Digital Media’s Alteration Mechanism for Informal Learning

Otto Petrovic

Institute for Information Science and Information Systems,

Karl-Franzens-University of Graz, Austria

Keywords: Alterations by Digital Media, Informal Learning, Learning Objectives, Learning Theory, Epistemology,

Participatory Action Research, Autovideography.

Abstract: The main part of human learning happens en passant and mostly outside of an educational institution - called

informal learning. Even pupils and students spend more time in front of digital media screens than in formal

settings inside schools. Thus, their learning is strongly impacted by the use of digital media in everyday life.

Current research, educational practice, and design of learning systems have their focus mostly on courseware

and distance education for formal settings. The current study captures real-life learning episodes in the

domains of cognitive, affective, and psychomotor learning using autovideography. Additional episodes are

captured by the author applying participatory action research (PAR) in extensive field studies in different

cultures. The episodes are analyzed, using different learning theories to develop a category system of

alteration mechanism for informal learning using the approach of grounded theory. The main alteration

mechanism identified is the extension of linear learning content to a multi-dimensional, perception sphere that

is characterized by high interactivity and contingency. To utilize this alteration mechanism, one possible

conclusion is that educators should neither stick to pure transfer of knowledge nor retreat to a facilitator, the

latter of which is empty of content.

1 INTRODUCTION AND

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

The main part of human learning happens en passant

as a by-product of something else, mostly outside of

an educational institution, and is naturally embedded

in human life. It is non-intentional with no a priori

objectives. We call this kind of learning informal

learning. The 21

st

century is characterized by the

advent of digital media and its ubiquitous use by

humans as well as by machines to interact among

each other. Young people spend, even during their

life span with the highest share of formal education,

more time in front of digital media screens than in

formal settings inside schools. Better understanding

of digital media’s alteration mechanism should help

to improve practice of informal learning by learners,

methods of teaching, and envisioning and design of

new learning environments. The aim of the study is

not to tell educators how to better teach in the age of

digital, but to have a better understanding of digital

media’s alteration mechanism to become capable

combining different mechanisms to support learners

in the best possible way. Therefore, the focus of the

present study is to understand the alteration

mechanism of digital media which are used by people

in their everyday life and not on dedicated courseware

like MOOCs or systems for distance education. To

broaden the perspective, which is currently focused

on transfer knowledge from the teacher to the learner,

deeper insights into basic characteristics of different

learning theories and epistemologies are necessary.

To gain a better understanding for digital media’s

alteration mechanism on informal learning, we firstly

capture real-life learning episodes via pictures,

videos, and text annotations in the domains of

cognitive, affective, and psychomotor learning. Next,

we analyze the learning episodes through the

‘glasses’ of the two main learning theories of the 20

th

and 21

st

century, objectivism and constructivism, to

identify basic alteration mechanisms. Finally, based

on the analysis we develop a category system for

those mechanisms.

Petrovic, O.

Digital Media’s Alteration Mechanism for Informal Learning.

DOI: 10.5220/0006772303210330

In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2018), pages 321-330

ISBN: 978-989-758-291-2

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

321

2 INFORMAL LEARNING

2.1 Definition

Learning can be defined as acquiring new or modify

existing knowledge, skills, competencies, and

perceptions which lead to alterations in thinking,

feeling, and behavior. Depending on the chosen

definition of learning and its measurement only

around 25 % of it happens in formal or non-formal

settings. Formal learning is systematic organized

learning within a formal learning system like

universities or schools with learning specified

objectives and degrees awarded by the system. Non-

formal learning is similar but conducted outside of the

formal learning system, e.g. in organizations for

further education, vocational training settings, or

youth organizations.

The predominant part of learning happens in

informal settings. In these settings learning is not the

main aim, it happens en passant as a by-product of

something else, e.g. playing a game on the computer,

competing in a bike race, or cheating during an exam.

Very often the contexts for informal learning are day-

to-day situations but it can also be a formal learning

setting where informal learning is not intended.

Normally, informal learning doesn’t lead to a formal

degree, whereby the formal acknowledgment of

outcomes of informal learning is a widely-discussed

topic. Informal learning can happen in different

contexts: Family, school, work, leisure time, or social

communities (Council of Europe, 2000; Ainsworth

and Eaton, 2010; Harring, Witte and Burger, 2016).

In summary, informal learning is characterized

by:

Non-intentionality

Absence of structure

Absence of a priori set objectives,

Occurrence in day-to-day situations outside

of educational institutions

Absence of a reward in the form of a formal

degree

Ongoing, pervasive, and natural connection

with life

2.2 Domains of Learning

As shown below in the section on methodology used

in this study, real-life learning episodes are captured

in the form of videos, pictures, and annotations by

learners. The first step of analysis is assigning them

to certain learning domains. For the purposes of this

study, considered learning domains are based on the

well-established and widely discussed taxonomy of

learning objectives by Benjamin Bloom and his

colleagues (Bloom, Englehart, Furst, Hill and

Krathwohl, 1956; Krathwohl, 2002) However, as

informal learning has per definition no a priori

defined learning objectives, we focus more on

outcomes than on objectives and use the notation of

domains.

The focus of learning in the cognitive domain is

on the ability to recall facts, methods and processes.

Bloom and his colleagues identified six categories of

cognitive learning outcomes with different levels of

difficulty, in that the first must be mastered before the

next. Learning in the affective domain (Krathwohl,

Bloom and Masia, 1973) focusses on perceptions,

attitudes, emotions, values, and norms. Learning in

the psychomotor domain concerns physical

coordination and movement in relationship with

cognitive and affective processes. Examples are

handwriting, doing sports, operating a complex

machine like a car, or playing a computer game.

2.3 Informal Learning from an

Objectivist Point of View

To find different alteration mechanism of digital

media for informal learning we study their impact in

real world learning episodes. As those episodes, like

every real-world phenomenon, are very complex, we

must reduce complexity by using a certain point of

view, which is a dedicated ‘lens’ in form of a theory

of learning. Many of those theories were generated

during the last decades and centuries. They should

explain how people learn and act as a ‘lens’ for

observations in the field. For the purposes of this

study we will look at informal learning through the

lens of objectivism and constructivism and their

related subcategories. For an in-depth analysis of

these theories as well as their relationships to

epistemology see (Harasim, 2017).

The objectivist point of view posits knowledge as

existing objectively beyond our minds, as finite truth.

It is based on the dualism of one’s own mind and the

world around it. The focus of behaviorist learning

theories how particular behavior is changed by

certain learnings. Cognitivism tries to overcome those

limitations of behaviorism by understanding the

‘black box’ of the human mind. The focus of

cognitivist learning theories is to understand mental

processes to promote learning effectively.

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

322

2.4 Informal Learning from a

Constructivist Point of View

Constructivism refers both to a learning theory (how

humans learn) and to an epistemology (the nature of

knowledge). It postulates that humans construct their

own knowledge of the world by experiencing and

interacting. Thus, knowledge is dynamic and

changing, constructed and negotiated in social

context, rather than something absolute and finite.

The role of the teacher no longer is to transfer his

knowledge to the brains of students effectively but to

help them build their own knowledge by creating

supporting environments. Glasersfeld (1995)

emphasizes, that memorization and rote learning are

not useless. But to solve problems that are not exactly

presented during instruction the student requires

conceptual understanding and the ability to rearrange

memorized facts as well as abstract building blocks

and to relate them to other already learned processes

to fit the challenges of a novel problem situation.

Collaborativist learning theory is based on

constructivism and emerged with the advent of

networked computers. The basic assumption is that

computer networking creates new opportunities to

share multiple perspectives, to foster reflective

thinking skills, and to build multidimensional and

multidisciplinary understanding instead of the

emphasis on one ‘correct’ answer, by interacting with

others using online environments.

An example is the significant increase in the use

of self-monitoring devices which create content in

form of vital and performance data and share it with

millions of peers on fitness platforms like Strava

(www.strava.com) and Garmin Connect

(connect.garmin.com). Increased awareness of

exercise and nutrition as well as self-responsibility for

one’s own fitness and health are resulting learnings

(Petrovic 2017b). Figure 1 shows the analyzing

process of such a learning episode within the current

study.

Figure 1: Analysis of road biking in South Korea

considering different learning domains.

3 DIGITAL MEDIA AND ITS

FUNCTIONS

3.1 Definition

For the scope of the present study, media should be

defined as means or channels of communication

between humans, machines and humans, or among

machines, creating a dedicated perception sphere for

the participants of the communication process. We do

not see media just as mean to transport a certain part

of reality, but to communicate certain views on reality

perceived by the creator of the communication

content. Because of this, media are not a substitution

for reality, but a means to communicate individually

perceived reality. The content of this communication

process builds a sphere for the participants of the

process to interpret the content individually (Pietraß,

2016). Primary media functions

The focus of the present study are digital media’s

alteration mechanisms for informal learning. Thus,

the center of analysis are not empirical findings on

changes in different learning settings caused by

digital media or recommendation for using digital

media in the context of informal learning, but

enabling factors for such changes facilitated by

digital media. The difference between those two

perspectives is the actual use of digital media by

humans or machines. This allows firstly, to better

understand the reasons for observed changes in

learning and their relationship to digital media and

secondly, to envision and design new learning

environments. The starting point of the intended

category system of alteration mechanisms are

primary media functions which are properties of

media to support handling of the communication

content (Keil-Slawik and Selke, 1998; Selke, 2008).

Create and delete allows to produce and delete

communication content e.g. symbols like letters,

pictures, videos, drawings, or models. An example of

using this primary function at the level of secondary

function is the ability to make pictures and videos

with omnipresent smartphones. Normally, the creator

of a content assumes its permanency until someone

delete it. Thus, deletion is a related function of media.

Examples of digital medias alteration in deletion are

Snapchat with its value proposition of deletion after

some seconds or contrary, the violent discussion on

the ‘right to be forgotten’ in the universe of digital

media.

Arrange and link facilitates the organization of

communication content. By arranging, the content is

grouped together in spatial proximity within a certain

perception sphere. Examples are digital documents

Digital Media’s Alteration Mechanism for Informal Learning

323

stored in the same folder or organic results of Google

search. Thus, arranging is not a characteristic of the

content itself as the spatial proximity is generated by

human intervention or software algorithm without

changing the content entity. Linking implies a

reference within the communication content to some

other to show relationships. Therefore, it is a property

of the communication content. Examples of using that

primary function are hypertext links or

recommendations on e-commerce sites. Arrange and

link are the core functions for creating a perception

sphere, contrary to a single linear information entity.

Thus, arrange and link is one of digital media’s most

powerful alteration mechanism for informal learning.

Transmit and access comprises the exchange of

information content between humans, humans and

machines, or directly between machines without

human intervention as discussed in the context of

internet of things (Petrovic, 2017c). A core

characteristic of transmit is the existence of a certain

addressee of the communication content. Therefore,

transmit leads to push communication in one-to-one,

one-to-many, many-to-one, or many-to-many

settings. Examples for using that alteration

mechanism on the level of secondary media functions

are sending emails or making video calls. Contrary to

transmit, access doesn’t require any intervention of

communication content’s creator after creation.

Others access the content in the perception sphere in

a pull mode based on their access rights. Examples

are the access of web sites or the use of social media

groups.

3.2 Types of Digital Media

After the widespread use of the personal computers

and the launch of the Internet in 1989 followed by the

rise of social media around 2004, settings like

computer based training and intelligent tutoring

systems, followed by MOOCs (massive open online

learning), PLEs (personalized learning environments)

and ALS (adaptive learning systems), and online

communities of practice became part of learning

processes (Harasim, 2017, Kindle-Position 4178). As

all those systems are designed and used explicitly to

support formal learning, they are not in the focus of

the present study, as it deals with informal learning

and its core characteristic of not-intentionality. In the

present study, the focus lies on digital media used by

learners in their everyday life, e.g. popular social

media sites, online games, or browsing the World

Wide Web. Figure 2 shows the use of popular forms

of digital media and compares it with traditional

media. There are different potential criteria to build a

typology of digital media, for an extensive review see

(Salaverría, 2017).

The focus of Figure 2 is on media whose content

is generated by humans, like online press. Currently,

software agents, often called bots, strongly gain in

importance for all primary media functions

mentioned above. They can be embedded in other

software, act invisibly to human users, and create,

arrange, and transfer communication content

automatically without human intervention. Further

types of communication content generated by

machines are performance and vital data in the field

of self-monitoring captured by sensors (Petrovic,

2017b) or results of search engines and recommender

systems. All these examples support the notion that

digital media is used for communication between

machines and humans..

Figure 2: Daily media consumption in hours, n=153.501,

age 16-64, 36 countries around the world (source:

globalwebindex 2017). Other online activities like

browsing and e-commerce not included.

4 FINDINGS FROM THE FIELD

4.1 Research Question

The main aim of the present study is to better

understand the alteration mechanism of digital media

for informal learning. This broadened understanding

can help improve practice of informal learning by

learners as methods of teaching, and to envision and

design new learning environments. Therefore, the

research question is: What are digital media’s

alteration mechanism for informal learning? It’s not

the aim to find representative results for a certain

population or to evaluate a certain technical system.

Thus, the methodology applied is selected by its

added value to gain insights into digital media’s

alteration mechanism on learning and not its

02:23

00:36

01:05

01:59

00:51

00:51

00:46

01:05

TV

Press

Radio

Social Netw.

Games

Online TV

Online Press

Online Radio

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

324

representativeness for a certain population, as is often

the goal of quantitative methods.

4.2 Methodology

The methodology used for capturing learning

episodes in the field by learners themselves in form

of video, pictures, and annotations is based on

autovideography and photovoice (Goo Kuratani and

Lai, 2011; Woodgate, Zurba and Tennent, 2017;

Wang and Burris, 1997). Additional learning

episodes are captured by the author using

participatory action research (PAR) in extensive field

studies, also applying videography. To analyze those

data qualitative content analysis and grounded theory

(Charmaz, 2014) is applied. Subsequently to ten years

of preceding studies with several hundreds of

participants as shown in (Petrovic, 2017a) 50 learners

in two master courses grouped into 10 teams were

asked to capture real-life informal learning episodes

with their own smartphones in form of pictures,

videos, and text annotations and to send them to a

blog for immediate sharing with other participants of

the study. Previously, the main characteristics of

informal learning and different learning domains

were presented and discussed and the learners

received the task to study basic literature on both

topics. Also, the aims, the methodology, and the

procedure of the study were presented and discussed.

After capturing and analyzing the learning episodes

they were presented to the research team. Both, the

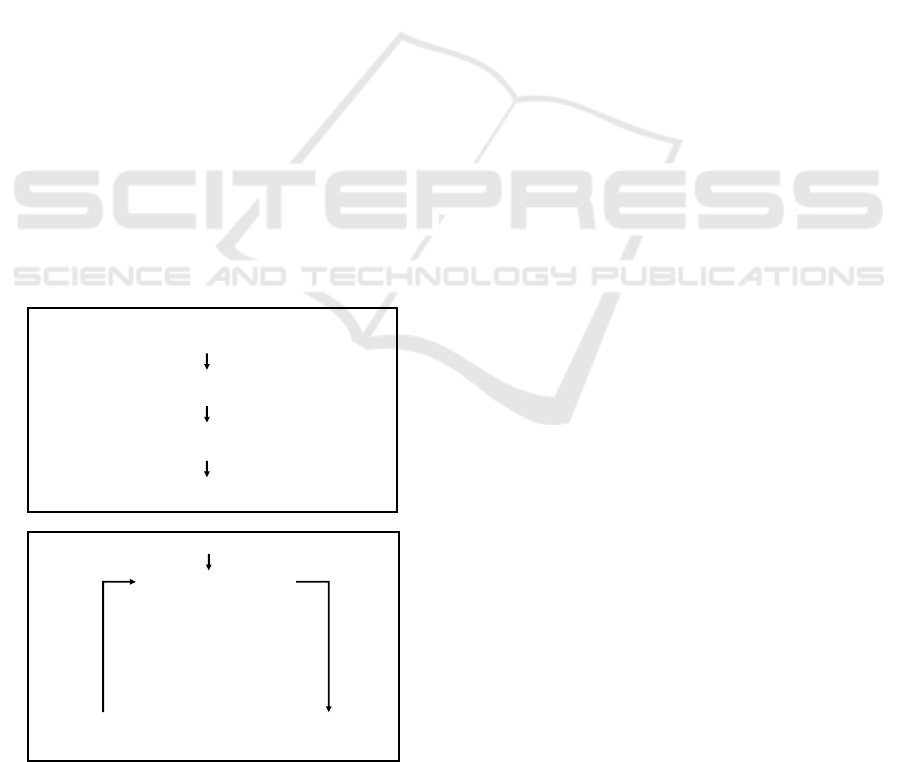

Figure 3: Methodology used to gain insights into digital

media’s alteration mechanism.

captured material in form of pictures, videos, and

annotations as well as the analysis by the learners

themselves represented the input data for the research

team. Additionally, the research team also captured

some learning episodes to fill gaps in data for certain

learning domains as mentioned by learners such as ‘I

have liked to capture …’ (see Figure 1 for an

example).

The whole analyzing process of the learning

episodes was performed with the software

MAXQDA. The first step of the research analysis was

to assign the learning episodes or certain parts of them

to one or more learning domains. For this, the

learning episodes were analyzed according to the

main characteristics of cognitive, affective, and

psychomotor learning. If single parts of the learning

episode were related to different learning domains,

those parts were marked and assigned within

MAXQDA separately. The second step was to

analyze the learning episodes once with the ‘glasses’

of objectivist and in a second run with those of a

constructivist point of view together with their related

learning theories. The focus of that analysis was to

identify alteration mechanism of digital media in the

three different learning domains. As a starting point,

the identified alteration mechanisms were

categorized based on a tentative category system

deduced from theoretical concepts. According to the

methodological approach of qualitative content

analysis and grounded theory the category system

was further developed iteratively during the process

of analysis. Same or similar alteration mechanism

where grouped together and groups of mechanism

were assigned to main groups. During this process,

the research team looked out for coherent

mechanisms, plausible relations between them, and

aimed to reach an exhaustive category system. The

main guideline during the whole analysis was the

additional value of categories concerning the research

questions.

4.3 Findings

Table 1 shows digital media’s core alteration

mechanism for informal learning as found after

several iterative cycles between analyzing and

categorizing captured learning episodes on the one

hand, and theoretical views from learning theory and

epistemology on different learning domains on the

other hand. This categorization is neither exhaustive

nor mutually exclusive. In traditional media like

printed newspaper the three domains of create and

delete, arrange and link, and transmit and access to

a great extent form a linear step-by-step sequence of

Intro in digital media, informal learning,

learning domains, methodology used

Individual capturing learning episodes in form of

videos, pictures, annotations

In teams: selecting most informative episodes,

analysis, and presentation

Learning episodes and learner’s analysis

as input data

Writing initial category system based on theoretical concepts

Refined category system

Analyzing and coding learning episodes

R

e

s

e

a

r

c

h

p

r

o

b

l

e

m

o

r

i

e

n

t

e

d

s

e

l

e

c

t

i

o

n

a

n

d

a

n

a

l

y

s

e

s

R

e

e

x

a

m

i

n

a

t

i

o

n

o

f

e

a

r

l

i

e

r

d

a

t

a

Assigning and grouping memos

and codes

Raising codes to tentative

categories

C

o

n

t

e

n

t

a

n

a

l

y

s

i

s

/

g

r

o

u

n

d

e

d

t

h

e

o

r

y

P

h

o

t

o

v

o

i

c

e

Data capturing

Data analysis

Digital Media’s Alteration Mechanism for Informal Learning

325

activities, ranging from writing an article by an editor

to reading the newspaper by the reader. In a

perception sphere including digital media this is not

the case. An activity in one domain immediately

triggers mechanism in another one, whereas this

alteration initiates further mechanism.

Simultaneously, one communication activity is

mostly impacted by different related alteration

mechanisms at the same time. The resulting

interdependent communication contents form the

perception sphere. Communication content is not

only created by humans or machines explicitly in

form of dedicated entities, but also by arranging and

linking them and the dynamics of its structure. A

certain browsing behavior creates a new perspective

on communication content and thus, it leads to altered

content within the perception sphere. Relations

between content in form of spatial proximity like

search results or semantical proximity due to linking

create new content and become important parts of the

perception sphere. Also, the behavior in accessing

creates new content, e.g. due to traced user behavior

and deduced recommendations such as ‘most read’ or

‘other users also looked at …’.

The alteration mechanisms in Table 1 are enabling

factors for higher degree of freedom in shaping

content nodes and relationships within a perception

sphere where informal learning happens. They

shouldn’t be seen as totally new capabilities or as

inevitable improvement or deterioration of informal

learning due to the advent of digital media.

Table 1: Digital media’s alteration mechanisms for

informal learning.

Domain of alteration

mechanism

Alteration mechanism

Create and delete

1. Medialization

2. Omnipresent means of

production

3. Real time reach

4. Copy-ability without loss and

marginal costs

5. Traceability

6. No doubtlessness of deletion

Arrange and link

1. Divisibility

2. Multi-perspectivity

3. Associativity

Transmit and access

1. Efficient transmission

2. Immediacy

3. Searchability

4. Interactivity and Contingency

5. Ubiquity

4.3.1 Create and Delete

Medialization means the representation of a certain

communication content via a digital media instead of

by the physical environment. A learning episode

found in the psychomotor domain was playing tennis

with Nintendo’s Wii in front of a screen instead of on

a physical tennis court. This medialization leads to a

medial difference (Pietraß, 2016) between the

physical environment and the learning environment

including digital media. Therefore, the learning

environment doesn’t represent the physical

environment but becomes a new perception sphere

with its own information content, linkage, forms of

access (swinging the virtual tennis racket), and social

rules. For the learner, it is ‘reality’ like playing on the

court, but a different one. From a constructivist point

of view, both realities are created by the learner

himself. Nintendo’s game designers have that in mind

and don’t try to imitate the physical game perfectly

but exploit digital media’s alteration mechanism. A

further lucid learning episode found was remote

control a flying drone. The medial difference to a

human which cannot fly is so big that together with

the alteration mechanism of multi-perspectivity

sustained affective learning is stimulated, particularly

considering values and norms. Informal learning

happens more and more in environments which are

created by humans and machines instead by evolution

respectively God’s design.

Traditional media requires rare and expensive

means of production like presses, broadcasting

stations, and complex logistic systems. Means of

production of digital media are omnipresent in form

Figure 4: Tracing a bike ride opens informal learning

opportunities on local history, culture and geographic.

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

326

of smartphones, personal computers, computerized

things of daily life, and the Internet. The ubiquitous

use of digital media leads to continuous informal

learning, largely independently from intentions,

structures, and activities of the formal education

system and its teachers. That means, that learning

happens more and more independent from traditional

authorities like parents, teachers, or publishers.

Digital media’s omnipresence together with its

efficient transmission of communication content

leads to an increase in real time reach. For example,

immediately after writing a blog post it can be read

by thousands and millions of other people as well as

by machine based agents. This works similarly for

real time sharing of performance and vital data on

fitness platforms as shown in Figure 1. No layouting,

printing, physical distribution, and scanning to make

the content readable by machines is necessary.

Therefore, informal learning can utilize more content

with promptness as core value. At the same time, also

the critical analysis and embedding in one’s own

point of view, often seen as the opposite of

promptness, can lead to informal learning processes

based on digital media. Both promptness and in-depth

analysis happen in the learning episode shown in

Figure 1. Informal learning gains more degrees of

freedom by combining different alteration

mechanisms and doesn’t solely suffer changes

induced by digital media.

While creating communication content, it can be

copied without loss in quality, with no or extremely

low marginal cost, and without much time needed.

This Copy-ability leads to a significant increase in

content in form of text, pictures, video, and linkages

between them, and consequently leads to a strongly

extended perception sphere for informal learning.

Growing demands concerning learning in the

affective domain is a consequence for learning,

particularly in the field of receiving including

awareness and willingness to hear and give attention

to a certain issue. This alteration mechanism could be

a fruitful connecting point between informal learning

and formal settings with teachers – not only by

‘teaching’ media literacy but mainly by building a

scaffold to learn informally in the fields of awareness

and willingness during daily life behavior.

Traceability is mostly seen as an alteration

mechanism for the domain of transmission and

access. But it also strongly alters the creation of

content. Every activity with digital media is traced,

whether someone wants that or not – otherwise digital

media wouldn’t work technically. Google’s organic

search results as important communication content

are strongly based on the search behavior of humans

and machines. Tracing user behavior enables

recommendations on e-commerce sites as

personalized news feeds. Whereas the tracing is

always done by machines, its object can be the

behavior of humans, for example clicking patterns, or

of machines, such as web crawlers which generate

around a third of the Internet traffic. The results of

tracing can be analyzed and used by humans or

automatically by machines like the personalized

arrangement of content by Facebook, which

permanently creates new content. The consequence of

that alteration mechanism for informal learning is

more communications content on the one hand and an

increased richness of it on the other hand. As shown

in Figure 4, tracing vital and performance data from

one’s own bike ride or from live tracking shared by

peers on platforms like Strava, Garmin Connect, or

Komoot opens possibilities for informal learning on

geographic characteristics of the environment,

recommended sightseeing opportunities, or historical

and cultural insights into cities along the route. This

alteration mechanism can bridge psychomotor

activities with informal learning within the cognitive

and affective domain.

The alteration mechanisms of copy-ability,

efficient transmission, and real time reach lead to no

doubtlessness of deletion. Immediately after its

creation, the communication content can be

disseminated widely within the whole Internet and

other networks with or without human intervention.

Due to the impossibility of knowing the number of

indistinguishable copies of certain content and their

current storage location, it’s hard to imagine that

somebody can guarantee the full removal of certain

communication content. That is the root of the

discussion on ‘the right to be forgotten’, started by

Mayer-Schönberger (2011) and that was taken up by

the European Commission. This alteration

mechanism expands possibilities for informal

learning as it extends the perception sphere with

content, which otherwise would be deleted or

disappeared. On the other hand, it can also inhibit

learner’s willingness to share opinions and personal

data, and thus, also opportunities for one’s own and

other’s informal learning shrink.

4.3.2 Arrange and Link

Divisibility offers the possibility to split

communication content into any number of packages

for re-arranging and separate sharing. A widespread

example is play lists for audio and video files. This

alteration mechanism can be directly led back to

technical implications of digitalization, specifically

Digital Media’s Alteration Mechanism for Informal Learning

327

discretization of signals. It facilitates micro learning,

using small packages of learning content ‘on-

demand’, e.g. while using a certain software product.

These packages are context sensitive and

personalized taking into account the learner’s actual

need in real time – often resulting from a quick

Google search. Consequently, en passant micro

learning in the sense of informal learning increasingly

replaces formal learning in traditional seminars on

using certain software.

Multi-perspectivity allows the arrangement of

communication content, or certain parts of it, in

spatial proximity to other content. Because of this

changed context, the content gain added value which

can be used for informal learning. An example is

displaying blog posts arranged by author, date, certain

predefined topics, or tags. In a broader sense, also

individual browsing after querying a search engine

creates a unique perspective on existing content. It’s

unlikely that another user searching for the same item

in the same content will apply the same browsing

sequence. Thus, every user generates its own

perspective depending on its clicking and browsing

behavior. That multi-perspectivity results in

alterations in the cognitive learning domain, for

example by finding different applications of a certain

mathematical formula. Therefore, the learner can gain

a deeper understanding and can bring his knowledge

from the low level of recalling the formula to

applying it for different problems.

Associativity is best known by hyperlinks

embedded in communication content and by

recommender systems. Because of this embedding,

the content itself changes and gains a new quality.

This alteration mechanism is closely related to multi-

perspectivity and both are core building blocks of

digital media’s alteration mechanism for informal

learning. It not only leads to alterations in the

cognitive learning domain as shown in the example

above, but also in the affective learning domain.

Associativity helps the learner to explore

communication content triggered by a sudden

perception, desire, emotion, or just by chance. Thus,

he can gain awareness for a new issue, explore it

immediately, and induce different valuing of a certain

domain. For example, someone hears streamed music

from a certain musician on a Tablet or PC, learns that

the artist changed his name several years ago,

searches in Google to find out why, and ends up

reading about a different religion largely unknown to

him so far. At the same time, this is an example for

wander off the point caused by associativity and how

hard it can be to stay attentive and concentrated on

what you are doing at the moment. Thus, we speak in

this study of ‘alterations’ and not ‘improvements’ for

informal learning.

The alteration mechanism of arrange and link

facilitates the shift from a mostly linear, self-

contained content like a book or a movie to a

multidimensional and open perception sphere.

Therefore, associativity is probably the most

important alteration mechanism for informal

learning.

From the perspective of social systems theory,

that perception sphere is an autopoietic system,

characterized by a high level of contingency

(Luhmann, 1996). Its participants are not only

humans but also machines controlled by algorithm,

equipped with self-learning capabilities based on

artificial intelligence. In those algorithms

functionalities are embedded that are similar to

learning in the affective domain, making changes in

giving attention to a certain issue, for example by an

adapted search strategy. Examples for alterations in

responding are automatic generated Likes or blog

posts, and highly personalized intelligent agents for

changing habitual behavior. Currently, those

algorithms try to catch up to human intelligence

which is ‘strong’ particularly because of three

capabilities: defining its own problem to be solved,

specifying and adapting the problem-solving

algorithm by itself, and modifying hardware during

the process of problem solving, like changes in

synapses of the human brain. When machines and its

embedded algorithm achieve that goal and its

algorithm are no longer programmed by humans but

by machines themselves, the point of Singularity is

reached (Kurzweil, 2005).

4.3.3 Transmit and Access

Efficient transmission as an alteration mechanism is

widely discussed and facilitates the transmission of

more communication content, without loss of quality,

and with no or very low time delay and marginal costs

for half of mankind. It’s also discussed

comprehensively from a theoretical point of view,

like in economic theories including transaction cost

and principal agent theory. It has its origin directly in

the technical capabilities of digitalization and is the

basis for other alteration mechanism. Therefore, its

alterations for informal learning are discussed in

connection with other mechanisms.

Immediacy is the counterpart to the alteration

mechanism of real time reach as discussed above in

the section on the domain ‘create and delete’. The

time lag between the creation of a certain

communication content and learner’s awareness for it

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

328

shrinks or disappears entirely. More and more content

with high promptness become available. Because of

disintermediation of intermediaries like journalists,

publishers, or teachers also authenticity of

communication content can increase. For a fruitful

use of that authenticity in relation with a strongly

increased quantity of communication content,

competencies out of the affective domain like

awareness, giving attention, responding, valuing, and

organizing must be further developed. This need can

become a valuable trigger for informal learning

processes.

Searchability is mainly based on the alteration

mechanism of medialization, traceability, and

efficient transmission. It facilitates search for a

certain content, relations to other content, for meta

information like author, date and place of creation, or

certain tags. The search can be triggered by humans

or by machines; also the results can be used by both.

Because of the alteration mechanism of efficient

transmission, the search can be done with no or very

little time needed and marginal costs within huge

quantities of communication content. From a

constructivist point of view, search results are not a

characteristic of the underlying communication

content but they are the content. Only the results of

transmit and access can be perceived by humans and

by machines. Therefore, search and access tools are

not neutral means for better use of the perception

sphere; instead they are very significant content

creators within it.

Interactivity is characterized by the relation of

certain communication content to several previous

ones (Rafaeli, 1988). Also, interactivity is enabled

and used by human and machine based participants of

the perception sphere and creates new

communication content within it in relation with the

alteration mechanism of associativity. Contingency

means, that the outcome of a certain interaction is

open in principal (Luhmann, 1996). Thus, it is the

content for learning also. Interactivity and

contingency together with arrange and link create the

most significant alterations for informal learning and

lead to a strong decrease of learning control by

traditional authorities like educators, parents, or

publishers. Simultaneously, for the learner, it creates

numerous new opportunities to construct own

knowledge as core characteristic of learning from a

constructivist point of view.

Ubiquity means, that communication content is

available anytime and everywhere. The perception

sphere for informal learning is no longer limited to

communicating participants like human teachers,

textbooks, natural environment or smartphones and

gaming consoles. It includes more and more everyday

objects like a pair of glasses, watches, refrigerators,

LED Lamps or sensors for vital and performance data

as discussed above in the context of Internet of

Things. As informal learning often happens en

passant during everyday life, ubiquity highlights the

importance, especially for teachers, to look beyond

digital media dedicated developed for learning, like

courseware or distance education.

5 CONCLUSION AND FURTHER

RESEARCH

Digital media extend learners’ perception sphere

strongly, and therefore the opportunities for informal

learning. The discussed alteration mechanisms lead to

everyday life environments with high interactivity

and contingency in contrast to linear, predefined

content mostly used in formal learning settings.

Today, educators have their focus mostly on digital

media supporting their teaching, like courseware or

distance education, turning a blind eye to the main

part of students’ learning – the informal part. To fully

utilize digital media’s alteration mechanism,

educators should neither stick to pure transfer of

knowledge nor retreat to a facilitator role, the latter of

which is empty of content. Utilizing digital media’s

alteration mechanism, he can head for being a

renowned source of knowledge and to focus the

interaction process, introduce appropriate concepts of

the discipline, and help to reach intellectual

convergence. Without this convergence, because of

fully individualized learning styles and contents,

social cohesion will shrink as people can no longer

communicate among each other due to the lack of

mental connectability.

Future research will cover a deeper analysis of

captured learning episodes to further refine and

evaluate the category system of alterations. Also,

capturing learning episodes in additional cultural

areas is planned to better understand differences in

alterations for learning despite a globalized world.

Finally, the alteration mechanism will be deepened on

selected learning domains and digital media, for

example on the affective domain and self-monitoring.

REFERENCES

Ainsworth, H. L. and Eaton, S. (2010) Formal, Non-formal

and Informal Learning in the Sciences. Eaton

International.

Digital Media’s Alteration Mechanism for Informal Learning

329

ARD/ZDF. (2017) Onlinestudie 2017 – Kern-Ergebnisse.

Available at: http://www.ard-zdf-onlinestudie.de/files/

2017/Artikel/Kern-Ergebnisse_ARDZDF-

Onlinestudie_2017.pdf (Accessed 24. November 2017)

Atkinson, S.P. (2014) Adaptation of Dave’s Psychomotor

Domain. Available at: https://spatkinson.

wordpress.com/tag/daves-taxonomy (Accessed 10.

November 2017)

Bloom, B., Englehart, M., Furst, E., Hill, W. and

Krathwohl, D. (1956) Taxonomy of educational

objectives: The classification of educational goals.

Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York, Toronto:

Longmans, Green.

Charmaz, K. (2014) Constructing Grounded Theory: A

Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. SAGE

Publications.

Council of Europe. (2000) Strategies for learning

democratic citizenship. Strasbourg.

Dave, R.H. (1970) ‘Psychomotor levels in Developing and

Writing Behavioral Objectives’ in Armstrong, R.J. (ed.)

Developing and Writing Behavioral Objectives. Tucson

AZ: Educational Innovators Press.

Glasersfeld E. von. (1995) ‘A constructivist approach to

teaching’ in Steffe, L. P. and Gale, J. (ed.)

Constructivism in education. Erlbaum: Hillsdale: pp. 3–

15.

Goo Kuratani, D.L. & Lai E. (2011) TEAM Lab -

Photovoice Literature Review. Available at:

http://teamlab.usc.edu/Photovoice%20Literature%20R

eview%20(FINAL).pdf (Accessed 10. November

2017)

Harasim, L. (2017). Learning Theory and Online

Technologies. Taylor and Francis. Kindle-Version.

Harring, M., Witte, M. and Burger, T. (eds.) (2016)

Handbuch informelles Lernen – Interdisziplinäre und

internationale Perspektiven. Weinheim und Basel:

Beltz.

International Telecommunication Union (2016) ICT Facts

and Figures 2016. Available at: https://

www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Documents/facts/

ICTFactsFigures2016.pdf (Accessed 2. November

2017)

Keil-Slawik, R., and Selke, H. (1998) ‘Forschungsstand

und Forschungsperspektiven zum virtuellen Lernen von

Erwachsenen’ in: Arbeitsgemeinschaft Qualifikations-

Entwicklungs-Management Berlin (eds.).

Kompetenzentwicklung ´98 – Forschungsstand und

Forschungsperspektiven. Mnster: Waxmann-Verlag,

pp. 165–208.

Krathwohl, D. R., Bloom, B. S., & Masia, B. B. (1973)

Taxonomy of educational objectives, the Classification

of educational goals. Handbook II: Affective domain.

New York: David McKay Co., Inc.

Krathwohl, D.R. ‘A Revision of Bloom's Taxonomy: An

Overview’, THEORY INTO PRACTICE, Autumn 2002,

p. 212-218.

Kurzweil, R. (2005) The Singularity Is Near: When

Humans Transcend Biology. Viking.

Luhmann, N. (1996) Social Systems. Translated by

Bednarz, J. Jr. with Baecker, D. Stanford University

Press.

Mayer-Schönberger, V. (2011) Delete: The Virtue of

Forgetting in the Digital Age. Princeton Univers. Press.

Petrovic, O. (2017a) ‘D-Move: Ten Years of Experience

with a Learning Environment for Digital Natives’ in:

Proceedings of the 9th International Conference of

Computer Supported Education, Porto 21.-23. April

2017, p. 315-322.

Petrovic, Otto (2017b) ‘Self-monitoring: A Digital Natives’

Delphi Embedded in Their Everyday Life’ in:

Proceedings of the 4th European Conference on Social

Media, Lithuania 3.–4. July 2017.

Petrovic, O. (2017c) ‘The Internet of Things as Disruptive

Innovation for the Advertising Ecosystem’. in: Siegert,

G., von Rimscha, M.B. and Grubenmann S. (ed.)

Commercial Communication in the Digital Age.

Information or Disinformation?, Berlin/New York: de

Gruyter.

Pietraß, M. (2016) ‘Informelles Lernen in der

Medienpädagogik’ in: Rohs M. (ed.) Handbuch

Informelles Lernen. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, p. 123-

142.

Rafaeli, S. (1988) ‘Interactivity: From new media to

communication’ in Hawkins, R.P., Wiemann, J.M. and

Pingree S. (eds.) Sage Annual Review of

Communication Research: Advancing Communication

Science: Merging Mass and Interpersonal Processes,

16, Beverly Hills, p. 110-134.

Salaverría, R. (2017) ‘Typology of Digital News Media:

Theoretical Bases for their Classification’.

Mediterranean Journal of Communication, 8(1), p. 19-

32.

Selke, H. (2008) Sekundäre Medienfunktionen fr die

Konzeption von Lernplattformen fr die Präsenzlehre,

Dissertation, Paderborn.

Wang C., and Burris M.A. (1997) ‘Photovoice: Concept,

Methodology, and Use for Participatory Needs

Assessment’ Health Education & Behavior, 24(3), p.

369–387.

Woodgate, R.L., Zurba M. and Tennent P. (2017) ‘Worth a

Thousand Words? Advantages, Challenges and

Opportunities in Working with Photovoice as a

Qualitative Research Method with Youth and their

Families’. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18 (1).

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

330