The Policy of Central Borneo Provincial Government on Indigenous

Peoples' Land Rights and Its Implications to Indonesia's Positive

Laws

Ritwan Imanuel Tarigan

Postgraduate School Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia

Keywords: Central Borneo Provincial Government, Dayak Indigenous Peoples, Kedamangan, Land Rights, SKTA

(Certificate of Customary Land).

Abstract: The Central Borneo provincial government has responded positively to the protection of land occupied by

indigenous people by issuing Provincial Regulations and Governor Regulations. This policy encourages

"Kedamangan" as the central institution which is fully responsible for sustainable, efficient and

development of Dayak Customary Law, customs and positive habits in Indigenous Dayak life in Central

Borneo including land rights by issuing SKTA (Certificate of Customary Land). However, the

implementation of SKTA has not been able to accommodate by positive law of Indonesia. The purpose of

this study is to explore the extent to which the implementation of Kedamangan's policy concerning land

rights and its implications on positive law of Indonesia. Normative research is used in this study with the

statue approach concerned with the topic. Sources of data obtained from the primary data in the form of

regulations and secondary data in the form of literature relating to this study. The results show that,

substantively local government policy is very appropriate and in accordance with the constitution. However,

SKTA needs to be given legitimacy in its existence so that the element of legal certainty is fulfilled.

1 INTRODUCTION

Customary law is the original law of the Indonesian

nation that is not written in the form of the laws of

the Republic of Indonesia, which here and there

contains elements of religion. Customary law is

communal and is a reflection of the life of a nation

from time to time or it may also come from an

experience by a particular society (Lev, 1990).

One of the people who still maintain customary

law as a law that lives in the life of society and state

until today is Dayak indigenous people in Central

Borneo Province. When talking about the rights of

indigenous people, it always involves the rights of

indigenous people to the land. Land rights are a

fairly intensive and extensive issue that uses

indigenous identity and authority (Simarmata, 2015).

Indigenous stakeholder institutions still present

in Dayak indigenous communities in Central Borneo

Province are called Kedamangan. These are closely

related to the local and traditional values that grow

and develop in the Dayak tribe community.

(Abdurrahman 2002).

Kedamangan is an institution responsible for the

sustainable, efficient and development of Dayak

Customary Law, customs and positive habits in the

life of Dayak indigenous people in Central Borneo.

One of the duties and power of Kedamangan is to

issue SKTA (Certificate of Customary Land) as

written evidence confirming the ownership status of

customary land.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Indonesia is a country with heterogeneous social and

economic character. The presence of Indonesia as a

nation state is a unique phenomenon, especially

when viewed from the pluralistic side it has (see

Geertz, 2000; Benedict, 1983; Lane, 2007). In these

situations two challenges are coming soon when the

nation of Indonesia stands, that is how to create a

country that can seal plurality on one hand and on

the other hand, able to accommodate the progress to

a harmonious yet dynamic stage (Yuliyanto, 2017).

The customary law according to van

Vollenhoven in Fifik Wiryani (2009) is the rules of

632

Tarigan, R.

The Policy of Central Borneo Provincial Government on Indigenous Peoples’ Land Rights and Its Implications to Indonesia’s Positive Laws.

DOI: 10.5220/0007548406320635

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference Postgraduate School (ICPS 2018), pages 632-635

ISBN: 978-989-758-348-3

Copyright

c

2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

conduct applicable to indigenous people and foreign

easterners who on the one hand have sanctions

(hence the law) and on the other hand is not codified

(hence custom). Similar opinion is given by

Wignjodipoero (1995) asserted: "So to see whether

something custom is already customary law, then we

must see the attitude of the ruler of the legal

community concerned against the violator of the

customs rules in question. If the ruler of the offender

handed down the verdict, then the custom was

already a customary law.”

Three main types of customary law fellowship in

the study of custom law are called: (1) Genealogical

law alliance (2) Territorial legal partnership. (3)

Genealogical-territorial legal partnership which is a

merger of two legal partnership above (Wulansari,

2010). The relationship between human or human

groups with the land is very closely even can not be

separated, the relationship is eternal (Setiady, 2008).

The law will not be possible to live without

because the community consists of a collection of

individual human beings, and humans as supporters

of rights and obligations or in other words humans

are legal subjects, so society is also a legal subject.

The function of the legal community itself can

determine the legal structure, by looking at the

nature and characteristics of each customary law in

the formation of its legal norms, so that from that the

structure or content of the customary law is formed

(Rato, 2011).

Van Vollenhoven (1981) stated that the function

of the customary law community is as a frame, as

well as the function of society towards law in

general. Boedi Harsono in Husen Alting (2011)

defines customary rights (customary land rights) as a

set of authorities and obligations of a customary law

community relating to land located within its

territory as the main supporter of the livelihood and

life of the community concerned in all time.

The conception of land rights according to

customary law there are magical communal-

religious values that provide opportunities for

individual land tenure, as well as private rights,

however, ulayat rights are not the rights of

individuals. Therefore, it can be said that communal

right is communal because it is the right of the

members of the customary law community over the

land concerned. The magical-religious property

refers to the ulayat right as a common property,

believed to be something of an unseen nature and is

a relic of the ancestors and ancestors of the

indigenous peoples as the most important element of

their life and livelihoods throughout the lifetime and

throughout life (Harsono, 2005).

3 METHODOLOGY

To achieve the purpose of this study, the authors use

the type of normative research, which examines the

norms, principles, and legal doctrine, with respect to

the topic that researchers adopt. In normative

research, research on the principle of law is done

against rules that are benchmarks behave. This

research can be conducted primarily on primary and

secondary materials, as long as the materials contain

legal rules. Principle is the ideal element of the law.

Even the principle of law is the "heart" of legal

norms because the principle of law is the broadest

foundation for the birth of a rule of law (Rahardjo,

2006).

In this research, will be disclosed the extent to

which the existence of the Regulation on the Bread

and the resulting product that SKTA has harmonized

with the rules above (Soekanto and Mamudji, 2007).

To solve the problems raised and analyze the

things that become the object of research, it is

necessary the existence of legal materials. The legal

substance used in this research consists of 3 (three)

parts of legal materials, namely: Primary Legal

Material consists of legislation, official records or

treatises in legislation (Marzuki, 2009), Secondary

Legal Materials, consists of the publication of the

law, among others, consists of books, scientific

journals, scientific papers, seminar materials or other

scientific activities.

4 PROCESS AND SUBSTANCE

LEGALIZATION OF

INDIGENOUS RIGHTS OF

DAYAK COMMUNITIES ON

LAND

Customary institutions must be able to answer the

present challenge and welcome the future. Live now

how indigenous peoples and adat institutions "are

given the opportunity" to be utilized, empowered

and synergize all these potentials into development

capital (Waluyo, 2012; Sulang, 2001).

Based on Governor Regulation No. 13 Year 2009

Jo No. 4 Year 2012, to clarify the ownership of

customary land owned by private property, and the

rights to land above are as follows:

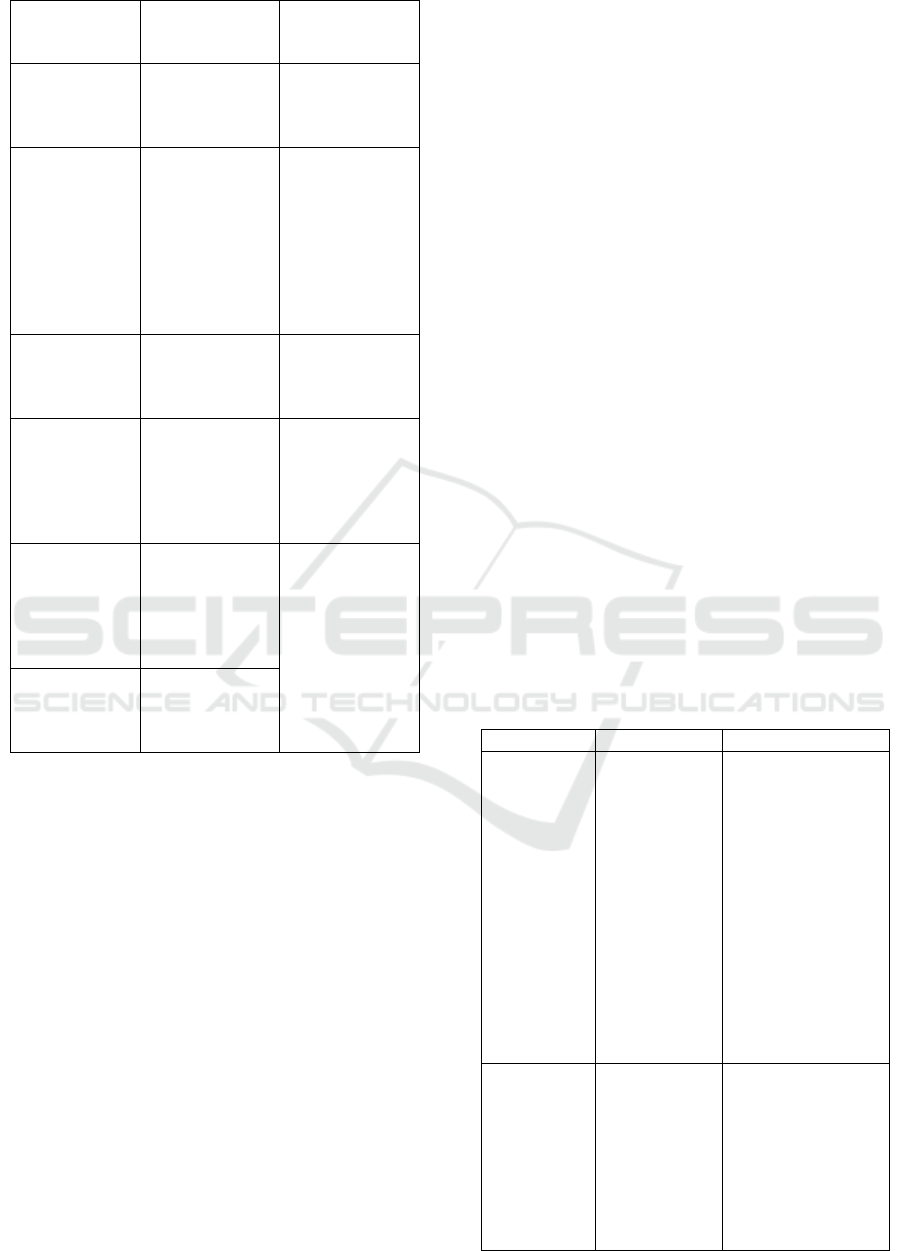

Table 1: The Difference between Land of Customs

Together, Individual Customs Land, and Customary

Rights on Land.

The Policy of Central Borneo Provincial Government on Indigenous Peoples’ Land Rights and Its Implications to Indonesia’s Positive Laws

633

LAND OF

CUSTOMS

TOGETHER

INDUVIDUAL

CUSTOMS

LAND

CUSTOMARY

RIGHTS ON

LAND

State land is

not

free (former

fields

)

State land is not

free

(former fields)

Free country

land

(virgin forest).

Ancestral

heritage land

or Parents are

still

not yet shared

The former or

own fields

from grants,

inheritance,

selling

buy / exchange.

Form: animals

game, fruits,

sap, honey,

ingredients

medicine, place

religious-

magical and

(right

gathering).

Can be forest

back or

garden.

Can be forest

back or garden.

Not the land but

only objects

above / in

in the

g

roun

d

Can be a place

stay (in the

village),

grave / shrine /

religious

ma

g

ic

Can be a place

stay (in the

village), grave,

sacred /

religious

ma

g

ical

The area and

the boundaries

are not

certain

Area and

boundary

following the

breadth and

borders

former fields

Area and

boundary

following the

breadth and

borders

former fields

If "disturbed"

the other party,

the owner

entitled to get

Transfer of

rights through

buying and

selling, etc.

Transfer of

rights through

buying and

selling, etc

4.1 Dilemma SKTA Issued by

Kedamangan in Indonesia Land

Registration System

The absence of regulation regarding the existence of

SKTA in the Government Regulation No. 24 Year

1997 concerning Land Registration becomes its own

problem. This is actually a major problem in the

registration of indigenous peoples' lands. The

available regulations have not fully recognized and

protected the existence of indigenous peoples' lands.

In such a situation, the SKTA introduced through the

Regional Regulations and Governor Regulations in

Central Borneo is an innovation to complement the

lack of national legislation in regulating the

registration of customary lands.

During this time, one of the legalization of

community land to be able to manage land

certificate to the land office is SKT (Land

Certificate), then changed into Letter of Land

Statement or briefly become Statement Letter. The

difference is that SKT is issued by Camat (District

Head), while SKTA is issued by Damang. In

addition, SKT is a statement made by the applicant

known by the Village Head and Camat. While

SKTA petitioned by the applicant for issued a letter

by Damang. So if there is a land dispute in court,

then Damang can be a witness in court.

4.2 SKTA as Partnership Transaction

Tool

Although the Government regulates that SKTA can

be used as a condition of partnership, the efficacy of

SKTA as a means of transactions that have value as

a guarantor is still not very real because SKTA can

not be used as collateral to apply for credit in banks

or other credit institutions. (Waluyo, 2012).

4.3 Doubt f Legality and Legal

Strength of SKTA

The doubts about the validity of SKTA ultimately

spread on points regarding the legal power of SKTA,

especially when compared with the SPT. Here are

the constraints on the existence of SKTA

(Simarmata, 2015):

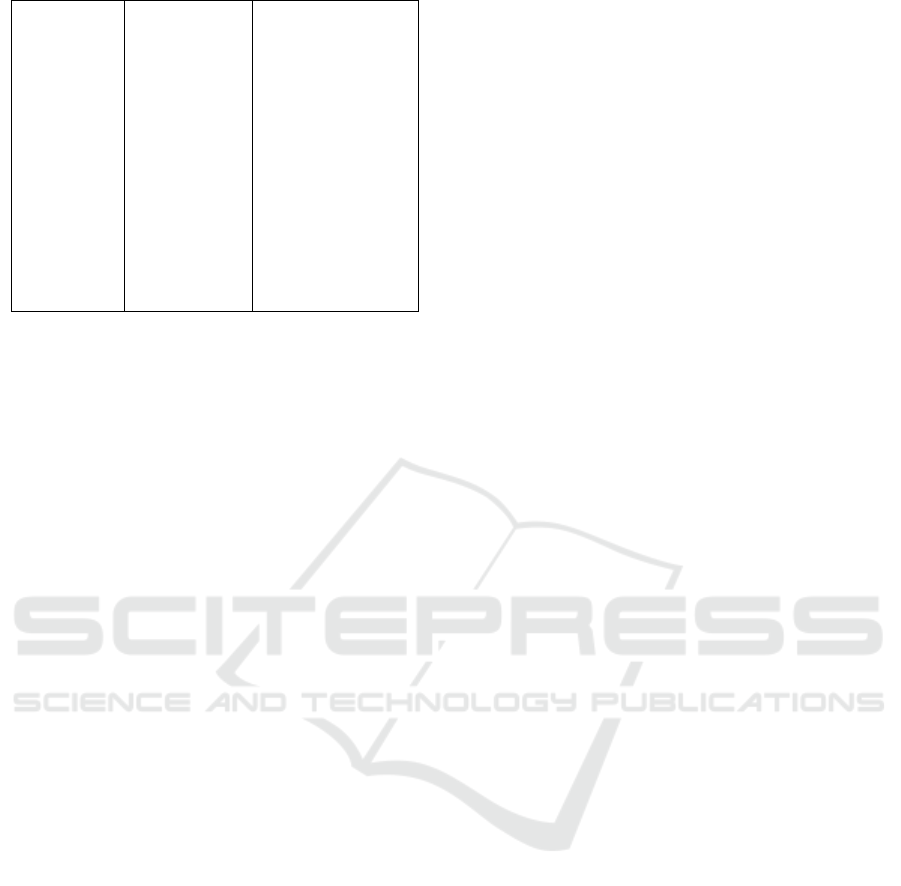

Table 2: The constraints on the existence of SKTA

(Certificate of Customary Land)

Constraints Description Explanation

Contestation

of authority

- Unclear

division

between

SPT objects

with SKTA

- Opportunity

to lose

income

The contestation

resulted in almost

no coordination

between the

damang and the

village head and the

sub-district head in

providing SKTA.

The situation

ultimately leads to

peace not being a

partner to

government but a

self-governing

government.

Doubt of

Legality and

Legal

Strength of

SKTA

- Doubt of

validity

- Doubt of

the legal

force

- Doubt

about the

value and

p

otential

- Doubts of

validity for not

being signed by

village heads

and/or sub-

district heads

- Doubt on the

power of the law

b

ecause:

(

i

)

it can

ICPS 2018 - 2nd International Conference Postgraduate School

634

for conflict not be proof of

the right to make

notarial deed and

land certificate;

(ii) can not be

used as

collateral; and

(iii) is non-

transferable

- Doubt over the

value (price) of

land due to: (i)

location; (ii) not

planted; (iii)

p

otential conflict.

From the researcher's observation of the

prevailing norm, the presence of Governor

Regulation provides legal certainty and also protects

the rights of customary land. However, if customary

land can be converted to function or move its rights,

then certainly no more customary land.

Clearly we can assume that customary land may

be transferred or dispossessed of common ownership

if there is mutual agreement through deliberation.

However, the researcher found that there is a

deficiency in the regulation that is not regulated

sanction if this joint land is converted enable in other

words sold to other parties without mutual

agreement.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Normatively it can be seen that SKTA both

technically implementation and synchronization still

experience weakness so that existence SKTA more

difficult to find its purpose. This is because there is

still no synchronization between the Government

Regulation and the Governor Regulation which

regulates the authority of the institution issuing

customary land rights certificates. The law must

always follow developments and objective

circumstances that occur in society. Government

Regulations concerning Land Registration need to

accommodate the existence of Kedamangan so that

SKTA issued can have certainty and legal strength

in its implementation. Moreover, for the sake of

legal certainty and the progress of the natural

resources of the Dayak indigenous people and to

prevent future disputes, it is very urgent to need a

clear regulation and also need to carry out ongoing

socialization to the Dayak indigenous people.

REFERENCES

Alting, Husen. 2011. Dalam Dinamika Hukum Dalam

Pengakuan dan Perindungan Hak Masyarakat Hukum

Adat Atas Tanah. Yogyakarta: LaksBang PRESSindo.

Anderson, Benedict. 1983. Imagined Communites:

Reflecitions on the Origin and Spread of nationalism.

London: Verso.

Geertz, Clifford. 2000. Available Light: Anthropological

Reflections on Philosophical Topics. New Jersey:

Princeton University Press.

Harsono, Boedi. Hukum Agraria Indonesia Sejarah

Pembentukan Undang-Undang Pokok Agraria Isi dan

Pelaksanaannya. Jakarta: Djambatan.

Lane, Max. 2007. Bangsa Yang belum Selesai: Indonesia

Sebelum dan Sesudah Soeharto. Jakarta:

ReformInstitute.

Lev, Daniel, S. 1990. Colonial Law and The Genesis of

The Indonesian State, Indonesia.

Marzuki, Peter Mahmud. 2009. Penelitian Hukum,

Cetakan Kelima. Jakarta: Kencana Prenada Media.

Rahardjo, Satjipto. 2006. Ilmu Hukum, Cetakan Keenam.

Bandung: PT Citra Aditya Bakti.

Rato, Domunikus. 2011. HukumAdat (Suatu Pengantar

Singkat Memahami Hukum Adat di Indonesia).

Yogyakarta: LaksBang PRESSindo

Setiady, Tolib. 2008. Intisari Hukum Adat Indonesia

dalam Kajian Kepustakaan. Bandung: Alfabeta.

Simarmata, Rikardo. 2015. Kedudukan Hukum dan

Peluang Pengakuan Surat Keterangan Tanah Adat.

Jakarta: Kemitraan.

Soekanto, Soerjono and Sri Mamudji. 2007. Penelitian

Hukum Normatif Suatu Tinjauan Singkat. Jakarta: PT

RajaGrafindo Persada.

Sulang, JJ Kusni. 2001. Negara Etnik, Beberapa Gagasan

Pemberdayaan Suku Dayak. Yogyakarta: Fuspad.

Vollenhoven, Van. 1981. Van Vollenhoven on Indonesian

Adat Law. Dordrect: Springer-Science and Business

Media

Waluyo, Aryo Nugroho. 2012. Petak Danum Itah

Ditentukan Oleh Surat Keterangan Tanah Adat

(SKTA). Jakarta: Epistema Institute

Wiryani, Fifik. 2009. Reformasi Hak Ulayat. Malang:

Setara Press.

Wulansari, Dewi. 2010. Hukum Adat Indonesia (Suatu

Pengantar). Bandung: Refika Aditama.

Yuliyanto. 2017. The Role of the Dayak Customary Law

in Resolving Conflict to Realize Justice and Justice. In

Jurnal Rechtvinding 6 (1). Jakarta: Media Pembinaan

Hukum Nasional.

The Policy of Central Borneo Provincial Government on Indigenous Peoples’ Land Rights and Its Implications to Indonesia’s Positive Laws

635