Developmental-Affordances

An Approach to Designing Child-friendly Environment

Fitri Arlinkasari

1,2

and Debra Flanders Cushing

2

1

Faculty of Psychology, YARSI University, JL. Letjen Suprapto, Cempaka Putih, Jakarta Pusat, Indonesia

2

School of Design, Queensland University of Technology, 2 George Street, Brisbane, QLD 4001, Australia

fitri.arlinkasari@hdr.qut.edu.au, debra.cushing@qut.edu.au

Keywords: Affordances, child-friendly environment, child development.

Abstract: A child-friendly environment is a place that provides children with opportunities for their activities, or from

the ecological perspective, a rich-affordances environment. However, children’s environments are often

designed by adults who may have an insufficient understanding of children’s needs, potentially causing a

disconnect between affordances provided and those actualised by children. To address this issue, we posit

developmental-affordances as an approach to designing a place for children, which integrates the theoretical

perspectives of affordances and child development. Affordance theory indicates that an environment affords

people with opportunities for action, and emphasises the relative functions of the environment according to

the perceiver’s capabilities to respond to those opportunities. However, affordances can be more effective for

designing a child-friendly place if it is informed by an understanding of the developmental stages. This

knowledge will illuminate designers with ideas for environmental features and activities that naturally attract

children as the configuration of affordances are actualised to support their development. Moreover, as child

development takes place within a specific context, designers should also note the influence of social and

physical properties of an environment that might support and thwart children’s motivation to actualise the

potential affordances.

1 INTRODUCTION

Acknowledging the global movement involving

Child Friendly Cities Initiatives (CFCI), research on

children within urban environments has increased

since the 1990s (McGlone, 2016). The movement

successfully triggered children’s participation to

evaluate as well as design their city in various ways,

include how they perceive public urban spaces. Most

prominently, important results have been generated

from the Growing Up In Cities (GUIC) and

Environmental Child-Friendliness (ECF)

frameworks, which provide us with indicators of

child-friendly environments for assessing and

designing effective places for children.

The Growing Up In Cities (GUIC) project,

initiated by UNCESCO in 1996, successfully

depicted environmental qualities of local

environments perceived by children across different

countries. Employing a participatory research design,

GUIC generated children’s perception of negative

and positive themes that define the social and

physical quality of their local environment (table 1).

The outcomes of GUIC also affirmed the findings by

Nordström in 1990 (cited in Nordström, 2010) that

the physical setting is connected to one’s social life;

thus a quality assessment of an environment must not

separate the two.

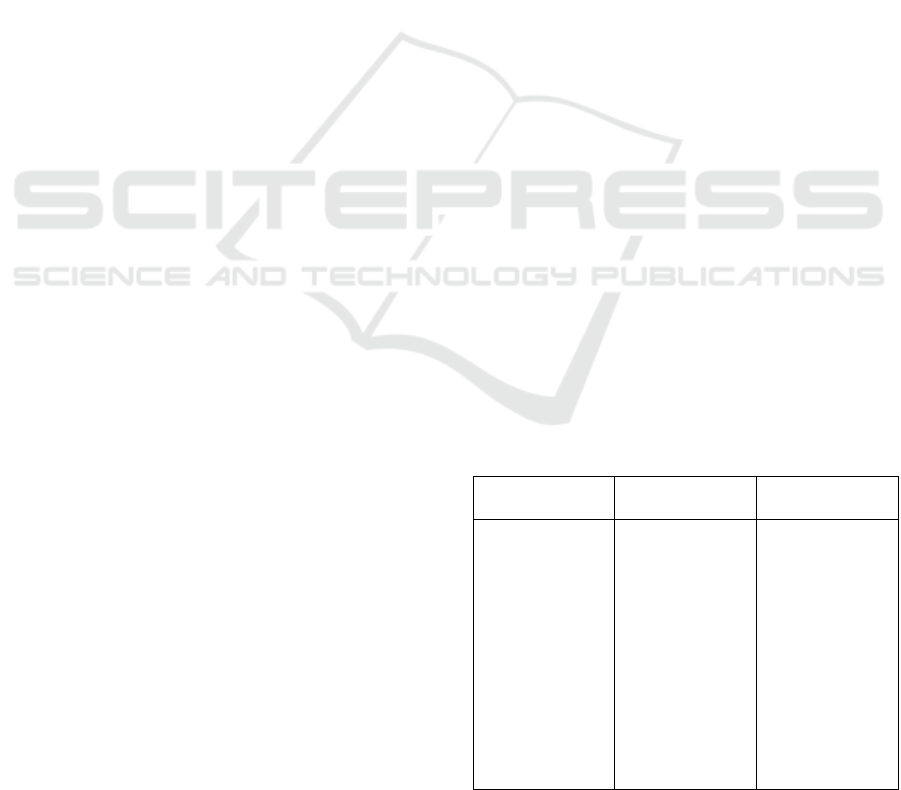

Table 1: Indicators of Children's Environmental Quality

(source: Chawla, 2002).

Social Qualities

Physical

Qualities

Positive

- Social

integration

- Freedom from

social threats

- Cohesive

community

identity

- Secure tenure

- Tradition of

community

self-help

- Green areas

- Provision of

basic services

- Variety of

activity

settings

- Freedom from

physical

dangers

- Freedom of

movement

- Peer gathering

places

94

Arlinkasari, F. and Cushing, D.

Developmental-Affordances - An Approach to Designing Child-friendly Environment.

In Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Social Sciences and Humanities (ANCOSH 2018) - Revitalization of Local Wisdom in Global and Competitive Era, pages 94-99

ISBN: 978-989-758-343-8

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

Negative

- Sense of

political

powerlessness

- Insecure

tenure

- Racial

tensions

- Fear of

harassment

and crime

- Boredom

- Social

exclusion and

stigma

- Lack of

gathering

places

- Lack of

activity

settings

- Lack of basic

services

- Heavy traffic

- Trash/litter

- Geographic

isolation

Another notable framework to identify essential

properties of child-friendly environments is

Environmental Child Friendliness (ECF) developed

by Horelli according to her research in the Finnish-

context. EFC comprises ten dimensions: housing and

dwelling; basic services; participation; safety and

security; family, kin, peers and community; urban and

environmental qualities; resources provision and

distribution poverty; ecology; sense of belonging and

continuity. The EFC also outlines “young people’s

life as a physical, psychosocial, cultural, economic

and even political entity” (Horelli, 2007, p.270). The

ten dimensions can be regarded as normative aspects

of an ideal child-friendly environment, but the form

and details of this environment are shaped by the

social-cultural context (Horelli, 2007).

From the mentioned frameworks, we can

conclude that a child-friendly environment is

indicated by opportunities that support children to

implement their needs and goals (e.g. to move freely,

to interact with others, to access services, to manage

exciting activities, and to feel safe). To create this

kind of place, a thorough understanding of children’s

needs and their socio-cultural context is fundamental

because it impacts children’s ability to access and

make use of the opportunities within a setting.

However, despite this need, children’s

environments are often designed by adults who don’t

have sufficient knowledge about the developmental

needs of children. Moreover, the process of designing

and planning spaces usually excludes children which

potentially causes a disconnection between

opportunities designed into an environment and those

actualised by children. In turn, the environment

becomes an ineffective place for children’s

development.

Yet, UNICEF (2009) stressed that healthy

development is the indicator of a child-friendly

environment. Therefore, this is a key area for further

research and consideration. Specifically, this gap

requires an approach that can lead to deeper

understanding in two areas. First, the functionality of

an environment depends in part on the perceiver’s

capabilities, which can be examined by advocating

affordances theory. Second, the utilisation of

affordances can support child’s development, which

can be better understood through human development

theories. This paper will explain how the integration

of two approaches will provide insight into a more

effective way to identify child-friendliness of a

setting as the basis for future design.

The nature of this research is a theoretical review

which collects a number of studies and project reports

of environmental design that utilise two theoretical

perspectives, namely affordances theory and

developmental psychology theories. This paper has

two aims. First, to provide an understanding of child-

friendly environment indicators. Second, to propose a

design approach that integrates the theory of

affordances and child development to meet the

indicators of the child-friendly environment.

2 AFFORDANCES THEORY

First developed in 1979 by James Gibson,

‘affordances’ denotes a transactional relationship

between perceiver and their environment, indicated

by what an environment affords the perceiver:

"The affordances of the environment are

what it offers the animal, what it provides or

furnishes, either for good or ill. The verb to

afford is found in the dictionary, but the noun

affordance is not. I have made it up. I mean by

it something that refers to both the

environment and the animal in a way that no

existing term does. It implies the

complementarity of the animal and the

environment...” (Gibson, 1979, p. 127)

In Gibson’s view, “people and animals do not

construct the world that they live in but are attuned to

the invariants of information in the environment”

(Greeno, 1994, p.337). This means properties of the

environment enable or afford the perceiver particular

opportunities to interact with that environment.

Gibson argued that environments consist of

affordances, defined as activity possibilities, as the

primary objects of human’s perception. That is why

individuals perceive the environment regarding what

behaviour it affords (i.e. a tree affords climbing, a

door affords opening, a chair affords sitting).

Furthermore, the activities are guided by how a

person detects or perceives information, often visual

cues, that specifies what the environment affords that

Developmental-Affordances - An Approach to Designing Child-friendly Environment

95

person. Gibson suggests that the environment or

object offers what it does because it is what it is. An

affordance is invariant and does not change even if

the perceiver’s needs change (Gibson, 1986).

However, an affordance exists relative to the action

capabilities of the perceiver. In Gibson’s view as

explained by Tudge, Shanahan, & Valsiner (1997),

the perceiver also must pick up “self-information” (or

assessment about his own capabilities) to respond to

the information provided by the environment:

“If perception of the environment is co-

perception of the self, then information that

specifies the environment also specifies the

self, or the actor's position in the environment.

If the environment affords some action for the

perceiver, it is in relation to the perceiver's

action capabilities.” (Tudge et al., 1997, p.

82).

3 DEVELOPMENTAL NATURE

OF AFFORDANCES

Although affordance theory does not specifically

examine human development, it is widely used by

developmental psychologists to understand the

process of learning the world through environmental

interaction. For Gibson, the world contains invariant

information that can be directly accessed by human

perception systems that adapt to retrieve this

information through direct perception, within

exploration actions (Moore and Marans, 1997).

Dynamic invariances are only revealed when humans

move actively, capturing information in their

environment. The exploration actions must be

repeated to be able to detect new invariances that exist

in the environment, so humans can achieve "real-life

perception" about the world (Richardson, 2000).

As exploration is a continuous action across the

lifespan, it leads to the development of an internal

structure that enables the new affordances which

previously have not been accessed, and in turn

support the new exploratory ability. In the course of

development, “each bit of learning affords the next -

there is a development of affordances because new

systems for information production through

integrated perception, cognition and action systems

have developed” (Richardson, 2000, p.107).

Furthermore, perception informs what action can be

done, and therefore all developmental action is based

upon the adaptive utilisation of the environment.

Briefly, Heft (1988) posits that affordances have

a developmental nature, in which one's

developmental capability determines the function of

an environment. As such, new affordances can

emerge as an implication of the rise of one's

developmental maturity and experience within the

environment. For example, older children can

perceive and actualise more affordances from streets

in their neighbourhood than young children because

of their well-developed independent mobility and

diverse experience in that place. The older children

can use streets in various ways, such as a place to

hang out with friends, to access transportation, to

observe the everyday occurrences in the city. On the

other hand, the younger children may perceive streets

as a less functional place because they spend most of

their time at home and limited independent mobility.

A number of researchers have examined the

place-affordances sought by young people according

to their developmental needs, or ‘developmental

affordances’, include play (Maier, Fadel and Battisto,

2009), and independent mobility (Kyttä, 2003;

Ramezani and Said, 2013). Previous studies also

explored affordances through what an individual feels

from doing an activity within a specific setting (Kyttä,

2003). For example, a room allows a child to have

privacy (as a feeling) which supports the activity of

emotional-regulation or as the implication of an

activity (e.g. feel relaxed when visiting a park)

(Oerter, 1998). Thus, it is possible to examine

affordances through activities and experiences.

The perceiver’s capabilities can be the starting

point for examining affordances within an

environment (Clark & Uzzell, 2006; Parke in Altman

& Wohwil, 1978). From previous explanations, we

can assume that the capabilities of the perceiver are

an implication of their maturity level. Thus,

capabilities are developmental-related attributes

which are unique within each developmental stage

(Newman and Newman, 2012). However, we still do

not thoroughly understand how environmental

interaction can support child development and what

drives the children to use specific affordances.

Therefore, we need further research to investigate the

association between voluntary activities and the

broader set of human developmental tasks.

4 DEVELOPMENTAL TASKS:

THE MOTIVATION FOR

ENVIRONMENTAL

INTERACTION

Each stage of development has its own developmental

tasks which must be fulfilled as an indication of the

ANCOSH 2018 - Annual Conference on Social Sciences and Humanities

96

readiness for the next period of life. To fulfil the

developmental tasks, children as active agents are

often encouraged to explore the physical properties of

their environment (Loebach, 2004). Van Vliet (1983)

suggests that children are naturally active in a

continuous search of new interactions with the

environment, coupled with their developing mobility.

Gradually, the child begins his exploration activities

with their current capabilities and is challenged to

increase the difficulty level of the activity in order to

positively influence the acquisition of new skills. As

Moore states, "Skills motivate interaction [with the

environment], interaction stimulates the learning of

skills" (Moore, 1986, p.15). Hence, the motivation for

environmental interaction is naturally driven by

developmental tasks and exists in all children of every

developmental stage.

Self-directed exploration of an environment also

leads children to naturally seek opportunities to

continue to challenge their actual capabilities in order

to achieve their potential capabilities. The scholars of

sociocultural paradigm (e.g. Vygotsky) believe that

these opportunities are provided in children’s

environments, and thus young people will be much

more developed if they actively interact with their

environment (Vygotsky, 1994; Mistry, Contreras and

Dutta, 2012). Their psychological system or the

ability to make meaning of experiences and take

action will develop through these environmental

interactions. By using their current stage of

development, the child will strive to achieve their

potential development with the support of the

environment (Loebach, 2004). For this reason, the

environment must provide children with an

appropriate degree of familiarity as well as

unfamiliarity, extending from the routine to

exploratory, from known to the yet-be-discovered

(Moore and Young in Altman and Wohlwill, 1978;

Matthews, 1992)

Although the urge to interact with the

environment is intrinsic, it is inevitable that

environmental properties also invite a person to

interact within that environment (Heft, 2013). From

an ecological perspective, children and the

environment simultaneously initiate the interaction.

Children's environmental interaction is influenced by

attributes of personal stimulus characteristic

(Bronfenbrenner, 1993), such as personal

characteristics, interest in world-exploration, and

directive belief about their relationship with the

world. Simultaneously, the environment has physical

and social features that initiate the transactions with

the child. The nature of the environmental properties

can either promote or thwart a child’s motivation for

environmental interaction (Tudge, Shanahan and

Valsiner, 1997).

5 DESIGNING ENVIRONMENTS

TO PROVIDE

DEVELOPMENTAL

AFFORDANCES

As discussed in previous sections, we understand that

the relationship between the perceiver and the

environment can be measured through the actions and

experiences of using the affordances which are

naturally motivated by the perceivers’ developmental

tasks. This section will explore the implications of

developmental stages on environmental design to

provide developmental affordances.

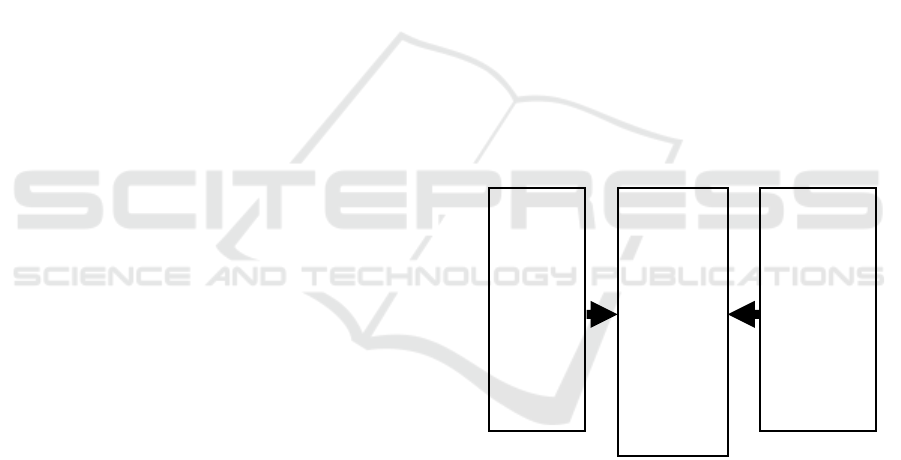

We posit three key aspects of designing an

environment that provides developmental

affordances: developmental tasks, developmental

related activities/experiences, and supportive

environmental conditions/features within which the

activities/experiences can occur. Figure 1 depicts the

relationship between the key design aspects.

Figure 1: Three key aspects of designing an environment

that supports developmental affordances (proposed by

authors).

To support our proposition, we provide an

example of developmental tasks and the supporting

environmental features for each developmental stage

during early and middle childhood (table 2).

However, an environment can be defined on a small

or large scale. Hence, this paper provides an example

of properties of a play space in the context of public

space. Public space is often assumed to be the

representation of a place that provides free access for

all ages and affords a variety of developmental

Develop

mental

Tasks

(vary

between

develop

mental

stages)

Activities/

experienc

es

motivated

by

developme

ntal tasks

which take

place

within a

context

Supportiv

e

conditions/

features of

environme

nt

(physical

and social)

Developmental-Affordances - An Approach to Designing Child-friendly Environment

97

activities (Elsley, 2004; Francis et al., 2012; Pacilli et

al., 2013).

Many approaches are discussed in the literature in

order to understand children’s behaviour related to

their development. However, in this paper, we use

developmental theory related to psychosocial by

Erikson because this approach has several advantages

(Newman and Newman, 2012; Ray, 2016). First,

psychosocial theory acknowledges the influence of

capabilities during the earlier stages on later

development. Second, this theory focuses on clear

developmental themes and the context for each

developmental stage, and the implications for failures

and successes that lead to achieving the

developmental tasks. Third, the psychosocial

approach recognises the bidirectional influence of

individuals and their environment on development,

which can be described as transactionalism as it is

adopted in affordance theory.

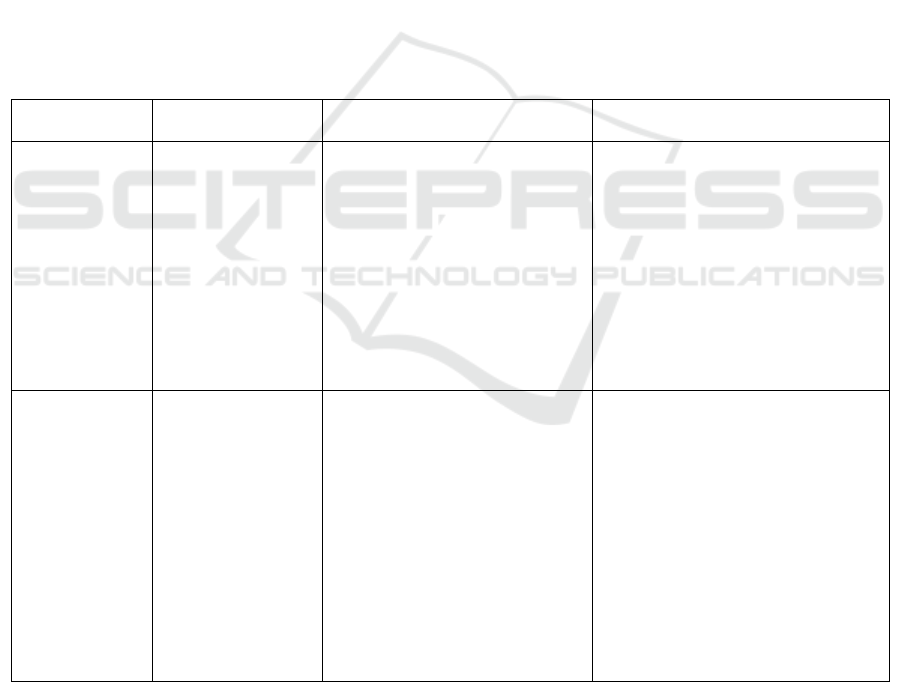

From table 2, we understand that each developmental

stage has different as well as similar preferences of

environmental features to support activities. Different

developmental stages may also have similar choices

of environmental features, but the use of them can be

flexible to accommodate different intentions

(Shackell et al., 2008). For example, a ladder within

early childhood can be used to support their gross

motor skills, while for middle childhood it can be

used to cater to their risk-taking interests by enabling

them to jump from different heights. The common use

of affordances may also appear across the

developmental stages because basically development

is not a result, but a process (Bronfenbrenner, 1993;

Richardson, 2000). Children will always be

advancing their capabilities, starting from what is

familiar to them and exploring the unfamiliar, as the

conditions needed to challenge and develop their new

skills.

Table 2: Childhood developmental stages and the supportive environmental features (adapted from Moore, 1974; Loebach,

2004; Newman and Newman, 2012; Masiulanis and Cummins, 2017).

Developmental

Stage

Developmental

Tasks

Activity/ Experiences

Supportive Environmental

Features

Early childhood

(3-6 years)

Psychosocial

crisis:

Initiative vs

guilt

- Gender

identification

- Early moral

development

- Peer play

- Climbs with confidence

- Increased speed of run

- Solitary activities

- Physical balance activity (e.g.

rides a tricycle)

- Recognising the spatial concept

(behind, under, in front of)

- Flexible elements (e.g. rocks, logs,

branches)

- Loose objects including leaves and

twigs that support diverse play

- Supporting facility for climbing

(e.g. ladders)

- More structured solitary games that

invite interaction (e.g. hide and

seek, castle with window)

- Facility for gathering and

interaction (low seat and desk) with

same age children

Middle

childhood (6-12

years)

Psychosocial

crisis:

Industry vs

inferiority

- Friendship

- Concrete

operations

- Skill learning

- Self-evaluation

- Purposive social interaction

- Team play

- Educational activity

- Risk-taking physical activity

- Restorative experience for

emotion regulation

- Adventure play properties (both

loose and fixed)

- Safe place and equipment

- Sufficient places and facilities for

group activities (e.g. soccer,

handball)

- Clear rules of place use and spatial

organisation

- Educational related tools (e.g.

reading material, counting tools)

- Adult’s support to gain new

cultural knowledge

- Restorative qualities of place, such

as privacy, relaxing atmosphere

6 CONCLUSIONS

This paper posits that developmental-affordances is a

practical approach to designing and planning child-

friendly environment. This approach will guide

designers and planners to be aware of children’s

developmental needs that drive them to engage with

specific activities within a place. Therefore, designers

and planners can create a meaningful pslace that

supports the positive outcomes of children’s

ANCOSH 2018 - Annual Conference on Social Sciences and Humanities

98

development, as it is the ultimate indicator of the

child-friendly environment.

REFERENCES

Altman, I. and Wohlwill, J. (1978) Children and the

Environment. New York: Plenum Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1993) ‘The Ecology of Cognitive

Development: Research Models and Fugitive

Findings’, in Wozniak, R. and Fischer, K. (eds)

Development in Context: Acting and Thinking in

Specific Environments. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Clark, C. and Uzzell, D. L. (2006) ‘The Socio-

Environmental affordances of adolescents’

environments’, Children and their Environments:

Learning, Using and Designing Spaces, (January

2006), pp. 176–196.

Elsley, S. (2004) ‘Children ’ s Experience of Public Space’,

Children & Society, 18, pp. 155–164. doi:

10.1002/CHI.822.

Francis, J. et al. (2012) ‘Creating sense of community: The

role of public space’, Journal of Environmental

Psychology. Elsevier Ltd, 32(4), pp. 401–409.

Gibson, J. J. (1979) The Ecological Approach to Visual

Perception, of Experimental Psychology Human

Perception and. doi: 10.2307/989638.

Greeno, J. G. (1994) ‘Gibson’s affordances.’,

Psychological Review, 101(2), pp. 336–342.

Heft, H. (1988) ‘Affordances of children’s environments :

a functional approach to environmental description’,

Children’s Environments Quarterly, 5(3), pp. 29–37.

Heft, H. (2013) ‘An ecological approach to psychology.’,

Review of General Psychology, 17(2), pp. 162–167.

Kyttä, M. (2003) Children in outdoor contexts: Affordances

and Independent Mobility in the Assessment of

Environmental Child Friendliness. Helsinki University

of Technology.

Loebach, J. (2004) Designing learning environments for

children:

Maier, J. R. A., Fadel, G. M. and Battisto, D. G. (2009) ‘An

affordance-based approach to architectural theory,

design, and practice’, Design Studies. Elsevier Ltd,

30(4), pp. 393–414.

Masiulanis, K. and Cummins, E. (2017) How to Grow a

Playspace (Development and Design). Routledge.

Matthews, M. H. (1992) Making sense of place: Children’s

understanding of large scale environments, Journal of

Rural Studies. Harvester Wheatsheaf.

McGlone, N. (2016) ‘Pop-Up kids: exploring children’s

experience of temporary public space’, Australian

Planner. Taylor & Francis, 3682(April), pp. 1–10.

Mistry, J., Contreras, M. and Dutta, R. (2012) ‘Culture and

Child Development’, in Handbook of Psychology:

developmental psychology, pp. 243–263.

Moore, G. and Marans, R. (1997) Advances in

Environment, Behavior, and Design.

Moore, R. C. (1974) ‘Patterns of Activity in Time and

Space: The Ecology of a Neighbourhood Playground’,

in Canter, D. and Lee, T. (eds) Psychology and The

Built Environment. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc.,

p. 1974.

Moore, R. C. (1986) ‘Questions of quality’, in Childhood’s

Domain (Play and Place in Child Development).

Croom Helm Ltd., pp. 1–54.

Moore, R. and Young, D. (1978) 'Children and

Neighbourhood Outdoors', in Altman, I. and Wohlwill,

J. (1978) Children and the Environment. New York:

Plenum Press.

Newman, B. M. and Newman, P. R. (2012) Development

through life.

Oerter, R. (1998) ‘Transactionalism’, in Görlitz, D.,

Harloff, H. J., Mey, G., & Valsiner, J. (ed.) Children,

cities, and psychological theories: Developing

relationships. Walter de Gruyter.

Pacilli, M. G. et al. (2013) ‘Children and the public realm:

antecedents and consequences of independent mobility

in a group of 11–13-year-old Italian children’,

Children’s Geographies, 11(4), pp. 377–393.

Parke, R. (1978) 'Children and Home Environments', in

Altman, I. and Wohlwill, J. (1978) Children and the

Environment. New York: Plenum Press.

Ramezani, S. and Said, I. (2013) ‘Children’s nomination of

friendly places in an urban neighbourhood in Shiraz,

Iran’, Children’s Geographies, 11(1), pp. 7–27.

Ray, D. C. (2016) A Therapist’s Guide to Child

Development. Routledge.

Richardson, K. (2000) Developmental Psychology: How

Nature and Nurture Interact. New J: Lawrence

Erlbaum Associates. Available at:

http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=aNh4

AgAAQBAJ&pgis=1.

Shackell, A. et al. (2008) Design for Play: A guide to

creating successful play spaces. Available at:

http://www.playengland.org.uk/media/70684/design-

for-play.pdf%0Ahttp://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/5028/.

Tudge, J., Shanahan, M. J. and Valsiner, J. (1997)

Comparisons in Human Development: Understanding

Time and Context, Cambridge studies in social and

emotional development.

Van Vliet, W. (1983) ‘Exploring the Fourth Environment:

an Examination of the Home Range of City and

Suburban Teenagers’, Environment and Behavior,

15(5), pp. 567–588.

Vygotsky, L. (1994) ‘The Problem of the Environment’, in

Van Der Veer, R. and Valsiner, J. (eds) The Vygotsky

Reader. Oxford, p. 1994.

Developmental-Affordances - An Approach to Designing Child-friendly Environment

99