Family Support for Better Self Care Behavior Patients with Type 2

Diabetes Mellitus

An Integrated Review

Made Mahaguna Putra, Kusnanto, Candra Panji Asmoro

Faculty of Nursing Universitas Airlangga, Kampus C Mulyorejo, Surabaya, Indonesia

Keywords : Diabetes Mellitus, Diabetes Management, Social Support, Family Support, Self Care Behavior.

Abstract : Diabetes mellitus is a serious disease in the world. Family support approach improving self-care behaviour

are important for diabetes management. The aims of this review are to identify family support for people

with diabetes mellitus from quantitative studies, and to examine and understanding self-care behaviour was

related with family support. A greater understanding of the strategies would help Indonesia nurses to

develop nursing systems for managing people with diabetes mellitus Methods: Multiple databases

(SCOPUS, MEDLINE and CINAHL) were searched for the period from 2008–2018 and

in the English article, We were reviewed the reference list of included studies and picked up additional

research. Results: This finding indicates that families are considered an important source of social support

for diabetic adults. Families positively affect the health of diabetic patients or interfere with or promote self-

care activities and alleviate the detrimental effects of stress on glycemic control. Conclusion: Self-care

behaviour can improved by family support. Family-based approach to chronic disease management is based

on family physical environment, diseases including educational, relational, and personal needs of patients

and families were emphasized.

1 BACKGROUND

Common chronic disorder of adults patients is Type

2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Over the last 5 years

the prevalence of diabetes in adults over the past 30

years has increased from 14.9% to 20.8% over the

past five years. T2DM is a disorder disease that

results in cognitive dysfunction and addiction, which

cause a significant burden on the healthcare and

social care resources. (Ishak et al., 2017).

Patients who are conducting education and

various management are essential to maintain

disruption and reduce complications. There is

significant evidence to support various interventions

to improve the outcome of diabetes. Diabetes self-

management is essential to reaching glycemic

manage and enhancing fitness effects (American

Diabetes Association, 2018). Self-management

refers back to the person’s capability to manage the

symptoms, treatment, physical and psycho

social outcomes and way of life changes inherent

to dwell with a persistent circumstance (Ishak et al.,

2017).

Effective self-management is crucial to adults

living with Type 2 diabetes. Self-management helps

maintain well-being and reduces the risk of

secondary complications, such as diabetic

retinopathy, cardiovascular diseases, peripheral

arterial disorder and amputation (Zhou et al., 2016).

Adherence to a diabetes self-management plan has

been associated with health literacy, motivation,

self-efficacy, mental health, and environmental

factors, such as social support and socio-economic

status (Ahola and Groop, 2013; Blackburn,

Swidrovich and Lemstra, 2013). A number of adults

with Type 2 diabetes report already receiving

diabetes-related support from family members

(Kovacs Burns et al., 2013; Nicolucci et al., 2016),

and many diabetes education interventions have

involved families in actively supporting adults living

with Type 2 diabetes with their self-management

plan (Hu et al., 2014; McElfish et al., 2015).

Lorig’s model for chronic disease self-

management (Lorig and Holman, 2003) and the

WHO framework for Innovative Care for Chronic

Conditions (World Health Organisation, 2002) both

identify that families and other social networks are

valuable in promoting positive health outcomes;

418

Putra, M., Kusnanto, . and Asmoro, C.

Family Support for Better Self Care Behavior Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus.

DOI: 10.5220/0008326104180427

In Proceedings of the 9th International Nursing Conference (INC 2018), pages 418-427

ISBN: 978-989-758-336-0

Copyright

c

2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

however, neither conceptual model/framework

provides a clear explanation or theoretical basis for

how families can provide effective support.

Commonly cited theoretical models in previous

family-based interventions in diabetes are the Social

Cognitive and Family Systems Theory (Vongmany

et al., 2018) models; however, both of these models

focus on parent–child interactions or educator–

student interactions rather than adult–family

interactions (Schafer, McCaul and Glasgow, 1986;

Torenholt, Schwennesen and Willaing, 2014).

Some research have proven that a more level of

social assist correlates with better diabetes self-

management. Similarly, the international Diabetes

Federation confirms that terrible social help is a

predictor of terrible adherence to prescribe therapy.

This is steady with social cognitive concept,

emphasizing that self-management occurs in a

context that consists of formal healthcare vendors,

casual social community individuals and the bodily

environment (Schiøtz et al., 2011).

Most theories of health conduct exchange

required for diabetes self care performance include a

social help element (Tillotson and Smith, 1996;

Osborn and Egede, 2010), and family participants

are considered a significant source of social help for

adults with diabetes. Own family contributors can

provide many sorts of social guide (e.g., emotional,

informational, and appraisal support), instrumental

help (i.e., observable movements that make it

possible or less difficult for a man or woman to

perform wholesome behaviors) has been most

strongly associated with adherence to self

care behaviors throughout chronic diseases

(Dimatteo, 2004). In spite of correlation evidence

helping the importance of instrumental help,

interventions not often target own family support as

a way of promoting diabetes self

care behaviours between adults. Most diabetes

intervention trials have a look at the effect of

character education on glycemic manage, without

attractive or instructing own family contributors or

accounting for member of the family aid as a method

outcome (Norris, Engelgau and Narayan, 2001).

There were few interventions for adults with

diabetes including families, but that approach was

almost inconsistent and does not affect health

outcomes. Participants in the family intervention

reported a growth in own family individual

supportive behaviours and a lower in family

members’ nonsupportive behaviours.

Enhancements in self-reported diabetes self-

care behaviours, weight, and glycemic control have

been cited, although those found adjustments had

been no longer significant (Kang et al., 2010).

Gilliland et al. (GILLILAND et al., 2002) three -

arm intervention trial was conducted in adults and

relatives of diabetes, classes not participating in

one - to - one relatives who did not receive psycho

education, and American native community for

groups of operations. The intervention groups

established small will increase in glycemic control

relative to the manipulate group. Contributors have

been not randomized to condition, and the look at

did no longer verify the interventions’ outcomes on

diabetes self-care behaviours. Therefore, further

studies are needed to effectively perform family-

mediated therapy for adults with diabetes mellitus.

(Mayberry and Osborn, 2012).

Nonetheless, many qualitative and quantitative

observational studies have reported that families can

be influential on diabetes self-management (Weiler

and Crist, 2009; Guell, 2011; hu et al., 2013;

Samuel-Hodge et al., 2013; Oftedal, 2014; Choi et

al., 2015; Mayberry, Harper and Osborn, 2016), and

some have measured an association between family

behaviours and diabetes self-management (Epple et

al., 2003; Wen, Shepherd and Parchman, 2004;

Schiøtz et al., 2011; Sankar et al., 2015; Soto et al.,

2015). An examination of this evidence is required

to provide greater insights to optimize families’

involvement in diabetes self-management (Schafer,

McCaul and Glasgow, 1986; Inzucchi et al., 2012;

Torenholt, Schwennesen and Willaing, 2014; Baig et

al., 2015).

However, these reviews mainly focus on the

family support and self-care behaviour of diabetic

patients. It is important that nurses understand

family support for increase self-care behaviour

patient with diabetes. Identification of these family

behaviours as perceived by adults living with Type 2

diabetes, and how they affect self-management is an

important first step to designing better person-

centred self-management interventions involving

family members. The aim of the present review was

to identify the family support that have an impact on

patient with diabetes self-care behavior practices. By

understanding this strategy more deeply, Indonesian

nurses can develop a nursing system for behavior

management of diabetic patients and explore

research areas that need further investigation.

2 METHODS

This review was conducted as a Integrated Literature

Review, as described by (Souza and Carvalho,

2010). This type of review is a comprehensive

Family Support for Better Self Care Behavior Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

419

methodological approach to the review and can

include experimental and non-experimental studies

to understand the phenomena analyzed. It also has a

wide range of purposes such as combining data from

theoretical and empirical literature, defining

concepts, reviewing theory and evidence, analyzing

methodological problems of specific topics.

Evidence-based practices support classification

systems according to the methodological approach

adopted based on research design such as: level 1

evidence from a result of meta-analysis of multiple

randomized controlled trials, level 2 of evidence

from individual studies such as experimental

design, for evidence from the quasi-experimental

research is level 3, descriptive (or non-experimental)

studies or adopts a qualitative approach has levels 4

for evidence, level 5 of evidence from case reports

or experience reports. According to healthcare

research and quality classification, Level 6 evidence

based on expert opinion (Burns, Rohrich and Chung,

2011).

Based on the subject matter studies were divided

into two categories. These were termed as study to

identify areas relating to family support and their

effectiveness, we selected reports on trials (e.g.

randomized clinical trials [RCT], quasi-experimental

design trials, and single group studies) and cross-

sectional studies that examined family support. We

aimed to identify the areas of strategies/

interventions for self-care behavior; we also selected

reports of qualitative research, through in-depth

interviews and descriptive studies, which explored

effective family support strategies for self-care

behavior.

Published work related to family support for

individuals with diabetes mellitus collected by

searching Scopus, Cinahl, and Medline web

database in Marh 2018. We searched abstracts and

titles of manuscripts written in English that were

published in the last 8 years (2008–2018) using key

words such as “family support”, AND “self-care

behavior”, AND diabetes management”, AND

“diabetes”, AND “nursing”. This search identified

159 reports.

Patients with type 2 or type 1 diabetes as the study

population ; they were written in English; They were

intervention studies for family support for diabetic

patients; they were descriptive studies exploring

patient preferences and evaluations of family

support strategies for self-care behaviour.

Published work was excluded if family support was

related to only glycemic control, it related to only

medication adherence, it related to only depressive

symptom, was not written in English; did not focus

on family support to self care behavior, was a scale

development study, case report with small sample

size (e.g. one or two cases;); or was a published

work review/opinion paper (n= 159). In the study

studied here, we examined the implementation of

family support for diabetic patients for self-

care behaviour and / or strategies for recognition as

effective diabetes management. We reviewed a

report focusing on self-care behaviour and other

variables on family support, participants,

instruments, survey research. These are reported

in Table 1.

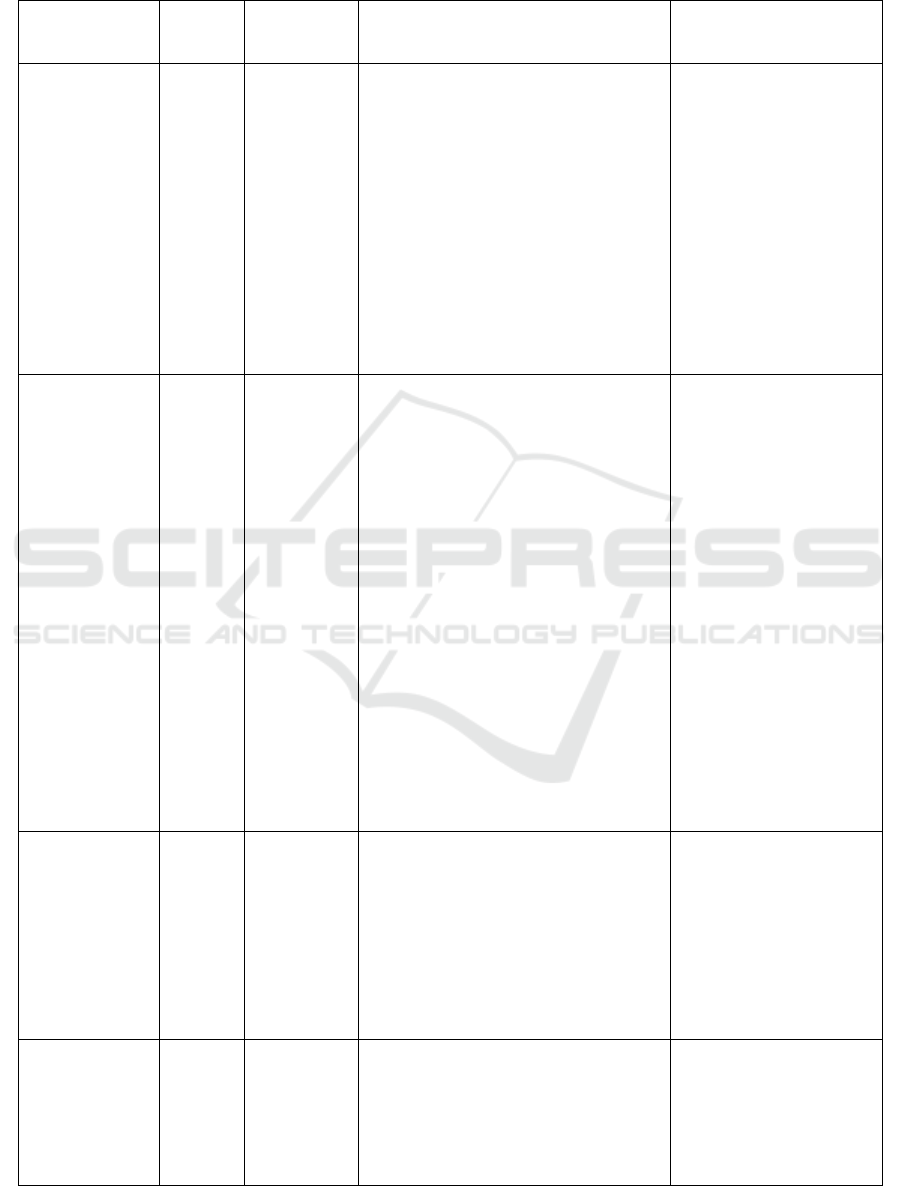

3 RESULTS

3.1 Study Characteristics

Of the 159 studies reviewed, 11 met the criteria

for this study and were selected for further analysis.

The studies were conducted in the USA (n = 6), UK

(n = 1), Saudi Arabia (n = 1), Japan (n = 1),

Denmark (n = 1), and Malaysia (n = 1). There were

some kind of studies reported, such as RCT (n = 3),

quasi-experimental (n =1 ), descriptive studies (n =

6), and mixed method (n=1).

3.2 Effectiveness of Family Support

11 studies reported the effects of their family

support on self care behavior in individuals with

diabetes mellitus. Six studies found family support

interacting statistically significantly with self-

care behaviour. 2 studies reported that family

intervention statistically significantly made better

self care behavior.

INC 2018 - The 9th International Nursing Conference: Nurses at The Forefront Transforming Care, Science and Research

420

Table 1: Family support and self care bevavior.

(Author,

published year),

countr

y

Sample Design Instrument / Intervention of the study Main findings

(Herge et al.,

2012), USA

257

family

dyads

longitudinal

RCT

Background Information :

Demographic and medical information

were obtained through a 33-item

questionnaire developed by the research

team.

Family Organization : The 9 item

organization subscale from the Family

Environment Scale

Family Self-Efficacy : Diabetes Self-

Management Scale

Disease Management : The Diabetes

Behavior Rating Scale

Frequency of Blood Glucose Checks :

To assess frequency of Blood Glucose

checks

Family organizations with

metabolic controls

provide insight into the

potential pathway for

prevention / intervention

for better management of

diabetes.

(Ishak et al.,

2017), Malaysia

143

elderly

diabetes

patients

cross-

sectional

study

Diabetic characteristic section was

filled out by the investigator based on

the clinical history and medical records

of the patient.

Chronic kidney disease or neuropathy :

glomerular filtration rate (calculated

using Modified

Diet in Renal disease (MDRD)

equation)

Self-care practices among the elderly :

Malay Elderly Diabetes Self-Care

Questionnaire (MEDSCaQ)

Self-care Activity’ questionnaire :

Malay Version of the Morisky

Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-

8)

Diabetes knowledge : The Malaysian

14-item version of the Michigan

Diabetes Knowledge Test (MDKT)

Depression : Malay version of the

geriatric Depression scale 14 (M-GDS-

14)

Family support were

significantly associated

with diabetes self-care in

elderly patients

(Watanabe et

al., 2010) Japan

112

with

type 2

diabetes

cross-

sectional

study

The questionnaire was originally

designed for evaluation of the effects of

Japanese family environment on out-

patient diet therapy and glycemic

control. Questionnaire items assessed

family diabetes enrollment, self

perception of diabetes nutritional

management, frequency and kind of

family support, and emotional response

to the support

Significant relationship

between the type of

nutritional support

(cooking or buying light

meals, advice or

encouragement) and

metabolic outcome.

(Schiøtz et al.,

2011), Denmark

2572

patients

with

Type 2

diabetes

cross-

sectional

study

Self-management behaviours :

Summary of Diabetes Self-care

Activities Scale

Patient activation : Patient Activation

Measure (PAM)

Emotional distress : ProblemAreas in

Diabetes scale (PAID-5)

Significant association

existed between poor

functional social network

and low frequency of foot

examinations (P =

0.0339)

Family Support for Better Self Care Behavior Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

421

Social network : Structural and

functional aspects

Care received by participants : Patient

Assessment of Chronic Illness Care

(PACIC) scale

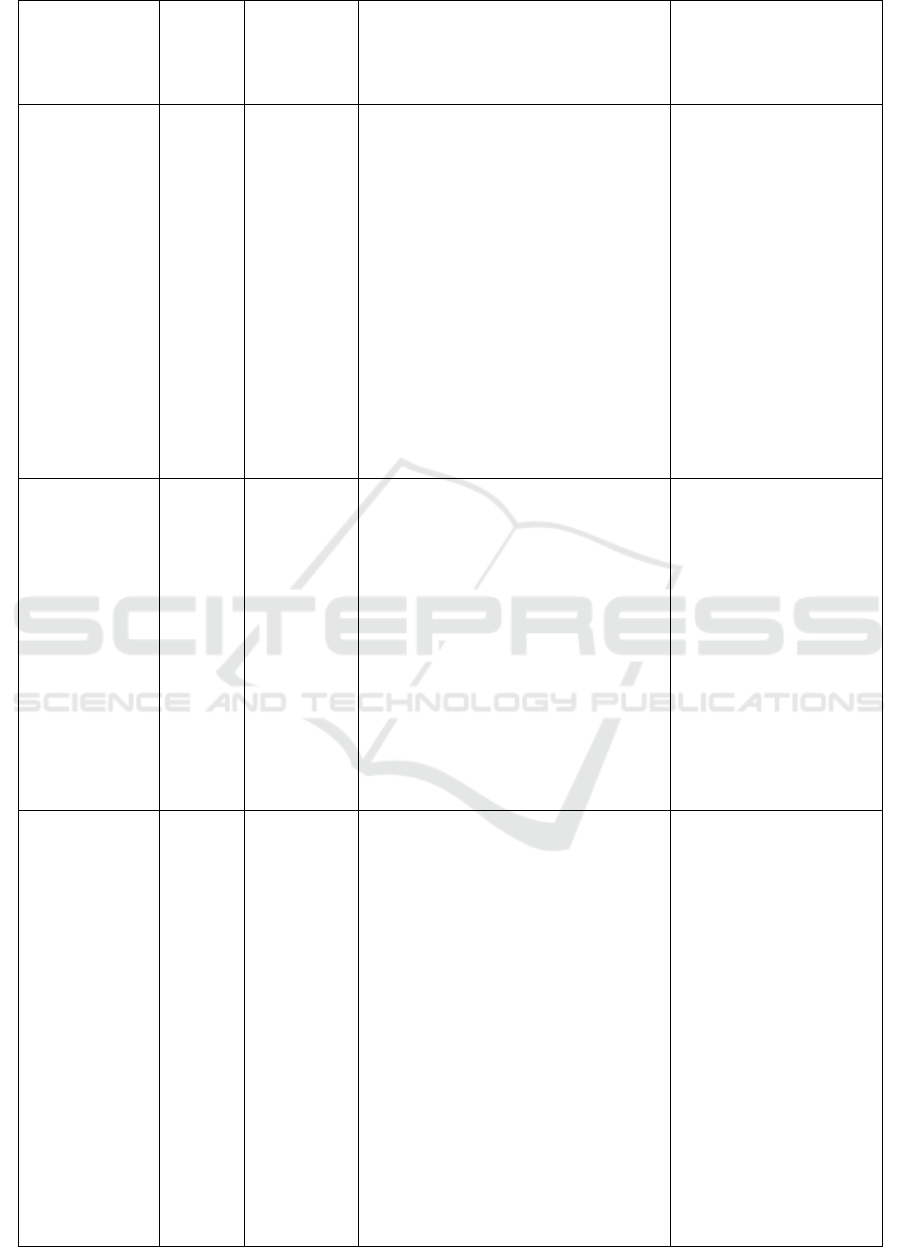

(Mayberry and

Osborn, 2012)

USA

Of those

eligible

who

consente

d to

participa

te (N =

75),

61% (n

=45)

attended

a focus

group

session

Mix method

(Qualitative

and

Quantitative

Family knowledge about diabetes

selfcare : assessed by asking

Family supportive and nonsupportive

behaviors : Diabetes Family Behavior

Checklist (DFBC)

Medication adherence : 12-item

Adherence to Refills and Medication

Scale (ARMS)

Glycemic control : the most recent

glycated hemoglobin (A1C) value in

the medical record

Perceiving family

members performed more

nonsupportive behaviors

was associated with being

less adherent to one’s

diabetes medication

regimen, and being less

adherent was associated

with worse glycemic

control. In focus groups,

participants discussed

family member support

and gave examples of

family members who

were informed about

diabetes but performed

sabotaging or

nonsu

pp

ortive behaviors.

(Murphy et al.,

2012) UK

305

adolesce

nts with

Type 1

diabetes

Randomized

trial

FACTS education programme

Biomedical measures : episodes of

severe hypoglycaemia, HbA1c was

measured every 3 months from baseline

Adolescent quality of life : Diabetes

Quality of Life Youth scale (DQOLY-

SF)

Adolescent well-being : World Health

Organization (WHO) Health Behaviour

in School Children (HBSC)

Diabetes management : Diabetes

Family Responsibility Questionnaire

(DFRQ)

Perception of their child’s diabetes

specific distress : Problem Areas in

Diabetes

(

PAID

)

scale

At 18 months there was

no significant difference

in HbA1C in either group

and no between-group

differences over time:

intervention group 75

mmol/ mol (9.0%) to 78

mmol / mol (9.3%),

control group 77 mmol/

mol (9.2%) to 80 mmol /

mol (9.5%). Adolescents

perceived no changes in

parental input at 12

months.

(Hu et al., 2014)

USA

Adult

patients

with

diabetes

(n = 36)

and

family

member

s (n =

37)

A quasi-

experimenta

l, 1 group

longitudinal

design.

Intervention : culturally tailored

diabetes educational program

Demographic forms : included family

history, health history, socioeconomic

information, and the number and

frequency of family members attending

the home visits and group meetings

Hemoglobin A1C : Bayer A1C NOW

kit

Fasting glucose and lipid profiles : A

Cholestech LDX machine (Alere, Inc.,

Waltham, MA)

Physical activity : Short International

Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)

Energy expenditure : estimated

metabolic equivalent task (MET)

Diet : Behavioral Risk Factor

Surveillance System (BRFSS)

Diabetes knowledge : Spoken

Knowledge in Low Literacy Patients

with Diabetes (SKILLD) scale.

A1C decreased by 4.9%

on average among

patients from pre-

intervention to 1 month

post-intervention. Patients

showed significant

improvements in systolic

blood pressure, diabetes

self-efficacy, diabetes

knowledge, and physical

and mental components of

health-related quality of

life.

INC 2018 - The 9th International Nursing Conference: Nurses at The Forefront Transforming Care, Science and Research

422

Family support : Diabetes Family

Support Behavior Checklist (DFBC-II)

Diabetes self-efficacy : Stanford Self-

Efficacy Scale

Diabetes self-management : Summary

of Diabetes Self-Care Activities

(SDSCA)

Health-related quality of life : Health-

related quality of life

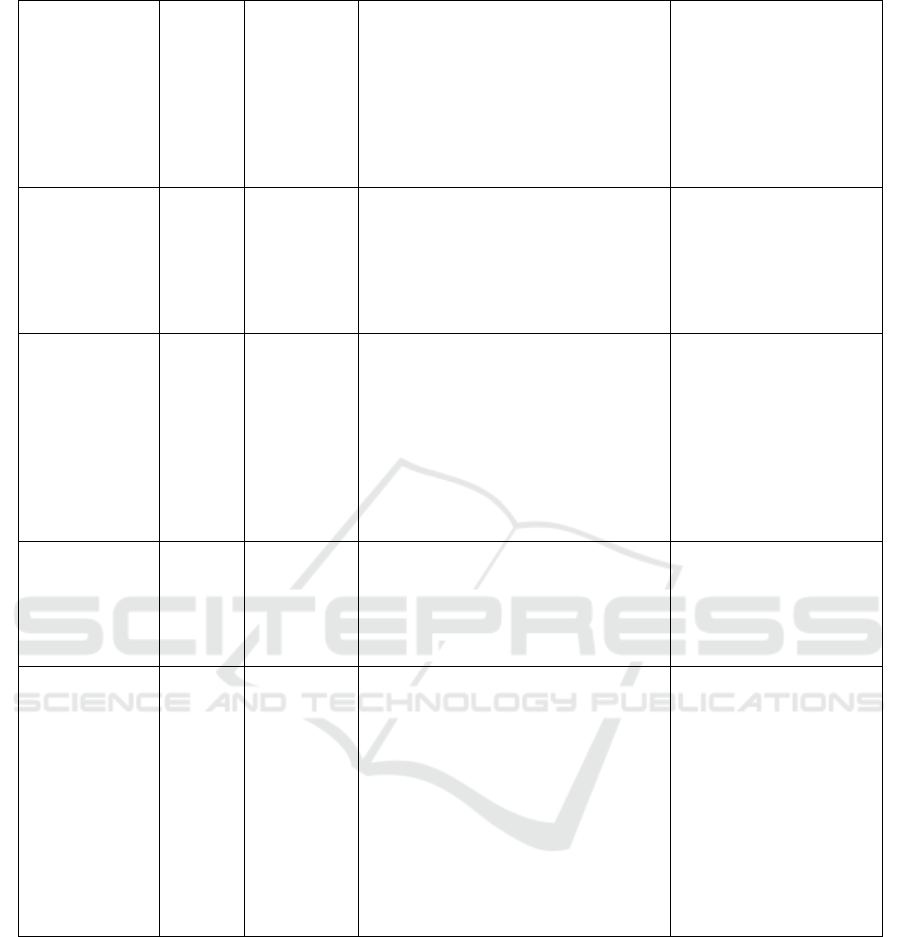

(Satterwhite and

Osborn, 2014)

USA

192

adults

with

type 2

diabetes

Cross-

sectional

study

Perceptions of family members’

supportive and obstructive behaviors :

Diabetes Family Behavior Checklist-II

(DFBC-II)

Self-care behaviors : Summary of

Diabetes Self-Care Activities (SDSCA)

Family members’

supportive and obstructive

behaviors were more

strongly related to

participants’ self-care and

explained more variation

(Aghili et al.,

2016) USA

380

adults

with

type 2

diabetes

Cross-

sectional

study

Clinical outcome variables : Total daily

calorie intake was assessed using a

single 24-hour recall.

Physical activity : International

Physical Activity Questionnaire

Diabetes self-care behaviour : self-

management profile for type 2 diabetes

A1C levels : ion exchange

chromatography (DS5 Analyzer, Drew

Scientific, Cumbria, United Kingdom)

Family and social support

was no independently

linked with A1C levels

(Badedi et al.,

2016) Saudi

Arabia

288

patients

with

T2DM

Cross-

sectional

study,

random

sample

All questionnaire created by an

interdisciplinary team from the Carver

College of Medicine, the College of

Pharmacy, and the College of Public

Health at the University of Iowa

Lower HbA1c levels

among patients who

received family support or

had close

relationship with their

p

h

y

sicians

(Song et al.,

2013) USA

83

middle-

aged

Kas

(Korean

America

ns) with

type 2

diabetes

Community

-based self-

help

intervention

program

with a

randomized

controlled

design.

Diabetes self-care activity : Summary

of Diabetes Self-Care Activities

(SDSCA).

Social support : social support

subscales of the Diabetes Care Profile

Self-efficacy : a modified form of the

Stanford Chronic Disease Self-efficacy

Scale

Unmet needs in social support was

created by summing the differences in

scores between social support needs

and the receipt of social support for

each of the 6 tasks.

Unmet needs for social

support are a significant

strong predictor of

inadequate type 2 diabetes

self-care activities, after

controlling for other

covariates.

4 DISCUSSION

This review provides insight into the diversity and

type of family behaviours that positively or

negatively affect diabetes self-management, for the

first time the "uncertain" family behavioral optimum

that diabetic patients can recognize as diabetic

patients Diabetes management barriers or promoters.

For example, some people welcomed this

information with reference to periodic reminders,

but others recognized this as "troubles",

strengthened non-compliance, and strengthened. If

this is correct, this interpretation is a window of

opportunity for intervention aimed at assisting

diabetes adults to recognize behaviors that are not

obvious and to help them become a facilitator, not a

self-management barrier.

We were reviewed published research which

examined the relationship between social support of

diabetes adults and self-care behaviour. Evidence of

beneficial effects of social support for self-care

behavior (multidimensional evaluation of family

support and social support) is emerging. Limited

evidence of being married with a partner was

Family Support for Better Self Care Behavior Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

423

associated with worsening self-care behaviour. The

majority of statistical associations in the review were

significant. The main findings are the importance of

families in the management of type 2 diabetes. We

discovered that we believe that cooperating as a

couple with a common goal is supportive. It has

been shown that lack of support for patient self-care

behavior may interfere with patient efforts to

implement the necessary behavioral changes.

Much of a patient’s diabetes management takes

place within his/her family and social environment

(World Health Organisation, 2002). Addressing the

family environment for adults on diabetes is

important since this is the context in which the

majority of disease management occurs. Families as

two or more people who are somehow biologically,

legally and emotionally related defines family as two

or more people legally or emotionally related (Baig

et al., 2015). Thus, families may include nuclear,

extended, and relatives network members.

Family members can actively support and care

for patients with diabetes (CA et al., 2003). Most

individuals live within a household that has a great

influence on diabetes-management behaviors. A

survey of over 5000 adults with diabetes highlighted

the importance of improving well-being and self-

management by families, friends, colleagues

(Kovacs Burns et al., 2013). Family members are

often asked to share in the responsibility of disease

management. They can provide a variety of support

such as instrumental assistance to help patients to

appointment and help inject insulin, in overcoming

the illness of patients were assisted with social and

emotional support (Fisher et al., 1998; Wagner et

al., 2001). Through family communication and

attitudes, patients often have psychological well-

being, decisions to comply with medical

recommendations, and the ability to initiate and

maintain changes in diet and exercise often. Among

middle-aged and elderly people with type 2 diabetes,

long-term follow-up research reveals that

autonomous improvement of health status is related

to social support (Nicklett et al., 2013). Family unity

and family functions have also been found to be

positively correlated with patient self-care behaviour

and improvement in glycemic control (Griffith, Field

and Lustman, 1990; Walker et al., 2015).

Offering diabetes education only to patients with

type 2 diabetes may limit the effect on patients as

families may play a major role in disease

management. A family-based approach to chronic

disease management emphasizes the situation in

which the disease occurs, including family physical

environments, educational, relationship between

personal needs patient and family (Fisher et al.,

1998; Armour et al., 2005). Including family

intervention in educational intervention, support for

diabetic patients, development of healthy

family behaviours, self-management of diabetes (Hu

et al., 2014).

The self-management intervention of diabetes

can focus on family communication skills and may

need to teach positive ways to influence the patient's

health behaviour. Families may suffer from the

beloved person's diabetes (Fisher et al., 2002;

Gleeson-Kreig, Bernal and Woolley, 2002; Rosland

et al., 2010; Baig et al., 2015) knowledge on

diabetes is limited or I do not know how to support

loved ones (Carter-Edwards et al., 2001; Fisher et

al., 2002; Rosland et al., 2010; Keogh et al., 2011;

hu

et al., 2013). Family may also have

misunderstandings that they believe they know the

details of diabetes than they actually report, or They

do not understand the needs of family members in

diabetes management (Carter-Edwards et al., 2001;

White et al., 2009). The disease knowledge, the

strategy to change the family routine, the best way to

deal with the emotional side of the illness is part of

the self-management aspect of diabetes that the

family needs (Orvik, Ribu and Johansen, 2010).

Teaching families about the necessity of treating

diabetes will find out why these changes are

necessary, how to make these changes in the best

way, where to find additional information such as

healthy recipes and exercise routines By explaining

what to do. Effective family management can also

decrease the stress that families may experience

when dealing with a changing lifestyle or disease

progression (Baig et al., 2016). It is important to

provide family members with information about the

illness and possible treatment options, validate their

experiences as providers of support, helps to plan the

future and teaches some stress management skills

(Martire et al., 2010).

Carefully designed research is needed to evaluate

the benefits of diabetes self-management

intervention in patients and families (Martire, 2005).

How families manage chronic disease affects not

only the patient’s health, but the health of others in

the family as well (Fisher et al., 2002). Assessing

family members’ knowledge in diabetes self-care

and perceived ability to support their loved one with

diabetes may be important end points for diabetes

self-care interventions. Families may also be more

directly advantageous by relieving psychological

distress of beloved diabetes and by participating in a

health education program to improve their own

health behaviour (Trief et al., 2001; Fisher et al.,

INC 2018 - The 9th International Nursing Conference: Nurses at The Forefront Transforming Care, Science and Research

424

2002; Sorkin et al., 2013). In addition, families with

high risk of diabetes may reduce the possibility of

developing diabetes due to improvement in lifestyle

habits and weight loss. In the review of randomized

controlled trials of chronic disease interventions, that

the benefits of families were scarcely evaluated

(Martire, 2005).

The knowledge of family support is essential for

diabetes management. This does not mean, that a

strong family relationship enhances family and

public compliance. The family dynamics described

in this review will not be restricted to diabetic

families, except for situations which are probably

caused by hypoglycemia. Therefore, our results are

potentially related to other chronically ill families

whose adherence to a particular lifestyle is

recommended. This is a potentially important

problem for future research.

5 CONCLUSIONS

We identified family support can improving self

care behavior. A family-based approach to chronic

disease management emphasizes the situation in

which the disease occurs, including family physical

environments, educational, relational, and patients

and families needs.

REFERENCES

. Aghili, R. et al. (2016) ‘Type 2 Diabetes : Model of

Factors Associated with Glycemic Control’, Canadian

Journal of Diabetes. Elsevier Inc., 40(5), pp. 424–430.

doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2016.02.014.

Ahola, A. J. and Groop, P. H. (2013) ‘Barriers to self-

management of diabetes.’, Diabetic medicine, 30(4),

pp. 413–420. doi: 10.1111/dme.12105.

American Diabetes Association (2018) ‘Introduction:

Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2018’,

Diabetes Care, 41(Supplement 1), pp. S1–S2. doi:

10.2337/dc18-Sint01.

American Diabetes Association (ADA) (2017) ‘Standard

of medical care in diabetes - 2017’, Diabetes Care, 40

(sup 1)(January), pp. s4–s128. doi: 10.2337/dc17-

S003.

Armour, T. A. et al. (2005) ‘The effectiveness of family

interventions in people with diabetes mellitus: a

systematic review.’, Diabetic Medicine, 22(10), pp.

1295–1305.

Badedi, M. et al. (2016) ‘Factors Associated with Long-

Term Control of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus’, Journal of

Diabetes Research, 2016.

Baig, A. A. et al. (2015) ‘Family interventions to improve

diabetes outcomes for adults’, Annals of the New York

Academy of Sciences, 1353(1), pp. 89–112. doi:

10.1111/nyas.12844.

Baig, A. A. et al. (2016) ‘Family interventions to improve

diabetes outcomes for adults’, Ann N Y Acad Sci,

1353(1), pp. 89–112. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12844.Family.

Blackburn, D. F., Swidrovich, J. and Lemstra, M. (2013)

‘Non-adherence in type 2 diabetes: Practical

considerations for interpreting the literature’, Patient

Preference and Adherence, 7, pp. 183–189. doi:

10.2147/PPA.S30613.

Burns, P. B., Rohrich, R. J. and Chung, K. C. (2011) ‘The

levels of evidence and their role in evidence-based

medicine’, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery,

128(1), pp. 305–310. doi:

10.1097/PRS.0b013e318219c171.

CA, C. et al. (2003) ‘Family predictors of disease

management over one year in Latino and European

American patients with type 2 diabetes.’, Family

Process, 42(3), p. 375–390 16p. Available at:

http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&d

b=c8h&AN=106692512&%5Cnlang=ja&site=eho

st-live.

Carter-Edwards, L. et al. (2001) ‘They Care But Don’t

Understand": Family Support of African American

Women With Type 2 Diabetes’, Diabetes Care, 24(3),

pp. 1144–1150.

Choi, S. E. et al. (2015) ‘Spousal Support in Diabetes

Self-Management Among Korean Immigrant Older

Adults’, Research in Gerontological Nursing, 8(2), pp.

94–104. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20141120-01.

Dimatteo, M. R. (2004) ‘Social Support and Patient

Adherence to Medical Treatment : A Meta-Analysis’,

Health Psychology, 23(2), pp. 207–218. doi:

10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.207.

Epple, C. et al. (2003) ‘The role of active family

nutritional support in Navajos’ type 2 diabetes

metabolic control’, Diabetes Care, 26(10), pp. 2829–

2834. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.10.2829.

Fisher, L. et al. (1998) ‘The family and type 2 diabetes: a

framework for intervention.’, The Diabetes educator,

24(5), pp. 599–607. doi:

10.1177/014572179802400504.

Fisher, L. et al. (2002) ‘Depression and anxiety among

partners of European-American and Latino patients

with type 2 diabetes’, Diabetes Care, 25(9), pp. 1564–

1570. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.9.1564.

GILLILAND, S. S. et al. (2002) ‘Strong in Body and

Spirit’, Diabetes Care, 25(1).

Gleeson-Kreig, J., Bernal, H. and Woolley, S. (2002) ‘The

role of social support in the self-management of

diabetes mellitus among a Hispanic population.’,

Public health nursing, 19(3), pp. 215–222. doi:

10.1046/j.0737-1209.2002.19310.x.

Griffith, L. S., Field, B. J. and Lustman, P. J. (1990) ‘Life

Stress and Social Support in Diabetes: Association

with Glycemic Control’, The International Journal of

Psychiatry in Medicine, 20(4), pp. 365–372. doi:

10.2190/APH4-YMBG-NVRL-VLWD.

Guell, C. (2011) ‘Diabetes management as a Turkish

family affair: Chronic illness as a social experience’,

Family Support for Better Self Care Behavior Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

425

Annals of Human Biology, 38(4), pp. 438–444. doi:

10.3109/03014460.2011.579577.

Herge, W. M. et al. (2012) ‘Family and Youth Factors

Associated With Health Beliefs and Health Outcomes

in Youth With Type 1 Diabetes’, Journal of Pediatric

Psychology, 37(9), pp. 980–989.

hu, J. et al. (2013) ‘Perceptions of Barriers in Managing

Diabetes: Perspectives of Hispanic Immigrant Patients

and Family Members’, The Diabetes Educator, 39(4),

pp. 494–503. doi: 10.1177/0145721713486200.

Hu, J. et al. (2014) ‘A Family-Based Diabetes Intervention

for Hispanic Adults and Their Family’, The Diabetes

Educator, 40(1). doi: 10.1177/0145721713512682.

Inzucchi, S. E. et al. (2012) ‘Management of

hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: A patient-centered

approach’, Diabetes Care, 35(6), pp. 1364–1379. doi:

10.2337/dc12-0413.

Ishak, N. H. et al. (2017) ‘Diabetes self-care and its

associated factors among elderly diabetes in primary

care’, Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences.

Elsevier Ltd, 12(6), pp. 504–511. doi:

10.1016/j.jtumed.2017.03.008.

Kang, C. et al. (2010) ‘Comparison of family partnership

intervention care vs . conventional care in adult

patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes in a

community hospital : A randomized controlled trial’,

International Journal of Nursing Studies. Elsevier Ltd,

47(11), pp. 1363–1373. doi:

10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.03.009.

Keogh, K. M. et al. (2011) ‘Psychological family

intervention for poorly controlled type 2 diabetes.’,

The American journal of managed care, 17(2), pp.

105–113.

Kovacs Burns, K. et al. (2013) ‘Diabetes Attitudes,

Wishes and Needs second study (DAWN2TM): Cross-

national benchmarking indicators for family members

living with people with diabetes’, Diabetic Medicine,

30(7), pp. 778–788. doi: 10.1111/dme.12239.

Lorig, K. R. and Holman, H. R. (2003) ‘Self-management

education: History, definition, outcomes, and

mechanisms’, Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 26(1),

pp. 1–7. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_01.

Martire, L. M. (2005) ‘The“ Relative” Efficacy of

Involving Family in Psychosocial Interventions for

Chronic Illness: Are There Added Benefits to Patients

and Family Members?’, Families systems health,

23(3), p. 312. doi: 10.1037/1091-7527.23.3.312.

Martire, L. M. et al. (2010) ‘Review and meta-analysis of

couple-oriented interventions for chronic illness’,

Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 40(3), pp. 325–342.

doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9216-2.

Mayberry, L. S., Harper, K. J. and Osborn, C. Y. (2016)

‘Family behaviors and type 2 diabetes: What to target

and how to address in interventions for adults with low

socioeconomic status’, Chronic Illness, 12(3), pp.

199–215. doi: 10.1177/1742395316644303.

Mayberry, L. S. and Osborn, C. Y. (2012) ‘Family

Support, Medication Adherence, and Glycemic

Control Among Adults With Type 2 Diabetes’,

Diabetes Care, 35(6), pp. 1239–1245. doi:

10.2337/dc11-2103.

McElfish, P. A. et al. (2015) ‘Family Model of Diabetes

Education With a Pacific Islander Community’, The

Diabetes Educator, 41(6), pp. 706–715. doi:

10.1177/0145721715606806.

Murphy, H. R. et al. (2012) ‘Education and Psychological

Issues Randomized trial of a diabetes self-

management education and family teamwork

intervention in adolescents with Type 1 diabetes’,

Diabetic Medicine, 29(8), pp. 249–254. doi:

10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03683.x.

Nicklett, E. J. et al. (2013) ‘Direct social support and long-

term health among middle-aged and older adults with

type 2 diabetes mellitus’, Journals of Gerontology,

Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences,

68(6), pp. 933–43. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt100.

Nicolucci, A. et al. (2016) ‘Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes

and Needs Second Study (DAWN2TM):

Understanding Diabetes-Related Psychosocial

Outcomes for Canadians with Diabetes’, Canadian

Journal of Diabetes, 40(3), pp. 234–241. doi:

10.1016/j.jcjd.2015.11.002.

Norris, S. L., Engelgau, M. M. and Narayan, K. M. V.

(2001) ‘Effectiveness of Self-Management Training in

Type 2 Diabetes A systematic review of randomized

controlled trials’, Diabetes Care, 24(3).

Oftedal, B. (2014) ‘Perceived support from family and

friends among adults with type 2 diabetes’, European

Diabetes Nursing July, 11(2), pp. 43–48. doi:

10.1002/edn.247.

Orvik, E., Ribu, L. and Johansen, O. E. (2010) ‘Spouses’

educational needs and perceptions of health in partners

with type 2 diabetes’, European Diabetes Nursing,

7(2), pp. 63–69. doi: 10.1002/edn.159.

Osborn, C. Y. and Egede, L. E. (2010) ‘Validation of an

Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills model of

diabetes self-care (IMB-DSC)’, Patient Education and

Counseling, 79(1), pp. 49–54. doi:

10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.016.

Rosland, A. M. et al. (2010) ‘Family influences on self-

management among functionally independent adults

with diabetes or heart failure: Do family members

hinder as much as they help?’, Chronic Illness, 6(1),

pp. 22–33. doi: 10.1177/1742395309354608.

Samuel-Hodge, C. D. et al. (2013) ‘Family diabetes

matters: A view from the other side’, Journal of

General Internal Medicine, 28(3), pp. 428–435. doi:

10.1007/s11606-012-2230-2.

Sankar, U. V. et al.

(2015) ‘The adherence to medications

in diabetic patients in rural Kerala, India’, Asia-Pacific

Journal of Public Health, 27(2), p. NP513-NP523.

doi: 10.1177/1010539513475651.

Satterwhite, L. and Osborn, C. Y. (2014) ‘Family

involvement is helpful and harmful to patients ’ self-

care and glycemic control Suppor tive Behaviors

Obstru ctive Behaviors’, Patient Education and

Counseling. Elsevier Ireland Ltd, 97(3), pp. 418–425.

doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.09.011.

Schafer, L. C., McCaul, K. D. and Glasgow, R. E. (1986)

‘Supportive and nonsupportive family behaviors:

INC 2018 - The 9th International Nursing Conference: Nurses at The Forefront Transforming Care, Science and Research

426

Relationships to adherence and metabolic control in

persons with type I diabetes’, Diabetes Care, 9(2), pp.

179–185. doi: 10.2337/diacare.9.2.179.

Schiøtz, M. L. et al. (2011) ‘Social support and self-

management behaviour among patients with Type 2

diabetes’, Diabetic Medicine, 29(5), pp. 654–661. doi:

10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03485.x.

Song, Y. et al. (2013) ‘Unmet Needs for Social Support

and Effects on Diabetes Selfcare Activities in Korean

Americans With Type 2 Diabetes’, Diabetes Educator,

38(1), pp. 77–85. doi:

10.1177/0145721711432456.Unmet.

Sorkin, D. H. et al. (2013) ‘Unidas por La Vida (United

for Life): Implementing A Culturally-Tailored,

Community-Based, Family-Oriented Lifestyle

Intervention’, Journal of Health Care for the Poor and

Underserved, 24(2), pp. 116–138. doi:

10.1353/hpu.2013.0103.

Soto, S. C. et al. (2015) ‘An Ecological Perspective on

Diabetes Self-care Support, Self-management

Behaviors, and Hemoglobin A1C Among Latinos’,

The Diabetes Educator, 41(2), pp. 214–223. doi:

10.1177/0145721715569078.

Souza, M. T. De and Carvalho, R. De (2010) ‘Integrative

review : what is it ? How to do it ? Revisão

integrativa : o que é e como fazer’, Einstein (São

Paulo), 8(1), pp. 102–106.

Tillotson, L. and Smith, M. (1996) ‘Locus of control,

social support, and adherence to the diabetes

regimen.\n’, Diabetes Education, 22(2), pp. 133–9.

Torenholt, R., Schwennesen, N. and Willaing, I. (2014)

‘Lost in translation-the role of family in interventions

among adults with diabetes: A systematic review’,

Diabetic Medicine, 31(1), pp. 15–23. doi:

10.1111/dme.12290.

Trief, P. M. et al. (2001) ‘The marital relationship and

psychosocial adaptation and glycemic control of

individuals with diabetes’, Diabetes Care, 24(8), pp.

1384–1389. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.8.1384.

Vongmany, J. et al. (2018) ‘Family behaviors that have an

impact on the self-management activities of adults

living with Type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and

meta-synthesis’, Diabetic Medicine, 35(2), pp. 184–

194. doi: 10.1111/dme.13547.

Wagner, E. H. et al. (2001) ‘Improving chronic illness

care: Translating evidence into action’, Health Affairs,

20(6), pp. 64–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64.

Walker, R. J. et al. (2015) ‘Quantifying Direct Effects of

Social Determinants of Health on Glycemic Control in

Adults with Type 2 Diabetes’, Diabetes Technology &

Therapeutics, 17(2), pp. 80–87. doi:

10.1089/dia.2014.0166.

Watanabe, K. et al. (2010) ‘The Role of Family

Nutritional Support in Japanese Patients with Type 2

Diabetes Mellitus’, Internal Medicine, 49(11), pp.

983–989. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.3230.

Weiler, D. M. and Crist, J. D. (2009) ‘Diabetes self-

management in a latino social environment’, Diabetes

Educator, 35(2), pp. 285–292. doi:

10.1177/0145721708329545.

Wen, L. K., Shepherd, M. D. and Parchman, M. L. (2004)

‘Family Support, Diet, and Exercise Among Older

Mexican Americans With Type 2 Diabetes’, The

Diabetes Educator, 30(6).

White, P. et al. (2009) ‘Understanding type 2 diabetes:

Including the family member’s perspective’, Diabetes

Educator, 35(5), pp. 810–817. doi:

10.1177/0145721709340930.

World Health Organisation (2002) Innovative care for

chronic conditions: building blocks for action: global

report, World Health Organisation. Geneva: WHO.

Zhou, B. et al. (2016) ‘Worldwide trends in diabetes since

1980: A pooled analysis of 751 population-based

studies with 4.4 million participants’, The Lancet.

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. Open Access article

distributed under the terms of CC BY, 387(10027), pp.

1513–1530. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00618-8

Family Support for Better Self Care Behavior Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

427