Aspects of User Experience Maturity Evolution of Small and Medium

Organizations in Brazil

Angela Lima Peres

1

and Alex Sandro Gomes

2

1

Universidade de Ciências da Saúde de Alagoas, Maceió, Brazil

2

Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil

Keywords: User Experience Design, Maturity Models, SME.

Abstract: This paper investigates aspects of evolution of user experience design practices in small and medium

Brazilian organizations and the relation to dimensions of User Experience Maturity Models. A qualitative

approach was carried out. Eight user experience managers or analysts were asked about the evolution

process of incorporate User Experience practices and strategies adopted to deal with the limitations of small

and medium software organizations. A semi-structured interview script was developed specifically for this

study. Data collection was carried out through interviews with the Skype® tool, and qualitative analysis was

performed with the aid of MAXQDA® software. Through content analysis, the study presents and discusses

the strategies adopted by eight User Experience designers and the relation to dimensions of User Experience

Maturity Models. The difficulties faced by small and medium organizations are discussed, and some

alternatives that are adapted to small budgets and human resources are presented.

1 INTRODUCTION

Maturity Models provide an evolutionary path which

continuously defines, maintains, and optimizes

design processes and products (SEI, 2010). They

consist of the best practices adopted and validated

by the market and the academy (SEI, 2010).

Maturity models have been proposed for user

experience design (UX) (Earthy, 1998; Earthy,

Jones, Bevan, 2001; Jokela, 2010; Nielsen, 2006;

Nielsen, 2006b; Gonçalves, Oliveira, Kolski, 2017;

Lacerda, Wangenheim, 2017).

Important global example was created by the

organization known as the Human Factors Institute

(Schaffer, 2004; Schaffer, Lahiri, 2014).

However, small and medium companies (SME)

have difficulties in implementing maturity models,

related to budget, human resources availability, and

training, to mention some aspects (Dyba, 2003;

Mishra and Mishra, 2009; Pino, Garcia, Piattini,

2008).

Thus, the following questions have become

relevant: how has been made the evolution of user

experience maturity of small and medium

companies? How the current practice relates to the

dimensions proposed in the UX Maturity models?

Few studies have addressed these issues, and as

such, the present paper could be useful to small and

medium organizations (SME) that wish to improve

their user experience processes.

This article studies the strategies to evolve

maturity of practices related to user experience

design in small and medium organizations at Brazil

and associates with the dimensions proposed in the

maturity models for user experience design.

The article is structured as follows: section two

details the methods used in the research; third

section details the strategies adopted by

organizations and the relation with the UX Maturity

Models; final section presents the conclusions.

2 METHODS

Qualitative methods have been used increasingly in

the area of software engineering since human

aspects are very significant, especially in the study,

implementation, and evaluation of process studies in

the development of software. Authors report that the

adoption of this paradigm can offer richer

information and results when it comes to variables

such as motivation, perception, justifications, and

Lima Peres, A. and Sandro Gomes, A.

Aspects of User Experience Maturity Evolution of Small and Medium Organizations in Brazil.

DOI: 10.5220/0006801905590568

In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2018), pages 559-568

ISBN: 978-989-758-298-1

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

559

analysis of the choices made (Kitchenham et al.,

2007).

They have been adopted in research in which the

deepening of the understanding of phenomena in

their natural context is an important factor in the

analysis of the results (Merriam, 2009).

2.1 Profile of Respondents

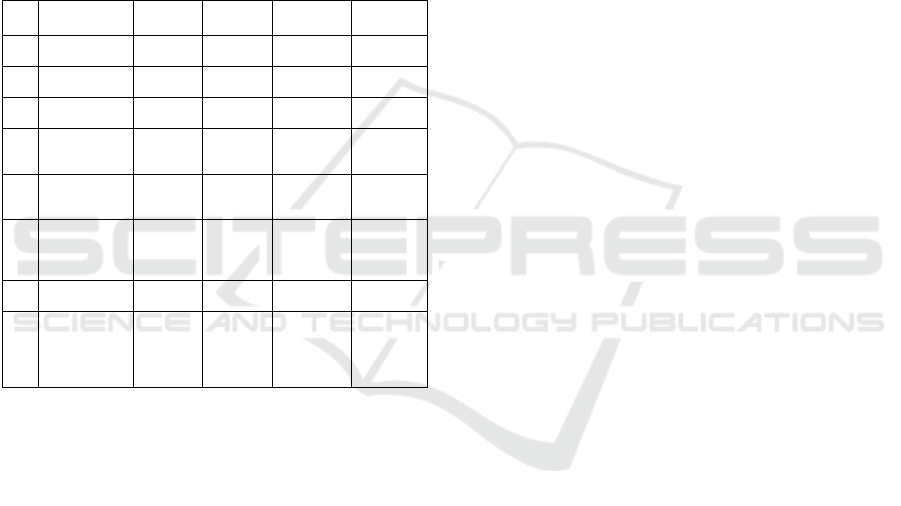

Table 1 contains a consolidated view of the profile

of the eight respondents. Aspects regarding the

training, interviewees' experience, roles and quality

certification in the software development process are

reported in the table.

Table 1: Profile of respondents.

ID Education

Project

Manager

Experience

UX

Experience

Role Certification

P1 Graduation Np

6-10

y

ears

Visual

Desi

g

ner

ISO 9001

P2 Doctorate

2-5

y

ears

6-10

y

ears

Project

Mana

g

er

ISO 9001

P3 Specialization Np

6-10

y

ears

UX

Desi

g

ner

-

P4 Master

>15

years

< 2 years

TI

Manager

MPS.Br

(MR-

MPS-SW

)

P5 Master Np

6-10

years

PO, UX

Designer,

Researcher

-

P6 Master

11-15

years

2-5

years

TI

Manager,

UX

Mana

g

er

ISO9001

P7 Specialization

6-10

y

ears

6-10

y

ears

UX

Desi

g

ner

ISO9001

P8 Specialization

6-10

years

6-10

years

UX

Designer

and

Project

Leader

ISO14001

2.2 Data Collection

The main collection instrument chosen consisted of

an interview whose script is in appendix. The choice

of sample was intentional, composed by eight

professionals with consistent experience at UX in

small and medium-sized organizations.

Interviews are relevant instruments of collection

and analysis in qualitative research since they allow

to deepen the aspects that are the object of

investigation (Kitchenham et al., 2007; Merriam,

2009).

During the previous stage of selection of the

respondents' sample, seventy-two managers and

analysts participated and answered a questionnaire

where it was possible to understand the profile of the

area.

The invitations were sent to email lists of human-

computer interaction groups, designers and

professors, researchers, speakers and managers in

the area of information technology. The

questionnaire was opened in the period from

November 24, 2015 to January 10, 2016. Twenty-

four answered the survey completely.

The questionnaires were elaborated and made

available on the web, through the Surveymonkey®

tool that allows to prepare, publish and collect the

answers obtained. The tool also allows the

monitoring of the answers and assists in the

consolidation and statistical analysis, when

necessary.

The choice of sample was intentional. After the

analysis of the profile of the respondents of the 1st

stage, eight respondents were chosen by the

researcher and through the indication of their peers.

Only active representatives from the agile and

design communities were selected.

The non-random sample is indicated in

qualitative research since respondents or

interviewees are selected to deepen the phenomenon

being investigated (Merriam, 2009). Li, Smidts

(2003) and Garcia (2010) reinforce the importance

of selecting specialists in the field to study strategies

for improvement in software development processes

where there is a great diversity of scenarios and

variables to be analysed.

The interviews were performed using the

Skype® tool with the help of the complementary

recording tool, Callnote® (CALLNOTE), to

facilitate transcription and analysis. A pilot to

evaluate the collection instrument was conducted

with a professional with more than six years of

experience in UX in which the understanding of the

purpose of the research, of each question and the

time required for the answers were analysed and

adjusted.

The interviews were recorded with the prior

consent of the interviewee.

The semi-structured interview script was used so

that the researcher could create opportunities for

discoveries during the interview process and as a

checklist of possible gaps to be explored.

Further information on the analysis step will be

described in the following sections.

2.3 Data Analysis

The recordings were transcribed using the

MAXQDA® tool. They were, however, transcribed

without the aid of other complementary software, to

enhance the researcher's understanding of the

material collected.

MAXQDA® software was used for analysis.

This allows the information collected through the

ICEIS 2018 - 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

560

questionnaires, annotations and recorded audios to

be stored, coded, allowing the analysis to be

deepened (MAXQDA).

The results and analysis contemplate research

questions about the adoption of the dimensions

suggested in the literature, in the organizations and

projects in which they operate. The justifications for

adopting or not adopting the importance of these

dimensions were also investigated, given the

respondents, benefits, and limitations when referring

to small and medium-sized organizations.

For the qualitative analysis, we used the analysis

of themes identifying patterns in the answers that

allowed to deepen the diagnosis of the scenarios of

adoption of the practices. For this, the following

phases adapted from Boyatzis (1998) were

developed:

Transcript of comments and open replies to

create familiarity with the data and deepen the

understanding of the content;

Generation of codes that could segment the

main findings of the research;

Refinement of these initial codes by grouping

them into new key categories when necessary;

Organization of each category for relevant

information, analysing possible correlations;

Analysis of the findings, try to discover

associations with the literature and generating

hypotheses to be investigated;

Additional investigations with the respondents

in the hypotheses raised.

The data grouped into the categories were organized

in MaxQDA® software, observing the several

correlations being studied. The names of the

categories were identified based on the researcher's

questions about the findings that had been identified

in the literature and on questions that arose when

analysing interviewees' responses from the previous

collection stage through the questionnaires and the

interviews stage (Merriam, 2009).

The results and discussions will be presented in

the following section.

3 RESULTS

The dimensions proposed by the maturity model for

user experience design recommended by the Human

Factors Institute includes: the formalization of the

development process with the integration of user

experience design practices in the development

cycle; the training of the professionals involved; the

establishment of patterns of corporate design; the

establishment, collection and monitoring of metrics

to assess the usability of the software; the creation of

a database of successful cases for training purposes,

thereby showing the value of user experience design

in the organization; effective joint actions at the

highest decision-making levels in order to obtain

resources dedicated to the practices of user

experience (Schaffer, 2004; Schaffer, Lahiri, 2014).

These dimensions are also presented in other

maturity models such as Nielsen (2006) and Nielsen

(2006a).

This study investigates the alignment of these

dimensions with the process of evolution of UX

integration on development cycle of small and

medium organizations of respondents.

This study analyses the adoption of practices and

observes similarities, differences, limitations and

potential opportunities for improvement about the

literature study.

The main categories were identified based on the

dimensions that had been identified in the UX

Maturity Models studied in literature. The other

categories and subcategories arose when analysing

interviewees' responses through the interviews stage

(Merriam, 2009).

The analyses carried out according to the main

categories generated with the aid of MAXQDA®

software will be presented below.

3.1 Support to UX Practices

Schaffer and Lahiri (2014) indicate that institutions

should adopt the practice of defining sponsoring

executives (called UX champions) that support

institutionalization initiatives in user experience

design practices.

These managers can provide more investment in

people, evangelizations, training, acquisition of

tools, an organization of physical space, equipment

and in the incentive to UX practices.

However, participants in this research report that

in their organizations, the importance of UX is still

not recognized by top management.

This fact impacts on restrictions to the full

exercise of UX practices in many projects in which

they are involved. Or they often do not allow them

to get involved in some other projects being

undertaken by information technology teams.

P1, P3, P7, and P8 mention that even when

working in medium to large sized companies, where

top management recognizes UX as an essential

practice, this awareness does not translate into

investments. This impact that the team can be

involved in the various projects of the company at

Aspects of User Experience Maturity Evolution of Small and Medium Organizations in Brazil

561

the same time.

All interviewees report that in their

organizations, the number of UX professionals is

minimal compared to what they see as ideal.

Often, only one professional is dedicated to more

than just one project at a time, and they have to

choose between the various initiatives, even though

others would need research, ideation, prototyping

and testing, and that it will not be possible to do it

due to lack of resources.

In a more prominent case, it was reported that the

company even had only one UX pro for 300

developers.

P1, P3, P7, P8 report that the number of highly

reduced UX professionals makes essential tasks

difficult, for example: to include the UX team from

the initial proposal phases, to perform UX searches

and user tests on several of the projects

implemented.

Reduced time allows only interaction design

tasks to be performed, or even just small adjustments

to the interface of perceived aspects that are most

critical to usability, but without research, without

tests that prove that the modifications will be

successful.

P24 mentions that he experienced different

phases in his organization, where the board's profile

regarding the importance of UX was decisive for

increasing or reducing investments in teams, spaces,

and physical resources.

P1, P2, P3, P7 mention that it is rare for top

management to know the activities or techniques of

UX, but even if they do not know how to implement,

the value of practices is imperative for investments

to be made.

When asked how then is it done to motivate UX

practice, when top management is not aware of the

value of these methods, respondents reported that

there are some ways to gain the maturity gain in UX

practice gradually.

These include:

Involvement of middle management, who by

acting closer to the team, can bridge the gap with top

management and can influence other team

components such as developers, testers, and even

customers and end users to collaborate with

practices;

This middle management may sometimes be the

role of project manager or product owner of the

application, and in this case, the above can happen

even more efficiently, since these roles are decisive

in the planning of the practices to be carried out and

prioritized in the projects;

When the team empowers and begins to show valid

results, developing a solution that can be a feature or

a product, where greater satisfaction, efficiency, and

effectiveness in the user interaction experience with

the product is observed, this can influence other

members of the team. This fact also may even reach

top management, which tends, when perceiving the

impact on user satisfaction, to multiply these

practices in other projects or initiatives that involve

UX;

When there is a leader in the UX team, a

respected professional in the job market, known for

his performance in other projects and who has a

good interface with top management, can influence

the team to carry out these practices;

However, P3 mentions that there is no guarantee

that the institutionalization of practices will be done.

Even if the aspects mentioned in the previous items

are proven, processes are difficult to establish in a

top-down and immediate way, it is I need a time for

maturation, an understanding by every team of the

practices and contexts in which they apply.

Especially if we think of the diversity that is the

ecosystem of applications, tools, and techniques

available in information technology.

P1, P2, and P3 point out that UX practices are

more frequent when executing projects for

companies where the user experience, in the view of

the client contracting the project, is recognized as a

product differential.

They complement, however, that in most of the

projects carried out, the organizations attest to

having no budget or time for inclusion of UX teams

and practices.

3.2 Infrastructure

The dedication of resources to the design of

experience has also been pointed out in the literature

as one of the critical success factors for

institutionalization, that is, the practice of practices

consistently (Schaffer, 2004; Schaffer, Lahiri, 2014).

Recent research on the UX professional profile

reinforces that in Brazil there is an increase in the

number of UX professionals dedicated to

development projects (Vieira, 2011).

However, as evidenced in the interviews and

discussed in the previous topic, this hardware,

software and peopleware’ resources are not yet

planned with medium- and long-term goals in the

organizations studied.

ICEIS 2018 - 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

562

3.3 Training

Schaffer and Lahiri (2014) describe that the practice

of training can take several perspectives.

Not only technical aspects but also awareness of

the importance of usability, essential in the initial

stages of institutionalization. It is vital in initiatives

to gain maturity, regardless of the state in which the

organization is.

Salah (2012) also includes training in the

development process, such as training in agile

methodologies and specific frameworks.

The learning of coaching, leadership and

collaboration techniques recommended by Appelo

(2011) can also influence team performance in

facilitating communication between the different

profiles that need to interact with the project.

Technical aspects are also very relevant and can

range from mobile device design standards,

technical standards of accessibility, prototyping

tools, tools and even testing and research techniques,

such as ethnography (Schaffer, 2004; Schaffer,

Lahiri, 2014).

As with improvement initiatives in other areas of

expertise, the empowerment aspect cannot be

overlooked.

Some of the respondents' comments report

problems that could be minimized by continued

training practices.

About the lack of knowledge in UX practices by

developers:

P5 confirms the above understanding that it is

also necessary to carry out training that allows not

only to know the methods and techniques of UX but

also to enable profiles that have very different

academic backgrounds, converse and reconcile

different challenges:

“The dialogue with the various involved in a

project often proves a challenge, given the diverse

backgrounds” [P5].

P4 reinforces that strategies for institutionalizing

UX practices cannot succeed without continuous

training.

P7 discusses that when he started at the company

where he works, one of his first concerns was to

establish a team of UX composed of people who

were interested in the subject, even if they had no

formal roles related to this issue.

Once the group was established and, through

regular discussions, a better organization of their

practices, they began to prioritize workshops and

lectures that could disseminate this knowledge and

give visibility to the team so that UX practices could

be multiplied.

P1 reports that in its organization, it is responsible

for a weekly training program that aims to discuss

and disseminate success stories of projects carried

out internally, as well as discuss innovations such as

Design Thinking.

However, in this aspect too, it has difficulty

because of the lack of time that is allocated to the

professionals who prepare these lectures or

workshops. You do not always get the dates

together.

3.4 Consulting

Nielsen (2006, 2006b), Schaffer, Lahiri (2014)

understand that consulting practice is essential for

the company that intends to institutionalize UX with

more effective results and more controlled costs.

The consultant can help, for example,

evangelization initiatives, establish an organization's

process, diagnose the current situation, select and

train professionals qualified to practices that will be

important for a specific organization. They also help

with procurement of tools, to help conflict

resolutions between departments by understanding

the priorities of deploying practices or solutions of a

product in different ways.

However, this cost cannot always be paid by

companies of a minimal size that also do not have

the human resources that can be dedicated to such

strategies (Dyba, 2003; Mishra and Mishra, 2009;

Pino, Garcia, Piattini, 2008).

P6, in his speech, affirms the importance of a

consultant to manage conflicts of priorities between

sectors. Also, it understands that the consultant

should be responsible for the dissemination of UX,

should focus primarily on maintaining the synergy

between the teams and the importance of each one's

role in the project.

As in the topic where high management

involvement is discussed, respondents say that it is

rare to bring UX consultancies to help

institutionalize practices.

They report that when interested in

understanding how to make improvements of the

UX process in their organizations, they have

resorted to the establishment of communities of

practices where a relevant example are the chapters

of the IXDA in the several Brazilian States.

3.5 Product and Process Metrics

Product and process metrics, related to UX, are not

defined and managed in respondent organizations,

with some exceptions that will be discussed below.

Aspects of User Experience Maturity Evolution of Small and Medium Organizations in Brazil

563

Three key business scenarios were identified during

the survey:

One refers to those user experience designers

working in organizations whose primary

business is the marketing of a product or

product suite developed by the organization

and that their work consists in providing

corrective maintenance or improvements to

the product (s);

In another category are organizations that

develop products for third parties and that the

portfolio of products that can be designed, as

well as the users who will use these products,

can be very diversified domains, to mention

some: education, health, games;

Finally, one last category researches

innovative products for different customers

and often the delivery consists of the results of

the research that will give input to the product

development carried out by the customer who

bought this consultancy or by a third party.

These three scenarios have different needs and

constraints when it comes to measuring the user

experience.

For the first scenario, where the software product

belongs to the company, measuring the experience

can be very beneficial to discover features that

should be deactivated or prioritized in a new release,

even in these scenarios the adoption of metrics is

limited to the respondents.

The reasons that justify non-measurement are

correlated with the factors we have already

mentioned in previous topics, lack of investments in

human resources and UX tools that allow this

practice to be carried out to the satisfaction.

P3 justifies that only with the more consistent

practice of UX practices can we efficiently measure

UX, which still does not occur in its organization.

P1 reports that they have sometimes even come

up with the definition of indicators that compare the

benefits of adopting UX versus non-adoption in their

organization's projects, but this initiative has not

been implemented.

P4, another respondent from the same

organization, defined an indicator of user

participation in the various stages of design from

design to testing, to measure the degree to which the

team practiced user-centred design. However, this

indicator began to measure the degree of

involvement of the client and not the end user.

One of the respondents who is a businesswoman

of a small organization, but who emerged as a start-

up, reports that she has this practice, and that has

evolved in the way measurements are performed in

her corporation:

“Today we measure the engagement of each

feature. We are going through a process of

restructuring the teams; each team will be

responsible for different features of the software;

each team will have its KPIs. Today we review

engagement [of users] weekly and monthly. But

we are changing our process, and we will start to

monitor the KPIs of each feature as well.”

However, the reality for many respondents is similar

to what P11 states:

“We do not have customer satisfaction indicators

specific to UX; the customer satisfaction indicator

refers to the projects as a whole”.

In the other two business scenarios where the

product does not belong to the organization that

develops it, the difficulties are more significant since

it is not market practice, at least at present, that the

project can be extended so that the post-project

fulfilment of interaction requirements.

P2 also mentions the difficulties of pricing this

type of activity.

3.6 Design Knowledge Base

Style guides, templates, patterns, and a design

knowledge base can promote reuse, consistency,

facilitate development, and improve usability.

The knowledge base on the company's design

solutions has as main objective to promote

organizational knowledge through the recording of

success stories, lessons learned and rational design

decision making.

In the literature of frameworks and strategies that

bring proposals for the design of the integrated

experience to agile methodologies, this aspect is not

frequently cited (DaSilva et al., 2011).

However, maturity models, both related to

software development and experience design,

highlight the importance of this practice in

advancing organizational maturity (SEI, 2010;

Schaffer and Lahiri, 2014).

The reuse has impacts on the improvement of the

software development process, reducing costs and

execution time of new projects (Garcia, 2010).

In addition, the structuring of a knowledge base

allows new members to be inserted in the team with

greater productivity and good design practices can

be shared (Schaffer and Lahiri, 2014).

It is a practice, according to the interviewees,

carried out in an incipient way in the organizations

where they work.

ICEIS 2018 - 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

564

P1, P4, P5, P7, P8 attest that the creation of

interview templates, personas, test scripts is

performed by them, but that is not an

institutionalized practice in the organization that

acts. While realizing the importance, the overload of

the designer's tasks prevents him from engaging in

this practice.

The construction of style guides is also done only

when it is possible. Some attest that their use,

however, may be required when customers who hire

them have their own style guides.

P8 believes that, in cases where the developer

owns the product, the brand identity is built. Also,

they also have difficulty, due to lack of investment

of the organization, to devote themselves to the

construction of, for example, standard components

of design to be reused. But, it has interview

templates or user tests that can be used by other

members of your team and would like more time to

devote to this practice.

Success stories are shared through dedicated

training, as P1 had already reported.

P7 cites the use of frameworks such as JIRA®

that help documents containing the entire design

rationale be shared among the team that is involved

in the project and can be consulted after that as

needed.

All emphasize that this practice is not

institutionalized, they perform when it is possible,

and this often means they do not realize on most

projects.

3.7 Roles and Responsibilities

This section analyses the multiple roles and

responsibilities assumed by each member of the

team in small and medium-sized organizations.

In one of the research organizations, the

developers themselves were also designers on many

projects. For, as attested by one of the interviewees,

only one designer was responsible for all the

demand, and there was no way to get involved in the

various projects in progress.

Thus, the specialist profile is very rare in the

companies interviewed, with each member of the

team needing to learn the roles of others to

contribute more to the project.

One aspect that emerged during the interview

phase was the definition of the roles of requirements

analyst, business analyst, and UX researcher. These

are often confused, merged, or defined in different

ways, depending on the organization, the type of

project, and the way UX is perceived by top

management, customers, and others involved in the

project.

P1, for example, reports that in his company a

few months ago the role of UX researcher has

emerged and that, in this way, the inclusion of UX

activities has begun in the initial phases of the

proposal, facilitating that the practices are planned,

and UX teams are better sized. According to him,

this position was formally defined, replacing the

requirements analyst who had a training and skills

more focused on functional and technical aspects.

This process began when we began to realize the

strategic importance of UX in the projects they carry

out in their organization.

But many point out that the user-centred view is

not yet an institutionalized practice, often depending

on the client requesting the project and that

therefore, this role of the experience designer as a

strategic one to define the product to be constructed,

is not very clear in several organizations.

4 CONCLUSIONS

This study investigates the alignment of the UX

Maturity Models dimensions with the process of

evolution of UX practices of Brazilian small and

medium organizations. We analyse the adoption of

practices and observes similarities, differences,

limitations and potential opportunities for

improvement in the literature study. The analysis

was carried out according to the main categories

generated with the aid of MAXQDA® software.

We could verify, through the field study with

eight professionals working in the design of the user

experience, the adoption and importance of practices

that can promote the maturity gain in UX in small

and medium Brazilian companies of information

technology.

The similarities and divergences between the

practices adopted and the proposals presented in the

literature were observed.

The results indicate that small and medium-sized

organizations still face many difficulties related to

the institutionalization of UX practices.

Reduced UX teams prevent designers from being

present in various development initiatives in their

organization. Limited resources also prevent the full

exercise of UX practices.

Essential tasks such as including the UX team

from the early stages of the proposal, performing

UX searches, and testing with users are complicated,

except in isolated initiatives.

Aspects of User Experience Maturity Evolution of Small and Medium Organizations in Brazil

565

Top management is often unaware of the value of

UX practices, which makes it harder to invest in

human resources, physical space as a test lab, and

acquisition of tools.

Interviewees report that the improvements in the

inclusion of practices usually happen when the

project leader or a practitioner experienced in the

methods can, from opportunities that arise in some

projects, show the team the results obtained

regarding satisfaction of the user.

Respondents also say that processes are difficult

to establish in a top-down and immediate way, it

takes time for maturation, understanding by every

team of the practices and contexts in which they

apply. Especially if we think of the diversity that is

the ecosystem of applications, tools, and techniques

in information technology.

As for training, in many ways, they have also

been carried out ad-hoc.

UX-related metrics are not defined and managed

in respondent organizations, with few exceptions.

Some have testified that the creation of interview

templates, personas, test scripts is carried out by

them, but that is still a not frequent practice. While

realizing the importance, the overload of the

designer's tasks prevents him from engaging in this

practice.

However, they do not consider it simple to adopt

strategies for gaining maturity in user experience

design practices. Among the reasons for complexity,

they highlight essential factors recommended in the

literature, such as the importance of the support of

the high executive levels, awareness of the

importance of UX practices, and their strategic value

in making business-related decisions.

REFERENCES

Appelo, J. 2011. Management 3.0: Leading Agile

Developers, Developing Agile Leaders (Addison-

Wesley Signature Series (Cohn)).

Boyatzis, R. 1998. Transforming qualitative information:

thematic analysis and code development. Thousand

Oaks, CA: SAGE.

CALLNOTE® Callnote: video call recorder software.

https://www.kandasoft.com/home/kanda-

apps/callnote-skype-call-recorder/.

Dasilva, T. S.; Martin, A.; Maurer, F.; Silveira, M. S.

2011. User-centered design and agile methods. A

Systematic Review. In AGILE Conference (AGILE

2011), 77- 86.

Dyba, T.: 2003. Factors of Software Process Improvement

Success in Small and Large Organizations: An

Empirical Study in the Scandinavian Context.

Proceedings of the 9th European software engineering

conference (ESEC/FSE’ 03) September 1- 5, Helsinki,

Finland, 148-157.

Earthy J., 1998. Usability maturity model: Human

centredness scale INUSE Project deliverable D 5, 1-

34.

Earthy J., Jones B.S., and Bevan N., 2001. The

improvement of human-centred processes\—facing the

challenge and reaping the benefit of ISO 13407. Int. J.

Hum.-Comput. Stud. 55, 4 ACM, 553-585.

Garcia, V. 2010. RiSE Reference Model for Software

Reuse Adoption in Brazilian Companies. Ph.D. Thesis,

Universidade Federal de Pernambuco.

Gonçalves T. G., Oliveira K. M., Kolski C. 2017.

Identifying HCI Approaches to support CMMI-DEV

for Interactive System Development. Computer

Standards & Interfaces.

Jokela, T. 2010. "Usability maturity models-methods for

developing the user-centeredness of companies" User

Experience Magazine, 9(1).

Kitchenham, B. A., Budgen, D., Brereton, P., Turner, M.,

Charters, S., and Linkman,S. 2007. Large-scale

software engineering questions - expert opinion or

empirical evidence? IET Software, 1(5), 161.

Lacerda, T. C., Wangenheim, C. G. von. 2017. Systematic

literature review of usability capability/maturity

models. Computer Standards & Interfaces.

Li, M. and Smidts, C. 2003. A ranking of software

engineering measures based on expert opinion. IEEE

Transactions on Software Engineering, 29(9), 811–

824.

MAXQDA®. MAXQDA: qualitative data analysis

software. http://www.maxqda.com/.

Merriam, S. E. 2009. Qualitative Research: a guide to

design and implementation. 2nd ed. San Francisco:

Jossey Bass.

Mishra, D. and Mishra. 2009. A. Software Process

Improvement in SMEs: A comparative View.

Computer Science and Information System, 6:1, 112-

140

Nielsen J. 2006. Corporate Usability Maturity: Stages 1-4

(Jakob Nielsen’s Alertbox) http://www.useit.com/

alertbox/maturity.html.

Nielsen J. 2006. Corporate Usability Maturity: Stages 5-8

(Jakob Nielsen’s Alertbox). http://www.useit.com/

alertbox/process_maturity.html.

Pino, F. J., Garcia F. and Piattini M. 2008. Software

process improvement in small and medium software

enterprises: a systematic review.

Software Quality

Control 16, 2, 237-261.

Vieira, A.; Martins, S.; Volpato, E.; Niide, E. 2011. Perfil

do profissional de UX no Brasil - 2a ed. In: 5º

Encontro Brasileiro de Arquitetos de Informação, São

Paulo.

Salah D. and Paige R. 2012. A Framework for the

Integration of Agile Software Development Processes

and User Centered Design (AUCDI). 6th International

Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and

Measurement, Lund, Sweden.

ICEIS 2018 - 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

566

Schaffer, E. 2004. The Institutionalization of Usability: A

step-by-step guide. Addison Wesley: New York.

Schaffer, E., Lahiri, A. 2014. The Institutionalization of

UX: A step-by-step guide to a user experience

practice. Addison Wesley: New York.

SEI, 2010. CMMI for Development, Version 1.3

(CMU/SEI-2010-TR-033) from the Software

Engineering Institute, Carnegie Mellon University

http://www.sei.cmu.edu/library/abstracts/reports/10tr0

33.cfm

SKYPE®. Skype. https://www.skype.com/pt-br/.

Straub K., M. Patel, A. Bublitz, and J. Broch, 2009. The

HFI UX Maturity Survey – 2009. Human Factors

International Inc. 1-24.

APPENDIX

INTERVIEW - EVALUATION OF PRACTICES

Redeem previous experiences with UX / Experience

design/interaction design projects in small or

medium-sized companies and analyse the following

practices:

HIGH MANAGEMENT INVOLVEMENT

It is understood, in this proposal, that the

involvement of the top management propitiates the

valuation of the methods of UX including planning

of hardware resources, software and human

resources, aid in the resolution of conflicts between

departments in the prioritization of requirements,

capacity planning, among other structural practices.

1. How do you evaluate the design of high

management involvement practices in the proposed

strategy? How is this accomplished in the projects

you participated? Were there any obstacles or

difficulties in the projects related to this issue? How

were they solved? In your experience, does this

practice facilitate an improvement in the quality of

the process of including UX practices or would you

adopt other practices to solve the problems

mentioned above? If he would adopt other practices,

what would they be?

RESOURCE PLANNING

It is understood in this proposal that for

improvement in the quality of UX practices, the

planning of resources of hardware, software and

human resources becomes necessary in the phases

before the projects for acquisitions, during the

projects to understand new unforeseen demands, in

the finalization of the projects to evaluate the

improvement points.

2. How do you assess the design of planning

practices regarding equipment infrastructure,

physical spaces, human resources, tools needed by

the project team in the proposed strategy? How is

this accomplished in the projects you participated

in? Were there any obstacles or difficulties in the

projects related to this issue? How were they solved?

In your experience, does this practice facilitate an

improvement in the quality of the process of

including UX practices or would you adopt other

practices to solve the problems mentioned above? If

he would adopt other practices, what would they be?

TRAINING

It is understood in this proposal that for

improvement in the quality of UX practices, the

planning of the team's qualifications is necessary for

the phases before the projects for the execution of

preparatory training, during the projects to manage

the necessary training, at the end of the projects for

evaluation of improvement points.

As for the training practices, these, according to the

literature study, can include several aspects such as:

awareness of the importance of usability, technical

aspects such as mastery of techniques, tools, use of

appropriate artefacts for each context, patterns

related to mobile devices, accessibility,

methodologies, behavioural aspects including

leadership, conflict management and change.

They can be carried out "on-the-job" or through

techniques such as the paired design that allow the

learner to follow the work of a more experienced

professional or "learning shots" - to cultivate within

the project a constant and collaborative learning

culture among members.

3. How do you evaluate the design of practical skills

in the proposed strategy? How is this accomplished

in the projects you participated in? Were there any

obstacles or difficulties in the project related to this

issue? How were they solved? In your experience,

does this practice facilitate an improvement in the

quality of the process of including UX practices or

would you adopt other practices to solve the

problems mentioned above? If he would adopt other

practices, what would they be?

Aspects of User Experience Maturity Evolution of Small and Medium Organizations in Brazil

567

KNOWLEDGE BASE

In this proposal, it is understood that to improve the

quality of UX practices, the construction of a

knowledge base with standards, style guides, success

stories, personas or other artefacts becomes

necessary for reuse, to facilitate the insertion of new

members, to build the organization's knowledge

base. In the phases before the projects, the objectives

can be understood about these aspects, during the

projects to carry out the maintenance of this base or

use it, in the finalization of the projects to evaluate

the improvement points.

4. How do you evaluate the concept of the practices

of reflection, planning, and construction of bases of

artefacts and knowledge (style guides, templates,

patterns, personas, cases of success) in the proposed

strategy? These are aimed at reuse in future projects,

facilitate the insertion of new members, gains of

knowledge in the organization. How is this

accomplished in the projects you participated in?

Were there any obstacles or difficulties in the

projects related to this issue? How were they solved?

In your experience, does this practice facilitate an

improvement in the quality of the process of

including UX practices or would you adopt other

practices to solve the problems mentioned above? If

he would adopt other practices, what would they be?

UX INDICATORS

It is understood in this proposal that for

improvement in the quality of UX practices, it is

necessary to define and monitor UX indicators.

In the initial phases, the goals can be understood

about these aspects, during the projects for

compliance management, in the finalization of

projects for dissemination and evaluation of learning

and improvement points.

Indicators may be associated with: increased

productivity when using the product; reduction in

costs associated with training and / or support;

increase in sales or revenues; reduction of time and

costs when developing the product; reduction of

maintenance costs; increasing the attractiveness and

retention of customers, and improving user

satisfaction when interacting with the product.

In addition to metrics associated with the completion

of each improvement cycle or project undertaken, it

is recommended to adopt strategies to accompany

the customer periodically in order to obtain

continuous information about their experience with

the product.

This monitoring can be done through survey

questionnaires, call centre, analytics, search logs, A /

B tests and usability testing.

5. How do you evaluate the design of planning,

measurement and presentation practices related to

UX in the proposed strategy? How is this

accomplished in the projects you participated in?

Were there any obstacles or difficulties in the

projects related to this issue? How were they solved?

In your experience, does this practice facilitate an

improvement in the quality of the process of

including UX practices or would you adopt other

practices to solve the problems mentioned above? If

he would adopt other practices, what would they be?

CONSULTING

6. How do you evaluate the design of consulting

engagement practices in the proposed strategy? Was

it necessary in the projects you participated in? In

your experience, does this practice facilitate an

improvement in the quality of the process of

including UX practices or adopt other practices? If

he would adopt other practices, what would they be?

THANK YOU VERY MUCH FOR

PARTICIPATION.

ICEIS 2018 - 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

568