Women and Technologies: Towards a Gendered Profile

of Digital Do-It-Yourself Workers?

Carolina Guerini, Eliana Minelli and Aurelio Ravarini

Dipartimento in Gestione Integrata d’Impresa, Università Carlo Cattaneo – Liuc, Castellanza, Italy

Keywords: Digital Do-It-Yourself, Women, Didiyer’s Profile, Expert Amateur, Digital Literacy.

Abstract: Though yet partly unexplored, Digital Do-It-Yourself (DiDIY) is both an objective phenomenon that can be

investigated from the point of view of its output and a subjective phenomenon that shapes individual behaviors

and can be analyzed from the perspective of competences, motivations and social relationships. DiDIY is a

complex socio-technical phenomenon that heavily impacts on organizations. Following recent research paths

aimed at defining the subjective side of DiDIY, this research focuses on the gendered DiDIYer’s profile.

Female DiDIYers’ personal characteristics seem to confirm previous studies dealing with the general

DiDIYer’s profile (Guerini and Minelli, 2018). They are digitally literate and aware of their skills, curious

and eager to innovate. Proud and conscious of their potential contribution to the improvement of their lives

and their workplace, open to professional and personal challenges, they qualify themselves as expert amateur,

not just as pure technology adopters. Female DiDIYers are involved in organic and participative cultures and

their roles are characterised by knowledge sharing and creation, also through communities of practice. Female

DiDIY is concentrated in complex roles, which link the organization to the external environment, being

intrinsically autonomous in their expression and far from clerical activities.

1 INTRODUCTION

Digital Do-It-Yourself (DiDIY) is an approach to

carry out activities aimed at autonomously creating,

modifying or maintaining objects and services. A

DiDIYer is any individual adopting this approach by

exploiting digital technology (DT) that reduce (or

remove) the need of an expert to carry out such tasks

(Mari, 2014). For example, a DiDIYer can be a

worker in a manufacturing firm, carrying out

prototyping activities without asking support of

engineering firms, using 3D printers.

More broadly, the term DiDIY describes the

phenomenon of the worldwide diffusion of such

approach in the socio-economic environment. It

stems from the convergence of multiple factors: the

wide availability of digital tools, a general diffusion

of a deeper knowledge and mastery of ICT among

large portions of the population and a large

accessibility of databases through open online

communities (Digital DIY, 2017).

One can see DiDIY as an objective phenomenon,

that can be investigated from the point of view of its

output (e.g. tools, products or collaboration

structures). At the same time it is a mindset (related

to a culture of production and consumption), hence a

subjective phenomenon that shapes individual

behaviors and can be analyzed from the perspective

of competences, motivations, social relationships.

These two views of DiDIY are intertwined and

mutually influencing. Thus, DiDIY as a complex

“socio-technical” phenomenon has a heavy impact on

organizations. Though yet partly unexplored, DiDIY

is getting an increasing interest in the scientific

literature. Some principles receive a large support and

are exposed in relevant institutional websites

(http://www.didiy.eu).

We build on such principles to investigate the

DiDIY phenomenon where the DiDIYer is a woman.

Gender implications related with IT adoption and use

are not a new research subject (Wajcman, 2007;

Roomi, 2009), but we are interested in investigating

whether the diffusion of a DiDIY mindset can find a

particularly effective domain amongst women.

In this paper we follow the research stream about

the subjective side of DiDIY, focusing on the

gendered DiDIYer’s profile and investigating the

characteristics that differentiate the female DiDIYer’s

profile from the ungendered one. In the next sections

we review the literature related to DiDIY and to the

186

Guerini, C., Minelli, E. and Ravarini, A.

Women and Technologies: Towards a Gendered Profile of Digital Do-It-Yourself Workers?.

DOI: 10.5220/0006933001860193

In Proceedings of the 10th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2018) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 186-193

ISBN: 978-989-758-330-8

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

use of digital technology according to a gendered

perspective. We then discuss the general implications

of the DiDIY phenomenon on the organizational

change. Based on this theoretical background, we

introduce the empirical study and finally discuss the

evidences collected from about 600 answers to a

questionnaire, leading to a preliminary view of

women’s approach to digital technologies and

DiDIY.

2 THE DiDIY PHENOMENON

The DiDIY phenomenon is the recent evolution of the

broadly studied phenomenon of DIY, or Do-It-

Yourself (Edwards, 2006). Several scholars in the

past ten years have noted that the progress in digital

technology has supported the development of

autonomy in performing tasks of any type, as well as

the rise of an “entrepreneurial” attitude in individuals

with very different interests and background

(Hoftijzer, 2009; Kuznetsov and Paulos, 2010).

More recently, the term “Maker” (Anderson,

2012) gained wide popularity as a label to

characterize individuals, who, in addition to such

mindset, exploit the interaction within communities

of peers to accelerate the development of skills

through a shared approach to problem-solving,

supported by the use of social-networking platforms,

such as blogs, wikis, and any other social media

available (Buxmann and Hinz, 2013). However,

“Makers” usually refers to communities of subjects

involved in manufacturing activities. On the contrary,

there is evidence that DiDIY, as a mindset and as an

activity, can indeed take place within existing work-

places belonging to any industry, e.g. in hospitals, in

retail companies (Ravarini and Strada, 2018).

The research carried out in several organizational

contexts led to isolate a set of properties characteriz-

ing the profile of a DiDIY worker: job attitude,

autonomy, failure positive, multidisciplinary,

playfulness, anti-consumerism behaviour, computa-

tional thinking (Cremona and Ravarini, 2016).

A scholarly work by Guerini and Minelli (Guerini

and Minelli, 2018) researched these fundamental

traits of a DiDIYer in the context of network

marketing. This paper is focused on NMDSOs

(Network Marketing Direct Selling Organizations)

where the DiDIYers are networkers. Guerini and

Minelli’s exploratory study suggests a series of items

to be considered in defining the subjective side of

DiDIY, i.e. the DiDIYers’ profile, that we outline in

the following paragraphs.

The drivers that motivate networkers to behave as

DiDIYers can be described as an internal force

(curiosity, intention to take on a challenge, a desire to

experiment creatively) or as a momentary thrill, thus

qualifying this DiDIYer’s mindset as passionate. The

community vision largely overcomes the interest in

individual benefits: the autonomy of direct

salespeople and the existence of downlines (or

communities of practice) encourage individuals to

exploit unique competences and be the creator of the

environment. Performance effects awareness and

performance measurement are, on the contrary,

neglected by networkers, though collaboration,

cohesion and mutual reinforcement are important in

network marketing culture, and DT is considered one

of the means that guarantees all that through

connectivity. On the other hand, it is the community

appraisal of the individual role embedded in network

marketing culture that feeds motivation and favours

the adoption of a DiDIY-like mindset. Information

technology is increasingly used by personnel engaged

in network marketing activities also as a means to

encourage collective action in support of the

advancement of an ideology or idea (Oh et al., 2013).

In this sense community-building, and action-

oriented messages (Lovejoy and Saxton, 2012) seems

to pertain to an ‘ideology of sharing’ in that network

marketers consider this activity much more as a

typical way of life rather than as an alternative

distribution model for goods and services (Guerini

and Minelli, 2016).

2.1 Gendered Technology

The joint consideration of gender and technology is at

the heart of this research project. The central premise

of feminist techno science is that people and artefacts

co-evolve: the materiality of technology affords or

inhibits particular gender/power relations, such as

gender division of labour. It foregrounds the need to

investigate the ways in which women’s identities,

needs and priorities are being reconfigured together

with digital technologies also in relation to different

groups and diverse real-world locations (Wajcman,

2007; Anwar et al., 2017). Despite women’s massive

consumption of new media, Internet and social

networks do not transform every user into an active

producer, and they do not include every woman into

the network society. The potential for empowerment

offered by ICTs can be realized through technical

skills because gender imbalance in technical expertise

turns out to be an important obstacle to full inclusion

into the digital society and to enjoy the opportunities

it opens up (Wajcman, 2007).

Women and Technologies: Towards a Gendered Profile of Digital Do-It-Yourself Workers?

187

In the organisational context, the relationship

between gender and technology is still complex

(Eriksson-Zetterquist, 2007) because of women’s

vertical and horizontal segregation. Technology has

been always associated to men since its diffusion after

World War II. Moreover, women who try to escape

glass ceiling phenomena through self-employment

and entrepreneurship in the ICT sector face

hindrances in the access to technological and social

capital (Halford and Savage, 2010).

Recent studies focus on how technologies are

associated with the crystallization of social relations

of different kinds, which endure and foster the

production and accumulation of practices and

activities of various kinds (Halford and Savage, 2010)

giving rise to “the particular knowledge/power

relations that establish the hegemonic norms of

gender … and technology in particular contexts”

(Butler, 2004, p. 216).

These aspects couple with the issue of access to

technological and social capital, which is critical to

the development of technological businesses. In

particular, the literature on women entrepreneurs

stresses their lack of social capital as an impediment

to expanding their businesses. Some scholars (Roomi,

2009) observe that the production of social capital is

influenced by a strict gender labour-division.

In brief, even if the debate on the relation between

technology and gender is lively, and the concerns

about the inclusion of women in the technological

context are steady, research in this domain doesn’t

focus attention on the role of those women that create,

modify or maintain objects and services based on

digital technologies, being a worker or, eventually, a

customer and a co-creator.

2.2 The Research Questions

The study aims at investigating the characteristics of

female DiDIYers, and in particular their personal

traits, roles, goals and mindsets. The investigation of

their work environment takes on a particular

importance in shaping their mindset. Thus the

research questions are:

is there a female approach to digital technology

and DiDIY?

are there personal and organizational (i.e.

workplace) characteristics that impact on

women’s attitude towards DiDIY?

what is the female DiDIYers’ profile and

mindset?

3 SAMPLE, METHODOLOGY

AND RESEARCH TOOLS

The study involved a sample of women working in

the Municipality of Milan and its agencies, at LIUC

University (a small University located in North Italy)

or associated to a well-known female membership

corporation (Valore D).

The Municipality of Milan is one of the largest

local public administrations in Italy. It employs

14,478 employees (as of 31 December 2016), among

them 64% are women and 5% work in its agencies.

Nevertheless only 38% women cover managerial

roles, revealing the persistence of a glass ceiling

phenomenon. Its organizational structure is a modern

bureaucracy involved in an important digital change

process. The University is a non-state entity focused

on the teaching of managerial disciplines.

Administrative staff is predominantly composed of

women (73,7%), while men prevail in the academic

staff: among them just 30,2% are women. Valore D is

the most relevant Italian Association whose mission

is to promote women’s leadership in the corporate

world. It aims at increasing women’s representation

in top positions in major Italian companies through

tangible and concrete actions. Their members are

represented by about 150 large companies. It is

significant that the Association's headquarters are at

the premises of the Talent Garden, a global network

of digital innovators.

For the purposes of the research the most effective

tool of analysis was an on-line survey because it

allowed the collection of a large amount of data

overcoming time and distance problems.

The questionnaire developed for the on-line

survey was organised in five thematic macro-areas

concerning personal references, professional

experience, digital literacy, attitudes towards digital

technologies and approach to DiDIY.

Women were invited to participate in the survey

by e-mail. Data collection took place from April to

July 2017, and a large amount of responses was

obtained. On the whole, the survey gathered 591

questionnaires; 492 filled in by women working in the

public sector, specifically in the Municipality of

Milan. Even if the sample is not statistically

representative, it provides a meaningful picture of

women’s skills, attitudes and expectations towards

digital technologies and DiDIY within the

Municipality of Milan.

The results of the survey were analysed through

quantitative methods.

KMIS 2018 - 10th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

188

Responses were statistically treated in different

ways, according to their nature (i.e. numbers,

categorical variables and ordinal variables).

4 DATA ANALYSIS

4.1 Profile and Mindset of the Sample

The sample comprises 591 Italian women, 83%

working at the Municipality of Milan. On average,

they are 49 years old, ranging from 25 to 64. The great

majority of them (69%) was born in Lombardy. Their

education level is highly differentiated: 44% of the

sample has a university degree (44%), 37% a

technical diploma, 12% a high school diploma.

Besides, some of them (14%) declare to participate

actively in some associations.

The job roles are diversified, both the function

and the hierarchical level. Among the most frequent

positions, 58% are employed in administrative roles,

16% in Human Resource Management and 13% in

Operations. Most of them (69%) work in a large

organization (more than 250 employees and 50

million turnover), which implies that they use to work

in a complex environment. Moreover, women

comprised in the sample generally work in team

(78%) and refer to a community of practice (35%).

Notwithstanding the complexity of the work

environment, their job context is mainly characterised

by informal coordination mechanisms. In particular

informal communication prevails (84%), followed by

the definition of the objectives to be achieved (42%).

On average the respondents rate their digital skills

2.8 out of 5, with 3 as median value. On the whole

they perceive themselves as moderately expert.

Most respondents acquired their digital skills

through field experience (56%), 21% are self-taught,

and only 13% had digital training. Thus they are

mainly self-motivated in developing their digital

skills. Hobbies and games are the main fields of

application of digital skills (18%), followed by

professional use of social media to coordinate

collaborators (8%) and marketing purposes (4%). It is

interesting to notice that not only women that apply

their digital competences for professional purposes

(use of social media in management, website

building, development of applications), but also those

who apply their digital skills for game purposes

reveal higher digital skills than average (3.2 out of 5).

Also in this female sample gamification plays an

important function in motivating people to acquire

digital skills (Hamari and Koivisto, 2015).

Women’s approach to digital technologies is

strongly characterised by assiduity, curiosity, aware-

ness, trust and reliance, whereas fear and constraint are

weaker. A factor analysis was carried out and revealed

a two-component solution (60% total variance explain-

ed, Varimax rotation). The components represent two

opposing attitudes towards digital technologies,

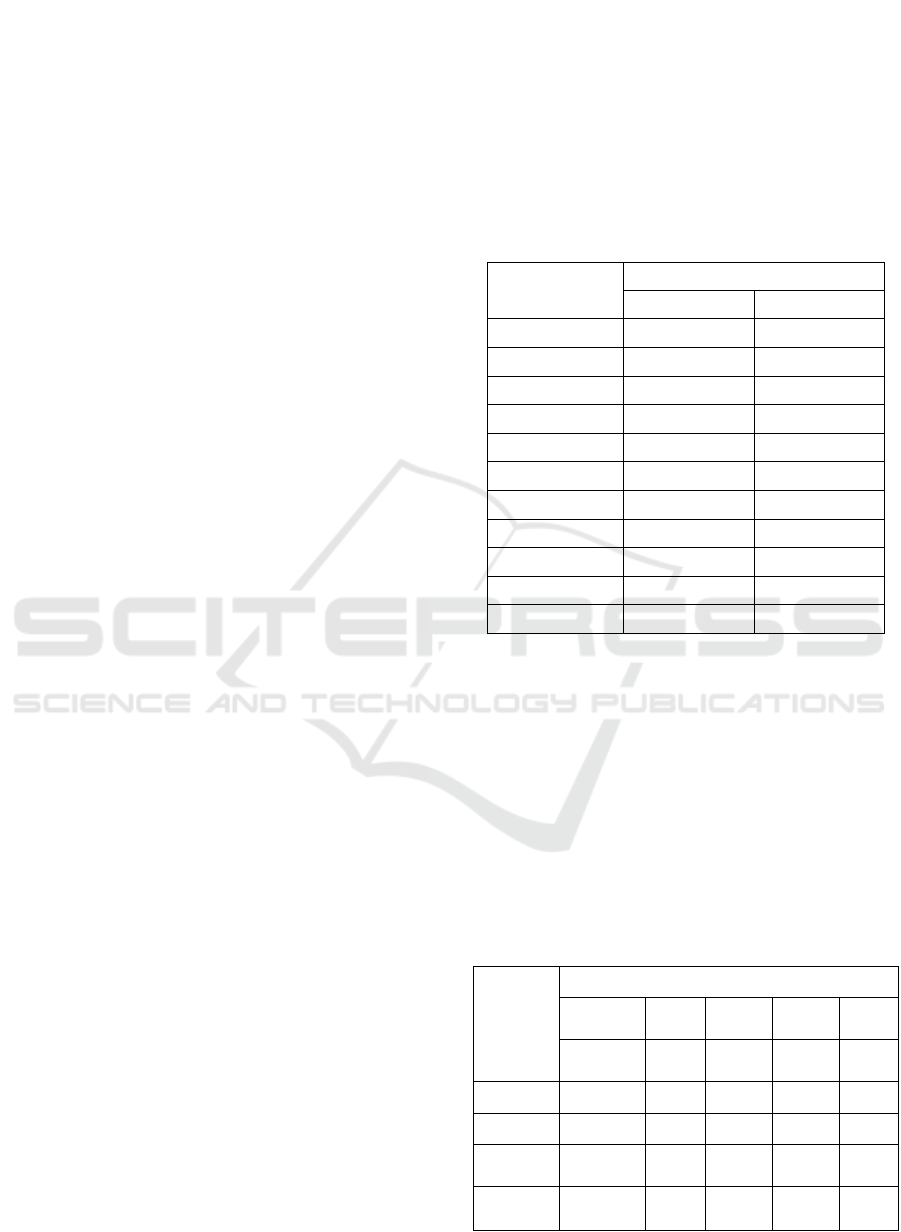

namely positive and negative attitudes (table 1).

Table 1: Rotated component matrix of attitudes towards

digital technologies.

Component

positive

negative

Pleasure

0.872

Passion

0.866

Curiosity

0.835

Assiduity

0.78

Innovativeness

0.769

Familiarity

0.768

Awareness

0.752

Reliance

0.648

Constraint

0.751

Fear

0.699

Adjustment

0.676

Then a regression analysis was carried out where

the dependent variables were the scores in the two

attitudes (positive and negative), and the predicting

variables included the age of the respondents, their

perceived level of digital skills and the size of the

organization they work in, considered an indicator of

organizational complexity. The results of the

regression analysis show that the perceived level of

digital skills is a predictor of a positive attitude,

whereas employee’s age and organizational

complexity are not significant (table 2).

Table 2: Regression coefficients for the positive attitude

towards digital technologies.

Coefficients

a

Unstand.

Coeff

Stand.

Coeff.

t

Sig.

B

Std.

Error

Beta

Constant

2.196

0.307

7.144

0.000

age

-0.007

0.004

-0.071

-1.680

0.094

digital

skills

0.497

0.036

0.556

13.890

0.000

org. size

0.035

0.087

0.017

0.402

0.688

a. Dependent Variable: positive attitude

Women and Technologies: Towards a Gendered Profile of Digital Do-It-Yourself Workers?

189

Following the results, organizations can pave the

way for digital transformation through employees’

digital skill reinforcement, almost regardless of the

average age of staff. This is quite important,

considering the need of organizations and public

administrations to successfully manage digital

change and the issue of workforce ageing.

Moreover, the fear of making mistakes does not

hinder the search for innovative solutions through

digital technology: fear seems to boost

innovativeness along with curiosity, especially

among DiDIYers, signalling that digital

experimentation cannot be without fear of making

mistakes but it is supported by digital skills.

The applications most used for any purpose by

women are in order of importance WhatsApp, Excel

and Facebook. These applications are preferred

because of their expected benefits in terms of

efficiency (time saving and cost reduction) and

effectiveness (readiness and quality of results)

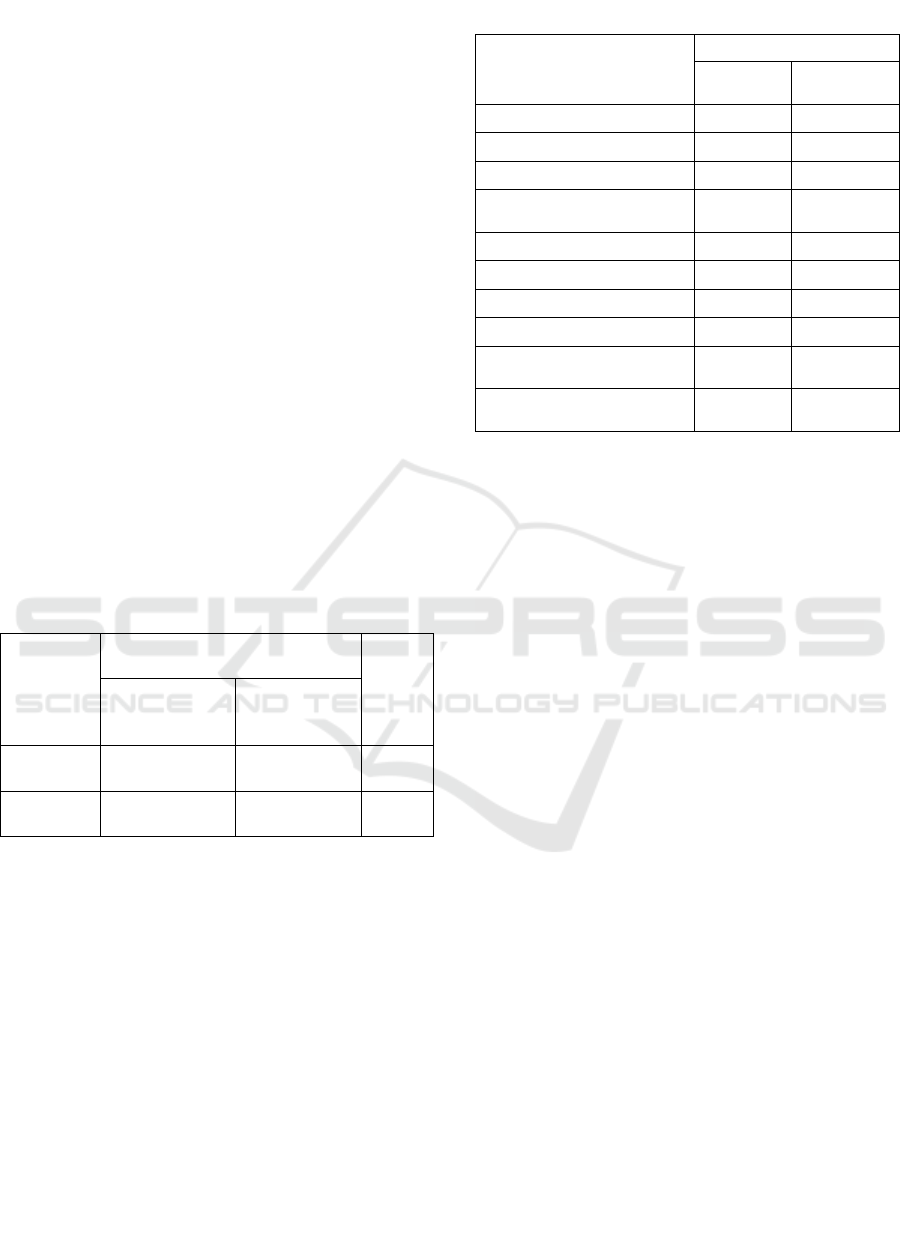

In any case, both in work and in social life, vis-à-

vis (traditional) relationships are preferred to

computer-mediated relationships (table 3). Human

contact remains a key component of effective

workplace relationships (Guerini and Minelli, 2018).

Table 3: Type of relationships preferred by women.

Context

Type of relationships

St.dev.

vis-à-vis

digital

technologies

work

55.5%

44.5%

19.9

social life

71.1%

28.9%

18.5

Women in the sample were also asked to indicate

their level of agreement (on a scale 1 to 4) to different

do-it-yourself (DIY) definitions. DIY is mostly

perceived as a “satisfaction” (3.7 out of 4), able to

develop skills and independence (3.3 out of 4), while

there is a low level of agreement (<1.6) on statements

defining DIY as “stuff for nerds”, “boring” or a

“waste of time”. The factor analysis carried out on the

results revealed a two-component solution (50% total

variance explained, Varimax rotation). The two

components are respectively usefulness and personal

and professional development (table4).

This result highlights how women perceive DIY

as a useful practice, able to develop personal

aspirations and professional skills.

Also for DiDIY women were asked to express

their level of agreement to some propositions defining

Table 4: Rotated component matrix of DIY perceptions.

Component

usefulness

develop-

ment

saves money

0.757

reduces waste

0.745

useful to find a job

0.633

combines technology and

art

0.554

a hobby

0.535

reassuring

0.478

a satisfaction

0.762

develops skills

0.727

helps to become

autonomous

0.691

realizes one's own

aspirations

0.551

this phenomenon. Women in the sample agree on

DiDIY as a fundamental tool for work, which

demonstrates an active use of technology (3.2 out of

4). Not only the respondents perceive the importance

of technology for their jobs but also, more generally,

“for the world”. DiDIY thus becomes an almost

salvific tool. In this case, all statements depreciating

DiDIY were rated lower that those supporting it.

4.2 DiDIYers’ Profile and Mindset

Among the respondents, a group of 38 women stands

out: those women have developed new digital

applications and in 32 cases they have realized them

too. Those female DiDIYers that are at the core of this

study. Slightly younger than the whole sample (48

years old), most DiDIYers were born in Lombardy

(58%) and as many as 60% have a degree or a higher

education level. The large majority (71%) is

employed in the Municipality of Milan, they use to

work in team (82%) and quite frequently refer to a

community of practice in their professional activity

(39%). Female DiDIYers perceive themselves as

experts (3.6 out of 5).

Comparing them with the whole sample, a higher

percentage of DiDIYers had specific training in

digital skills (21%), whereas 42% acquired their skills

thanks to field experience or is self-taught (18%).

Nonetheless, similarly to the whole sample, the most

part of them (60%) are self-motivated in developing

their digital skills, even at a higher level of skill.

However, in this DiDIYers’ sample the main purpose

of digital skills application is professional use (39%),

followed by apps development (26%) and website

KMIS 2018 - 10th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

190

building (16%) whereas hobbies and games represent

only a marginal purpose.

Among DiDIYers, 16% is employed in the

Information Technology function and 18% in the

Marketing and Customer Care functions. That reveals

a first interesting result regarding the concentration of

DiDIYers: DiDIYers are not uniformly present in all

functions. The areas where women DiDIYers are

mostly present are those related to technology

(information technology and research & development)

or strictly connected to the external environment

(customer service and marketing). This outcome

suggests that some kinds of activities stimulate and

require a DiDIY attitude, in particular those connecting

the organization with its environment.

Depicting their approach to digital technologies in

their work and personal lives, women DiDIYers

evaluated awareness, curiosity and innovativeness

higher than the other items and feelings proposed and

higher than the scores of the whole sample as well. This

shows that awareness is an important indicator of

digital literacy and that - together with curiosity and

innovativeness - it represents a driver of expertise and

a motivator of digital improvement (Gallardo-

Echenique et al., 2015).

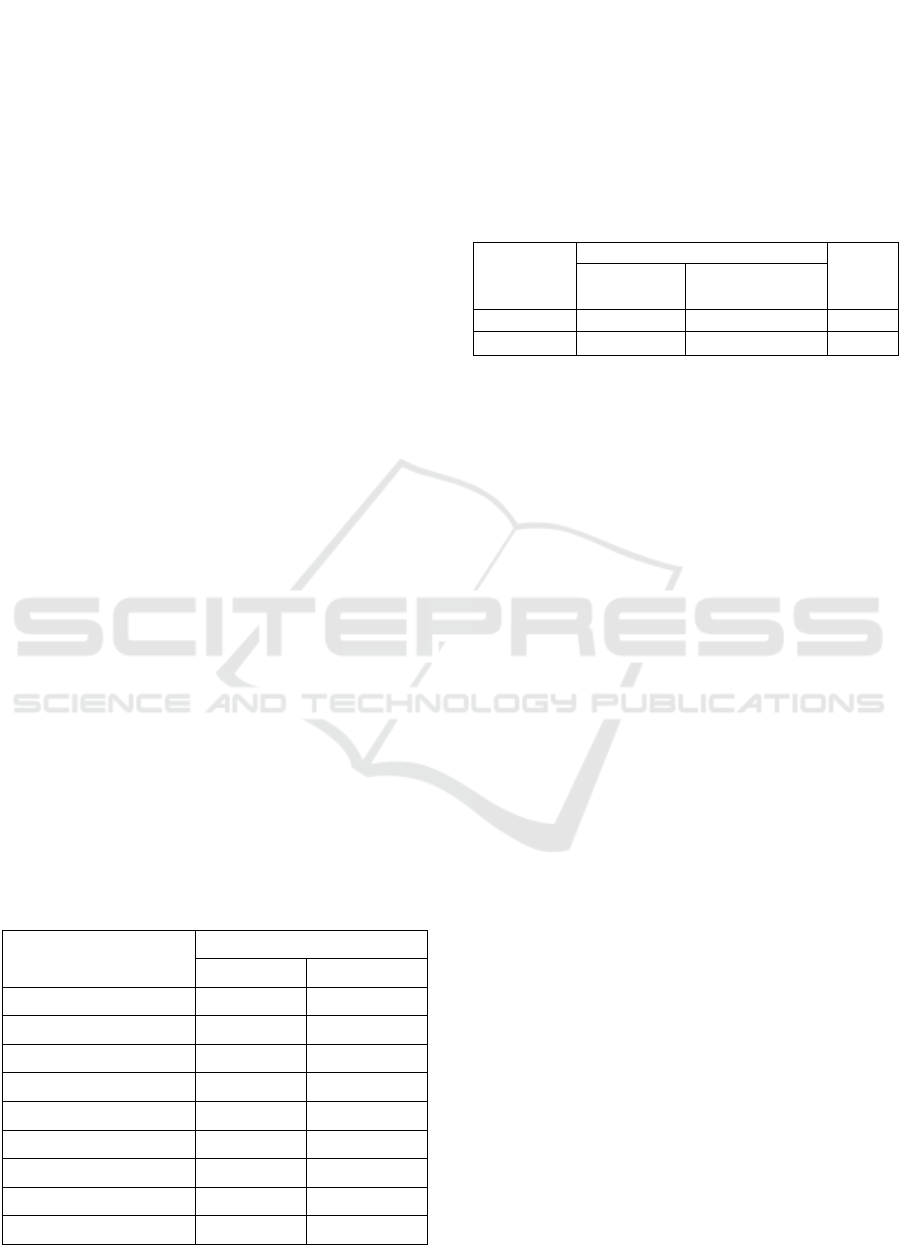

Moreover, passion and pleasure (respectively 3.7

and 3.6 out of 5) demonstrate that women DiDIYers

are not only technology adopters but above all expert

amateurs (Kuznetsov and Paulos, 2010). The factor

analysis carried out revealed a two-component solution

(68% total variance explained, Varimax rotation). The

components are represented in this case by the

meanings that the digital technologies take on for

female DiDIYers, namely innovation and reliability

(table 5). Thus, in this case the components are not

represented by dichotomic perception (positive and

negative) of the value of digital technologies as for the

Table 5: Rotated component matrix of women DiDIYers’

attitudes towards digital technologies.

Component

innovation

reliability

Innovativeness

0.863

Curiosity

0.851

Passion

0.825

Pleasure

0.795

Familiarity

0.507

Assiduity

0.881

Awareness

0.753

Adjustment

0.736

Reliance

0.600

whole sample, but by a deeper awareness of the impact

of digital technologies on their lives.

Notwithstanding their digital skills, women

DiDIYers’ propensity to vis-à-vis relationships is

similar to the whole sample both in work and social

life, pointing out that the human touch is predominant

in social life and cannot be replaced by virtual

relations (table 6).

Table 6: Type of relationships preferred by women.

Context

Type of relationships

St.dev

.

vis-à-vis

digital

technologies

work

55.8%

44.2%

21.0

social life

69.0%

31.0%

20.5

Most of them used software for the creation and

management of websites and blogs or for the

realization of digital videos; some also used 3D

printers and scanners, and a few made use of

electronic prototyping cards (such as Arduino,

RaspberryPi, etc.). In general, female DiDIYers think

that there is still a lot to do in the field of digital

applications for professional use (89%), in particular

for relational and technical purposes. In fact, 26% of

them developed, and in some cases even realised

applications devoted to the improvement of

coordination and collaboration, for control purposes

(26%), to improve efficiency (26%) and 11% to

improve effectiveness.

In their digital activities they are not motivated

just by curiosity or game: women DiDIYers are

pushed also by innovation, personal intuition and

experimentation (26%) and, above all, by

professional challenges (60%). Therefore, in this

sample women reveal that as their digital literacy

grows, they are less motivated by ludic aims and

increasingly by innovation purposes and professional

challenges.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The study investigates women’s approach to digital

technologies and DiDIY, outlining personal and

organizational characteristics that impact on

women’s attitude towards DiDIY.

The sample includes 591 female respondents; a

part of them can be defined as DiDIYer because they

declare to have developed and, partly, realized new

digital applications. Women in the sample are mature

and educated and, among the DiDIYers, as many as

60% have a degree or a higher education level.

Women and Technologies: Towards a Gendered Profile of Digital Do-It-Yourself Workers?

191

The sample comprises mostly women working in

large organizations in various roles. Their

organizations are characterised by complexity,

though informal coordination mechanisms based on

direct communication are widespread and overlap to

almost all other mechanisms (rules, procedures,

objectives etc.). Thus, complexity does not

necessarily combine with high formalization; on the

contrary, there is room for direct communication and

human contact. Moreover, women mostly work in

teams and some of them refer to a community of

practice in her job, underlying the importance of

professional links, both within and outside the

organization. This trait is amplified among the female

DiDIYer, concentrated in a few organizational areas,

and in particular in those functions that connect the

organization to the external environment, such as

Research and Development, Marketing and Customer

Service. Thus, organizational complexity and

connections with the external environment are the

emerging characteristics of the female DiDIYers’

workplace. Knowledge sharing and creation within

organic and participative cultures, also through

communities of practice, are also important features.

In the sample women perceive themselves, on

average, as moderately expert, whereas the DiDIYers

rate their digital expertise as higher, even if all declare

to have acquired their digital skills mainly through

field experience and self-training. Therefore, self-

motivation appears to be an important driving force

in developing digital skills. It’s interesting to notice

that not only women that are engaged in technological

activities, but also those who apply these abilities for

recreational goals declare a higher level of digital

expertise than average, showing that gamification

plays an important role in acquiring digital skills and

that it can be a successful tool in training people in

large organizational contexts. However when it

comes to DiDIY activities, game is no longer a driver:

female DiDIYers are pushed also by innovation,

personal intuition and experimentation and, above all,

by professional challenges. Therefore this study

suggests that gamification can play an important role

in approaching digital technologies and training basic

digital skills, but at a higher level of competences

gives way to other levers, in particular to the appeal

of innovation and personal and professional

challenges.

Women in the sample consider digital

technologies as an almost salvific tool. In more

details, female DiDIYers describe their attitude

towards digital technologies with the concepts of

awareness, curiosity and innovativeness, confirming

that the awareness of being a digital expert is a

fundamental trait of DiDIYers. Moreover, passion

and pleasure demonstrate that women DiDIYers are

not only technology adopters but above all expert

amateur (Kuznetsov and Paulos, 2010).

In more details, the regression analysis highlights

that the perceived level of digital skills is a predictor

of a positive attitude towards digital technologies

whereas staff’s age and organizational complexity

aren’t. This result shows that organizations - and

public administration as well - can favour digital

transformation through their employees’ digital skills

training and manage a successful transition even

within a context of workforce ageing. In any case, so

far, personal and traditional relationships are

preferred to virtual computer-mediated ones, even

among DiDIYers. In this sense the human contact is

probably an irreplaceable component of wellbeing,

both in the workplace and in social life and no

substitution effects of digital technologies on human

relationships is accepted or expected.

Finally, female DiDIYers’ mindset is that of

passionate people, emotionally involved, educated

and aware of the high value of DiDIY outputs. At the

same time, they are proud and conscious of their

potential contribution to the improvement of their

lives and their workplace. In their opinion the

developing technology feeds on creative experimen-

tation and becomes almost a vision of the world.

This study aims at advancing the knowledge of

the DiDIY phenomenon in the gender domain.

However, it has several limitations They include

issues related to: (a) sampling, (b) participants’ level

of honesty and accuracy; (c) the study was also

limited to one country (Italy) and (d) mainly big

public corporations. Nonetheless, the study

contributes to shedding some light on the relation

women-technologies and, moreover, on the existence

and the actual characteristics of female DiDIYers in

complex organisation.

The results acknowledge some distinctions

between female workers and female DiDIYers,

outlining the emerging characteristics of the female

DiDIYers’ profile. Nevertheless, our research does

not outline gender-related differences. Further

research comparing men and women working within

the same organizations could outline those

differences. The study suggest that DiDIY might have

a direct impact on firms’ performance. A deeper

knowledge of the phenomenon within the functional

areas where it is concentrated would enable insight

(Anwar, et al., 2017; McDonald, 2017) on how

organizations can engage female employees in

DiDIY to improve performance and workers’

satisfaction.

KMIS 2018 - 10th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

192

REFERENCES

Anderson, C., 2012. Makers: The new industrial revolution.

New York, NY: Random House.

Anwar, M. et al., 2017. Gender difference and employees'

cybersecurity behaviors. Computers in Human

Behavior, pp. 437-443.

Butler, J., 2004. Undoing Gender. New York: Routledge.

Buxmann, P. & Hinz, O., 2013. Makers. Business &

Information Systems Engineering, 5(5), pp. 357-360.

Cremona, L. & Ravarini, A., 2016. Digital Do-It Yourself

in work and organizations: Personal and

environmental characteristics. Verona (Italy).

Digital DIY, 2017. DiDIY Digital Do It Yourself [Online]

Available at: http://www.didiy.eu [Accessed 21

February 2017].

Edwards, C., 2006. Home is where the art is: Women,

handicrafts and home improvements 1750 – 1900.

Journal of design history, 19(1), p. 11–21.

Eriksson-Zetterquist, U., 2007. Editorial: gender and new

technologies. Gender, Work & Organization, 14(4), pp.

305-311.

Gallardo-Echenique, E. E., Minelli de Oliveira, J.,

Marqués-Molias, L. & Esteve-Mon, F., 2015. Digital

Competence in the Knowledge Society", , Vol. 11 No.

1, pp. 1-16.. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and

Teaching, 11(1), pp. 1-16.

Guerini, C. & Minelli, E., 2016. Knowledge-Oriented

Technologies & Network Marketing Direct Selling

Organizations (NMDSO) - Some Preliminary Insights

into the Nature and the Goals of Shared Knowledge.

s.l., SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology

Publications, Lda., pp. 301-306.

Guerini, C. & Minelli, E. A., 2018. The subjective side of

DiDIY: the profile of makers in network marketers

communities. Data Technologies and Applications.

Halford, S. & Savage, M., 2010. Reconceptualizing digital

social inequality. Information, Communication &

Society, 13(7), pp. 937-955.

Hamari, J. & Koivisto, J., 2015. Why do people use

gamification services?. International Journal of

Information Management, 35(4), pp. 419-431.

Hoftijzer, J., 2009. DIY and Co-creation: Representatives

of a Democratizing Tendency. Design Principles &

Practices, An International Journal, 3(6), pp. 69-81.

Kuznetsov, S. & Paulos, E., 2010. Rise of the Expert

Amateur: DIY Projects, Communities, and Cultures.

s.l., ACM New York, NY, USA, pp. 295-304.

Lovejoy, K. & Saxton, G. D., 2012. Information,

Community, and Action: How Nonprofit Organizations

Use Social Media. Journal of Computer-Mediated

Communication, 17(3), pp. 337-353.

Mari, L., 2014. Toward the first version of the Knowledge

Framework (D2.3) - V2, 2. KF Pillars. [Online]

Available at: https://goo.gl//km3KfC[Accessed 27 July

2016].

Oh, O., Agrawal, M. M. & Rao, H., 2013. Community

Intelligence and social media services: a rumor

theoretical analysis of tweets during social crisis. MIS

Quarterly, 37(4), pp. 407-426.

Ravarini, A. & Strada, G., 2018. From smart work to Digital

Do-It-Yourself: a research framework for digital-

enabled jobs. In: R. Lamboglia, A. Cardoni, R. P.

Dameri & D. Mancini, eds. Network, Smart and Open.

Lecture Notes in Information Systems and

Organisation. s.l.:Springer, Cham, pp. 97-107.

Roomi, M. A., 2009. Impact of social capital development

and use in the growth process of women-owned firms.

Journal of Enterprising Culture, 17(4), pp. 473-495.

Wajcman, J., 2007. From women and technology to

gendered technoscience. Information, Communication

& Society, June, 10(3), pp. 287-298.

Women and Technologies: Towards a Gendered Profile of Digital Do-It-Yourself Workers?

193