Mind-Body-Spiritual Care for Coronary Heart Disease Patients

A Systematic Review

Ninuk Dian Kurniawati, Nursalam

Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Airlangga, Kampus C UNAIR, Mulyorejo, Surabaya, Indonesia

Keywords: Mind-Body-Spiritual, Nursing, Care, Coronary Heart Disease, Acute Coronary Syndrome, Distress.

Abstract: Background. Coronary heart disease (CHD) patients hospitalized for acute coronary syndrome may

experience bio-psycho-spiritual distress. The objective of this study was to assess evidence of nursing care

or other interventions addressing the patient’s bio, psycho, and spiritual issues and determine the efficacy of

the existing intervention tailored to tackle the issues. Methods. A comprehensive search was carried out on

various databases i.e. PubMed (Medline), Embase, CINAHL, Scopus, Springerlink, PsycInfo, ProQuest,

EBSCOHost, Web of Science Clarivate Analytic and Science Direct. Unpublished studies were also

searched from libraries and university repositories. Results. Seventeen out of 1215 papers meeting inclusion

criteria were included in the review. The study encompassing mind, body, and spiritual nursing care was

very limited in number, most reviewed papers were not on nursing care and examined the individual

intervention. All reviewed studies reported positive results. Nevertheless, the reviewed studies were very

diverse in terms of intervention (dose, the method of delivery, length of follow up), the patients’ condition

treated, and outcome measured makes it difficult to conclude on a certain nursing care model and its

effectiveness for the CHD patients. Conclusion. Further study is necessary to develop the best nursing care

model for coronary heart disease patients and to examine its effectiveness in alleviating patients’ issues.

1 BACKGROUND

Patients with coronary heart disease (CHD) may

experience psychological distress and also physical

issues. A study conducted at three hospitals in

Surabaya, Indonesia revealed that patients with CHD

hospitalized for acute coronary syndrome

experienced psychological stress, ranging from mild

to severe in scale, as well as other issues

(Kurniawati, Nursalam & Suharto, 2017).

Psychological distress stemmed from the illness-

related issues, the hospital environment, the other

patients’ condition and separation from family or

relatives; whereas the other dominant issues were a

hemodynamic imbalance, discomfort, and pain

(Kurniawati et al., 2017). Physical stress

experienced by CHD patients included unstable

airways, oxygenation, and hemodynamic

disturbance. Psychological stress might be caused by

a critical condition, death risk, social isolation and

an alien environment (Elliot, Aitken & Chaboyer,

2007). Psychological issues when left untreated will

negatively affect CHD patients. A study involving

100 respondents confirmed the relationships

between psychological problems and biological

markers of inflammation that play a significant role

in exacerbating the CHD, namely IL-1β, IL-6, and

TNF-α (Miller, Freedland, Carney, Stetler & Banks,

2003). Another study of 82 AMI and CABG

survivors concluded that psychological distress

correlated negatively with health-related quality of

life (HRQOL), post-traumatic distress symptoms,

and mental health outcomes (Bluvstein, Moravchick

& Sheps, 2013).

Patients' spiritual need should not be neglected

by the nurse. A systematic review of 54 studies

comprising 12,327 patients concluded that many

patients want their doctor to address their spiritual

needs during the medical consultation (Best, Butow

& Olver, 2015). Similarly, a cross-sectional study in

Palestina found that providing spiritual care was

very important to 275 cardiac patients treated at a

coronary care unit (Abu-El-Noor & Abu-El-Noor,

2014). Another study found that both psychological

and spiritual care have a strong relationship with a

patient’s satisfaction (Clark, Drain & Malone, 2003).

Therefore, spiritual care is an important aspect that

cannot be overlooked.

394

Kurniawati, N. and Nursalam, .

Mind-Body-Spiritual Care for Coronary Heart Disease Patients.

DOI: 10.5220/0008325803940405

In Proceedings of the 9th International Nursing Conference (INC 2018), pages 394-405

ISBN: 978-989-758-336-0

Copyright

c

2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

Interventions that include the physical,

psychological and spiritual (mind-body-spiritual)

aspects will help the patient overcome the physical

and psychological stress optimally. Yet, to the best

of our knowledge, a systematic review regarding this

intervention is not available.

Some systematic reviews and meta-analyses

have examined the mind-based intervention and

concluded the efficacy of the intervention in

reducing stress of healthy individuals (Khoury,

Sharma, Rush & Fournier, 2015), psychological,

physical, and bio-molecular parameters of HIV

patients (Yang, Liu, Zhang, & Liu, 2015), and

patients with vascular disease (Abbott et al., 2014).

The mechanism by which the mind-based

interventions affect wellbeing has also been studied,

where a systematic review and meta-analysis of 20

studies found several factors underlying mind-based

intervention, i.e. cognitive and emotional reactivity,

mindfulness, anxiety reduction, ability in digesting

the problem, self-compassion and psychological

flexibility (Gu, Strauss, Bond & Cavanagh, 2015).

To date, there is no review that examines evidence

of mind body-spiritual nursing care for CHD

patients.This systematic review evaluates evidence

of a nursing care model addressing a patient’s issues

and determines the efficacy of the existing model

tailored to tackle the issues.

2 METHODS

The systematic review was guided by PRISMA

protocol (Preferred reporting items for systematic

review and meta-analysis) (Moher et al., 2009).

2.1 Identification of Studies

Searches of both published and unpublished studies

were conducted by the authors. The search for

published studies was done comprehensively using

several keywords: “coronary heart disease” OR

“acute coronary syndrome” OR “heart attack” OR

“hemodynamic” OR “pain”, “nurse” OR “nursing

care”, “mind*”, “body”, “spirit*”, “distress”,

“holistic”, “quality of life” OR self-efficacy, and

“well being.” The search was carried out on various

databases i.e. PubMed (Medline), Embase,

CINAHL, Scopus, Springerlink, PsycInfo, ProQuest,

EBSCOHost, Web of Science Clarivate Analytic and

Science Direct. Unpublished studies were also

searched from libraries and university repositories.

Several MeSH terms used to locate articles were

heart disease, meditation, stress, yoga,

catecholamines, hormones, hypnosis, guided

imagery, spiritual, mindfulness, body, clinical trial,

coronary artery disease, adult, and human. The

search terms were formulated using the PICO

framework, where P (population) was patients with

coronary heart disease with acute coronary

syndrome, I (intervention) was nursing intervention

or nursing model consisted of mind-body spiritual,

or mind-body or spiritual nursing, C (comparison)

was standard care or other relevant care, and O

(outcomes) was either physical, psychological, bio-

molecular or quality of life. The searches were limit

to publication in English or Bahasa Indonesia and

year of publication of 2000 up to February 2018.

2.2 Study Selection

The titles and abstracts of citations identified by

searches were examined by two reviewers

independently; disagreements about the study were

resolved by consensus among the authors.

2.2.1 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Some criteria were imposed for study selections: 1)

an experimental or observational study, 2) adult

sample, 3) patients with coronary heart disease or

acute coronary injury, 4) addressing bio-psycho-

social-spiritual issues, 5) the intervention(s) was

mind-body-spiritual or mind-body. Studies falling

under these criteria were excluded from the review:

1) reviews, 3) qualitative study, and 4) the outcome

measures did not relate to health.

2.2.2 Quality Assessment

Assessment of methodological quality of studies

meeting the inclusion criteria was conducted using

the CONSORT (consolidated standards of reporting

trials) checklist (Schulz, Altman, Moher & Group,

2010) or STROBE (strengthening the reporting of

observational studies in epidemiology) checklist

(von Elm et al., 2008). Critical appraisal was guided

by the JAMA (Journal of American Medical

Association) guides for quantitative studies (Guyatt,

Sackett & Cook, 1993, 1994). The critical appraisal

and study quality assessment were carried out by the

authors independently; and, as previously stated, any

discrepancies between the authors’ decisions were

resolved by consensus.

Mind-Body-Spiritual Care for Coronary Heart Disease Patients

395

2.2.3 Types of Interventions

Studies are considered eligible if the intervention

given was mind-body spiritual or mind-body or

spiritual care for patients.

2.2.4 Types of Outcome Measures

Outcome measures were stress reduction, spirituality

enhancement, biomolecular markers, pain reduction,

and regulation of hemodynamic parameters e.g.

blood pressure, heart rate, oxygenation. The other

outcome measures were the quality of life and

perceived self-efficacy.

2.2.5 Length of Follow-up

Studies that measure the outcome shortly after the

intervention or long after the intervention (up to 1

year) were both included in the review.

3 RESULTS

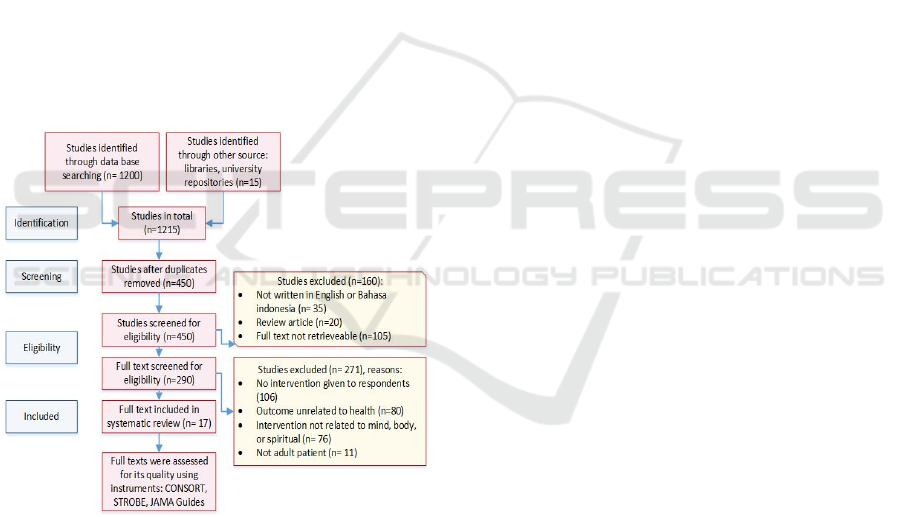

Diagram 1: Study selection based on PRISMA

statement.

As can be seen from Diagram 1, 1200 studies were

yielded from the electronic search while an

additional 15 studies were found from the manual

search. The first screening process managed to

remove 765 articles because they were identified as

duplicates. A first screening process based on

language, type of article, and availability of its full

text was able to exclude 160 articles. The remaining

290 studies were then screened for eligibility based

on some inclusion and exclusion criteria, i.e.

outcome measures, type of intervention, and sample

characteristics. Seventeen studies were included in

the review.

3.1 Study Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes articles included in the

systematic review; 4 articles were published

between 2000 and 2007 and the remaining were

published or conducted from 2010 to 2017. Studies

were conducted in diverse locations: Asia, America,

and Europe. Eleven studies were RCT and the rest of

them were not RCT experiments. Eight studies used

standard care groups, 2 articles from the same study

employed waitlist control, 2 with placebos, 1 with

self-help booklet, and 2 studies not using a control

group. Patients recruited in the studies vary slightly,

with 3 studies recruiting CHD patients peri-

operatively, 3 during acute coronary syndrome

(ACS) attack, and the remaining recruited

hospitalized CHD patients or CHD patients in the

community.

3.2 Intervention Characteristics

It was difficult to find a specific nursing intervention

or nursing care model addressing comprehensively

patients’ mind, body and spiritual needs. Table 1

summarizes the characteristics of intervention given

to the patients to address the mind, body, or spiritual

issues of the patients. There are a wide variety of

interventions given to the patients, ranging from

mindfulness exercises, yoga, spiritual mantram,

nursing care, and other interventions.

The majority of interventions were mindfulness

exercise or spiritual intervention alone, or a

combination of mind and spiritual, which were

delivered individually to the respondents; only one

intervention involved group meetings. Additionally,

most interventions were provided in healthcare

settings, only 5 interventions were given for

outpatients.Most included studies reported frequency

and dose of intervention given to respondents. The

dose ranging from 20 minutes up to 24 hours a day

with frequency ranging from once a day until

continuously during the day. The length of

intervention and follow up ranges from 3 days to 1

year. Some interventions were provided by nurses or

other healthcare professionals, the rest were done by

the respondents independently. Most of these

interventions were directed to tackle a single or

group of patients’ issues, but none of them were

tailored to overcome the mind, body, and spiritual

issues of patients comprehensively.

INC 2018 - The 9th International Nursing Conference: Nurses at The Forefront Transforming Care, Science and Research

396

Table 1: The Study and Intervention Characteristics.

No Study &

Setting

Design Sample Intervention (s) Contr

ol

Outcome

(s)

Findings

1. Bakara et al.

(2013)

Indonesia

Quasi

experim

ent

42 ACS

patients

not in

ACS

attack,

hospitaliz

ed ≥24 h,

fully

awake,

with

depression

, anxiety,

or stress;

treatment

group

(n=23, 4

D.O),

control

group

(

n=19

)

Self-emotional

freedom

technique 15 m

in duration once

only, guided by

trained

personnel

Standa

rd

care

Depressio

n, anxiety,

stress.

Significant

difference in mean

score of anxiety and

stress. No

significant

difference at

depression score

2. Bakar

(2017)

Indonesia

Quasi

experim

ent

20 ACS

patients :

Treatment

group

Control

group

Islamic nursing

care model

characterized by

maintaining

confidence,

compassion, and

com

p

etence.

Standa

rd

nursin

g care.

Psychospi

ritual

comfort

and

cortisol

level.

The nursing care

significantly

enhanced patients’

psychospiritual

comfort but it did

not attenuate the

level of cortisol.

3. Carneiro et

al. (2017)

Brazil

RCT,

double

blind

41

patients

with ACS

and other

cardiovasc

ular

disease,

allocated

randomly

into 3

groups

(@16

patients):

Spirit

passé

group

Sham

group

Placebo

group

• Spirits “passé”

group and

Sham: 10 min

sessions 3

consecutive

days,

instructed to

direct thought

at Jesus with

wishes of

healing

• Spirits group:

spirit healers

and

respondents

moved hands

longitudinally

from head to

toe for 5 m,

followed by

laying hands

over

respondents’

head and

chest.

• Sham: healer

transmitting

sincere wishes.

Placeb

o: 10

min

sessio

ns for

3

consec

utive

days

receivi

ng no

interv

ention

.

Depressio

n, anxiety,

pain

intensity,

physiologi

c

parameter

s (HR,

SpO2).

Spirit passé

significantly

effective in

reducing anxiety,

muscle tension,

improving SpO2

and well-being.

Mind-Body-Spiritual Care for Coronary Heart Disease Patients

397

4. Delui, Yari,

Khouyinezh

ad, Amini,

& Bayazi,

(2013)

Mashad,

Iran

Quasi-

experim

ent

45 CHD

patients

with

depression

(18

female, 27

male), age

40-65 y,

divided

into:

Relaxatio

n group

Meditatio

n group

Control

group

• Relaxation

group: 10

sessions of

Jacobson’s

progressive

muscle

relaxation,

@20-25 min, 3

times a day

with an

educational

CD.

• Meditation

group: 10

sessions of

mindfulness

meditation

technique,

@20-25 min, 3

times a day

with an

educational

CD.

Standa

rd

interv

ention

.

Depressio

n, systolic

blood

pressure,

diastolic

blood

pressure,

heart rate,

and

anxiety.

• Significant

reduction in

depression, BP

(systolic and

diastolic) and HR

in meditation

group.

• No significant

difference in BP,

HR, anxiety and

depression

between groups.

• A significant

reduction in

depression scores

of meditation

compared to

control group.

5. Ikedo,

Gangahar,

Quader &

Smith

(2007)

The USA

RCT 78 CHD

patients

underwent

cardiac

surgery,

divided

into:

Relaxatio

n group

(n=27)

Prayer

group

(n=24)

Control

group (n =

27

)

Given

headphones

connected to a

CD player: 1

group listened

to prayer during

the surgery, the

other listened to

relaxation

technique.

Placeb

o

Tension/a

nxiety,

depression

, anger,

No difference on all

aoutcome measures

6. Kim, Cho,

& Cho

(2017)

Busan,

Korea

Prospect

ive

cohort

34 female

patients,

mean age

52 with

microvasc

ular

angina.

• Mindfullness-

based stress

reduction for 8

consecutive

weeks,

comprises 2.5

hour weekly

practice of

mindfulness

training, body

scan, sitting

meditation, and

hatha yoga),

education (15-

30 persons of

group learning),

and 1 hour

daily practice

(meditation,

yoga, and

awareness

Baseli

ne

value

Endotheli

al

function,

Left

ventricula

r function,

reactive

brachial

flow-

mediated

dilatation.

Emotional

stress.

Mindfulness based

stress reduction

reduces all stress

parameters

(somatization,

phobic anxiety,

paranoid ideation,

and psychoticism)

except hostility,

systolic BP and

endothelial and

myocardial

function.

INC 2018 - The 9th International Nursing Conference: Nurses at The Forefront Transforming Care, Science and Research

398

training).

• Anti-anginal

medication.

7. Lukman,

Akbar, &

Ibrahim

(2012)

Indonesia

Quasi

experim

ent

42 adult

with ACS

Zikr asmaul

husna (Islamic

spiritual

mantram of the

God’s Holy

names) repeat

several times a

day.

None Anxiety Significant

reduction of anxiety

level.

8. Robert

McComb,

Tacon,

Randolph,

& Caldera,

(2004)

The USA

RCT 18 women

(mean age

60 years)

with

angina,

CHF,

hypertensi

on and

valve

disorder.

• Mindfulness

based stress

reduction

program: 2 h at

night each

week over 8 w

consisted of the

body scan,

sitting

meditation, and

hatha yoga.

• Additional

experential

learning

regarding stress

responses.

Wait

list

Stress

hormones,

sub-

maximal

stress

response

&

physical

functionin

g.

No significant main

effect or interaction

for the stress

hormones and

submaximal stress

response.

There was

significant effect

between group for

ventilation and

breathing

frequency.

9. Manchanda

et al. (2000)

India

RCT 42 men

with

angiograp

hically

proven

coronary

artery

disease

(CAD)

divided

equally to

treatment

and

control

g

rou

p

.

Yoga, control of

risk factors, diet

control and

moderate

aerobic exercise

1 year follow

up.

Standa

rd

care:

risk

factor

contro

l and

AHA’

s step

I diet

Number

of angina

attacks,

lipid

profile,

exercise

capacity,

body

weight.

Significant different

in all parameters

10. Momeni,

Omidi,

Raygan, &

Akbari

(2016)

Kashan,

Iran

RCT,

single

blind

60 cardiac

patients

8 of 2.5 h

sessions of

MBSR

comprises

structured

educational

program and

formal

meditation

(mindful body

scan, sitting

meditation,

walking

meditation, and

yoga).

Standa

rd

interv

ention

, no

psych

ologic

al

interv

ention

.

BP,

perceived

stress,

anger

measured

at pre and

post

interventi

on.

MBSR significantly

reduced anxiety,

stress, anger,

systolic BP.

Mind-Body-Spiritual Care for Coronary Heart Disease Patients

399

11. Mufarokhah

, Putra, &

Dewi (2016)

Indonesia

Quasy

experim

ent

Pre-post

test

28 ACS

patients

5 sessions of

health education

2x/w @ 30 m,

followed by

individual

counselling at

patients’ home

for 1 wee

k

.

None Coping,

medicatio

n

adherence.

Significant

difference for

coping and

medication

adherence.

12. Nyklíček,

Dijksman,

Lenders,

Fonteijn, &

Koolen

(2014)

The

Netherlands

RCT 114 adults

(94 male

and 20

female),

mean age

of 55 y.o

patient

underwent

primary

coronary

interventi

on.

• A brief

mindfulness

training: 90–

120 m weekly:

(1) psycho-

education: role

of behavior,

bodily

sensations,

emotions, and

thoughts (2)

psycho-

education: role

of mindfulness

and non-

judgmental

acceptance in

stress reduction,

(3) mindfulness

practices

(4) discussion of

one’s

experiences

while doing the

practices.

• Dail

y

p

ractice

Self-

help

bookle

t

Anxiety,

depression

, stress,

vitality,

mindfulln

ess.

No significant

effect on stress &

anxiety, depression,

and vitality.

Significant effect

on psychological

QOL, but not the

physical QOL.

13. Parswani,

Sharma, &

Iyegar

(2013)

Bangalore,

India

RCT 30 male

CHD

patients

allocated

randomly

to MBSR

and

control

group

• MBSR: 1-

1.5h/w for 8

respective

weeks of

mindfulness

meditation.

• 30 m daily

exercise of

mindfulness

meditation and

body scan

meditation,

guided by audio

cassette with

recorded

instruction.

• Instructed to

maintain health

behavior, i.e.

regular

exercise, diet.

Usual

treatm

ent:

Instru

cted to

mainta

in

health

behavi

or, i.e.

regula

r

exerci

se,

and

mainta

in

diet.

Hospital

anxiety

and

depression

, stress,

BP, BMI

measure at

pre, post-

test and 3

months

follow up.

Significant

reduction of

anxiety, depression,

BMI, systolic BP.

INC 2018 - The 9th International Nursing Conference: Nurses at The Forefront Transforming Care, Science and Research

400

14. Schneider et

al., (2012)

Fairfield,

Iowa, The

USA

RCT 201 black

CHD

patients of

both sexes

with

angiograp

hic

evidence

of

coronary

artery

stenosis.

• A 7-step

course

instruction:

1.5-2-h of

transcendenta

l meditation.

• Transcendent

al meditation:

20 m twice a

day.

• Follow up

and

maintenance

meetings up

to average of

5.4 years

Cardio

vascul

ar

health

educat

ion 20

m a

day

heart-

health

y

behavi

or.

Time to

first

mortality

BP

psychosoc

ial stress

factors;

and

lifestyle

behaviors.

Significant

reduction of

mortality risk, MI,

and stroke in CHD

patients. These

changes were

associated with

lower BP and

psychosocial stress

factors.

15. Stein et al.

(2010)

The USA

RCT 43 CABG

or CABG

plus valve

replaceme

nt

patients:

TG

(n=25)

divided

into 2

groups: 14

in the

guided

imagery

group, 11

in the

music-

only

group, CG

(n=18)

Asked to listen

to audiotapes at

least once a day,

every day, for 1

week

throughout the

preoperative

preparation and

more often if

they desired and

intraoperatively,

and again 6

months

postoperatively.

Standa

rd

care

Anxiety,

depression

, mood

disturbanc

e, anger,

fatigue,

confussio

n, and

bewilderm

ent.

No significant

difference in post

operative or 6

month follow up of

any aoutcome

measures.

16. Tacón,

McComb,

Caldera, &

Randolph

(2003)

The USA

RCT 18 heart

disease

women

(angina,

hypertensi

on, valve

disorder).

Kabat-Zinn's

mindfulness-

based stress

reduction

program: 2 h

per week plus

additional

homework

practice for

respective 8

weeks.

Wait

list

contro

l

Anxiety,

emotional

control,

coping

styles, and

health

locus of

control.

Significant

reduction of

anxiety, emotional

control and coping.

17. Warber et

al. (2011)

Michigan,

the USA

RCT

58 ACS

patients

with

depression

, recruited

from

advertise

ment and

enrolled,

41 of

which

completed

the

• Four day

workshop:

Group 1: A

spiritual

retreat

(imagery,

meditation,

drumming,

journal

writing, and

nature-based

activities).

Group 2:

Standa

rd

care

Depressio

n, spiritual

well-

being,

perceived

stress, and

hope.

Depression was not

significantly

different among

groups, hope was

significantly higher

in the intervention

group.

Mind-Body-Spiritual Care for Coronary Heart Disease Patients

401

Note: ACS: Acute coronary syndrome, AHA: American Heart Association, BP : Blood pressue, CHD:

coronary heart disease, HR: heart rate, h: hour(s), m: minute(s), MBSR: Mindfulness-based stress reduction

program, MI: myocardial infarction, w: week(s), y: year(s).

3.3 Outcomes

Most studies have proven the effectiveness of the

interventions included in the systematic review,

including psychological or biological parameters.

The positive psychological results reported in the

studies were reducing anxiety, depression, stress

(Bakara et al., 2013; Carneiro et al., 2017; Delui,

Yari, Khouyinezhad, Amini & Bayazi, 2013; Ikedo,

Gangahar, Quader & Smith, 2007; Lukman, Akbar

& Ibrahim, 2012; Momeni, Omidi, Raygan &

Akbari, 2016a; Nyklíček, Dijksman, Lenders,

Fonteijn & Koolen, 2014; Parswani, Sharma &

Iyegar, 2013; Stein et al., 2010; Tacón, McComb,

Caldera & Randolph, 2003; S L Warber et al., 2011),

increasing psycho-spiritual comfort (Bakar, 2017),

coping (Mufarokhah, Putra & Dewi, 2016), spiritual

wellbeing (Warber et al., 2011), and anger,

confusion, fatigue (Ikedo et al., 2007) and hope

(Warber et al., 2011). The reported positive

biological parameters include stress hormones

(Robert McComb, Tacon, Randolph & Caldera,

2004), hemodynamic parameters (Carneiro et al.,

2017; Delui et al., 2013; Momeni et al., 2016a;

Parswani et al., 2013), myocardial infarction attack

and cardiac revascularization (Schneider et al.,

2012) and cardiovascular function (Kim et al.,

2013).

4 DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first

systematic review of mind, body and spiritual

nursing care aimed at improving CHD patients’

mind, body, and spiritual wellness. This systematic

review followed the PRISMA statement as a

guideline in conducting the systematic review.

Seventeen articles from 16 studies were included in

the review.

This review confirmed the findings of previous

systematic reviews assessing psychological

intervention both for a healthy or sick individual of

various medical conditions that for mindfulness

alone, mind-body combination, mindfulness or

spiritual intervention alone or in combination

showed positive results for CHD patients with

various conditions (perioperative, hospitalized, at

home).

The strengths of the studies included in the

review were the clarity of reporting in terms of the

intervention provided for the respondents and the

ability for the examination of the study quality by

the authors.

Despite the aforementioned strengths of the

studies under review, there are some weaknesses of

the available studies, specifically the study designs

and the types of intervention given to the patients

under study.

Only eleven of 17 articles included in the review

employed the research design of randomized control

trial (RCT). Because the reviewed studies examine

the effectiveness of an intervention or group of

interventions, the most appropriate study design is

RCT; another study design may lead to bias because

the maturation effect cannot be examined. Not all

reviewed papers used a control group. This may lead

to outcome bias because it cannot be compared with

others.

Another issue is the rigorous approach to

conducting and analyzing findings of the studies.

Some RCT studies failed to conceal from the

respondents, or the investigators, or both, the group

treatment

course.

Lifestyle

Change

Program

(nutritional

education,

exercise, and

stress

management).

• Bi-weekly

follow up

phone calls-3

consecutive

months.

INC 2018 - The 9th International Nursing Conference: Nurses at The Forefront Transforming Care, Science and Research

402

to which the respondents had been allocated. This

may lead the investigator to tend to overestimate the

effect of the treatment. The small sample size used

in some studies (Bakar, 2017; Mufarokhah et al.,

2016; Robert-McComb et al., 2004; Tacón et al.,

2003) also poses a generalizability issue of the

studies’ findings. It was difficult to specify the

correct number for a sample size because the authors

did not report the power calculation to set the sample

size used in their studies.

Among the studies that used a comparator group,

some used a placebo, a standard treatment group, a

self-help intervention, and a waitlist. The standard

treatment group is the best choice for the type of

intervention (related to mind-body or mind-body-

spiritual) because it is ethically acceptable and

appropriate to the CHD patients. The use of a

waitlist as control group (Robert-McComb et al.,

2004; Tacón et al., 2003) may also carry the

potential for bias because the author might

overestimate the effect size, the other problem with

waitlist control is that the generalizability of the

study is limited only to the population who agreed to

wait for the intervention.

Finally, determining what is and is not a mind-

body-spiritual nursing care is impossible because

there is no study that demonstrates the

comprehensive mind, body, spiritual nursing care

found to be reviewed.

4.1 Implication for Practice

This systematic review enabled us to conclude on a

specific nursing intervention addressing mind, body,

and spiritual issues experienced by CHD patients

due to the limited supporting evidence gathered from

the review.

4.2 Implication for Research

Further study to examine a nursing care that is

tailored to address CHD patients’ mind, body, and

spiritual issues is warranted.

4.3 Limitation

The limitations of this systematic review related to

the study quality. Some reviewed studies failed to

report the randomization process, the blinding

process or others.

4.4 Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of

interest.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The study examined a comprehensive mind, body,

and spiritual nursing care for CHD patients that is

yet available. Although all reviewed papers reported

positive results, there were a wide variety of

interventions provided by various professionals,

making it difficult to conclude on a certain nursing

care model and its effectiveness for the CHD

patients.

Further study is required to develop the best

nursing care model for coronary heart disease

patients and to examine its effectiveness in

alleviating patients’ issues.

REFERENCES

Abbott, R. A., Whear, R., Rodgers, L. R., Bethel, A.,

Thompson Coon, J., Kuyken, W., … Dickens, C.

(2014). Effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress

reduction and mindfulness based cognitive therapy in

vascular disease: A systematic review and meta-

analysis of randomised controlled trials. Journal of

Psychosomatic Research, 76(5), 341–351.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.02.012

Abu-El-Noor, M. K., & Abu-El-Noor, N. I. (2014).

Importance of Spiritual Care for Cardiac Patients

Admitted to Coronary Care Units in the Gaza Strip.

Journal of Holistic Nursing, 32(2), 104–115.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010113503905

Bakar, A. (2017). Pengembangan Model Asuhan

Keperawatan (Caring) Islami Terhadap Nyaman

Psikospiritual Pada Pasien Jantung Koroner. PhD

Thesis. Universitas Airlangga.

Bakara, D. M., Ibrahim, K., Sriati, A., Bengkulu, P. K.,

Keperawatan, F., & Padjadjaran, U. (2013). Efek

Spiritual Emotional Freedom Technique terhadap

Cemas dan Depresi , Sindrom Koroner Akut Effect of

Spiritual Emotional Freedom Technique on Anxiety

and Depresseion in Patients with Acute Coronary

Syndrome. Padjajaran Nursing Journal, 1(April

2013), 48–55.

Best, M., Butow, P., & Olver, I. (2015). Do patients want

doctors to talk about spirituality? A systematic

literature review. Patient Education and Counseling,

98(11), 1320–1328.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.04.017

Bluvstein, I., Moravchick, L., & Sheps, D. (2013).

Posttraumatic Growth , Posttraumatic Stress

Mind-Body-Spiritual Care for Coronary Heart Disease Patients

403

Symptoms and Mental Health Among Coronary Heart

Disease Survivors, 164–172.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-012-9318-z

Carneiro, É. M., Barbosa, L. P., Marson, J. M., Terra, J.

A., Martins, C. J. P., Modesto, D., … Borges, M. de F.

(2017). Effectiveness of Spiritist “passe” (Spiritual

healing) for anxiety levels, depression, pain, muscle

tension, well-being, and physiological parameters in

cardiovascular inpatients: A randomized controlled

trial. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 30, 73–

78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2016.11.008

Clark, P. A., Drain, M., & Malone, M. P. (2003).

Addressing patients’ emotional and spiritual needs.

Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Safety,

29(12), 659–670. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1549-

3741(03)29078-X

Delui, M. H., Yari, M., Khouyinezhad, G., Amini, M., &

Bayazi, M. . (2013). Comparison of Cardiac

Rehabilitation Programs Combined with Relaxation

and Meditation Techniques on Reduction of

Depression and Anxiety of Cardiovascular Patients.

The Open Cardiovascular Medicine Journal, 7(1), 99–

103. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874192401307010099

Elliot, D., Aitken, L. M., & Chaboyer, W. (2007).

ACCCN’s Critical Care Nursing. Marrickville:

Elsevier Australia.

Gu, J., Strauss, C., Bond, R., & Cavanagh, K. (2015). How

do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and

mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental

health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-

analysis of mediation studies. Clinical Psychology

Review, 37, 1–12.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.006

Guyatt, G. ., Sackett, D. ., & Cook, D. . (1993). Users’

guide to the Medical Literature: II. How to Use an

Article About Therapy or Prevention: A. Are the

Results of the Study Valid. The Journal of the

American Medical Association, 270(21), 2598–2601.

Guyatt, G. ., Sackett, D. ., & Cook, D. . (1994). Users’

Guides to the Medical Literature: II. How to Use an

Article About Therapy or Prevention: B. What were

the Results and Will They Help Me in Caring for My

Patients? The Journal of the American Medical

Association, 271(1), 59–63.

Ikedo, F., Gangahar, D., Quader, M., & Smith, L. (2007).

The effects of prayer, relaxation technique during

general anesthesia on recovery outcomes following

cardiac surgery. Complementary Therapies in Clinical

Practice, 13(2), 85–94.

Khoury, B., Sharma, M., Rush, S. E., & Fournier, C.

(2015). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy

individuals: A meta-analysis. Journal of

Psychosomatic Research, 78(6), 519–528.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.03.009

Kim, B. J., Cho, I. S., & Cho, K. I. (2017). Impact of

mindfulness based stress reduction therapy on

myocardial function and endothelial dysfunction in

female patients with microvascular angina. Journal of

Cardiovascular Ultrasound, 25(4), 118–123.

https://doi.org/10.4250/jcu.2017.25.4.118

Kim, S. H., Schneider, S. M., Bevans, M., Kravitz, L.,

Mermier, C., Qualls, C., & Burge, M. R. (2013).

PTSD symptom reduction with mindfulness-based

stretching and deep breathing exercise: Randomized

controlled clinical trial of efficacy. Journal of Clinical

Endocrinology and Metabolism, 98(7), 2984–2992.

https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2012-3742

Kurniawati, N. ., Nursalam, & Suharto. (2017). Mind-

Body-Spiritual Nursing Care in Intensive Care Unit. In

Advances in Health Sciences Research: 8th

International Nursing Conference (Vol. 3, pp. 223–

228). Amsterdam: Atlantis Press.

Lukman, R., Akbar, M., & Ibrahim, K. (2012). Pengaruh

Intervensi Dzikir Asmaul Husna Terhadap Kecemasan

Klien Sindroma Koroner Akut di RSUP Dr.

Mohammad Hosein Palembang. Unpad Repository.

Retrieved from

http://lukmanrohimin.blogspot.com/2012/01/pengaruh

-intervensi-zikir-asmaul-husna.html

Manchanda, S., Narang, R., Reddy, K., Sachdeva, U.,

Prabhakaran, D Dharmanand, S., Rajani, M., &

Bijlani, R. (2000). Retardation of coronary

atherosclerosis with yoga lifestyle intervention. The

Journal of the Association of Physicians of India,

48(7), 687–694.

Miller, G. E., Freedland, K. E., Carney, R. M., Stetler, C.

A., & Banks, W. A. (2003). Cynical Hostility,

Depressive Symptoms, and the Expression of

Inflammatory Risk Markers for Coronary Heart

Disease. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 26(6), 501–

515. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026273817984

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G.,

Altman, D., Antes, G., … Tugwell, P. (2009).

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and

meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS

Medicine, 6(7). https://doi.org/ 10.1371/

journal.pmed.1000097

Momeni, J., Omidi, A., Raygan, F., & Akbari, H. (2016a).

The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on

cardiac patients’ blood pressure, perceived stress, and

anger: a single-blind randomized controlled trial.

Journal of the American Society of Hypertension,

10(10), 763–771.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jash.2016.07.007

Momeni, J., Omidi, A., Raygan, F., & Akbari, H. (2016b).

The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on

cardiac patients’ blood pressure, perceived stress, and

anger: a single-blind randomized controlled trial.

Journal of the American Society of Hypertension,

10(10), 763–771.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jash.2016.07.007

Mufarokhah, H. M., Putra, S., & Dewi, Y. (2016). Self

Management Program Meningkatkan Koping, Niat

dan Kepatuhan Berobat Pasien PJK Setelah Pemberian

Self Management Program. Jurnal NERS, 11(1), 56.

https://doi.org/10.20473/jn.V11I12016.56-62

Nyklíček, I., Dijksman, S. C., Lenders, P. J., Fonteijn, W.

A., & Koolen, J. J. (2014). A brief mindfulness based

intervention for increase in emotional well-being and

quality of life in percutaneous coronary intervention

INC 2018 - The 9th International Nursing Conference: Nurses at The Forefront Transforming Care, Science and Research

404

PCI) patients: The MindfulHeart randomized controlled

trial. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 37(1), 135–144.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-012-9475-4

Parswani, M. ., Sharma, M. ., & Iyegar, S. . (2013).

Minfulness-based stress reduction program in

coronary heart disease: a randomized control trial.

Internation Journal of Yoga, 6(2), 111–117.

Robert McComb, J. J., Tacon, A., Randolph, P., &

Caldera, Y. (2004). A Pilot Study to Examine the

Effects of a Mindfulness-Based Stress-Reduction and

Relaxation Program on Levels of Stress Hormones,

Physical Functioning, and Submaximal Exercise

Responses. The Journal of Alternative and

Complementary Medicine, 10(5), 819–827.

https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2004.10.819

Schneider, R. H., Grim, C. E., Rainforth, M. V., Kotchen,

T., Nidich, S. I., Gaylord-King, C., … Alexander, C.

N. (2012). Stress reduction in the secondary

prevention of cardiovascular disease: Randomized,

controlled trial of transcendental meditation and health

education in blacks. Circulation: Cardiovascular

Quality and Outcomes, 5(6), 750–758.

https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.96740

6

Schulz, K. F., Altman, D. G., Moher, D., & Group, C.

(2010). CONSORT 2010 statement: updated

guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised

trials. PLoS Medicine, 7(3), e1000251.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000251

Stein, T., Olivo, E., Grand, S., Namerow, P., Costa, J., &

Oz, M. (2010). A pilot study to assess the effects of a

guided imagery audiotape intervention on

psychological outcomes in patients undergoing

coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Holistic Nursing

Practice, 24(4), 213–222.

https://doi.org/10.1097/HNP.0b013e3181e90303

Tacón, A., McComb, J., Caldera, Y., & Randolph, P.

(2003). Mindfulness meditation, anxiety reduction,

and heart disease: a pilot study. Family and

Community Health, 26(1), 25–33.

von Elm, E., Altman, D. G., Egger, M., Pocock, S. J.,

Gøtzsche, P. C., & Vandenbroucke, J. P. (2008). The

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies

in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for

reporting observational studies. Journal of Clinical

Epidemiology, 61(4), 344–349.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008

Warber, S. L., Ingerman, S., Moura, V. L., Wunder, J.,

Northrop, A., Gillespie, B. W., … Rubenfire, M.

(2011). Healing the heart: a randomized pilot study of

a spiritual retreat for depression in acute coronary

syndrome patients. Explore, 7(4), 222–233.

Warber, S. L., Ingerman, S., Moura, V. L., Wunder, J.,

Northrop, A., Gillespie, B. W., … Rubenfire, M.

(2011). Healing the Heart: a Randomized Pilot Study

of a Spiritual Retreat for Depression in Acute

Coronary Syndrome Patients. Explore

, 7(4), 222–233.

Yang, Y., Liu, Y. H., Zhang, H. F., & Liu, J. Y. (2015).

Effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction and

mindfulness-based cognitive therapies on people living

with HIV: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

International Journal of Nursing Sciences, 2(3), 283–294

Mind-Body-Spiritual Care for Coronary Heart Disease Patients

405