Skill Confidence Ratings in a MOOC: Examining the Link between Skill

Confidence and Learner Development

Karen von Schmieden, Thomas Staubitz, Lena Mayer and Christoph Meinel

Hasso Plattner Institute, University of Potsdam, Prof.-Dr.-Helmert-Strasse 2-3, 14482 Potsdam, Germany

Keywords: Online Learning, MOOC, Learner Skill Confidence, Learner Development.

Abstract:

This paper explores the development of perceived learner skill confidence in a programming MOOC by apply-

ing and analyzing a new Skill Confidence Rating (SCR) survey. After cleaning datasets, we analyze a sample

of n = 1689 for the first course module and n = 1147 for the second course module. Results show that on av-

erage, learners perceive their skills more confidently after taking a module. The initial confidence per module

differs. We could not find a correlation between perceived learner confidence and learner performance in this

course.

1 INTRODUCTION

Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) have great

potential for learners worldwide by offering unre-

stricted access to educational resources, both inside

and outside of higher education (Yuan and Powell,

2013). Unfortunately, course instructors often strug-

gle to create meaningful digital learning experiences

(Mackness et al., 2010; Haggard et al., 2013). With

massive numbers of learners attending, course in-

structors have little opportunity to gather informa-

tion about learner development, and how learners per-

ceive the development of their skills. We propose

the assessment of learner skill confidence to better

understand the development of learners in MOOCs,

and to consequently improve the effectiveness of dig-

ital learning experiences. To explain this endeavor,

we will first contextualize the terms of ”skill” and

”learner confidence” in literature to clarify the pur-

pose, development and testing of our Skill Confidence

Rating (SCR) survey. Next, we describe the experi-

mental setup and results of the SCR in a MOOC on

Java for beginners, which consisted of several mod-

ules. We set out to assess the link between per-

ceived skill confidence and learner development in

this MOOC.

1.1 Research Question

Can we draw conclusions about learner development

in a programming MOOC based on learners’ per-

ceived skill confidence? a) Is there a mean increase

in learner skill confidence between pre and post as-

sessment per module? b) Is there a shift in the initial

skill confidence (pre survey) from module 1 to mod-

ule 2? c) Did learners with a high skill confidence

gain from pre to post survey receive a high amount of

points during the course?

2 SKILL ACQUISITION

The term ’skill’ generally describes a proficiency

developed through training or experiences (Annett,

1989). Knowledge, in comparison, is regarded as

the theoretical or practical understanding of a sub-

ject. Stuart E. Dreyfus and Hubert L. Dreyfus de-

veloped a five-step model of skill acquisition by ex-

emplifying the learning process of language learn-

ers, chess players, and pilots (Dreyfus and Dreyfus,

1980) and later by describing driving lessons. In their

model, a student passes through the stages of ’novice,

advanced beginner, competence, proficiency, and ex-

pert’. An increase in proficiency is marked by a dis-

association from rigid adherence to rules and the de-

velopment of an intuitive reasoning (Dreyfus, 2004).

Decision-making thus becomes a tacit action. Al-

though students in a focused online course may only

pass through one of these defined phases for a skill,

an increase in skill proficiency is possible. With re-

gard to the temporal position of skill development

in training phases, we postulate that skill acquisition

takes place in the ”during training phase” as defined

by Salas et al. (Salas et al., 2012); while the ”after

von Schmieden, K., Staubitz, T., Mayer, L. and Meinel, C.

Skill Confidence Ratings in a MOOC: Examining the Link between Skill Confidence and Learner Development.

DOI: 10.5220/0007655405330540

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2019), pages 533-540

ISBN: 978-989-758-367-4

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

533

training phase” marks learners’ skill transfer. In the

following, we refer to findings from a study by Bell

and Kozlowski (Bell and Kozlowski, 2010) to illus-

trate this point. They establish self-regulation systems

as a component affecting the junction between a train-

ing intervention and training outcomes. They outline

”practice behaviors”, ”self-monitoring”, and ”self-

evaluation reaction” as the paramount elements for

creating learner-centered training designs. ”Practice

behaviors” as a behavioral component refers to ”how

[learners] allocate effort [...] during practice aimed at

skill improvement” (p. 267). ”Self-monitoring” as a

cognitive component refers to ”how [learners] focus

their cognitive attention and reflect on their progress

toward desired objectives” (p. 267). ”Self-evaluation

reaction” as an affective component refers to learn-

ers’ ”affective reactions to goal progress”, e.g., self-

efficacy (p. 267, see also (Salas et al., 2012).

3 LEARNER CONFIDENCE

In this research, we are interested in learners’ confi-

dence regarding their skill acquisition. Albert Ban-

dura explored the concept of learner confidence by

coining the term self-efficacy. In the context of learn-

ing, self-efficacy describes the learner’s belief that

their abilities and knowledge are sufficient to suc-

ceed at a task (Bandura, 1986). Learner confidence

is thus not a fixed state. Scholars generally describe

it as situation-specific, meaning that it can be influ-

enced by internal and external factors (Moller, 1993).

While Bandura deems ”confidence” a colloquial term

to approach self-efficacy, he did use the word in his

surveys to make survey items understandable to par-

ticipants. Other scholars, such as John Keller, apply

the term of learner confidence throughout their work.

According to Keller (Keller, 1987), confidence is the

interplay between learners’ desire for or expectancy

of success, and their fear of failure. Keller and Suzuki

summarize the learner confidence term by building on

Weiner’s attribution theory (Weiner, 1974). They ar-

gue that learners need to ”attribute their successes to

their own abilities and efforts rather than to luck or

the task being too easy or difficult” (2014, p. 231).

Keller and Suzuki’s confidence concept (and corre-

sponding course design recommendations within their

learner motivation model) has been applied and vali-

dated in online learning (Keller and Suzuki, 2004).

For this paper, we are exploring the concepts of skill

(acquisition) and Keller’s and Bandura’s concepts of

learner confidence by examining the development of

learner confidence of specific skills. In the con-

text of (online) learning and Massive Open Online

Courses, Bandura’s scale of perceived self-efficacy is

often used to measure the extent ”to which an individ-

ual learner feels confident in their ability to engage

with and complete learning activities” (Hood et al.,

2015). It is furthermore often used in the context of

self-regulated learning (Bandura, 2006; Usher and Pa-

jares, 2008). In assessing learner skill confidence, we

deviate from Bandura’s self-efficacy scale for two rea-

sons: Firstly, we focus on learner’s confidence with

specific skills, and not the entirety of efficacy with

the course’s learning activities. Secondly, we are in-

terested to see how this confidence develops through-

out learning units and the whole course, and if this

development allows us to draw conclusion for course

design and learner support.

3.1 SCR Survey Development

We developed, piloted and tested the Skill Confi-

dence Rating survey for a skill-based Design Think-

ing

1

MOOC prototype. This course ran as a proto-

type in a closed setting on the German MOOC plat-

form openHPI in November 2016 (Taheri et al., 2018)

MOOC prototype. Findings from the course indicated

the usefulness of the SCR, reinforcing us to conduct

the survey with a larger MOOC audience. We opted

for adapting the SCR in a course on object-oriented

Programming in Java. Similar to the Design Thinking

course, this course has a focus on learning skills and

competences rather than on teaching knowledge. The

conveyed programming skills are tied closely to cod-

ing exercises and assignments. This allowed us to put

a focus on learner development.

4 METHODS

4.1 Testing Environment

The SCR surveys were an integral part of the MOOC

on Object-Oriented Programming in Java, which also

ran on the openHPI. Next to an introduction to the

Java programming language and syntax and some ba-

sic programming constructs, the scope of the course

focused on object-oriented techniques and concepts,

such as inheritance and polymorphism. Furthermore,

it included an excursus on object-oriented modeling,

in which the participants were asked to work in teams

1

Design thinking is a user-centered approach for prob-

lem solving and idea development. Stanford University ini-

tially extended and developed Design Thinking education

programs. The approach has been implemented in organi-

zations internationally (Martin, 2009).

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

534

to create a class diagram and code skeleton for a given

task. At the course middle, 9242 learners

2

had en-

rolled for this four-week online course. To keep the

number of surveys in this course at an acceptable

amount, we grouped Week 1 + 2 and Week 3 + 4 in

two modules for measuring skill confidence develop-

ment. These weeks formed a pair with regard to their

content. Besides these two modules, the excursus on

object-oriented modeling formed a third module. The

surveys were positioned before and after the learn-

ing content of all three learning modules (Module 1:

week 1 + 2, Module 2: week 3 + 4, and Module 3:

Excursus).

4.2 SCR Setup

The online course contained three coherent learning

modules, therefore the SCR consisted of three pre

and post tests. The pre SCR questions marked the be-

ginning of a new learning module (e.g., start of week

1) and the post SCR followed at the end of a learning

module (e.g., end of week 2). Participants estimated

their confidence with skills that were central to the

methods covered in each module before and after

taking the module. The example below shows a

question from the survey (in English translation).

Example for question item 1, module 1

Question 1, German:

pre: Wie sicher fuehlst du dich Methoden in Java

zu deklarieren und aufzurufen?

post: ...nach Woche 1 und 2?

Question 1, English Translation:

pre: How confident do you feel with declaring and

invoking methods in Java?

post: ... after week 1 and 2?

The Likert response scale for every question

ranged from 1 (”ueberhaupt nicht sicher”, english:

”not at all confident”) to 10 (”absolut sicher”, english:

”absolutely confident”).

2

We consider the enrollment number at the course mid-

dle as our reference point, as only those participants have

the option to finish the course with an acceptable result.

While we issue a certificate to all participants who have

achieved more than 50% of the available points in the

graded exercises, we know from statements of our users that

many of them only consider a result of 80-100% as accept-

able. Until the end of the course, the number of enrolled

learners had increased to 10,402.

5 ANALYSIS

As a first step, we cleaned all data sets. We only

considered subjects who had filled in both the pre

and post questions per module. We also elimi-

nated subjects with missing values for either pre or

post SCR questions. In the following, we refer to

cleaned datasets that only include subjects who filled

in both pre and post ratings in one module as ”merged

per module”. Likewise, we cleaned datasets that

only include subjects who filled in the pre and post

SCR in both modules (module 1 and 2) as ”merged

across modules”. Subsequently, we calculated means

with standard deviations and confidence intervals for

cleaned and merged datasets per module. Next, we

analyzed the relation between SCR values and per-

formance measures. For performance measures we

looked at learners’ total points received in the course,

and the number of issued records of achievement. To

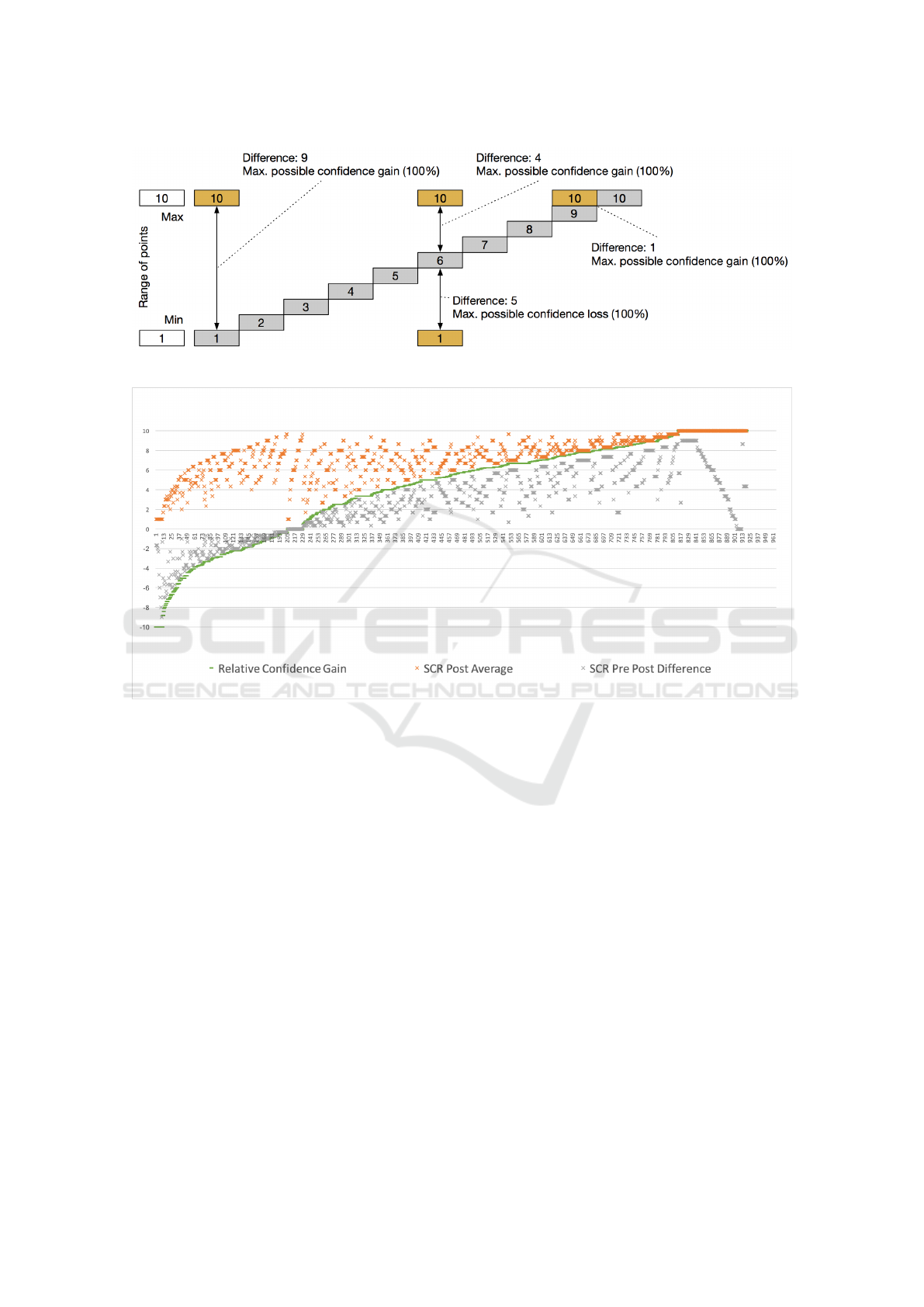

explore this issue, we use the term ”relative confi-

dence gain (RCG)” in this paper. We introduce this

new dimension because the plain difference between

the pre SCR and the post SCR values neglects to take

into account how much perceived confidence a par-

ticipant possibly might have gained or lost between

the surveys. Due to the scale of the survey questions

(1-10), a participant that has started with a pre SCR

of 1 can increase her confidence by 9 points. A par-

ticipant who has started with a pre SCR of 5, how-

ever, can increase their confidence by only 5 points, a

participant who started with 10 cannot increase their

confidence at all. The same applies for a possible de-

crease in the other direction. Hence, if we use the

plain difference between pre and post SCR, the result

would be distorted. The difference would be the same

for a user who starts with pre SCR 1 and ends with

post SCR 2 as for a user who starts with pre SCR 9

and ends with post SCR 10. The first user, however,

only increased their confidence by 11% of the poten-

tially possible increase. The second user, in contrast,

increased their confidence by 100% of the potentially

possible increase. The RCG takes this into account by

including the maximum possible increase or decrease.

Below are the equations for determining the learner’s

gain or loss:

100

max − pre

×

post − pre

max

(1)

100

pre − min

×

pre − post

max

(2)

Equation 1 became effective when the learner had a

gain in confidence, equation 2 became effective when

Skill Confidence Ratings in a MOOC: Examining the Link between Skill Confidence and Learner Development

535

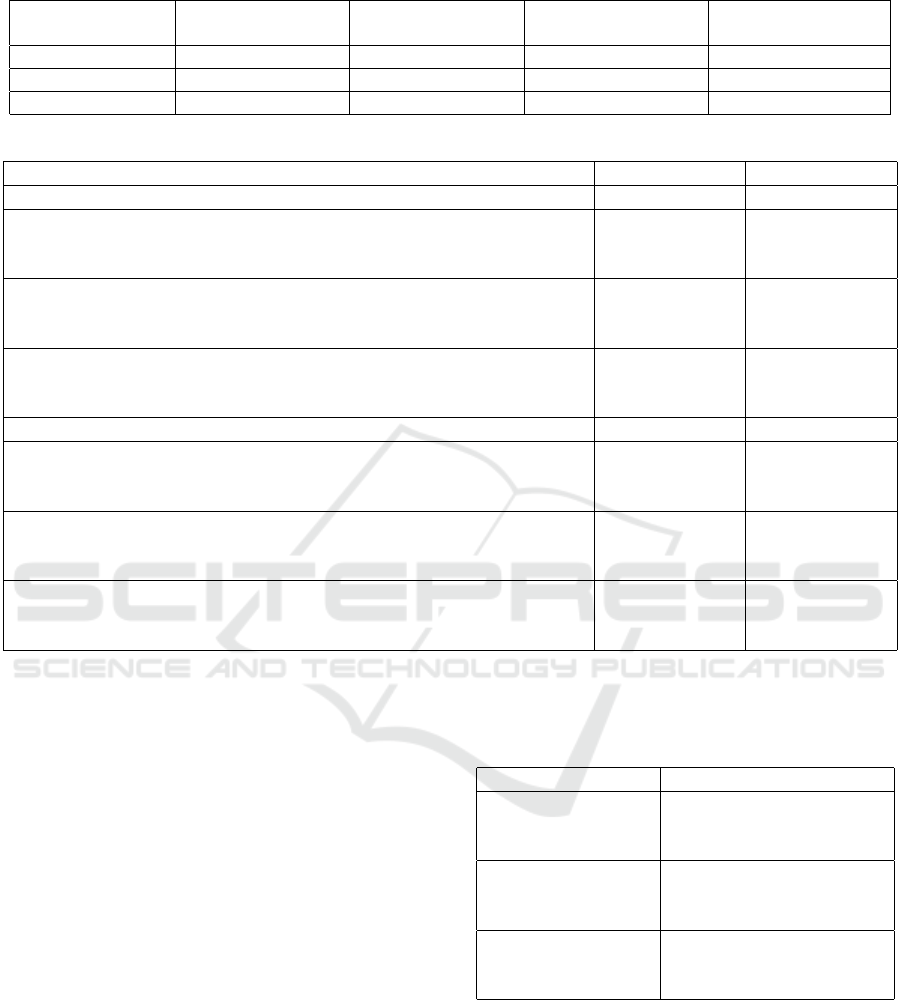

Figure 1: Visualization of the Relative Confidence Gain (RCG).

Figure 2: Comparison of difference measure with relative confidence gain analysis for module 1. Y-axis: relative confidence

gain or loss, X-axis: individual participants. (Values are ordered from low to high relative confidence gain (RCG).)

Relative Confidence Gain: The relative confidence gain (RCG) of the participant for module 1.

SCR Post Average: The result of a participant in the post module 1 SCR survey (average of the three questions per participant).

SCR Pre Post Difference: The difference between the average pre- and post-SCR survey results in module 1.

the learner had a loss in confidence. In comparison to

established models, like the normalized gain used by

Hake (Hake, 1998), the RCG also accounts for loss

in students’ perceived confidence, and uses individual

student values instead of the student average. See Fig-

ure 1 for a visualization of the RCG model, and Figure

2 for a course data graph which shows that the RCG

is more informative than the plain difference, particu-

larly for participants that started with a very high skill

confidence rating in the pre module survey, as it takes

the possible gain of experience into account.

6 RESULTS

6.1 Sample

9242 participants enrolled in the online course, of

which 4501 filled in the pre SCR for the first learning

module. For module 2, 1961 learners filled in the pre

survey and for the additional learning module (’ex-

cursus’), 1536 learners finished the pre SCR. In all

three pre-post SCR evaluations fewer learners filled in

the pre than the post survey. The cleaned and merged

dataset per module offered a sample of n = 1689 for

module 1 and n = 1147 for module 2. The cleaned

and merged dataset across all modules excluding the

excursus left a sample of n = 920. Since the group

work content of module 3 differed significantly from

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

536

the individual work content of the first two models,

we only considered the SCR results of module 1 and

2 in our results section for this paper. Table 1 shows

an overview of all sample sizes.

6.2 Frequency Distribution

Figure 3 to 8 show the distribution of participants’

pre and post ratings per question for both modules.

The graphs show that participants’ skill confidence

perception was on average higher in the post mod-

ule survey than in the pre module survey. With skill

confidence ratings for questions within a module and

means being similar (see Table 2), we will visualize

the average value of all questions or means per mod-

ule in other graphs.

Figure 3: Module 1, Question 1: Pre and Post Values.

Figure 4: Module 1, Question 2: Pre and Post Values.

6.3 Mean Distribution

Table 2 contains the mean comparison of SCR ratings

for all questions, showing an increase of means from

pre to post rating. Confidence intervals for the data

show a small range of data points between upper limit

and lower limit, indicating that it is possible to check

for both between-person effects and within-person ef-

fects. Table 2 also shows lower initial skill confidence

ratings for module 2 than for module 1. Initial con-

fidence values in module 1 ranged from 4.24 to 4.82;

Figure 5: Module 1, Question 3: Pre and Post Values.

Figure 6: Module 2, Question 1: Pre and Post Values.

Figure 7: Module 2, Question 2: Pre and Post Values.

Figure 8: Module 2, Question 3: Pre and Post Values.

whereas initial confidence values for module 2 ranged

Skill Confidence Ratings in a MOOC: Examining the Link between Skill Confidence and Learner Development

537

Table 1: Overview of sample sizes in pre and post SCR tests for all learning modules.

Learning module Pre Post merged per module merged across

module 1 and 2

1 N = 4501 N = 1962 N = 1689 N = 920

2 N = 1961 N = 1283 N = 1147 N = 920

Excursus N = 1536 N = 477 N = 427

Table 2: Mean comparison between pre and post SCR for all question items per module, in datasets merged per module.

Pre Post

Module 1

1. How confident do you feel to define and call methods in Java (before

and after Module 1)?

M = 4.69 (n =

1689), 95% CI

[4.68, 4.69]

M = 7.07 (n =

1689), 95% CI

[7.06, 7.07]

2. How confident do you feel to define and instantiate classes and ob-

jects (with State and Behavior) in Java (before and after Module 1)?

M = 4.24 (n =

1689), 95% CI

[4.23, 4.24]

M = 7.01 (n =

1689), 95% CI

[7.00, 7.01]

3. How confident do you feel in using control structures (such as con-

ditions and loops) in Java (before and after Module 1)?

M = 4.82 (n =

1689), 95% CI

[4.81, 4.82]

M = 7.1 (n =

1689), 95% CI

[7.16, 7.17]

Module 2

1. How confident do you feel in your understanding of the concepts

of inheritance and polymorphism. Are you confident to apply these

concepts (before and after Module 2)?

M = 3.45 (n =

1147), 95% CI

[3.45, 3.46]

M = 6.47 (n =

1147), 95% CI

[6.47, 6.48]

2. How confident do you feel to apply the concept of encapsulation

and use visibility modifiers in object-oriented programming (before and

after Module 2)?

M = 3.65 (n =

1147), 95% CI

[3.64, 3.65]

M = 6.93 (n =

1147), 95% CI

[6.92, 6.93]

3. How confident do you feel to use Java Collections (before and after

Module 2)?

M = 2.25 (n =

1147), 95% CI

[2.24, 2.25]

M = 5.73 (n =

1147), 95% CI

[5.72, 5.73]

from 2.25 to 3.65; on average 1,47 scale points below

module 1.

6.4 Learner Skill Confidence and

Learner Performance

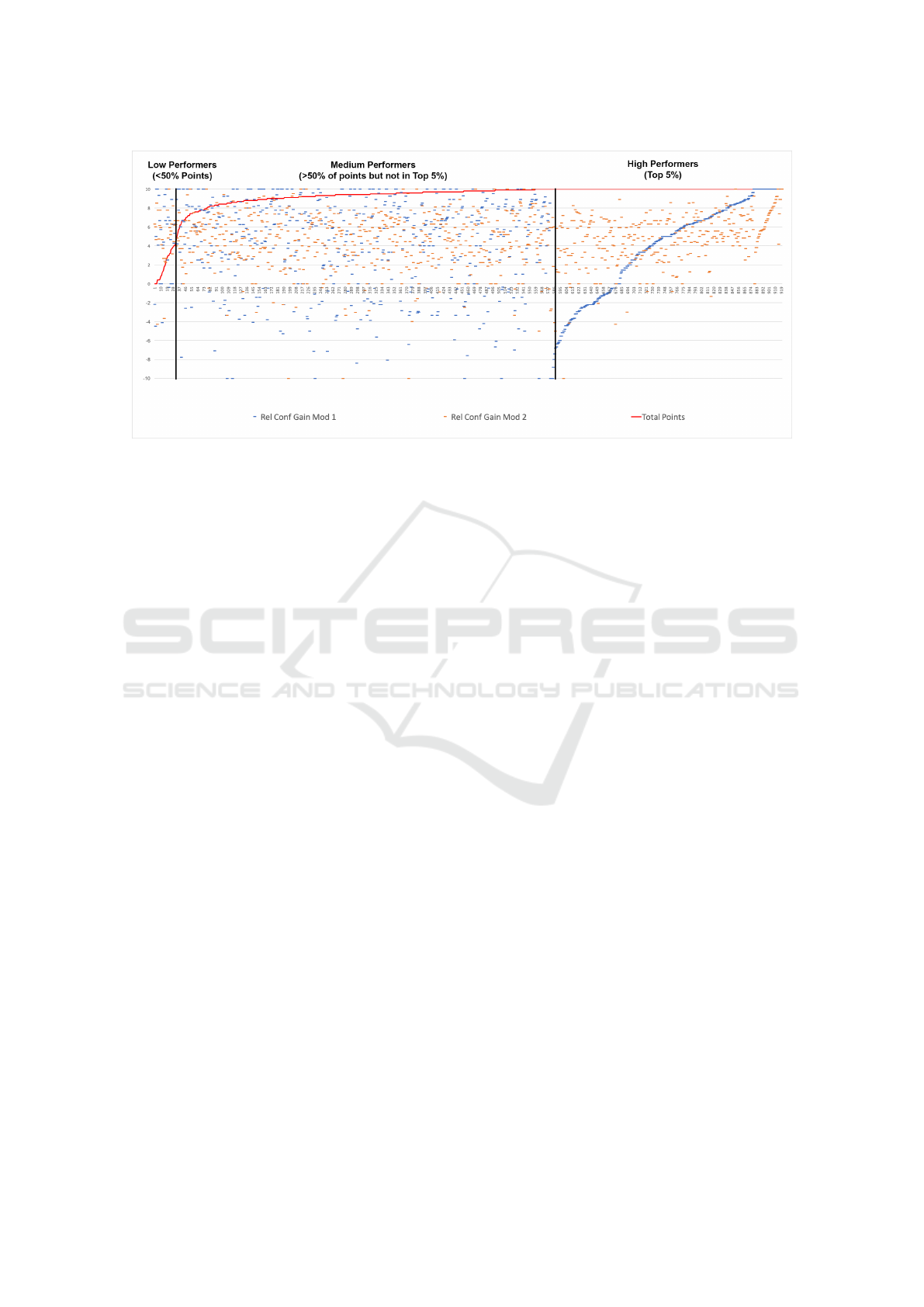

We looked at the relationship of learners’ relative con-

fidence gain (or loss) and their course points. Results

do not show a correlation between RCG and average

points reached: The correlation for RCG and aver-

age points in module 1 is r = -.06, with a p-value of

0.055; the correlation in module 2 is r = -.03789, with

a p-value of 0.025, which makes the correlation coef-

ficient statistically insignificant. Thereby, we cannot

prove a correlation between RCG and learner perfor-

mance. We consequently visualized the variables with

scatterplots, showing the trendlines for the respective

values (see 9). These suggest that there is no correla-

tion between the two variables. Furthermore, we visu-

alized different performance groups in the graph: low

performers, medium performers, and top performers

(categories based on the points gained in the course,

see Table 3). Likewise, results of learners in different

performance groups do not suggest correlation (see

Figure 9).

Table 3: Classification of Participant Performance.

Performance level Learner performance

Low performers less than 50% of total

course points (no certifi-

cate)

Medium performers more than 50% of total

course points, but not in

top 5%

Medium performers more than 50% of total

course points, but not in

top 5%

7 DISCUSSION

In the following, we discuss three main findings from

our results, which correspond to our research sub-

questions. When evaluating the SCR results for all

questions, we found a mean increase for all values

from pre to post rating. For module 1, confidence rat-

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

538

Figure 9: SCR and learner performance scatterplot. Y-axis: relative confidence gain or loss, X-axis: individual participants.

(Values are ordered by 1. Total Points; 2. Rel Conf Gain Week 1; 3. Rel Conf Gain Week 2) Rel Conf Gain Mod 1, 2: The

relative confidence gain for module 1 or 2 respectively. Total Points: The percentage points achieved by the participant in the

course.

ing means for each question increased more than 2.4

scale points on average. Ratings rose clearly for ques-

tion 2, describing the skill of ”defining and instantiat-

ing classes and objects”, with 2.77 scale points in dif-

ference. For module 2, means rose even more visibly:

3.2 scale points on average.

We assume that learners perceive an increase of

their skill confidence during the learning modules.

This might be due to the ongoing training experience

as such, or the satisfying quality of the learning con-

tent. Learners’ perception of their confidence may

also have changed due to course expectations or the

time that passed.

We found that initial skill confidence values were

on average lower for module 2 than for module 1.

This might be related to a shift in learners’ expecta-

tions of successfully finishing the first module. This

behavior would be in line with Bandura’s work on

self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977). Bandura argues that

confidence increases if the learner has a high ex-

pectancy of success, and decreases if the learners has

a low expectancy of success or fear of failure. Mod-

ules in this MOOC were blocks that build on one an-

other. The first module in this Object-Oriented Pro-

gramming in Java MOOC introduced learners to ba-

sic concepts with the goal of aligning novice, be-

ginner and more advanced learners. The topics of

the second module could be considered as more ad-

vanced. Learners who started the first module confi-

dently might have reduced their expectations after un-

derstanding the scope of the learning content, and thus

entered lower initial confidence ratings for the sec-

ond module in general. Furthermore, 304 participants

(33.04%) of the ’merged across all modules’ sample

stated ’expert’ or ’advanced’ skills in programming in

their platform profile. It is possible that these learn-

ers rated their initial skill confidence higher because

they were confident to succeed in the first module due

to their priorly acquired skills. Alternatively, learners

might have been familiar with the concepts of module

1 from prior experiences, but not with the concepts of

module 2. We assume that learners entered a lower

initial skill confidence rating for the second module

because they had a lower expectancy of success.

We could not find a correlation between learner skill

confidence and learner performance. Our findings did

not provide evidence for a relation between relative

confidence gain and performance outcome measures

(total points received). We thus need to explore this

issue further in upcoming research.

7.1 Implications

Our findings have different implications for the use of

the SCR survey in MOOCs. Firstly, the survey could

be used as a tool to assess if in general, learner confi-

dence with specific skills improves during the course.

Secondly, the survey could be used as a tool to assess

whether learners need more support in gaining a re-

alistic understanding of the tasks they are facing, and

whether they need additional help to adapt to the diffi-

culty. Both of these applications allow course instruc-

tors to intervene and react during the course if neces-

sary. Thirdly, we cannot draw any implications about

the survey’s use as a tool to correlate skill perception

and learner performance. To explore this further, we

Skill Confidence Ratings in a MOOC: Examining the Link between Skill Confidence and Learner Development

539

will conduct the survey repeatedly and explore rea-

sons for the (in)ability of learners to adequately as-

sess their skill level. We will also look into the pos-

sible effect of sources of self-efficacy as postulated

by Bandura, such as experiences of success or failure,

on the learner’s self-efficacy and resulting behavior

(Bandura, 1986), in between surveys, which may dif-

fer from their initial skill perception.

7.2 Limitations

Assessing learner (skill) confidence in surveys is a

challenging task: In a study with university students,

Dinsmore and Parkinson found that students’ confi-

dence ratings in a post-task survey include elements

on person and task characteristics, and often even

a combination of person and environment character-

istics (Dinsmore and Parkinson, 2013). Their data

proves that participants were taking into account mul-

tiple factors when rating their confidence. Their

findings reveal the problems in surveying confidence

ratings. While calibration focuses on the distance

between perceived and demonstrated levels of un-

derstanding, capability, competence, or preparedness

(Alexander, 2013) in comparison to our emphasis on

skill confidence, we will consider findings from the

discipline for our research, especially the scope of

calibration effects (Pieschl, 2009). In future vali-

dations and iterations of the skill confidence rating,

we will furthermore consider the possibility of using

other models of measuring (Dinsmore and Parkinson,

2013).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank the course designers and instructors of our

case MOOC and the platform team.

REFERENCES

Alexander, P. A. (2013). Calibration: What is it and why it

matters? an introduction to the special issue on cali-

brating calibration. Learning and Instruction, 24:1–3.

Annett, J. (1989). Training skilled performance. Acquisition

and performance of cognitive skills, pages 61–84.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social Learning Theory. Prentice Hall

series in social learning theory. Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundation of thought and ac-

tion: A social-cognitive view. Englewood Cliffs.

Bandura, A. (2006). Guide for constructing self-efficacy

scales. Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents, 5(1):307–

337.

Bell, B. S. and Kozlowski, S. W. (2010). Toward a the-

ory of learner-centered training design: An integrative

framework of active learning. Learning, training, and

development in organizations, pages 263–300.

Dinsmore, D. L. and Parkinson, M. M. (2013). What are

confidence judgments made of? Students’ explana-

tions for their confidence ratings and what that means

for calibration. Learning and Instruction, 24:4–14.

Dreyfus, S. E. (2004). The five-stage model of adult skill

acquisition. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Soci-

ety, 24(3):177–181.

Dreyfus, S. E. and Dreyfus, H. L. (1980). A five-stage

model of the mental activities involved in directed

skill acquisition. Technical report, California Univer-

sity Berkeley Operations Research Center.

Haggard, S. et al. (2013). The maturing of the MOOC. bis

research paper no. 130.

Hake, R. R. (1998). Interactive-engagement versus tra-

ditional methods: A six-thousand-student survey of

mechanics test data for introductory physics courses.

American Journal of Physics, 66(1):64–74.

Hood, N., Littlejohn, A., and Milligan, C. (2015). Context

counts: How learners’ contexts influence learning in a

MOOC. Computers & Education, 91:83–91.

Keller, J. and Suzuki, K. (2004). Learner motivation and e-

learning design: A multinationally validated process.

Journal of Educational Media, 29(3):229–239.

Keller, J. M. (1987). Strategies for stimulating the motiva-

tion to learn. Performance Improvement, 26(8):1–7.

Mackness, J., Mak, S., and Williams, R. (2010). The ideals

and reality of participating in a MOOC. In Proceed-

ings of the 7th International Conference on Networked

Learning. University of Lancaster.

Martin, R. L. (2009). The design of business: Why design

thinking is the next competitive advantage. Harvard

Business Press.

Moller, L. A. (1993). The effects of confidence building

strategies on learner motivation and achievement.

Pieschl, S. (2009). Metacognitive calibration—an ex-

tended conceptualization and potential applications.

Metacognition and Learning, 4(1):3–31.

Salas, E., Tannenbaum, S. I., Kraiger, K., and Smith-

Jentsch, K. A. (2012). The science of training and de-

velopment in organizations: What matters in practice.

Psychological science in the public interest, 13(2):74–

101.

Taheri, M., Mayer, L., von Schmieden, K., and Meinel, C.

(2018). The DT MOOC prototype: Towards teaching

design thinking at scale. In Design Thinking Research,

pages 217–237. Springer.

Usher, E. L. and Pajares, F. (2008). Self-efficacy for self-

regulated learning: A validation study. Educational

and Psychological Measurement, 68(3):443–463.

Weiner, B. (1974). Achievement motivation and attribution

theory. General Learning Press.

Yuan, L. and Powell, S. (2013). MOOCs and open educa-

tion: Implications for higher education.

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

540