Guidelines for Integrating Social and Ethical User Requirements in

Lifelogging Technology Development

Julia Offermann-van Heek, Wiktoria Wilkowska, Philipp Brauner and Martina Ziefle

Human-Computer Interaction Center, RWTH Aachen University, Aachen, Germany

Keywords: Technology Acceptance, Lifelogging Technology, Ethics, User Diversity, Guidelines.

Abstract: Lifelogging technologies have the potential to facilitate and enrich the everyday life of younger as well as

older people. On the one hand, tracking and logging of data about activities and behavior support an active

lifestyle. On the other hand, tracking medical data and movements support increasing safety by detecting,

e.g., emergencies or falls. From a technical perspective, a variety of technologies enable lifelogging and are

already available on the market. Instead, there is very little knowledge about the perception and acceptance

of lifelogging technologies from users’ socio-ethical perspective. Hence, this paper presents research results

from four online survey studies (n = 1107) aiming at covering a broad range of lifelogging applications and

reaching diverse target groups. Being based on insights gathered from the quantitative data collection, this

paper derives guidelines for integrating ethical and social perspectives in lifelogging technology development

and emphasizes gaps within the research landscape regarding its perception and acceptance.

1 INTRODUCTION

Demographic developments along with increasing

proportions of older people in need of care pose tre-

mendous social, political, and economic challenges

for today’s society and its care sectors (Pickard, 2015;

Bloom and Canning, 2004; Walker and Maltby,

2012). For example, Germany is one of the countries

representing strong demographic change develop-

ments resulting in 21% of the population aged above

65 years and 11% aged above 75 years in 2014

(Haustein et al., 2016). Decreasing proportions of

people who are able to pay and care for the increasing

proportions of older people aggravate this problem-

atic development. Although, 64% of people beyond

90 years of age are in need of intensive care (Haustein

et al., 2016), the majority of older people desires to

stay at home as long as possible, staying active and

living their life as independently and autonomously

as possible (Wilkowska and Ziefle, 2011).

The usage of lifelogging technologies represents

one approach to address and support the fulfillment

of these wishes. Also, such technologies (e.g., smart

watches, fitness trackers) have a preventive function

in motivating and supporting a healthier and more ac-

tive lifestyle for younger and older people likewise

(Lidynia et al., 2018). These diverse functions already

imply a very broad range of technologies that can be

used for lifelogging, e.g., differing between wearable

and non-wearable technologies, a single device and

complex smart home systems, or camera-based vs.

motion sensor-based systems (Rashidi and Mihai-

lidis, 2013; Bouma et al., 2007).

Since such systems intervene deeply in the auton-

omy of their users, it is necessary to consider ethical,

legal, and social aspects in addition to a solely tech-

nical perspective. Even if the implementation of a

technology is aligned with engineers, lawyers and

ethicists, its use can fail due to a mismatch between

the system and the social expectations, and thus, a

lack of social acceptance.

Consequently, this article presents users’ social

and ethical expectations of life-logging technologies

for different stakeholders and different usage con-

texts. The findings from our four studies inform about

which aspects are accepted and which are rejected.

Taking this knowledge into account, this research can

contribute to the development of accepted lifelogging

systems.

Heek, J., Wilkowska, W., Brauner, P. and Ziefle, M.

Guidelines for Integrating Social and Ethical User Requirements in Lifelogging Technology Development.

DOI: 10.5220/0007692900670079

In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2019), pages 67-79

ISBN: 978-989-758-368-1

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

67

2 PERCEPTION OF

LIFELOGGING TECHNOLOGY

In the following, the current state of the art is pre-

sented starting with a short technical overview of life-

logging, followed by research on users’ perception of

lifelogging technologies. Finally, the related research

project of the current studies and the underlying re-

search questions are detailed.

2.1 Lifelogging Applications

Commonly, the term lifelogging relates to different

types of digital self-tracking and recording of every-

day life. It is often interchangeably used with self-

tracking or quantified self (QS) (Selke, 2016; Gurrin

et al., 2014a). In general, lifelogging is understood as

capturing human life in real time by recording physi-

ological as well as behavioral data, whereas by stor-

age of data, self-archiving, self-observation, and self-

reflection are enabled. Thus, lifelogging represents a

phenomenon whereby people can digitally record

their own daily lives in varying amounts of detail, for

a variety of purposes (Gurrin et al., 2014b).

As there is no tight boundary, lifelogging is con-

nected to other research areas and can be seen as part

of Ambient Assisted Living (AAL) aiming for activ-

ity monitoring, recognition of abnormal behavior, re-

minding, detection of emergencies, as well as sup-

porting and facilitating everyday life (Rashidi and

Mihailidis, 2013). Within the context of AAL, diverse

technologies and sensors used for lifelogging reach

from ambient-installed to wearable configurations

and can be used in private environments, smart

homes, as well as in professional care institutions for

old and frail people (e.g., Jalal et al., 2014). In this

way, collection, processing, and analyzing of person-

related data can help to improve a longer independent

living and provides assistance for diverse stakehold-

ers (e.g., older and frail people, professional caregiv-

ers, relatives of people in need of care, etc.).

The spectrum of single lifelogging applications is

extremely broad, reaching from assisting technology

devices for older people to sportive devices mainly

used by younger people during their leisure time. To

mention some technology examples, health and mon-

itoring tools aim for monitoring of single activities

and movements (Nambu and Masayuki, 2005), rec-

ognizing social activity (Wang et al., 2009), identify-

ing changes in movements or behaviors as indicators

for dementia (Hayes et al., 2008), or enabling fall de-

tection (Shi et al., 2009). Instead, sportive technology

applications aim for tracking and improving of phys-

ical activity, nutrition, and gamification (e.g.,

Schoeppe et al., 2016). Besides technical opportuni-

ties, functions, and feasibility, the users’ perception

and acceptance of those technologies is essential.

2.2 Users’ Perceptions of Lifelogging

With regard to a social perspective, lifelogging tech-

nologies are overall seen as a possible solution for the

challenges of demographic change, are mostly per-

ceived and evaluated positively, and the necessity and

usefulness of technical support are highly acknowl-

edged (Beringer et al., 2011; Gvercin et al., 2016).

Within the perception of benefits of using assisting

technologies, the opportunity of staying longer at the

own home and an independent life are strong motives

to use (or imagine using) assisting lifelogging tech-

nologies especially with regard to older adults and ag-

ing in place. In particular, a reminding function is fre-

quently confirmed as a reason for creating a lifelog by

different stakeholders (i.e., older and younger adults

as well as children likewise) (Morganti et al., 2013;

Gall et al., 2016). Apart from these functions, when

asking older people about potential benefits of life-

logging technologies, also safety-related benefits

(e.g., alarms, fall detection) are of major importance

(Schomakers et al., 2018; Biermann et al., 2018).

Sharing and collecting information with people - in

specific the family circle - (Caprani et al., 2013;

Caprani et al., 2014) represents a further specific mo-

tivation to use lifelogging technologies. On the other

hand, restraints and acceptance barriers such as feel-

ings of isolation (e.g., Sun et al., 2010), feelings of

surveillance, and invasion of privacy (e.g., Wilkow-

ska et al., 2015) were frequently mentioned when ask-

ing people to think about using lifelogging technolo-

gies in their everyday life. In more detail, a perceived

loss of control over sensitive data or unauthorized for-

warding to third parties are great barriers for using

life-logging applications (Lidynia et al., 2018).

Theories of technology acceptance have mainly

focused on the two key components, perceived use-

fulness and perceived ease of use, so far. But studies

have shown, that additional motives and barriers play

a crucial role in the context of assistive technologies

for older adults (e.g., Jaschinski and Allouch, 2015;

Peek et al., 2014). Frequently, AAL technologies are

designed to operate in our homes and be close to our

bodies, are associated with negative aspects of aging,

illness, and even with surveillance. Thus, barriers re-

garding stigmatization, privacy, and usability are pre-

dominant. Studies show that users acknowledge the

potential of AAL technologies but are also concerned

because of barriers. Thus, trade-offs between per-

ICT4AWE 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

68

ceived benefits and barriers are crucial for the ac-

ceptance of AAL technologies (van Heek et al.,

2017a,b). Besides potential and perceived benefits

and barriers, the type of technology (Himmel and

Ziefle, 2016) and application context (van Heek et al.,

2016) have been proven to impact acceptance pat-

terns. Further, previous research has identified age

and gender (Wilkowska and Ziefle, 2011), health sta-

tus (Klack et al., 2011), and professional care experi-

ence (Peek et al., 2014) to be impacting user diversity

factors for the acceptance of assisting and lifelogging

technologies.

In contrast to social perspectives on lifelogging

technology usage, there are only few studies focusing

empirically on user-related ethical issues of using

lifelogging technologies in diverse contexts. Within

ethical considerations, a user-oriented structuring and

preservation of personal privacy of the lifelogging

technology users represents one of the most challeng-

ing tasks (Jacquemard et al., 2014). Some studies em-

phasize the importance of asking the legitimate and

ethical questions related to sharing, ownership, and

security of data (e.g., Wolf et al., 2014): In more de-

tail, people want to know which data is tracked, when

data is tracked, what happens to tracked data, and who

has access to tracked or logged data. Other studies

provide first ethical frameworks for specific types of

technologies focusing on privacy, data handling, and

provided information, e.g., wearable cameras (Kelly

et al., 2013). Beyond privacy-related aspects, ethical

considerations start even earlier asking for what are

lifelogging technologies generally allowed to do or

who has the right to make decisions referring to tech-

nology usage. So far, there has been hardly any re-

search on a general ethical framework for a broad

range of lifelogging technologies, diverse lifelogging

contexts and target groups. In addition, it is question-

able whether ethical requirements are influenced by

user factors playing a crucial role for users’ social

perception of lifelogging.

2.3 Project PAAL and Research Aims

Parts of the European research project PAAL (Pri-

vacy Aware and Acceptable Lifelogging services for

older and frail people) address exactly this gap by

providing an empirically derived, user-related socio-

ethical framework for lifelogging technology devel-

opment. On this basis, privacy-aware lifelogging

technologies will be developed and evaluated in the

future project progression. To provide a framework

for a broad spectrum of lifelogging technologies, ful-

filling social and ethical perspectives, an empirical

approach is necessary investigating diverse lifelog-

ging contexts, diverse target groups of lifelogging us-

ers, and in particular their ethical and privacy-related

concerns referring to lifelogging technology usage.

Hence, the underlying research questions aim for an

investigation whether the social perception of lifelog-

ging technologies, their benefits and barriers depend

on the lifelogging context and on user factors. Fur-

ther, it will be analyzed in detail how diverse users

perceive ethically relevant aspects of lifelogging

technology usage and whether the ethical perception

of data handling (e.g., data types, ways of handling,

data access) depend on the lifelogging context. An-

swering these research questions will then provide the

basis to derive guidelines for considering ethically

and socially relevant issues in lifelogging technology

development.

3 METHODOLOGY

This section presents the methodical approach of the

study, starting with the empirical concept, followed

by short descriptions of the conducted studies and

their respective samples.

3.1 Research Approach

Beyond normative legal and ethical considerations,

the current research approach aimed for an empirical

exploration of socially and ethically relevant aspects

for lifelogging from the user’s perspective. In order to

answer open research questions in regarding user-re-

lated socio-ethical requirements for a broad spectrum

of lifelogging technology development, four different

quantitative studies were conducted. Each of the stud-

ies had another thematic context and a specific target

group: sportive, medical home, caregivers, and aging

and health. The target groups reached from healthy

young adults, middle-aged adults, middle-aged pro-

fessional caregivers to a large sample of adults of all

ages having experiences with chronic diseases and

care.

All quantitative studies are based on preceding

qualitative studies (interviews and focus groups).

Overall, four online surveys were conducted reaching

a total of N = 1107 participants in Germany.

3.2 Empirical Studies – Design

Each of the studies presented here is based on a spe-

cific qualitative preceding study enabling the concep-

Guidelines for Integrating Social and Ethical User Requirements in Lifelogging Technology Development

69

tualization of the respective quantitative online sur-

vey study. A short overview of the single studies’

concepts and sample is presented in the following.

3.2.1 Study 1: Sportive Lifelogging

The first study aimed for an investigation of young

adults’ perceptions of lifelogging technologies in a

sportive usage context.

Online Survey. Following a short introduction into

the topic of lifelogging technologies for leisure appli-

cations (e.g., sports and health monitoring), the par-

ticipants were asked for demographic information.

Afterwards, attitudinal characteristics such as the par-

ticipants’ attitudes towards technology (5 items; =

.857) and their perceived needs for privacy (3 items;

= .778) were assessed. Among others, the partici-

pants were then asked to evaluate a) potential benefits

(11 items; = .873) and barriers (16 items; = .899)

of lifelogging technology usage, b) their acceptance

of lifelogging technology usage (3 items; = .929),

and c) which information should be tracked by life-

logging technologies (17 items). Finally, the partici-

pants also assessed diverse options to realize lifelog-

ging technology (17 items) and different applications

contexts of lifelogging technology usage (17 items).

Sample. Overall, N = 169 participants completed the

online questionnaire in summer 2018. The mean age

of the participants was 35.3 years (SD = 14.1; min =

15; max = 69) with 56.8% (n = 96) females and 43.2%

males (n = 73). The educational level of the partici-

pants was high with 48.8% holding a university de-

gree and 35.5% a university entrance diploma. Fur-

ther, 10.2% reported a completed apprenticeship as

highest educational level, while 5.4% hold a second-

ary school certificate or had no degree (yet). 19.3% (n

= 33) of the participants indicated to suffer from a

chronic illness. Considering attitudinal characteris-

tics, the participants indicated to have a rather posi-

tive attitude towards technology (M = 3.8; SD = 1.1;

min = 1; max = 6) and they classified their needs for

privacy as rather high (M = 4.1; SD = 1.1; min = 1;

max = 6).

3.2.2 Study 2: Medical Lifelogging at Home

The second study aimed at an analysis of middle-aged

persons’ perception of medical lifelogging technol-

ogy usage at home. Two focus groups provided the

basis to conceptualize the quantitative study.

Online Survey. The participants indicated demo-

graphic information after a short introduction into the

topic of using lifelogging technologies for monitoring

(e.g., vital parameters) and reminding (e.g., intake of

medicine) at home. Further, they reported if they suf-

fer from a chronic illness or depend on care. Subse-

quently, the participants indicated previous experi-

ences with care (e.g., family member in need of care).

Referring to attitudinal characteristics, the partici-

pants evaluated their attitude towards technology (5

items; = .873). As technology-related aspects, the

participants assessed potential benefits (5 items; =

.873) and barriers (5 items; = .873) of lifelogging

technology usage as well as acceptance (5 items; =

.873). Further, the participants also evaluated specific

functions lifelogging technologies should fulfil (5

items; = .873). From an ethical perspective, the

participants were asked to evaluate aspects lifelog-

ging technologies were allowed (5 items; = .873)

and were NOT allowed to do (5 items; = .873).

Sample. A total of N = 195 respondents participated

in the online survey and supplied all required infor-

mation in September 2018. The participants were on

average 41.7 years old (SD = 14.7; min = 16; max =

71) with 65.1% females (34.9% males). The educa-

tional level was rather high with 41.5% of the partic-

ipants holding a university degree and 19.0% a uni-

versity entrance diploma. In addition, 28.2% indi-

cated to complete an apprenticeship and 11.3% sec-

ondary school. Referring to health- and care-related

issues, 32.3% (n = 63) of the participants indicated to

suffer from a chronic illness, while only 2.1% (n = 4)

reported to depend on care. Further, 24.1% (n = 47)

reported to have professional care experience. Con-

cerning private experience in care, 52.8% (n = 103)

indicated to have a family member in need of care,

while 41.0% (n = 80) have already been a caregiver

for a family member in need of care.

3.2.3 Study 3: Caregivers and Lifelogging

A further study specifically focused on professional

caregivers’ perception of lifelogging technologies in

care contexts and focused on data security and pri-

vacy issues (van Heek et al., 2018).

Online Survey. The online survey started with asking

the participants for demographic information. Subse-

quently, the participants evaluated their needs for pri-

vacy (6 items; = .883) as well as their attitude to-

wards technology (4 items; = .884). All participants

had professional experience in working as caregivers

in the areas geriatric care, medical care, and care of

people with disabilities. Evaluating lifelogging tech-

nologies for monitoring and safety reasons in profes-

sional care contexts, the participants assessed poten-

tial benefits (14 items; = .923), barriers (17 items;

= .944), and acceptance of lifelogging technologies

ICT4AWE 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

70

(6 items; = .932). Focusing on data security and pri-

vacy aspects, the participants evaluated which types

of information (14 items; = .856) they allow to be

gathered by lifelogging technologies as well as con-

ditions of data storage (3 items; = .760) and data

access (3 items; = .802).

Sample. Overall, N = 170 completed the online sur-

vey in summer 2017 and fulfilled the condition to

have relevant experience in working as a professional

caregiver. The participants were on average 36.3

years old (SD = 11.2; min = 19; max = 68) with 74.7%

females (n = 127). The educational levels were me-

dium with the majority of participants holding a com-

pleted apprenticeship as highest degree. Further,

23.0% hold a university degree or a university en-

trance diploma, whole 11.8% completed secondary

school or had a comparable degree. With regard to at-

titudinal characteristics, the participants indicated a

medium attitude towards technology (M = 3.4; SD =

0.7; min = 1; max = 6) and rather high needs for pri-

vacy (M = 4.2; SD = 0.9; min = 1; max = 6).

3.2.4 Study 4: Lifelogging and Aging

A last study focused on a larger sample of adults of

all ages having different experience with chronic dis-

eases and care. This study aimed for an investigation

of ethically relevant aspects in the context of aging

and usage of lifelogging technologies.

Online Survey. First, the participants indicated de-

mographic information which provided the basis for

a census representative selection of the sample re-

garding age and gender. Further, the participants eval-

uated their attitudes towards technology (4 items; =

.842). Subsequent to a short introduction into the

topic of lifelogging technologies and their opportuni-

ties for aging in place, the participants assessed dif-

ferent benefits (14 items; = .957) and barriers of

technology usage (15 items; = .953) as well as their

acceptance of lifelogging technologies (3 items; =

.761) referring to different health scenarios. In addi-

tion, the study had an ethical focus asking for evalua-

tions of life-end-decisions and who is allowed to de-

cide in critical situations.

Sample. A total of N = 573 participants completed

the online survey in spring 2018. The mean age of the

participants was 48.3 years old (SD = 16.6; min = 20;

max = 85). 13.6% (n = 78) of the participants were

younger than 25 years, 29.5% (n = 169) were between

26 and 45 years, 30.7% (n = 176) between 46 and 60

years, and 26.2% (n = 150) were older than 60 years.

Gender was almost equally spread (47.8% females, n

= 274; 52.2% males, n = 299). The highest educa-

tional level was completely mixed: 36.0% completed

an apprenticeship, 21.6% hold a university degree,

19.2% a university entrance diploma, and 23.2% di-

verse secondary school certificates. With regard to

health- and care-related issues, 61.3% of the partici-

pants (n = 351) indicated to suffer from a chronic ill-

ness and 11.4% (n = 65) reported to depend on care

in their everyday life. Among the indicated chronic

illnesses, typical age-related illnesses (e.g., diabetes,

high blood pressure, arthrosis, back pain due to

slipped disc) were mentioned nearly as often as age-

independent illnesses (e.g., multiple sclerosis, depres-

sions, epilepsy). Referring to attitudinal characteris-

tics, the participants’ attitude towards technology was

on average rather positive (M = 4.4; SD = 1.1; min =

1; max = 6).

4 RESULTS

The four studies aimed at answering the research

questions introduced in section 2.3. In the following,

the research questions are answered starting with rel-

evant aspects belonging to the social perspective on

lifelogging technologies. Afterwards, a focus on eth-

ically relevant aspects provides detailed insights into

data security and privacy-related evaluations of di-

verse user groups. Besides descriptive data analyses,

correlation, regression, and inferential statistical anal-

yses were applied. Whiskers within the diagrams of

the results section indicate the standard deviations.

4.1 Social Insights

Regarding socially relevant aspects of lifelogging

technologies, their perception and acceptance are fo-

cused on exploring perceived benefits and barriers of

technology usage and impacting user factors.

4.1.1 Social Perception of Lifelogging

Taking all studies into account (N = 1107), step-wise

linear regression analyses revealed that 49.4% (adj. r

2

= .494) variance of general acceptance of lifelogging

technology usage was explained by perceived bene-

fits ( = .547) and perceived barriers ( = -.312). Ac-

cording to that, the use is driven rather by perceived

benefits than by barriers. To gain deeper insights into

the importance of single benefits and barriers, step-

wise linear regression analyses were conducted for

each study.

Within the sportive usage context (n = 169), a fi-

nal regression model showed that 55.6% (adj. r

2

=

.556) variance of lifelogging technology acceptance

was explained by five specific benefits and barriers:

Guidelines for Integrating Social and Ethical User Requirements in Lifelogging Technology Development

71

increased life quality ( = .288), comfort ( = .199),

increased mobility ( = .206), feeling to be not able

to control the technology ( = -.270), and feeling of

being controlled ( = -.178).

In contrast, in the professional care context study

a lower percentage of variance of lifelogging technol-

ogy acceptance was explained, being based on four

different specific benefits and barriers (n = 170): here,

38.9% (adj. r

2

= .389) were explained by relief in pro-

fessional everyday life ( = .298), increased auton-

omy (for patients) ( = .241), fear of replacing human

care by technology ( = -.186), and fear of a complex

technology handling ( = -.174).

Similar results were found within the regression

analysis of older participants’ perceptions of lifelog-

ging technologies in the context of medical monitor-

ing at home (n = 195). Here, a higher percentage of

lifelogging technology acceptance’ variance (46.7%,

adj. r

2

= .467) could be explained by the benefits relief

in everyday life ( = .171), increased autonomy ( =

.234), increased feeling of safety ( = .181) and by

the barriers invasion of privacy ( = -.244) and fear

of replacing human care by technology ( = -.150).

Asking in particular older participants, who are

experienced with illnesses and care (n = 573) revealed

partly similar results: 42.0% of technology ac-

ceptance’ variance were explained by the perceived

benefits increased feeling of safety ( = .429), relief

in everyday life ( = .121), increased autonomy ( =

.117), and the perceived barrier invasion of privacy (

= -.161).

4.1.2 Realization of Lifelogging

The realization of lifelogging technologies and their

specific functions represented a further element of

some of the conducted studies.

Within the sportive usage context (n = 169), the

participants evaluated (well-known) smart watches as

best option of realizing lifelogging technologies.

Health-related functions and applications were most

desired – emergency detection, reminding functions

(e.g., medicine, nutrition), control of health and activ-

ity –, while applications supporting social interaction

or control of working progress were rather rejected.

With regard to professional care applications (n =

170), professional caregivers evaluated also already

used and well-known technologies as most suitable:

emergency buttons. Further, fall sensors, room sen-

sors, or motion sensors were also accepted as options

of lifelogging in professional environments. In con-

trast, audio- and video-based realizations of lifelog-

ging technologies were clearly not desired.

4.1.3 Impact of User Diversity

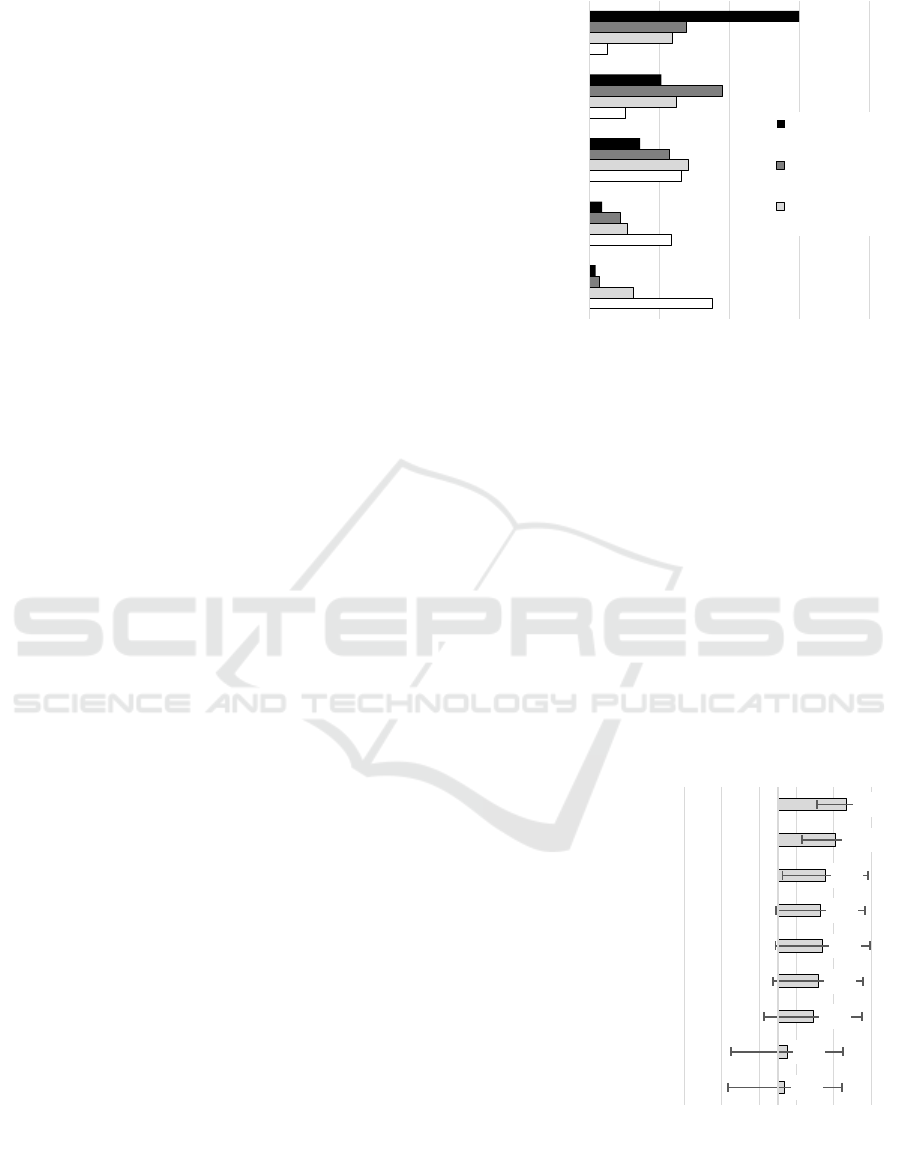

As illustrated in Figure 1, all studies were analyzed

for potential relationships between lifelogging tech-

nology perception and user factors (N = 1107).

First of all, the results revealed strong relation-

ships between lifelogging technology acceptance and

perceived benefits as well as perceived barriers. Fur-

ther, the acceptance of lifelogging technologies cor-

related with all investigated user factors.

Figure 1: Correlations of demographic factors and social perception and acceptance of lifelogging technologies (n = 1107).

Acceptance of

lifelogging technologies

Perceived benefits

Perceived barriers

Age

Gender

(1 = female; 2 = male)

Chronic illness

(1 = yes; 2 = no)

Professional care

experience

(1 = yes; 2 = no)

.638**

-.472**

.113**

-.199**

.118**

.150**

-.227**

-.201**

.146**

.186**

.223**

-.212**

-.264**

ICT4AWE 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

72

In particular, older participants tend to accept life-

logging technologies and acknowledge potential ben-

efits more than younger people, while there was a

negative correlation between age and the perception

of barriers. Regarding gender, the results indicate that

men were more inclined to accept lifelogging technol-

ogies than women, while women see higher barriers

of lifelogging technologies. Considering experience

with a chronic illness, people who suffer from a

chronic illness tend to accept lifelogging technologies

and their potential benefits more than healthy partici-

pants. Instead, healthy participants showed to higher

evaluations of potential lifelogging technology barri-

ers. Taking professional care experience into account,

professional caregivers were characterized by a lower

acceptance and lower evaluation of lifelogging tech-

nology benefits, while they showed a higher evalua-

tion of potential barriers compared to participants

without professional care experience. Summarizing,

acceptance increases with demand through age or ill-

ness.

These relationships give rise to the necessity to

analyze ethically relevant aspects (i.e., ethics- and

barrier-related issues such as privacy and data secu-

rity) in more depth and for diverse lifelogging con-

texts.

4.2 Ethical Insights

This section represents results referring to user-re-

lated ethical requirements for using lifelogging tech-

nology. Thereby, aspects like data access, data han-

dling, and decision-making are focused.

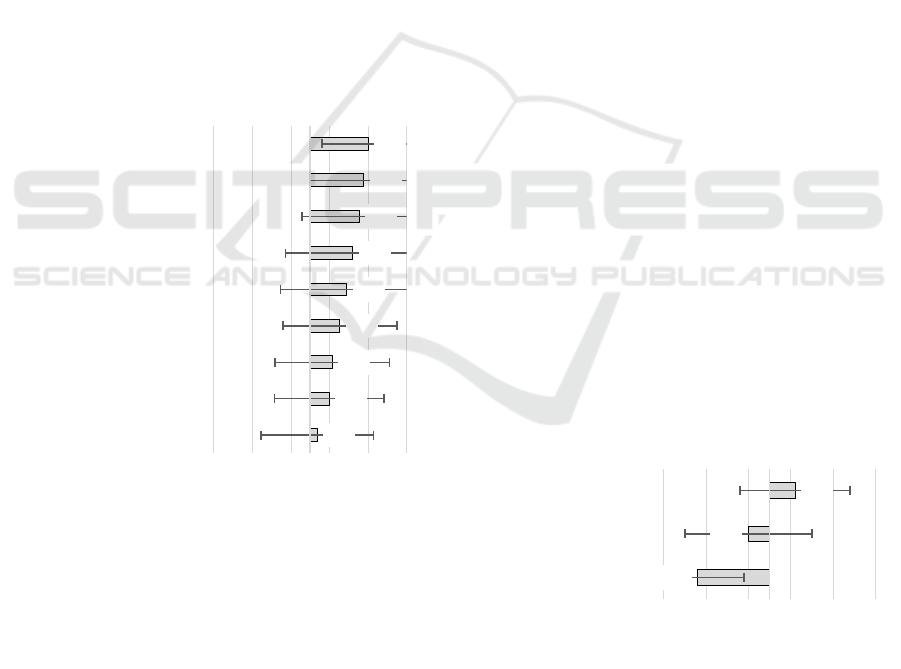

4.2.1 Which Data May be Gathered?

In study 1 (N = 169), predominantly young partici-

pants were asked to indicate which information they

want to track using lifelogging technology (Figure 2).

The most frequently mentioned information referred

to tracking of vital parameters, sleep, and nutrition.

Daily steps and travels were also mentioned fre-

quently. Besides further health-related information

such as weight or burned calories, also other areas

like tracking of finances, hobbies, or exposure of time

were indicated. Compared to that, aspects like track-

ing of number of spoken words, places, creative ideas,

or mood were mentioned occasionally.

Asking professional caregivers for their opinion

which information is allowed to be gathered in their

professional everyday life, clear statements were

found (n = 170) (van Heek et al., 2018): Within pro-

fessional care contexts, they clearly agree with track-

ing of emergency-related information, e.g., actuation

Figure 2: Mentioned information being allowed to be gath-

ered using lifelogging technologies (n = 169).

of emergency buttons or recordings of cries for help.

Further, the professional caregivers also accepted to

track room data enabling smart home functions, such

as automated doors and windows. Tracking of pa-

tients’ position was merely tolerated, while tracking

of the caregivers’ position was strictly rejected – alt-

hough the potential benefits of knowing the positions

of colleagues for fast support were acknowledged. Fi-

nally, the use of microphones or video-based technol-

ogies to track care-related information, such as dura-

tion of care, times at which rooms are entered or left,

or talks during care, were strongly rejected.

4.2.2 How Should Data be Handled?

The way of data handling was also evaluated in study

3 (Figure 3). Independent from the type of data, the

participants were only willing to accept data to be

evaluated for the moment. Storage on a daily basis or

long-term storage was most likely accepted for room

data, while it was clearly rejected for more privacy-

intensive data such as position, audio, and video data.

Figure 3: Evaluation of data handling (n = 170).

1.0 2.0 3.0 4.0 5.0 6.0

allowed to be only

evaluated for the moment

allowed to be stored on a

daily basis

allowed to be stored long-

term

evaluation (min = 1; max = 6)

rejection agreement

room data

position

data

audio data

video data

Guidelines for Integrating Social and Ethical User Requirements in Lifelogging Technology Development

73

In interviews with some of the participants of this

study it became clear that the willingness of data stor-

age increased with a deeper understanding of the ad-

vantages of data storage compared to data processing

(e.g., enabling detailed health analysis, movement

analyses). Hence, more detailed information about

data storage and its related characteristics led to ac-

ceptance of – at least – short-term storage of health-

related data. Correlation analyses revealed that those

evaluations were not related with user factors, such as

age, gender, or duration of care expertise.

4.2.3 Who is in Control? Who Owns Data?

In diverse studies, the participants were asked for

their opinions on who is allowed to access personal

data, when using lifelogging technologies. In profes-

sional care contexts (study 3, n = 170), personal data

was neither allowed to be accessible for colleagues

(M = 2.9; SD = 1.2), nor direct supervisors (M = 2.9;

SD = 1.3), and in particular not for all supervisors (M

= 2.5; SD = 1.2). Correlation results revealed that de-

mographic characteristics of the professional caregiv-

ers did not affect these results. In contrast, a tendency

was observable that position and room data were

more likely to be accessible for colleagues and super-

visors than audio and video data.

In the fourth study, participants were asked, who

is allowed to make decisions in severe health situa-

tions (Figure 4). The majority of the participants

(59.8%) indicated to want to decide totally them-

selves. Smaller proportions want that the doctor

(27.6%) or their immediate family (23.6%) decide. In

contrast, the participants did clearly not want that

other relatives had decision-making power (5.1%).

Further, the selections show that doctors are accepted

to decide largely by 38.0% of the participants.

The evaluation pattern of “not at all allowed to de-

cide” confirms that other relatives are not accepted to

make health decisions (35.0%), followed by the im-

mediate family (12.6%). To decide “not at all” for

themselves (1.7%) and decisions by doctors (2.8%)

received the lowest selections. Here, correlation anal-

yses revealed influences of age referring to the selec-

tion of “myself” (r = .222; p < .01) and my “relatives”

(r = -.129; p < .01) are allowed to decide: the results

indicate that older adults were more inclined to decide

“themselves” and expressed more strongly not to

want their “relatives” to decide compared to younger

participants.

Figure 4: Participants’ selections (n = 573) who is allowed

to decide (and to what extent) in severe health situations.

4.2.4 Do’s and Don’t’s of Lifelogging?

Figures 5 and 6 show the results of the participants’

evaluation of allowed and not allowed functions of

lifelogging technologies (study 2).

As shown in Figure 5, lifelogging and monitoring

technologies are highly desired to be used for func-

tions of reminding (M = 5.3; SD = 0.8) or supporting

in everyday life (M = 5.0; SD = 0.9). Functions like

recognition of languages and gestures (M = 4.8; SD =

1.1), fingerprints (M = 4.7; SD = 1.3), medical moni-

toring (M = 4.6; SD = 1.2), and storage of data (M =

4.4; SD = 1.3) were also allowed. In contrast, there

Figure 5: Evaluation of allowed functions of lifelogging

technologies.

35.0

23.5

26.2

10.2

5.1

12.6

10.7

28.2

24.9

23.6

2.8

8.7

22.9

38.0

27.6

1.7

3.6

14.4

20.5

59.8

0 20 40 60 80

not at all (0%)

a little (25%)

partly (50%)

largely (75%)

totally (100%)

selection in procent (%)

"myself"

"doctor"

"immediate

family"

3.7

3.7

4.4

4.6

4.7

4.6

4.8

5.0

5.3

1 2 3 4 5 6

Complement social contacts

Video surveillance (in the

house)

Storage of data when data is

encrypted

Monitoring (measurement,

recording of a process)

Recognition of fingerprints

Video surveillance (outside

the own house)

Recognition of language and

gestures

Support or help

Reminder (intake of

medicine, appointments)

evaluation (min=1; max=6)

rejection affirmation

What is lifelogging technology allowed to do?

ICT4AWE 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

74

was no clear agreement to use technology to comple-

ment social contact (neutral evaluations: M = 3.7; SD

= 1.5). Referring to the usage of video cameras, a

clear distinction between outdoor and indoor usage

was striking: while it was accepted outdoor (M = 4.6;

SD = 1.2), video cameras were clearly not wanted to

be used inside the own house (M = 3.7; SD = 1.5).

Referring to the functions the participants want

lifelogging technologies not to do, also a diverse eval-

uation pattern was striking (Figure 6). High agree-

ments of the participants show that they clearly do not

want to be dependent on a technology (M = 5.0; SD

= 1.2). Further, they do not want lifelogging technol-

ogies to make decisions independently (M = 4.9; SD

= 1.4). The evaluations show that – not surprisingly -

the technology should not fail (M = 4.8; SD = 1.5),

should not restrict the freedom of choice (M = 4.6;

SD = 1.7), nor taking over too much tasks (M = 4.3;

SD = 1.5) or substitute social contacts (M = 4.4; SD

= 1.7). Recording audio and video material (M = 3.7;

SD = 1.5) was slightly confirmed to be not allowed

by the technology.

Figure 6: Evaluation of NOT allowed functions of lifelog-

ging technologies.

Both ethical assessments of allowed and not al-

lowed technological functions were analyzed for in-

fluences of user diversity using correlation analyses.

Neither age, gender, suffering from a chronic illness,

nor care experience were related with the overall

evaluation of allowed and not allowed functions.

4.2.5 What about Life-end-decisions?

The probably most critical aspects within an ethical

perspective on technology use in health contexts meet

life-end-decisions. As optional questions, participants

were asked for their evaluation of technology use in

severe heath situations. In study 4, the question “Is

technology allowed to prolong life?” was confirmed

by 75.5% of the participants, while 24.5% of the par-

ticipants denied this question. Instead, the comple-

menting optional question “Is technology allowed to

delay death?” was affirmed by only 42.7% of the par-

ticipants, while 57.3% denied this question.

The second study confirmed these results by eval-

uations of two similar and one additional statement

(Figure 7). Here, the participants showed a slight

agreement referring the item “technology is allowed

to prolong life” (M = 4.1; SD = 1.3; min = 1; max =

6) and a slight rejection of “technology is allowed to

delay death“(M = 3.0; SD = 1.5; min = 1; max = 6).

In addition, the item “technology is allowed to decide

between life and death” (M = 1.8; SD = 1.1; min = 1;

max = 6) was clearly rejected by the participants.

Both studies were analyzed for influences of user

diversity on the evaluations. Yet, neither gender, suf-

fering from a chronic illness, nor care experience in-

fluenced these results. In contrast, correlations with

age were observable for both studies. In study 2 (r = -

.220, p < .01) and study 4 (r = -.140; p < .01), older

participants tend to reject that technology is allowed

to prolong life stronger than younger participants. In

line with this, older participants also denied more

strongly than younger participants that technology is

allowed to delay death (study 2: r = -.222; p < .01 ;

study 4: r = -.219; p < .01). Consequently, younger

people have less concerns about technology influenc-

ing the end of life than older people.

Figure 7: Evaluation of life-end-decisions and technology

usage (n = 195).

3.7

4.0

4.1

4.3

4.4

4.6

4.8

4.9

5.0

1 2 3 4 5 6

Audio and video recordings

Surveillance

To be complex

Taking over too many tasks

Substitute social contacts

Restricting freedom of choice

Technical failure

Making decisions

independently

Making dependent on

technology

evaluation (min=1; max=6)

rejection agreement

What is lifelogging technology NOT allowed to?

1.8

3.0

4.1

1 2 3 4 5 6

... decide between life and

death."

... delay death."

... prolong life."

evaluation (min = 1; max = 6)

rejection affirmation

"Technology is allowed to...

Guidelines for Integrating Social and Ethical User Requirements in Lifelogging Technology Development

75

5 DISCUSSION & GUIDELINES

This article provides empirical insights into socially

and ethically relevant user requirements for develop-

ment and usage of lifelogging technologies. In addi-

tion to conventional, normative (technical, legal, and

ethical) considerations for lifelogging technology de-

velopment, distinct agreements and rejections of eth-

ically relevant user requirements within our study

confirm the importance of empirical ethical and social

considerations. Otherwise, technically, legally, and

normatively harmonized lifelogging solutions will

lack social acceptance and will not have viable socie-

tal impact. In the following, the research results are

first discussed within the research field of lifelogging

technology perception. Afterwards, guidelines are de-

rived from the research findings (Table 1) and gaps

for future research are highlighted.

5.1 Socio-ethical Insights

In particular, the results referring to socially relevant

aspects revealed insights comparable to previous re-

search in the field. In line with the results of the cur-

rent study, perceived benefits and barriers have al-

ready been proven as relevant factors for lifelogging

technology acceptance (Jaschinski and Allouch,

2015; Peek et al., 2014). In more detail, the current

study confirmed that acceptance depends on the ap-

plication contexts (van Heek et al., 2016) and also on

the respective target group (van Heek et al., 2017a).

In line with previous research (Himmel and Ziefle,

2016), the study also showed that acceptance depends

on the type of technology: e.g., video cameras are not

desired to be used compared to other technologies.

Here, it has to be investigated if this pattern changes

for different privacy-aware camera systems.

Compared to the socially gained insights, the stud-

ies revealed new and specific results referring to eth-

ically relevant requirements. As an example, Wolf et

al. (2014) have emphasized data security and privacy

as most relevant ethical issues. However, specific in-

sights in users’ perception of ethically relevant data

security and privacy parameters as well as concrete

knowledge about ethically accepted or rejected tech-

nologies, functions, and recorded information have

not yet appeared. The current study showed which in-

formation have been seen critically by participants,

how processing of data should be handled, and who

is allowed to have access to data. Existing ethical

frameworks (e.g., Kelly et al., 2013) are mainly based

on normative investigations for a single technology –

here wearable cameras – and include politically and

legally relevant aspects, e.g., data storage should be

“according to national data protection regulations” (p.

318). In contrast, our findings give detailed insights

into future users’ wishes, needs, and requirements re-

garding lifelogging technology use in different situa-

tions. These insights are used to derive guidelines to

integrate socially and ethically relevant user require-

ments into the development of a broad spectrum of

lifelogging technology and for diverse stakeholders.

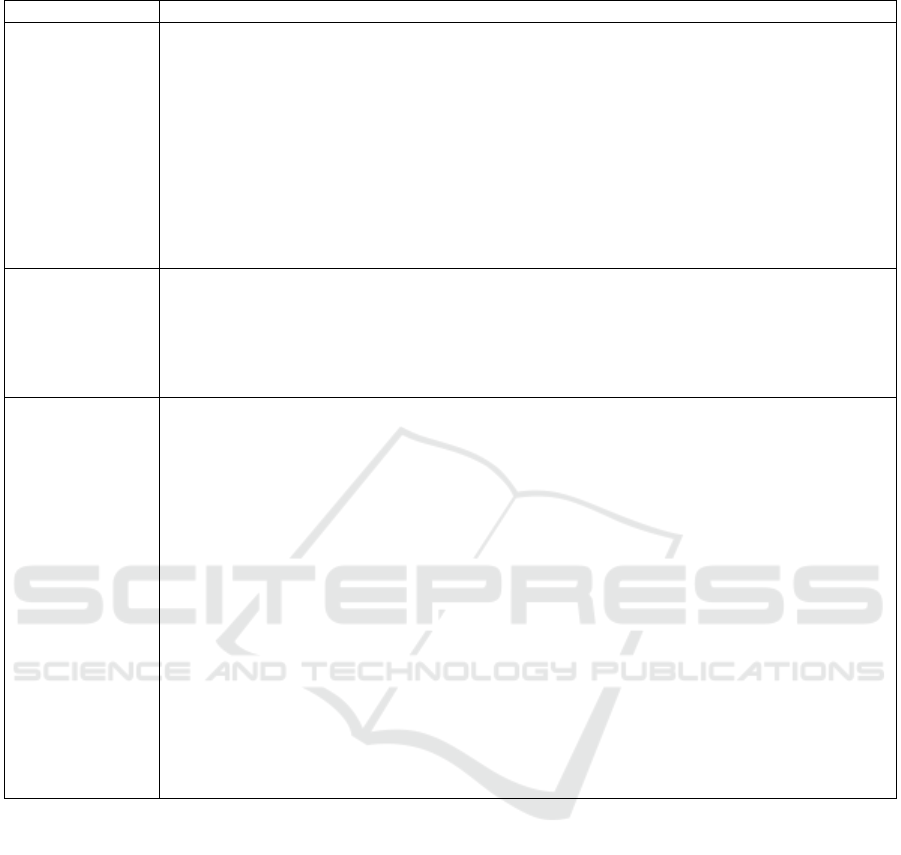

5.2 Lifelogging Technology Guidelines

Guidelines were derived from the studies’ findings

and are detailed in Table 1. Overall, guidelines were

developed for three areas: design of lifelogging tech-

nology, data requirements, and information and com-

munication of lifelogging technology.

A participatory technology “design” is required,

integrating users from initial development phases in-

stead of users’ evaluations of final products. Thereby,

it should focus on decision-making power, specific

technology characteristics, interaction with the tech-

nology, and transparency of the design.

As data security and privacy represent the most

crucial barriers of technology adoption, in the area of

“data requirements” well-defined and transparent

regulations of data handling are essential. In particu-

lar, accepted and rejected data types as well as ways

of data processing should be considered.

Finally, it is of utmost importance to provide users

with open, transparent, and comprehensible “infor-

mation and communication”. Thereby, technology

development should consider which information fu-

ture users need, how accessible information can be

provided, and how technology should be communi-

cated to respective stakeholders.

5.3 Gaps for Future Research

Research on lifelogging perception has mainly fo-

cused on isolated evaluations of benefits and barriers

of using specific technologies. Hence, there is cur-

rently hardly any knowledge about relationships and

trade-offs between beneficial and impeding factors

answering which aspect is more important in deci-

sions on using lifelogging technologies.

A further aspect refers to the majority of existing

studies focusing on country-specific evaluations of

lifelogging technologies. As previous research did

hardly investigate lifelogging perception internation-

ally and cross-culturally, future studies should focus

on direct comparisons of lifelogging perceptions and

relevant ethical issues depending on different coun-

tries, their cultures, and backgrounds.

In addition, future investigations should focus on

ICT4AWE 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

76

Table 1: Guidelines for lifelogging technology development.

further user diversity factors impacting lifelogging

perception and ethically relevant parameters (e.g., at-

titudes towards aging and care, privacy needs). As

there is also hardly any cross-cultural knowledge

about attitudinal characteristics (e.g., attitudes to-

wards aging) and their relationships with (ethical)

lifelogging perceptions, future studies should also

aim for cross-national comparisons in this regard.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank all participants for their openness

to share opinions on lifelogging technologies. Further

thanks go to Simon Himmel and Sean Lidynia for

support, ideas, and encouragement in the collabora-

tion. This work has been funded by the German Fed-

eral Ministry of Education and Research project

PAAL (6SV7955).

REFERENCES

Beringer, R., Sixsmith, A., Campo, M., Brown, J., McClos-

key, R.: The “acceptance” of ambient assisted living:

Developing an alternate methodology to this limited re-

search lens. Proceedings of the International Confer-

ence on Smart Homes and Health Telematics, Springer,

pp. 161–167 (2011)

Biermann, H.; Himmel, S.; Offermann-van Heek, J., Ziefle,

M.: User-specific Concepts of Aging – A Qualitative

Approach on AAL-Acceptance Regarding Ultrasonic

Whistles. In: Zhou J., Salvendy G. (eds). 4th Interna-

tional Conference on Human Aspects of IT for the Aged

Guidelines:

Design

participatory design integrating users iteratively from initial phases

Decision

making power

users want to decide themselves: keep the user in control

technology should not patronize and decide for users

self-determined data sharing policy: sharing of data should be under control of users

optimum: technology profiles with different integrated levels of privacy preservation: should be predefined

but individually adaptable (ideal for diverse applications contexts and stakeholders)

possibility of system deactivation: users should be in control of system’s operation (e.g., emergency switch)

Technology

characteristics

Interaction

keep technologies easy to handle, as easy to learn as possible, as complex as necessary

prevent feelings of heteronomy by well-defined and transparent data handling regulations

design technologies that can be integrated in or combined with (well-known) existing systems (e.g., in care

institutions, smart home systems)

Transparency

enable a transparent overview of functions and performable actions

ask beforehand if a specific action should be performed (depending on context, if possible)

give feedback when a specific action is performed (e.g., transfer of data, activation of alarms or cameras)

Data Requirements

well-defined and transparent regulations of data handling are needed

Type of data

first, focus on safety-relevant functions: emergency detection and calls, monitoring of health parameters

use highly aggregated data (e.g., binary room presence data instead of full sensor data)

prevent a permanent recording of video- or audio-based data; if necessary, enable situational, authorized, and

temporally limited recordings

Data processing

prevent permanent storage, only temporally limited use (as shortly as useful possible; as long as necessary)

enabling authorized and authenticated access to data which can be managed by the user

Information &

Communication

providing open, transparent, and comprehensible information

What?

users have to be informed about: which data are logged? where are data logged? who has access to data?

how long is data stored? why is data stored?

How?

providing accessible information (not too much, essential information first; detailed information on request;

“speak the user’s language”)

give the possibility to "turn off" the personal information gathering at any time

Communication

Strategies

promote benefits of technologies and explain handling of potential barriers (e.g., data security)

short and comprehensible explanation of technology usage and system functioning

promote self-determined decisions of technology handling (e.g., data access)

clearly explain relationships between perceived barriers and benefits (e.g., longer data storage enables

deeper analyses of health development, changes in movements or behaviors)

context- and stakeholder-tailored communication as technologies and their benefits and barriers are per-

ceived differently depending on diverse contexts and user groups:

sports: communicate data handling policy to prevent feeling of being controlled

medical home: consultation and recommendations by doctors can facilitate technology adoption (as doctors

are perceived as accepted and trustworthy)

medical home and professional care: promote that technology usage aims for relief, support in everyday

life, and autonomy enhancement; make clear that technology is no substitute for human attention and care

personnel

age of users: for younger users explaining handling of data- and privacy-related issues should be focused;

for older users potential benefits should be focused in communication

health status: potential benefits of increased safety should be focused for people with chronic illnesses;

clarifying the benefits of the technology for non-affected people by enabling them to empathize with living

with chronic illnesses

Guidelines for Integrating Social and Ethical User Requirements in Lifelogging Technology Development

77

Population, ITAP 2018, pp 231-249, Springer. Cham

(2018)

Bloom, D.E., Canning, D., 2004. Global Demographic

Change: Dimensions and Economic Significance. Na-

tional Bureau of Economic Research. Working Paper

No. 10817.

Bouma, H., Fozard, J.L., Bouwhuis, D.G., Taipale, V.T.:

Gerontechnology in Perspective. Gerontechnology. 6,

190–216 (2007)

Caprani, N., O'Connor, N. E., Gurrin, C.: Investigating

older and younger peoples' motivations for lifelogging

with wearable cameras. In 2013 IEEE International

Symposium on Technology and Society (ISTAS), (pp.

32-41). IEEE (2013)

Caprani, N., Piasek, P., Gurrin, C., O'Connor, N. E., Irving,

K., Smeaton, A. F.: Life-long collections: motivations

and the implications for lifelogging with mobile de-

vices. International Journal of Mobile Human Com-

puter Interaction (IJMHCI), 6(1), 15-36 (2014)

Gall, D., Lugrin, J. L., Wiebusch, D., Latoschik, M. E.: Re-

mind Me: An Adaptive Recommendation-Based Simu-

lation of Biographic Associations. In Proceedings of

the 21st International Conference on Intelligent User

Interfaces (pp. 191-195). ACM (2016)

Gurrin, C., Albatal, R., Joho, H., Ishii, K., 2014a. A privacy

by design approach to lifelogging. In: O'Hara, K., Ngu-

yen, C. and Haynes, P., (eds.) Digital Enlightenment

Yearbook 2014. IOS Press, The Netherlands, pp. 49-73.

Gurrin, C., Smeaton, A. F., Doherty, A. R., 2014b. Lifelog-

ging: Personal big data. Foundations and Trends® in

Information Retrieval, 8(1), 1-125.

Gvercin, M., Meyer, S., Schellenbach, M., Steinhagen-

Thiessen, E., Weiss, B., Haesner, M.: SmartSen-

ior@home: Acceptance of an integrated am- bient as-

sisted living system. Results of a clinical field trial in

35 households. Inform Health Soc Care, 1–18 (2016)

Haustein, T., Mischke, J., Schnfeld, F., Willand, I., Theis,

K., 2016. Older People in Germany and the EU. Detsta-

tis Report. https://www.destatis.de/EN/Publications/Sp

ecialized/Population/BrochureOlderPeopleEU0010021

169 004.pdf?blob=publicationFile.

Hayes, T. L., Abendroth, F., Adami, A., Pavel, M.,

Zitzelberger, T. A., Kaye, J. A.: Unobtrusive assess-

ment of activity patterns associated with mild cognitive

impairment. Alzheimer's & Dementia, 4(6), 395-405

(2008)

Himmel, S., Ziefle, M.: Smart Home Medical Technolo-

gies: Users’ Requirements for Conditional Acceptance.

I-Com, 15(1) (2016)

Jacquemard, T., Novitzky, P., O’Brolcháin, F., Smeaton, A.

F., Gordijn, B. (2014). Challenges and opportunities of

lifelog technologies: A literature review and critical

analysis. Science and engineering ethics, 20(2), 379-

409.

Jalal, A., Kamal, S., Kim, D.: A depth video sensor-based

lifelogging human activity recognition system for el-

derly care in smart indoor environments. Sensors 14(7),

11735-11759 (2014)

Jaschinski, C., Allouch, S.B.: An extended view on benefits

and barriers of ambient assisted living solutions. Int. J.

Adv. Life Sci. 7, 40–53 (2015)

Kelly, P., Marshall, S. J., Badland, H., Kerr, J., Oliver, M.,

Doherty, A. R., Foster, C.: An ethical framework for

automated, wearable cameras in health behavior re-

search. American Journal of Preventive Medicine,

44(3), 314-319 (2013)

Klack, L., Schmitz-Rode, T., Wilkowska, W., Kasugai, K.,

Heidrich, F., Ziefle, M. (2011). Integrated home moni-

toring and compliance optimization for patients with

mechanical circulatory support devices. Annals of bio-

medical engineering, 39(12), 2911-2921(2011)

Lidynia, C., Schomakers, E. M., Ziefle, M.: What Are You

Waiting for? – Perceived Barriers to the Adoption of

Fitness-Applications and Wearables. International

Conference on Applied Human Factors and Ergonom-

ics (pp. 41-52). Springer, Cham. (2018)

Morganti, L., Riva, G., Bonfiglio, S., Gaggioli, A.: Building

collective memories on the web: the Nostalgia Bits pro-

ject. International Journal of Web Based Communities,

9(1), 83-104 (2013)

Nambu, M., Nakajima, K., Noshiro, M., Tamura, T.: An al-

gorithm for the automatic detection of health condi-

tions. IEEE engineering in medicine and biology mag-

azine, 24(4), 38-42 (2005)

Peek, S.T.M., Wouters, E.J.M., van Hoof, J., Luijkx, K.G.,

Boeije, H.R., Vrijhoef, H.J.M.: Factors influencing ac-

ceptance of technology for aging in place: a systematic

review. Int. J. Med. Inform., 83(4), 235-248 (2014)

Pickard, L: A growing care gap? The supply of unpaid care

for older people by their adult children in England to

2032. Ageing & Society, 35(1), 96-123 (2015)

Rashidi, P., Mihailidis, A.: A survey on ambient-assisted

living tools for older adults. IEEE journal of biomedical

and health informatics, 17(3), 579-590 (2013)

Schoeppe, S., Alley, S., Van Lippevelde, W., Bray, N. A.,

Williams, S. L., Duncan, M. J., Vandelanotte, C.: Effi-

cacy of interventions that use apps to improve diet,

physical activity and sedentary behaviour: a systematic

review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition

and Physical Activity, 13(1), 127 (2016)

Schomakers, E.-M., Offermann-van Heek, J., Ziefle, M.:

Attitudes towards Aging and the Acceptance of ICT for

Aging in Place. In: Zhou J., Salvendy G. (eds). 4th In-

ternational Conference on Human Aspects of IT for the

Aged Population. Applications, Services and Contexts.

ITAP 2018, pp 149-169, (LNCS, volume 10926).

Springer: Cham. (2018)

Selke, S: Lifelogging: Digital self-tracking and Lifelog-

ging-between disruptive technology and cultural trans-

formation. Springer (2016)

Shi, G., Chan, C. S., Li, W. J., Leung, K. S., Zou, Y., Jin,

Y.: Mobile human airbag system for fall protection us-

ing MEMS sensors and embedded SVM classifier.

IEEE Sensors Journal, 9(5), 495-503 (2009)

Sun, H., De Florio, V., Gui, N., Blondia, C.: The missing

ones: Key ingredients towards effective ambient as-

sisted living systems. J Ambient Intell Smart Environ,

2(2), 109–120 (2010)

ICT4AWE 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

78

van Heek, J., Arning, K., Ziefle, M.: The Surveillance So-

ciety: Which Factors Form Public Acceptance of Sur-

veillance Technologies? In: Smart Cities, Green Tech-

nologies, and Intelligent Transport Systems (pp. 170-

191). Springer, Cham. (2016)

van Heek, J., Himmel, S., Ziefle, M.: Helpful but spooky ?

Acceptance of AAL-systems contrasting user groups

with focus on disabilities and care needs. In: Proceed-

ings of the 3rd International Conference on Information

and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and

e-Health (ICT4AWE 2017), pp. 78–90 (2017a)

van Heek, J., Himmel, S. Ziefle, M.: Privacy, Data Security,

and the Acceptance of AAL-Systems – a User-Specific

Perspective. In: Zhou J., Salvendy G. (eds) Human As-

pects of IT for the Aged Population. Aging, Design and

User Experience. ITAP 2017. Lecture Notes in Com-

puter Science, vol. 10297. Springer, Cham, pp 38-56

(2017b)

van Heek, J., Himmel, S., Ziefle, M.: Caregivers’ perspec-

tives on ambient assisted living technologies in profes-

sional care contexts. In: 4th International Conference

on Information and Communication Technologies for

Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2018). SCITE-

PRESS (2018)

Walker, A., Maltby, T., 2012. Active ageing: a strategic

policy solution to demographic ageing in the European

Union. Int. J. Soc. Welf., 21, 117–130.

Wang, L., Gu, T., Tao, X., Lu, J.: Sensor-based human ac-

tivity recognition in a multi-user scenario. In European

Conference on Ambient Intelligence, pp. 78-87,

Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg (2009)

Wilkowska, W., Ziefle, M., 2011. User diversity as a chal-

lenge for the integration of medical technology into fu-

ture smart home environments. In: Ziefle, M., Rcker,

C. (eds.) Human-Centered Design of E-Health Tech-

nologies: Concepts, Methods and Applications, pp. 95–

126. Medical Information Science Reference, New

York.

Wilkowska, W., Ziefle, M., Himmel, S.: Perceptions of Per-

sonal Privacy in Smart Home Technologies: Do User

Assessments Vary Depending on the Research

Method? In Int Conference on Human Aspects of Infor-

mation Security, Privacy, Trust. Springer, pp. 592–603

(2015)

Wolf, K., Schmidt, A., Bexheti, A., Langheinrich, M.: Life-

logging: You're wearing a camera? IEEE Pervasive

Computing, 13(3), 8-12 (2014)

Guidelines for Integrating Social and Ethical User Requirements in Lifelogging Technology Development

79