Are You Ready When It Counts?

IT Consulting Firm’s Information Security Incident Management

Maja Nyman and Christine Große

Department of Information Systems and Technology, Mid Sweden University, Holmgatan 10, Sundsvall, Sweden

Keywords: Security Awareness, Information Security Incident Management, IT Consulting, GDPR, NIS Directive.

Abstract: Information security incidents are increasing both in number and in scope. In consequence, the General Data

Protection Regulation and the Directive on security of network and information systems force organisations

to report such incidents to a supervision authority. Due to the growing of both the importance of managing

incidents and the tendency to outsourcing, this study focuses on IT-consulting firms and highlights their

vulnerable position as subcontractors. This study thereby addresses the lack of empirical research on

incident management and contributes valuable insights in IT-consulting firms’ experiences with information

security incident management. Evidence from interviews and a survey with experts at IT-consulting firms

focuses on challenges in managing information security incidents. The analyses identify and clarify both

new and known challenges, such as how the recent regulations affect the role of an IT-consulting firm and

how the absence of major incidents influences stakeholder awareness. Improvements of IT-consulting firm’s

incident management process need to address internal and external communication, the information security

awareness of employees and customers and the adequacy of the cost focus.

1 INTRODUCTION

Information and communication technology has

recently gained vital importance for organisations.

However, the benefits of technology use are

accompanied by the risk of becoming a target of

attacks on information security (InfoSec). This risk

is increasing due to the higher value and sensitivity

of information that organisations process (Ab

Rahman and Choo, 2015; Hove et al., 2014; Tøndel

et al., 2014). Here, an incident refers to an

unexpected or unwanted event that has a significant

probability of threatening the security of

information. For the concerned organisation, such an

incident can pose several negative consequences,

including economic loss, lost productivity, legal

consequences, impaired image and weakened

customer trust (Ahmad et al., 2012). Due to the

heightened occurrence of incidents, a structured

InfoSec incident management (ISIM) has developed,

which encompasses incident management,

awareness training, mitigation of vulnerabilities and

preparation activities (Ab Rahman & Choo, 2015;

Cusick and Ma, 2010). The development of ISIM

has generated several standards and guidelines

which provide assistance for the ISIM of

organisations but are often too general to be easily

implementable (Bailey et al., 2007). In addition, the

recently implemented General Data Protection

Regulation (GDPR), which has been the most

significant development in data protection in the past

20 years, created immense uncertainty among

organisations regarding how to fulfil the

requirements (O’Brien, 2016). The increased duty to

report incidents to a supervision agency has

prompted major issues, such as delays of more than

five days and up to a month (MSB, 2017).

Research has rarely examined or described how

organisations have implemented ISIM (Line, 2013).

Thus, there is a need for specific and adapted

guidance for organisations and encouragement of

further empirical research on ISIM in practice. The

outsourcing of IT-related services has become

normal in business today, and subcontractors are

more vulnerable to cyber attacks because they have

access to different customer data (EU, 2016b).

Nevertheless, there is a substantial lack of studies on

ISIM at such organisations (Hove et al., 2014). This

study aims to fill this knowledge gap and address the

challenges that IT consulting firms (with over 20

employees) encounter in the context of ISIM. Hence,

the study results contribute to the development of

26

Nyman, M. and Große, C.

Are You Ready When It Counts? IT Consulting Firm’s Information Security Incident Management.

DOI: 10.5220/0007247500260037

In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2019), pages 26-37

ISBN: 978-989-758-359-9

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

ISIM within other organisations and informs the

development of future theory. To investigate the

ISIM of IT consulting firms, this study pursues the

following research question: What challenges do IT

consulting firms experience with regard to ISIM,

new legal requirements and their specific position?

After this introduction, Chapter 2 delineates the

ISIM framework for this study. After the methods

section, the results that were obtained from Swedish

IT consulting firms highlight several challenges that

are associated with ISIM. After the discussion of

theoretical and practical implications, the conclusion

summarises the study and suggests further research.

2 INFORMATION SECURITY

INCIDENT MANAGEMENT

2.1 Standards and Framework

Many institutions have produced guidelines that are

based on international standards for ISIM, such as

ISO/IEC 27035:2016 and NIST SP 800-61 (Rev 2)

(hereinafter referred to as ISO and NIST,

respectively) (MSB, 2012; Tøndel et al., 2014).

ISO presents general concepts of ISIM and a

structured, five-phase process for handling incidents

and improvements of ISIM. Organisations of any

kind can apply this standard because the principles it

provides are generic (ISO, 2016). Although ISO is

not a complete guide, proper implementation can

reduce the negative consequences of an incident for

an organisation. Meanwhile, NIST assists

organisations with effectively structuring ISIM. The

content is generic in regard to platforms, operation

systems, protocols and applications (Cichonski et al.,

2012). Similar to ISO, NIST describes an ISIM

process, which NIST has condensed into four phases

and a sub-cycle to manage secondary incidents that

emerge from an initial incident.

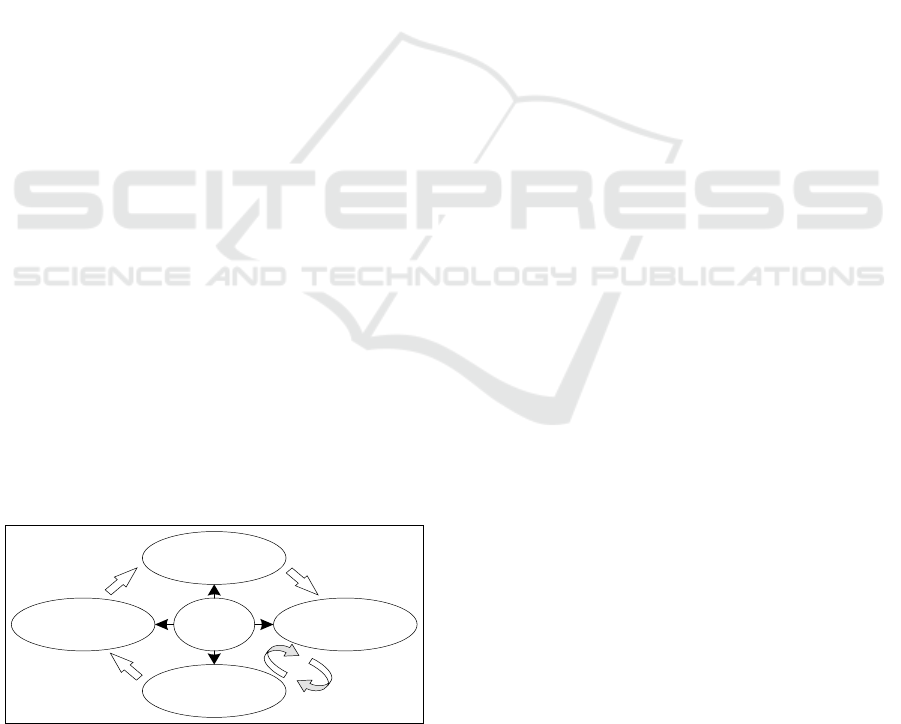

Figure 1: The ISIM Process (based on ISO and NIST).

This study applies a four-phase framework that

derives from the mentioned standards (see Figure 1).

The four phases are (1) planning and preparation, (2)

detection and reporting, (3) response and analysis

and (4) learning and improvement. In addition, the

centrum subsumes general issues that relate to the

entire ISIM process.

(1) The planning and preparation phase targets

the creation of capacity to manage incidents when

they arise. This phase ensures that InfoSec policies

are up to date at all organisational levels and that a

comprehensive ISIM policy and reliable incident

response team (IRT) exist. Such proceeding implies

not only that persons responsible for ISIM must be

involved and trained but also that all employees

must gain proper knowledge about correct

behaviour. Moreover, positive internal and external

relations are similarly essential for a refined ISIM in

terms of dedicating appropriate organisational and

technical resources to responsible teams. The

hardening of systems, applications and networks in

advance can minimise the attack surface of an

organisation. In this context, further tools warrant

consideration, such as alternative communication

tools and facilities, hardware or software,

documentation of systems and applied rules that are

necessary for incident analysis, and software to

mitigate incidents (Cichonski et al., 2012). Finally,

the established ISIM process requires proper testing

to ensure its functionality.

(2) The detection and reporting phase focuses on

activities during an incident, which include

detecting, identifying the character and scope and

estimating consequences of an incident. Although

the routines that the first phase prepares can support

a rapid response when the incident is of a known

type, the detection of an incident among the large

number of warnings that a monitoring system

produces requires experience and expert knowledge

within organisations (Cichonski et al., 2012). This

phase does not classify events but rather manually

and automatically collects information about system

vulnerabilities, events and decisions regarding

measurements. Such information must be

comprehensible and of a quality that enables

analyses during subsequent phases. Apart from such

recording of evidence, events that can affect InfoSec

need adequate reporting to responsible stakeholders

to inform further decision-making (ISO, 2016).

(3) The response and analysis phase entails

measurements to both understand the character of an

incident, including the cause and consequences, and

respond quickly to reduce the extent of the problem.

Both parts of this phase are intertwined and alternate

until the incident is successfully treated. Properly

defined policies and processes can establish an

(1) Planning and

Preparation

(2) Detection

and Reporting

(4) Learning and

Improvement

(3) Response

and Analysis

General

Issues

Are You Ready When It Counts? IT Consulting Firm’s Information Security Incident Management

27

appropriate base of information for decision-making

about mitigation measurements. The analysis is

founded on the information that was collected in the

previous phase. Thereby, it classifies the incident

and suggests measurements for response. Response

implements these measurements and accumulates

further information regarding the success of the

treatment, which provides additional input for

another analysis. A comprehensive documentation

of analyses, decisions and measurements is

advisable, for example to meet legal requirements,

record evidence and learn from both successes and

failures. In addition, predefined procedures should

guide each responsible person in an organisation in

acting properly during the information assessment,

incident classification and mitigation. Such

guidelines should include up-to-date information

about the notification of other stakeholders, resource

allocation, required documentation, treatment and

notification of completion. (ISO, 2016)

(4) The learning and improvement phase

develops ISIM within an organisation, which

includes all personnel to some extent. Attention

should be directed to lessons that are learned after

each large incident and regularly after small

incidents and events (Cichonski et al., 2012).

Discussions involve acquired knowledge of how and

when the incident emerged, which lacks of

knowledge and guidance appeared and which

measurements may help to prevent the system from

further occurrence of similar incidents.

Comprehensive documentation of the incident

management provides the basis for future

improvement of ISIM. This phase completes the

documentation with information on the performance

of organisational learning and on improvement

activities regarding ISIM, which can also facilitate

improvements to this phase and inter-organisational

collaboration during ISIM (ISO, 2016).

2.2 Legal Regulations

The GDPR, which has applied within the European

Union (EU) since 2018-05-25 (EU, 2016b),

addresses the protection of individual data and

information and the privacy of individuals. The

GDPR aims to synchronise the requirements for data

protection and privacy within the EU and to adapt

former laws to the demands of a more digitalised

society. The regulation concerns the citizenship of

an individual rather than the location of the data

storage (Tankard, 2016). Important changes regard

the following: establishing data portability, assessing

consequences of data breaches, reporting incidents

regarding personal data within 72 hours and

appointing a data protection officer. Moreover,

organisations can encounter costly penalties if they

do not fully meet the requirements. In particular, an

incident report to a national data protection agency

must contain information on the character, extent

and consequences of the incident as well as the

measures that have been performed to reduce

negative effects. (EU, 2016b)

The European Parliament has passed another

regulation, namely the directive on security of

network and information systems (NIS), which came

into force on 2018-05-10 (EU, 2016a). The NIS

applies to operators of digital services and other

critical infrastructure, such as energy and water

supplies, transportation, finance and health services.

The directive aims to improve the security level of

information systems and networks within the EU. In

accordance with the NIS, providers are now

responsible for preventing and managing incidents

in information systems and networks, contending

with risks and reporting incidents to a specific

agency. Concerned organisations must implement a

systematic and risk-based ISIM. Deviations from the

stated requirements can be subject to sanctions, but

the amount of such a penalty would depend on the

extent of the deviation. In particular, the NIS forces

providers to report incidents that have a significant

impact on the continuity of critical infrastructure or

digital services without any unnecessary delay. This

reporting involves even incidents at a subcontractor,

such as an IT consulting firm. Such a report must

comprehensively announce the character, extent and

consequences of the incident as well as the enacted

measures to mitigate a further spread and improve

ISIM. (EU, 2016a)

3 METHODICAL PROCEEDING

3.1 Case Selection

The initial literature review assisted with framing the

investigation and theoretical background for both the

interview study and the survey (Bryman and Bell,

2015). This study applied a mixed methods approach

in which the survey results broadened and

complemented the evidence that resulted from the

interview study. This methodical approach yielded a

deeper understanding of the ISIM of IT consulting

firms. For this purpose, this study selected three IT

consulting companies for data collection: one parent

company and two subsidiaries from a business group

that consists, apart from this parent company, of 70

ICISSP 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

28

subsidiaries in several European countries, including

Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland and Germany.

The subsidiaries employ 30 individuals on average.

Besides the parent company, this study examined

one subsidiary of this size and one that is four times

larger, which ensured proper variation in the case

selection. According to Denscombe (2014), a small-

scale study requires at least five interviews and 30

survey respondents to appear appropriate. In view of

this, the present study collected data from six top-

level experts in the field of ISIM as well as 47

respondents with varying experience. Based on the

collected data, the investigation achieves an

adequate depth of understanding, which it extends

with a broader comprehension of the particular

position of IT consulting firms. Table 1 presents the

participants and their affiliations.

Table 1: Selection of IT Consulting Firms and Participants

from a Swedish Business Group.

Firm

Partici

pant

Description

Company

A (CA)

Autonomous subsidiary to company

CC; IT consulting firm with 135

employees in Sweden

A1

Consultant manager for 13 years;

responsible for safety, security,

InfoSec and management

A2

Project manager for CA’s major

project and expert in customer ISIM

for three years

A3

Employee who works with InfoSec

and CA’s operations for three years

Survey

Total of 47 respondents with

varying experience and knowledge

Company

B (CB)

Autonomous subsidiary to company

CC; IT consulting firm with 25

employees in Sweden

B1

Consultant manager; responsible for

InfoSec management since 2017

B2

B1’s predecessor; responsible for

InfoSec and management from 2011

to 2017

Company

C (CC)

Swedish parent company of the

business group of 13 employees; the

entire group employs 2.100 people

in 70 autonomous subsidiaries.

C1

Employee at CC; responsible for

InfoSec and safety for the entire

group for five years

3.2 Data Collection

Information about the ISIM of IT consulting firms is

sensitive; therefore, this study employed interviews

as a main part of the mixed methods approach. Six

individual interviews were held with experts in the

field of InfoSec who were employed by three

companies. Each interview lasted between 40 and 70

minutes and was recorded and transcribed with

permission to facilitate subsequent analyses

(Denscombe, 2014). The majority of the semi-

structured interviews were conducted personally at

each interviewee’s ordinary place of work to ensure

that no external factors would influence the

individual’s perceptions. The point of departure for

interviews was the theoretical framework of this

study, which is based on standards and regulations in

the context of ISIM. Open-ended questions were

prepared in advance to consistently guide interviews

and allow interviewees to discuss and explain

particular issues if they appeared to be relevant to

the study (Johannesson and Perjons, 2014). Through

this proceeding, this study collected evidence that

clarifies the topic and addresses the research

question. Although the results of the interview

analyses are of primary importance, this study also

included a survey to broaden its knowledge base.

The survey complemented the interview study

and extended perceptions of interviewees to gain a

comprehensive view of the degree to which

employees who are not InfoSec experts are

conversant with the ISIM of their company. Since

previous research has considered answering closed

questions to be easy and practicable for respondents

(Denscombe, 2014), the survey applied six closed

questions. Two questions consisted of two sub-

questions, while one contained four. Of these 11

questions, three were binary, i.e. Yes or No, four

extended the binary choice with an indicator for

ignorance or irrelevance, i.e. N/A, and the remaining

four applied a Likert scale that spanned from one to

six. By omitting the neutral response option, the

study forced respondents to opt for one direction

(Croasmun and Ostrom, 2011), which heightened

the clarity of the results.

As in the interview study, the survey departed

from the theoretical framework. For stronger

validity, the survey included two questions that were

almost identical to determine whether participants

responded similarly to both. The survey originated

electronically, and participant A1 distributed a link

to 80 individuals who are employed by CA. To

obtain an appropriate number of responses, this

study surveyed the IT consulting company with the

largest number of employees of the three companies,

and it thereby excluded the employees of CB and

CC. After two weeks, the survey obtained a

satisfactory number of 47 responses, which

constitutes a sound response rate of 58.75%.

Are You Ready When It Counts? IT Consulting Firm’s Information Security Incident Management

29

3.3 Data Analysis

Recordings, transcripts and experiences during

interview situations were the basis for analysis in the

interview study. This analysis sought to clarify the

content (Schutt, 2015) and thereby nuance

understandings of how IT consulting firms navigate

ISIM. Departing from the framework and

questionnaire, the analysis arranged the evidence

from interviews in accordance with the four phases

of ISIM and further addressed general issues. To

strengthen the validity of this study, interviewees

received an opportunity to review the results of the

analysis and provide further considerations.

Therefore, the results emphasise challenges that IT

consulting firms encounter in ISIM and the recent

restrictions of regulations.

The survey yielded ordinal and nominal data,

which this study presents as the mode of each

dataset. Despite limitations to the mathematical

treatment of a mode, this study employs mode for its

resistance to outliers and ability to demonstrate

important information about the population under

investigation. By this representation, the analysis of

the survey results reveals the experience and

knowledge of employees in regard to selected

aspects of ISIM. A bar chart visualises the

quantitative results of the survey questions that

applied a Likert scale.

4 CHALLENGES IN INCIDENT

MANAGEMENT

4.1 Interview Results

4.1.1 Planning and Preparation Phase

The participants in the interview study discussed

challenges that relate to the ISIM phase planning

and preparation (see summary in Table 2).

Two participants reported difficulties with

integrating planning and preparation activities into

daily business, particularly in dedicating a full-time

person to InfoSec. They remarked that people who

work with these issues must function within several

roles, which leads to postponements. Both

respondents acknowledged challenges in prioritising

InfoSec, especially regarding the focus on costs and

chargeable hours within IT consulting firms.

The majority of interviewees stated that GDPR

poses challenges because it can accompany a larger

number of incidents. In particular, C1, A3 and B1

stressed the requirement of incident reporting within

72 hours. C1 conceded that the company had no

routine at the time to meet this requirement. One

reason that C1 reported was that only two

individuals had extensive knowledge of ISIM; thus,

their absence due to holidays would cause time-

related problems. Meanwhile, B1 discussed the fear

of misjudging the severity of an incident.

Specifically, a misjudged incident that later appears

to be more severe than initially perceived could pose

penalties for the company. B3 explained that costs

are an obstacle to the 72-hour requirement. Given

the example of Christmas holidays, B3 argued that a

firm could weigh the costs for extra wages against

the risk that an incident occurs. A3 noted that the

actual time that is available to an IT consulting firm

is significantly less than 72 hours, as an IT

consulting firm needs to inform its customers first.

Another challenge, as A3 reported, is the

maintenance of databases of personal data, which

improve test results on customers’ IT systems. Both

partners, i.e. an IT consulting firm and a customer,

must become aware of new regulations and that such

data may no longer be shared among partners. A2

expressed difficulties with comprehending GDPR,

which could lead to variation in understandings and

implementations regarding, for example, the degree

of severity of an incident that would oblige a

company to report. In view of the risk of severe

penalties, A1 and C1 acknowledged the importance

of adapting service contracts to ensure that the

responsibility for GDPR remains with the customer.

Many participants reported a lack of routines for

ISIM. A particularly problematic aspect is that

existing processes must be adapted to GDPR,

implemented before the regulatory deadlines and

finally obeyed by poorly informed employees.

Therefore, C1 identified training on incident

reporting as imperative for implementing such

adapted routines. Although A2 and B2 recognised

benefits of practicing ISIM in advance, they also

considered its preparation and execution to be

challenging because of high resource restrictions.

Budget restrictions are a reoccurring issue in the

ISIM of IT consulting firms. The participants

reported that they experience higher security needs

from customers, yet they struggle to convince

customers to pay for work on customer InfoSec.

Most often, insights arise late, and they have to

extend the contract post hoc because of the extra

time that such additional task will require. The

participants emphasised this as a critical challenge

because an incident for a customer within the system

that an IT consulting firm has developed and

implemented also has negative effects on the firm’s

ICISSP 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

30

reputation.

Table 2: Summary of the Perceived Challenges in the

ISIM Phase of Planning and Preparation.

Intervie

wee

Perceived Challenges

A1, A3

• Integrating routines and processes into

daily business; nobody works full time with

InfoSec

A1, A2,

A3, B1,

C1

• Avoiding incidents related to GDPR

B2

• Establishing routines related to GDPR that

all employees know and apply

• Lack of a computer system to record

incidents

A2 / B2

• Dedicating training time / lack of training

to prepare for incidents

B1

• Employees are not conversant in company

policies and company lacks some routines

• Lack of IRT; nobody has a qualification for

managing incidents

A2, A3,

C1

• Convincing customers to pay for InfoSec,

particularly urgent due to tightened

regulations

A1, C1

• Establishing proper customer contracts

regarding GDPR

4.1.2 Detection and Reporting Phase

Several issues that relate to the ISIM phase detection

and reporting emerged during the interviews. Table

3 represents the identified challenges.

All participants stated that the major issue in this

phase is the uncertainty among employees regarding

the characteristics of an incident and which aspects

must be reported. A1 observed a large variation in

which information is reported and explained that

employees sometimes report less important events

that cannot be classified as an incident by any

means, whereas serious incidents not always are

reported. Such lack of recording constitutes an issue

since the event will nevertheless emerge, e.g. orally,

and will then be hard to analyse. A3 viewed a major

problem in the companies’ routines. Employees tend

to contact A3 instead to self-report an incident,

which forces A3 to prepare the record; otherwise,

learning or following up later becomes impossible.

A3 imagined that this behaviour was due more to a

lack of awareness of proper execution of reporting

among employees than to inadequate knowledge of

procedures. In contrast, A2 stated that employees are

solution-oriented; however, improper

overconfidence could result in an insecure ISIM.

In the context of GDPR, A2, B1 and C1 stated

that they expect further obstacles in detecting and

reporting incidents due to extended legal

requirements and new types of incidents that may

arise. C1 mentioned two issues, overreporting

because of the fear of making mistakes and under-

reporting because incidents are not detected. Apart

from determining whether an incident has occurred,

insufficient clarity of policies renders employees

uncertain where to report it if such incident concerns

a customer, according to B1. In contrast, B2 stated

that the parent company provides clear policies

which declare that all incidents must be reported

centrally and that no local intermediaries exist. If

employees have questions, they should contact their

consulting managers, such as B1. B2 claimed that

employee training is neglected since B2 is no longer

responsible for the firm’s security.

C1 shared that the parent company is working to

reduce the embarrassment that employees may feel

when they report an incident, as these feelings can

promote undesirable behaviour that can yield serious

consequences. C1 emphasised that anyone can

encounter an incident. Since CA does not have any

opportunity for system monitoring, as A3 stated, the

parent company is further responsible for network

scanning and analyses. Therefore, A3 demanded

better detection activities from the central level.

Moreover, A1 stressed the difficulty and

importance of developing a reporting process that is

easy to perform but still includes all relevant aspects.

Otherwise, employees would not employ it. In

addition to A1, A3 and B1 acknowledged that their

existing reporting processes have a common

bottleneck: only one person has access to reported

incidents, which can become a severe issue if such

person is not working.

Table 3: Summary of the Perceived Challenges in the

ISIM Phase of Detection and Reporting.

Intervie

wee

Perceived Challenges

A1, A3,

B2 / A2,

B1, C1

• Uncertainty about what an incident is and

what must be reported among employees;

particularly challenging in the context of

GDPR

B1

• Unclear whom employees shall contact if

an incident occurs that affects a customer

C1

• Embarrassing to report incidents

A3

• Insufficient system scanning from central

level

A1

• Lack of an easy and adequate process for

incident reporting

A1, A3,

B1

• Bottleneck in the process for incident

reporting

Are You Ready When It Counts? IT Consulting Firm’s Information Security Incident Management

31

4.1.3 Analysis and Response Phase

In regard to the ISIM phase analysis and response,

participants emphasised the obstacles in Table 4.

Although CA has routines in place, A1 perceived

two challenging issues: to be solely responsible for

the escalation of an incident to the right stakeholder

and to gauge the extent to which the daily business

must be adapted. A1 reported that CA never had to

deal with an incident that affected a customer but

feared the gauging would be even harder, which A2

also considered. The matter of concern is the balance

between tightening security and continuing the daily

business; in this regard, even A3 noted a possible

difficulty. With documentation and policies, A2 and

A3 spotted insufficiency in prioritising, escalation

and response, and they suggested clarification of

how a responsible person must act, particularly in

response to different types of incidents. A3 found it

essential that these policies are also available,

known and practiced within CA. In addition to

enhanced policies, CA trained another individual to

decide on technical issues during incidents to reduce

the risk that only one single person is capable of

performing such a crucial task, according to A1, A2

and A3.

In contrast to CA, CB does not perform any

analysis or response to incidents; according to B2,

this is instead managed by the parent company.

Although CB detects and reports an incident to the

central level, B2 criticised the fact that no feedback

returns, so CB consequently does not know how and

when CC handles such incident. B2 suggested an

intermediate at CB to heighten attention and ensure

fast response to particularly meet the time

requirements of GDPR. In this regard, B2 blamed

the general focus on costs for the absence of such an

intermediator thus far. B1 identified a lack of

policies and processes for handling reported

incidents. In addition, B1 demanded a more

thorough documentation of incidents and mitigation

activities. B2 perceived a stronger security thinking

and focus on solving incidents quickly and

comprehensively if a customer is affected, whereas

this is rather disregarded in the own business.

C1 declared that CC is responsible for analysis

of and response to all incidents that happen at

subsidiaries in Sweden. In addition to the

subsidiaries’ manually reported incidents, CC

monitors the entire system of the business group.

The group is large in size and thus constantly

attacked, so CC filters irrelevant ones from the

permanently arising incident warnings. However, C1

perceived a potential threat in the inadequacy of

knowledge and experience, which may lead to

inappropriate decisions when an incident arises,

especially if substitutes are responsible for the initial

assessment.

Table 4: Summary of the Perceived Challenges in the

ISIM Phase of Analysis and Response.

Intervi

ewee

Perceived Challenges

A1, C1

• Escalation of incidents

A1, A2

• Gauging extent to which daily business must

be tightened in case of an incident, particularly

if it affects a customer

A2,

A3, B1

• Insufficient policies and routines for how

employees shall act and prioritise with regard

to different types of incidents

A3

• Making policies about routines and processes

available, known and practiced

B1

• Insufficient documentation of incidents and

mitigation activities

B2

• No local analysis and response due to costs,

which must be changed

• Lower security thinking on and prioritising of

internal data and incidents compared to

external issues, i.e. data and incidents related to

a customer

C1

• Lack of knowledge and training, especially

among substitutes

4.1.4 Learning and Improvement Phase

The fourth phase of ISIM concerns learning about

incidents and improvement of ISIM. The

interviewees reported particular problems which

prompt the challenges in Table 5.

A1 and A2 acknowledged that CA has

established a cross-functional group that discusses

mostly larger incidents during regular meetings. The

participants therefore emphasised the learning

opportunities that can stem from occasional events

or smaller incidents, particularly with regard to

avoiding larger incidents that easily can result from

the former. Despite these meetings, A1 noted the

challenge of allocating time for individual, in-depth

learning, which could also encourage an enhanced

feedback flow from the meetings to all employees.

In addition, A3 perceived opportunities to learn from

reoccurring patterns in attacks on the network, but

such opportunities are precluded by insufficient

feedback on incidents from the parent company.

According to B1, proper communication and

knowledge sharing about incidents with other

organisations would be a significant learning

opportunity. According to B2, CB does not conduct

any meetings to solely discuss incidents; rather, this

issue is only one point on the agenda.

ICISSP 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

32

In contrast, C1 stated that CC maintains a proper

process for the regular assessment of both small and

large incidents. However, C1 claimed that the major

issue is to decide how much of the information that

is discussed at assessment meetings should be

provided to employees. Since the sheer volume of

information can prompt employees to completely

stop reading such information, C1 perceived a

challenge in how much and which kind of

information to provide. Another issue that C1

acknowledged is the apparent ease of documenting

external knowledge, such as incidents and mitigation

activities, compared to preserving the internal

experience of a human expert in the field.

Table 5: Summary of the Perceived Challenges in the

ISIM Phase Learning and Improvement.

Intervi

ewee

Perceived Challenges

A1, A2

• Misjudging of small incidents and

extraordinary events that had the potential to

become an incident

A1

• Dedicating time to go through incidents

thoroughly

• Information sharing among all personnel

A3

• Lack of feedback from central level on

incidents that relates to networks

B1

• Insufficient external communication and

knowledge sharing

B2

• Lack of meetings only dedicated to incidents

C1

• Balancing the content and scope of employee

information for enhancing awareness,

commitment and compliance to policies

• Organisational knowledge and experience

management

4.1.5 General Issues

In regard to the question of which issues participants

experienced that apply to ISIM phases, several

considerations emerged that substantiate the

challenges in Table 6.

All participants emphasised that high awareness

among employees is significant for both InfoSec in

general and internal policies and processes in

particular. Because of the business focus of IT

consulting, all employees possess sufficient

knowledge of technology and InfoSec. Although all

new personnel undergo InfoSec training, the

majority of participants noted that it would be

desirable for all employees to regularly repeat the

content. According to B2, obtaining a high security

level requires that such content is up to date and

employees receive regular reminders; otherwise,

there is the risk that InfoSec issues fall behind the

core business focus. A3 and C1 noted that even

though employees have knowledge of InfoSec, many

attacks are advanced and well performed, which

makes an intrusion hard to detect, even for experts.

Classified customer data provide another issue that

is associated with employee awareness and training.

Particularly, if an escalation of a detected incident

must target the right stakeholder, then the initial

classification of such incident requires adequate

knowledge, according to C1. A3 claimed that CA’s

employees have low maturity in terms of open

networks at public places. Despite a discussion of

risks, employees do not recognise them, as A3

noted, particularly when using mobile devices. A3

acknowledged that employees understand the value

of information, such as sensitive information that

employees share via e-mail, on a computer but not

on a mobile phone. Although CA sends e-mails in a

secure manner, it cannot ensure that customers also

do this, which renders it impossible for an employee

to properly delete sensitive e-mail. A2 mentioned

that mobile devices are generally more insecure than

computers.

Another risk emerged from the interviews: for

the benefit of a strong focus on customer demands,

IT consulting firms may neglect internal demands.

According to A1, it is easy to disregard work on

internal security, partly to avoid costs but mainly out

of eagerness to assist customers with their problems.

A1 explained that the implementation of GDPR has

recently accelerated this issue to ensure their own

compliance with GDPR in addition to the

compliance of their customers. B1 reported that this

tendency towards enhanced awareness of customer

demands also extends to incidents. A2 shared that

since customer systems are often more critical, CA

seeks higher accuracy in their assessment than in

assessments of their own systems. Such imbalance is

completely normal according to A2, as such

assessment produces further business opportunities

for an IT consulting firm. However, most

participants remarked that the will to fulfil customer

demands has even led to advancements of intern

InfoSec. Customers who require a high security

standard enforce IT consulting firms to devote effort

to security management of both internal and

customer systems. Participant A3 claimed that IT

consulting firms unfortunately focus on intern

InfoSec management first if it becomes inevitable

rather than not seldom first when an incident occurs.

As A2 concluded, ‘it seems that we have much more

to do in the field of IT security, but it is hard to know

exactly what before something has happen’.

Three of the participants considered a focus on

Are You Ready When It Counts? IT Consulting Firm’s Information Security Incident Management

33

chargeable hours at IT consulting firms. A1

explained that since InfoSec management is a

continuous task, it sometimes seems difficult to

prioritise it in daily work, particularly when InfoSec

is not the core business. A3 added that IT consulting

firms prioritise tasks that generate profit, so InfoSec

may receive lower priority. B2 added that security is

easily forgotten and rarely prioritised by CB for

time- and cost-related reasons.

According to A3, employees never experienced a

major incident in CB. Because of this lack of

experience, employees cannot comprehend the

importance of thorough reporting.

Both participants at CB experienced a lack of

communication with the parent company regarding

particular aspects. For example, in reference to the

GDPR, B1 found it unclear whether CC would

provide common policies or if each subsidiary is

responsible for creating their own. B2 expressed

dissatisfaction because CB does not know how CC

handles the reported incidents.

Table 6: Summary of the Perceived Challenges Generally

Applicable to ISIM.

Intervie

wee

Perceived Challenges

A1, A2,

A3, B1,

B2, C1

• Obtaining high awareness of InfoSec

among employees

A1, A2,

A3, B2

• Excessively strong customer focus that

neglects internal demands

A1, A3,

B2

• Focus on chargeable hours hampers the

implementation of a continuous work on

InfoSec

A2, A3

• Lack of (experience with) major incidents

B1, B2

• Insufficient communication with parent

company

4.2 Survey Results

The survey compiled evidence from 47 employees at

CA. Almost three out of four respondents

(74%) categorised their knowledge on InfoSec as

insufficient, whereas only slightly more than a third

of the employees (26%) perceived it to be

appropriate.

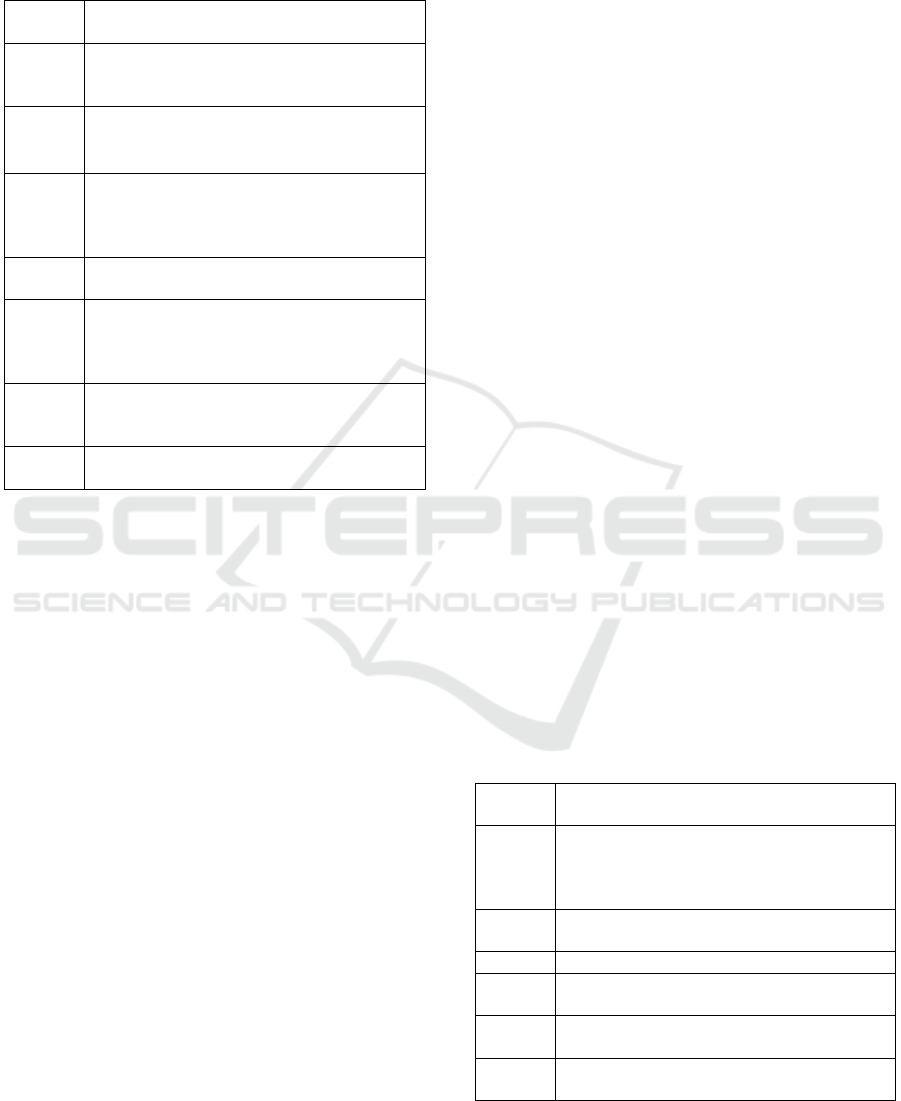

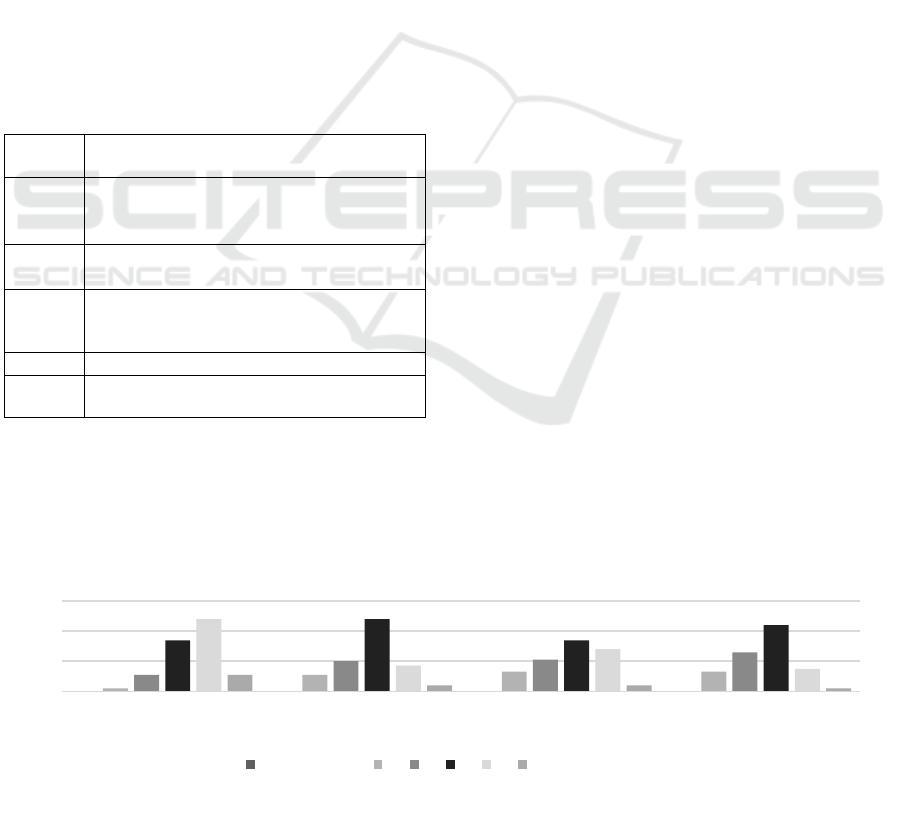

Figure 2 visualises the perceived level of

knowledge of several issues in the context of ISIM.

The respondents selected their particular level of

knowledge according to a scale that ranged from (1)

very limited to (6) deep knowledge.

Employees expressed stronger confidence in

their knowledge of incident avoidance than of

incident detection, reporting requirements and

company policies. The results indicate that 13% of

respondents selected an answer to Q1 from the lower

half of levels (1-3); in comparison, this figure was

31%, 34% and 39% for Q2, Q3 and Q4,

respectively.

When asked if recent changes in regulations,

namely GDPR and NIS, would affect the judgement

of the necessity to file an incident report, 11%

expected a more difficult assessment, 42%

anticipated no effects and the remaining 47% did not

know.

Regarding incident reporting, the majority of

respondents had knowledge of how and to whom to

report an incident. Even though 94% of respondents

knew how to act in accordance with internal ways of

reporting, this level of knowledge fell to 70% in

regard to incidents that affect a customer. However,

89% of the respondents knew where information on

their company’s ISIM was stored, while only 11%

did not know. Reporting an incident can be

challenging, particularly if an employee or a

colleague has caused the incident. To the question of

whether a respondent would hesitate to report an

incident that she or he has caused, 9% answered

‘Yes’. The difficulty of reporting under such

circumstances may illustrate answers to the follow-

up question of whether a respondent would prefer an

anonym: 21% answered Yes, 66% selected

Irrelevant and 13% said No.

Figure 2: Levels of Knowledge on ISIM Issues according to the Respondents on the Survey.

0

0

0

0

2

11

13

13

11

20

21

26

34

48

34

44

48

17

28

15

11

4

4

2

0

20

40

60

Q 1: … HO W Y O U C A N

A V O ID A N I N C I D E N T

Q 2: … D E T E C T I N G A N

I N C I D E N T

Q 3: … J U D G I N G I F A N

I N C I D E N T NE ED

R E P OR T I NG

Q 4: … YO U R C O M P A NY ' S

P OL I C I E S A ND

G U I D E L I NE S O N I S I M

PERCEIVED KNOWLE DGE ON ...

1 - Very limited 2 3 4 5 6 - Deep knowledge

ICISSP 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

34

5 DISCUSSION

This study evidences that ISIM poses challenges for

IT consulting firms, whose various issues impact

both their own business and that of their customers.

Among these issues, certain challenges warrant

particular attention in this study of three Swedish

consulting firms:

(1) A strong cost focus

(2) Uncertainty among employees due to lack of

knowledge of the nature and management of an

incident

(3) Inter-organisational collaboration

(4) Trust in technical solutions

(5) Inadequate documentation and knowledge

management

(6) Insufficient understanding of and adaption to

legal requirements

First, InfoSec competes with other profit-

producing activities, which results in a low priority

of InfoSec prior to an incident. This study thereby

reinforces the findings of Werlinger et al. (2009),

who have reported that organisations tend to

diminish the priority of InfoSec in response to costs.

Although the interviews emphasise the

establishment of training opportunities for

improving ISIM, such training requires preparation

and time for execution, which may be deferred

because of costs. Bartnes et al. (2016) have also

reported such low priority of training from their

research on ISIM in the electricity sector. The

consequences of such cost focus are apparent in the

example of company B, which lacks documentation,

processes and routines as well as personnel and

computer support for ISIM because of costs to

implement a proper ISIM. Another consequence of

the cost focus is that IT consulting firms value the

InfoSec of customer systems more than that of the

internal systems. This imbalance stems from efforts

to maintain valuable relations with customers and a

sober image as an enabler of future business.

However, enhanced awareness of InfoSec towards

customers results in stronger requirements, which

forces IT consulting firms to improve their

competence in InfoSec management.

Second, all participants in this study reported

some kind of uncertainty with regard to the nature

and management of an incident. Detecting and

understanding that an incident is happening

appeared likewise to be a challenge, as it involved

knowing when and which information an employee

must report, to whom it must be reported, and which

measures to subsequently follow. Such uncertainty

implies that policies and training opportunities are

lacking, insufficient or not properly shared within

the organisation (Hove et al., 2014; Line, 2013).

This study further evidences that employees have a

tendency to underestimate small incidents (Ahmad

et al., 2012; Bartnes et al., 2016). However, such

events should be used to analyse how to avoid the

advancement of a small-to-large incident. Since the

companies in this study admitted that large incidents

have not yet occurred, their lack of experience can

explain their ignorance of the importance of such

analysis for organisational learning. Another reason

for underestimation could be the focus on costs that

implies that IT consulting firms do not spend much

effort on small events. Moreover, the participants

highlighted the difficulty of transferring implicit

knowledge from ISIM experts into the organisation.

A solution could be the simultaneous involvement of

experts and novices in the ISIM process to learn in

praxis from each other (Werlinger et al., 2009) and

to avoid knowledge loss when an expert leave the

organisation.

Third, the IT consulting firms in this study

claimed that inter-organisational collaboration is not

a substantial issue in their businesses. Nevertheless,

in terms of managing an incident, the evidence

conveys that deciding to shut down a customer

system in response to a severe incident is a

seemingly uncomfortable situation. Although all

participants emphasised the utmost priority of

security, they also acknowledged the benefit of

maintaining as much service as possible. From this

discrepancy stems an ambiguity that complicates the

decision of appropriate measures and the

communication of the necessary activities to a

customer. Flaws in such communication can affect

the external view of a company and, thereby, its

future business opportunities. It therefore appears

essential to establish reliable customer relations. The

standards for ISIM further suggest the use of such

inter-organisational relations for the exchange of

knowledge and experiences. This study could not

identify such trustful relations in practice, which

only one participant viewed as a problem. However,

a deeper inter-organisational knowledge exchange

could strengthen customer relations and improve the

ISIM for both partners.

Fourth, in contrast with previous research

(Werlinger et al., 2009; Werlinger et al., 2010), this

study could not confirm the argument that warnings

that IT monitoring systems generate are difficult to

handle because of their number and different

characters. A reason is that the parent company

solely maintains the monitoring of the entire system

and further purchases a service to filter the generated

Are You Ready When It Counts? IT Consulting Firm’s Information Security Incident Management

35

warnings. In addition, the parent company performs

minimal system scanning, which thus produces

fewer warnings. Nevertheless, future challenges can

emerge from this trust in technical solutions. For

instance, an incident that remains undetected for a

longer period of time can pose massive

consequences. In addition, this study indicates that

the subsidiaries have little knowledge of the

particular results of the system monitoring.

Improvements to communication and knowledge

sharing within organisations regarding benefits and

limitations of technical solutions could enhance

employee awareness of ISIM. As the interviews

highlight, experts with technical knowledge are rare

in the subsidiaries. Moreover, their knowledge is not

well documented, which can elevate to a challenge

in situations that require particular technical

experience (Werlinger et al., 2008).

Fifth, the lack of proper documentation is a

prolonged hindrance to adequate knowledge

management and sharing both within and between

organisations. Even if standards and previous

research continuously emphasise the importance of

proper incident documentation, this study reveals

that this aspect constitutes a major challenge to IT

consulting firms throughout the ISIM process. This

issue includes insufficient knowledge about the

following subjects:

Ways of reporting (Hove et al., 2014)

Responsible persons within the organisation and

the customers

Which aspects to document

The importance of recording

Handling a major incident (Jaatun et al., 2008)

Ways of analysing and responding to an incident

Policies, processes and guidelines

Means of communication and feedback

The lack of documentation and knowledge

cultivates uncertainty among employees.

Improvements should address the mentioned

knowledge gap to advance employee awareness of

appropriate behaviour and mitigation measures.

Such organisational learning must even involve

learning from failure and wrong decisions; therefore,

a proper documentation of both causes and

consequences is an essential precondition for

continuous organisational learning. Moreover, such

documentation must contain adequate content and be

accessible for all personnel with respect to the

determined security levels, which in turn demands

previous consideration of employee security levels.

This study reveals that future training efforts should

particularly address the secure usage of mobile

devices and public networks. In addition, according

to the interviews, meetings for discussing small

incidents and extraordinary events could enhance

employee compliance, awareness and competence.

Finally, advances in regulations introduce

another challenge to IT consulting firms. The

requirements of GDPR and NIS provoke uncertainty

among persons who are responsible for InfoSec.

Since these regulations are open to interpretation,

policies, guidelines and service-level agreements

must adapt to new and future changes in legal

requirements. The results evidence that responsible

persons at IT consulting firms are extensively

informed of GDPR and the possibly costly

consequences of insufficient compliance, which may

account for the recent high priority of this issue.

Experts in the field of InfoSec anticipate that GDPR

impacts the detection and reporting of incidents to a

larger extent than employees of IT consulting firms.

Moreover, this study indicates that organisations

currently focus solely on GDPR; this one-sided

orientation implies that the requirements of the NIS

risk becoming irrelevant. For IT consulting firms,

cost focus may be an influencing factor of this

orientation, as GDPR entails costly penalties while

the NIS does not.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This study addresses the gap in empirical research

on IT consulting firms’ management of InfoSec

incidents. In particular, it has examined challenges

that organisations perceive with respect to their

specific position as a subcontractor. The evidence

from interviews and a survey of InfoSec experts and

employees at IT consulting firms has highlighted

obstacles in the context of ISIM as discussed in

detail throughout this paper. These concerns include

communication issues, the cost focus of companies,

the lack of experience with large incidents, weak

awareness of InfoSec and inadequate comprehension

of documentation, policies, processes and

guidelines. Moreover, the recently implemented

regulations, namely GDPR and NIS, pose further

challenges for IT consulting firms, such as the

correct interpretation of regulations, the fulfilment of

requirements for timely reporting and the adaptation

of service-level agreements and policies to demands.

By demonstrating these challenges, this study

contributes to future developments in the ISIM field

in both theory and practice. Since no prior research

has focused specifically on GDPR or IT consulting

firms, the results constitute a novel contribution to

the body of knowledge in the InfoSec management

ICISSP 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

36

field. To substantiate the findings of this study,

further research must address the classification of

challenges for organisations in general. Therefore,

future research could extend the data collection to a

larger number of participants, companies and

branches for comparison. However, the enhanced

understanding of the position and challenges of IT

consulting firms with regard to ISIM provide

valuable insight for companies that want to improve

their internal and inter-organisational ISIM.

REFERENCES

Ab Rahman, N. H., and Choo, K.-K. R. (2015). A survey

of information security incident handling in the cloud.

Computers & Security, 49, 45–69.

Ahmad, A., Hadgkiss, J., and Ruighaver, A. B. (2012).

Incident response teams – Challenges in supporting

the organisational security function. Computers &

Security, 31(5), 643–652.

Bailey, J., Kandogan, E., Haber, E., and Maglio, P. P.

(2007). Activity-based management of IT service

delivery. In E. Kandogan (Ed.), Symposium on

Computer human interaction for the management of

information technology. New York: ACM.

Bartnes, M., Moe, N. B., and Heegaard, P. E. (2016). The

future of information security incident management

training: A case study of electrical power companies.

Computers & Security, 61, 32–45.

Bryman, A., and Bell, E. (2015). Business research

methods (Fourth edition). Oxford: University Press.

Cichonski, P., Millar, T., Grance, T., and Scarfone, K.

(2012). NIST 800-61, Revision 2: Computer security

incident handling guide. Gaithersburg, MD: National

Institute of Standards and Technology.

Croasmun, J. T., and Ostrom, L. (2011). Using Likert-

Type Scales in the Social Sciences. Journal of Adult

Education, 40(1), 19–22.

Cusick, J. J., and Ma, G. (2010). Creating an ITIL inspired

Incident Management approach: Roots, response, and

results. In L. P. Gaspary (Ed.), 2010 IEEE/IFIP

Network Operations and Management Symposium

workshops (pp. 142–148). Piscataway, NJ: IEEE.

Denscombe, M. (2014). The Good Research Guide: For

Small-Scale Social Research Projects (5th ed.).

Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Education.

European Union (EU) (2016a). Directive 2016/1148 of the

European Parliament and of the Council of 6 July

2016 concerning measures for a high common level of

security of network and information systems across

the Union.

European Union (EU) (2016b). Regulation 2016/679 of

the European Parliament and of the Council of 27

April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with

regard to the processing of personal data and on the

free movement of such data, and repealing Directive

95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation).

Hove, C., Tårnes, M., Line, M. B., and Bernsmed, K.

(2014). Information Security Incident Management:

Identified Practice in Large Organizations. In F.

Freiling (Ed.), 8th Int Conf on IT Security Incident

Management and IT Forensics (pp. 27–46).

Piscataway, NJ: IEEE.

International Organization for Standardization (ISO)

(2016). ISO/IEC 27035:2016: Information technology

-- Security techniques -- Information security incident

management.

Jaatun, M. G., Albrechtsen, E., Line, M. B., Johnsen, S.

O., Wærø, I., et al. (2008). A Study of Information

Security Practice in a Critical Infrastructure

Application. In C. Rong, M. G. Jaatun, J. Ma, F. E.

Sandnes, & L. T. Yang (Eds.), Lecture Notes in

Computer Science: Vol. 5060. Autonomic and trusted

computing (pp. 527–539). Berlin: Springer.

Johannesson, P., and Perjons, E. (2014). An introduction

to design science (1. Aufl.). Cham: Springer.

Line, M. B. (2013). A Case Study: Preparing for the Smart

Grids - Identifying Current Practice for Information

Security Incident Management in the Power Industry.

In H. Morgenstern (Ed.), 7th Int Conf on IT Security

Incident Management and IT Forensics (pp. 26–32).

Piscataway, NJ: IEEE.

O’Brien, R. (2016). Privacy and security. Business

Information Review, 33(2), 81–84.

Schutt, R. K. (2015). Investigating the social world: The

process and practice of research (8.ed.). Thousand

Oaks, Calif.: Sage.

Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency (MSB) (2012).

Nationellt system för it-incidentrapportering. (DN:

2012-2637).

Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency (MSB) (2017).

Årsrapport it-incidetnrapportering 2016. (DN 2016-

6304-7).

Tankard, C. (2016). What the GDPR means for

businesses. Network Security, 2016(6), 5–8.

Tøndel, I. A., Line, M. B., and Jaatun, M. G. (2014).

Information security incident management: Current

practice as reported in the literature. Computers &

Security, 45, 42–57.

Werlinger, R., Hawkey, K., and Beznosov, K. (2009). An

integrated view of human, organizational, and

technological challenges of IT security management.

Information Management & Computer Security, 17(1),

4–19.

Werlinger, R., Hawkey, K., Muldner, K., Jaferian, P., and

Beznosov, K. (2008). The challenges of using an

intrusion detection system. In L. F. Cranor (Ed.),

Proceedings of the 4th symposium on Usable privacy

and security (p. 107). New York: ACM.

Werlinger, R., Muldner, K., Hawkey, K., and Beznosov,

K. (2010). Preparation, detection, and analysis: The

diagnostic work of IT security incident response.

Information Management & Computer Security, 18(1),

26–42.

Are You Ready When It Counts? IT Consulting Firm’s Information Security Incident Management

37