.1 Storyboarding as a Methodology of Game

Design

The authors interpret digital storyboarding as a

methodology that is suitable for anticipating user ex-

perience of media interaction including game play

and learning.

”Storyboarding means the organization of ex-

perience.” (Jantke and Knauf, 2005)

Therefore, storyboarding can be understood as a

methodology of didactic design. The authors refer

to more detailed explanations by (Krebs and Jantke,

2014). Storyboarding enables authors to incorpo-

rate psychological and/or pedagogical positions into

a technologically enhanced educational framework

such as a gaming module like Experimento Game.

2.2.2 Storyboarding for Experimento Game

Games of the adventure genre are mostly story-

driven, meaning that a good story is a fundamental

part of this type of game (Fernandez-Vara and Oster-

weil, 2010). Therefore, the two moral dilemma situ-

ations in Experimento Game (see 2.1.2 Experimento

Game: A New Path of Experimento) are embedded

into a whole story. In addition to a tutorial level, there

are two more levels covering different topics:

• Level 1: How to produce drinking water? The

method of purifying water.

• Level 2: How to protect the environment? Sepa-

rating materials for recycling purposes.

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

80

The flexibility of storyboards allows to connect

seamless gameplay, dilemma situations and learning

experiences.

3 TECHNOLOGY AND

DEVELOPMENT

As mentioned previously, the Experimento Game is

an adventure game with sorting puzzles. In order to

progress in the game, the players make decisions and

solve puzzles. The core game mechanics are similar

to those of classic point-and-click games. The Players

only need a mouse (or finger for the tablet version) as

an input device. The Experimento Game is a short 2D

Game and has been developed with UNITY 3D.

3.1 Storyboard Interpretation

Technology for Experimento Game

The Experimento Game uses the Storyboard Interpre-

tation Technology (SIT) by Fraunhofer IDMT. The

essence of this approach is to make digital story-

boards immediately executable. SIT includes a toolkit

that supports the creation of storyboards and ensures

the integration into software products. The defini-

tion of a digital structure for dynamic stories and

rules for interpreting these stories are an additional

part of SIT. The technology has already been used

in previous projects by Fraunhofer IDMT for creat-

ing highly complex story-driven applications (Arnold

et al., 2013c; Arnold et al., 2013b).

3.1.1 Features of SIT

Depending on the requirements of the Experimento

Game, it was necessary to advance SIT. However, sto-

ryboards are now stored in JSON data and no longer

in an online RDF database in comparison to (Arnold

et al., 2013c). New tools support the story authors

to create a tabular storyboard. Like the traditional

storyboards, the digital tabular storyboard contains

drawings and descriptive texts, as well as control in-

formation for the game. More information about the

technology of the Storyboard Editor was published in

(Schuldt, 2017). A parser converts the tabular story-

board into a JSON file that can be interpreted by the

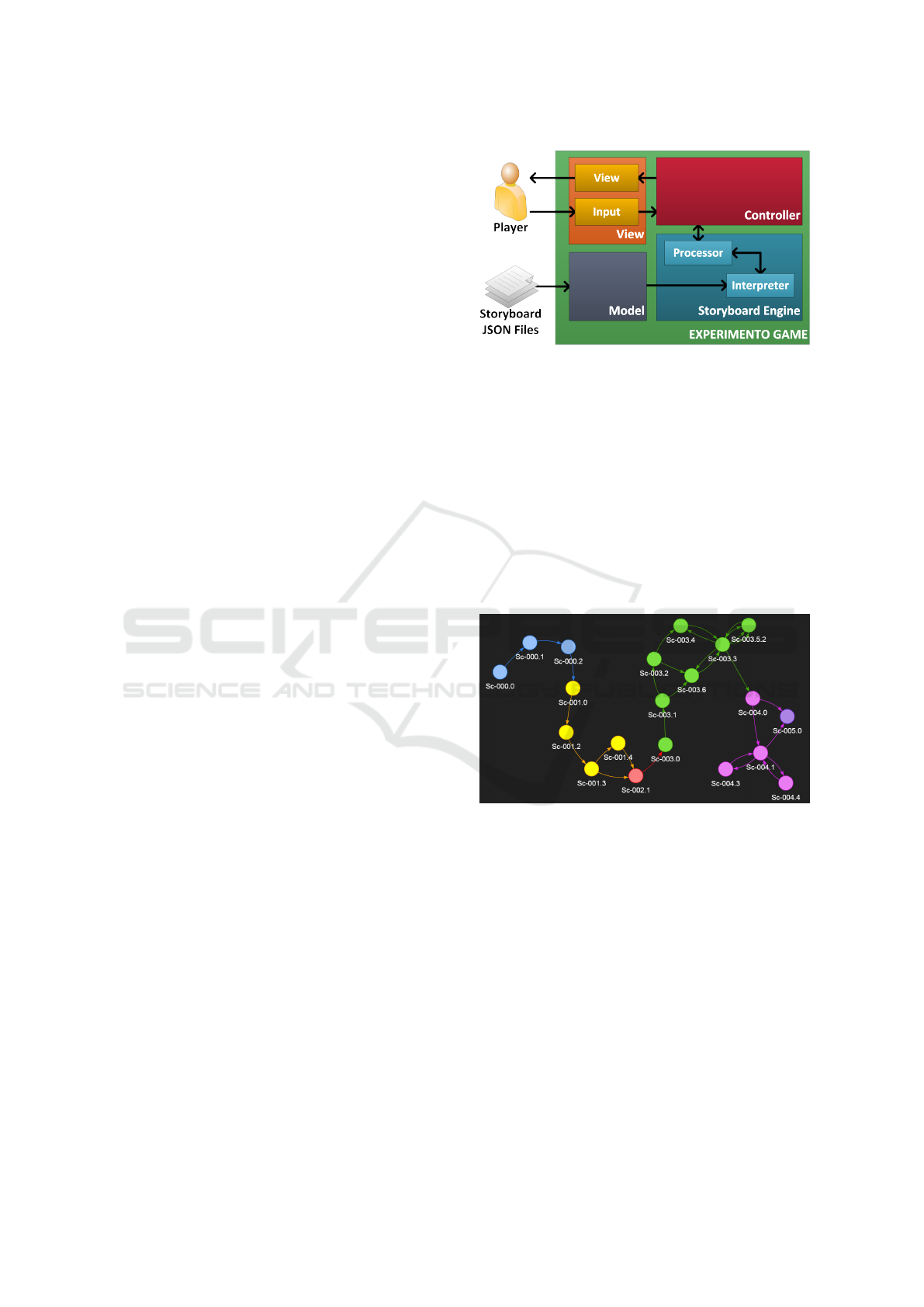

storyboard engine module (see Figure 2).

Now, the storyboard engine contains an interpreter

and a processor. The interpreter understands the struc-

ture of the storyboard files and reads the control in-

formation from the storyboard. The interpreter sends

this information to the processor. The processor is

Figure 2: System design of the Experimento Game.

connected to the game interfaces and processes the

control commands in the game immediately.

The storyboard engine reads the nodes from the

storyboard, executes control commands and reacts to

the players feedback. Depending on game events the

storyboard engine manages the progress in the game.

Therefore the storyboard engine has all relevant data

like the node structure of the storyboard (see Figure 3)

or the conditions for the transitions. It is not intended

to read any of the inscriptions in the storyboard graph

below, but to get an impression of some storyboard as

a whole.

Figure 3: Shows the storyboard of the tutorial level. Dots

represents nodes, arrows represents possible transitions.

The color of the dots indicates the corresponding subcat-

egory of a node.

3.1.2 Application Area of SIT

The use of SIT not only allows game developers

to write a story, but also to create adaptive game-

play content. For instance, the story in Experimento

Game adapts, depending on the player’s decision in

the dilemma situations. Finally, the use of SIT im-

proves and accelerates the development process. The

following positive experiences have been made with

the use of SIT:

• Storyboard authors don’t need a long training pe-

riod for the Storyboard-Tool. They are familiar

Storyboard Interpretation Technology Used for Value-based STEM Education in Digital Game-based Learning Contexts

81

with the traditional tabular storyboard user inter-

face.

• SIT reduces the workload during development.

Storyboard authors and developers can work sep-

arately from each other.

• Changes to the storyboard can be implemented

quickly.

• An assitstance system uses automatic input

checks to prevent incorrect storyboards.

The use of SIT has also demonstrated the limits

of the current technology. Although the limitations

have not affected the gaming design process of the

Experimento Game, future research should solve the

current drawbacks:

• SIT cannot be used for open-world storyboards.

• The mechanics of arcade games are hard to turn

into a storyboard.

3.2 Development

At the beginning of the project there were some tech-

nical challenges, like the cross-platform capability of

the game and the support of low performance devices,

according to the usual school equipment. In addition

to these challenges, the game should be suitable for

various technical infrastructures. A further challenge

was to create a satisfying game for the target group.

Throughout the entire development cycle, we used us-

ability engineering to improve the game’s user expe-

rience.

3.2.1 Technical Challenges

To support lower performance devices certain design

decisions have been made and special techniques have

been used. For instance, there are only 2D objects

without a polygon-geometry in the game. All sprites

are assigned to one of eleven render layers. Two lay-

ers are for the graphical user interface elements and

nine layers for the 2D objects in the game.

To reduce rendering effort, the game automati-

cally disables objects that are located outside of the

camera view. To get a quick access to objects in the

same location the game uses a location map with a

grid.

Furthermore a state-engine was built to separate

the different states in the game and to split the com-

plexity of the code with 10 states (Initialization,

Menu, (Un-)Load, Play, etc.). The game will be

released in different regions such as Africa, South

America and Germany, so all texts in the game are

interchangeable. Separate language files make it eas-

ier to add new languages or update existing texts. The

design has simple 2D graphics and is an abstraction of

the real world, to be appealing to a variety of cultures.

The environment is not similar to any certain region.

Depending on the technical infrastructure there is

an online- and an offline-version of the game avail-

able.

3.2.2 Game Mechanics

To ensure that players are familiar with the con-

trol mechanics of a point-and-click game, there is a

tutorial-level as introduction implemented.

There are two puzzles in the game, both uses the

same mechanics and game rules. During a time of

approx. 60 seconds, the players have to sort objects.

During this time objects appear and move from left to

right like on a conveyor belt. In the first mini game

the player has to drag components of a water filter

and drop them in the correct order into an empty filter

(see Figure 4). If the assignment is correct, the score

increases.

Figure 4: Screen-shot from first Mini-Game.

In order to increase the replayability of the game,

there is a hidden score. The players get points for var-

ious actions during the game. At the end of the game

a result screen shows what points have been awarded.

The players achieve points for:

• playing time is less than 12 minutes,

• pick up of waste while playing,

• score of the first mini game (build water filter),

• score of the second mini game (recycling).

4 STUDY AND RESULTS

Going beyond the concept of usability, user experi-

ence is a holistic approach that embraces the complete

effects of a users experience before, while and after

using an interface (Deutsches Institut f

¨

ur Normung,

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

82

2011). It also includes aesthetic or emotional factors

such as joy or fun while using a product.

In order to summative examine the games user ex-

perience (UX) according to the target group of 11- to

13 year old students a survey-based study including a

playtest of the final prototype has been carried out in

early July 2017.

A suitable usability and UX concept was already

conceived right in the beginning and has been ad-

justed systematically in the projects course to opti-

mize the game in an iterative design process (Schuldt,

2017). In preparation of the study, a pretest was con-

ducted in June 2017 to test the prototype on the one

hand and to test the research setting and the instru-

ments (see 4.2 Methodological Study Design) on the

other hand. It confirmed a playtime of around 15

minutes and an adequate understanding of the ques-

tionnaire as well as a working log file analysis. Sub-

sequently, minor changes were made in the games

source code and the questionnaire according to usabil-

ity issues.

4.1 Objectives and Research Interests

The UX of Experimento Game formed the primary re-

search subject of this study. One goal of the study was

to evaluate the game’s suitability for school students

and the context of lessons and the specific curricu-

lum. Besides, there was a strong interest to examine

the impact of the game using dilemma situations as a

method to foster reflection about norms and values in

class.

The study design was set up to give an answer to

the following research questions:

(I) UX: How is the overall user experience of Ex-

perimento Game within the target group of

highschool students at the age of 11 to 13?

(II) Dilemma: How does the target group of high-

school students at the age of 11 to 13 cope with

decision making in the moral dilemma situa-

tions?

(III) Learning: How is the games impact on the

students awareness of the environment issues

mentioned in the story?

(IV) Context of use: How suitable is the game for

the use in class?

4.2 Methodological Study Design

The challenge was to set up a study design being close

to the future context of use of the game in classes with

young students. The whole setting should fit into a

school lesson and should be easily to understand and

to be answered in short time. Therefore, the following

instruments were employed:

• standardized questionnaire including the topics:

personal data, user experience, emotions while

playing, decision making, learning with the game;

• user experience questionnaire (UEQ) in simpli-

fied language as part of the main questionnaire:

set of 26 pairs of opposite items belonging to the

scales attractiveness, perspicuity, efficiency, de-

pendability, stimulation, and novelty. (Hinderks

et al., 2012; Hinderks et al., 2014; Hinderks et al.,

2017);

• log files: e.g. total playing time, usage of sound,

choice of character, decisions made in dilemma

situations, scores in mini games and other chal-

lenges.

Within the scope of the study, the game was tested

and evaluated by the target group of 11 to 13 year-old

high school students in Germany using a setting inte-

grated in a school lesson. There was first an introduc-

tion by the accompanying scientist and the teacher.

Afterwards the students were asked to play the game

on their own while log files were collected and the

scientist kept the minutes in an observation protocol.

Finally, the students filled in a questionnaire to evalu-

ate the game and their experiences made.

The sample of students taken was not representa-

tive, but self-selective as existing school classes were

asked to take part in the study. The questionnaires

were imported and analysed by using the survey soft-

ware SPHINX to generate descriptive data. The UEQ

Data Analysis Tool by Dr. Martin Schrepp see (Hin-

derks et al., 2017) was applied to analyse the items

belonging to the user experience questionnaire. The

data mining was realized by implementing a data ac-

quisition tool and a final analysis in Microsoft Excel.

The survey was conducted in German language

and then translated for this paper.

4.3 Study Results

The examination was conducted at a secondary school

in Lower Saxony, Germany in June 2017. Altogether

n=49 participants tested the game and filled in the

questionnaire. Furthermore, data were collected via

data mining and an additional observation protocol.

In addition, n=2 teachers filled in the questionnaire

concerning the teacher’s view. The students taking

part attended classes in 5th and 6th grade and were

aged from 9 to 14 years; there were 51 % male and

46,1 % female (n=25 male, n=23 female, 1= un-

known). Most of them were experienced in playing

digital games at least sometimes, but - if at all - very

Storyboard Interpretation Technology Used for Value-based STEM Education in Digital Game-based Learning Contexts

83

exceptionally had the chance to get in touch with it as

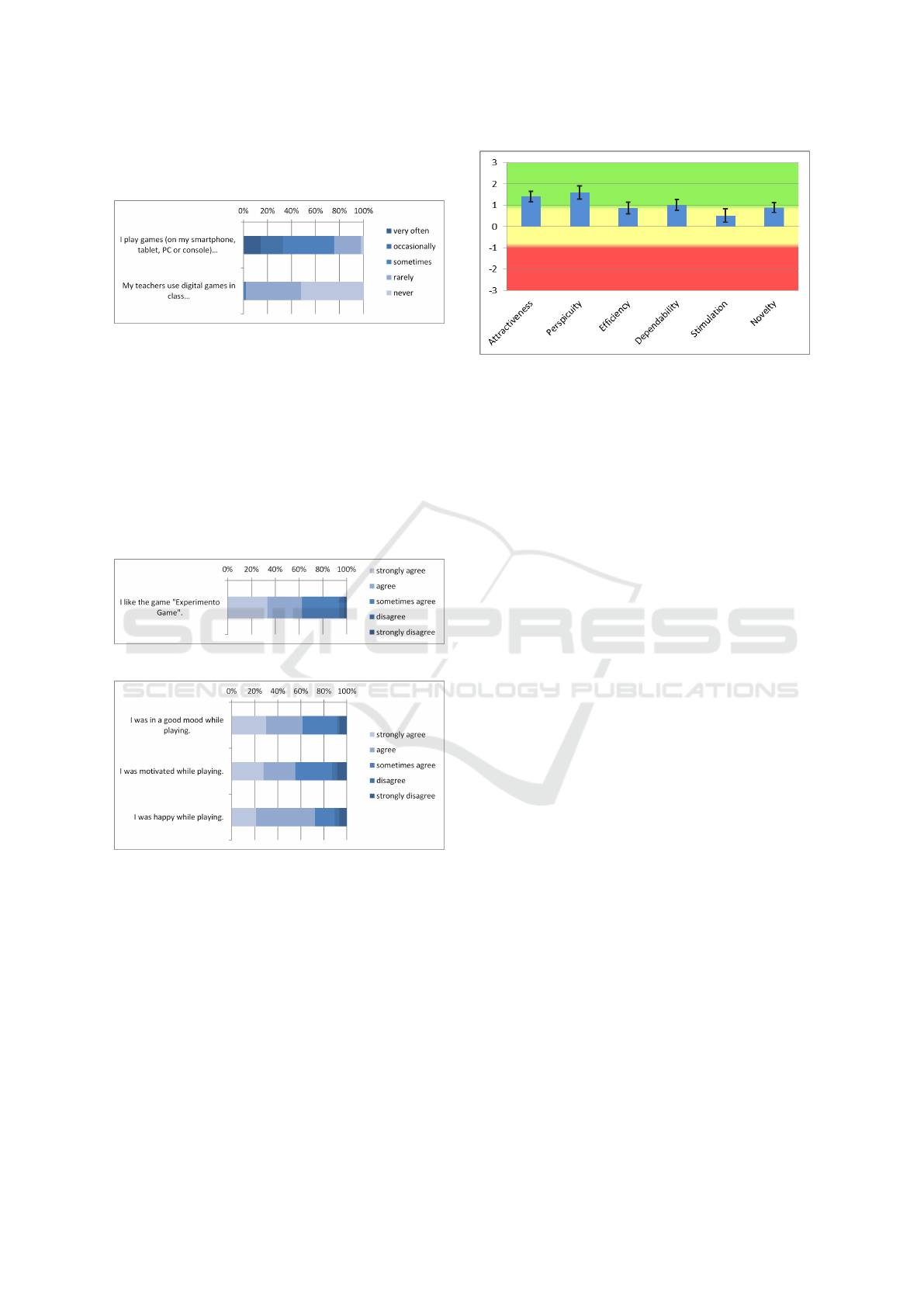

a method in lessons. (see Figure 5)

Figure 5: Previous experience with computer games.

4.3.1 Results UX

On the whole, there is a positive overall impression

of the game as the majority of the test persons (62.5

%) claimed they liked Experimento Game and only

few persons (6.3 %) disagreed. (see Figure 6) In ad-

dition, similar results showed up concerning the stu-

dents emotions while playing: Most of the test per-

sons were in a good mood, felt motivated as well as

happy when playing the game. (see Figure 7)

Figure 6: Assessment of the game by the students.

Figure 7: Emotions while playing.

Regarding the scales of the UEQ, the game was

altogether rated positively by the test persons. (see

Figure 8) For explanation: According to (Hinderks

et al., 2017) the values between -0.8 and 0.8 repre-

sent a neutral evaluation of the corresponding scale,

and values greater than 0,8 represent a positive eval-

uation. Due to the calculation of means over a range

of different persons with different opinions and an-

swer tendencies values above +2 are rather unlikely

to achieve.

• The dimension attractiveness means the over-

all impression of the evaluated system. The re-

sults given in the UEQ concerning Experimento

Figure 8: UX results according to the UEQ-Scales.

Game correspond to the positive students answers

in (Figure 6) and show satisfying trends (see Fig-

ure 7).

• Dimension quality of use:

– The scale perspicuity measures if a system is

easy to understand and to learn. The test per-

sons obviously did not have any severe prob-

lems to use the game.

– The scale efficiency measures, if the users can

work quick and efficient with a system. It

showed satisfying results in the context of a

digital game.

– The scale dependability measures how safe

and predictable the interactions are. The results

confirm that the adolescent testers were gener-

ally able to cope with the game. Some prob-

lems were mentioned in the free-text fields of

the main questionnaire and mostly referred to

the high speed of the mini games or some minor

usability issues that were adjusted afterwards.

• Dimension design quality:

– The scale stimulation measures how interest-

ing, stimulating and motivating the system is.

Some helpful comments for further improve-

ments of the game were given by the test per-

sons concerning implementing more characters

to choose/ to create, and raising the tension of

the game through leaving out predictable parts.

– The scale novelty refers to the extent of innova-

tion and creativeness of the design which is in

the case of ”Experimento Game” mainly posi-

tively rated.

Accordingly, the majority of the students taking

part in the study accepted the game as part of their

lesson and could imagine to play more games like

Experimento Game in class (82,9 %). For the most

part they felt that comfortable with the game that they

would also recommend it to friends. (see Figure 9).

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

84

Figure 9: Suitability for learning.

4.3.2 Results Dilemma

Generally, the students identified themselves in the

dilemma situations and told phrases like ’To me all

the waste lying around was ugly.’, ’Those poor birds’,

’Why is grandma that dumb? Thats simply not

done!’. In both dilemma situations decision making

felt rather easy to most of the test person (see Figure

10). Roundabout one fifth of them had difficulties to

get aware of the consequences of their decision mak-

ing as well as to take a decision. (see Figure 11)

Figure 10: Feelings about decision making.

Figure 11: Awareness of consequences.

The dilemma situations already led to first discus-

sions in class within the test session. Thus, they serve

the purpose of fostering moral argumentations about

contents relevant to the students curriculum. The test

persons decision behavior in the dilemma situations

did not yet appear completely balanced (see Figure

12), but there still is a need for a greater sample to

see a clear tendency. Altogether, the students defi-

nitely experienced the use of dilemmata as one excit-

ing method to get involved in new topics.

Figure 12: Distribution of responses in dilemma situations.

4.3.3 Results Learning

The results concerning UX (also including some free-

text comments as well as observations in class) clearly

show acceptance among the target group of the game.

More than half of the test persons agreed to have

learned something new while playing the game. (see

Figure 13) An even bigger share (> 74 %) claimed

that the game drew their attention to the importance

of the environments topics treated in the story. A sim-

ilar amount of test persons would like to play Experi-

mento Game in class.

The topics chosen are relevant for the curriculum.

And, what’s more, the environment-related dilemma

situations of this module can be used in classic STEM

subjects, but are also suitable for further subjects like

ethics. Although the game can only treat limited top-

ics, its interactive features foster tackling with envi-

ronmental issues and serve as one method get students

involved.

Figure 13: Assessment of learning with Experimento

Game.

4.3.4 Results Context of Use

The logfile data concerning playing time (around 15

minutes) and scores (mini games, collecting trash,

and time score) confirmed the suitability of the game

for its usage in lessons as well as an adequate chal-

lenge for highschool students. (see Figure 14).

Storyboard Interpretation Technology Used for Value-based STEM Education in Digital Game-based Learning Contexts

85

Figure 14: Logfile data - Times and scores.

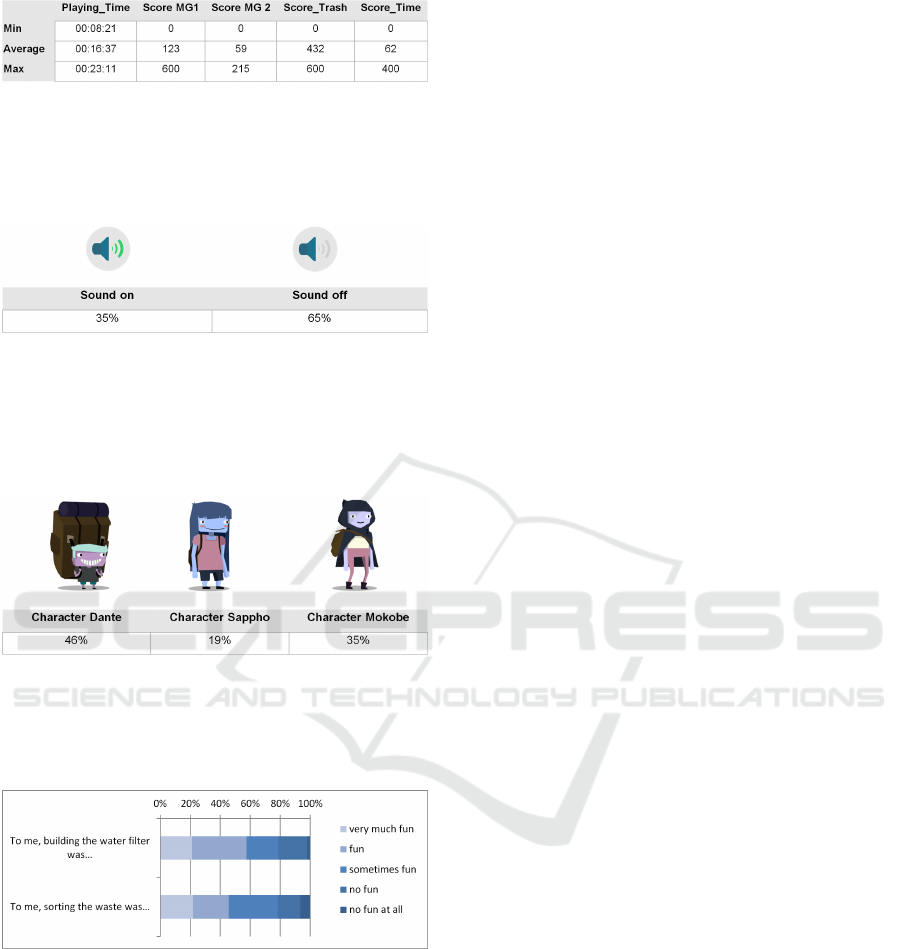

The game was used with as well as without sound

while testing. (see Figure 15) It is working in both

situations.

Figure 15: Used sound settings.

It is justified to implement a choice of character as

all of them were chosen as avatar. Dante and Mokobe

were the most popular among the test persons. (see

Figure 16)

Figure 16: Logfile data - Choice of character.

The logfile data as well as students feedback (see

Figure 17) shows that the recycling mini-game was

more difficult than the water filter mini-game.

Figure 17: Feelings about playing mini games.

There was also a teacher-version of the question-

naire asking for their opinion about the game and it’s

suitability for classes. Due to the small teacher’s sam-

ple, we will not give a detailed description of the re-

sults.

5 DISCUSSION

The overall user experience of Experimento Game

within the target group of highschool students was

rated positively, especially the dimensions attractive-

ness and perspicuity. Only the dimension stimulation

was rated neutral. For some students the decisions

were not too difficult in the moral dilemmas, but not

all of them were aware of the consequences of their

decision. The study showed that the games impact

on the students awareness of the environment issues

mentioned in the story is quite high and therefore a

good method for learning in STEM contexts. Teach-

ers and students appreciated the Experimento Game

approach and rate the game suitable for the use in

class.

The study underlies several limitations concerning

the target group and the specifications of the survey.

There were strong limitations concerning time capac-

ities (school lesson) as well as suitabiliey of the re-

search method for rather young high school students

(length, comprehension, focusing the overall impres-

sion of the game). According to the content of the

survey, it would also be desirerable to distinguish the

emotions while playing between overall playing ex-

perience and decision making in future research. The

emotions in the survey refer to the overall playing ex-

perience, but not to how specific parts of the dilemma

story was experienced by the users (cf. 4.3.2 Results

Dilemma).

The underlying user-centered design approach al-

lowed for a continuous adjustment of the game during

development. In the final UX-Study we got positive

feedback from students and teachers equally.

The questionnaire was adapted to the target group

and improved through a Pretest-Setting.

Games as educational media are time-consuming

and quite expensive to produce and then unfortunately

not always accepted. They can and should not stand

alone, therefore we supported teacher with an extra

handout with suggestions of how to embed the game

in their lessons.

Extensions within the Experimento-Program are

possible, although there are challenges in spreading

OER, due to the publishers, thus making no profit

with these offers.

SIT enables easy language variants and different

areas of application (for instance, in our case the story

must fit for different cultures).

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

86

6 CONCLUSIONS AND

OUTLOOK

Experimento Game is designed to motivate students

intrinsically and activate environmental awareness

and sustainability. The game enables decisions in a

”sheltered” gaming environment and stimulates dis-

cussions for reflection of different behavior.

Experimento Game fits into today’s everyday

habits of children and adolescents; the majority con-

sumes regularly games on different platforms (Feier-

abend et al., 2016). Currently, digital games are used

rarely by teachers in the classroom; the infrastructure

in schools is given in many places, that this would in

principle be possible (Kantar TNS, 2016).

The novelty of the project is to use SIT to develop

tasks and teaching materials that bring STEM topics

to life and enable a fun way of learning. Many cur-

ricula still focus on conducting exams. Students learn

more easily and more sustainably if they actively use

new knowledge instead of memorizing it.

The Experimento Game was very well received in

the study by the subjects. It has not only caused many

positive reactions among the participants, but has also

enabled them to experience their own personal experi-

ences. It has proved to be a suitable game to introduce

environmental education in the classroom and to stim-

ulate reflection on the behavior of different actors.

The teachers confirmed both the acceptance of the

pupils as well as their own. They thought the material

provided was helpful and they would like to use the

game in future lessons.

Experimento Game can contribute to education as

a suitable offer to students to modernize and enrich

learning, and thus the goal of a meaningful digital ed-

ucation in schools.

In the future, it is recommended to transfer the

game to other cultures and languages as well as to

elaborate further modules that address new content

and controversy. The numerous comments from the

testers should be used to make future developments

even more interesting and to respond more intensively

to the previous experiences of the potential users. A

mobile version of the game, such as a tablet version,

is the next step in development.

The Storyboard Interpretation Technology was

used to implement a story. This Technology made it

possible to write stories easier, faster and more effec-

tive. In the future, SIT should be tested to see whether

it can also be used in other learning areas, such as in-

teractive virtual laboratories.

Serious Games must have a pedagogic-didactic

quality and should focus on the application of knowl-

edge. The matter in question and the content design

must be measured by the fact that they have an actual

added value about real experimentation, discussion,

etc..

Further research questions are interesting to inves-

tigate: (a) Do the emotions of the students have an in-

fluence on the playing experience with Experimento

Game? (b) Is SIT as an authoring tool suitable for

universal use?

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the fruitful col-

laboration with their customer, Siemens Stiftung. As

a non-profit corporate foundation, Siemens Stiftung

promotes sustainable social development, which is

crucially dependent on access to basic services, high-

quality education, and an understanding of culture.

To this effect, the Foundations project work supports

people in taking the initiative to responsibly address

current challenges. Together with partners, Siemens

Stiftung develops and implements solutions and pro-

grams to support this effort, with technological and

social innovation playing a central role. The ac-

tions of Siemens Stiftung are impact-oriented and

conducted in a transparent manner. www.siemens-

stiftung.org

REFERENCES

Arnold, S., Fujima, J., and Jantke, K. P. (2013a). Story-

boarding Serious Games for Large-scale Training Ap-

plications. In 5th International Conference on Com-

puter Supported Education, pages 651–655.

Arnold, S., Fujima, J., Jantke, K. P., Karsten, A., and Simeit,

H. (2013b). Game-Based Training of Executive Staff

of Professional Disaster Management: Storyboarding

Adaptivity of Game Play.

Arnold, S., Fujima, J., Karsten, A., and Simeit, H. (2013c).

Adaptive Behavior with User Modeling and Story-

boarding in Serious Games. In Yetongnon, K., Di-

panda, A., and Chbeir, R., editors, Proceedings:

2013 International Conference on Signal-Image Tech-

nology & Internet-Based Systems, pages 345–350,

Los Alamitos, California and Washington and Tokyo.

Conference Publishing Services, IEEE Computer So-

ciety.

Avram, M. (2014). The neural foundation

of moral decision-making. http://nbn-

resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:19-175137.

Avram, M., Hennig-Fast, K., Bao, Y., P

¨

oppel, E., Reiser,

M., Blautzik, J., Giordano, J., and Gutyrchik, E.

(2014). Neural correlates of moral judgments in first-

and third-person perspectives: implications for neu-

roethics and beyond. BMC neuroscience, 15:39.

Storyboard Interpretation Technology Used for Value-based STEM Education in Digital Game-based Learning Contexts

87

Deutsches Institut f

¨

ur Normung (2011). Ergonomie

der Mensch-System-Interaktion - Teil 210: Prozess

zur Gestaltung gebrauchstauglicher interaktiver Sys-

teme (ISO 9241-210:2010); Deutsche Fassung EN

ISO 9241-210:2010, volume EN ISO 9241,210 of

Deutsche Norm. Beuth, Berlin, januar 2011 edition.

Feierabend, S., Plankenhorn, T., and Rathgeb, T. (2016).

JIM-Studie 2016: Jugend, Information, (Multi-) Me-

dia ; Basisstudie zum Medienumgang 12- bis 19-

J

¨

ahriger in Deutschland. Medienp

¨

adagogischer

Forschungsverbund S

¨

udwest, Stuttgart, november

2016 edition.

Fernandez-Vara, C. and Osterweil, S. (2010). The Key to

Adventure Game Design: Insight and Sense-making.

http://meaningfulplay.msu.edu/proceedings2010/

mp2010 paper 25.pdf.

Fujima, J., Jantke, K. P., and Arnold, S. (2013). Dig-

ital game playing as storyboard interpretation. In

2013 IEEE International Games Innovation Confer-

ence (IGIC), pages 64–71. IEEE.

Greene, J. D., Cushman, F. A., Stewart, L. E., Lowenberg,

K., Nystrom, L. E., and Cohen, J. D. (2009). Push-

ing moral buttons: the interaction between personal

force and intention in moral judgment. Cognition,

111(3):364–371.

Haidt, J. (2001). The emotional dog and its rational tail: A

social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psy-

chological Review, 108(4):814–834.

Hinderks, A., Schrepp, M., Rauschenberger, M., Olschner,

S., and Thomaschewski, J. (2012). Konstruktion eines

Fragebogens f

¨

ur Jugendliche Personen zur Messung

von User Experience. In Brau, H., Lehmann, A.,

Petrovic, K., and Schroeder, M. C., editors, Usabil-

ity Professionals 2012 - Tagungsband, Konstanz, Ger-

many, September 9-12, 2012, pages 78–83. German

UPA e.V.

Hinderks, A., Schrepp, M., and Tomaschewski, J.

(2014). Evaluation des UEQ in einfacher Sprache

mit Sch

¨

ulern. In Butz, A., Koch, M., and Schlichter,

J., editors, Mensch und Computer 2014 - Tagungs-

band: 14. fach

¨

ubergreifende Konferenz f

¨

ur Interak-

tive und Kooperative Medien - Interaktiv unterwegs

- Freir

¨

aume gestalten, volume v.2014 of Mensch &

Computer – Tagungsb

¨

ande / Proceedings. De Gruyter

Oldenbourg, Berlin.

Hinderks, A., Schrepp, M., and Tomaschewski, J.

(2017). UEQ-Online: User Experience Questionnaire.

http://www.ueq-online.org/.

Jantke, K. P. and Knauf, R. (2005). Didactic design

through storyboarding: Standard concepts for stan-

dard tools. In Proceedings of the 4th Interna-

tional Symposium on Information and Communica-

tion Technologies (ISICT), pages 20–25. Trinity Col-

lege Dublin: Computer Science Press.

Jantke, K. P. and Knauf, R. (2012). Taxonomic concepts for

storyboarding digital games for learning in context. In

4th International Conference on Computer Supported

Education (CSEDU) 2012, volume 2, pages 401–409.

SciTePress.

Kantar TNS (2016). Sonderstudie Schule Digital:

Lehrwelt, Lernwelt, Lebenswelt: Digitale Bil-

dung im Dreieck Sch

¨

ulerInnen-Eltern-Lehrkr

¨

afte.

http://initiatived21.de/app/uploads/2017/01/

d21 schule digital2016.pdf.

Krebs, J. (2013). Moral Dilemmas in Serious Games. In

Proc. of the International Conference on Advanced In-

formation and Communication Technology for Educa-

tion (ICAICTE 2013), pages 232–236. Atlantis Press.

Krebs, J. and Jantke, K. P. (2014). Methods and Technolo-

gies for Wrapping - Educational Theory into Serious

Games. Proceedings of the 6th International Confer-

ence on Computer Supported Education, pages 497–

502.

Plass, J. L., Homer, B. D., and Kinzer, C. K. (2016). Foun-

dations of Game-Based Learning. Educational Psy-

chologist, 50(4):258–283.

Schuldt, J. (2017). Fachtagung MINT und Werte:

Einsatz von Serious Games zur Wertebildung im

naturwissenschaftlich-technischen Unterricht. Work-

shop.

Schuldt, J., Sachse, S., Hetsch, V., and Moss, K. J. (2017).

The Experimento Game: Enhancing a Players’ Learn-

ing Experience by Embedding Moral Dilemmas in Se-

rious Gaming Modules. In Auer, M. E. and Zutin,

D. G., editors, Online Engineering & Internet of

Things: Proceedings of the 14th International Confer-

ence on Remote Engineering and Virtual Instrumen-

tation REV 2017, held 15-17 March 2017, Columbia

University, New York, USA, pages 561–569. Springer

Science and Business Media and Springer, Cham.

Sellmaier, S. (2008). Ethik der Konflikte:

¨

Uber den

moralisch angemessenen Umgang mit ethischem Dis-

sens und moralischen Dilemmata, volume 2 of Ethik

im Diskurs. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart, 1. edition.

Sicart, M. (2013). Moral Dilemmas in Computer Games.

Design Issues, 29(3):28–37.

Siemens Stiftung (2017a). Exper-

imento. https://www.siemens-

stiftung.org/en/projects/experimento/.

Siemens Stiftung (2017b). OER News.

https://www.siemens-stiftung.org/en/projects/media-

portal/oer-news/.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cul-

tural Organization (2012). Paris OER

Declaration: Documentary resources.

http://www.unesco.org/new/en/communication-and-

information/access-to-knowledge/open-educational-

resources/documentary-resources/.

von Siemens, N. (2017). Fachtagung MINT und

Werte: Wie Wertebildung im Unterricht gelingen

kann. https://fachtagung-mint-und-werte.siemens-

stiftung.org/.

Wimmer, J. (2014). Moralische Dilemmata in digitalen

Spielen. Wie Computergames die ethische Reflexion

f

¨

ordern k

¨

onnen. Communicatio Socialis, 47(3):274–

282.

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

88