Communicating Learning Analytics: Stakeholder Participation and

Early Stage Requirement Analysis

Filothei Chalvatza

1

, Sokratis Karkalas

1

and Manolis Mavrikis

2

1

Technology, Research and Experimentation Ltd, Hertfordshire, U.K.

2

UCL Knowledge Lab, London, U.K.

Keywords:

Learning Analytics Dashboard Design, Educational Stakeholders, Requirements Elicitation.

Abstract:

This paper reflects on a user-centered design methodology for requirements elicitation at early stages of a

design process for Learning Analytics tools. This methodology may be used as a domain specific instrument

to elicit user perspectives about the communicational aspects of learning analytics dashboards. The focus of

this work is identifying ways to communicate the data analysis findings in a way that is easily perceptible

and facilitates actionable decision making. We present the structure as well as the logic behind the design of

this instrument. As a case study, the paper describes an implementation of this methodology in the context of

school-wide analytics communicating to stakeholders quality indicators through summarising and visualising

data collected through student and parent surveys. We provide high-level and transferable recommendations

derived from the analysis of the workshop with key stakeholders and identify future improvements in our

methodology.

1 INTRODUCTION

Learning dashboards have grown in popularity over

the past few years and are becoming a mainstream

tool for monitoring and decision making. While peo-

ple are using them to address real world problems,

there is little evidence that these dashboards convey

the right information to stakeholders and reflect those

burning issues in a way that facilitates actionable de-

cision making. According to (Schwendimann et al.,

2017), the question of how to present relevant infor-

mation effectively remains largely unresolved.

The core concern of this paper is not ‘what’ to

present but ‘how’ to present it. In our view, this as-

pect is relatively neglected as there is a lot of work

on how to analyse and enhance the data but very lit-

tle work on how to make this data easily understand-

able by end users and usable with very little cogni-

tive load for decision making. While the same view is

being supported by (Davenport and Kim, 2013) and

by others looking at the design of learning analytics

mostly in higher education (Avella et al., 2016; Fer-

guson, 2012; Dawson et al., 2014), this issue is even

more pronounced at K-12 where additional data liter-

acy training needs have been identified (Mandinach

and Gummer, 2016). Research in the field has, with

a few isolated exceptions that we review below, so far

focused on the analytical methods themselves and not

enough on how to communicate the analysis results

effectively. This is predicated on the false assump-

tion that it is enough for the end users to be exposed

to data to be able to make sense and take appropriate

decisions.

A sign of this fallacy can be seen in the Refer-

ence Model for Analytics (Chatti et al., 2012), that

defines the four benchmarks: what, who, why and

how. The latter refers to methods and techniques

about analysing data but fails to address the specific

need for techniques on how to present data and con-

vey the appropriate information to end users. Shifting

from matrixes to dashboards is not enough. We opine

that challenging the way a visualisation is designed

in order to express interesting aspects in a meaningful

way should be in line with the ‘how’ benchmark. An-

other example is the Framework of Characteristics of

Analytics (Cooper et al., 2012). This is an attempt to

describe the ontology behind analytics at a very high

level. One aspect of it is referring to data presentation

and the only level of detail it prescribes is limited to

visual and numerical. There is no reference to forms

of expression that should be used to answer user ques-

tions. In that respect, we are following this work and

we are extending this particular aspect of it to make

it more relevant to what is actually needed in real im-

Chalvatza, F., Karkalas, S. and Mavrikis, M.

Communicating Learning Analytics: Stakeholder Participation and Early Stage Requirement Analysis.

DOI: 10.5220/0007716503390346

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2019), pages 339-346

ISBN: 978-989-758-367-4

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

339

plementations.

A methodology that is specifically developed to

provide a framework for the design of learning ana-

lytics tools is LATUX (Martinez-Maldonado et al.,

2015). This is presented as a systematic workflow

for producing learning analytics tools that are both

technologically feasible and truly underpin the learn-

ing experience. Although this methodology is mostly

intended for learning analytics tools for classroom

awareness, orchestration and for informing pedagog-

ical decisions, rather than institutional-wide analytics

for decision-making at a school level, we consider it a

very useful framework that offers a transferable so-

lution to design such analytics. In that respect we

are inspired by LATUX as we have a common ob-

jective. The part that relates to what we do is the first

two steps of stage 1: “what are the requirements?”

and “what are the unexplored possibilities?”. LATUX

simply mentions requirements elicitation without giv-

ing a workflow for it. This particular step is the con-

tribution of our work. We are focusing on the require-

ments step of LATUX to provide a systematic work-

flow that helps elicit stakeholder requirements and in-

volve them in early stages of the design process in a

meaningful way.

Consequently, the focus of this work is on how to

involve stakeholders at early stages of the design pro-

cess. Our premise is that learning analytics is a com-

municational process whose primary purpose is to

enable and facilitate timely and actionable decision-

making. Therefore, we are focused on stakehold-

ers and are concerned with their preferences, needs,

and requirements with regard to data communica-

tion in terms of meaningful visualisations and action-

able feedback. Our research instrument materialises

through a case study in the form of a requirements

elicitation workshop that investigates ways to com-

municate analysis findings in a simple, easily under-

standable and actionable manner.

2 RELATED WORK

Learning analytics is aimed at a wide range of stake-

holders on both individual and organisational level

(Chatti et al., 2012). Learning analytics stakeholders

can be learners, instructors, teachers, trainers, admin-

istrators, developers, researchers, parents, and gov-

ernment bodies or other policy makers (Khalil and

Ebner, 2015). In the context of this project, poten-

tial stakeholders are people who work in the educa-

tional sector holding a managerial or teaching po-

sition, come into contact with students and can use

the outcome of this project to the benefit of one

or more schools. The fact that learning analytics

has a wide variety of stakeholders leads to chal-

lenges due to individual differences. Focusing par-

ticularly on dashboards as a display that ”aggregates

multiple visualizations of different indicators about

learner(s), learning process(es) and/or learning con-

text(s)” (Schwendimann et al., 2017), the challenge

is that they are created for various audiences and this

affects both their appearance and functionality. The

key advantage of visual displays is the fact that they

present complex concepts in an accessible format and

allow stakeholders to capture vital information easily

and quickly. A learning analytics dashboard is a pow-

erful communication medium that increases aware-

ness, supports reflection, and facilitates decision-

making and intervention (c.f. (Karkalas et al., 2016;

Schwendimann et al., 2017)). (Chatti et al., 2012)

also admit that text, tables of data and other tra-

ditional report methods lag behind dashboards that

utilise user-friendly graphical representations. More-

over, they declare the advantages are not in the dash-

board per se. The key is to use proper visual indica-

tors to effectively go through the objectives of each

project. Similarly, (Davenport and Kim, 2013) over-

stress the importance of the effective findings presen-

tation explaining that problem solving is not the core

of analytical thinking. Problems must be framed cor-

rectly to reflect a relevant context. Then the results

need to be communicated in a manner which facili-

tates correct interpretation and sense-making (Dav-

enport and Kim, 2013; Zowghi and Coulin, 2005).

(Baker and Inventado, 2014) specify that learning an-

alytics is a methodology that extracts actionable infor-

mation. Reporting and theoretical description is not

the end of the learning analytics process as it does not

fulfil its ultimate purpose.

Learning analytics is a scientific field that seeks

and provides answers that lead to practical actions

(Cooper et al., 2012). As such, in our view, action-

able is a word that should be at the core of the na-

ture of learning analytics. Educational stakeholders

leverage learning analytics in order to make rational

decisions and follow a reasonable course of action to

achieve their purpose (Dietz-Uhler and Hurn, 2013).

2.1 Early Stakeholder Design

Involvement

Involving the stakeholders early enough minimises

the risk of failure, improves the usability, and

draws greater understanding from LA interventions

(Dollinger and Lodge, 2018). In the literature there

are several cases where stakeholders are asked to con-

tribute to the improvement of aspects of learning an-

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

340

alytics. There is also a lot educational projects that

follow this approach. The project in (Drachsler and

Greller, 2012) makes use of a survey in order to col-

lect information on stakeholders understandings, ex-

pectations and confidence on learning analytics. An-

other project that captures stakeholders perceptions is

described by (Van Harmelen and Workman, 2012).

Stakeholders completed a survey giving their opinion

about benefits and challenges of applying learning an-

alytics on institutional level. The project presented

in (Ali et al., 2012) involved stakeholders of online

learning as evaluators of a system designed to inform

teachers about students activities and performance.

The project shown in (Mavrikis et al., 2016) de-

scribes the stakeholders contribution in the evaluation

of an assisting tool for teachers. The tool provides

the teachers with visualisations to help them monitor

students activity when they work on an exploratory

learning environment. (Holstein et al., 2017) adopted

a participatory design approach with the aim to design

a dashboard that answers real-time teachers’ needs in

the context of an intelligent-tutoring system. Finally,

the project presented in (Govaerts et al., 2012) in-

volved teachers and students in designed based re-

search iterations to evaluate the effectiveness of vi-

sualisations used to increase awareness and support

self-reflection.

3 METHODOLOGY

To elicit stakeholders’ requirements means to

learn, uncover, extract, surface, or discover their

needs (Hickey and Davis, 2004). The activities

that are involved in this process must allow com-

munication, prioritisation, negotiation, and collabora-

tion (Zowghi and Coulin, 2005). Requirements elic-

itation is a very crucial process that defines the suc-

cess or the failure of the final product (Gottesdiener,

2003). There is a significant number of techniques

that can be used in order to facilitate requirements

elicitation (see examples in (Fernandes et al., 2012;

Nistala et al., 2013; Millard et al., 1998; Hofmann and

Lehner, 2001)).

In this project, the primary technique employed

is a requirements workshop. Complementary tech-

niques are scenario, hybrid personas, and focus

groups. The purpose of the workshop is to present

to the stakeholders alternative ways of presenting and

communicating surveys findings, gather their feed-

back on these and elicit further requirements. The

process to gather the desired information is to elabo-

rate on existing data communication models, propose

alternative models, and give the ability to stakehold-

ers to express their preferences, thoughts, and sug-

gestions on them. The following section provides a

detailed step-by-step presentation of this process.

3.1 The Instrument

The instrument is structured as follows:

Scenario: The first step utilises the requirements elic-

itation technique of scenario or use case. In this part

the participants are given the following scenario: You

work for a secondary school in London. For the past

four years the Ofsted rating for your school is Good.

Last year the new school governors launched a se-

ries of actions for school improvement. One of these

actions is to use a survey to take students feedback on

certain aspects of the school life. The survey was com-

pleted by the students at the end of the school year. A

commercial partner has undertaken the survey data

processing and the findings presentation through vi-

sualisation dashboards. Now, it is your turn to see the

dashboards and take the information you need. The

aim of the scenario is to stimulate the participants in-

terest, to help them situate themselves in a real con-

text, and to put the early prototypes in a context of

use.

Hybrid Personas: For the second step the partici-

pants are asked to complete a fill-the-gaps card (figure

1). They have to consider their real-life roles, to ex-

press the main need they would have had if they were

part of the school presented in the scenario, and to

explain the way they would expect this to help them.

This could be seen as an alternative way to create per-

sonas (Caddick and Cable, 2011) with the partici-

pants emerge themselves in the context of the given

scenario. The card is designed to have a very simple

layout and help the participants to articulate the ele-

ments needed for the exercise. After they complete

the cards, the participants have to present themselves

through the cards to the group.

Figure 1: Fill the gaps card.

Communicating Learning Analytics: Stakeholder Participation and Early Stage Requirement Analysis

341

The aim of this is twofold. Firstly, to implicitly

force the participants to think about and articulate

their primary needs. Secondly, to make all the par-

ticipants aware of the others viewpoints in order to

be able to participate and contribute to the subsequent

discussions.

Current Model: For this part we present a dashboard

that is fairly representative of the current model used

for learning analytics. In our case we used a com-

mercial platform provided by a company the name of

which will not be revealed for confidentiality reasons.

The goal of this process is to provide stakeholders

with easily perceptible information allowing them to

focus on specific areas that need improvement.

The participants are asked to explore the com-

pany platform and answer four questions regarding

the effectiveness of the platform. The aim of this is

the participants to see the platform not as a presen-

tation but with an exploratory eye, to think about ad-

vantages and disadvantages, to discuss about the pro-

vided services, and to start thinking about alternative

approaches.

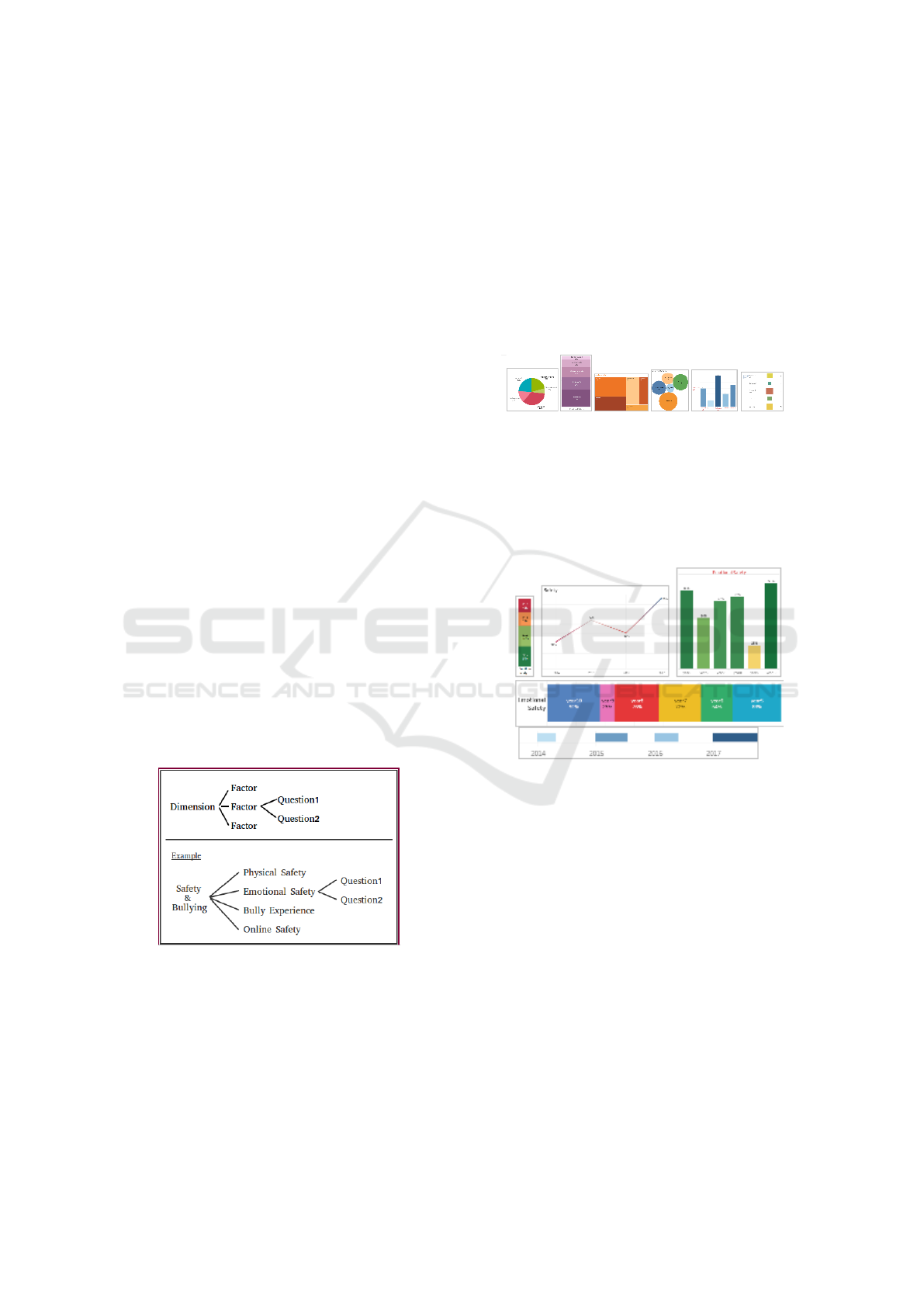

Dimension-factor-Question Scheme: This is in-

tended to discuss alternatives in terms of level of

specificity. This feature is inspired by the Shneider-

man’s Mantra principle “overview first, zoom and fil-

ter, then details-on demand” (Shneiderman, 1996).

As mentioned above, the company’s current data

communication model displays information in two

levels: question and group of questions. Once it is

clear that the stakeholders establish an understand-

ing of this, they are presented the rationale of the

Dimension-Factor-Question Scheme as a principle of

configurability (figure 2). The level of dimension

Figure 2: The Dimension-Factor-Question Scheme.

provides a general overview and informs on general

trends. The level of factor provides a greater level of

granularity and focuses on more specific issues. Fi-

nally, the level of question is optional as sometimes

the user may need to delve into particular questions

whereas other times this may not be necessary. The

presentation is followed by a discussion and feedback

on the scheme.

Evaluation of Alternative Designs: This step is con-

cerned with the evaluation of:

• Alternative designs of individual visualisations on

the level of factor (figure 3). The purpose is to

investigate whether alternative visualisations that

can convey the same messages can be used to

communicate survey findings to the stakeholders

and to see whether certain visualisations are more

popular than others. The visualisations are devel-

oped with Tableau 3.

Figure 3: Visualisations on factor level.

• Visualisations of additional information (progress

and comparison) (figure 4). In this part the stake-

holders are also asked whether they want to see

the full range of the answers or only the positive

(or negative) ones.

Figure 4: Visualisations on Additional Information.

• Visualisations of navigation or organisation of the

data. The purpose here is to elicit stakeholders

preferences regarding the different approaches to

accessing the available information in the dash-

board. The company’s dashboard gives a flat pre-

sentation of all the given questions and the way to

narrow down the information that is presented is

through the use of filters. Alternatively, systems

use menus as navigation tools. There are different

types of menus like flat menus or tree-like menus

that may be used for navigation. For the purposes

of this project there are two interactive menus pre-

sented (figures 5 and 6). These representations -

that also adopt the Mantra’s guidelines- give the

ability to multiple users to view the data on dif-

ferent levels of specificity. For instance, a school

principal would be possibly more interested at

first in school-level data. After the first reading

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

342

of the data, they can drill down to the levels of

subject, teacher, and class in order to obtain in-

formation in more depth. This part attempts to

address the challenging task of satisfying needs

of multiple stakeholders (Siemens and d Baker,

2012).

Figure 5: Interactive Menu 1.

Figure 6: Interactive Menu 2.

The participants are given a series of visualisations

and are told to rate them according to their prefer-

ences (1 - least preferred to 4 - most preferred). Af-

ter that they are given space to write the criteria they

used to rate the visualisations and draw or describe

the ideal visualisation for them.

Evaluation of Additional Information: This step is

also divided into three parts:

The first part seeks answers on both the content

of information as well as the visual representation of

the information. More specifically, it has to do with

the presentation of all the dimensions in a list along-

side the percentage of the positive answers on dimen-

sion level. Proposed visual representations for this

information include dark/light blue thumb-ups and

dark/light red thumb-downs (the answers are divided

in four equal parts), traffics lights (three parts), smi-

ley/sad emoticons (two parts). The second part asks

about the amount of information on the level of factor.

Simply putting it, once the user selects a factor from

the respective dimension they can see only the graph

that corresponds to this particular factor. Additionally

the user can see the progress of the factor over time

and to comparatively look the answers of this factor

on the level of class, teacher, or subject. The third

part is complementary to the second part. It asks the

stakeholders if they want the system to present all the

information in one dashboard (figure 7) or to give the

ability to the user to see one visualisation at a time

using different buttons.

Features for Effective Data Interpretation: The

aim here is to gather stakeholders’ feedback on fea-

tures that may be used to facilitate effective data in-

terpretation without excessive cognitive load. This

includes consideration of colours (one colour, one

colour in different hues, different colours), thresholds

set by the user, banners that briefly describe the visu-

alised information, push notifications (SMS, e-mail)

to the user with worth noting findings, voice chatbots

i.e. Alexa by Amazon, which interacts with the user

and simplifies the presentation of desired findings on

the users screen.

Features for Actionable Decision Making: The fi-

nal step deals with features that may be used to fa-

cilitate actionable decision making. The stakeholders

feedback is required in the following four features:

1. A blank box with a prompt to the user to keep

notes on immediate thoughts

2. Direct question to the user about what they are

planning to do to address possibly problematic

cases

3. A box that contains information on how other peo-

ple usually react to similar cases

4. A drop down window with a list of predefined al-

ternative reactions

4 A CASE STUDY

4.1 Requirements Workshop

The requirements elicitation process took place in the

context of a requirements workshop. The workshop

took place at the UCL Knowledge Lab (London) on

the 2nd of December 2017. It was a 90-minute session

attended by a cohort of seven stakeholders. The group

of participants was fairly diverse as it comprised one

teaching assistant, two teachers (history and ICT), one

Communicating Learning Analytics: Stakeholder Participation and Early Stage Requirement Analysis

343

special educational needs teacher, one school princi-

pal, one school manager, and one member of a school

committee. The diversity among the stakeholders cre-

ated opportunities for stimulating and engaging dis-

cussions. The models presented were seen and evalu-

ated from different viewpoints and that was perceived

as beneficial by the participants. The workshop was

driven by the four general pillars on running work-

shops as they presented by (Lys

´

en, 2003). The pillars

suggest that the workshop must be built on partici-

pants experience and understanding, the aims need

to be understandable by all the participants, the lan-

guage used has to be adjusted to the participants level,

and all the participants must be involved and have op-

portunities to talk and participate. Following these

rules proved to be a challenge especially when par-

ticipants were approaching things from quite diverse

viewpoints.

The methodology of the workshop is an adapta-

tion of the SCRAM (Sutcliffe and Ryan, 1998). The

workshop was organised as a series of eight phases

that took place in a linear manner. The structure

of each phase follows the scheme “presentation, fo-

cus group discussion, summarisation through writ-

ten feedback”. These scheme borrows from the task

characteristics technique proposed by (Browne and

Rogich, 2001).

4.2 Findings

The workshop brought to the fore several specific re-

quirements but here we focus on two general require-

ments that could be transferred to other work. The

first is the participants’ need to take answers easily

and quickly without putting effort to interpret the vi-

sualisation of the findings. The second one goes one

step further. The participants require the system to

provide suggestions that assist the decision-making

process. The workshop also facilitated the elicitation

of more specific requirements. According to these re-

quirements:

• The participants would prefer visualisations to

contain simple graphs that provide certain infor-

mation in a straightforward manner. Enhance-

ment of visualisations with additional and assis-

tive indicators should be very careful and limited.

In many cases, the additional information seems

to confuse instead of help.

• They want to see the way a variable moves over

time so that they can be aware of its progress.

They also want to be able to compare analysis re-

sults between entities (schools. classrooms, teach-

ers, subjects). They want this information to be

part of the main visualisation of a variable in or-

der to take the maximum amount of information

at once.

• They need to see a navigation menu -preferably

multidimensional and interactive- in order to un-

derstand the way the information is organised and

access the level of interest easily. For instance, a

teacher might be interested in classroom-level an-

swers, a principal in school-level answers, and a

manager in company-level answers.

• Once they find the organisational level they are in-

terested in, they want to be able to select the level

of specificity, that is the level of dimension, factor,

and question. Configurable presentation of anal-

ysis results enables them to find the information

easily and quickly.

• The system must provide the user with a ”search

engine”. The search engine has to enable the user

to find answers easily and quickly providing them

with the maximum selection of options that can

be combined during the search.

The first four points are in essence agreements,

disagreements, or enhancements on the given proto-

types. These suggestions can be taken into account

and inform the refinement of the prototypes. On the

contrary, the last point needs further discussion as it is

a new idea emerged from the focus group discussions

during the workshop.

5 CONCLUSION

This paper introduces a new instrument that can be

used to elicit educational stakeholder requirements

and inform the design process of learning analytics

tools and dashboards in particular. This instrument

addresses an existing problem and complements other

well-established frameworks and techniques in the

area of learning analytics design. The instrument can

be used to capture their requirements with regards to

communication of learning analytics results to end

users through learning analytics visualisation dash-

boards. Its aim is to explore characteristics of visuali-

sations that help stakeholders firstly access easily the

analysis findings and secondly make well-educated

decisions based on these findings.

The instrument was implemented as a case study

in the form of a workshop. The logic of the work-

shop was to develop early prototypes as demonstra-

tions of various data visualisations and to present

them to stakeholders. The stakeholders’ role was to

look at the prototypes with a critical eye and dis-

cuss the degree that they achieve their purpose as al-

ternative communicational approaches. The design

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

344

of the prototypes was informed by a review on in-

formation visualisation in and on existing visualisa-

tion dashboards. Some features of the prototypes

are borrowed from existing systems whereas others

are developed from scratch. This paper presented a

case study with findings from a stakeholders’ work-

shop that mainly demonstrated the need for visual-

isations that are as simple as possible and provide

the maximum information in easy-to-read interfaces.

While this may be retrospectively expected, the work-

shop emphasised the need for accompanying visu-

alised findings with recommendations that move be-

yond interpretation and help stakeholders make mean-

ingful fact-based decisions. To cover different needs

of teachers, educators and other stakeholders, a learn-

ing analytics system should be flexible to give them

the ability to choose the information they need to see

as well as the depth and the breadth of the information

presented at different levels of granularity.

With the specific design recommendations we are

making above, this work is a step towards an apprecia-

tion that data analysis cannot act alone in fulfilling the

purpose of communication as it may not convey the

intended messages in an actionable manner. While

further work is needed to understand how best to com-

municate learning analytics in a way that helps stake-

holders make the most out of these tools, the work

presented here demonstrates how an appropriate in-

strument can lead to design requirements that reflect

the actual stakeholders decision-making needs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research leading to these results is co-funded

from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research

and innovation programme under grant agreement No

732489. For information about the CRISS project see

http://www.crissh2020.eu/

REFERENCES

Ali, L., Hatala, M., Ga

ˇ

sevi

´

c, D., and Jovanovi

´

c, J. (2012).

A qualitative evaluation of evolution of a learning an-

alytics tool. Computers & Education, 58(1):470–489.

Avella, J. T., Kebritchi, M., Nunn, S. G., and Kanai, T.

(2016). Learning analytics methods, benefits, and

challenges in higher education: A systematic litera-

ture review. Online Learning, 20(2):13–29.

Baker, R. S. and Inventado, P. S. (2014). Educational data

mining and learning analytics. In Learning analytics,

pages 61–75. Springer.

Browne, G. J. and Rogich, M. B. (2001). An empirical in-

vestigation of user requirements elicitation: Compar-

ing the effectiveness of prompting techniques. Journal

of Management Information Systems, 17(4):223–249.

Caddick, R. and Cable, S. (2011). Communicating the user

experience: A practical guide for creating useful UX

documentation. John Wiley & Sons.

Chatti, M. A., Dyckhoff, A. L., Schroeder, U., and Th

¨

us,

H. (2012). A reference model for learning analytics.

International Journal of Technology Enhanced Learn-

ing, 4(5-6):318–331.

Cooper, A. et al. (2012). What is analytics? definition

and essential characteristics. CETIS Analytics Series,

1(5):1–10.

Davenport, T. H. and Kim, J. (2013). Keeping up with the

quants: Your guide to understanding and using ana-

lytics. Harvard Business Review Press.

Dawson, S., Ga

ˇ

sevi

´

c, D., Siemens, G., and Joksimovic,

S. (2014). Current state and future trends: A cita-

tion network analysis of the learning analytics field.

In Proceedings of the fourth international conference

on learning analytics and knowledge, pages 231–240.

ACM.

Dietz-Uhler, B. and Hurn, J. E. (2013). Using learning ana-

lytics to predict (and improve) student success: A fac-

ulty perspective. Journal of Interactive Online Learn-

ing, 12(1):17–26.

Dollinger, M. and Lodge, J. M. (2018). Co-creation strate-

gies for learning analytics. In Proceedings of the 8th

International Conference on Learning Analytics and

Knowledge, pages 97–101. ACM.

Drachsler, H. and Greller, W. (2012). Confidence in learn-

ing analytics.

Ferguson, R. (2012). Learning analytics: drivers, develop-

ments and challenges. International Journal of Tech-

nology Enhanced Learning, 4(5/6):304–317.

Fernandes, J., Duarte, D., Ribeiro, C., Farinha, C., Pereira,

J. M., and da Silva, M. M. (2012). ithink: A game-

based approach towards improving collaboration and

participation in requirement elicitation. Procedia

Computer Science, 15:66–77.

Gottesdiener, E. (2003). Requirements by collaboration:

getting it right the first time. IEEE Software, 20(2):52–

55.

Govaerts, S., Verbert, K., Duval, E., and Pardo, A. (2012).

The student activity meter for awareness and self-

reflection. In CHI’12 Extended Abstracts on Human

Factors in Computing Systems, pages 869–884. ACM.

Hickey, A. M. and Davis, A. M. (2004). A unified model

of requirements elicitation. Journal of Management

Information Systems, 20(4):65–84.

Hofmann, H. F. and Lehner, F. (2001). Requirements engi-

neering as a success factor in software projects. IEEE

software, 18(4):58.

Holstein, K., McLaren, B. M., and Aleven, V. (2017). In-

telligent tutors as teachers’ aides: exploring teacher

needs for real-time analytics in blended classrooms.

In Proceedings of the Seventh International Learning

Analytics & Knowledge Conference, pages 257–266.

ACM.

Karkalas, S., Mavrikis, M., et al. (2016). Towards an-

alytics for educational interactive e-books: the case

of the reflective designer analytics platform (rdap).

In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference

Communicating Learning Analytics: Stakeholder Participation and Early Stage Requirement Analysis

345

on Learning Analytics & Knowledge, pages 143–147.

ACM.

Khalil, M. and Ebner, M. (2015). Learning analytics: prin-

ciples and constraints. In EdMedia: World Conference

on Educational Media and Technology, pages 1789–

1799. Association for the Advancement of Computing

in Education (AACE).

Lys

´

en, A. (2003). Dialogue in pursuit of development–

ngo experiences. Dialogue in Pursuit of Development,

page 96.

Mandinach, E. B. and Gummer, E. S. (2016). What does

it mean for teachers to be data literate: Laying out

the skills, knowledge, and dispositions. Teaching and

Teacher Education, 60:366–376.

Martinez-Maldonado, R., Pardo, A., Mirriahi, N., Yacef,

K., Kay, J., and Clayphan, A. (2015). The latux

workflow: designing and deploying awareness tools

in technology-enabled learning settings. In Proceed-

ings of the Fifth International Conference on Learning

Analytics and Knowledge, pages 1–10. ACM.

Mavrikis, M., Gutierrez-Santos, S., and Poulovassilis, A.

(2016). Design and evaluation of teacher assistance

tools for exploratory learning environments. In Pro-

ceedings of the Sixth International Conference on

Learning Analytics & Knowledge, pages 168–172.

ACM.

Millard, N., Lynch, P., and Tracey, K. (1998). Child’s

play: using techniques developed to elicit require-

ments from children with adults. In Requirements

Engineering, 1998. Proceedings. 1998 Third Interna-

tional Conference on, pages 66–73. IEEE.

Nistala, P., Kummamuru, S., and Narayana, M. (2013). An

approach to understand and elicit requirements using

systemic models: Ensuring a connect from problem

context to requirements. Procedia Computer Science,

16:786–795.

Schwendimann, B. A., Rodriguez-Triana, M. J., Vozniuk,

A., Prieto, L. P., Boroujeni, M. S., Holzer, A., Gillet,

D., and Dillenbourg, P. (2017). Perceiving learning

at a glance: A systematic literature review of learning

dashboard research. IEEE Transactions on Learning

Technologies, 10(1):30–41.

Shneiderman, B. (1996). The eyes have it: A task by data

type taxonomy for information visualizations. In Vi-

sual Languages, 1996. Proceedings., IEEE Sympo-

sium on, pages 336–343. IEEE.

Siemens, G. and d Baker, R. S. (2012). Learning analytics

and educational data mining: towards communication

and collaboration. In Proceedings of the 2nd inter-

national conference on learning analytics and knowl-

edge, pages 252–254. ACM.

Sutcliffe, A. G. and Ryan, M. (1998). Experience with

scram, a scenario requirements analysis method. In

Requirements Engineering, 1998. Proceedings. 1998

Third International Conference on, pages 164–171.

IEEE.

Van Harmelen, M. and Workman, D. (2012). Analytics

for learning and teaching. CETIS Analytics Series,

1(3):1–40.

Zowghi, D. and Coulin, C. (2005). Requirements elicita-

tion: A survey of techniques, approaches, and tools.

In Engineering and managing software requirements,

pages 19–46. Springer.

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

346