Empathic Interaction: Design Guidelines to Induce Flow States in

Gestural Interfaces

Loup Vuarnesson

ENSADLab / SpatialMedia, PSL University, 31 rue d’Ulm, Paris, France

EMOTIC, 13 rue Crucy, Nantes, France

Keywords:

Interaction, Improvisation, Collaboration, UX Design, Flow, Anthropomorphism, NUIs.

Abstract:

The argument of this article is to propose design guidelines favoring the exploration and appropriation of an

interface by a novice user, by drawing inspiration from the mechanisms of adaptation and perceptive loops

in improvisation activities. We want to create sensitive digital experiences, accessible to as many people as

possible, and dynamically adapt their behavior and their interface to the activity and to the emotional state of

the users. Our hypothesis is that such a design would favor the emergence of Flow states, leading to the setting

up of a ”social contract” between the user and his interface.

1 INTRODUCTION

This research in Interactive Design is at the crossroads

between Arts and Sciences and stems directly from

the observation and experience of complex psycho-

logical phenomena, related to creativity or emotional

amplification. The optimal experience - or Flow - a

state of absolute mental absorption, that can be lived

alone or shared with others in a sporting or creative

activity, is in some ways the starting point. We are in-

terested in the mechanisms linking an individual to his

tool, context, or partners / adversaries, and sometimes

leading to states of intense immersion, emotional con-

tagion, creative amplification, and more generally to

the feeling of being embodied with the experience.

We will connect the study of these phenom-

ena with User Experience (UX) concepts and de-

sign methods, and from this perspective we will pro-

pose several design guidelines to induce Flow state

occurence in digital experiences. We will conclude

by presenting two research projects to support these

propositions.

2 CONTEXT

2.1 Optimal Experience, Empathy and

Creative Amplification

”I developed a theory of optimal experience based on

the concept of Flow — the state in which people are

so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to

matter; the experience itself is so enjoyable that peo-

ple will do it even at great cost, for the sheer sake of

doing it.” (Cs

´

ıkszentmih

´

alyi, 1990).

In the various testimonies collected during his works

on happiness and creativity, Mih

´

aly Cs

´

ıkszentmih

´

alyi

was able to identify multiple activities in which this

quasi-mystical state could occur. Described as deeply

inscribed in the moment, and yet disconnected from

time and from the environment, Flow gives to the one

who lives it a feeling of empowerment. The subject is

then at the maximum of his capacities, of his creative

potential, he enters a state of jubilation and happiness,

for a moment that he would like to see it last infinitely.

”. . . a strange calmness I hadn’t experienced in any

of the other games. It was a type of euphoria; I felt I

could run all day without tiring, that I could dribble

through any of their teams or all of them, that I could

almost pass through them physically. I felt I could not

be hurt.” (Fish, 2007).

Here is a testimony of the legendary football player

Pel

´

e, which closely coincides with many other expe-

riences reported to Cs

´

ıkszentmih

´

alyi by dancers, ath-

letes, musicians, mountaineers. In those experiences

we encounter systematically an absence of effort, the

idea to be in the zone, being carried by the current, in

a state of grace, harmony.

In addition to the feeling of invincibility and zero ef-

fort, participants frequently relate:

• Attention and intense focus on the present mo-

ment.

160

Vuarnesson, L.

Empathic Interaction: Design Guidelines to Induce Flow States in Gestural Interfaces.

DOI: 10.5220/0007524301600167

In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications (VISIGRAPP 2019), pages 160-167

ISBN: 978-989-758-354-4

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

• A feeling of control over the situation or activity.

• The feeling of being able to succeed the proposed

task.

• An experience of intrinsically rewarding, self-

sufficient, autotelic activity.

Being in contact with these different sportive and

artistic backgrounds, Cs

´

ıkszentmih

´

alyi was able to

detect that the existence of this modified state of

consciousness was appearing when the participants

were on the edge of their own physical or creative

limits. Many studies followed Cs

´

ıkszentmih

´

alyi’s to

try to level, provoke, or share this state of Flow

(Mladenovi

´

c et al., 2017), (Chen, 2007). Several re-

lations have been attempted with spiritual concepts,

such as mindfulness meditation techniques, Wu-wei

or the non-action principle among the Taoists, dhyana

among the Buddhists. However, most studies seem to

agree on some of the essential conditions to help the

state of Flow appear:

• The user must be involved in the activity with

clearly stated goals.

• The activity should provide immediate feedback

so that the user can better adjust his performance

and maintain his Flow status.

• An optimal balance must be found between the

challenges perceived by the user and his own abil-

ities. The user must be confident about his ability

to perform the task.

Figure 1: Mental state in terms of challenge level and skill

level.

We can see in the different areas of this graph the mul-

tiple mental states that can occur when we vary the

level of challenge according to the skills of the user.

A challenge beyond the expectations or abilities of the

subject leads to stress and anxiety, making him leave

the area of comfort and efficiency. On the opposite, a

participant who is too qualified for the task is subject

to boredom.

On this graph the Flow appears in the upper right

corner, when the balance between the levels of chal-

lenges and capacities is ideal. The subject must be

confronted with stimulating solicitations, on which he

will be able to exercise his savoir faire while develop-

ing and enriching his capacities. Without this, he will

move into one of the other states presented, such as

apathy and indifference, reflecting his lack of involve-

ment in the task.

Flow theorists insist on the importance of creat-

ing a proper environment allowing the Flow ex-

perience in everyday life, in private life, as well

as in the workspace (Cs

´

ıkszentmih

´

alyi, 2013).

Cs

´

ıkszentmih

´

alyi connects it very closely to notions

of creativity, productivity, or happiness:

”[The Flow is] A state in which people are so in-

volved in an activity that nothing else seems to mat-

ter; the experience is so pleasant that they will con-

tinue to experience it even at a great cost, for the sheer

pleasure of the experience itself.” (Cs

´

ıkszentmih

´

alyi,

1990).

We refer to an autotelic experience, sufficient in itself,

even if these moments are also the most profitable for

us in the long term:

”The best moments in our lives are not the passive,

receptive, relaxing times ... The best moments usually

occur if a person’s body or mind is stretched to its

limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something

difficult and worthwhile.”

The flow therefore depends on many parameters, the

context and the interlocutors being the main ones.

2.2 Interaction, Improvisation and

Emotional Contagion

Flow can also be experienced as shared in group ac-

tivities, such as dance, music and/or sport. (Borderie,

2015).

”The secret of football and the smooth running of

teams is harmony. True harmony is equivalent to per-

fection, to beauty (...) Harmony can be anywhere: in

the music, in the body and in the spirit, in the will of

a football team to win victory (. . . ). Harmony in a

team means that everyone plays together and thinks

like One.” (Cantona and Fynn, 1996).

A football team will sometimes appear scattered, dis-

tressed, or lost; and sometimes will seem to reach mo-

ments of perfect coordination, where all the individ-

ual talents express themselves and form an insepara-

Empathic Interaction: Design Guidelines to Induce Flow States in Gestural Interfaces

161

ble entity. In these situations, the results can reach

levels beyond all expectations.

In dance or musical improvisation - autotelic ex-

periences by essence - the goal is in the exploration

rather than the completion. Each participant will pro-

pose, receive, then propose again, thus unfolding the

course of the shared experience, in a balance between

tensions and harmonies. These events involve com-

plex interaction strategies between the participants,

involving many expressive, perceptive, contextual and

emotional parameters. The principles of mirror neu-

rons, or empathy, resonate closely with these dynam-

ics of coordination and affective tuning.

The desired goal is by no means discrete but mul-

tiple, it is at the same time an exploration of one’s

body, one’s instrument, and at the same time to push

one’s own limits, to set oneself a challenge, for him as

for others; it is at the same time A game, a surprise,

it can be humorous, as it can be infuriating, violent or

passionate.

A successful improvisation performance does not

lie in the fulfillment of a predefined goal, but in the

quality and renewal of the ideas proposed, their ap-

propriateness to the context, and of course in the plea-

sure felt and the emotion shared with the partners and

the viewers.

3 FLOW IN AN INTERFACE

3.1 Aim of the Study

The argument of this article is to propose design

guidelines favoring the exploration and appropriation

of an interface by a novice user, by drawing inspi-

ration from the mechanisms of adaptation and per-

ceptive loops in improvisation activities. We want

to create sensitive digital experiences, accessible to

as many people as possible, and dynamically adapt

their behavior and their interface to the activity and

to the emotional state of the users. Our hypothesis is

that such a design would favor the emergence of Flow

states, leading to the setting up of a ”social contract”

between the user and his interface (Bianchini et al.,

2015).

A central idea in any form of improvisation is the

tuning and good communication between the individ-

uals involved. In the context of an interactive experi-

ence, the emergence of a participant’s feeling of free-

dom requires that his power and his grip over it are

clear, and that the effects produced are immediately

perceived. To base our interactional paradigm we can

not ask the human to express themselves in the native

language of the machine, but we can instead draw in-

spiration from inter-human modes of communication.

Empathic phenomena work by identification, by

projecting oneself into the body of another. We must

be able to translate all the information coming from

the user to the machine, to reveal his ease and emo-

tional state so that the interface can adapt to it.

This proposal and this entire research focus there-

fore on the expressive dynamics that can be envisaged

between the user and the system. Coordination in cre-

ative improvisation is the result of multiple adapta-

tions based on the entire perceptual and cognitive do-

main; drawing inspiration from it for an interface de-

sign implies to determine which information can be

observed from the user and how it can be reflected

with an adaptation from the interface.

We will detail what implies the idea of a coordi-

nated interaction for the user and the machine.

3.2 Adapt to the User – Movement

Qualities

We want to give the user the feeling of being under-

stood by the system, to give him the will to propose

and improvise through it, to explore it freely and to

bond a new and personal form of exchange. We need

therefore to identify what we can track to design our

adaptive and pseudo-empathic process.

Many models exist for the evaluation of a user in a

digital context. These models list a certain number of

criteria specific to the cognitive, physical, psycholog-

ical and emotional domains. For our research we seek

to identify the characteristics that have an influence on

the phenomena of emotional and empathic contagion.

Further explorations will be conducted on the actual

characteristics during a co-creative activity with the

ArTiculations project. In this study, two participants

will interact in a virtual reality experience via a sim-

plified representation of their movements. We want

to analyse quantitatively the observed behaviours and

collect the emotionnal outlines of their experiences

(see 4.2.2).

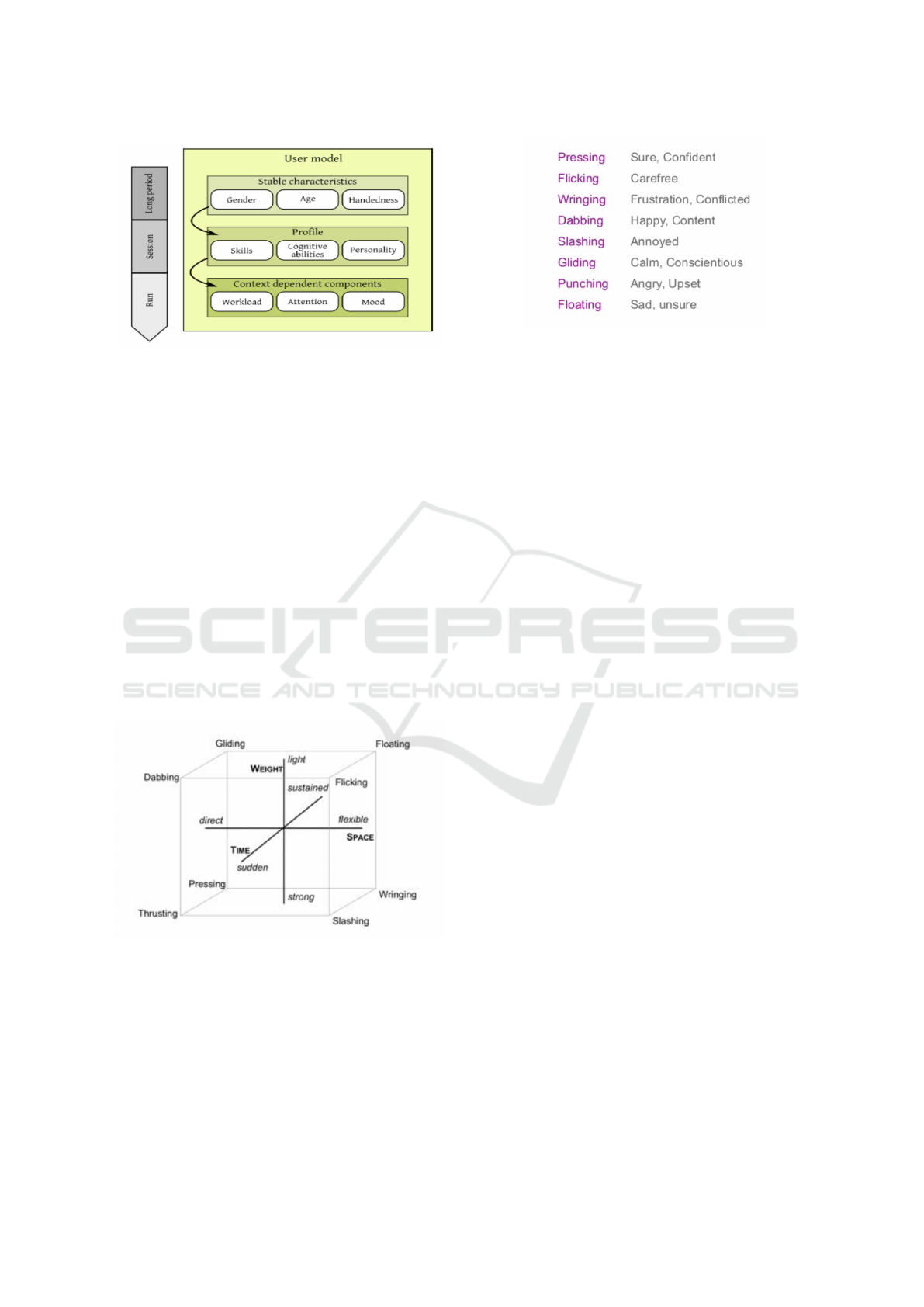

In Figure 2, some characteristics are distinguished

through several temporalities. Some will remain fixed

from one session to another (the gender, the physical

characteristics ...), others can change radically as the

experience is lived (the emotional state, the cognitive

load ...). For reasons of comfort and portability we

do not want to equip the users with sensors, or asking

them to fill questionnaires beforehand.

We will build our analysis engine on the basis of

the clues collected during the actual experience, and

centered on the core of our proposal: the expressive

and intuitive potential of the gesture.

HUCAPP 2019 - 3rd International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

162

Figure 2: User Model – arranged from the least stable (con-

text dependant), to the most stable (stable characteristics).

There is something deeply intimate in the way we

move, in the way we express ourselves through ges-

tures. A movement whether it is planar or in space

brings much more nuances and expressiveness than a

discrete touch of a keyboard key. An interactive ges-

tural paradigm makes it possible to think of a form

of freedom of use that is wider, more personal, more

sensitive.

We are particularly interested here in the works of

Rudolf Laban, as well as ones based on his notions of

effort and qualities of gesture (Laban and Lawrence,

1947), (Bernhardt, 2007).

Theses qualities distinguish movements by their

intentions, their characters, and seek to explain them

verbally. We use action names like floating, slashing,

pressing, punching, as well as attributes such as direc-

tivity, contraction, suddenness, fluidity, fragility...

Figure 3: Laban’s gesture qualities axises.

It is possible to associate emotions to theses ges-

tures, to detect evolutions in nature and intensity, and

thus to observe and react to them.

These qualities, initially created and used to de-

scribe the danced gesture, have been appropriated

by digital artists and researchers to compose the in-

teractive basis of their works or studies in cogni-

tive psychology (Niewiadomski et al., 2017), (Fdili

Figure 4: Emotional states associated with movement qual-

ities.

Alaoui et al., 2011). They allow, thanks to real-time

qualification tools (EyesWeb for example) to evalu-

ate the users’ performance in a more subtle, sensitive

way. It is possible today to obtain a state of these qual-

ities of motion in realtime, and to think of appropriate

reactions from the point of view of the interface.

However, it is necessary to identify how we could

define and base these reactions.

3.3 Intuition in the Experience – NUIs /

UX

In the 90’s the idea of natural user interfaces (NUI)

appeared. Popularized by Microsoft with inventions

like Kinect or Microsoft Surface, this concept brought

the idea of intuitiveness into the development of digi-

tal interfaces.

Through gestural interfaces, whether on smart-

phones, touch tables, or via motion capture, the NUIs

have offered a new interactive paradigm, giving op-

portunities to use linguistic forms more faithful and

close to our modes of inter-human communication.

They appear as a response to the WIMP era (windows,

icons, mouse, pointer) by simplifying the display, and

dynamically adapting the complexity of the proposed

commands as the user gains ease of use.

The desired effect is a lower cognitive load and an

immediate user comfort.

Rachel Hinman, UX researcher at Nokia Re-

search, give us some basic principles for the devel-

opment of a good NUI (Hinman, 2011):

• Performance Aesthetics - Unlike GUI experiences

that focus and privilege accomplishment and task

completion, NUI experiences focus on the joy of

doing. NUI experiences should be like an ocean

voyage, the pleasure comes from the interaction,

not the accomplishment.

• Direct Manipulation - Unlike GUI interfaces,

which are enabled by indirect manipulation

Empathic Interaction: Design Guidelines to Induce Flow States in Gestural Interfaces

163

through a keyboard and mouse, natural user inter-

faces enable users to interact directly with infor-

mation objects. Touch screens and gestural inter-

action functionality enable users to feel like they

are physically touching and manipulating infor-

mation.

• Scaffolding - Successful natural user interfaces

feel intuitive and joyful to use. Unlike a success-

ful GUI in which many options and commands

are presented, a successful NUI contains fewer

options with interaction scaffolding. Good NUIs

supports users as they engage with the system and

unfold or reveal themselves through actions in a

natural way.

• Seamlessness - GUIs require a keyboard and

mouse for interaction with a computing systems.

Touchscreens, sensors embedded in hardware,

and the use of gestural UIs allow NUI interactions

to feel seamless for users because interactions are

direct. There are fewer barriers between the user

and information.

When Rachel Hinman speaks about intuition, she ap-

peals to what is already known by the user. Design-

ing an intuitive and accessible interface for a large

number of people requires to first of all understand

the expertise of the users regarding NUI’s, in relation

to other interactive paradigms that they may have al-

ready experienced (or integrated).

Gord Kurtenbach, director of research at Au-

todesk tells us:

”There is no such thing as natural or intuitive in-

terface [...] Effective user interface design is a very

carefully controlled skill transfer - we design inter-

faces so users can take their skills from on situation

and re-apply them to a new situation.” (Widgor and

Wixon, 2011).

Same as in the previous section regarding the state

of Flow, we are talking about being embodied in

the experience. The interface becomes an ”exten-

sion of the hand”. A good NUI is therefore based

on metaphors borrowed from the reality, that the user

will recognize and take over easily. In this way, he

will be able to integrate the experience instantly, and

unfold more complex functionalities while being in

action. The system accompanies and guides the user

throughout the whole experience.

3.4 Adaptation from the Designer’s

Perspective – Hassenzahl’s UX

Model

More concretely, several tracks can be explored to

base the idea of adaptive interfaces. We choose to

focus here on the works of Marc Hassenzahl (Has-

senzahl, 2005), (Hassenzahl, 2018):

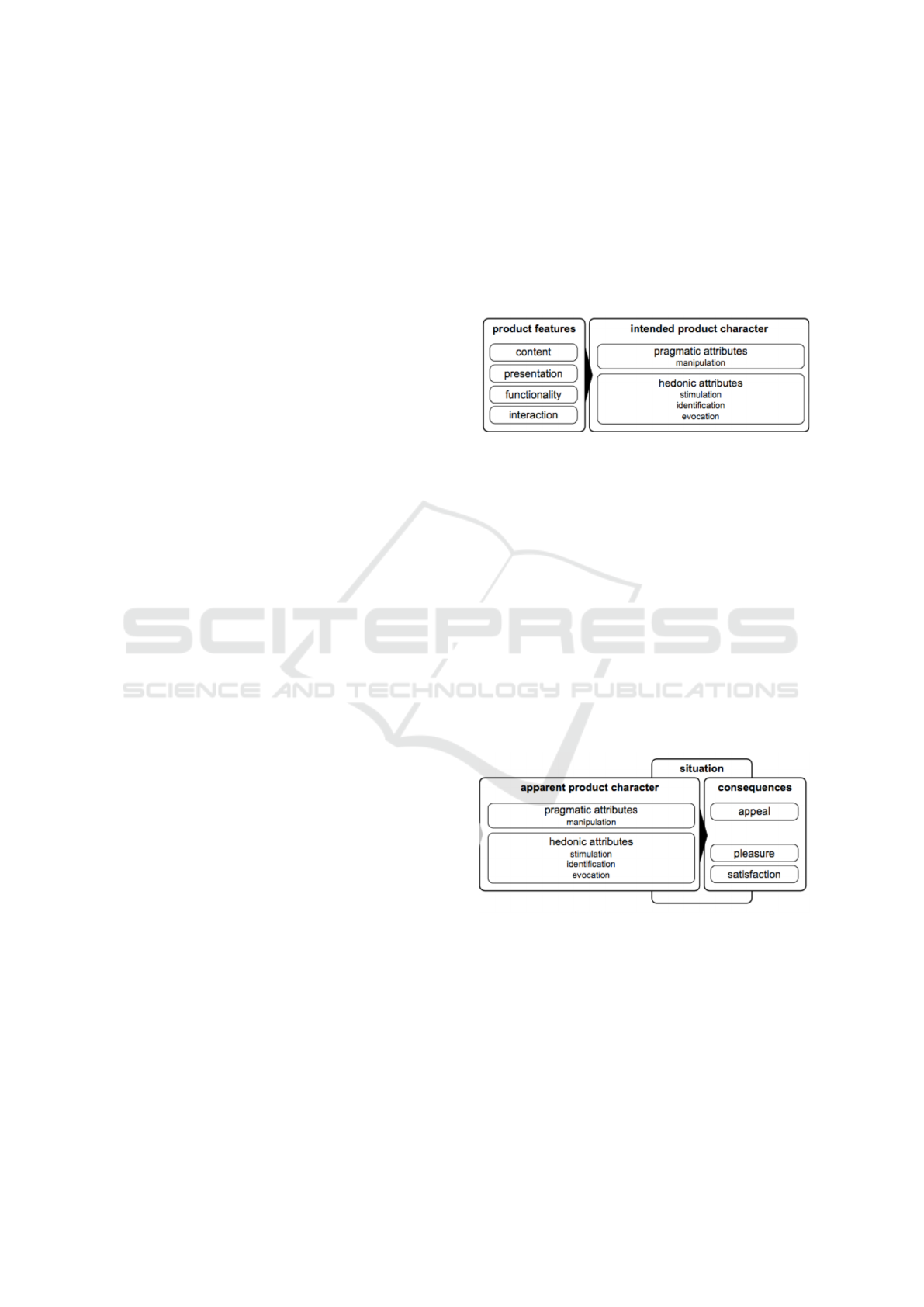

Figure 5: Hassenzahl UX Model - Designer Perspective.

Hassenzahl explains here the links between the

user and the product: the UX is seen from the de-

signer’s side as a set of contents / presentations / func-

tionnalities / interactions. That is, as designers, what

we can consider as plastic and adaptable.

These characteristics are then merged into two types

of attributes :

• The pragmatics, that concern what can be manip-

ulated, what has a practical use. These attributes

refer to the functionalities of the product.

• The hedonics, that concern the elements in charge

of improving one’s well-being. These attributes

refer to the stimulation, the identification of the

user.

Figure 6: Hassenzahl UX Model - User Perspective.

On the user’s side, these two types of attributes are

translated into attractiveness, pleasure and satisfac-

tion. Each digital product has these two types of at-

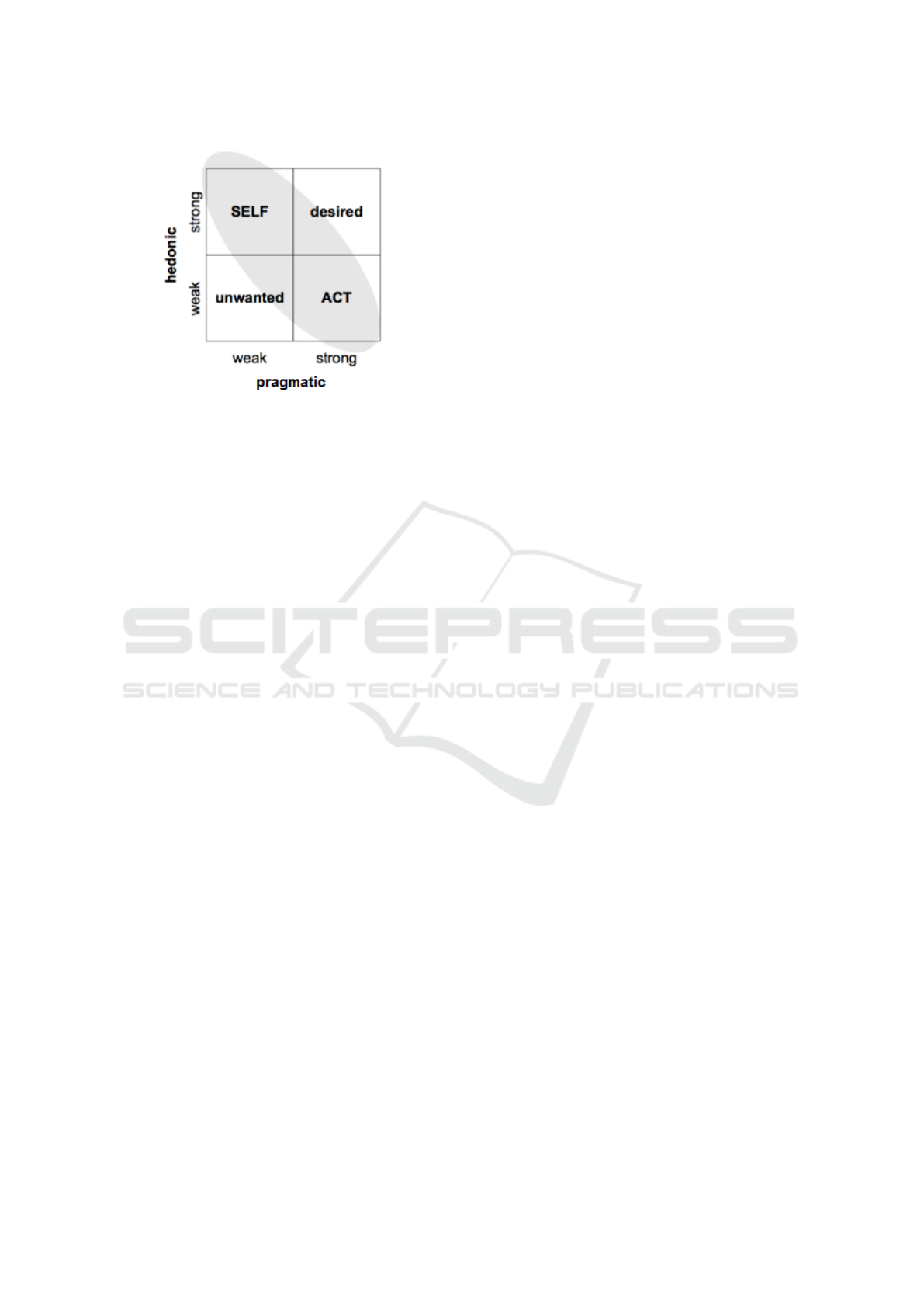

tributes, unequally balanced:

If the pragmatic aspect is particularly strong, we are

talking about ACT products, more linked to objectives

and tasks, which seek to bring satisfaction.

If the hedonic aspect is in foreground, we talk about

SELF products, linked to the user himself, where we

want to induce pleasure.

HUCAPP 2019 - 3rd International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

164

Figure 7: Hassenzahl UX Model.

Hedonics does not have the same purpose as Prag-

matics and there are situations where the need for

stimulation, novelty or attractiveness will be strong;

on the contrary, sometimes this need will be more di-

rected towards a high rate of accomplishment of tasks.

The general emotional reaction depends on how a

product is momentarily suitable for a situation. The

designer will ideally seek the appropriate balance be-

tween pragmatic and hedonic attributes, playing on

both utility and usability, both on the senses and the

seduction.

This formulation makes it possible to categorize

better the type of adaptation and the spirit of the ex-

periment that we consider to develop. We will now

outline the key points of our proposal.

4 PROPOSITION

4.1 UX Design Guidelines

By comparing the different notions presented here,

we propose a set of objectives for the design of ex-

periences inducing the appearance of a state of flow

among users of all kinds :

1. The interface must involve metaphors inspired by

reality.

We need to allow a transfer of skills and remain intu-

itive for novice users. To this purpose, we propose a

focus on the design of biomorphic entities animated

by movements with life-relevant dynamics. In order

to create a form of empathy and an emotional lan-

guage immediately noticeable by the user, we will

play with the behavior of these visual entities by mod-

ulating their movements explicitly.

2. The user must have an immediate feedback of his

implicit and explicit actions.

Any gestural information emitted by the user should

be considered relevant and generate a reaction by the

interface. We will base the adaptation of the Hassen-

zahl’s PRESENTATION and INTERACTION criteria

on all the information coming from the analysis of the

qualities of movement.

3. The interface must adapt its behavior as the user

improves.

We recommend here an adaptation of the functionali-

ties as well as the behaviors of the metaphors inspired

by reality.

The ACT aspect of the experience must be designed

as dynamic. The interface must unfold its complexity

and functionality in a consistent manner. The basics

need to be mastered for more advanced concepts to

become available.

4. The interface must be creative and surprising.

Modeling our study on the principles of autotelic ex-

periments, the SELF aspect must be particularly de-

veloped. The interface should not be completely pre-

dictable, on the contrary it should provoke the desire

of exploration to the user, and make him adjust his

own gestural activity. For that, we plan to oscillate the

adaptivity of the interface between a tuning accord-

ing to the qualities of the user’s movements on the

one hand, and the creation of a certain degree of ten-

sion on the other hand. A perfect tuning would lead

to comfort and harmony. An ideal degree of tension

would lead to a form of resistance and playfullness.

4.2 Experiments

We will conduct a research around these design guide-

lines through two Arts / Sciences research projects,

each highlighting a different part of this study.

4.2.1 Tamed Cloud

”Tamed Cloud, Sensitive interactions with a behav-

ioral cloud of spatialised information” is a research

conducted by Ensadlab / Spatial Media - Reflective

Interaction in partnership with IBM, and which is

part of the actions of the Cognition Carnot Institute

around the theme ”Artificial and Cognitive Intelli-

gence”. It proposes an articulation of human’s biolog-

ical, biomechanical and psychological models with

quantitative data.

The project integrates a user into a virtual real-

ity experience, and explores the possibility of a truly

responsive relationship based on gesture and speech

Empathic Interaction: Design Guidelines to Induce Flow States in Gestural Interfaces

165

Figure 8: Ingame footage of Tamed Cloud.

with large masses of information thought as a living

and malleable entity.

In the current state of the project, the information

consists of floating paintings taken from the MOMA

catalog in New York.

The paintings encircle the user and move like a

swarm. The user can grab one or more of them and

move them into space. He can also ask the cloud, by

using voice commands, to organize itself by color, or

by date, in which case all the paintings are reordered

around him in the desired mode.

We consider to apply the previous proposals to this

project, and to design a ”character” to the cloud that

would be changeable, unpredictable, but however re-

lated to the movements made by the user. The user

would naturally be invited to explore his own gestural

vocabulary in order to understand which of his actions

could have an impact on the cloud’s behavior.

4.2.2 ArTiculations

This second research project was submitted as part of

the EUR ArTeC call for projects and aims to explore

the processes involved in collaborative artistic cre-

ation situations. We want to study, in the controlled

context of a virtual reality scene, how the dynamics

of interaction by the gesture favor the emergence of

creative behaviors.

The system will immerse two people dancing and

improvising freely together, represented in a minimal-

ist way. Their movements will be captured in real

time while their physiological states will by analyzed

a posteriori, linked to a review of their lived experi-

ence.

Our goal is to identify the emergence of intersub-

jective forms and dynamics of creative interactions.

5 CONCLUSION

This research raises questions that cross multiple

fields like UX design, cognitive psychology, arts and

creativity, but focuses on something deeply connected

with one’s well-being and self-actualization. In all

the fields of interactive media, we see the spectator

becoming actor, and artworks often being described

as experiences. With the rise of virtual reality, adap-

tive learning, artificial intelligence and voice assis-

tants, we can now extend our capabilities by exploring

new situations and activities, by experiencing new in-

teractions modalities and linguistic (or non-linguistic)

models.

Adaptive interface designers are keen on creat-

ing smart tools that align with the way people live,

think, or feel. They seek a projection in the user’s

life, by tuning well their product and inducing proper

emotional responses. The product may have multiple

forms of use, and may be conceived for different sup-

port devices. First and foremost, it has to be designed

for the user, who will hopefully remain subject to un-

predictable changes.

Trying to adapt in realtime an interface to the ease

of use and the gestural activity of the user is an exten-

sion of this idea. We proposed here a set of objectives

to reach a more human way of thinking an interaction,

allowing the user to inject a bit of his unpredictabil-

ity to the system, which will react to him in the same

manner.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Research funded by the company EMOTIC, con-

ducted within the research group SpatialMedia En-

sadLab (EnsAD) and under the doctoral program

SACRe, PSL University.

I would like to thank Dionysis Zamplaras and

Franc¸ois Garnier for their precious help and advices,

and Asaf Bachrach for the inspiring insights.

REFERENCES

Bernhardt, D., 2007. Posture, Gesture and Motion Quality:

A Multilateral Approach to Affect Recognition from

Human Body Motion. In Accii’07: Proceedings of the

doctoral consortium at the second international con-

ference on affective computing and intelligent interac-

tion.

Bianchini, S., Bourganel, R., Quinz, E., Levillain, F., and

Zibetti, E., 2015. (mis)behavioral objects. In Empow-

ering users through design. Springer.

HUCAPP 2019 - 3rd International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

166

Borderie, J., 2015. La qu

ˆ

ete du team flow dans les

jeux vid

´

eo coop

´

eratifs: apports conceptuels et

m

´

ethodologiques (Unpublished doctoral dissertation).

Universit

´

e Rennes 2.

Cantona, E., and Fynn A., 1996. Cantona on Cantona. An-

dre Deutsch; 1st edition (1996).

Chen, J., 2007. Flow in games (and everything else). Com-

munications of the ACM, 50(4).

Cs

´

ıkszentmih

´

alyi, M., 1990. The psychology of optimal ex-

perience. New York, Harper Collins.

Cs

´

ıkszentmih

´

alyi, M., 2013. Creativity: Flow and the psy-

chology of discovery and invention. Harper Perennial.

Fdili Alaoui, S., B, Caramiaux, B., and Serrano, M., 2011.

From dance to touch: movement qualities for interac-

tion design. In Chi’11 extended abstracts on human

factors in computing systems.

Fish, R. L., 2007. My life and the beautiful game: The au-

tobiography of pel

´

e. Skyhorse Publishing In.

Hassenzahl, M., 2005. The thing and I: Understanding the

relationship between user and product.

Hassenzahl, M., 2018. The thing and I: Understanding the

relationship between user and product. In Funology 2.

Springer

Hinman, R., 2011. What are the basic principles of nui

(natural user interface) design? Available from:

http://www.toastmasters.org.https://www.quora.com/

What-are-the-basic-principles-of-NUI-Natural-User-

Interface-design).

Laban, R., and Lawrence, F. C., 1947. Effort. Macdonald &

Evans.

Mladenovi

´

c, J., Mattout J., and Lotte, F., 2017. A generic

framework for adaptive eeg-based bci training and

operation. arXiv preprint arXiv: 1707.07935.

Niewiadomski, R., Mancini, M., Piana, S., Alborno, P.,

Volpe, G., and Camurri, A. 2017. Low-intrusive

recognition of expressive movement qualities. In Pro-

ceedings of the 19th ACM international conference on

multimodal interaction.

Wigdor, D., and Wixon, D., 2011. Brave nui world: de-

signing natural user interfaces for touch and gesture.

Elsevier.

Empathic Interaction: Design Guidelines to Induce Flow States in Gestural Interfaces

167