Applying UTAUT Model for an Acceptance Study Alluding the Use of

Augmented Reality in Archaeological Sites

Anabela Marto

1

, Alexandrino Gonc¸alves

1

, Jos

´

e Martins

2

and Maximino Bessa

2

1

ESTG, CIIC, Polytechnic Institute of Leiria, Leiria, Portugal

2

ECT UTAD, Vila Real, Portugal

Keywords:

Acceptance of Technology, Augmented Reality in Archaeology, Cultural Heritage, UTAUT.

Abstract:

Looking forward to enhance visitors’ experience among cultural heritage sites, the use of new technologies

within these spaces has seen a fast growth among the last decades. Regarding the increasing technological

developments, the importance of understanding the acceptance of technology and the intention to use it in

cultural heritage sites, also arises. The existing variety of acceptance models found in literature relatively to the

use of technology, and the uncertainty about selecting a suitable model, sparked this research. Accordingly, the

current study aims to select, evaluate and analyse an acceptance model, targeted to understand the behavioural

intention to use augmented reality technology in archaeological sites. The findings of this research revealed

UTAUT as a suitable model. However, regarding the collected data, some moderators’ impact presented

in the original study may change significantly. In addition, more constructs can be considered for wider

understandings.

1 INTRODUCTION

The use of technologies within cultural heritage sites

has been prospected in the last decades aiming to bet-

ter fulfil visitors’ expectations. The implementation

of a new given technology among cultural heritage

sites differs depending on the sort of space itself. The

current study swell on archaeological spaces, regard-

ing to their nature of being outdoors environments,

usually with scarce access to technological solutions

for exploring these environments.

Due to the technological developments among the

last few decades, people are now allowed to access

technology almost everywhere, through handy de-

vices such as smartphones or tablets. Accordingly,

some technological solutions, inter alia, Augmented

Reality (AR), can be experienced in archaeological

spaces, as long as, visitors have the interest and the

conditions to do so.

In order to understand users’ behaviour regarding

the use of AR in archaeological sites, a literature re-

view is made, and an acceptance of technology study

is presented in the current study. Aiming to identify

a suitable model to evaluate the use of this technol-

ogy for archaeological sites, this study checks the ef-

fectiveness of a given theoretical model to understand

users’ perspective.

A vast diversity of models and theories have been

proposed by researchers, looking forward to under-

stand individuals’ behaviour in different contexts.

Thus, researchers have been improving these propos-

als combining them and, thereby, formulating new

models, in order to find better solutions for each area

of work.

Considering the use of AR in archaeological sites,

the available models of the acceptance of technology

were analysed and the Unified Theory of Acceptance

and Use of Technology (UTAUT) was selected. Ac-

cordingly, the current study presents a review of mod-

els and theories related to acceptance of technology

studies, as well as, implements UTAUT model to un-

derstand user’s behaviour regarding to the use of AR

in archaeological sites.

2 STATE OF THE ART

This literature review is divided in two main topics: 1)

an overview related to the most common models pro-

posed to evaluate the acceptance and intention to use

technology, and 2) a scope of previous studies regard-

ing to their choices considering the available models

in the literature.

Marto, A., Gonçalves, A., Martins, J. and Bessa, M.

Applying UTAUT Model for an Acceptance Study Alluding the Use of Augmented Reality in Archaeological Sites.

DOI: 10.5220/0007364101110120

In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications (VISIGRAPP 2019), pages 111-120

ISBN: 978-989-758-354-4

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

111

2.1 Acceptance of Technology Models

Trying to comprehend users’ acceptance and intention

to use technologies, a variety of models and theories

have been developed in order to unravel this relation

between users and technology. An understanding re-

lated to the adoption of behaviours has been provided

by the Theory of Reasoned Action (Fishbein, 1979;

Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980). The authors stated that

measuring the behavioural intention, it is possible to

predict the performance of any voluntary act.

Building on this model, which has been largely

used among the years to predict behavioural inten-

tions, one of the most substantial and influential theo-

ries of human behaviour, the Technology Acceptance

Model (TAM), was developed (Davis, 1986). This

model describes the motivational process mediating

system characteristics and user behaviour, and relat-

ing individual choices when adopting or not a tech-

nology when performing a task. For this analysis,

measures related to characteristics of the system and

capabilities, are made in order to relate it with users’

motivation to use the system, which can affect their

actual system use or non-use. A theoretical exten-

sion of TAM was presented as TAM 2 (Venkatesh

and Davis, 2000) which included additional theoret-

ical constructs embracing social influence processes

and cognitive instrumental processes. This accep-

tance model covers the evaluation of constructs such

as perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, inten-

tion to use, and the actual usage behaviour. TAM 3

(Venkatesh and Bala, 2008) come out from the com-

bination of TAM 2 with the model of the determi-

nants of perceive of use, creating new relationships,

focused on interventions regarding potential pre- and

post-implementations.

Despite the large number of studies conducted

aiming to understand factors that contribute to suc-

cessful implementations of technology, DeLone and

McLean looked at information system success as un-

achievable. Thus they proposed the DeLone and

McLean (D&M) Information Systems (IS) Success

Model as a framework and model for measuring the

complex-dependent variable in IS research, through

six categories: system quality, information quality,

use, user satisfaction, individual impact, and organi-

zational impact (DeLone and McLean, 1992). This

model was updated in 2003 attempting to capture

the multidimensional and interdependent nature of IS

success (DeLone and McLean, 2003). Service Qual-

ity was added and stated as an important dimension

of IS success given the importance of IS support, es-

pecially in the proposed case study: e-commerce en-

vironment.

Consistent with DeLone and McLean proposal in

1992, a model called the Technology-to-Performance

Chain was proposed in 1995 (Goodhue et al., 1995).

This approach stresses the linkage between con-

structs, reflecting the impact of information technol-

ogy on performance. The importance of a construct

known as Task-Technology Fit (TTF) on performance

impacts is highlighted. TTF models explicitly in-

clude task characteristics, as the examples proposed

in the Technology-to-Performance Chained, implying

the matching of capabilities of the technology with

the demands of the task. A common addition to TTF

models are individual abilities, such as computer lit-

eracy, where its perceive can be negatively affected

between task and technology (Goodhue, 1995).

Among new approaches, which have been blended

several models and theories striving for proposing

new and more suitable models to better understand

the acceptance of technology, it is found a clear exam-

ple of these combinations: the Unified Theory of Ac-

ceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), proposed

by Venkatesh et al. in 2003 (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

This proposal unified eight theories and models of

individual acceptance, namely, the Theory of Rea-

soned Action (proposed in 1988), TAM (described

above), Motivational Model (proposed in 1992), The-

ory of planned Behaviour (proposed in 1991), Com-

bined TAM and Theory of Planned Behaviour (1995),

Model of PC Utilisation (proposed in 1977), Innova-

tion Diffusion Theory (1995), and Social Cognitive

Theory (proposed in 1986). In their approach, they

pointed out four constructs registered as significant

to determine the behaviour intention of individuals

to use a technology: performance expectancy, effort

expectancy, social influence, and facilitating condi-

tions. These constructs were associated with indi-

vidual differences – age, gender, voluntariness, and

experience – as moderators on behavioural intention

to use a technology. The UTAUT 2, presented in

2012 (Venkatesh et al., 2012), provided three new

constructs, namely, hedonic motivation, price value,

and habit.

2.2 Acceptance of Technology Case

Studies

The applicability of these models and theories has

been a subject of study in order to accomplish a more

accurate evaluation related to the degree of accep-

tance and, hence the use of technology in diverse act-

ing areas.

Considering some recent and relevant studies, in

2010, Usoro et al. combined TAM and TTF to explore

the user acceptance and use of tourism e-commerce

HUCAPP 2019 - 3rd International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

112

websites (Usoro et al., 2010). The UTAUT 2 model

was used to understand online purchase intentions

and actual online purchases (Escobar-Rodr

´

ıguez and

Carvajal-Trujillo, 2014). The usage of AR for educa-

tion was apprehended using the TAM model (Ib

´

a

˜

nez

et al., 2016). The users’ acceptance and use of AR

mobile application in Meleka – tourism sector – was

evaluated using the UTAUT model (Shang et al.,

2017). The behavioural intention to use virtual re-

ality in learning process was evaluated proposing the

UTAUT model (Shen et al., 2017). A study for ac-

ceptance of AR application within the urban heritage

tourism context in Dublin, proposed the TAM model

(tom Dieck and Jung, 2018).

Regarding to cultural studies, the understanding

of cultural factors is important to highlight since they

play a significant role, praising the necessity to con-

sider cultural aspects as influent elements. Cultural

moderators were taken into account among several

studies related to acceptance and use of technology

(e.g., (Tam and Oliveira, 2017), (Venkatesh et al.,

2016)). Others, specifically target to ascertain cultural

differences, such as (Ashraf et al., 2014) and (Tarhini

et al., 2015), which helps to understand how different

cultures react differently to the same proposals.

The acceptance of each technology may require

specific requirements for its study. Therefore, a fo-

cused study regarding to the acceptance of augmented

reality in heritage contexts was made (from 2012

up to now) and, the list of found results, hitherto,

is not very extensive. Table 1 presents some of

the acceptance studies accomplished, The acceptance

model used and the sample size are specified. Ques-

tionnaires were the evaluation instrument used in all

shown studies. An exception was found in one study

(tom Dieck and Jung, 2018), which used one-to-one

interviews as an evaluation instrument.

Regarding the results presented in table 1, TAM

model was the most common model used by re-

searchers. UTAUT (or UTAUT 2) and DeLone &

McLean’s are also frequent choice. Sample sizes,

when present, are between 44 and 241 participants.

3 ACCEPTANCE MODEL

ADOPTION

To understand individuals’ acceptance of aug-

mented reality technology among archaeological

sites, UTAUT model was implemented and a ques-

tionnaire was created. In this section, the variables

in study, hypotheses and the results obtained are pre-

sented.

Table 1: Previous acceptance of augmented reality technol-

ogy studies found, from 2012 until now.

Context Model Sample Reference

AR in Cultural

Heritage

TAM 200 +

42

(Haugstvedt

and Krogstie,

2012)

AR interactive

technology to

enable con-

sumers to try

on clothes

online

TAM 220 (Huang and

Liao, 2015)

AR in natural

park

D&M 241 (Jung et al.,

2015)

AR for tourism:

destinations

and attractions

TAM (not

found)

(Chung et al.,

2015)

AR Travel

Guide

UTAUT2 105

(Kourouthanas-

sis et al.,

2015)

AR for edu-

cation: help

engineering

students to

solve problems

TAM 122 (Ib

´

a

˜

nez et al.,

2016)

Mobile AR

app to show

campus-related

information on

a map

UTAUT

+

D&M

(not

found)

(Alqahtani and

Kavakli, 2018)

AR in urban

heritage

tourism

TAM 44 (tom Dieck and

Jung, 2018)

3.1 Acceptance Model Selection

The knowledge related to the most significant accep-

tance models presented in the previous chapter al-

lowed to select an acceptance model to suit the case

of study of this research. Since the requirements of

this study to seek a prediction of behaviours, where

participants have no access to experience a prototype,

the unified theory of acceptance and use of technol-

ogy (UTAUT) and its constructs related with expected

behaviours, seemed to better fit this study needs. The

new constructs proposed for UTAUT 2 appeared to

be misplaced because the current case study is not fo-

cused in commerce.

Therefore, the constructs and respective items are

described bellow, as well as, the moderators consid-

ered.

The independent variables (IV) evaluated in the

current study are Performance Expectancy (PE), Ef-

Applying UTAUT Model for an Acceptance Study Alluding the Use of Augmented Reality in Archaeological Sites

113

fort Expectancy (EE), Social Influence (SI), and Fa-

cilitating Conditions (FC). The dependent variable

(DV) is Behavioural Intention (BI). For each vari-

able several items in the questionnaire were presented

through a Likert-type scale classifying the level of

agreement, from 1 - strongly disagree, to 7 - strongly

agree.

3.1.1 Performance Expectancy

Venkatesh et al. defined Performance Expectancy

(PE) as the degree to which a person believes that

using the system will help each individual to ob-

tain gains related to something. In the original

model, these gains were related to job performance

(Venkatesh et al., 2003).

The items used to evaluate PE in the current study

were the following:

PE.1 Using augmented reality may help me get

more information about the archaeological space.

PE.2 Using augmented reality may help me get

information about the archaeological space more

quickly.

PE.3 Using augmented reality may increase my

interest in archaeological spaces.

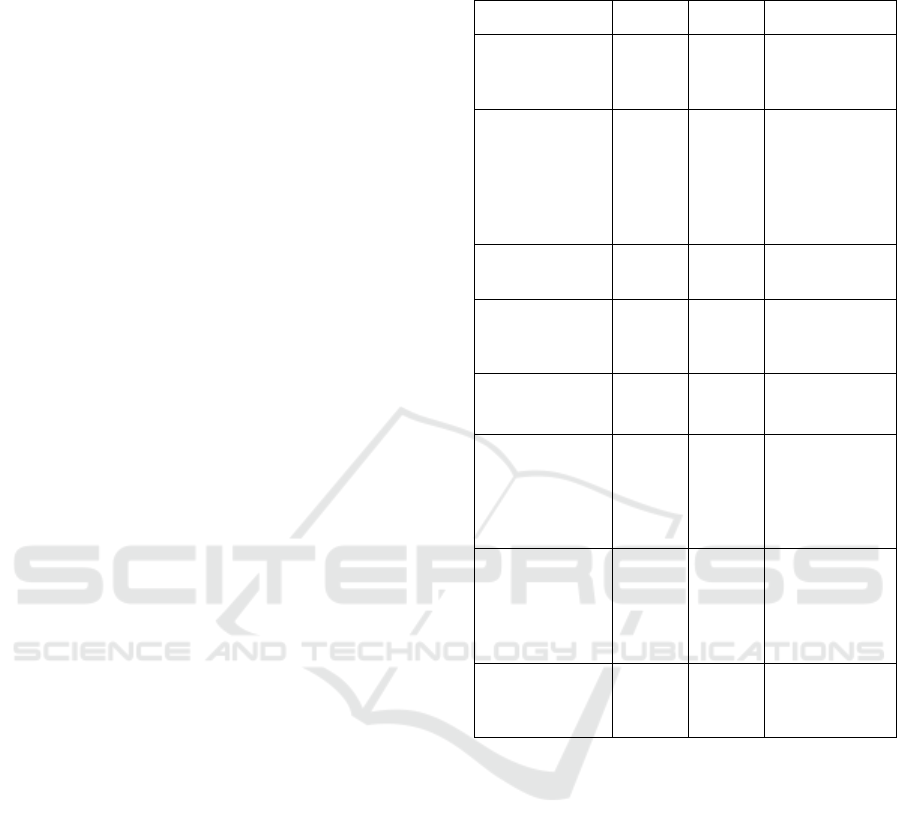

Figure 1: Graphic representation of the items used to eval-

uate performance expectancy for the current study.

Figure 1 summarizes the items used to evaluate

PE, specifically, quantity of information, quickness

of acquiring information, and enhancement of inter-

est for archaeological spaces.

3.1.2 Effort Expectancy

Venkatesh et al. defined Effort Expectancy (EE) as

the degree of ease associated with the use of the sys-

tem (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

The items used to evaluate EE in the current study

were the following:

EE.1 I think that augmented reality is easy to use.

EE.2 I think that my interaction with augmented

reality will be clear and understandable.

EE.3 It will be easy for me to become skilful at

using augmented reality.

Figure 2 summarizes the items used to evaluate

the independent variable EE, specifically, ease of use,

clearness of interaction, and ease to become skillful

in using AR.

Figure 2: Graphic representation of the items used to eval-

uate effort expectancy for the current study.

3.1.3 Social Influence

Venkatesh et al. defined Social Influence (SI) as the

degree to which a person perceives that important oth-

ers believe each individual should use the new system

(Venkatesh et al., 2003).

The items used to evaluate SI in the current study

were the following:

SI.1 People that are important to me (e.g. family

and friends) think that I should use augmented reality.

SI.2 I am more likely to use augmented reality if

people that are important to me use it as well.

SI.3 I am more likely to use augmented reality if

people around me use it as well.

Figure 3: Graphic representation of the items used to eval-

uate social influence for the current study.

Figure 3 summarizes the items used to evaluate

the independent variable SI, specifically, opinion of

friends and family, influence of friends and family,

and influence of people around.

3.1.4 Facilitating Conditions

Venkatesh et al. defined Facilitating Conditions (FC)

as degree to which an individual believes that an or-

ganizational and technical infrastructure exists to sup-

port the use of the system (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

The items used to evaluate FC in the current study

were the following:

FC.1 I have the resources necessary to use aug-

mented reality (e.g. smartphone).

FC.2 I have the necessary knowledge to use aug-

mented reality.

FC.3 Augmented reality is compatible with other

technologies I use.

FC.4 I can get help from others if I have difficul-

ties using augmented reality.

HUCAPP 2019 - 3rd International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

114

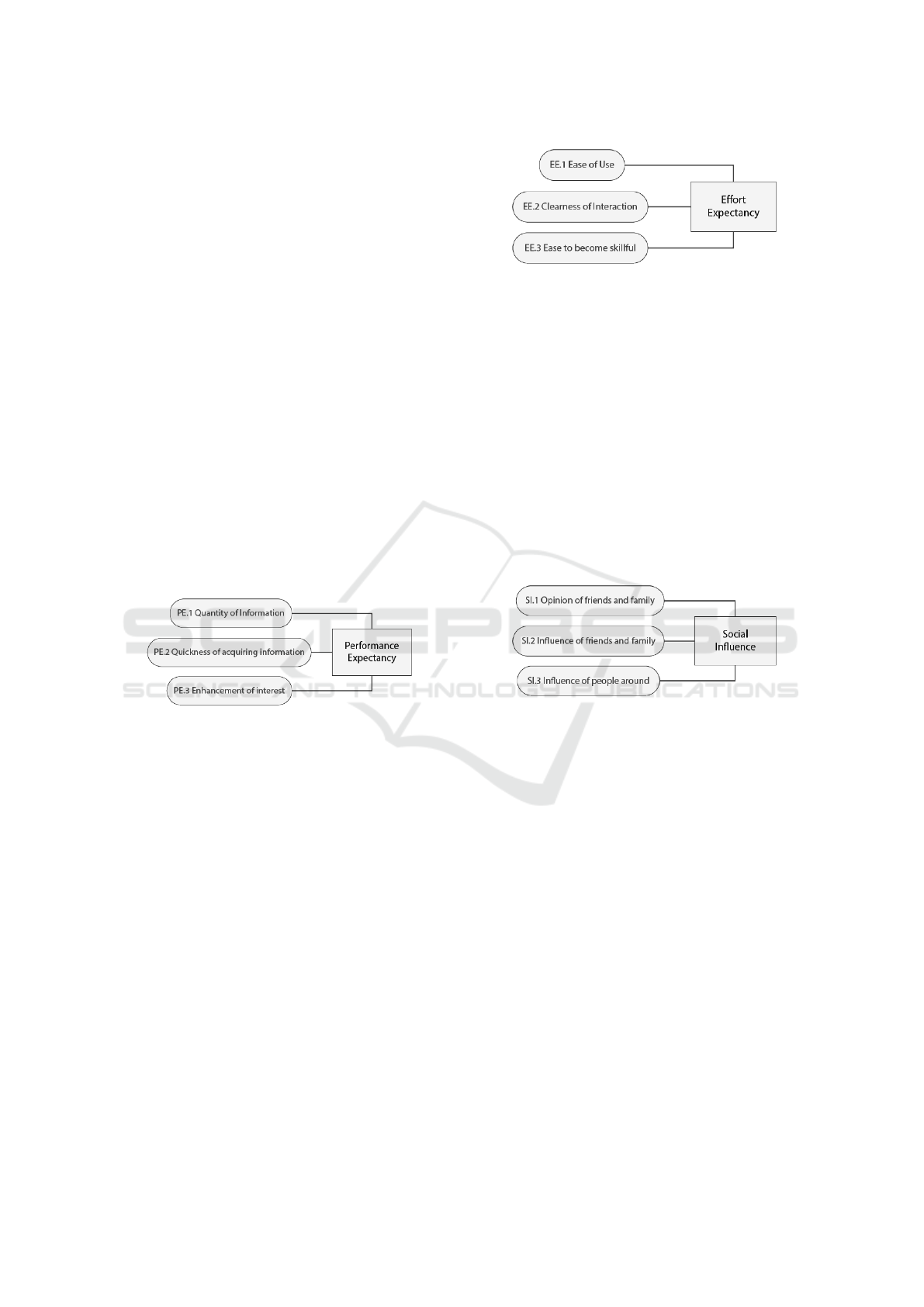

Figure 4: Graphic representation of the items used to eval-

uate facilitating conditions for the current study.

Figure 4 summarizes the items used to evaluate

the independent variable FC, specifically, adequacy of

resources to use AR technology, adequacy of knowl-

edge, compatibility with other technologies, and ade-

quacy of help available.

3.1.5 Behavioural Intention

According to Venkatesh et al., it is expected that Be-

havioural Intention (BI) will have a significant posi-

tive influence on technology usage (Venkatesh et al.,

2003).

The items used to evaluate this dependent variable

in the current study were the following:

BI.1 I would like to use augmented reality in ar-

chaeological spaces as soon as possible.

BI.2 I plan to use augmented reality applied to ar-

chaeological sites in the future.

BI.3 I will always try to use augmented reality

when visiting archaeological sites.

Figure 5: Graphic representation of the items used to eval-

uate behavioural intention for the current study.

Figure 5 summarizes the items used to evaluate

the independent variable BI, specifically, intention to

use as soon as possible, intention to use in future and,

intention to use it regularly.

3.2 Moderators

Regarding the UTAUT constructs, participants of the

current study, were asked to choose between male and

female options and to specify their age.

For this study, the stages of experience presented

in UTAUT original model, was converted Techno-

logical Knowledge. This moderator is evaluated by

each participant who classify themselves their level

of knowledge related to how to use augmented reality

through a 7 point Likert-scale, from 1 (very bad) to 7

(very good).

Voluntariness of Use was dropped because the use

of augmented reality in archaeological spaces is in-

tended to be an optional feature for visitors. Thus, it

is assumed that the voluntariness of use will be always

given state.

A new moderator was added considering the Ar-

chaeological Knowledge, which is evaluated by each

participant who classify themselves their level of

knowledge through a 7 point Likert-scale, from 1

(very bad) to 7 (very good).

3.3 Formulation of Hypothesis

The current study will use the hypothesis raised

in the unified theory presented by Venkatesh et al.

(Venkatesh et al., 2003), adapting the moderators to

the existing hypothesis. Thus, besides age and gender,

archaeological knowledge and technological knowl-

edge are considered in the following hypothesis:

PE.H1: The influence of performance expectancy

on behavioural intention will be moderated by age,

gender, archaeological knowledge and technological

knowledge, such that the effect will be stronger for

men, particularly for younger men, for higher archae-

ological connoisseurs and for higher technology con-

noisseurs.

Figure 6 illustrates this relation.

Figure 6: Graphic representation of the hypothesis PE.H1.

Regarding to effort expectancy, the hypothesis

raised by Venkatesh et al. (Venkatesh et al., 2003)

was tailored to the following:

EE.H2: The influence of effort expectancy on be-

havioural intention will be moderated by age, gender,

and technological knowledge, such that the effect will

be weaker for man, particularly younger man, and

particularly for higher technology connoisseurs.

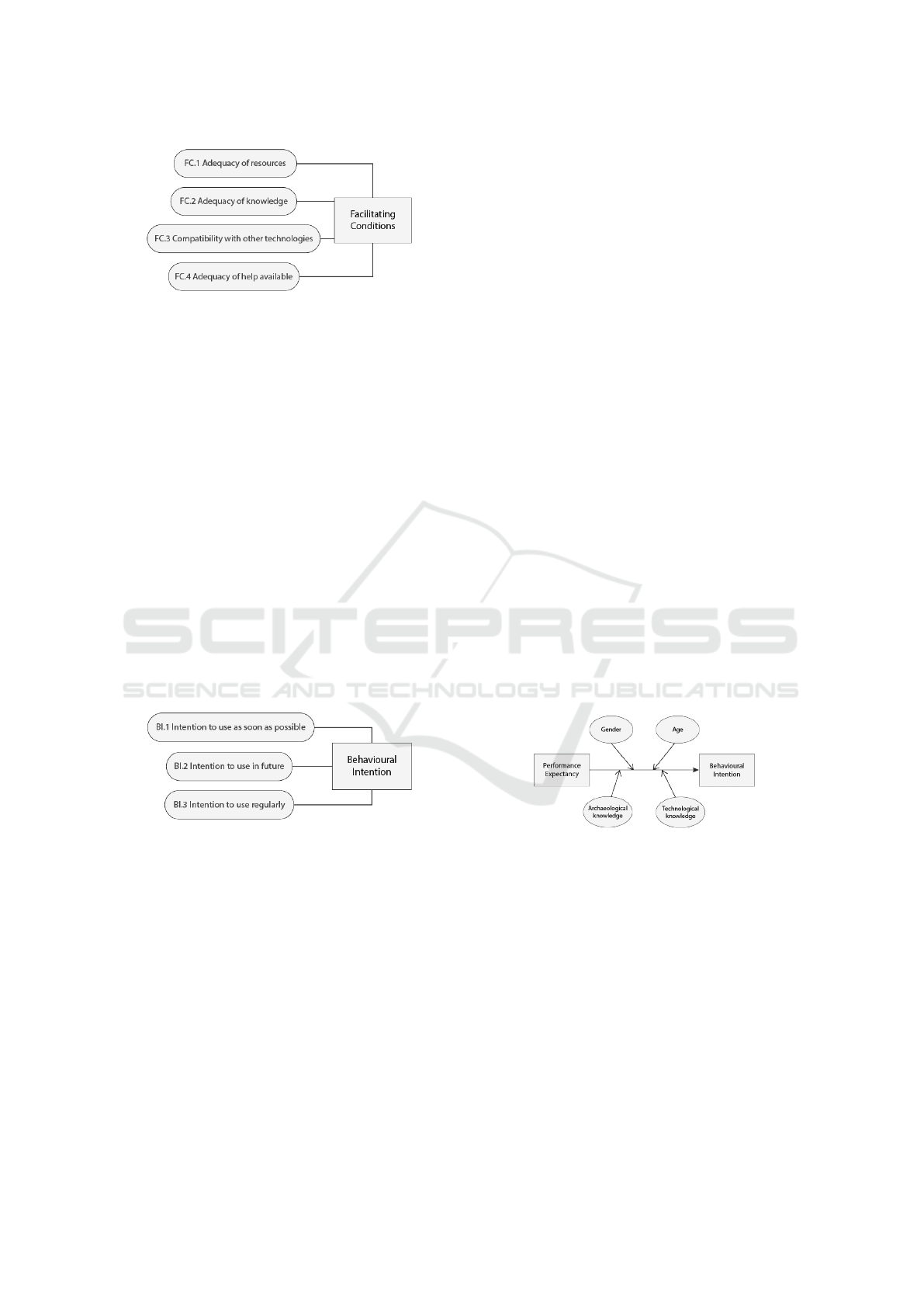

Figure 7 illustrates this relation.

Regarding to social influence, the literature sug-

gests that women tend to be more sensitive to others’

opinion, affecting their intention to use new technol-

ogy (Venkatesh, 2000). Accordingly, the on going hy-

pothesis is defined as follows:

Applying UTAUT Model for an Acceptance Study Alluding the Use of Augmented Reality in Archaeological Sites

115

Figure 7: Graphic representation of the hypothesis EE.H2.

SI.H3: The influence of social influence on be-

havioural intention will be moderated by age, gender,

and technological knowledge, such that the effect will

be stronger for women, particularly older women, and

particularly for lower technology connoisseurs.

Figure 8 illustrates this relation.

Figure 8: Graphic representation of the hypothesis SI.H3.

Regarding the facilitating conditions presented in

UTAUT model, where it was stated as an hypothesis

that FC will not have a significant influence on be-

havioural intention, for the current study a relation is

proposed, as it was updated in UTAUT2 (Venkatesh

et al., 2012) and as resulted as following.

FC.H4: The influence of facilitating conditions on

behavioural intention will be moderated by age, gen-

der and technological knowledge, such that the ef-

fect will be stronger for man, particularly younger

man, and particularly with high levels of technolog-

ical knowledge.

Figure 9 illustrates the relation created between

FC and the BI, considering the moderators age and

experience.

Figure 9: Graphic representation of the hypothesis FC.H4.

Considering the hypothesis raised in UTAUT2,

related to the impact of behavioural intention being

moderated by experience, this relation was adjusted

aiming to detect if age, gender, archaeological knowl-

edge and, technological knowledge would moderate

the behavioural intention to use AR technology. Ac-

cordingly, the hypothesis raised is the following:

BI.H5: The behavioural intention will be moder-

ated by age, gender, archaeological knowledge and

technological knowledge, such that the effect will be

stronger for men, particularly for younger men, for

higher archaeological connoisseurs, and for higher

technology connoisseurs.

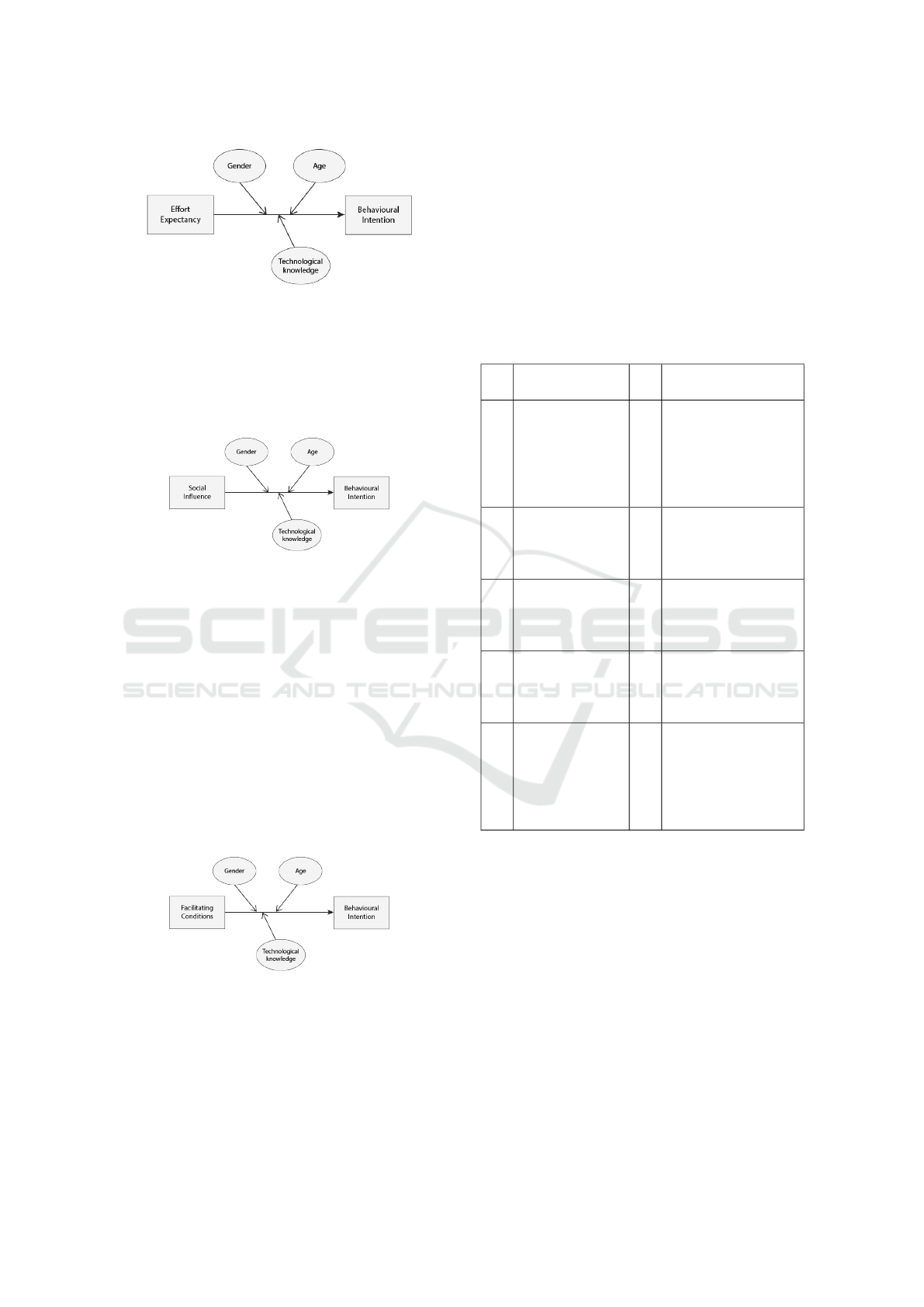

Table 2 resumes the relations created between

constructs and moderators, based on aforementioned

hypothesis.

Table 2: Summary of the hypothetical relations between

moderators and constructs.

IV Moderators DV

Hypothetical Sce-

nario

PE

Age, Gender,

Archaeological

knowledge,

Technological

knowledge

BI

Stronger for

younger men, with

higher levels of

archaeological

and technological

knowledge

EE

Age, Gender,

Technological

knowledge

BI

Weaker for younger

men with high

technological

knowledge

SI

Age, Gender,

Technological

knowledge

BI

Stronger for older

women with lower

technological

knowledge

FC

Age, Gender,

Technological

knowledge

BI

Stronger for

younger men with

high technological

knowledge

BI

Age, Gender,

Archaeological

knowledge,

Technological

knowledge,

Stronger for

younger men, with

higher levels of

archaeological

and technological

knowledge

4 RESULTS

A pre-test was carried out with a total of 31 answers

obtained in an archaeological space, in particular,

within the Roman Ruins of the Museu Monogr

´

afico

de Conimbriga-Museu Nacional (Portugal). Based on

participants feedback while answering the question-

naires, a time estimation to answer the entire ques-

tionnaire was stipulated, as well as, some adjustments

related to the reading interpretation of the questions

were made.

The current study collected a total of 166 partic-

ipants, whom answered an online questionnaire, be-

tween August and October 2018. The sample was

HUCAPP 2019 - 3rd International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

116

composed by 42.2% female and 57.8% male. Among

this heterogeneous group of participants, 61.7% of

them are between 17 and 30 years old, 22.2% are be-

tween 31 and 40 years old, 11.4% are between 41 and

50 years old, and 4.8% are more than 50 years old.

4.1 Correlations: Independent

Variables and the Behavioural

Intention Items

Correlations of Kendall’s coefficient between the dif-

ferent items which defines each construct were cre-

ated. These non parametric correlations are displayed

in the following tables.

The abbreviation ”C.C.” displayed thereafter

stands for Correlation Coefficient

1

, and ”Sig.” cor-

responds to Significance Test (2-tailed).

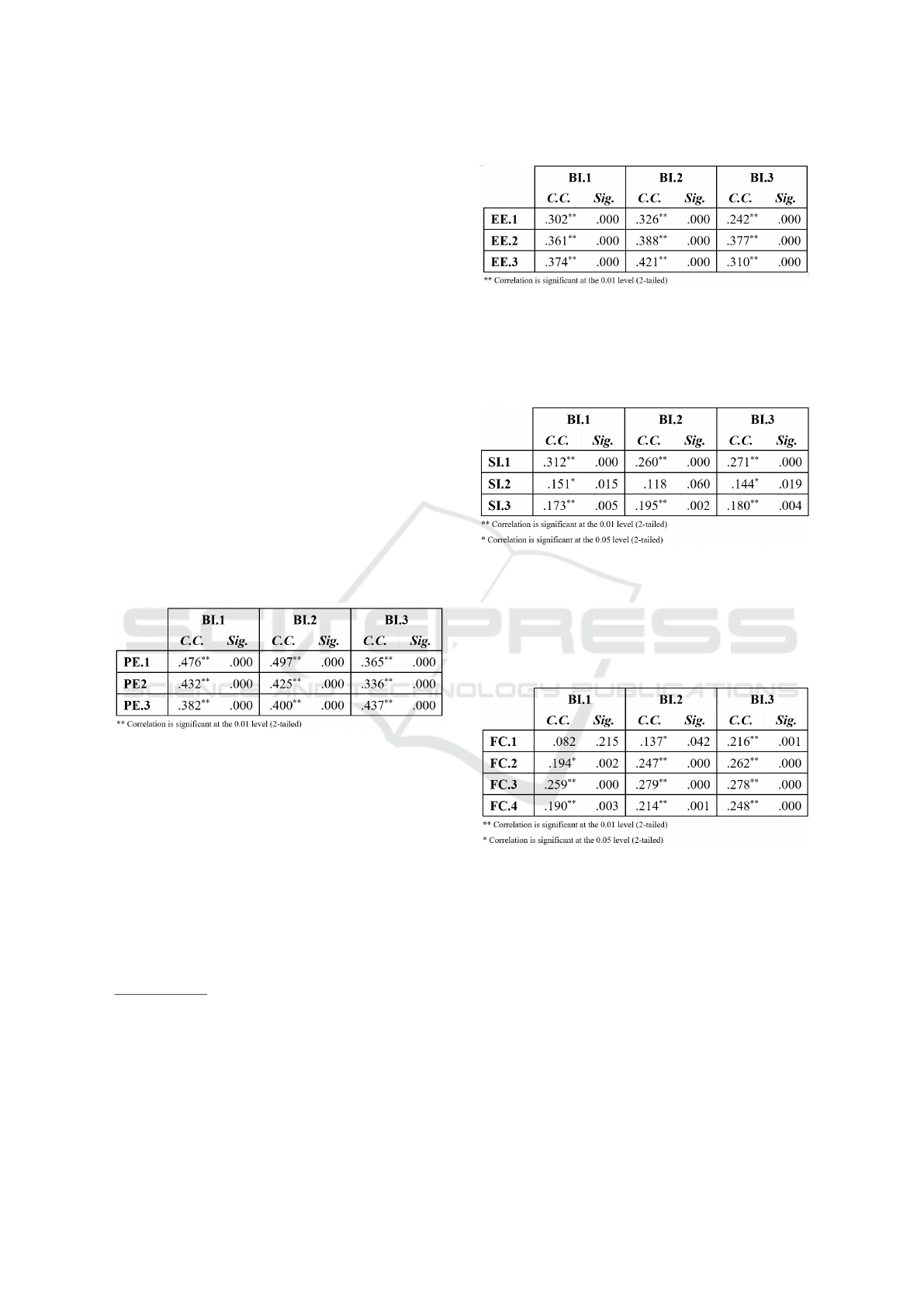

The correlations between PE items (IV) and BI

(DV) items, are shown in table 3. Table 4 displays the

correlations between EE items and BI items. Correla-

tions between SI and BI are visible in table 5, while

FC correlations with BI items are presented in table

6.

Table 3: Correlations found between PE and BI items.

Significant strong positive correlation were found

between PE and BI items (table 3). The stronger cor-

relation identified, with a coefficient of 0.497, was be-

tween Quantity of information (PE.1) and Intention to

use in future (BI.2), followed by other strong correla-

tions, such as between Quantity of information (PE.1)

and Intention to use as soon as possible (BI.1), and be-

tween Quickness of acquiring information (PE.2) and

Intention to use as soon as possible (BI.1).

Significant strong positive correlation were also

found between EE and BI items (table 4). The

stronger correlation identified, with a coefficient of

0.421, was between Ease to become skillful (EE.3)

1

Correlations measure the relationship between two

variables which can vary between -1 and 1. A zero value

means there is no correlation between those variables. The

closer a correlation is to 1 or -1, the stronger the relation-

ship is between variables. A negative correlation (closer to

-1) represents a stronger effect for the lower value. A posi-

tive correlation (closer to 1) represents a stronger effect for

the higher value).

Table 4: Correlations found between EE and BI items.

and Intention to use in future (BI.2), followed by

correlations between Clearness of Interaction (EE.2)

with both items: Intention to use as soon as possible

(BI.2), and Intention to use regularly (BI.3).

Table 5: Correlations found between SI and BI items.

Less significant strong positive correlation were

found between SI and BI items (table 5). The SI

item which appears to have strong correlations with

all three BI items is related with Opinion of friends

and family (SI.1).

Table 6: Correlations found between FC and BI items.

Despite less strong when compared with PE and

EE items, the correlations found between FC items

and BI are also significant strong and positive (ta-

ble 6). Stronger correlations disclosed with BI items

are related to Compatibility with other technologies

(FC.3).

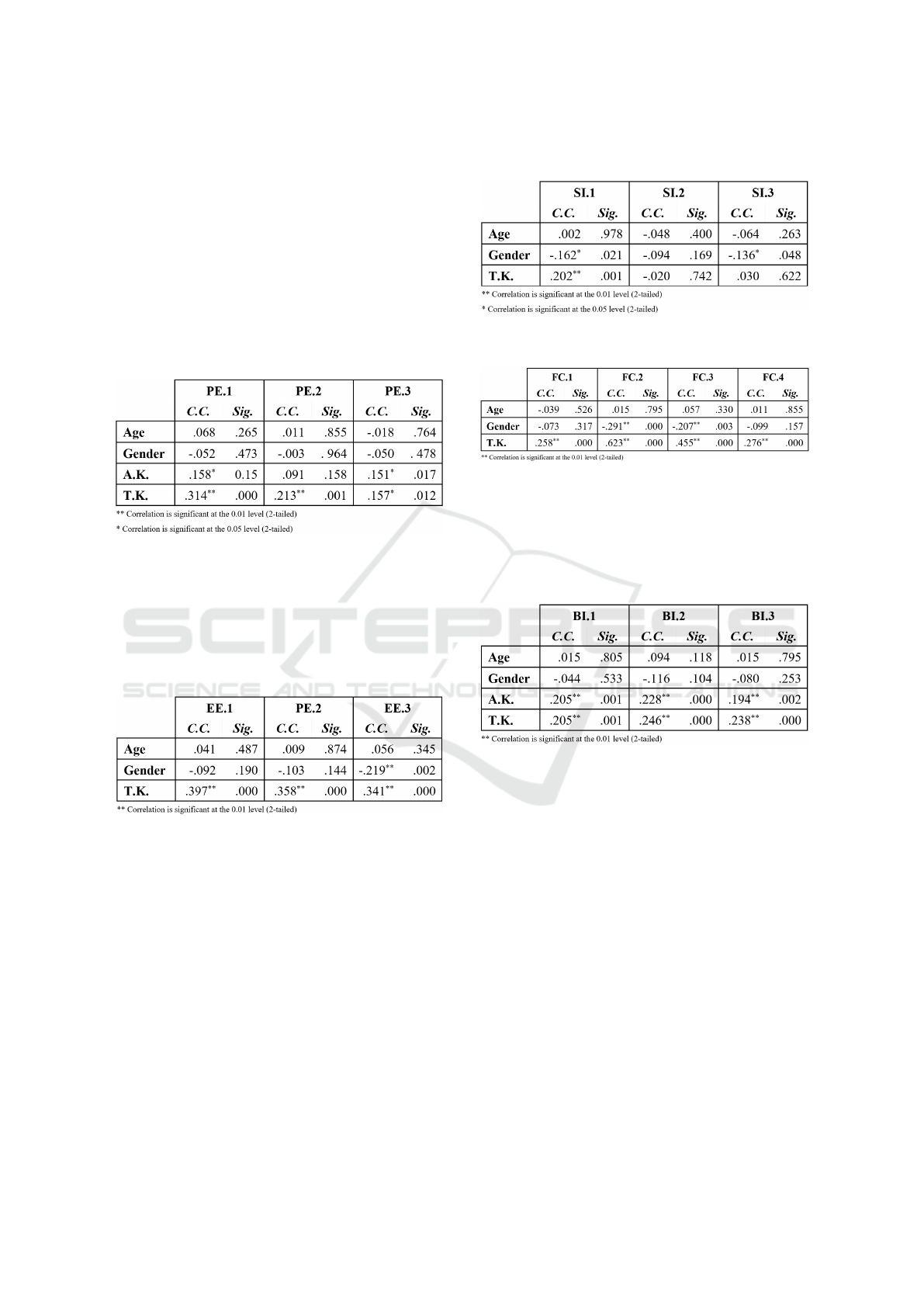

4.2 Correlations: Moderators and

Constructs

Regarding the aforementioned hypothesis, correla-

tions between moderators and PE items are shown

in table 7. Table 8 displays the correlations between

EE items and its moderators. Correlations between

Applying UTAUT Model for an Acceptance Study Alluding the Use of Augmented Reality in Archaeological Sites

117

SI and its moderators are visible in table 9, while FC

correlations with respective moderators items are pre-

sented in table 10. BI correlations with its moderators,

can be observed in table 11.

The abbreviation ”A.K.” displayed thereafter

stands for Archaeological Knowledge, and ”T.K.”

corresponds to Technological Knowledge. Regarding

gender analysis, to interpret these correlations, its al-

location is important to specify: value 1 was set for

males, and value 2 for females.

Table 7: Correlations found between moderators and PE

items.

No significant correlations were found regarding

to age and PE (table 7). Significant positive strong

correlations for archaeological knowledge and for

technological knowledge, were found being stronger

in this last moderator.

Table 8: Correlations found between moderators and EE

items.

No significant correlations were found regarding

to age and EE (table 8). A significant negative strong

correlation is found between gender and EE.3, reveal-

ing that this correlation is stronger for males. Sig-

nificant positive strong correlations for technological

knowledge for all EE items.

No significant correlations were found regarding

to age and SI items (table 9). A significant negative

strong correlation is found between gender and two

SI items (SI.1 and SI.2), revealing a stronger relation

among males. Technological knowledge has a signifi-

cant strong correlation with one SI item, namely, SI.1

(Opinion of friends and family).

No significant correlations were found regarding

to age and FC items (table 10). A significant nega-

tive strong correlation is found between gender and

Table 9: Correlations found between moderators and SI

items.

Table 10: Correlations found between moderators and FC

items.

FC.2, and FC.3, revealing a stronger relation among

males to these two items. Technological knowledge

has a significant positive strong correlation with all

FC items, notably for FC.2.

Table 11: Correlations found between moderators and BI

items.

No significant correlations were found regarding

to age neither to gender and BI items (table 11). Ar-

chaeological and technology knowledge are moder-

ators found to have significant positive correlations

with all BI items.

4.3 Bridging Results and Hypothesis

The given results revealed that the hypothesis are not

entirely true regarding the use of augmented technol-

ogy in archaeological sites.

Accordingly, in PE.H1, the influence of perfor-

mance expectancy on behavioural intention is not

moderated by gender neither by age, but is moder-

ated by archaeological knowledge and technological

knowledge, such that the effect is stronger for higher

archaeological connoisseurs, and for higher technol-

ogy connoisseurs.

Observing EE.H2, the presented results allow to

state that the influence of effort expectancy on be-

HUCAPP 2019 - 3rd International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

118

havioural intention is not moderated by age, but is

moderated by gender and by technological knowl-

edge, such that the effect is weaker for male, and par-

ticularly for higher technology connoisseurs.

Regarding to SI.H3, the collected data permit

to affirm that influence of social influence on be-

havioural intention is not moderated by age, but is

moderated by gender and by technological knowl-

edge, such that the effect is stronger for men, and par-

ticularly for lower technology connoisseurs.

From FC.H4, the presented results, allow to state

that the influence of facilitating conditions on be-

havioural intention is not moderated by age, but is

moderated by gender and technological knowledge,

such that the effect will be stronger for man, particu-

larly with high levels of technological knowledge.

While analysing BI.H5 hypothesis, it is possible

to state that behavioural intention is not moderated by

gender neither by age, but is moderated by archaeo-

logical knowledge and by technological knowledge,

such that the effect will be stronger for higher archae-

ological connoisseurs and, for higher technology con-

noisseurs.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The current study aimed to identify a suitable accep-

tance model for evaluating the behavioural intention

to use augmented reality technology in archaeologi-

cal spaces.

Hypothesis based on UTAUT model, with some

particular features covered in UTAUT2 model, and

some adjustments regarding the case study are pre-

sented. Moderators were also tested, dropping volun-

tariness of use, converting experience to technological

knowledge, and adding archaeological knowledge.

The results obtained, through online question-

naires, in a total of 166 valid answers for all questions,

revealed that the behavioural intention to use AR in

archaeological sites is influenced by performance ex-

pectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and fa-

cilitating conditions.

However, significant changes in the raised hypoth-

esis were observed regarding the moderators. The

collected data demonstrated that, for the use of AR in

archaeological sites, age does not play a role as mod-

erator to any construct analysed. Gender also missed

some relevance in some constructs, such as perfor-

mance expectancy and behavioural intention.

These findings confirm that 1) UTAUT model as a

suitable model for understanding the behavioural in-

tention to use AR, but also emphasize a second out-

come, 2) the importance of holding continuous accep-

tance studies to keep up-to-date new technologies un-

derstandings. Regarding the interest of implement-

ing this technology in archaeological spaces, a deeper

model should be applied to actual visitants, including

more constructs for wider understandings, as well as,

statistical studies regarding the prediction of results,

should also being accomplished.

Thus, this proposed model should be supple-

mented with more variables in order to better under-

stand the acceptance and intention to use a new tech-

nology, such as AR in archaeological sites. Despite

the fact that UTAUT model was shown as a suitable

model for understanding the behavioural intention to

use AR, it can be refined with the addition of variables

stemming from other models or/and theories. Accord-

ingly, a deepen research related to the integration of

new variables must be accomplished followed by a

new experimental evaluation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is financed by the ERDF – European Re-

gional Development Fund through the Operational

Programme for Competitiveness and Internationali-

sation - COMPETE 2020 Programme and by Na-

tional Funds through the Portuguese funding agency,

FCT - Fundac¸

˜

ao para a Ci

ˆ

encia e a Tecnologia within

project POCI-01-0145-FEDER-031309 entitled “Pro-

moTourVR - Promoting Tourism Destinations with

Multisensory Immersive Media.

REFERENCES

Ajzen, I. and Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes

and predicting social behaviour. Prentice-Hall.

Alqahtani, H. and Kavakli, M. (2018). A Theoretical

Model to Measure User’s Behavioural Intention to

Use iMAP-CampUS App. In 12th IEEE Conference

on Industrial Electronics and Applications (ICIEA),

pages 681–686, Siem Reap, Cambodia. IEEE.

Ashraf, A. R., Thongpapanl, N., and Auh, S. (2014). Accep-

tance Model Under Different Cultural Contexts: The

Case of Online Shopping Adoption. Journal of Inter-

national Marketing, 22(3):68–93.

Chung, N., Han, H., and Joun, Y. (2015). Tourists’ Intention

to Visit a Destination: The Role of Augmented Reality

(AR) Application for a Heritage Site. Computers in

Human Behavior, 50:588–599.

Davis, F. D. (1986). A Technology Acceptance Model for

Empirically Testing New End-User Systems: Theory

and Results. PhD thesis, MIT.

DeLone, W. H. and McLean, E. R. (1992). Information Sys-

tems Success: The Quest for the Dependent Variable.

Information Systems Research, 3(1):60–95.

Applying UTAUT Model for an Acceptance Study Alluding the Use of Augmented Reality in Archaeological Sites

119

DeLone, W. H. and McLean, E. R. (2003). The De-

Lone and McLean Model of Information Systems

Success. Journal of Management Information Sys-

tems, 19(4):9–30.

Escobar-Rodr

´

ıguez, T. and Carvajal-Trujillo, E. (2014). On-

line purchasing tickets for low cost carriers: An appli-

cation of the unified theory of acceptance and use of

technology (UTAUT) model. Tourism Management

journal, 43:70–88.

Fishbein, M. (1979). A theory of reasoned action: Some

applications and implications.

Goodhue, D. L. (1995). Understanding User Evalua-

tions of Information Systems. Management Science,

41(12):1827–1844.

Goodhue, D. L., Thompson, R. L., and Goodhue, B. D. L.

(1995). Task-Technology Fit and Individual Perfor-

mance. Mis Quarterly, 19(2):213–236.

Haugstvedt, A.-C. and Krogstie, J. (2012). Mobile Aug-

mented Reality for Cultural Heritage: A Technology

Acceptance Study. In Proceedings of the IEEE Inter-

national Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality

(ISMAR), pages 247–255, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Huang, T.-L. and Liao, S. (2015). A model of Acceptance of

Augmented-Reality Interactive Technology: the Mod-

erating Role of Cognitive Innovativeness. Electronic

Commerce Research, 15(2):269–295.

Ib

´

a

˜

nez, M.-B., Serio,

´

A. D., Villar

´

an, D., and Delgado-

Kloos, C. (2016). The Acceptance of Learning Aug-

mented Reality Environments: A Case Study. In Pro-

ceedings of the 16th International Conference on Ad-

vanced Learning Technologies (ICALT), pages 307–

311.

Jung, T., Chung, N., and Leue, M. C. (2015). The Determi-

nants of Recommendations to Use Augmented Real-

ity Technologies: The Case of a Korean Theme Park.

Tourism Management, 49:75–86.

Kourouthanassis, P., Boletsis, C., Bardaki, C., and

Chasanidou, D. (2015). Tourists Responses to Mo-

bile Augmented Reality Travel Guides: The Role of

Emotions on Adoption Behavior. Pervasive and Mo-

bile Computing, 18:71–87.

Shang, L. W., Siang, T. G., bin Zakaria, M. H., and Emran,

M. H. (2017). Mobile augmented reality applications

for heritage preservation in UNESCO world heritage

sites through adopting the UTAUT model. In Proceed-

ings of the AIP Conference, volume 1830. American

Institute of Physics Articles.

Shen, C.-w., Ho, J.-t., and Kup, T.-C. (2017). Behavioral

Intention of Using Virtual Reality in Learning. In Pro-

ceedings of the International World Wide Web Confer-

ence Committee, pages 129–137. Creative Commons

CC.

Tam, C. and Oliveira, T. (2017). Understanding mo-

bile banking individual performance: The DeLone &

McLean model and the moderating effects of individ-

ual culture. Internet Research, 27(3):538–562.

Tarhini, A., Hone, K., and Liu, X. (2015). A Cross-cultural

Examination of the Impact of Social, Organisational

and Individual Factors on Educational Technology

Acceptance Between British and Lebanese University

Students. British Journal of Educational Technology,

46(4):739–755.

tom Dieck, M. C. and Jung, T. (2018). A theoretical model

of mobile augmented reality acceptance in urban her-

itage tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(2):154–

174.

Usoro, A., Shoyelu, S., and Kuofie, M. (2010). Task-

Technology Fit and Technology Acceptance Models

Applicability to e-Tourism. Journal of Economic De-

velopment, Management, IT, Finance and Marketing,

2(1):1–32.

Venkatesh, V. (2000). Determinants of Perceived Ease of

Use: Integrating Control, Intrinsic Motivation, and

Emotion into the Technology Acceptance Model. In-

formation System Research, 11(4):342–365.

Venkatesh, V. and Bala, H. (2008). Technology Acceptance

Model 3 and a Research Agenda on Interventions. De-

cision Sciences, 39(2):273–315.

Venkatesh, V. and Davis, F. D. (2000). A Theoretical Ex-

tension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four

Longitudinal Field Studies. 46(2):186–204.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., and Davis, F. D.

(2003). User Acceptance of Information Technology:

Toward a Unified View. MIS Quarterly, 27:425–478.

Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y. L., and Xu, X. (2012). Con-

sumer Aceptance and Use of Information Technology:

Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use

of Technology. MIS Quarterly, 36(1):157–178.

Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y. L., and Xu, X. (2016). Unified

Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology: A Syn-

thesis and the Road Ahead. Journal of the Association

for Information Systems, 17(5):328–376.

HUCAPP 2019 - 3rd International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

120