Practising Public Speaking: User Responses to using a Mirror versus a

Multimodal Positive Computing System

Fiona Dermody and Alistair Sutherland

School of Computing, Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland

Keywords:

Real-time feedback, Multimodal Interfaces, Positive Computing, HCI, Public Speaking.

Abstract:

A multimodal Positive Computing system with real-time feedback for public speaking has been developed.

The system uses the Microsoft Kinect to detect voice, body pose, facial expressions and gestures. The system

is a real-time system, which gives users feedback on their performance while they are rehearsing a speech. In

this study, we wished to compare this system with a traditional method for practising speaking, namely using

a mirror. Ten participants practised a speech for sixty seconds using the system and using the mirror. They

completed surveys on their experience after each practice session. Data about their performance was recorded

while they were speaking. We found that participants found the system less stressful to use than using the

mirror. Participants also reported that they were more motivated to use the system in future. We also found

that the system made speakers more aware of their body pose, gaze direction and voice.

1 INTRODUCTION

As the saying goes ’practice makes perfect’. This is

particularly true for Public Speaking. In this paper

we are focusing on two different approaches to prac-

tising public speaking. The first approach is the tra-

ditional way of practising speaking, which is to speak

in front of a mirror. This has been recommended by

Toastmasters International, an international organisa-

tion that helps people develop their communication

skills (Toastmasters International, 2018). An addi-

tional reason for choosing this approach is that most

people would have access to a mirror. While a mir-

ror may be accessible, there are a number of issues

with it. It is dependent on the speaker’s own subjec-

tive assessment of their speaking performance. Peo-

ple do not always like seeing themselves speak in

a mirror. A similar finding was found in our pre-

vious study (Dermody and Sutherland, 2018a). We

noted that the majority of speakers did not like seeing

themselves represented in live video stream as they

found it distracting. We also reported that speakers

when seeing themselves on video tended to focus less

on their speaking and more on their physical appear-

ance. Finally, a mirror cannot give any feedback on

the speaker’s voice.

The second approach is to practise using a multi-

modal Positive Computing System, which will be de-

scribed in this paper.

In our previous study we compared user responses

to seeing themselves on screen represented as an

avatar and video stream. In both instances, visual

feedback was displayed by the system to the users. In

this study we are comparing the avatar version of the

system with a mirror. When using the system users

receive visual feedback on their speaking behaviour.

No feedback was provided by the mirror. Users just

saw their own reflection.

2 POSITIVE COMPUTING

Positive Computing is a paradigm for human-

computer interaction (Calvo and Peters, 2015),

(Calvo and Peters, 2014), (Calvo and Peters, 2016). It

has been put forward as an appropriate paradigm for

multimodal public speaking systems (Dermody and

Sutherland, 2018b). This can be illustrated by look-

ing at the spheres of Positive Computing, see Fig-

ure 1. In relation to multimodal systems for pub-

lic speaking, the external activity is the user’s speak-

ing ability, the technology environment is the multi-

modal system and the personal development is a re-

duction in stress while speaking in public. As noted

by (Dermody and Sutherland, 2018b), using the sys-

tem should be an enjoyable experience and should

not add to any anxiety already experienced by a user.

Dermody and Sutherland made the following rec-

Dermody, F. and Sutherland, A.

Practising Public Speaking: User Responses to using a Mirror versus a Multimodal Positive Computing System.

DOI: 10.5220/0007694101950201

In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications (VISIGRAPP 2019), pages 195-201

ISBN: 978-989-758-354-4

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reser ved

195

ommendations: Users should not feel stressed or dic-

tated to when interacting with the system. While

visual feedback is displayed by the system, users

have the choice or autonomy over what feedback they

choose to react to. The other point in relation to feed-

back is that the feedback is non-directive. The pur-

pose of the feedback is to make the user aware of

their speaking behaviour, not to tell them what to do.

During a review of the multimodal system for pub-

lic speaking, Presentation Trainer, experts found that

the system should ’shift focus and become a tool to

develop awareness of nonverbal communication, in-

stead of correcting it’ (Schneider et al., 2017). Users

should see themselves represented on screen as a full

3D avatar because this allows them to assess their full

3D body pose but does not distract them with details

of their personal appearance. The research question

posed in this paper is, how do users respond to these

two approaches?

Figure 1: The Spheres of Positive Computing (Calvo and

Peters, 2014).

3 SYSTEM DESCRIPTION

We will present a brief description of our multi-

modal Positive Computing system for public speak-

ing. It has been described in greater depth in our

previous work (Dermody and Sutherland, 2016),(Der-

mody and Sutherland, 2018a),(Dermody and Suther-

land, 2018b).The term ‘multimodal’ refers to the fact

that the system detects multiple speaking modes in

the speaker such as their gestures, voice and eye con-

tact. Gestures, body posture, gestures and gaze di-

rection are all important aspects of public speaking

(Toastmasters International, 2011), (Toastmasters In-

ternational, 2008). The user can select if they want

to receive feedback on all speaking modes or a subset

of them. The system consists of a Microsoft Kinect 1

connected to a laptop. The system uses the Microsoft

Kinect to sense the user’s body movements, facial ex-

pressions and voice. The user stands in front of the

system and speaks. The speaker can see themselves

represented on screen as an avatar. Visual feedback is

given on a laptop screen in front of the user. The feed-

back is displayed in proximity to the area it relates to.

The objective of the system is to enable the user to

speak freely without being interrupted, distracted or

confused by the visual feedback on screen.

3.1 System Feedback

Feedback on the speaker’s voice is given by a track,

which consists of a moving line where the horizontal

axis represents time and the vertical axis represents

pitch. The width of the line represents volume i.e. the

loudness with which the user speaks. Syllables are

represented by different colours. The density of the

syllables represents the speed with which the user is

speaking.

The system also displays a visual feedback icon

near the avatar’s hands to indicate that the user is

touching their hands. Feedback is also given on gaze

direction using arrows near the avatar’s head. The

aforementioned feedback can be seen in Figure 2. For

the purposes of this study, we chose to only look at

these feedback items. However, the system can pro-

vide feedback on other speaking behaviours as de-

tailed in our previous work. These particular speaking

behaviours were chosen because they have been rated

as important by experts in public speaking (Toastmas-

ters International, 2011), (Toastmasters International,

2008). A speaker’s open gestures and varying eye

contact have been found to impact on audience en-

gagement.

4 STUDY DESIGN

The study had 10 participants (4F, 6M). Participants

were selected from the staff and student body at our

university. The study was designed to be a one-

time recruitment with a duration of 25 minutes per

participant. The participants completed a prelimi-

nary questionnaire on demographic information and a

post-questionnaire. 9 of the participants were novice

speakers who had done some public speaking but

wished to improve their skills in this area. One partic-

ipant described himself as an accomplished speaker

who was keen to participate in the study. None of the

participants had used a multimodal system for public

speaking previously.

The post-questionnaire consisted of eleven items.

User experience was evaluated using three questions

on naturalness, motivation to use the application again

HUCAPP 2019 - 3rd International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

196

Figure 2: System Display with the user represented as the

avatar. The feedback is displayed on gaze direction, hands-

touching and voice graph. The voice graph represents the

pitch of the user’s voice. The colours represent different

syllables and the width of the line represents the volume

(loudness) of the voice.

and stress experienced using the application. Aware-

ness was evaluated using four questions on awareness

of feedback and speaking behaviour, anything learned

during the test session. Participants were also asked

a question on whether they had used a digital system

or mirror to practise their public speaking in the past.

An open question was added asking what the partici-

pant liked about using the mirror/system. A final open

question was added for additional comments.

4.1 Pretest

A pretest, consisting of one participant, was con-

ducted to test the experimental setup and the study

surveys.

An interesting point was noted during the pretest.

The pretest participant remarked that she always

speaks with her hands held together. While she was

aware of the feedback being displayed by the system

highlighting that her hands were together, she chose

to keep them together because ’that is the way I speak.

I feel comfortable speaking like this’. It raised an in-

teresting issue in relation to evaluating a system like

this because it shows that users may be aware of feed-

back but may not react to it. In other words, the feed-

back may not result in an observable change in user

Figure 3: Study Setup using full-length Mirror.

Figure 4: Study setup using system.

speaking behaviour. This can make evaluating a sys-

tem like this challenging because different users may

react differently to feedback. Some users may re-

spond to it but some users may choose not to but in

both cases users are aware of the feedback.

4.2 Experimental Setup

The experiment was setup as per Figures 3, 4 for the

two separate test conditions. For the system setup,

participants stood in front of a table supporting a lap-

top and a Microsoft Kinect. For the mirror setup, par-

ticipants stood in front of the table supporting the Mi-

crosoft Kinect and a full length mirror. The partici-

pant was not able to see any feedback displayed by

the system in this setup.

4.3 Study Format

Each session opened with an introduction consisting

of an overview of the study format. In accordance

with GDPR requirements a plain language statement

outlining the format of the study was read to each

participants. Participants were then invited to ask

Practising Public Speaking: User Responses to using a Mirror versus a Multimodal Positive Computing System

197

any questions. Following the signing of the Informed

Consent form, each participant was given a short in-

troduction to effective public speaking. This intro-

duction described how beneficial it was to use ges-

tures, vocal variety, facial expressions and eye contact

while speaking. The benefits of using open gestures

and varying gaze direction were mentioned with ref-

erence to audience engagement.

The researcher then presented each participant

with a demonstration of how the multimodal system

for public speaking worked with particular emphasis

on the different types of visual feedback displayed.

Participants were then invited to familiarise them-

selves with the system so they gained familiarity with

the feedback displayed. Participants were then invited

to familiarise themselves with the mirror. Mirror po-

sition and angle was calibrated for each participant to

ensure they could see themselves clearly while speak-

ing. The experimental setup was then adjusted to al-

low for whichever test condition was first. Partici-

pants were asked to speak for one minute on a subject

of their choice using the system or the mirror. Five of

the participants used the system first followed by the

mirror. The other five participants used the mirror first

followed by the system. Speakers completed the post-

questionnaire twice, immediately after using the sys-

tem and immediately after using the mirror. The post-

questionnaires contained the same items each time.

At the end of the study, there was a short closing in-

terview.

The questionnaire asked them to rate different as-

pects of the version, which they had just used, on a

scale of 1 to 10. Users could also add optional written

comments after each question.

5 RESULTS

The order in which the participants used the versions

(system first or mirror first) could potentially be a con-

founding variable. Therefore, the users were divided

into two equal-sized groups (system first and mirror

first), in order to measure any effect that this variable

might have. Six participants reported that they had

used a mirror before to practise public speaking in the

past. None of the participants had used a multimodal

system for public speaking before.

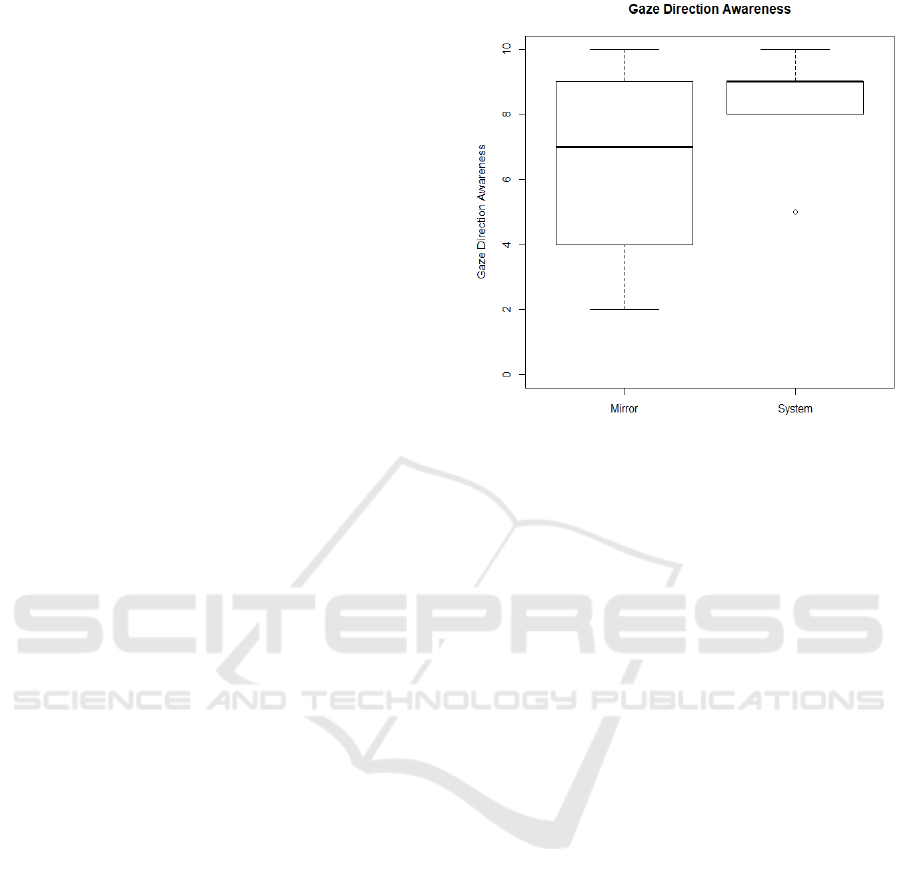

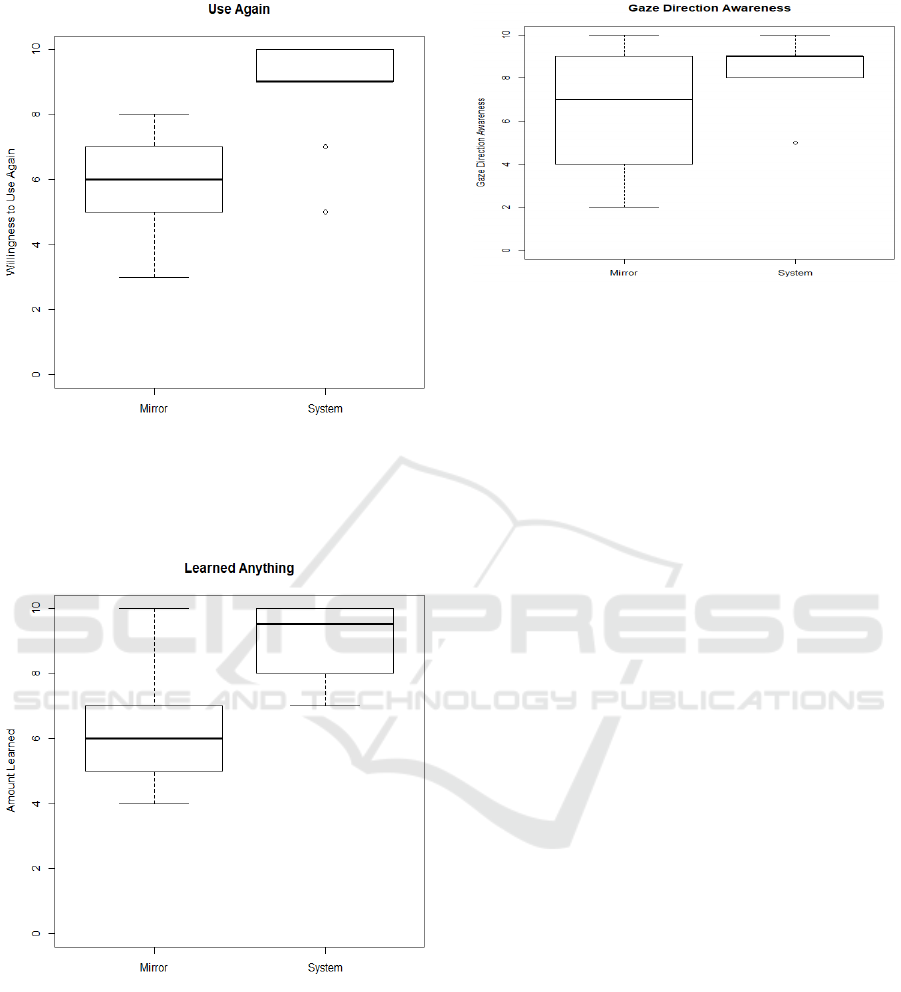

In all the questions on the questionnaire, the users

expressed a preference for the system over the mir-

ror. But they expressed particularly strong prefer-

ences on the following three questions – “whether

they would use the system again”, “voice awareness”

and “whether they had learned anything”. The box-

plots of the responses are shown in Figures 5,6,7,8.

Figure 5: Boxplots of the responses for system and mirror

in answer to the question of voice awareness. The higher the

score, the higher was the voice awareness. As can be seen,

participants reported that they were more aware of voice

when using the system.

T-tests showed a p-value of less than .01 in all three

cases, suggesting that the differences were highly sig-

nificant. The t-test for gaze direction awareness was

approaching significance with a value of 0.09 as seen

in Figure 8.

In the case of “voice awareness” it is understand-

able that the users would prefer the system over the

mirror. Users mentioned the voice track on the system

made them aware of “characteristics of their voice” or

“changes in their voice”. In the case of “whether they

had learned anything”, users mentioned their body

pose, their gestures, their gaze direction and their

voice characteristics. They all mentioned that it was

easier to learn these things from the system rather than

the mirror. In the case of “whether they would use the

system again”, users said that the system was enjoy-

able to use and that it was less stressful than the mirror

and that it was less distracting. These are results simi-

lar to those, which we found in our previous paper, in

which users preferred the avatar to live video. As in

that case, users did not like looking at themselves.

6 DISCUSSION OF DATA

RECORDED DURING SPEECH

Whilst each participant was speaking, the system

recorded data about their voice, hands and gaze direc-

tion. At each second, the system recorded the number

HUCAPP 2019 - 3rd International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

198

Figure 6: Boxplots of the responses for system and mirror

in answer to the question of using again. The higher the

score, the more participants wanted to use again. As can

be seen, participants reported that they wanted to use the

system again more than the mirror.

Figure 7: Boxplots of the responses for system and mirror

in answer to the question of what users learned. The higher

the score, the more participants reported they had learned.

As can be seen, participants reported that they had learned

more when using the system.

of syllables spoken in the previous second. At each

frame (at a frame rate of 30fps), it recorded whether

the participant’s hands were touching and whether the

gaze direction icon was activated. This icon is acti-

vated, if the user has not varied their gaze direction

for more than 15 seconds. Fig 9 and 10 shows a sam-

Figure 8: Boxplots of the responses for system and mirror

in answer to the question of gaze direction awareness. The

higher the score, the more aware was the version. As can

be seen, participants reported that they were more aware of

gaze direction when using the system.

ple pair of recordings.

In this case, it shows whether the hands were

touching. Figure 9 was recorded while the partici-

pant was using the mirror and Figure 10 was recorded

while the same participant was using the system. In

this case, it can be seen that the participant’s hands

were touching continuously over long periods while

the participant was using the mirror, whereas the

hands touched only briefly while the participant was

using the system. Out of the 10 participants, 3 showed

no hand or gaze events, when using either the mirror

or the system. In other words, they never touched

their hands and never activated the gaze direction

icon. During the post-test interview, it turned out

that one of these participants had previous training

as an actor and another had a lot of previous expe-

rience of making presentations in his role as a science

communicator. Of the remaining 7, 4 showed a pat-

tern similar to that shown in Figures 9 and 10, i.e.

they showed significant hand or gaze events, when

using the mirror, and significantly less, when using

the system. Of the remaining 3, one showed no dif-

ference between the mirror and the system. And the

other two showed more events when using the sys-

tem. We would need a much larger group of partici-

pants to decide whether the system is actually affect-

ing the speaker’s behaviour. From this small study,

we can suggest that previous experience of speaking

might be a confounding variable. In addition, cultural

factors may play a role. For example, in some cul-

tures, clasping hands may be a sign of respect for the

audience. The speaker’s personality may also be a

factor. One of our participants said that, when they

saw the hands icon, they felt that they “were doing

something wrong” and so they responded quickly. In

contrast, another participant, who frequently touched

Practising Public Speaking: User Responses to using a Mirror versus a Multimodal Positive Computing System

199

Figure 9: Graph displaying whether the speaker’s hands are

touching during a 60 second speech in front of the mirror.

Frame rate is 30fps.

Figure 10: Graph displaying whether the speaker’s hands

are touchin during a 60 second speech in front of the system.

Frame rate is 30fps. The speaker touches their hands less

often than they did when using the mirror.

their hands, said “that is just the way I speak”. One

of the fundamental principles of Positive Computing,

on which our research is based, is that the user should

have the autonomy to make their own decisions. The

icons are to make the user aware of their behaviour.

The icons are not instructions for the user to follow.

7 CONCLUSION

From the results of the questionnaire, we can con-

clude that users find the system less stressful than

using the mirror and are more motivated to use the

system again. We can also conclude that the sys-

tem makes speakers more aware of their body pose,

gaze direction and voice. From the results of the data

recorded during speeches, we can conclude that users

may or may not always respond to that awareness.

They may choose to ignore the information, which the

system is giving them. In future work, we may follow

some of the participants’ suggestions. We could prove

a report or summary of the speaker’s behaviour during

the speech. One user asked for a score to indicate how

well they were doing. Users may also review a record-

ing of their speech with feedback displayed. We may

also include a virtual audience which responds to the

speaker’s behaviour.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This material is based upon works supported by

Dublin City University under the Daniel O’Hare Re-

search Scholarship scheme. System prototypes were

developed in collaboration with interns from École

Polytechnique de l’Université Paris-Sud and l’École

Supérieure d’Informatique, Électronique, Automa-

tique (ESIEA) France.

REFERENCES

Calvo, R. A. and Peters, D. (2014). Positive Computing:

Technology for wellbeing and human potential. MIT

Press.

Calvo, R. A. and Peters, D. (2015). Introduction to Posi-

tive Computing: Technology That Fosters Wellbeing.

In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference

Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing

Systems, CHI EA ’15, pages 2499–2500, New York,

NY, USA. ACM.

Calvo, R. A. and Peters, D. (2016). Designing Technology

to Foster Psychological Wellbeing. In Proceedings

of the 2016 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on

Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI EA ’16,

pages 988–991, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Dermody, F. and Sutherland, A. (2016). Multimodal system

for public speaking with real time feedback: a positive

computing perspective. In Proceedings of the 18th

ACM International Conference on Multimodal Inter-

action, pages 408–409. ACM.

Dermody, F. and Sutherland, A. (2018a). Evaluating User

Responses to Avatar and Video Speaker Representa-

tions A Multimodal Positive Computing System for

Public Speaking. In Proceedings of the 13th Inter-

national Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imag-

ing and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications

(VISIGRAPP 2018), volume HUCAPP, pages 38–43,

Madeira. INSTICC.

Dermody, F. and Sutherland, A. (2018b). Multimodal Sys-

tems for Public Speaking - A case in support of a Pos-

itive Computing Approach. In Proceedings of the 2nd

International Conference on Computer-Human Inter-

action Research and Applications (CHIRA 2018), vol-

ume CHIRA, Seville. INSTICC.

Schneider, J., Börner, D., Rosmalen, P., and Specht, M.

(2017). Presentation Trainer: what experts and com-

puters can tell about your nonverbal communication.

Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 33(2):164–

177.

HUCAPP 2019 - 3rd International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

200

Toastmasters International (2008). Competent Communica-

tion A Practical Guide to Becoming a Better Speaker.

Toastmasters International (2011). Gestures: Your Body

Speaks. Available from: http://www.toastmasters.org.

Toastmasters International (2018). Prepar-

ing A Speech. Available from:

https://www.toastmasters.org/resources/public-

speaking-tips/preparing-a-speech.

Practising Public Speaking: User Responses to using a Mirror versus a Multimodal Positive Computing System

201