Cloud Strategies for Software Providers: Strategic Choices for SMEs in

the Context of the Cloud Platform Landscape

Damian Kutzias

1

and Holger Kett

2

1

Institute of Human Factors and Technology Management IAT, University of Stuttgart, Nobelstraße 12, Stuttgart, Germany

2

Fraunhofer Institute for Industrial Engineering IAO, Fraunhofer Society, Nobelstraße 12, Stuttgart, Germany

Keywords:

Cloud Computing, Cloud Platforms, Platform Economics, Cooperation, Integration, Small and Medium-Sized

Enterprises, SME, Business Sector Focus, Strategic Decisions, Strategy, Cloud Ecosystems.

Abstract:

Within this paper, the fundamental question of the hosting challenge for software providers starting with the

cloud business, becoming Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) providers, is discussed. Selecting a hosting provider

and consuming Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS) is a common and viable solution. Some cooperation-based

strategic choices are presented as alternative solutions and compared to the more common approaches. These

can hold great potential, especially for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SME) when applied meaning-

fully. For that, the relevant terms Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS) and Cloud Ecosystem are discussed, differ-

entiated and defined with regards to existing definitions and their ambiguities. Following, the outset and

challenges are described focussing on the case of SME providers. Last but not least, different strategic choices

are presented with their advantages, disadvantages and challenges. These choices are presented in an overview

matrix roughly weighted with relative responsibilities as well as ecological and strategic aspects.

1 INTRODUCTION

Cloud Computing has the potential to transform cap-

ital expenditure to operational expenditure and fa-

cilitates flexibility in developing. It may allow a

stronger focus on the core competences and can cre-

ate value relevant for competitiveness and corporate

growth (Mitra et al., 2018). Whereas the advantages

of cloud computing involve huge potentials, there is

also a shift in the challenges and IT related tasks for

the enterprises accompanied. Challenges arise espe-

cially in the business process management and on the

technical side in the areas of IT security, data mi-

gration, interface definition, customizing, and mobile

application development (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2018).

It is also considered as a value adding (trend) tech-

nology transforming value chains to complex value

ecosystems (Rafique et al., 2012).

With an enterprise adoption of over 90 percent

(RightScale, 2018) even for public clouds, Cloud

Computing has exceeded the trend technology sta-

tus and has become a fundamental part of the tech-

nology landscape for many enterprises, the every-

day life and work processes. Even in more cautious

countries such as Germany, the public cloud adoption

has drastically increased from roughly six percent in

2011 (Pierre Audoin Consultants, 2012) to 29 percent

in 2016 (KPMG AG Wirtschaftspr¨ufungsgesellschaft

and Bitkom Research GmbH, 2017).

There is plenty of literature about the challenges,

advantages and potentials of the use of cloud com-

puting for consumers. In addition to the beforemen-

tioned references, Marston et al. list entry cost for

compute-intensive business analytics, almost imme-

diate access to hardware resources, lowering of IT

barriers to innovation, service scaling for enterprises

and enabling of new applications as the five main ad-

vantages of cloud computing (Marston et al., 2011).

On the other hand, Avram lists security and privacy,

connectivity and open access, reliability, interoper-

ability, economic value, changes in the IT organi-

sation and political issues due to global boundaries

as barriers (Avram, 2014). In contrast, publications

making the strategic view of cloud software providers

the subject of discussion, are rare to find. The trend

of switching offerings from on-premises solutions to

web-based cloud solutions with a focus on pricing

models and advertisements in that context as well as

the impact on users and the pricing models is evalu-

ated in (Jhang-Li and Chiang, 2015).

In (Carvalho et al., 2017), capacity planning for

Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS) provider respecting

Kutzias, D. and Kett, H.

Cloud Strategies for Software Providers: Strategic Choices for SMEs in the Context of the Cloud Platform Landscape.

DOI: 10.5220/0006932202070214

In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST 2018), pages 207-214

ISBN: 978-989-758-324-7

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

207

service level agreements is evaluated. In addition, a

planning method is proposed for optimising the CPU

utilisation.

Regarding the strategic view, in (Wang and He,

2014) SMEs in Taiwan were investigated with the fo-

cus on late entrants to the cloud service provider mar-

ket. Main challenges with a focus on business mod-

els are discussed and strategy alternatives are sum-

marised in a strategy matrix to bolster the competi-

tiveness of SME cloud service providers.

Strategic alliances for the case of SMEs are

discussed in (O’Dwyer and Gilmore, 2018). The

significance, especially for expanding capabilities

and value optimisation is emphasized in addition to

the strong customer focus of SMEs. The research

is focused on the success of alliances and longevity,

especially by providing help for partner selection.

When talking about SMEs in this paper, the defi-

nition of the European Commission meant, i.e. a staff

less than 250, the turnover less or equal to 50 million

euros and the balance sheet less or equal to 43 million

euros (European Commission, 2005).

2 THE CLOUD PLATFORM

LANDSCAPE

This section provides an overview over the relevant

platform types and terms, highlights ambiguities and

gives a suggestion for the terminology.

The terms Platform as well as Platform-as-a-

Service (PaaS) are used in many different contexts

with several definitions. The ambiguities even per-

sist when only talking about cloud Platforms. For

some authors, PaaS refers to cloud based integrated

development environments (IDE) such as in (Lawton,

2008). PaaS is also defined and used as managed IaaS

which is the case in (Jadeja and Modi, 2012). For

the PaaS definition, some others include middleware

services such as billing, authentication and authori-

sation (Boniface et al., 2010). This also matches the

definition of the National Institute of Standards and

Technology (NIST) (Mell and Grance, 2011). Even

in the cloud context, PaaS is not always referred to as

a cloud service model including cloud technologies,

but also supporting technologies such as in (Li et al.,

2017). In this case, PaaS is used as a synonym for a

DevOps environment.

Detached from the as-a-Service, the term (cloud)

Platform is also often used for any kind of PaaS. It is

also used for cloud infrastructure and therefore also

in combination with or synonym for IaaS such as in

(Han, 2013). Last but not least, Platform refers to

all kinds of cloud marketplaces. These marketplaces

may or may not include any kind of PaaS such as in

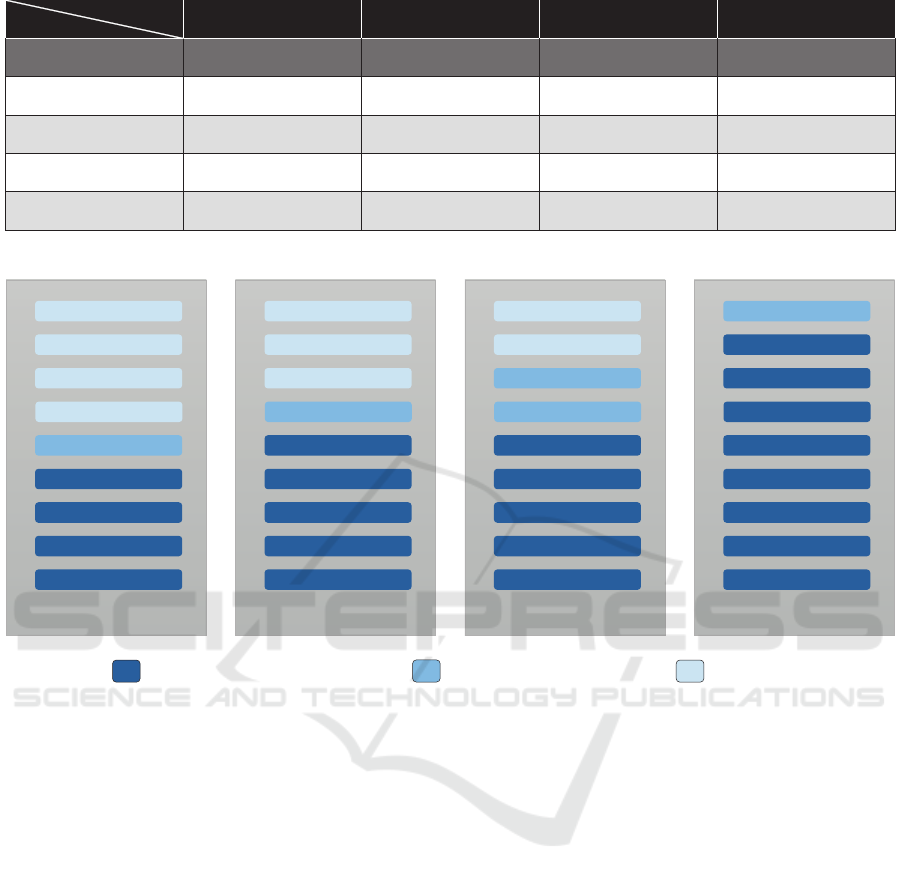

(ComputeNext Team, 2016). An overview over the

identified differences and ambiguities of the explicit

definitions can be seen in Figure 1. The characteris-

tics are described in the following:

IaaS directly sold means, that infrastructure such

as storage, network or computation power is one

of the main components sold.

IaaS implicitly sold means, that infrastructure as

mentioned above, is a part which is used by the

service sold, but not the main component.

Developer Tools and environment covers fully

integrated IDEs as well as Application Program-

ming Interfaces (APIs) and other tools bolstering

the development and deployment process.

Middleware Services in this context are as de-

scribed above, more complex software tools and

services such as invoice and billing systems. Such

middleware services reduce the required efforts to

provide a sound SaaS solution enabling a focus on

the core features of the solution.

When writing about PaaS in this paper, a cloud

based developing and deployment environment with

infrastructure included is meant. To differentiate, the

term Basic PaaS is used for a variant which does not

include more complex middleware such as services

for billing, authentication or single sign on. In

addition, Extended PaaS is used when more complex

middleware as mentioned before is included. An

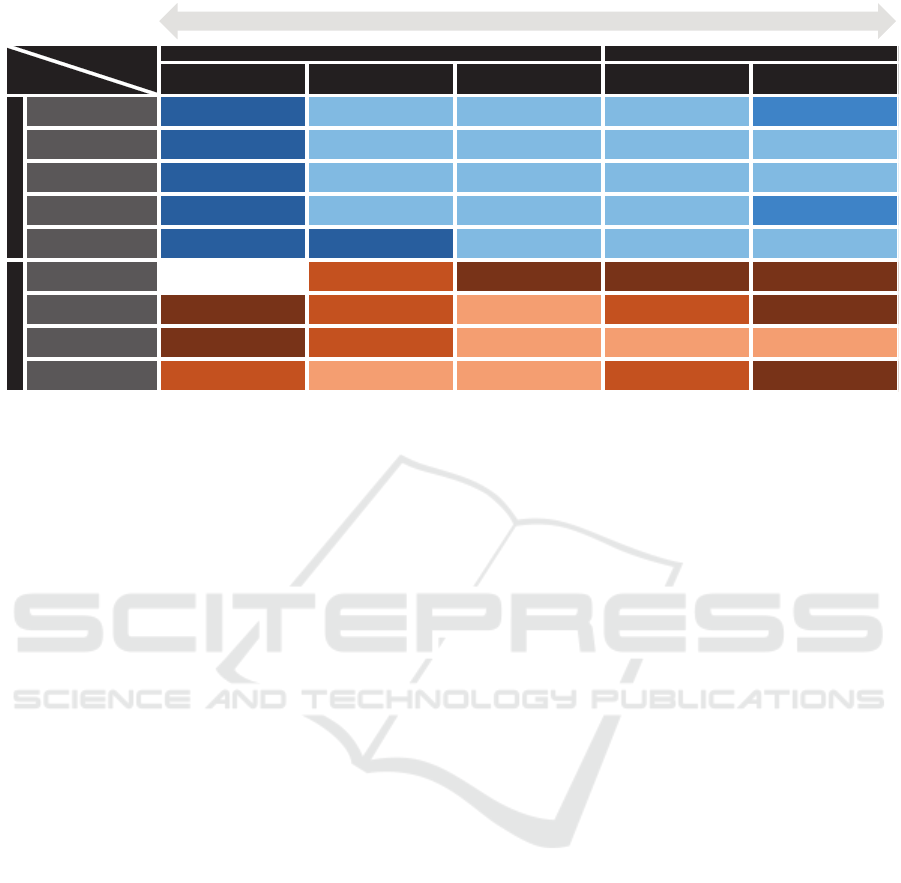

overview over the responsibilities for the operation

and providing of the most central components of

cloud services can be seen in Figure 2.

When taking a more holistic view, the term Cloud

Ecosystem becomes relevant. A cloud ecosystem can

be defined as a complex system of interdependent

components that all work together to enable cloud

services (Rouse et al., 2018). Sometimes the term

Cloud Ecosystem is used for spanning everything re-

lated to cloud computing as one big ecosystem such

as in (Marinescu, 2018). In this paper, the first def-

inition is used with a Platform, provider or a solu-

tion as the center of the Cloud Ecosystem. In addi-

tion, every related physical component as well as ev-

ery stakeholder and their connections are parts of the

ecosystem. Cloud providers can purposeful cultivate

their ecosystem to add value for the stakeholders and

especially their customers. For example, this can be

done by maintaining communities, events and infor-

mation exchange such as best practises between the

stakeholders.

WEBIST 2018 - 14th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

208

Usage

Characteristics

PaaS as Cloud IDE

PaaS as managed

IaaS

PaaS with Middleware PaaS as DevOps

Source (Lawton, 2008) (Jadeja and Modi,

2012)

(Boniface et al., 2010) and

(Mell and Grance, 2011)

(Li et al., 2017)

IaaS directly sold

✓

✓

IaaS implicitly sold

✓

✓ ✓

Developer Tools and

Environment

✓ ✓ ✓ ✓

Middleware Services

✓

Figure 1: Overview over the differentiation of diverse usages of the term PaaS.

Data Center

IaaS

Network

Server

Virtual Machines

Middleware

Developer Tools

Applications

Provider Managed

Shared or Varying

Storage

Self Managed

Data

Data Center

Basic PaaS

Network

Server

Virtual Machines

Middleware

Developer Tools

Applications

Storage

Data

Data Center

Extended PaaS

Network

Server

Virtual Machines

Middleware

Developer Tools

Applications

Storage

Data

Data Center

SaaS

Network

Server

Virtual Machines

Middleware

Developer Tools

Applications

Storage

Data

Figure 2: Suggestions for the PaaS differentiation and usage in the context of other cloud service models in a graphical

representation adapted from Gartner (Cancila et al., 2016).

3 OUTSET AND CLOUD

RELATED CHALLENGES

3.1 Overview and Challenges

The cloud adoption has drastically increased over the

last years. Most recent surveys show that a majority

of enterprises is using cloud computing. A survey

of RightScale in January 2018 is pointing out, that

92 percent of the enterprises are using public clouds.

This increases to 96 percent when private clouds are

included (RightScale, 2018). In contrast to the high

adoption and acceptance, there is still much potential

for cloud solutions left. According to Capgemini,

the share of used IT-systems was only 10.2 percent

for public clouds and 36.6 percent for private clouds

(Scheid et al., 2017), making the offering of cloud

solutions a reasonable and maybe even required

decision for software providers.

Following the cloud definition of the National Insti-

tute of Standards and Technology (NIST), two of the

essential characteristics of cloud computing are on-

demand self-service and rapid elasticity (Mell and

Grance, 2011). The first means that a consumer can

get the services and their resources without human in-

teraction. The latter stands for the availability of prac-

tically unlimited resources for the consumers.

When established providers of conventional soft-

ware start offering Software-as-a-Service (SaaS),

many important decisions have to be made in order to

handle the above mentioned two characteristics. Es-

pecially for SME the choices are often crucial due to

limited resources and expertise, in particular when it

comes to the data centre maintenance and tasks. Some

of the main challenges regarding this crucial area are:

Rapid Elasticity: to guarantee the practically

unlimited amount of resources, huge reserves of

hardware are necessary

Reliability: a standard requirement for prevent-

Cloud Strategies for Software Providers: Strategic Choices for SMEs in the Context of the Cloud Platform Landscape

209

ing data loss and to ensure high availability of

service for cloud computing is to maintain ge-

ographically separated redundancies resulting in

even higher investment costs.

Security: Compared to dedicated servers, data

centres need professional business operation be-

cause of the multi-tenancy requirements.

The most common solution for the data centre prob-

lem is consuming IaaS, Basic PaaS or Extended PaaS

from a data centre provider. In the role of a con-

sumer of cloud services, SaaS-provider have to care-

fully choose the data centre provider. Some of the

main challenges and criteria are listed and described

in the following:

Vendor-Lock-in: Depending on the needs of

the SaaS-provider as well as the modality of

the data centre resource provision, data formats

and Service Level Agreements (SLA), there is a

risk of strong dependencies from the data centre

provider.

Hosting Location: The geographical locations

of the data centres of the provider. The rele-

vance comes from performance when providing

real time services as well as huge amounts of data,

the applicable law and customer needs and prefer-

ences.

Customer Contact: Some of the more complex

solutions, especially the Extended PaaS Solutions

sometimes offer or automatically include a sales

channel. This can be a great advantage for finding

new customers, but usually also includes a share

of the revenue as additional fees and should there-

fore be considered carefully.

Depending on the end-consumer needs, some of

these criteria might be of less importance. As an ex-

ample, the hosting location might be subordinated to

the other criteria depending on the country and the

field of application. In some countries, such as Ger-

many, it is often required, that the hosting location

is in the same country or at least in the same conti-

nent due to legal reasons or customer demands. If the

application itself has no crucial contents such as per-

sonal or medical data to handle, the mentality of the

end-consumers often demands proximity of the data

centres. To be convinced of a cloud provider or so-

lution, the trustworthiness, especially when subcon-

tractors are involved has to be backed for some cus-

tomers, e.g. by certificates. Depending on the legal

area, certificates might even be mandatory or at least

necessary to prevent legal liability for the services of

the data centre provider.

3.2 Business Sector Differences

A lot of surveys and papers investigate the cloud

adoption and the impact of cloud usage to the per-

formance of enterprises. Many of these surveys pro-

vide an overview of enterprises without a specific fo-

cus of the business section or application field such as

(RightScale, 2018) or (Scheid et al., 2017). Some oth-

ers take the business section into account, usually dis-

covering notable differences such as (Pierre Audoin

Consultants, 2012). Regarding to the cloud adoption,

enterprises of the information and communications

technology (ICT) business section are generally more

advanced than enterprises from the retail or manufac-

turing section, whereby the retail section is outpac-

ing the manufacturing section. Regarding the core

competences, manufacturing enterprises are more ad-

vanced in using and planning with cloud solutions

such as big data analytics and industry 4.0 (Falkner

et al., 2018).

Accodring to (ClearTechnologies, 2018), choos-

ing the right cloud solution is a tough decision and

there are endless numbers of solutions. ClearTech-

nology also states that industry specialisation should

be considered while searching the right solutions.

With the varying requirements in mind, cloud Plat-

form provider can add value by maintaining business

sector focus on the Platform level, e.g. by providing

search/categorisation support and clear separations as

well as maintaining communities.

4 STRATEGIC CHOICES AND

POTENTIALS

Instead of just using IaaS or basic PaaS from a data

centre provider, there are different alternatives Soft-

ware providers without own data centres when be-

coming SaaS providers. Two such alternatives are

presented in the following, namely integration to ex-

tended PaaS or ecosystems and strategic cooperation.

4.1 Platform Integration

When choosing Extended PaaS or even an ecosys-

tem including Extended PaaS, many of the technical

and organisational challenges can be solved by the

Platform provider. This usually comes at the cost of

higher integration expenditures and therefore an in-

creased vendor-lock-in. The following characteristics

of Extended PaaS may be considered for the selection

of a provider. The focus is on strategic components

and fundamental characteristics such as service level

WEBIST 2018 - 14th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

210

agreements (SLAs), costs, certifications and vendor

lock-in:

Strong Ecosystem: A strong and cultivated

ecosystem with the Platform as the center and

a strong community and knowledge transfer sys-

tem build around it can be of great value for cus-

tomers, e.g. by providing best practises and use

cases to them. In addition, it can be an envi-

ronment for finding strategic partners, gaining an

overviewover the market or knowledge exchange.

Middleware Extent: Middleware services ex-

ceeding the necessary extent can save much ef-

fort when developing and providing cloud ser-

vices. Common examples for such middleware in

the context of extended PaaS range from common

services such as billing, support assistance (e.g.

ticket systems), single sign on, user management

and monitoring to more specific ones such as de-

vice management or integration by standards and

interfaces.

Existence of a Marketplace Component: Some

PaaS ecosystems also contain a marketplace as a

sales channel for their customers. Usually, a share

of the revenue has to be paid to the Platform in

exchange for the marketing gained.

Business Sector Focus: Especially for market-

places, but not restricted to them, business sector

focus can be of relevance. When containing many

different solutions a selection and search taking

the business sectors into account can be of value.

In addition, the provided middleware can have a

business sector focus by providing specific ser-

vices such as device and sensor management for

the Internet of Things (IoT) or manufacturing in

the context of Industry 4.0.

Focus on Customer Needs: Depending on the

business sector or generally the customer group,

the Platform may be designed for the needs of

the customers or even contain interactive parts to

achieve this such as crowd sourcing.

While having huge potential of saving efforts,

some of the characteristics or services can also turn

a drawback, e.g. when they rise the overall costs of

the extended PaaS solution for enterprises which do

not need them because of already existing own solu-

tions.

4.2 Strategic Cooperation

As an alternative to consume IaaS or Basic/Extended

PaaS for SaaS market entrants in the customer role,

another possibility for them is to find partners for

strategic cooperation. Two different ways of such

strategic cooperation, namely joint ventures and SaaS

cooperation are described in the following.

4.2.1 Joint Ventures: New Product

When the establishment of own data centres is not

feasible for one enterprise, it may be in a joint ven-

ture. On the one hand, usually many organisational,

legal and technical challenges have to be faced. On

the other hand, the advantages include independency,

needs-based design and in the long term potentially

lesser costs or a resulting Extended PaaS which can

be offered as a standalone service yielding revenue

itself. An example for a strategic cooperation with

a business sector focus as mentioned in the previ-

ous section is ADAMOS (ADAptive Manufacturing

Open Solutions). ADAMOS is a strategic alliance and

joint venture of several enterprises creating solutions

for Industry 4.0 and the Industrial Internet of Things

(IIoT) with the two main focuses of 1. IIoT-Plattform

and 2. App Factory (ADAMOS GmbH, 2017).

4.2.2 SaaS Cooperation: Bundle Offers

Another alternativeis a strategic cooperation of two or

more enterprises, where at least one can provide the

infrastructure or Platform environment. In this case,

there are also organisational, legal and technical chal-

lenges to be faced, but without the foundation of a

new enterprise. This might increase the legal but also

reduce the technical expenditure. The different enter-

prises have no customer relationship in between them

but are strategic partners offering one or more solu-

tion bundles and have their shares and responsibilities

for the offered solutions.

4.3 Overview and Distinction

An overview over the choices and alternatives with a

rough classification of technical responsibilities and

ecological ratings can be seen in Figure 3. The

overview has the perspective of software providers

starting with the SaaS business, i.e. providers without

own cloud-ready data centres. Responsibilities for the

main technical challenges are listed in the upper part

of the table. Ecological and strategic aspects are listed

in the lower half focusing on resource invest and risk.

The alternatives are described in the following:

Do it Yourself: This alternative means building

and maintaining cloud-ready data centres and car-

ing for all technical challenges. Therefore there

is no vendor lock-in, but the investment is high as

well as the implementation overhead. There are

Cloud Strategies for Software Providers: Strategic Choices for SMEs in the Context of the Cloud Platform Landscape

211

Do it Yourself

Consume IaaS or Basic

PaaS

Consuming Extended PaaS

Cooperation by Contracts:

Bundle Offerings

Cooperation: Joint Venture

(new Product)

Rapid Elasticity Self Provider Provider Partner Shared

Reliability Self

Provider Provider Partner Partner

Security Self Provider Provider Partner Partner

Hosting Location Self Provider Provider Partner Shared

Middleware

Implementation

Self Self Provider Partner Partner

Vendor Lock-in Risk - Medium High High High

Investment Amount High Medium

Small Medium High

Implementation

Overhead

High Medium Small Small Small

Organisational

Overhead

Medium Small Small Medium High

Classic Approaches

Strategic Cooperations

Ecologic / Strategic

Technical

Approach

Challenge

High Costs or Complexity of own Solution High Complexity of the Network / Cooperation

Figure 3: Strategic choices from the perspective of software providers in the role of entrants to the SaaS market without own

data centres: the complexity, technical responsibilities and ecological/strategic ratings in a rough overview. Responsibilities

are illustrated in blue with darker colours meaning more responsibility for the software provider. Ecological and strategic

values are illustrated in brown whereat darker colour means higher expenditure or risk for the software provider.

also many organisational challenges to solve, but

limited to one enterprise and its processes.

Consume IaaS or Basic PaaS: The challenges

related to the infrastructure are the responsibil-

ity of the provider, but the middleware has to be

implemented. There is a medium vendor lock-

in risk due to customer contracts, the stored data

and the system or API from the vendor. There is

medium investment necessary due to the missing

middleware which has to be bought or integrated.

Since most crucial parts are the responsibility of

the IaaS or Basic PaaS provider, there is only a

relative small amount of organisational overhead.

Consuming Extended PaaS: In addition to the

infrastructure, also (most of) the middleware is

bought as part of the Extended PaaS, leaving

the technical challenges to the Extended PaaS

provider. With this, many processes of the enter-

prises rely on the Extended PaaS provider, result-

ing in a hight vendor lock-in. The investment is

small, since the costs are mainly operational and

there is no huge implementation or organisation

overhead.

Cooperation by Contracts: Bundle Offerings:

SaaS is offered by more than one enterprise in a

partnership. Instead of a IaaS or PaaS provider, a

strategic partner takes care of the technical chal-

lenges. Since there is at least one partner offering

the SaaS bundle, the vendor lock-in (partner) usu-

ally is high. The medium investment comes from

the adaptations with the partners and creating the

necessary contracts. Whereas no hosting related

implementation has to be done, the medium or-

ganisational overhead also comes from the part-

nership and bundle adaptations, especially the set-

up of joint business processes.

Cooperation: Joint Venture (new Product): A

new enterprise is founded with joint resources and

know-how. The challenges related to the infras-

tructure are initially solved by the resources of

the founding partners. Rapid Elasticity and Host-

ing location are directly related to the resources

of the founding partner, especially the investment

amount. Whereas the infrastructure related im-

plementation overhead is small for the software

provider, vendor lock-in (partner), the investment

amount and the organisational overhead are high.

At first glance, except for the implementation

overhead, cooperation performs poorly in comparison

with huge expenditure and high risk. But cooperation

also comes with additional degrees of independence,

since it is not a consumer relationship, but a partner-

ship instead. Especially for the case of a joint venture,

the solution can be needs-based to the own solution

and there can be revenue from selling the Extended

PaaS as a standalone solution bolstering the attractive-

ness from the ecological perspective.

5 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

The areas of Cloud Computing and Software-as-

a-Service are still in motion. Some ambiguities

WEBIST 2018 - 14th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

212

exist for the terminology, especially for the terms

Platform and Platform-as-a-Service, where this

paper has given an overview over the usage and

suggested a differentiation by listing and describing

common Platform characteristics with a mapping to

the several existing definitions. In addition to that,

strategic obstacles arise when starting as a cloud

service provider. An overview over the outset and

challenges was given, focusing on the core challenge

of the hosting problem which arises when providing

real cloud services regarding to rapid elasticity and

on-demand-self-service. Some additional aspects

such as possible business sector focus and the corre-

sponding relevance were also discussed. Regarding

possible solutions, joint ventures and contract-based

cooperation are presented in the context of more

familiar approaches such as consuming infrastructure

from a data centre provider examining the advantages

and disadvantages. For these alternatives, a rough

overview over the responsibilities and resources is

given.

Whereat this paper is focused on giving an

overview and understanding the basics of strategic

decisions for entrants to the SaaS market, future re-

search could be more detailed investigations of the

strategic sub-challenges and grant specific recom-

mendations for action or decision-making aids. Es-

pecially for cooperation contracts many questions re-

main open such as legal responsibilities, shares and

best practises. Also statistics to give more precise in-

formation about the necessary resources required for

cooperation would add value to the topic of strategic

alliances.

REFERENCES

ADAMOS GmbH (2017). ADAptive Manufacturing Open

Solutions. https://de.adamos.com/.

Avram, M. G. (2014). Advantages and Challenges of

Adopting Cloud Computing from an Enterprise Per-

spective. Procedia Technology, 12:529–534.

Boniface, M., Nasser, B., Papay, J., Phillips, S. C., Servin,

A., Yang, X., Zlatev, Z., Gogouvitis, S. V., Katsaros,

G., Konstanteli, K., Kousiouris, G., Menychtas, A.,

and Kyriazis, D. (2010). Platform-as-a-Service Ar-

chitecture for Real-Time Quality of Service Manage-

ment in Clouds. In 2010 Fifth International Confer-

ence on Internet and Web Applications and Services,

pages 155–160. IEEE.

Cancila, M., Toombs, D., Waite, A., and Khnaser, E. (2016).

2017 Planning Guide for Cloud Computing.

Carvalho, M., Menasc´e, D. A., and Brasileiro, F. (2017).

Capacity planning for IaaS cloud providers offering

multiple service classes. Future Generation Computer

Systems, 77:97–111.

ClearTechnologies (2018). Finding the Right Cloud Solu-

tion.

ComputeNext Team (2016). Cloud Marketplace Platform:

7 Key Factors to Choose the Right Platform for your

Business.

European Commission (2005). The new SME definition:

User guide and model declaration. Enterprise and in-

dustry publications. Off. for Off. Publ. of the Europ.

Communities, Luxembourg.

Falkner, J., Kutzias, D., H¨arle, J., and Kett, H. (2018).

Cloud Mall Baden-W¨urttemberg: Eine Umfrage zur

Nutzung von Cloud-L¨osungen bei kleinen und mit-

telst¨andischen Unternehmen in Baden-W¨urttemberg.

Fraunhofer Verlag, Stuttgart.

Han, Y. (2013). IaaS cloud computing services for libraries:

cloud storage and virtual machines. OCLC Systems

& Services: International digital library perspectives,

29(2):87–100.

Jadeja, Y. and Modi, K. (2012). Cloud Computing: Con-

cepts, Architecture and Challenges. IEEE, Piscat-

away, NJ.

Jhang-Li, J.-H. and Chiang, R. (2015). Resource allocation

and revenue optimization for cloud service providers.

Decision Support Systems, 77:55–66.

KPMG AG Wirtschaftspr¨ufungsgesellschaft and Bitkom

Research GmbH (2017). Cloud-Monitor 2017: Cyber

Security im Fokus: Die Mehrheit vertraut der Cloud.

Lawton, G. (2008). Developing Software Online With

Platform-as-a-Service Technology. Computer, (6):13–

15.

Li, Z., Zhang, Y., and Liu, Y. (2017). Towards a full-

stack devops environment (platform-as-a-service) for

cloud-hosted applications. Tsinghua Science and

Technology, 22(01):1–9.

Marinescu, D. (2018). Cloud Service Providers and the

Cloud Ecosystem. In Cloud Computing, pages 13–49.

Elsevier.

Marston, S., Li, Z., Bandyopadhyay, S., Zhang, J., and

Ghalsasi, A. (2011). Cloud computing — The

business perspective. Decision Support Systems,

51(1):176–189.

Mell, P. and Grance, T. (2011). The NIST definition of cloud

computing. National Institute of Standards and Tech-

nology, Gaithersburg, MD.

Mitra, A., O’Regan, N., and Sarpong, D. (2018). Cloud re-

source adaptation: A resource based perspective on

value creation for corporate growth. Technological

Forecasting and Social Change, 130:28–38.

Nieuwenhuis, L., Ehrenhard, M., and Prause, L. (2018).

The shift to Cloud Computing: The impact of dis-

ruptive technology on the enterprise software busi-

ness ecosystem. Technological Forecasting and Social

Change, 129:308–313.

O’Dwyer, M. and Gilmore, A. (2018). Value and alliance

capability and the formation of strategic alliances in

SMEs: The impact of customer orientation and re-

source optimisation. Journal of Business Research,

87:58–68.

Cloud Strategies for Software Providers: Strategic Choices for SMEs in the Context of the Cloud Platform Landscape

213

Pierre Audoin Consultants (2012). Cloud-Monitor 2012.

Rafique, K., Yuan, C., Wahid Tareen, A., Saeed, M., and

Hafeez, A. (2012). Emerging lCT Ecosystem: From

Value Chain to Value Ecosystem. 2012 8th Interna-

tional Conference on Computing Technology and In-

formation Management (NCM and ICNIT).

RightScale (2018). RightScale 2018 - State of the Cloud

Report: DATA TO NAVIGATE YOUR MULTI-

CLOUD STRATEGY. RightScale.

Rouse, M., Sparapani, J., and Herbert, L. (2018). The his-

tory of cloud computing and what’s coming next: A

CIO guide: Definition cloud ecosystem.

Scheid, K., Pr¨adel, J.-M., Emenako, D., Ogulin, G., and

Luley, T. (2017). Studie IT-Trends 2017:

¨

Uberfordert

Digitalisierung etablierte Unternehmensstrukturen.

Capgemini.

Wang, F.-K. and He, W. (2014). Service strategies of

small cloud service providers: A case study of a

small cloud service provider and its clients in Tai-

wan. International Journal of Information Manage-

ment, 34(3):406–415.

WEBIST 2018 - 14th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

214