Clinical Caremap Development: How Can Caremaps Standardise

Care When They Are Not Standardised?

Scott McLachlan

1,2

, Evangelia Kyrimi

2

, Kudakwashe Dube

1,3

and Norman Fenton

2

1

Health Informatics and Knowledge Engineering Research Group (HiKER), New Zealand

2

Risk and Information Management, Queen Mary University of London, London, U.K.

3

School of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand

Keywords: Caremap, Care Map, Clinical Documentation, Clinical Careflow, Flow Diagrams.

Abstract: Caremaps were developed to standardise care. They have evolved from text-based descriptions to flow-based

diagrams. Standardising care is seen to improve patient safety and outcomes, and to reduce the costs of

providing healthcare services, but contemporary caremaps are not standardised. This research investigates

contemporary caremaps and proposes a standardised model for caremap content, structure and development.

The proposed model is evaluated through two case studies to create caremaps for; 1) obstetric care during

labour and birth, and; 2) management and for women with gestational diabetes mellitus, finding that it is an

effective method for creating standardise caremaps.

1 INTRODUCTION

Caremap is a term currently used to describe a

graphical representation of the sequence of patient

care activities to be performed for a specific medical

condition. Caremaps have existed in some form for

around forty years (Hampton, 1993; Zander, 2002;

Gemmel et al., 2008). The literature suggests they

originated in the nursing domain, incorporating and

extending the critical pathway method and bringing

established project management methodologies into

healthcare delivery (Chu and Cesnik, 1998);

(Gemmel et al., 2008); (Zander, 1992). Caremaps are

intended to standardise health services by organising

and sequencing care delivery, ensuring a standard of

care and timely outcomes using an appropriate level

of resources (Marr and Reid, 1992; Hampton, 1993;

Blegen et al., 1995; Bumgarner and Evans, 1999).

The caremap can also help track variance in clinical

practice, as it provides a simple and effective visual

method for identifying when treatment or patient

outcomes have deviated from the routine evidence-

based pathway (Marr and Reid, 1992), (Houltram and

Scanlan, 2004).

Terminological disagreement persists as to

whether caremaps are a separate format of clinical

tool (Zander, 1992; Kehlet, 2011; Solsky et al., 2016),

or simply another name for care pathways, clinical

pathways, critical pathways and care plans (Holocek

and Sellards, 1997; Campbell et al., 1998; O'Neill and

Dluhy, 2000; Li et al., 2014). This terminology

confusion is further exemplified when we observe

flow diagrams that internally describe themselves as

a “care map”, yet are captioned ‘clinical pathway’ by

the author such as observed in Figure 1 of (Thompson

et al., 2011) and Figure 5 on p45 of (Yazbeck, 2014).

Yazbeck (2014) goes on to present a range of similar

flow diagrams for care management, describing them

using a range of titles including ‘care map’, ‘care

pathway’, and ‘algorithm’.

Nursing caremaps from the early 1990’s

contained considerably more text than their

contemporary counterparts, and were presented as the

sum of two components: (1) identifying patient

problems and necessary outcomes within a time-

frame which are (2) broken down and described day-

by-day as tasks on a critical path, (Marr and Reid,

1992; Ogilvie-Harris et al., 1993). Later approaches

presented three components: (1) the flow chart

diagram; (2) the transitional text-based care map of

activities broken down day-to-day, and; (3) the

evidence base relied upon in their construction

(Houltram and Scanlan, 2004). It is these approaches

which may have resulted in the terminology

confusion that persists to today.

More recent caremaps have tended towards

representation as a flow diagram made up of clinical

McLachlan, S., Kyrimi, E., Dube, K. and Fenton, N.

Clinical Caremap Development: How Can Caremaps Standardise Care When They Are Not Standardised?.

DOI: 10.5220/0007522601230134

In Proceedings of the 12th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2019), pages 123-134

ISBN: 978-989-758-353-7

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

123

options for a particular condition and resulting in

multiple possible paths based on: (i)

symptomatology; (ii) diagnostic results, and; (iii)

how the patient responds to treatment (Chan et al.,

2005; BCCancer, 2012; deForest and Thompson,

2012). Caremap examples can be found in many

healthcare domains, including: paediatric surgery

(Chan et al., 2005), nursing (deForest and Thompson,

2012), oncology (BCCancer, 2012), diagnostic

imaging (WAHealth, 2013), obstetrics (Comreid,

1996) and cardiology (Hampton, 1993). Even within

these examples there exists significant variance in

complexity level, design approach, content and the

representational structures used. There is currently no

standardised method for the development or

presentation of a clinical caremap (Bumgarner and

Evans, 1999). Changes in format between like

documents and poorly designed materials increase

ambiguity and create confusion for the clinician

(Hubner et al., 2010), (Valenstein, 2008), (Wang et

al., 2013). Standardised approaches to documentation

ensure that each time a clinician approaches that type

of document, the content and format meet their

expectations, can be read quicker, are better retained,

and improves patient safety and outcomes (Christian

et al., 2006; Valenstein, 2008). For this reason our

paper asks: how can caremaps be an effective tool to

standardise healthcare when caremaps themselves are

not standardised?

The rest of this paper is organised as follows:

Section 2 discusses caremap terminology, history and

evolution. Section 3 defines the problem of

standardisation and Section 4 reviews related

literature. Section 5 presents the methodology and

results of a literature review on the primary elements

of caremaps. The proposed standardised caremap

model is described in Sections 6 and 7 and validated

in Section 8 through the conduct of two case studies

in the area of midwifery and obstetrics. The paper is

then summarised and concludes with proposals for

future work.

2 CAREMAPS: TERMS,

BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT

2.1 Caremap Terminology

Definitions drawn from literature of the early-mid

1990’s agree in principle that the caremap presents as

a graph or schedule of care activities described on a

timeline and performed as part of the patient’s

treatment by a multidisciplinary team to produce

identified outcomes (Marr and Reid, 1992; Hampton,

1993; Ogilvie-Harris et al., 1993; Blegen et al., 1995;

Wilson, 1995; Gordon, 1996; Hill, 1998; Zander,

2002). While the format of caremaps has changed

over the intervening decades, this general definition

is still appropriate.

Caremaps are observed under three different

titles: caremaps, CareMaps and care maps. The first

appears to have been the original title prior to the

Centre for Case Management (CCM) trademarking

CareMaps in the early 1990’s (Blegen et al., 1995;

Dickinson et al., 2000). In literature published after

1994 that uses caremaps, it is not uncommon to see

some mention of CCM or their trademark (Philie,

2001), although some don’t (Griffith et al., 1996;

Saint-Jacques et al., 2005). The use of care maps has

possibly come as a defence to any potential issues that

might have arisen from confusion with the trademark,

as we did not see authors using this third type in

context or with reference to CCM (Marr and Reid,

1992; Mackay et al., 2007; Royall et al., 2014).

2.2 Background of Caremaps

While there appear to be three descriptions for the

origin of caremaps, there are points of intersection

between each. The descriptions are:

(1) That caremaps resulted as an output of the CCM

in 1991 (Dickinson et al., 2000). CCM’s

CareMaps were similar in form and function to

existing clinical pathways and were applied to

specific patient populations that were commonly

treated in high numbers in hospitals (Dickinson et

al., 2000). This organisation then went on to

trademark the double-capitalised version

CareMap but had not within the first decade

undertaken any research to demonstrate

effectiveness of the concept whose invention they

claimed (Jones and Norman, 1998).

(2) That caremaps naturally evolved as an expansion

of earlier case management and care plans

(Zander, 2002).

(3) That caremaps were developed during the 1980’s

at the New England Medical Centre (NEMC)

(Wilson, 1995; Schwoebel, 1998).

There is some support for the notion that caremaps

had existed in the decade before the CCM’s

‘invention’ and trademark, in that it had been

observed that nurses were the primary users of

caremaps in the 1989 (Etheredge, 1989; Wilson,

1995).

Where the intersection occurs is: (a) between the

first two descriptions and in the way that staff of

HEALTHINF 2019 - 12th International Conference on Health Informatics

124

CCM have sought to elevate differences between

clinical pathways and their model of CareMaps;

identifying that the former represented a first-

generation concept while the latter improves on it by

adding consideration of variance and outcome

measurement (Morreale, 1997), and; (b) between the

last two in that each has some element in their story

suggesting caremaps came into existence in the

1980’s.

2.3 Caremap Evolution and Current

Context

Early caremaps were text-based and holistic. Rather

than focusing on just the immediate primary

diagnosis or intervention, nurses developed them to

focus on the entire scope of care that might be

necessary for the patient during their hospitalisation

event. These traditional caremaps considered

elements such as anxiety, rehabilitation, education,

prevention and coping strategies and were intended to

restore the patient to a normal quality of life (Marr

and Reid, 1992; Goode and Blegen, 1993; Ogilvie-

Harris et al., 1993; Wilson, 1995; Feigin, 1996).

In the second half of the 1990’s care providers

began to identify that creating caremaps was easier

for surgical procedures than other in-hospital care

intervention situations (DeJesse et al., 1995).

Evolution of caremaps in form and function was

expected as information technology and evidence-

based medicine developed (Wilson, 1995). Starting

from 1999 there began to be examples of transitional

caremaps; caremaps that whilst still being text-based,

have reduced their focus to interventions limited to

the primary diagnosis (Bumgarner and Evans, 1999;

Cholock, 2001; Philie, 2001).

As caremaps evolved into graphical

representations we begin to find contemporary

caremaps presented as a separate but complementary

component to the clinical pathway or clinical practice

guideline (Dickinson et al., 2000); (Saint-Jacques et

al., 2005). More recent caremaps are linked to or

provide a graphical flow representation for a clinical

practice guideline (CPG) or surgical event (Houltram

and Scanlan, 2004; Chan et al., 2005; Royall et al.,

2014). While retaining the purpose and flow, many of

those seen today annexed to CPGs have even dropped

the title (RWH, 2010; TCHaW, 2010; Thompson et

al., 2013; Reading et al., 2015). A summary of the

relevant elements of each caremap type is included in

Table 1.

3 THE PROBLEM:

STANDARDISING THE

CAREMAP AND ITS

DEVELOPMENT PROCESS

Proponents see standardisation of care processes as an

effective method for reducing healthcare service

delivery costs and variation, while increasing quality,

safety, efficacy and outcomes, improving the patient

experience and overall quality of life (Appleby et al.,

2011; Zarzuela et al., 2015). Yet we see that

healthcare remains one of the slowest industries to

adopt process standardisation or to demonstrate it has

positive impacts on patient safety and outcomes

(Leotsakos et al., 2014; Zarzuela et al., 2015; Binks,

2017). This in part is due to clinician resistance; with

attempts at care standardisation derided as

‘cookbook’ or ‘cookie cutter medicine’ that some say

Table 1: Summary and Comparison of Caremap Evolution Stages.

Traditional

(1980’s to mid-1990’s) *

Transitional

(Mid-1990’s to mid 2000’s) *

Contemporary

(2004 onwards) *

Primary Author Nurses Nurses and Doctors Doctors

Context Holistic Primary condition

Single diagnostic, screening and/or

intervention event.

Foci

Restoring the patient to

normal life

Outcomes, cost and resource consumption

Efficiency of care delivery and outcomes,

reduction of practice variation, bridge gap

between evidence and practice

Presentation Tex

t

-

b

ased Tex

t

-

b

ased with some early flow examples Flow diagram or graph

Status Independent document

Independent or sometimes incorporated

with CP document

Self-contained but often found appended

to/contained in CPG

CP = Clinical Pathway, CPG = Clinical Practice Guide

*All dates are approximate ranges

Clinical Caremap Development: How Can Caremaps Standardise Care When They Are Not Standardised?

125

can only be effective after they have set aside the

unique needs of individual patients (Giffin and Giffin,

1994; Rotter et al., 2008; Zarzuela et al., 2015;

Corbett, 2016). Given the current overuse issues and

financial crisis pervading healthcare service delivery

globally, standardisation of key documentation can

help clinicians deliver managed care, which is seen to

reduce incidences of inappropriate and ineffective

care, resource consumption and overall cost (Keyhani

et al., 2014; Martin, 2014).

Caremaps, clinical and critical pathways, clinical

flow diagrams and nursing care plans are observed

with vastly different content and appearance within

the same journal, from hospital to hospital, and

sometimes even from ward to ward in the same

hospital. While much literature presents caremaps

and other clinical documents such as clinical

pathways, and texts exist for the development of

traditional text-based caremaps, a gap exists with

regards to presenting a standard for the development

and structure of contemporary caremaps. This

research seeks to differentiate contemporary

caremaps from other forms of clinical documentation,

and to present one possible solution to standardising

their development, structure and content.

4 RELATED WORKS

There were numerous examples of contemporary

caremaps in the literature and annexed to hospital-

based clinical practice guidelines (CPGs).

Contemporary caremap literature tended to focus on

establishing the clinical condition that justified

creation of the caremap, such as: determination of

incidence, risk factors and patient outcomes (Chan et

al., 2005); diagnosis and stabilisation of patients with

an acute presentation (deForest and Thompson,

2012), and; protocolising of ongoing treatment

(Royall et al., 2014). Presentation or discussion of the

development process and elements for construction

were rare, and more often had to be inferred via a

thorough reading of each paper.

A single article was located that attempts to

describe a systematic process for contemporary

caremap development (Sackman and Citrin, 2014).

Authored by a veterinarian and a lawyer, this article

focuses more on standardising care process

representation into a clinical caremap for the purposes

of cost containment and provides the example of

mapping a surgical procedure (Sackman and Citrin,

2014). Given their focus and particular caremap

construction which, through their own exemplar

application only includes a temporally-ordered

single-path representation of the gross steps of patient

care, their paper might only be considered formative

at best. By their own admission they deliberately

limited the relevant data analysed during the input

design phase to only what is truly critical for

identifying and understanding outliers, which results

in its lack of clinical applicability and distinct lack of

detail surrounding each care process (Sackman and

Citrin, 2014). Their method requires significant work

to adequately support true standardised clinical

caremap development.

5 METHODOLOGY

Literature Review: A search using the terms

‘caremap’, ‘CareMap’, and ‘care map’ was conducted

across a range of databases. A citation search was also

performed on all included papers. This search yielded

1,747 papers. Once duplicates, papers not based in the

nursing, medical or healthcare domains and those

using the term “care map” in other contexts were

removed a core pool of 115 papers remained.

Development of Review Framework using Thematic

Analysis: Initially each paper was reviewed using

standard content and thematic analysis (Vaismoradi

et al., 2013) and concept analysis (Stumme, 2009) to

identify and classify terminology, construction and

content elements and infer development processes.

Methodology for Standardisation of Caremaps:

Literature reviews have a ground-level consensus

forming function allowing identification of

implementation techniques and the degree of accord

within a domain (Bero et al., 1998; Cook et al., 2013).

The literature pool was used to identify common

definition, structure and content elements of

caremaps. In addition, process steps that were

consistently described led us to a standardised

caremap development process.

Methodology for Evaluation of Proposed Standard

for Caremaps: Case Studies are a grounded

comparative research methodology with a well-

developed history, robust qualitative procedures and

process validation (McLachlan, 2017). The case

study approach provides a real-life perspective on

observed interactions and is regularly used in

information sciences (Lee, 1989; Cable, 1994;

Smithson, 1994; Peak et al., 2005). Case studies are

considered as developed and tested as any other

scientific method and are a valid method where more

rigid approaches to experimental research cannot or

do not apply (Eisenhardt, 1989; Tellis, 1997; Yin,

HEALTHINF 2019 - 12th International Conference on Health Informatics

126

2011). Both the standardised development process

and resulting caremap are evaluated using case

studies of examples from the author’s other works.

6 CONSENSUS FORMATION ON

CAREMAP: COMPOSITION

AND DEVELOPMENT PROCESS

The literature was used to establish consensus on

common structure, content and development

processes previously used in the creation of

caremaps, and which may be relevant in defining

standard caremap and development processes. The

case studies are used to evaluate and refine each. The

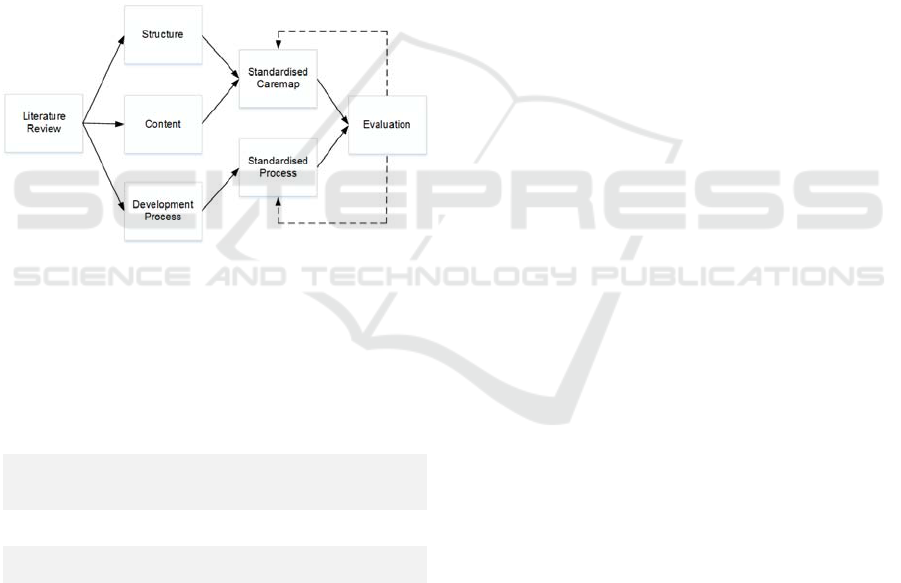

research was conducted following the overall

approach presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Research process – Consensus formation and

evaluation.

To address the stated aim of this paper, we

focused our research on tertiary care (hospital-borne)

caremaps and specifically the following three

components whose characteristics came out of the

thematic analysis and make up the review framework:

Structure

What is the representational structure and

notation for expressing contemporary

caremaps?

Content

What content types are consistently seen in

contemporary caremaps?

Development

What are the process steps followed for

developing contemporary caremaps?

6.1 Structure

As described in Table 1, caremaps have evolved from

wordy texts (Goode and Blegen, 1993; Gordon, 1996;

Holocek and Sellards, 1997; Bumgarner and Evans,

1999; Matula and Shollenberger, 1999; Philie, 2001)

to illustrative graphs (Chu and Cesnik, 1998;

Panzarasa et al., 2002; Houltram and Scanlan, 2004;

Li et al., 2014; Royall et al., 2014; Michelson et al.,

2018). Most contemporary caremaps present either as

monochromatic, i.e. black and white (Dickinson et

al., 2000; Chan et al., 2005; Ye et al., 2009;

Gopalakrishna et al., 2016) or full colour (Saint-

Jacques et al., 2005; Milne et al., 2013) flow

diagrams: a well-known process modelling tool

(Gilbreth and Gilbreth, 1921). Generally, each flow

diagram has its own boxes and notations, and the

most common is a rectangle that represents a process

step, usually called an activity. Contemporary

caremaps contain a set of activities representing

medical care processes. However, the literature

shows there is no consistency in the way that an

activity is represented. Different shapes such as

rectangular boxes with rounded (Thompson et al.,

2011) or square corners (Chu and Cesnik, 1998;

Panzarasa et al., 2002; Royall et al., 2014), plain text

(Dickinson et al., 2000), or even arrows

(Gopalakrishna et al., 2016) have been used. In some

cases, activities that lead to different mutually

exclusive pathways are presented by a diamond

(Panzarasa et al., 2002; Ye et al., 2009; van de

Klundert et al., 2010; Li et al., 2014). The flow from

one activity to another is illustrated with arrows

(Panzarasa et al., 2002; Houltram and Scanlan, 2004;

Chan et al., 2005; Milne et al., 2013), or simple lines

(Dickinson et al., 2000; Li et al., 2014). The literature

lacks a clear description as to whether a caremap

should have an entry and an exit point. In some cases

neither is present (Houltram and Scanlan, 2004;

Thompson et al., 2011; Royall et al., 2014), while in

others these points are an implicit (van de Klundert et

al., 2010; Li et al., 2014; Michelson et al., 2018) or

explicit part of the diagram (Panzarasa et al., 2002).

Finally, most of the reviewed caremaps contain

multiple pathways and they are often presented as

multi-level flow charts (Chu and Cesnik, 1998;

Panzarasa et al., 2002; Ye et al., 2009).

6.2 Content

Each activity in the caremap represents a specific

medical process. Diagnosis, treatment and ongoing

monitoring/evaluation are three medical activities

that are consistently observed (van de Klundert et al.,

2010; Thompson et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2012). It

is common for a caremap to contain a set of targeted

outcomes (Chu and Cesnik, 1998; Panzarasa et al.,

2002; Chan et al., 2005; Li et al., 2014; Royall et al.,

2014). Time, described either as a duration or inferred

from the step-by-step nature of the dynamic care

process, is often part of the caremap (Saint-Jacques et

al., 2005; Ye et al., 2009; van de Klundert et al., 2010;

Michelson et al., 2018). Finally, an explanation

Clinical Caremap Development: How Can Caremaps Standardise Care When They Are Not Standardised?

127

associated with the activities and/or arrows captured

in the caremap may be present (Houltram and

Scanlan, 2004; Chan et al., 2005; Saint-Jacques et al.,

2005), (Ye et al., 2009; Thompson et al., 2011; Milne

et al., 2013; Royall et al., 2014; Michelson et al.,

2018). The explanation helps to better describe an

activity or to justify the flow from one activity to

another.

6.3 Development Process

The development process of a contemporary caremap

is a subject that has gained significantly less attention

in the literature. Only 19 out of the 115 papers

provides any detail regarding the development

process. Of these only 6 describe the development

process with any deliberate nature or clarity (Giffin

and Giffin, 1994; Hydo, 1995; Thompson et al., 2011;

Huang et al., 2012; Lodewijckx et al, 2012). From the

rest, the steps to develop the caremap can only be

inferred (Hill, 1998; Dickinson et al., 2000; Panzarasa

et al., 2002; Royall et al., 2014).

7 TOWARDS

STANDARDISATION OF

CAREMAPS

7.1 Model for Standardised Caremap

Structure

Contemporary caremaps are presented as flow

diagrams. However, as described in Section 6.1 there

is neither a consistent caremap structure nor a good

representation of the elements included in a caremap.

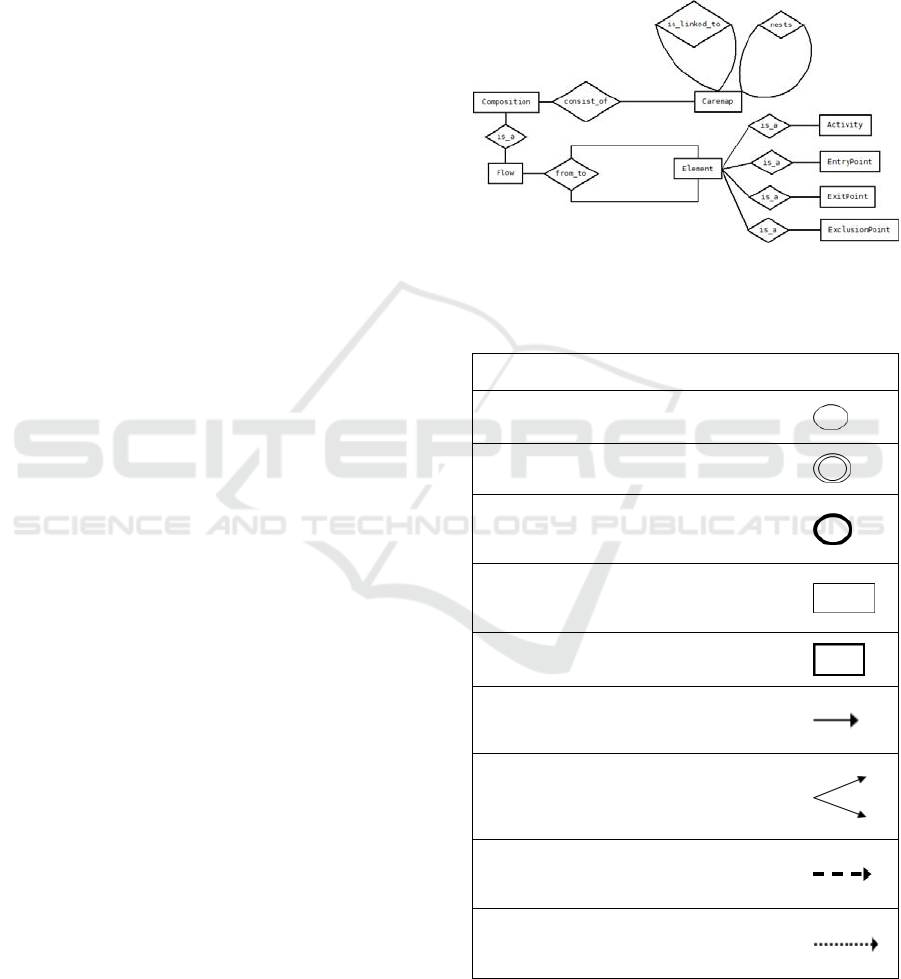

To resolve this problem an entity relationship model,

shown in Figure 2 that describes the relationship

among structural elements of a caremap,

demonstrated in Table 2, is proposed. The elements

are inspired by the standardised pictorial elements

seen in UML and hard state chart notations.

Following this, the standardised structural model of

the caremap is demonstrated in the content model

shown in Figure 3.

7.2 Model for Standardised Caremap

Content

The three main content types that were consistently

captured in the contemporary caremaps were

diagnosis, treatment and management/monitoring.

These are broad content types related to a set of

specific medical activities and data captured as shown

in Table 3. Following the structural model, an

exemplar content model is presented in Figure 3. The

three main content types represent different caremap

levels, while the described medical activities are the

components of that type of caremap. The proposed

standard content model represents the information

that should be captured in a caremap.

Figure 2: An Entity Relationship model for the caremap.

Table 2: Structural elements of caremaps and their

representational notation.

Element Descri

p

tion Notation

1

Entry

p

oint

Beginning of the caremap

2

Exit point End of the caremap

3

Exclusion

point

Exclusion from the caremap, as the

patient does not belong to the

tar

g

eted

p

o

p

ulation

4

Activity

A care or medical intervention that

is associated with a medical content

t

yp

e

(

see Table X in next section

)

5

Nested

Activity

An activity that has an underlying

caremap

6

Flow

Transition from one activity to

another

7

Multiple

pathways

Flow from an antecedent activity to

a number of successors from which

the clinician must choose the most

a

pp

ro

p

riate on

g

oin

g

p

ath

8

Nested

caremap

connection

Connection between an activity and

its nested caremap

9

Multi-level

caremap

connection

Connection between a series of

linked caremaps

HEALTHINF 2019 - 12th International Conference on Health Informatics

128

Figure 3: Content model for the caremap.

Table 3: Content type, activities and information captured

in caremap.

Content

Type

Activity

Data/Information

Captured

Diagnosis

Review patient records

Demographics

Medical histor

y

Collect patient history

Family history

Comorbidities

Ask personal, lifestyle

questions

Habits (risk factors)

Clinical examination

Signs

S

y

m

p

toms

Tar

g

eted exa

m

Dia

g

nostic test results

Disease assessment Dia

g

nosis

Treatment

Set

g

oals Ex

p

ected Outcomes

Consider different

interventions

Possible treatments

Consider potential

com

p

lications

Variances from expected

outcomes

Write prescription

Selected treatment

Treatment details

Monitoring

Review patient records

Previous test results

Previous s

y

m

p

toms

Clinical exa

m

Si

g

ns/S

y

m

p

toms

Tar

g

eted exa

m

Dia

g

nostic test results

Evaluate

g

oals Pro

g

ression

7.3 Model for Standardised Caremap

Development Process

Figure 4 presents the proposed development process

divided into six phases. During the initial phase the

conceptual framework should be decided, and a

multidisciplinary team assembled. The next phase

clarifies current practice and anticipated variance. A

review of available evidence is the final step prior to

production of the caremap. Once developed, it should

be evaluated and once agreed, implemented. As

Figure 4 shows, caremap development is a lifecycle

process. As new knowledge for the particular

condition or treatment or variance is identified, the

caremap should be reviewed (Huang et al., 2012).

Figure 4: Caremap development lifecycle.

Clinical Caremap Development: How Can Caremaps Standardise Care When They Are Not Standardised?

129

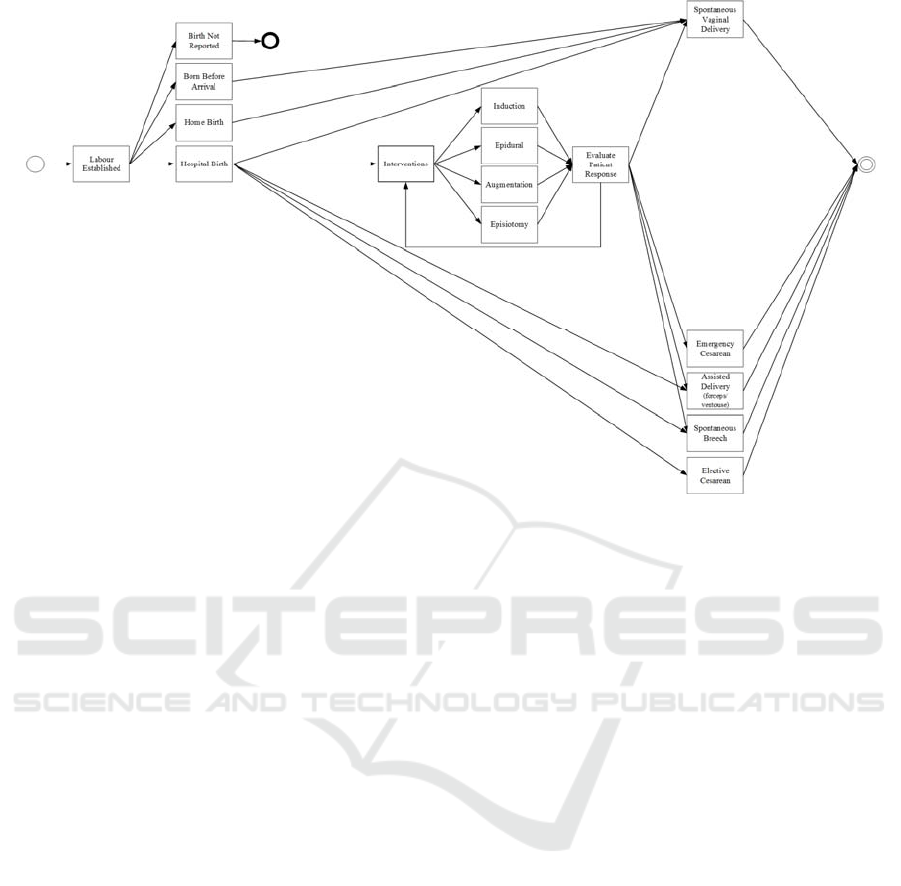

Figure 5: Labour and Birth Caremap.

8 EVALUATING THE

STANDARD

8.1 Study I: The Labour and Birth

Caremap

The labour and birth process represents an excellent

example for a first-pass evaluation case study to

assess the development process for caremaps. Labour

and birth has easily defined start and end points,

limited temporal variance, and a finite number of

easily identified treatment paths.

Inputs: Inputs for the labour and birth caremap were:

(a) clinical practice guidelines for intrapartum care at

Middlemore Hospital; (b) input and consensus of

midwives and obstetricians, and; (c) publicly

available incidence and treatment statistics from the

NZ Ministry of Health.

Development: An iterative development process

was used wherein the information scientist created an

initial version of the caremap based on the clinical

practice guideline (CPG) and evidence derived from

the treatment statistics. The initial caremap was

revised and refined during a number of sessions with

the clinicians. The resulting labour and birth caremap

for Middlemore Hospital is shown in Figure 5.

Validation: The Ministry of Health annually publish

Maternity and Newborn Data and Statistics for each

birthing unit and hospital. These statistics are

presented in the form of a contingency table whereby

the possible birthing outcomes and clinical

interventions are interrelated with a whole range of

demographic and clinical variables (maternal age at

birth, ethnicity, deprivation, maternal BMI and so

on). Using the 2014 release of these statistics, we

calculated the most likely treatment path that would

have been undertaken for all 8,731 birthing mothers

at one hospital unit. A state transition machine was

developed, digitised and realistic synthetic electronic

health records (RS-EHR) for all 8,731 women were

synthetically generated (McLachlan et al, 2016). The

treatment paths for each woman were digitally

compared against the caremap in Figure 5 to ensure a

valid path solution resolved for every recorded birth.

In this way we demonstrated that the caremap

represents the entire scope of patient presentations

and treatment options as performed by clinicians.

8.2 Study II: The Gestational Diabetes

Mellitus Management Caremap

As part of a project to design and build a population-

to-patient predictive learning health system (LHS) to

reduce clinical overuse and empower patients to

actively participate in their own care, Queen Mary

HEALTHINF 2019 - 12th International Conference on Health Informatics

130

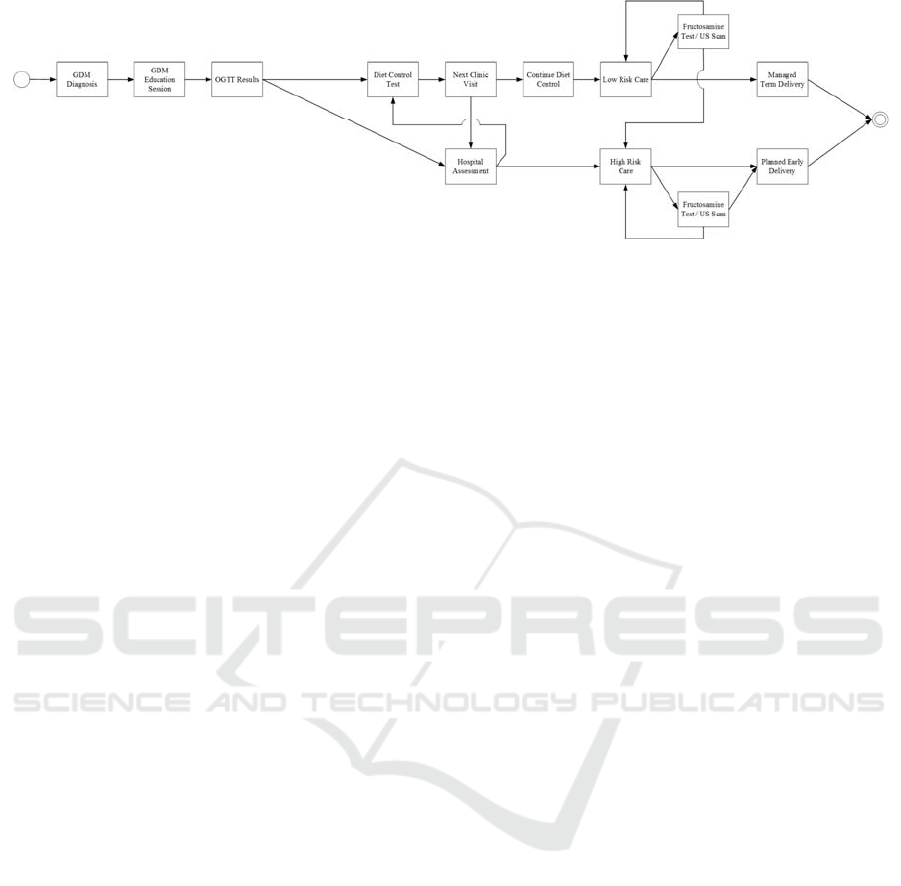

Figure 6: Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Management.

University of London’s PAMBAYESIAN project

(www.pambayesian.org) is creating a Bayesian

Network (BN) model (Fenton and Neil, 2018) to

predict treatment needs for individual mothers with

gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). The process

initially required creation of three caremaps, for (1)

diagnosis; (2) management, and; (3) postnatal follow

up.

Inputs: Inputs for the labour and birth caremap were:

(a) clinical practice guidelines for care of women with

diabetes in pregnancy, and; (b) input and consensus

from midwives and diabetologists.

Development: An iterative development process

was used wherein the decision scientist and

midwifery fellow worked together to deliver an initial

version of the caremap based on the clinical practice

guidelines (CPG) and clinical experience. The initial

caremap was revised and refined during a number of

sessions with the clinicians. Figure 6 presents the

resulting clinical management caremap for GDM.

Validation: Validation was performed through

consultation seeking consensus from three

diabetologists with tertiary care experience treating

obstetric patients under the CPGs used in the

caremaps’ creation.

9 SUMMARY AND

CONCLUSIONS

Some see standardising of care as limiting their

ability to make decisions based on the patient

presenting before them, creating ‘cookie-cutter

medicine’. However, caremaps are a form of

standardised clinical documentation that improve

patient safety and outcomes while still allowing

clinicians to select the most appropriate path for their

patient. Caremaps evolved during the last three

decades from primarily text-based approaches

developed by nurses, to flow-based visual aids

prepared by doctors as representations of clinical

screening, diagnosis and treatment processes. These

contemporary caremaps are presented in a variety of

ways and with differing levels of content.

Contemporary caremaps lack standardisation.

This paper presents one solution for standardising

caremap structure and content, and an approach for

caremap development distilled directly from analysis

of the entire pool of literature. The development

process was evaluated and refined during the

development of caremaps for case studies in

obstetrics and midwifery: (a) labour and birth, and (b)

management of patients with GDM. The resulting

caremaps were validated by expert consensus, with

the labour and birth caremap also being developed as

a state transition machine enabling rapid digital

validation against a dataset of synthetic patients.

If used consistently, the methods presented in this

paper will bring standardisation to caremaps and

ensure that, as clinical staff move between busy units

in a tertiary care setting, they are not distracted from

the patient in effort to understand the care flow

model. Every caremap would be familiar and time can

be given over to treating their patient, not trying to

understand the document.

Future work should address a standard approach

for identifying and representing the decision points

within a caremap, digital imputation of the caremap,

and representation of caremap logic in other

computer-aware and algorithmic forms, including

Bayesian Networks or Influence Diagrams (Fenton

and Neil 2018). These can form part of a learning

health system and provide population-to-patient level

prediction.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

SM, EK and NF acknowledge support from the

EPSRC under project EP/P009964/1:

Clinical Caremap Development: How Can Caremaps Standardise Care When They Are Not Standardised?

131

PAMBAYESIAN: Patient Managed decision-support

using Bayes Networks. KD acknowledges funding

and sponsorship for his research sabbatical at QMUL

from the School of Fundamental Sciences, Massey

University.

REFERENCES

Appleby, J., Raleigh, V., Frosini, F., Bevan, G., Gao, H., &

Lyscom, T. (2011). Variations in healthcare: The good,

the bad and the inexplicable. Report of The Kings

Fund.

BCCancer. (2012). Gallbladder: 3.Primary Surgical

Therapy. Sourced from: <http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/

books/gallbladder>.

Bero, L., Grilli, R., Grimshaw, J., Harvey, E., Oxman, A.,

& Thomson, M. (1998). Closing the gap between

research and practice: An overview of systematic

reviews of interventions to promote the implementation

of research findings. BMJ, 317(7156), 465-468.

Binks, C. (2017). Standardising the delivery of oral health

care practice in hospitals. Nursing Times, 113(11), 18-

21.

Blegen, M., Reiter, R., Goode, C., & Murphy, R. (1995).

Outcomes of hospital-based managed care: A

multivariate analysis of cost and quality. Managed

Care: Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 86(5), 809-814.

Bumgarner, S., & Evans, M. (1999). Clinical Care Map for

the ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy patient.

Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing, 14(1), 12-16.

Cable, G. (1994). Integrating case study and survey

research methods: An example in information systems.

European Journal of Information Systems, 3(2).

Campbell, H., Hotchkiss, R., Bradshaw, N., & Porteous, M.

(1998). Integrated care pathways. BMJ: British Medical

Journal, 316(7125), 133.

Chan, E., Russell, J., William, W., Arsdell, G., Coles, J., &

McCrindle, B. (2005). Postoperative chylothorax after

cardiothoracic surgery in children. Annals of Thoracic

Surgery, 80, 1864-1871.

Cholock, L. (2001). Caremap for the management of

asthma in a paediatric population in a primary

healthcare setting. Thesis in fulfilment of the degree of

Master of Nursing, University of Manitoba, Canada.

Christian, C., Gustafson, M., Roth, E., Sheridan, T.,

Gandhi, T., Dwyer, K., Dierks, M. (2006). A

prospective study of patient safety in the operating

room. Surgery, 139(2), 159-173.

Chu, S., & Cesnik, B. (1998). Improving clinical pathway

design: Lessons learned from a computerised prototype.

Int. Journal of Medical Informatics, 51, 1-11.

Comreid, L. (1996). Cost analysis: Initiation of HBMC and

first CareMap. Nursing Economics, 14(1), 34.

Cook, J., Nuccetelli, D., Green, S., Richardson, M.,

Winkler, B., Painting, R., Skuce, B. (2013).

Quantifying the consensus on anthropogenic global

warming in the scientific literature. Environmental

Research Letters, 8(2).

Corbett, E. (2016). Standardised care vs. Personalisation:

Can they coexist? (Quality & Process Improvement,

Health Catalyst ed.). Available at:

<https://www.healthcatalyst.com/standardized-care-

vs-personalization-can-they-coexist> [Access date:

November 14, 2018].

deForest, E., & Thompson, G. (2012). Advanced nursing

directives: Integrating validated clinical scoring

systems into nursing care in the pediatric emergency

department. Nursing Research and Practice.

DeJesse, P., Bland, C., Fuller, O., & Macbride, J. (1995).

Managed care… A view from the inside. Medical

Marketing and Media, 30(5).

Dickinson, C., Noud, M., Triggs, R., Turner, L., & Wilson,

S. (2000). The antenatal ward care delivery map: A

team model approach. Australian Health Review, 23(3),

68-76.

Eisenhardt, K. (1989). Building theories from case study

research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4).

Etheredge, M. (1989). Collaborative care, Nursing Case

Management. American Hospital: Chicago Illinois.

Feigin, J. (1996). Medical Care Management. Allergy and

Asthma Proc, 17(6), 359-361.

Fenton, N., & Neil, M. (2018). Risk Assessment and

Decision Analysis with Bayesian Networks, 2nd Ed.

London, UK: CRC Press.

Gemmel, P., Vandaele, D., & Tambeur, W. (2008).

Hospital Process Orientation (HPO): The development

of a measurement tool. Total Quality Management &

Business Excellence, 19(12), 1207-1217.

Giffin, M., & Giffin, R. (1994). Market memo: Critical

pathways produce tangible results. Health Care

Strategic Management, 12(7), 17-23.

Gilbreth, F., & Gilbreth, L. (1921). Process Charts.

American Society of Mechanical Engineers, ARK:

/13960/t57d3tx71.

Goode, C., & Blegen, M. (1993). Developing a CareMap

for patients with a cesarean birth: A multidisciplinary

process. Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing,

7(2), 40-49.

Gopalakrishna, G., Langendam, M., Scholten, R., Bossuyt,

P., & Leeflang, M. (2016). Defining the clinical

pathway in cochrane diagnostic test accuracy reviews.

BMC medical research methodology, 16(1), 153.

Gordon, D. (1996). Critical pathways: A road to

institutionalizing pain management. Journal of Pain

and Symptom Management, 11, 252-259.

Griffith, D., Hampton, D., Switzer, M., & Daniels, J.

(1996). Facilitating the recovery of open-heart surgery

patients through quality improvement efforts and

CareMAP implementation. American Journal of

Critical Care, 5(5), 346-352.

Hampton, D. (1993). Implementing a managed care

Framework through Care Maps. Journal of Nursing

Administration, 23(5), 21-27.

Hill. (1998). The development of care management systems

to achieve clinical integration. Advanced Practice

Nursing Quarterly, 4(1), 33.

Holocek, R., & Sellards, S. (1997). Use of a detailed clinical

pathway for Bone Marrow Transplant patients. Journal

HEALTHINF 2019 - 12th International Conference on Health Informatics

132

of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 14(4), 252-257.

Houltram, B., & Scanlan, M. (2004). Care maps: Atypical

antipsychotics. Nursing Standard, 18(36), 42-44.

Huang, B., Zhu, P., & Wu, C. (2012). Customer-Centered

Careflow Modeling Based on Guidelines. Journal of

Medical Systems, 36(5), 3307-3319.

Hubner, U., Flemming, D., Heitman, K., Oemig, F., Thun,

S., Diskerson, A., & Veenstra, M. (2010). The need for

standardised documents in continuity of care: Results

of standardising the eNursing summary. tudies in health

Technologies and Informatics, 160(2), 1169-1173.

Hydo, B. (1995). Designing an effective clinical pathway

for stroke. American Journal of Nursing, 95(3), 44-50.

Jones, A., & Norman, I. (1998). Managed mental health

care: Problems and possibilities. Journal of Psychiatric

and Mental Health Nursing, 5, 21-31.

Kehlet, H. (2011). Fast-track surgery: An update on

physiological care principles to enhance recovery.

Langenbeck’s Archives of Surgery, 396(5), 585-590.

Keyhani, S., Falk, R., Howell, E., Bishop, T., & Korenstein,

D. (2014). Overuse and systems of care: A systematic

review. Medical Care, 51(6).

Lee, A. (1989). A scientific method for MIS case studies.

MIS Quarterly, 33-50.

Leotsakos, A., Zheng, H., Croteau, R., Loeb, J., Sherman,

H., Hoffman, C., Munier, B. (2014). Standardisation in

patient safety: the WHO High 5’s project. Int. Journal

for Quality in Health Care, 26(2), 109-116.

Li, W., Liu, K., Yang, H., & Yu, C. (2014). Integrated

clinical pathway management for medical quality

improvement – based on a semiotically inspired

systems architecture. European Journal of Information

Systems, 23(4), 400-417.

Lodewijckx, C., Decramer, M., Sermeus, W., Panella, M.,

Deneckere, S., & Vanhaecht, K. (2012). Eight-step

method to build the clinical content of an evidence-

based care pathway: the case for COPD exacerbation.

Trials, 13, 229.

Mackay, D., Myles, M., Spooner, C., Lari, H., Typer, L.,

Blitz, S., Rowe, B. (2007). Changing the process of care

and practice in acute asthma in the emergency

department: Experience with an asthma care map in a

regional hospital. Canadian Journal of Emergency

Medicine, 9(5), 353-365.

Marr, J., & Reid, B. (1992). Implementing managed care

and case management: The neuroscience experience.

Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 24(5), 281-285.

Martin, E. (2014). Eliminating waste in healthcare. ASQ

Healthcare Update, 14.

Matula, P., & Shollenberger, D. (1999). Total joint project:

Acute care to home care. Med-Surg Nursing, 8(2), 92.

McLachlan, S. (2017). Realism in Synthetic Data

Generation. A thesis presented in fulfilment of the

requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy in

Science. School of engineering and Advanced

Technology, Massey University. Palmerston North,

New Zealand.

McLachlan, S., Dube, K., & Gallagher, T. (2016). Using the

Caremap with Incidence Statistics for Generating the

Realistic Synthetic Electronic Health Record.

Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference

on Health Informatics, ICHI’16.

Michelson, E., Huff, J., Loparo, M., Naunheim, R., Perron,

A., Rahm, M., . . . Berger, A. (2018). Emergency

Department Time Course for Mild Traumatic Brain

Injury Workup. he western journal of emergency

medicine, 19(4), 635-640.

Milne, T., Rogers, J., Kinnear, E., Martin, H., Lazzarini, P.,

Quinton, T., & Boyle, F. (2013). Developing an

evidence-based clinical pathway for the assessment,

diagnosis and management of acute Charcot Neuro-

Arthropathy: a systematic review. Journal of foot and

ankle research, 6(1), 30.

Morreale, M. (1997). Evaluation of a Care Map for

community-acquired pneumonia hospital patients.

Masters thesis. Queen’s University, Canada.

Ogilvie-Harris, D., Botsford, D., & & Hawker, R. (1993).

Elderly patients with Hip Fractures: Improving

outcome with the use of Care Maps with High-Quality

Medical and Nursing Protocols. Journal of Orthopaedic

Trauma, 7(5), 428-437.

O'Neill, E. S., & Dluhy, N. M. (2000). Utility of structured

care approaches in education and clinical practice.

Nursing Outlook, 48(3), 132-135.

Panzarasa, S., Maddè, S., Quaglini, S., Pistarini, C., &

Stefanelli, M. (2002). Evidence-based careflow

management systems: the case of post-stroke

rehabilitation. Computers and Biomedical Research,

35(2), 123-139.

Peak, D., Guynes, C., & Kroon, V. (2005). nformation

technology alignment planning: A case study.

Information and Management, 42.

Philie, P. (2001). Management of blood-borne fluid

exposures with a rapid treatment prophylactic caremap:

One hospital’s 4-year experience. Journal of

Emergency Nursing, 27(5), 440-449.

Potter, P. (1995). The uses of variance. In Z. K (Ed.),

Managing Outcomes though Collaborative Care: The

Application of CareMapping and Case Management.

American Hospital Publishing Inc.

Reading, S., Sanghi, A., Huda, B., Saravanamutha, J.,

Toms, G., Braggins, F., . . . McEaney, D. (2015).

Maternity Services: Diabetes - Pregnancy, Labour and

Peurperium. Barts Health NHS Trust, Barts Health.

Rotter, T., J, K., Koch, R., Gothe, H., Twork, S., van

Oostrum, J., & Steyerberg, E. (2008). A systematic

review and meta-analysis of the effects of clinical

pathways on length of stay, hospital costs and patient

outcomes. BMC Health Services Research, 8(265).

Royall, D., Brauer, P., Bjorklund, L., O’Young, O.,

Tremblay, A., Jeejeebhoy, K., . . . Mutch, D. (2014).

Development of a dietary management care map for

metabolic syndrome. Perspectives in Practice, 75(3),

132-139.

RWH. (2010). Bladder Management - Intrapartum and

Postpartum. The Royal Women’s Hospital, Guideline:

16/05/2017.

Sackman, J., & Citrin, L. (2014). Cracking down on the cost

outliers. Healthcare financial management, 68(3), 58-

63.

Clinical Caremap Development: How Can Caremaps Standardise Care When They Are Not Standardised?

133

Saint-Jacques H, B. V., J, W., Valcarcel, M., Moreno, P., &

Maw, M. (2005). Acute coronary syndrome critical

pathway: chest PAIN caremap: A qualitative research

study-provider-level intervention. Critical Pathways in

Cardiology, 4(3), 145–604.

Schwoebel, A. (1998). Care Mapping: A common sense

approach. Indian Journal of Pediatrics. Indian Journal

of Pediatrics, 65(2), 257-264.

Smithson, S. (1994). Information retrieval evaluation in

practice: A case study approach. Information

Processing and Management, 30(2).

Solsky, I., Edelstein, A., Brodman, M., Kaleya, R.,

Rosenblatt, M., Santana, C., . . . Shamamian, P. (2016).

Perioperative care map improves compliance with best

practices for the morbidly obese. Surgery, 160(6),

1682-1688.

Stumme, G. (2009). Formal Concept Analysis, in

Handbook on Ontologies. Springer: Berlin.

TCHaW. (2010). Abdominal Wall Defects in Neonates:

Initial, pre and post-operative management Practice

Guideline. The Children’s Hospital at Westmead,

Guideline No: 2010-0007 v2.

Tellis, W. (1997). Application of a case study methodology.

The Qualitative Report, 3(3).

Thompson, D., Berger, H., Feig, D., Gagnon, R., Kader, T.,

Keely, E., Vinokuruff, C. (2013). Clinical Practice

Guidelines: Diabetes and Pregnancy. Canadian Journal

of Diabetes, 37, S168-S183.

Thompson, G., deForest, E., & Eccles, R. (2011). Ensuring

diagnostic accuracy in pediatric emergency medicine.

Clinical Pediatric Emergency Medicine, 12(2), 121-

132.

Vaismoradi, M., H, T., & Bondas, T. (2013). Content

analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for

conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing and

Health Sciences, 15(3), 398-405.

Valenstein, P. (2008). Formatting pathology reports:

applying four design principles to improve

communication and patient safety. Archives of

Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, 132(1), 84.

van de Klundert, J., Gorissen, P., & Zeemering, S. (2010).

Measuring clinical pathway adherence. Journal of

Biomedical Informatics, 43(6), 861-872.

WAHealth. (2013). Diagnostic Imaging Pathways:

Bleeding (First Trimester). Imaging Pathways, Western

Australia Health.

Wang, L., Miller, M., Schmitt, M., & Wen, F. (2013).

Assessing readability formula differences with written

health information materials: Application, results, and

recommendations. Research in Social and

Administrative Pharmacy, 9(5), 503-516.

Wilson, D. (1995). Effect of managed care on selected

outcomes of hospitalised surgical patients. Thesis in

fulfilment of the degree of Master of Nursing,

University of Alberta, Canada.

Yazbeck, A. (2014). Reengineering of business functions of

the hospital when implementing care pathways.

Doctoral Dissertation, Faculty of Economics,

University of Ljubljana.

Ye, Y., Jiang, Z., Diao, X., Yang, D., & Du, G. (2009). An

ontology-based hierarchical semantic modeling

approach to clinical pathway workflows. Computers in

biology and medicine, 39(8), 722-32.

Yin, R. (2011). Applications of Case Study Research. Sage

Publications.

Zander, K. (1992). Quantifying, managing and improving

quality: Part 1: How CareMaps link C.Q.I. to the

patient. The New Definition, 1-3.

Zander, K. (2002). Integrated care pathways: Eleven

international trends. Journal of Integrated Care

Pathways, 6, 101-107.

Zarzuela, S., Ruttan-Sims, N., Nagatakiya, L., &

DeMerchant, K. (2015). Defining standardisation in

healthcare. Mohawk Shared Services, 15.

HEALTHINF 2019 - 12th International Conference on Health Informatics

134