SMILE Goes Gaming: Gamification in a Classroom Response System for

Academic Teaching

Leonie Feldbusch, Felix Winterer, Johannes Gramsch, Linus Feiten and Bernd Becker

Chair of Computer Architecture, University of Freiburg, Georges-K

¨

ohler-Allee 51, Freiburg, Germany

Keywords:

Gamification, Game-based Learning, Classroom Response System, Higher Education, Computer Science,

Computer Engineering, SMILE.

Abstract:

The classroom response system SMILE (SMartphones In LEctures) is regularly used in academic lectures.

Among other features, it enables lecturers to start quizzes that can be answered anonymously by students on

their smartphones. This aims at both activating the students and giving them feedback about their understand-

ing of the current content of the lecture. But even though many students use SMILE in the beginning of a

course, the number of active participants tends to decrease as the term progresses. This paper reports the

results of a study looking at incorporating gamification into SMILE to increase the students’ motivation and

involvement. Game elements such as scores, badges and a leaderboard have been integrated paired with a

post-processing feature enabling students to repeat SMILE quizzes outside of the lectures. The evaluations

show that the gamification approach increased the participation in SMILE quizzes significantly.

1 INTRODUCTION

SMILE (SMartphones In LEctures) is a classroom

response system with different functionalities. One

of its most popular features is the quiz functional-

ity that enables lecturers to start multiple-choice or

multiple-response quizzes which the students can an-

swer anonymously using their internet-capable de-

vices like smartphones, tablets or laptops. The lec-

turer sees how well students performed and can there-

upon adapt the course of the lecture accordingly.

SMILE has been used in academic lectures since

2011 (K

¨

andler et al., 2012; Feiten et al., 2012).

Using a classroom response system with adequate

quizzes is not only useful for students (to know if they

properly understood the content of the lecture) but

also for the lecturer (to evaluate if the given expla-

nations were understandable and to activate the stu-

dents to engage more with the lecture content). How-

ever, there has often been a noticeable decrease of par-

ticipation during the term, resulting in only a small

number of students still participating in the lecturer’s

quizzes near the end of term. There can be many rea-

sons for that, such as students generally not attend-

ing the course any more, not understanding why us-

ing SMILE is useful, or simply not having fun using

SMILE. So far we have only been able to verify that

the first of these reasons – students dropping out of the

course – is definitely a major contributor to this de-

crease of SMILE users. However, even among the re-

maining students there is a great potential to increase

the number of SMILE users, which was the initial mo-

tivation for the study presented here.

We therefore extended SMILE by incorporating

concepts of gamification, such as scores, badges,

achievements, levels, pop-ups for feedback, a user-

pseudonym appearing on a leaderboard, and an op-

tion for the students to personalise the colour scheme

of their SMILE client. Additionally, students are now

able to repeatedly answer the live quizzes outside of

the lecture (e.g. at home). Lecturers are provided with

an overview of statistics, such as gained scores and

achieved levels. Furthermore, they are able to set

parameters, such as the number of (correct) quiz an-

swers required for certain achievements, or individual

level names.

In this paper we describe an approach to deter-

mine game elements suitable for academic teaching

purposes, based on concepts and definitions presented

in literature. Furthermore, we report the evaluation

of applying this first prototype in a Computer Engi-

neering course for first semester students in the winter

term 2017/18 at the University of Freiburg, Germany.

The results are compared to the same course held the

year before, where SMILE without gamification had

been used. The evaluation shows:

268

Feldbusch, L., Winterer, F., Gramsch, J., Feiten, L. and Becker, B.

SMILE Goes Gaming: Gamification in a Classroom Response System for Academic Teaching.

DOI: 10.5220/0007695102680277

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2019), pages 268-277

ISBN: 978-989-758-367-4

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

• a significant increase of SMILE usage compared

to the winter term 2016/17.

• many students having fun using the new game el-

ements and thus feeling more motivated to use

SMILE.

• the potential of reaching the students not only dur-

ing class but also outside the lecture via the quiz

repeating system.

The remainder of this paper is structured as fol-

lows: Section 2 presents the definition and previous

use cases of gamification. Section 3 then gives an

introduction to the non-gamified version of SMILE

before presenting the new gamification features and

their relevance in the given context. Section 4

presents the evaluation results of the prototype’s first

use, before the conclusions are drawn in Section 5.

2 RELATED WORK

The word “gamification” was originally defined by

Deterding et al. (2011) as the use of game elements in

a non-gaming context. Their definition distinguishes

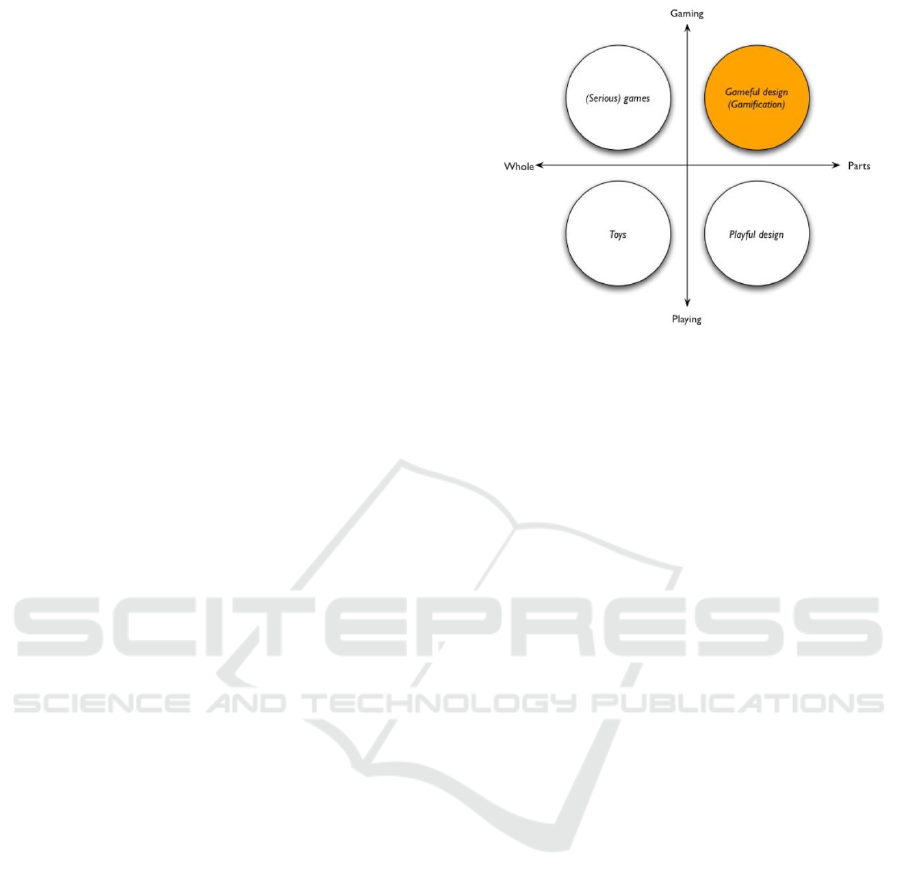

between four different aspects shown in Figure 1:

gameful design (gamification), (serious) games, play-

ful design, and toys. They differentiate the concepts

of game and play, with a play being free and a game

having rules. Whole means that playing or gaming

is in the foreground: for example in learning con-

text where the students use games for learning. How-

ever, it is also possible to partly use game elements

e.g. in non-gaming contexts. Regarding SMILE we

have added game elements to its basic functionality,

so our work falls into the gamification category.

Literature presents gamification as a powerful

possibility to evoke desired behaviour (AlMarshedi

et al., 2017). It has been evaluated concerning the

increase of motivation and learning benefit (Sailer,

2016; Yildirim, 2017). Sailer (2016) discovered that

scores, badges, leaderboards, avatars, etc. fulfil ba-

sic psychological needs. Satisfying these needs can

have a positive impact on motivation and on quanti-

tative and qualitative performance. Yildirim (2017)

published a study that records the positive impact of

gamification in a university lecture. Wang (2015) con-

ducted a survey about whether game elements have a

positive long-term effect, or whether there are “wear-

out effects” when students get used to gamification.

It was shown that gamification does in fact retain

its positive impact on students regarding engagement,

motivation, concentration and learning.

Glover (2013) gives an overview of when and how

gamification can be used in learning contexts. He

Figure 1: The difference between play and game, with play

being free and game having rules, and between wholly and

partly, with wholly meaning that the game or play is in the

foreground and partly meaning that only some elements of

gaming/playing are used. (Deterding et al., 2011).

proposed a set of questions to determine the use of

gamification. In the following we answer these ques-

tions regarding SMILE, showing that the endeavour

of gamification is recommendable:

• Q: “Is motivation actually a problem?”

A: Yes, because the use of SMILE is decreasing

during the term.

• Q: “Are there behaviours to encourage/dis-

courage?”

A: Yes, we want to encourage the use of SMILE.

• Q: “Can a specific activity be gamified?”

A: Yes, the activity of answering quizzes can be

gamified.

• Q: “Am I creating a parallel assessment route?”

A: No, because as SMILE is anonymous, scores

and leaderboards are disconnected from the for-

mal assessment of learning.

• Q: “Would it favour some learners over others?”

A: No, because the usage of SMILE is rec-

ommended but not required. Thus there is no

favouritism at all.

• Q: “What rewards would provide the most moti-

vation for learners?”

A: We see scores, badges, achievements, levels,

feedback pop-ups, a leaderboard and personalisa-

tion as promising (cf. Section 3.2).

• Q: “Will it encourage learners to spend dispro-

portionate time on some activities?” and “Are re-

wards too easy to obtain?”

A: No, because it is neither possible to obtain the

rewards by spending disproportionate time nor are

they too easy to obtain (also cf. Section 3.2).

SMILE Goes Gaming: Gamification in a Classroom Response System for Academic Teaching

269

Since 2011 the number of studies concerning gam-

ification has risen significantly (Darejeh and Salim,

2016). In the following we present some of these

studies and show what sets our work apart:

Berkling and Thomas (2013) implemented gami-

fication into a course of Software Engineering at the

Cooperative State University in Karlsruhe. They re-

placed the lecture with independent learning phases,

using given material and a game environment. Stu-

dents, however, were not able to cope with the free

time management but 55% nevertheless liked the idea

of a gamified lecture or at least thought that it would

work with small adjustments. In our work we do not

replace the whole lecture with self-regulated learning

but only gamify SMILE, the classroom response sys-

tem in use.

Denny (2013) published a study of a badge-based

achievement system. In his large-scaled evaluation

he found that a significant positive effect can be ob-

served in the attendance of the online learning tool

“PeerWise” without decreasing the quality of learn-

ing. Students have fun getting badges and seeing them

in their user interface. In SMILE we go even further

by including not only badges and achievements but

also scores and a leaderboard.

The study of Cheong et al. (2013) concerns a gam-

ified multiple-choice quiz tool that is used in several

different Bachelor degree courses at the RMIT Uni-

versity of Melbourne. The authors did a survey with

students assessing their subjective opinion of the tool.

The engagement, fun and learning of the students

were evaluated almost exclusively positively. We also

use a quiz tool for our study but furthermore compare

our observations with a previous year in which gami-

fication had not been used.

Ohno et al. (2013) introduced “half-anonymity”

and gamification into a lecture to increase the moti-

vation and engagement of students to ask questions.

They used the “Classtalk”-Software and developed an

application the students could use to discuss quizzes

online and vote for the answers until the lecturer

closed the question. The 17 surveyed students over-

all evaluated the system positively and would have

liked to use it in further lectures as well. In SMILE

the students can use pseudonyms, which is similar

to the “half-anonymity”, but they can also stay com-

pletely anonymous if they want to. Furthermore, we

also do quizzes during the lecture but the students are

discussing “offline” (face-to-face) instead of online.

Another difference is that our study has more partici-

pants.

The publication of Fotaris et al. (2016) describes

a programming course that used the tools “Kahoot!”,

“Who wants to be a millionaire” and “Codecademy”,

readily providing different game elements. This

course was compared to a control group not using

gamification, regarding a number of key metrics like

course attendance, course material downloads or final

grades, and it was concluded that gamification is en-

riching for both students and instructors. In contrast

to this study, we only use one system and apply all

game elements to it.

Also using a self-developed system, the study of

Barrio et al. (2016) analyses the use of game dynam-

ics and real-time feedback in “IGC”, a classroom re-

sponse system very similar to SMILE. In their system,

however, the students are not completely anonymous

as lecturers are able to see the browser types and IP

addresses. For their study they used IGC in four 90-

minute lectures and did their evaluation in four dif-

ferent categories: motivation, attention, engagement

and learning performance. In contrast, SMILE is used

during the whole term (26 90-minute lectures). We

execute two evaluations in two different lectures using

seven different question categories: attention, self-

efficacy, meta cognition, motivation, understanding,

fun and recommendation.

For our own work we focus on the suggestions

by Follert and Fischer (2015) who already developed

game design elements for the academic learning con-

text. They used an e-learning platform called Opal

where lecturers are able to distribute teaching mate-

rial, while students can find study-related information

and come together in working groups (TU Dresden,

2017). However, they never put forth an evaluation of

their exploration in this field. We emulate their devel-

opment steps for our own work as described in Sec-

tion 3.2 and then also evaluate the resulting prototype

in our whole-term field test.

3 GAMIFICATION IN SMILE

The main intention of adding gamification to SMILE

has been to increase the students’ motivation to per-

sistently participate in the quizzes during the lectures.

For this purpose we implemented several game ele-

ments into the client and the possibility of repeating

quizzes outside of the lecture, for which the students

would also get rewards in the gamification context.

In this chapter, we briefly describe the previous non-

gamified version of SMILE before explaining in de-

tail the added game elements of the new prototype.

3.1 Non-gamified SMILE

The SMILE application consists of three modules:

“Quiz”, “Q&A” and “Feedback”. Each module can

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

270

be accessed by the lecturer and the students in sepa-

rate SMILE clients using a web browser on arbitrary

devices. Furthermore, the lecturer is able to adminis-

ter the modules in their client. As students remain

anonymous, the lecturer cannot extract information

about a specific student.

Via the Quiz module a lecturer has the ability

to conduct multiple-choice or multiple-response live

quizzes during the lecture. Students attending the lec-

ture can answer a quiz in a fixed amount of time via

the SMILE student client. After each quiz the lecturer

is able to see a statistic about the given answers and

can discuss and incorporate the results in the remain-

der of the lecture. It is up to the lecturer to publish the

correct answer of a quiz as well as an explanation text

to the students in the end.

The Q&A module is a forum where students have

the opportunity to ask questions at any time. The

questions can be answered by the lecturer, by teaching

assistants (if available) or by other students. Further-

more, it is possible to up- or down-vote forum entries.

There is no difference between the SMILE student or

lecturer client for this module.

In the Feedback module the students are able to

give live feedback during a lecture. To do so they use

a slider in the student client to show whether they are

keeping up with the content of the lecture. In the lec-

turer client the distribution of all slider positions is

shown in a histogram, that may be interpreted by the

lecturer in real-time to adapt the speed of the lecture

accordingly. Furthermore, the students might be en-

couraged to ask questions if the lecturer chooses to

publish this live histogram, when they see that they

are not the only ones struggling.

Past evaluations of SMILE showed, however, that

the Feedback module does not have the desired effect.

Also the Q&A module has remained unused most of

the times as most lecturers already use another forum

for their lectures. The use of the Quiz module, how-

ever, was very successful in raising the students’ inter-

activity and revealing their misconceptions (K

¨

andler

et al., 2012). For these reasons we only focus on the

Quiz module for further investigation.

We dubbed the new SMILE version including

game elements gamified SMILE. In contrast, the

SMILE version without any new (gamification) fea-

tures shall be called basic SMILE.

3.2 New Game Elements

To realise the gamification of SMILE we used game

elements according to the eight gamification cate-

gories defined by Chou (2015): meaning, accom-

plishment, empowerment, ownership, social influ-

ence, scarcity, unpredictability and avoidance. Based

on these categories, Follert and Fischer (2015) pro-

posed their own game elements for academic teaching

context in the e-learning platform “Opal”.

Using the propositions of Follert and Fischer

(2015) as orientation, we developed the following

game elements in SMILE:

• a score system

• badges

• achievements

• a (named) level system

• a leaderboard

• pop-ups for feedback

• pseudonyms and choice of colour scheme

In addition to our literature research about possi-

ble game elements we did a pre-survey with 40 basic

SMILE users asking for their opinion and wishes on

introducing game elements into SMILE. The results

showed that basic SMILE was considered to be very

useful for understanding the content of the lecture. In

addition to the current functionality a majority of stu-

dents requested an option to answer the quizzes again

at home. Thus, we implemented a facility to repeat

quizzes outside of the lecture (post-processing). In

the following, we explain how our developed game

elements fulfil the eight different gamification cate-

gories of Chou (2015).

Meaning: The game elements of the meaning

category aim to make the users aware of the big-

ger meaning (i.e. the purpose) behind the application

(Chou, 2015). An intuitive welcome page explaining

the benefits and the usage of the application e.g. with a

tutorial could be an example for this category (Follert

and Fischer, 2015). For SMILE there already exists an

intuitive welcome page providing such explanations.

Accomplishment: This category contains ele-

ments to increase the motivation for making progress

or developing skills (Chou, 2015). In this context, re-

ward mechanisms such as badges or scores are very

important (Follert and Fischer, 2015). To apply this

category to SMILE we implemented a reward sys-

tem containing scores, levels, badges, achievements

and a leaderboard. The students can achieve scores

for participating in the live quizzes during the lecture

with additional scores for the correct answer (cf. Fig-

ure 2). A similar score system is applied for repeating

the quizzes outside of the lecture. To prevent students

from getting huge amounts of scores by just repeat-

ing quizzes over and over again, there is a time pe-

riod after each quiz trial in which no further scores

can be obtained. The length of this delay doubles af-

ter each trial. The accumulation of the scores allows

SMILE Goes Gaming: Gamification in a Classroom Response System for Academic Teaching

271

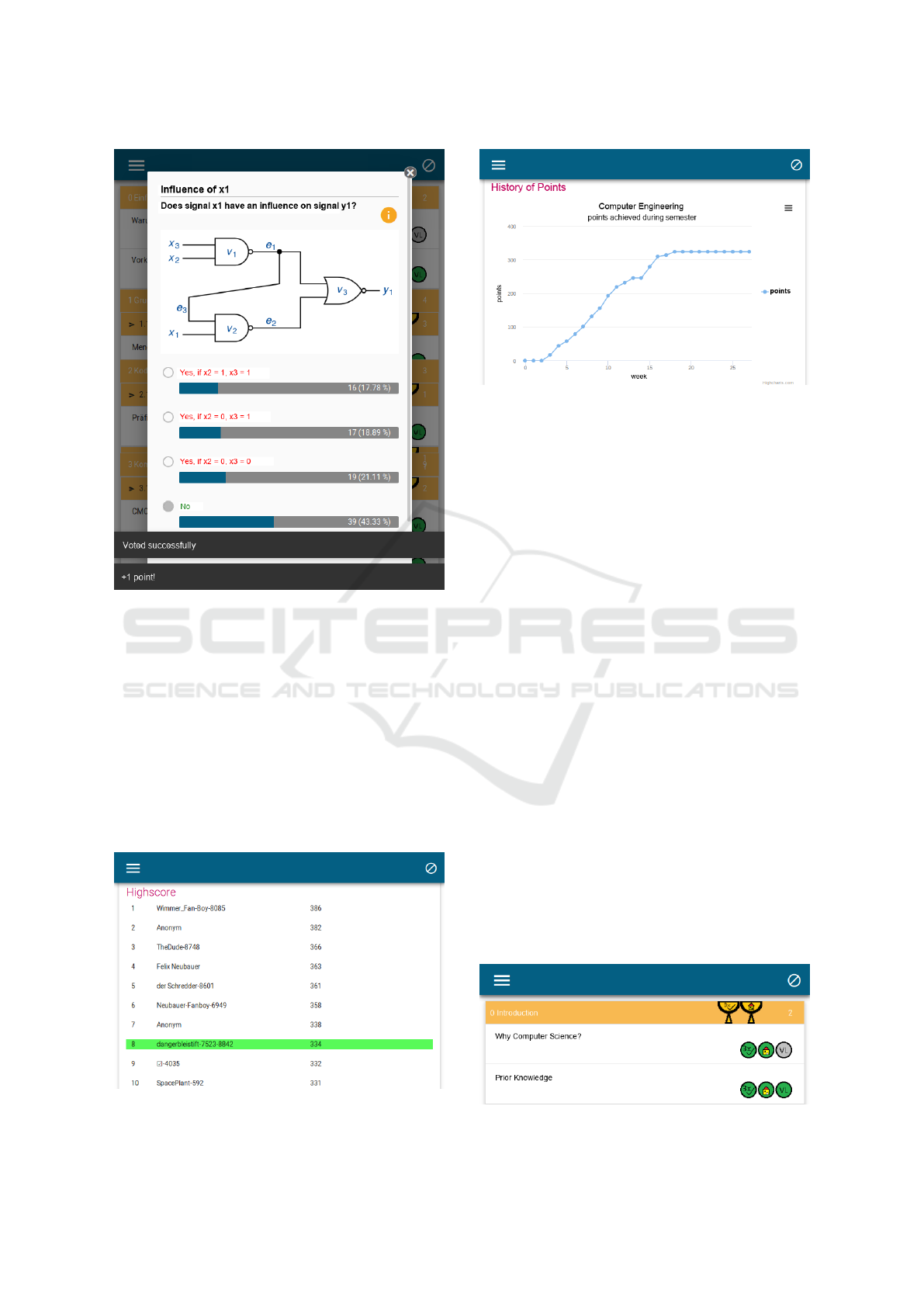

Figure 2: An example of an answered quiz including the

pop-up feedback stating the number of gained scores.

students to gain certain levels and to compare them-

selves with other students via a pseudonym ranking in

a leaderboard which can be seen in Figure 3. Further-

more, each student can follow her/his own progress

over time shown in a score chart (cf. Figure 4).

Students can earn three different badges for each

quiz by answering it (1) during, (2) outside of the

lecture and (3) by giving the correct answer in three

different trials. Collecting one badge category for all

quizzes in a chapter is rewarded by a virtual trophy for

Figure 3: The leaderboard of our course viewed by the

client of a student with “dangerbleistift-7523-8842” as

pseudonym.

Figure 4: A score chart example of a participant of our

course in the winter term 2017/18.

this category in the chapter (cf. Figure 5). Finally, we

also provide some achievements, e.g. for the amount

of answered quizzes, for fast and correct answers or

the amount of quizzes all badges are achieved for.

Empowerment: Challenging and encouraging

the creativity of the user as well as direct feedback

from and to the users are the main goals of the

game elements contained in the empowerment cat-

egory (Chou, 2015). For Opal, Follert and Fischer

(2015) recommend feedback and valuation symbols

e.g. in forums. In SMILE there is already a dedicated

module to give live feedback during the lecture (see

Section 3.1). Furthermore, the Q&A-module is a fo-

rum including different feedback and valuation sym-

bols (e.g. “thumbs-up”) to show that a forum entry

is considered useful. However, as these modules are

not used regularly in lectures, we decided to establish

a sense of empowerment in the Quiz module by giv-

ing direct feedback in form of visual pop-ups in the

user interface. After submitting the answer to a re-

peated quiz students are thus informed about whether

their answer was correct, about the score they gained

as well as the current time delay until scores can be

obtained for repeating this quiz. Such a feedback can

be seen in Figure 2. During live quizzes in the lecture

the information about the correct answer and obtained

scores are not revealed until the lecturer unlocks them,

typically after the discussion.

Figure 5: An example of the students’ overview over all

quizzes with their gained trophies and badges.

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

272

Ownership: The personalisation of the applica-

tion is part of the ownership category (Chou, 2015).

This category is not considered in Opal (Follert and

Fischer, 2015). To provide options for customisation

in SMILE, we introduced the facility for the students

to choose an individual colour scheme for the client

(Figure 2–5 show the blue colour scheme) and to set a

pseudonym which is used in the leaderboard (cf. Fig-

ure 3). If no pseudonym is used, the students remain

anonymous. The pseudonym can be changed and re-

set at any time.

Social Influence: The game elements allowing

interactions with other users are covered by the so-

cial influence category (Chou, 2015). In Opal, this

is solved by chats and a service for private mes-

sages (Follert and Fischer, 2015). In SMILE, mes-

sages can only be exchanged in the Q&A module

which is not used in the considered lecture. How-

ever, the implemented leaderboard covers the social

influence. The board lists the top-ten students, either

completely anonymous or by their voluntarily chosen

pseudonym. Additionally, students can see their own

score for comparison (cf. Figure 3). This ensures that

students are able to compare themselves with the best

ten students even if they do not know who they are.

But the students still have the option to loosen their

own anonymity by using and sharing pseudonyms to

be able to compare themselves with a restricted group

of people, e.g. their friends.

Scarcity: Some game elements (e.g. achieve-

ments) are not supposed to be gained immediately

by the user. Such elements belong to the category

of scarcity. The idea is that the resulting impa-

tience leads to a permanent fixation of the users to the

content, increasing the invested time (Chou, 2015).

Follert and Fischer (2015) used applications such as

showing further education courses (e.g. “Cross mar-

keting”) in Opal to gain scarcity. In contrast, we

achieve scarcity by limiting the scores for repeated

quizzes using an increasing time delay. This ensures

that the high levels cannot be reached too easily. Also

some badges and achievements can only be achieved

over time by e.g. constantly attending the live quizzes

in the lecture.

Unpredictability: The game elements in this cat-

egory are meant to be surprising to the users (Chou,

2015). While there are no unpredictable elements

integrated in the Opal platform (Follert and Fischer,

2015), SMILE implements the concept of unpre-

dictable level names and level-up limits. These pa-

rameters are chosen by the lecturer. The students only

know their current level name and the score neces-

sary to achieve the next higher level. After a level-up

this information is revealed for the new level. As the

transparency of the score and achievement system is

an important aspect in SMILE, we decided to refrain

from further unpredictability.

Avoidance: The avoidance category contains

game elements that motivate the usage of the appli-

cation to prevent negative outcomes (Chou, 2015).

Follert and Fischer (2015) strongly recommend not to

use punishment mechanisms as it can have negative

effects on students’ affection towards learning. We

are also not using punishment of any kind. One could

argue, however, that dropping lower on the leader-

board can be perceived as a negative outcome that ea-

ger students want to avoid by continuously earning as

many scores as possible.

4 EVALUATION

The first prototype of gamified SMILE, including all

game elements described in Section 3.2, was used in

a Computer Engineering course for first semester stu-

dents in the winter term 2017/18. The results from

this extensive field test were then compared to the

previous winter term in which the basic version of

SMILE was used, allowing for a direct comparison

between the basic and gamified versions of SMILE.

In both terms the course was given by the same lec-

turer.

The goal of the evaluation has been to measure

whether the introduced game elements have an effect

on the students’ participation, attention, self-efficacy,

meta cognition, motivation, understanding, and fun.

The effect on the students’ participation is analysed

in Section 4.1 by means of statistical information pro-

vided by SMILE. The evaluation of the other effects

has been done via questionnaires created just for this

purpose. The analysis is described in Section 4.2. We

finally discuss our results in Section 4.3.

4.1 Participation in SMILE

The Computer Engineering lecture under considera-

tion is a course for first semester students with usually

about 250 participants. To be precise there were 266

registrations for the winter term 2016/17 and 248 for

2017/18. From these registrations, 170 took the final

exam in 2016/17, 151 in 2017/18.

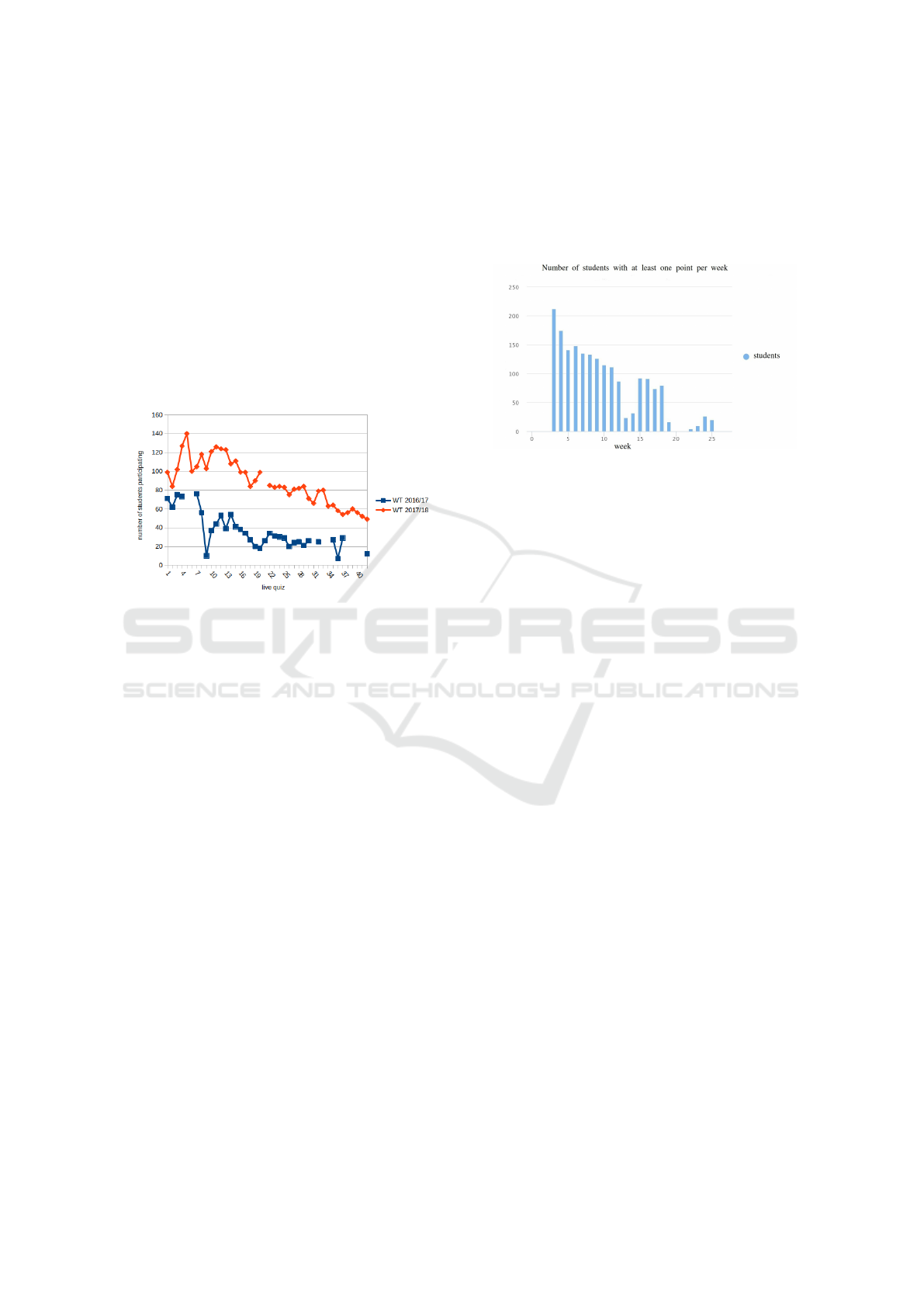

We measured the number of students participat-

ing in each SMILE live quiz during the lectures for

both terms. Figure 6 shows this data in one graph for

comparison. The gaps in the curves stem from sin-

gle quizzes that were used in one term but not in the

other. It can be seen that the number of participants in

2017/18 is on average 2.4x as high as in 2016/17, even

SMILE Goes Gaming: Gamification in a Classroom Response System for Academic Teaching

273

though the number of registered students was almost

equal (even 1.07x lower in 2017/18).

Furthermore, the increased participation rate con-

tinues until the end of the term. When we compare

the average number of participants in the last quarter

of the term (starting with quiz 30) to the maximum

participation in any quiz of the same term, we see that

in 2017/18 there are still 41% (about 58 students) tak-

ing the quizzes, opposed to only 27% (21 students) in

2016/17. When we compare the number of students

still active in the last quarter of the term to the num-

ber of participants in the final exams, the difference is

even higher: more than 38% (of 151) in 2017/18 and

less than 13% (of 170) in 2016/17.

Figure 6: Number of students participating in SMILE

quizzes: winter term 2017/18 (orange) compared to winter

term 2016/17 (blue).

For the winter term 2017/18 we also have ad-

ditional information regarding the general usage of

SMILE provided by the new statistic feature. This

includes that a total of 229 students registered at least

once in SMILE. Figure 7 shows the number of par-

ticipating students per week in 2017/18, either in live

quizzes or repeating quizzes. The statistic accumu-

lates for each week all students who obtained at least

one score in that week. The lecture started in the third

week of the term and lasted until week 19. There were

two courses each week including different numbers

of live quizzes with two exceptions: in week 13 and

14 no lecture took place (Christmas holidays) and in

week 19 there was no live quiz in the lecture. The

final exam took place at the first day of week 26.

Even though the overall participation of students

is sloping during the term (as students drop out of

their studies), Figure 7 shows that at the end of the

lecture (week 18) still about 80 students were using

SMILE. Considering the two outliers in the Christ-

mas break and the time between the lecture and the

exam, up to 32 students used SMILE in their holi-

days and for preparation of the exam. This can be

interpreted as a lower bound for the usage of the post-

processing system of SMILE as in other weeks in-

cluding live quizzes the students might have used this

feature even more extensively. As the post-processing

and the gamification features have been introduced si-

multaneously, it is not possible to evaluate the impact

of gamification on the usage of the post-processing.

Nevertheless, the data shows that this feature is defini-

tively used.

Figure 7: Number of students participating in SMILE by

week in the winter term 2017/18.

All in all, the data shows a significant improve-

ment in the participation numbers from winter term

2016/17 to 2017/18 as well as an active usage of the

new post-processing feature in SMILE.

4.2 Survey Analysis

To measure the influence of gamification on the stu-

dents’ behaviour and learning we designed three eval-

uations: The first one – a pilot survey performed prior

to the first “official” use of gamified SMILE in the

actual course – targeted former participants of basic

SMILE quizzes to attend a contrived lecture asking

for their opinion about the new features. A second one

was handed out in a lecture shortly before the Christ-

mas break and a third one close to the end of term, to

get a final assessment. Every survey was designed as

a paper questionnaire to be answered anonymously.

The questionnaires were all structured as follows:

The first part consisted of several demographic items.

The second part consisted of self-assessment regard-

ing the course itself (irrespective of SMILE) and the

perceived improvement of the lectures by using gam-

ified SMILE. Furthermore, as the students had never

attended a lecture using basic SMILE, they were

asked to estimate the improvements caused by the

gamification or the post-processing feature. The sec-

ond part focused on:

• attention: attentiveness during lecture

• self-efficacy: feeling able to answer exam ques-

tions

• meta cognition: interest in further information

• motivation: motivation to learn and to pay atten-

tion

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

274

• understanding: comprehension of taught content

• fun: enjoyment

• recommendation: suggestion of the use of SMILE

to other lecturers or other students

The third part consisted of questions regarding the

user-friendliness of the web interface while the fourth

part was a section for further comments to not only

get quantitative results but also qualitative answers.

Except for the fourth part all questions were to

be rated with a number between 1 (dislike/not useful)

and 5 (like/useful) or the option to abstain from vot-

ing. If a question was not answered, we considered

it as an abstention from voting. In the following we

define a question as answered positively if the mean

of the given answers is greater than 3, and answered

negatively if the mean is smaller than 3. A positive

outlier is a question with a mean over 4.5, a negative

outlier a question with a mean below 2.

Pilot Survey

The pilot survey

1

was designed to gain user informa-

tion about the effectiveness of the game elements and

of the user friendliness of the web interface to be able

to make adjustments before the actual start of term.

For this purpose the lecturer gave a contrived lecture

for 17 voluntary students on one chapter of the up-

coming Computer Engineering course in which gam-

ified SMILE was used. The participants were after-

wards asked to fill in a questionnaire that also con-

tained questions regarding the understandability of

the questionaire itself. This was to potentially im-

prove the questionnaires of the upcoming two eval-

uations during the term.

Overall, gamified SMILE was rated very posi-

tively (91% positive answers in the questionnaire).

Although the students rated the contrived lecture as

not exciting – not even with gamified SMILE – and

were not motivated to pay attention initially, SMILE

managed to induce certain motivation by the means of

the reward system. The reason for the initial lack of

motivation and excitement though might be that the

lecture was contrived and thus without a subsequent

examination. The participants had a lot of fun using

gamified SMILE and stated that its use (quizzes) was

beneficial for understanding the content of the lec-

ture. Nearly all of them would recommend gamified

SMILE to other lecturers and students (mean value

over 4.5; no single value below 3).

SMILE was considered user-friendly, with some

remarks in the comment section that were taken into

1

Not to be confused with the pre-survey mentioned in

Section 3.2.

account for small adjustments before the actual start

of term, as were comments regarding bugs in the sys-

tem. The other comments were mostly positive, like

some stating they already experienced a positive ef-

fect towards learning. As the understandability of

the questionnaire was evaluated positively (mean over

4.5) we used the same question types in the two other

questionnaires during term.

Mid-term Evaluation

The second evaluation was carried out after two con-

secutive lectures in which even more quizzes than

usual (about five as opposed to the usual one to three)

were performed to focus on the integration of SMILE

into the lecture. 86 first semester students participated

in this evaluation.

The two lectures themselves were perceived pos-

itively in every aspect. The students liked the addi-

tional SMILE quizzes, but were indecisive whether

they gained a benefit compared to the other lectures

with less quizzes. Gamified SMILE was rated posi-

tively regarding attention, motivation, understanding

and fun. The game elements in particular were evalu-

ated as motivating for the usage of SMILE, enhancing

the attention during the lecture and being fun.

As in the pilot survey, the recommendation of

SMILE to other lecturers and students was rated pos-

itively (positive outlier). Also the usability was com-

plimented (positive outlier), especially the quiz func-

tionality and achievement overview.

On the other hand, the self-efficacy and meta cog-

nition for gamified SMILE was rated negatively by

the students. However, this is not very surprising as

the SMILE quizzes only cover the content of the lec-

ture, neither providing exam questions nor further in-

formation. Furthermore, in the students’ opinion the

game elements did not turn out to be useful for the

understanding and motivation to follow the lecture.

The section for further comments contained both

positive and negative comments. While the game el-

ements were mentioned positively, the students com-

plained about bugs in SMILE (that did not occur in

the smaller pilot test group) as well as the WiFi in the

lecture hall and SMILE itself being slow.

Final Evaluation

The last evaluation focused on the use of gamified

SMILE and its post-processing functionality during

the whole winter term 2017/18. 56 students partici-

pated in the survey.

The course itself was again evaluated positively

in every aspect. The evaluations regarding gamified

SMILE as well as the benefit of the game elements

SMILE Goes Gaming: Gamification in a Classroom Response System for Academic Teaching

275

themselves were quite similar to the mid-term evalua-

tion. Once more, attention, motivation, understanding

and fun were rated positively for gamified SMILE.

Also the game elements were seen to be fun and to

motivate the usage of SMILE. However, the influence

of gamification towards attention had shifted from

significant to less significant.

As in both prior surveys the majority of the stu-

dents would highly recommend gamified SMILE to

other lecturers and students. Despite the request of

the students in the pre-survey (cf. Section 3.2) to be

able to repeat SMILE quizzes outside of the lecture,

the post-processing feature – while students were gen-

erally using it – was rated negatively. Questions re-

garding usability were left out in this final evaluation

as no usability adjustments had been done after the

mid-term evaluation that already covered this topic.

In the further comments section the functional-

ity of SMILE was complimented whereas there were

some critics towards SMILE being slow and some mi-

nor bugs. Except for the post-processing feature the

game elements were mostly well perceived.

4.3 Discussion

Observations show that the usage of SMILE is slop-

ing. This has natural reasons as the attendance of stu-

dents in the lectures is decreasing and many students

quit their studies during the term. Nevertheless, we

observed a significant increase of the participation in

SMILE quizzes comparing the winter terms 2016/17

and 2017/18. As there were almost no changes in the

flow of the course (aside from the participating stu-

dents) it is plausible that the increase is induced by

the newly implemented gamification features as well

as the post-processing function in gamified SMILE.

Furthermore, when considering the evaluations,

gamified SMILE turned out to be very useful for

the students’ attention, motivation and understanding.

Figure 8 shows that a majority of the students had fun

using gamified SMILE during the term. Also, many

students stated that the game elements were the main

motivation to use gamified SMILE. But it can be seen

in Figure 9 that this was not true for all students as

a considerable amount of them strongly disagreed or

were just not sure about the impact of gamification on

their motivation. On the other hand, nobody reported

a negative effect of gamification, e.g. distraction from

learning. Furthermore, nearly all students enjoyed the

full “gamified SMILE package”. Thus, we conclude

that the effect of gamification depends on the individ-

ual.

Another aspect to consider is the post-processing

feature. It was highly requested by the students in

Figure 8: Answers of students to the question regarding the

fun they have using gamified SMILE.

Figure 9: Answers of students to the question regarding

their motivation to use SMILE because of the game ele-

ments.

the pre-survey and used even during the holidays.

However, the final evaluation shows that the post-

processing feature is not perceived as helpful by the

students. Nevertheless we see great potential in this

functionality which shall be further explained in the

following final section.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Literature presents gamification as a promising ap-

proach to increase the motivation of students to par-

ticipate more in lectures, to invest more time into

learning the content of the lecture and to have more

fun learning. To take advantage of this, we included

game elements like scores, achievements, badges

and a leaderboard in our classroom response system

SMILE. Furthermore, we implemented a feature for

students to post-process the lecture’s content by re-

peating the live quizzes of the lecture at home. We ob-

serve that gamification has significant positive effects

on the usage of SMILE in lectures. This increased

usage is desirable since SMILE enables the lecturer

to see which content is already understood and which

topics need further explanations. The self-assessment

in the evaluation also indicates a positive effect on

most students as they have fun and are motivated to

use gamified SMILE.

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

276

The most requested feature of the pre-survey, an

option to answer quizzes outside of the lecture, was

the only aspect that was overall evaluated negatively.

Nevertheless we do not want to discard this idea but

plan on improving this feature by adding a function-

ality for students to submit their own quizzes that can

be accessed and answered by other students. This will

furthermore increase empowerment, ownership and

social influence. This modified feature is planned to

be given a trial in our Computer Engineering course

in the summer term 2019. We will then elaborate

how students perceive this functionality in order to

rate the benefit of such a feature for a classroom re-

sponse system in general. We assume that also the

meta cognition will be improved as the option to cre-

ate own quizzes (for others) might activate the stu-

dents to think outside the box of the course. Further-

more, adding exam-like quizzes by the lecturer or the

teaching assistants (or the students themselves) could

also have a positive effect on self-efficacy.

As students would recommend the gamified

SMILE to other students and other lecturers we can

say that the integration of gamification in SMILE was

useful and well perceived and thus will be used in fu-

ture lectures. Our results thus suggest gamification

to be useful for other classroom response systems as

well.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Special thanks go to Sven Reimer for providing an

enormous knowledge of game elements and to Ralf

Wimmer for beta-testing the new SMILE-version in

his lecture.

REFERENCES

AlMarshedi, A., Wanick, V., Wills, G. B., and Ranchhod, A.

(2017). Gamification and behaviour. In Stieglitz, S.,

Lattemann, C., Robra-Bissantz, S., Zarnekow, R., and

Brockmann, T., editors, Gamification - Using Game

Elements in Serious Contexts, chapter 2, pages 19–29.

Springer, Cham.

Barrio, C. M., Mu

˜

noz-Organero, M., and Soriano, J. S.

(2016). Can gamification improve the benefits of stu-

dent response systems in learning? an experimen-

tal study. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in

Computing, 4(3):429–438.

Berkling, K. and Thomas, C. (2013). Gamification of a

Software Engineering course and a detailed analysis

of the factors that lead to it’s failure. In 2013 Interna-

tional Conference on Interactive Collaborative Learn-

ing (ICL), pages 525–530.

Cheong, C., Cheong, F., and Filippou, J. (2013). Quick

Quiz: A Gamified Approach for Enhancing Learning.

In PACIS, page 206.

Chou, Y.-K. (2015). Actionable Gamification: Beyond

Points, Badges, and Leaderboards. Octalysis Media.

Darejeh, A. and Salim, S. S. (2016). Gamification Solu-

tions to Enhance Software User Engagement—A Sys-

tematic Review. International Journal of Human-

Computer Interaction, 32(8):613–642.

Denny, P. (2013). The Effect of Virtual Achievements on

Student Engagement. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI

Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems,

CHI ’13, pages 763–772, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., and Nacke, L. (2011).

From game design elements to gamefulness: defin-

ing gamification. In Proceedings of the 15th inter-

national academic MindTrek conference: Envisioning

future media environments, pages 9–15. ACM.

Feiten, L., Buehrer, M., Sester, S., and Becker, B. (2012).

SMILE – Smartphones in Lectures – Initiating a

Smartphone-based Audience Response System as a

Student Project. In CSEDU (1), pages 288–293.

Follert, F. and Fischer, H. (2015). Gamification

in der Hochschullehre. Herleitung von Hand-

lungsempfehlungen f

¨

ur den Einsatz von Gamedesign-

Elementen in der s

¨

achsischen Lernplattform OPAL.

In Wissensgemeinschaften 2015, pages 115–124.

Fotaris, P., Mastoras, T., Leinfellner, R., and Rosunally, Y.

(2016). Climbing up the leaderboard: An empirical

study of applying gamification techniques to a com-

puter programming class. Electronic Journal of e-

learning, 14(2):94–110.

Glover, I. (2013). Play as you learn: gamification as a tech-

nique for motivating learners. In EdMedia: World

Conference on Educational Media and Technology,

pages 1999–2008. Association for the Advancement

of Computing in Education (AACE).

K

¨

andler, C., Feiten, L., Weber, K., Wiedmann, M., B

¨

uhrer,

M., Sester, S., and Becker, B. (2012). SMILE - smart-

phones in a university learning environment: a class-

room response system. In 10th International Confer-

ence of the Learning Sciences - The Future of Learn-

ing, pages 515–516. ISLS.

Ohno, A., Yamasaki, T., and Tokiwa, K. I. (2013). A dis-

cussion on introducing half-anonymity and gamifica-

tion to improve students’ motivation and engagement

in classroom lectures. In 2013 IEEE Region 10 Hu-

manitarian Technology Conference, pages 215–220.

Sailer, M. (2016). Die Wirkung von Gamification auf Moti-

vation und Leistung - Empirische Studien im Kontext

manueller Arbeitsprozesse. Springer.

TU Dresden (2017). Learning platform OPAL. https://tu-

dresden.de/studium/im-studium/studienorganisation/

lehrangebot/lernplattform-opal?set

language=en.

Accessed: 2018-11-16.

Wang, A. I. (2015). The wear out effect of a game-based

student response system. Computers & Education,

82:217–227.

Yildirim, I. (2017). The effects of gamification-based teach-

ing practices on student achievement and students’ at-

titudes toward lessons. The Internet and Higher Edu-

cation, 33:86 – 92.

SMILE Goes Gaming: Gamification in a Classroom Response System for Academic Teaching

277