Assessment of Generic Skills through an Organizational Learning

Process Model

Antonio Balderas

1

, Juan Antonio Caballero-Hern

´

andez

2

, Juan Manuel Dodero

1

,

Manuel Palomo-Duarte

1

and Iv

´

an Ruiz-Rube

1

1

Department of Computer Science, Universidad de C

´

adiz, Av. de la Universidad de C

´

adiz 10, Puerto Real, Spain

2

EVAL for Research Group, Universidad de C

´

adiz, Av. Rep

´

ublica

´

Arabe Saharaui s/n, Puerto Real, Spain

Keywords:

Knowledge Management System, Life-Long Learning, Generic Skills Assessment, Learning Management

System, Learning Analytics, Model-driven Architecture, REST Web Service.

Abstract:

The performance in generic skills is increasingly important for organizations to succeed in the current com-

petitive environment. However, assessing the level of performance in generic skills of the members of an

organization is a challenging task, subject to both subjectivity and scalability issues. Organizations usually

lay their organizational learning processes on a Knowledge Management System (KMS). This work presents a

process model to support managers of KMSs in the assessment of their individuals’ generic skills. The process

model was deployed through an extended version of a learning management system. It was connected with

different information system tools specifically developed to enrich its features. A case study with Compu-

ter Science final-year students working in a software system was conducted following an authentic learning

approach, showing promising results.

1 INTRODUCTION

Lifelong Learning is generally defined as the educa-

tional activities that individuals have been involved

during their lives (Ozdamli and Ozdal, 2015), invol-

ving learning experiences that take place at home, in

the workplace, in universities and colleges, and in ot-

her educational, social, and cultural agencies, institu-

tions, and settings, both formal and informal (Aspin

and Chapman, 2007). Lifelong Learning in the work-

place is a key factor for the success of companies,

since today’s competitive environment requires pro-

fessionals in any field to continuously improve their

skills in order to face new challenges in their area of

knowledge (Gagnon et al., 2015; Hennekam and Ben-

nett, 2017).

In this context, the demand of employees on com-

panies has shifted its focus from knowledge to skills

(Crebert et al., 2004). Competencies can be divi-

ded into subject-specific and generic (Andrews and

Higson, 2008). While subject specific competencies

are related to knowledge in the subject areas, ge-

neric competencies are the abilities, capacities and

knowledge that any person should develop regard-

less of his/her subject area. Generic skills compe-

tence is relevant for organizations, and future gradua-

tes are preparing at universities to meet labour market

needs (Fit

´

o-Bertran et al., 2015; Edwards-Schachter

et al., 2015). As a result, the strategic management

has to focus on the internal capabilities of organizati-

ons in order to strategically align its human resources

with employee capabilities (Svetlik et al., 2007; Hu-

ang et al., 2016). In organizations, generic skills such

as leadership or teamwork are usually key to consider

the most suitable candidate for a position (Nita et al.,

2016). However, objectively determining the level of

performance in generic skills of every member of an

organization is a challenging task. This work beco-

mes even more demanding for large-sized organizati-

ons, where the number of workers interacting can be

really high.

The competence of an organization can be enhan-

ced adding organizational learning to the relations-

hip between knowledge transfer and dynamic com-

petence (Huang and Guo, 2010). Organizational le-

arning is the process by which an organization incre-

ases the knowledge created by individuals in an or-

ganized way and transforms this knowledge into part

of the knowledge organization system. The process

takes place at an individual level, at a group level

and at a system organization level (Reese and Hunter,

2016), having a positive influence both organizational

Balderas, A., Caballero-Hernández, J., Dodero, J., Palomo-Duarte, M. and Ruiz-Rube, I.

Assessment of Generic Skills through an Organizational Learning Process Model.

DOI: 10.5220/0006960802930300

In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST 2018), pages 293-300

ISBN: 978-989-758-324-7

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

293

performance and organizational innovation (Garc

´

ıa-

Morales et al., 2012).

To support organizational learning, medium or

large size organizations usually rely on a Knowledge

Management System (KMS). KMSs provide organi-

zations with different advantages in terms of com-

munication, learning, sharing information, informa-

tion retrieval and learning functions integration (Lie-

bowitz and Frank, 2016). Unfortunately, KMSs do

not usually provide managers with objective indica-

tors about the generic skills performance of their in-

dividuals (i.e. staff).

A Learning Management System (LMS) is a web-

based virtual educational environment with different

modules to support learning processes. LMSs are

commonly used in educational centres at all levels and

can also be considered as KMS tools (Abu Shawar

and Al-Sadi, 2010). In a LMS, supervisor can ana-

lyze learning situations by collecting interaction re-

cords produced by these environments (Chebil et al.,

2012; Fidalgo-Blanco et al., 2015b).

Thus, can learning records in a KMS be used as

evidences to automate the assessment process of in-

dividuals’ performance in generic skills? This paper

proposes a process model ultimately aimed at asses-

sing the acquisition of certain skills by using a KMS

built on top of a LMS and a set of dedicated tools

published under open-source license. This process

and these tools facilitate both the manual assessment

of generic skills linked to evidences and the automa-

tic extraction of objective indicators for those skills.

To test the process model, a case study assessing se-

veral generic skills of individuals is conducted, sho-

wing promising results.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews the background. Section 3 intro-

duces the proposed process. Section 4 presents the

set of tools implemented. Section 5 describes a case

study about the assessment of several generic skills

through an authentic learning experience. Finally, in

the last section, we provide a discussion along with

conclusions and future research lines.

2 BACKGROUND

In the current competitive context, knowledge mana-

gement process within organizations aims to enhance

both their individuals and group skills. Some generic

skills, such as teamwork or planning and time mana-

gement, are fundamental for individuals’ job perfor-

mance and, consequently, the successes of the organi-

zation (Ahmad et al., 2012; Burt et al., 2010).

Thus, this knowledge management process is usu-

ally embedded in virtual learning frameworks. A

study focused on building students’ engagement in

virtual courses demonstrated that the main reason for

the high withdrawal rate was the participants’ poor

time management skill (Nawrot and Doucet, 2014).

In this context, the Adaptive Semantic Web is a

framework that enables skill-based customization of

Web resources, including learning scenarios (Paquette

et al., 2015). In that work, learners were automati-

cally clustered into subgroups by their skills. These

clusters were more suitable to foster collaboration and

to adapt scenarios according to the cluster members’

needs. Unfortunately, the author claims that the mo-

del was not simple to implement, and students’ skills

identification should be at least partly automated con-

sidering that a human tutor approach is not feasible

for large groups.

Organizational learning is defined as the ability

of an organization to gain insight and understan-

ding from experience through experimentation, ob-

servation, analysis and a willingness to examine both

successes and failures (Sch

¨

on and Argyris, 1996).

Companies that build structures and strategies in or-

der to increase and maximize the organizational le-

arning are distinguished as learning organizations.

In (Abel and Leblanc, 2009), organizational learning

is subdivided into three sub processes: Individual Le-

arning Process, Social Process and Knowledge Mana-

gement Process. Then, they are incorporated into E-

MEMORAe2.0 tool, designed for knowledge sharing

in an organizational learning context. A fully exploi-

tation of the traces in E-MEMORAe2.0 tool was used

to organize and improve collaboration (Wang et al.,

2015). Besides, the authors proposed a recommender

system based on the assessment of traces considering

the time decay of knowledge.

Organizations are using KMSs to facilitate kno-

wledge sharing. The way of interacting and sharing

knowledge depends on individuals’ skills and charac-

teristics. A experiment demonstrated that individuals’

perseverance in the tasks given and responsibilities ta-

ken positively influence their commitment with kno-

wledge sharing (Wang et al., 2014). LMSs also sup-

port the management of learning processes within or-

ganizations, enabling peer-to-peer knowledge capture

and sharing in a knowledge-based organization (Kline

et al., 2017). A LMS can manage all aspects of or-

ganizational learning alleviating the knowledge crea-

tion.

Assessment instruments are applied by organizati-

ons to measure their individuals’ skills. Bohlouli et al

defined a standard competence model with five main

skill categories and related sub-categories including

over 70 skill questionnaires in different managerial

WEBIST 2018 - 14th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

294

and employee levels (Bohlouli et al., 2013). Some of

these instruments and models are well known and wi-

dely used by organizations. Unfortunately, the moni-

toring and assessment process of each learner through

these instruments requires assessors to perform a sig-

nificant effort (Fidalgo-Blanco et al., 2015a), so ap-

plications based on learning analytics are needed to

alleviate the assessment process.

According to Siemens’ definition, learning ana-

lytics is the use of intelligent data, learner-produced

data, and analysis models to discover information and

social connections, and to predict and advise on lear-

ning (Siemens, 2010). Students’ performance in ge-

neric skills have been assessed through the collection

of students’ activity records with LMSs by means of

software based on learning analytics (Balderas et al.,

2018).

3 ORGANIZATIONAL

LEARNING PROCESS

With the objective of providing answers to the requi-

rements of training and knowledge assessment in an

organizational environment, we propose the process

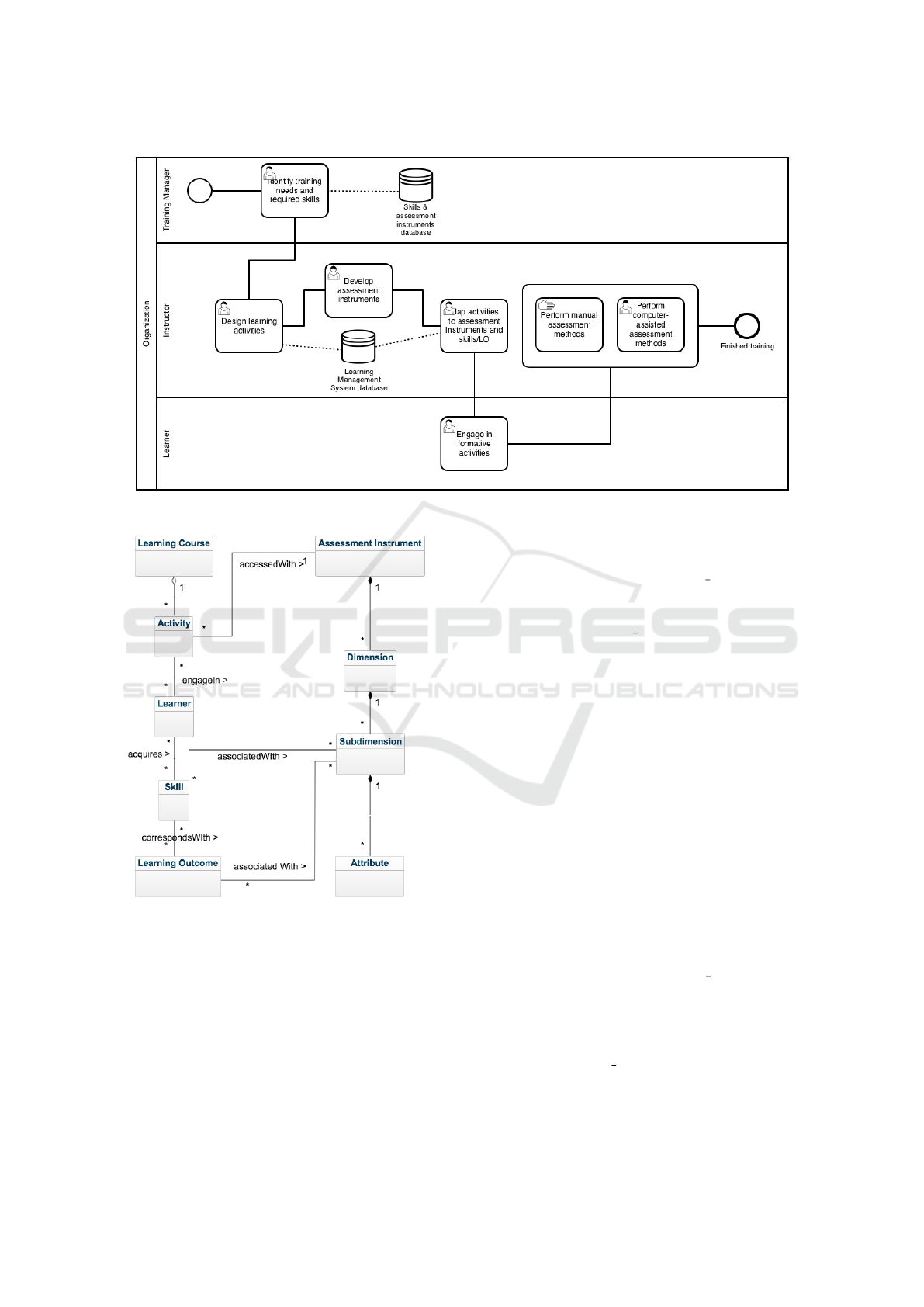

model shown in Figure 1. This process model in-

cludes several roles and both manual and computer-

assisted activities. All of these are aimed at the acqui-

sition and assessment of the participants’ skills in trai-

ning activities of a given organization. The process

model comprises the following sequence of activities:

1. Identification of Training Needs and Required

Skills: First, the manager in charge of organizatio-

nal learning within the organization identifies the

learning needs. Second, he/she designs a specific

learning plan. This plan lists the catalog of skills

expected for all learners. The manager maintains

the catalog of the skills and learning outcomes for

the organization by using a specific tool.

2. Design of Learning Activities: Subsequently, the

manager designs the learning activities needed for

the training plan by using the features of a KMS.

This way, he/she is able to monitor the learning

activities that learners are engaging.

3. Deployment of Assessment Instruments: By using

e-assessment systems, detailed feedback-enriched

assessment of learners can be supported.

4. Mapping Activities to Assessment Instruments and

Skills/Learning Outcomes: A conceptual model

containing the elements of interest involved in

this mapping is depicted in Figure 2. This mo-

del includes assessment instruments structured in

dimensions and sub-dimensions. Once the asses-

sment instruments have been deployed, the ma-

nager should indicate the skills and learning out-

comes that are developed by the learners through

learning activities. Then, it is necessary to make

a mapping among the involved activities, the sub-

dimensions of the assessment instruments, and the

skills and outcomes.

5. Engagement in Formative Activities: After setting

up the learning environment and the needed con-

figurations for the assessment, the training activi-

ties in which the learners are involved are carried

out.

6. Performing Manual Assessment Activities: The

manager has to proceed with the assessment by

analyzing the learning results generated by lear-

ners. To perform this step, the manager uses the

assessment instruments previously created accor-

ding to the required skills.

7. Performing Computer-assisted Assessment Activi-

ties: The analysis of the learning results generated

by the learners may be partially assisted by using

specific tools developed for those purposes.

4 IMPLEMENTATION

To support the organizational learning process propo-

sed, a set of tools were used, some of them specifi-

cally developed under open-source license:

• Moodle Learning Management System to design

learning activities (activity 2).

• EvalCOMIX to develop assessment instruments

(activity 3). Available in (EvalComix, 2011).

• Gescompeval to map activities to assessment in-

struments and skills/learning outcomes (activity

4). Available in (Gescompeval, 2014).

• EvalCourse to perform a computer-assisted as-

sessment based on learning analytics (activity 7).

Available in (EvalCourse, 2015).

The following subsections present these tools.

4.1 Learning Management System

To design learning activities, we have opted for using

Moodle as a LMS, a very popular and widespread

open source web-based system (Rice, 2006). We cre-

ated some specific tools to enrich Moodle with ma-

naging assessment instruments, managing skills and

analyzing learning activities by extracting desired in-

dicators.

Assessment of Generic Skills through an Organizational Learning Process Model

295

Figure 1: Organizational process model for the assessment of acquired skills.

Figure 2: Conceptual model containing the main elements

of interest in the KMS.

4.2 EvalCOMIX

We used EvalCOMIX to carry out the e-assessment

activities in our architecture. It is a web service spe-

cifically designed to develop and manage different as-

sessment instruments such as scales or rubrics. Each

assessment instrument has its own structure based on

dimensions, sub-dimensions and attributes.

EvalCOMIX provides an API that can be integra-

ted with other e-learning systems to use designed as-

sessment instruments (S

´

aiz et al., 2010). Therefore,

a specific block called EvalCOMIX MD was imple-

mented to integrate EvalCOMIX with Moodle. As

other Moodle blocks, it is implemented in PHP and

JavaScript. EvalCOMIX MD provides three learning

assessment methods to be included in Moodle acti-

vities: teacher assessment, self assessment and peer

assessment.

4.3 Gescompeval

We developed Gescompeval to manage skills and le-

arning outcomes in the proposed architecture. It

is a REST web service which provides a read-only

API to retrieve these skills and learning outcomes.

Gescompeval includes a web interface to handle ba-

sic CRUD (Create, Read, Update, and Delete) ope-

rations and to connect skills to learning outcomes

(and vice versa). Both API and web interface fol-

low a model-view-controller (MVC) architecture im-

plemented Symfony2, a PHP framework.

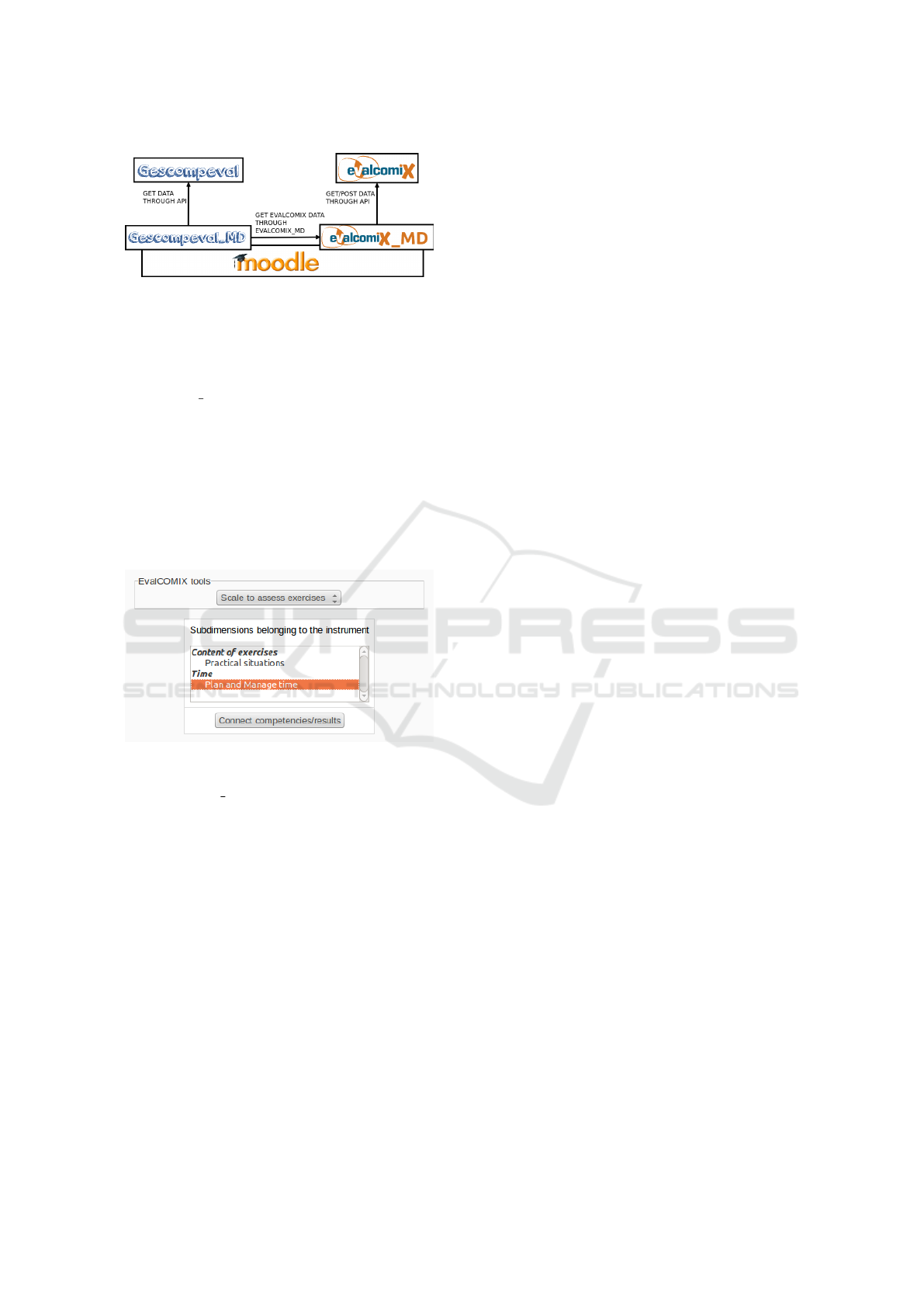

The integration of Gescompeval into Moodle was

carried out through the development of a Moodle 2.X

block extension called Gescompeval MD. This block

uses Gescompeval REST API to retrieve skills and

learning outcomes data in Moodle courses. Then,

this information can be connected to activities and as-

sessed applying EvalCOMIX assessment instruments

through EvalCOMIX MD. The overall integration ar-

chitecture between EvalCOMIX, Gescompeval and

Moodle is displayed in Figure 3.

The integration of EvalCOMIX and Gescompeval

WEBIST 2018 - 14th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

296

Figure 3: Skill management and e-assessment architecture.

with Moodle supports the assessment of specific skills

and learning outcomes for each learner and the com-

pilation of their grades. First, instructors have to se-

lect the required skills or learning outcomes by using

Gescompeval MD interface and then, they link them

to the corresponding sub-dimension of their EvalCO-

MIX tools. We display an example of this connection

in Figure 4. Second, skills/learning outcomes get the

grades from the sub-dimensions they are connected

with and combine those grades to get the overall grade

of their dimension. Finally, the grades for each skil-

l/learning outcome are displayed in a report to pro-

vide formative feedback. These reports are dynamic

graphics developed using Google Charts.

Figure 4: Selection of sub-dimension snapshot.

Gescompeval MD provides two types of feedback

reports. On one hand, a global report of all learners

who participate in the course is provided. This re-

port calculates the average grade of all learners’ gra-

des. On the other hand, individual reports with the

grades of each learner are also provided. Both re-

ports include an option to select if existing connecti-

ons between skills and learning outcomes must be ta-

ken into account to calculate the grades. Additional

information is displayed through a pop-up window

when users place the mouse pointer over a skill/le-

arning outcome graphic. This information includes:

code, name, value and those activities where the skil-

l/learning outcome were developed.

4.4 EvalCourse

Finally, we used EvalCourse, a standalone application

based on learning analytics that we developed to pro-

vide instructors with reports about students’ interacti-

ons with the LMS. EvalCourse was developed follo-

wing the model-driven architecture (MDA) methodo-

logy, to deal with concepts of an educational dom-

ain model. In particular, it executes queries coded in

SASQL, a domain specific language to easily design

online learning assessment on students’ generic skills

based on their interactions with LMSs (Balderas et al.,

2015), providing several reports with the information

required.

EvalCourse supports two different configurations.

Firstly, it can be directly connected to the LMS da-

tabase. This is the desired operation mode, because

reports are based on live updated information. Unfor-

tunately, sometimes is not possible to obtain permis-

sion to establish a connection with the database of an

institutional LMSs. In these cases, it can work with a

backup of a LMS course, i.e. a snapshot of the records

of a course in a given moment.

5 CASE STUDY

This case study follows an authentic learning appro-

ach (Lombardi, 2007) in order to promote students to

explore, discuss and construct products in real-world

projects. In our case, this experience simulates a I.T.

company where employees in a project had to develop

a software system. The employees were six students

of Computer Science degree in their fifth (final) year.

They had to fulfill several milestones, each one with a

software deliverable for a certain deadline.

During their development tasks, they had to per-

form several generic skills. In this case study, the in-

structor posed tasks in which students should perform

the following skills: (a) ability to work autonomously,

and (b) ability to plan and manage time.

Then, students’ performance in those generic

skills were assessed following both the manual and

the computer-assisted methods within the organizati-

onal learning process proposed.

5.1 Manual Assessment

The instructor defined two assessment instruments

thorough EvalCOMIX, containing a dimension for

each generic skill. Each deliverable was assessed with

four attributes: correctness, efficiency, speed of exe-

cution and applied knowledge. They were assessed in

a scale of: none (one or no deliverable has the attri-

bute), some (at least two deliverables have it) and all

(every deliverable has it). Additionally, submission

time was assessed with one single attribute with four

values: delayed (submitted after deadline), average

Assessment of Generic Skills through an Organizational Learning Process Model

297

planning (submitted one or two hours before dead-

line), good planned (submitted one day before dead-

line) and excellent planning (more than two days be-

fore deadline).

Then, while students delivered their pieces of soft-

ware, the instructor assessed not only the technical

work well or badly done (specific skills), but also their

planning and their ability to work autonomously by

using Gescompeval.

5.2 Computer-assisted Assessment

Secondly, EvalCourse was applied in order to comple-

ment the former manual assessment. The first aspect

to analyze consists on checking if the students had de-

livered their assignments on time, delayed or even if

they had some pending assignment at the end of the

semester. The instructor can retrieve for that informa-

tion with the following SASQL code:

Evidence pieces_of_sw_delivered:

get students

show milestones

in assignment.

By using SASQL, the instructor can dynamically

redesign the query to or obtain information, contrast

an hypothesis and even check additional information

that can be used to assess a skill. For instance, the in-

structor detected that those students who delivered all

their pieces of software on time, had a greater number

of accesses to the LMS that the others. This informa-

tion was retrieved with the following SASQL code:

Evidence accesses_platform:

get students

show access

in campus.

Thus, the computer-assisted assessment gave the

instructor the opportunity to detect information about

students’ behaviour. This information was interesting

to assess one of the aimed skills and even some ad-

ditional ones. The following subsection discuss the

results obtained.

5.3 Discussion

Regarding the ability to plan and manage time, the

two assessments provide different approaches. On

the first hand, Gescompeval gives a better grade to

those students who submit their piece of software one

day before the deadline (good planned) or two or

more day before it (excellent planning). On the other

hand, EvalCourse gives the instructor a summary with

the number of pieces of software delivered, which of

them were delivered on time, and which of them were

not delivered. Figure 5 displays this comparison.

Figure 5: Comparison of both approaches for planning and

time management performance.

However, if we take into account Gescompeval re-

port for planning and time management and the acces-

ses to the campus obtained via EvalCourse, students’

numbers are more similar (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Comparison of students’ planning and time ma-

nagement with their accesses to the LMS.

It is important to highlight that the instructor could

assess other students’ generic skills not initially con-

sidered using EvalCourse reports. Figure 7 shows the

students’ grades in four generic skills performed by

the instructor with those reports: ability to plan and

manage time, capacity to learn and stay update with

learning, ability to be critical and self-critical and

ability to work autonomously.

Figure 7: Assessment of students’ skills via EvalCourse.

These assessments are interpretations that the in-

structor could assume with the obtained indicators,

but the validity of the application of these indicators

to a particular skill is outside the scope of this work.

We can conclude that the instructor could refine stu-

dents’ assessments with the objective indicators auto-

matically provided by EvalCourse. Actually, this is

WEBIST 2018 - 14th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

298

what concerns our proposal. To draw further conclu-

sions, this work requires deeper research, but it is a

valid first approach.

6 CONCLUSION

Although performance in generic skills is increa-

singly important for organizations to succeed in the

current competitive environment, its assessment in the

workplace remains as a challenging task.

In recent years, several alternatives to solve this is-

sue in educational contexts have been presented. Un-

fortunately, they rely on different activities that are

usually supported by isolated information systems. In

this paper, we have proposed a process model ultima-

tely aimed at automate the assessment of skills in a

KMS. We extended Moodle, a popular LMS, with a

set of specifically developed tools, such as Gescom-

peval, EvalCOMIX and EvalCourse.

The process model was tested by deploying a le-

arning experience to assess final-year undergraduate

students’ performance on several generic skills. The

experience was based on authentic assessment princi-

ples. On the one hand, the instructor mapped the acti-

vities to skills and performed the assessment by using

Gescompeval and EvalCOMIX. On the other hand,

the instructor applied EvalCourse to design queries

in a domain language to retrieve indicators about stu-

dents’ performance. These indicators were firstly ap-

plied to refine the previous assessment and secondly

to easily detect new indicators applicable to other

skills.

Results were promising, providing the manager of

the KMS with an automated process to assess diffe-

rent skills using objective indicators. Additionally,

students obtained detailed feedback, based on their

interactions in the KMS. Anyway, this part of the

process model needs further study to get a stronger

conclusion on its validity, as the use of Gescompeval

might present scalability issues if the organizational

learning have a high number of users. Nevertheless,

the computer-assisted assessment provided by Eval-

Course retrieves different indicators simply by wri-

ting a query, regardless of the number of participants.

Therefore, this is a positive evidence of its potential

when the number of users increase.

As a future work, we are enhancing the software

interface of the different tools developed so they can

be connected to other LMS different than Moodle.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was funded by the Spanish Government

under the Visaigle Project (grant TIN2017-85797-R).

REFERENCES

Abel, M.-H. and Leblanc, A. (2009). Knowledge sharing

via the e-memorae2. 0 platform. In Proceedings of

the International Conference on Intellectual Capital,

Knowledge Management & Organizational Learning,

pages 10–19.

Abu Shawar, B. and Al-Sadi, J. (2010). Learning mana-

gement systems: Are they knowledge management

tools? International Journal of Emerging Technolo-

gies in Learning (iJET), 5(1):4–10.

Ahmad, N. L., Yusuf, A. N. M., Shobri, N. D. M., and Wa-

hab, S. (2012). The relationship between time ma-

nagement and job performance in event management.

Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 65:937–

941.

Andrews, J. and Higson, H. (2008). Graduate employ-

ability, soft skills versus hard business knowledge:

A european study. Higher Education in Europe,

33(4):411–422.

Aspin, D. N. and Chapman, D. J. D. (2007). Lifelong le-

arning: Concepts and conceptions. In Philosophical

perspectives on lifelong learning, pages 19–38. Sprin-

ger.

Balderas, A., De-La-Fuente-Valentin, L., Ortega-Gomez,

M., Dodero, J. M., and Burgos, D. (2018). Learning

management systems activity records for students as-

sessment of generic skills. IEEE Access, 6:15958–

15968.

Balderas, A., Dodero, J. M., Palomo-Duarte, M., and Ruiz-

Rube, I. (2015). A domain specific language for on-

line learning competence assessments. International

Journal of Engineering Education, 31(3):851–862.

Bohlouli, M., Ansari, F., Patel, Y., Fathi, M., Loitxate Cid,

M., and Angelis, L. (2013). Towards analytical evalu-

ation of professional competences in human resource

management. In Industrial Electronics Society, IE-

CON 2013-39th Annual Conference of the IEEE, pa-

ges 8335–8340. IEEE.

Burt, C. D., Weststrate, A., Brown, C., and Champion, F.

(2010). Development of the time management envi-

ronment (time) scale. Journal of Managerial Psycho-

logy, 25(6):649–668.

Chebil, H., Girardot, J., and Courtin, C. (2012). An

ontology-based approach for sharing and analyzing le-

arning trace corpora. In Proceedings - IEEE 6th Inter-

national Conference on Semantic Computing, ICSC

2012, pages 101–108.

Crebert, G., Bates, M., Bell, B., Patrick, C., and Cragnolini,

V. (2004). Developing generic skills at university, du-

ring work placement and in employment: graduates’

perceptions. Higher Education Research & Develop-

ment, 23(2):147–165.

Assessment of Generic Skills through an Organizational Learning Process Model

299

Edwards-Schachter, M., Garc

´

ıa-Granero, A., S

´

anchez-

Barrioluengo, M., Quesada-Pineda, H., and Amara,

N. (2015). Disentangling competences: Interrelati-

onships on creativity, innovation and entrepreneurs-

hip. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 16:27–39.

EvalComix (2011). http://evalcomix.uca.es.

EvalCourse (2015). https://assembla.com/spaces/evalcourse.

Fidalgo-Blanco,

´

A., Ler

´

ıs, D., Sein-Echaluce, M. L., and

Garc

´

ıa-Pe

˜

nalvo, F. J. (2015a). Monitoring indicators

for ctmtc: comprehensive training model of the team-

work competence in engineering domain. Internati-

onal Journal of Engineering Education, 31(3):829–

838.

Fidalgo-Blanco, A., Sein-Echaluce, M. L., Garc

´

ıa-Pe

˜

nalvo,

F. J., and Conde, M. A. (2015b). Using learning ana-

lytics to improve teamwork assessment. Computers in

Human Behavior, 47(C):149–156.

Fit

´

o-Bertran,

`

A., Hern

´

andez-Lara, A. B., and L

´

opez, E. S.

(2015). The effect of competences on learning results

an educational experience with a business simulator.

Computers in Human Behavior, 51:910–914.

Gagnon, M.-P., Payne-Gagnon, J., Fortin, J.-P., Par

´

e, G.,

C

ˆ

ot

´

e, J., and Courcy, F. (2015). A learning organiza-

tion in the service of knowledge management among

nurses: A case study. International Journal of Infor-

mation Management, 35(5):636–642.

Garc

´

ıa-Morales, V. J., Jim

´

enez-Barrionuevo, M. M., and

Guti

´

errez-Guti

´

errez, L. (2012). Transformational

leadership influence on organizational performance

through organizational learning and innovation. Jour-

nal of Business Research, 65(7):1040–1050.

Gescompeval (2014). https://assembla.com/spaces/inteweb-

gescompeval.

Hennekam, S. and Bennett, D. (2017). Creative industries

work across multiple contexts: common themes and

challenges. Personnel Review, 46(1):68–85.

Huang, K.-W., Huang, J.-H., and Tzeng, G.-H. (2016). New

hybrid multiple attribute decision-making model for

improving competence sets: Enhancing a companys

core competitiveness. Sustainability, 8(2):175.

Huang, P. and Guo, Y. (2010). Research on the Relations-

hips among Knowledge Transfer, Organizational Le-

arning and Dynamic Competence. Ninth Wuhan Inter-

national Conference On E-Business, I-III:1449–1456.

Kline, E., Wallace, N., Sult, L., and Hagedon, M. (2017).

Embedding the library in the lms: Is it a good in-

vestment for your organizations information literacy

program? In Distributed Learning, pages 255–269.

Elsevier.

Liebowitz, J. and Frank, M. (2016). Knowledge manage-

ment and e-learning. CRC press.

Lombardi, M. M. (2007). Authentic learning for the 21st

century: An overview. Educause learning initiative,

1(2007):1–12.

Nawrot, I. and Doucet, A. (2014). Building engagement

for mooc students: introducing support for time mana-

gement on online learning platforms. In Proceedings

of the 23rd International Conference on World Wide

Web, pages 1077–1082. ACM.

Nita, A. M., Solomon, I. G., and Mihoreanu, L. (2016).

Building competencies and skills for leadership

through the education system. In The Internatio-

nal Scientific Conference eLearning and Software for

Education, volume 2, page 410. ” Carol I” National

Defence University.

Ozdamli, F. and Ozdal, H. (2015). Life-long learning

competence perceptions of the teachers and abilities

in using information-communication technologies.

Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 182:718–

725.

Paquette, G., Mari

˜

no, O., Rogozan, D., and L

´

eonard, M.

(2015). Competency-based personalization for mas-

sive online learning. Smart Learning Environments,

2(1):4.

Reese, C. and Hunter, D. (2016). What about the middle

man? the impact of middle level managers on orga-

nizational learning. Journal of Management, 4(1):17–

25.

Rice, W. H. (2006). Moodle: e-learning course develop-

ment: a complete guide to successful learning using

Moodle. Packt publishing Birmingham.

S

´

aiz, I., S

´

anchez, D. C., Rodr

´

ıguez,

´

A. R. L., G

´

omez, G. R.,

Ruiz, M. A. G., Noche, B. G., Serra, V. Q., Ib

´

a

˜

nez,

J. C., et al. (2010). Evalcomix en moodle: Un medio

para favorecer la participaci

´

on de los estudiantes en la

e-evaluaci

´

on. RED, Revista de Educaci

´

on a Distancia.

Special number-SPDECE.

Sch

¨

on, D. and Argyris, C. (1996). Organizational learning

ii: Theory, method and practice. Reading.

Siemens, G. (2010). What are learning analytics?

http://www.elearnspace.org/blog/2010/08/25/what-

are-learning-analytics/. Accessed: 2018-06-09.

Svetlik, I., Stavrou-Costea, E., Vakola, M., Eric Soderquist,

K., and Prastacos, G. P. (2007). Competency manage-

ment in support of organisational change. Internatio-

nal Journal of Manpower, 28(3/4):260–275.

Wang, N., Abel, M.-H., Barth

`

es, J.-P., and Negre, E. (2015).

Mining user competency from semantic trace. In IEEE

19th International Conference on Computer Suppor-

ted Cooperative Work in Design (CSCWD), pages 48–

53. IEEE.

Wang, S., Noe, R. A., and Wang, Z.-M. (2014). Motiva-

ting knowledge sharing in knowledge management sy-

stems: A quasi–field experiment. Journal of Manage-

ment, 40(4):978–1009.

WEBIST 2018 - 14th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

300