mHealth Applications: Can User-adaptive Visualization and Context

Affect the Perception of Security and Privacy?

Joana Muchagata, Pedro Vieira-Marques and Ana Ferreira

CINTESIS - Center for Health Technology and Services Research,

Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto, Portugal

Keywords: mHealth Applications, Human Computer Interaction, Security of Mobile Visualization Design, Adaptive

Graphical Visualization Interface (AGVI), Electronic Health Records (EHR).

Abstract: Through mobile applications, patients and health professionals are able to access and monitor health data. But

even with user-adaptive systems, which can adjust interface content according to individual’s needs and

context (e.g., physical location), data privacy can be at risk, as these techniques do not aim to protect them or

even identify the presence of vulnerabilities. The main goal of this paper is to test with end-users the adaptive

visualization techniques, together with the context where they are used, to understand how these may

influence users’ security perception, and decide which techniques can be applied to improve security and

privacy of visualized data. An online survey was applied to test two different use-cases and contexts, where

traditional access and access using visualization techniques are compared in terms of security characteristics.

Preliminary results with 27 participants show that when accessing personal data from a patients’ perspective,

the context has higher influence in the perception of confidentiality (authorized access) and integrity

(authorized modification) of visualized data while for a health professional’s perspective, independently of

the context, the visualization techniques are the ones that seem to primarily influence participants’ choices

for those security characteristics. For availability (data available to authorized users whenever necessary),

both visualization techniques and context have little, or no influence, in the participants’ choice.

1 INTRODUCTION

Mobile devices like smartphones or tablets are very

useful to support user needs on the move (Burigat et

al, 2008). Due to advancement of technologies such

as computing and memory capability, Global

Positioning Systems or intuitive and tactile graphical

user interfaces, the latest generation of smartphones

are progressively viewed as handheld computers

(Boulos et al, 2011). These improvements on

smartphones can increase the power of visualization

to anytime, anywhere (Chittaro, 2006) to most

computing application areas, such as medicine,

engineering and science. Visualization can make a

wide range of mobile applications more intuitive and

productive by highlighting important aspects and

hiding irrelevant details (Lapin, 2014), but finding the

best solutions and techniques is a constant challenge

(Burigat et al, 2008; Chittaro, 2006). There are

various limitations, the most obvious one being the

small screen size.

Visualization is not only a matter of information

type and content. The way people interact with

interfaces can affect information security and privacy.

One very common example is when users access

personal or sensitive data (e.g., home banking or

personal medical records) on public busy places such

as trains, airports or coffee shops. Anyone standing

behind or beside that user can easily eavesdrop some

or all information. Further, if all required and non-

required (unnecessary) data at a specific moment is

travelling via unsecure communication channels such

as public non-secure Wi-Fi hotspots, those can be

more exposed and easily eavesdropped by attackers.

Adaptive visualization techniques are available to

adapt visualization in small screens (Schwartze et al,

2010), however these were not tested in relation to

security and privacy of visualized data.

The main goal of this paper is to test with end-

users if adaptive graphical visualization techniques,

together with the user’s context of usage (type of

device, location, connection and time), can be applied

to improve security and privacy of visualized data. An

444

Muchagata, J., Vieira-Marques, P. and Ferreira, A.

mHealth Applications: Can User-adaptive Visualization and Context Affect the Perception of Security and Privacy?.

DOI: 10.5220/0007724304440451

In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2019), pages 444-451

ISBN: 978-989-758-372-8

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reser ved

online survey was applied to test two use-cases where

traditional access and access using those adaptive

visualization techniques are compared in terms of

security characteristics. Further, these are also

analysed in two different scenarios.

2 ADAPTIVE GRAPHICAL

VISUALIZATION INTERFACE

(AGVI)

This paper focuses on identifying the importance of a

user-adaptive system where graphical interface and

information visualization can be adapted to support

users showing detailed results for a specific situation

according to their individual needs (Lapin, 2014;

Schwartze et al, 2010; Yelizarov and Gamayunov,

2014). Traditionally, information visualization

systems ignored user’s needs, abilities and

preferences and followed a one-size-fits-all model

(Steichen et al, 2013). Ideally, visualization

techniques must take into account users’

characteristics such as type of device, location, type

of connection, time as well as security aspects.

Usually the mobile screen has limited space, and thus

it is a challenge to identify how much and what

information should be displayed, what the user really

needs to see and find a convenient way to present it.

A significant effort has been made to study different

representations and navigation techniques, especially

for large documents which are used in desktop

systems (Lapin, 2014). A few studies (Burigat et al,

2008; Chittaro, 2006; Lapin, 2014) have shown

techniques to adapt solutions originally designed for

desktop, namely (Muchagata and Ferreira, 2018):

Restructuring of the information space - this

method transforms a multi-column layout into a

one-column layout; in some cases, the

navigation structure may change significantly

and it may be difficult for users to take full

advantage of their experience.

Scrolling and panning techniques - the space is

scrolled horizontally and vertically and also part

of the space is panned out in any direction; the

screen contains part of the information space.

Zooming - effective method to scale the

information space and can be used to get several

perspectives; objects can change size and shape

or they can appear and disappear from the

visualization space when zoomed.

Overview and detail approaches - provides two

simultaneous views, one for context and one for

detail; the context view highlights part of the

displayed space in the detail, with a rectangular

viewfinder.

Focus and context approaches - the best

example of this technique is the fish-eye view

which increases objects of the user’s focal

attention and gradually decreases the size of

more distant objects.

Each of these methods has advantages but at the

same time may be related to security problems. The

three main security characteristics: Confidentiality,

Integrity, Availability (CIA) can be compromised in

some situations.

3 METHODS

In order to demonstrate the application of AGVI, two

use-cases are presented where it is compared two

different situations and analyse how the user and

context characteristics (e.g., physical location) can

influence the way information is visualized and the

level of security in a specific moment. AGVI

techniques are used from the recommendation list

previously synthesized by two of the authors

(Muchagata and Ferreira, 2018). The visual/graphical

interface is adapted to the specific needs,

characteristics and context of the user during

visualization in real-time. In addition to the visual

part, the information content available is also

dependent on the characteristics mentioned above.

The use-cases are based on two fictional mobile

Electronic Health Records (EHR) apps. In Use-Case

A, the user is a patient who needs to visualize health

records at a pharmacy using a mobile device with the

app MyHealth. Use-Case B describes a mobile app

called iMedicine used by a doctor when searching for

her patients’ records (Sub-section 3.1). The authors

conducted an online survey to verify the perception

of security within the presented scenarios (Sub-

section 3.2).

3.1 Use-Cases

3.1.1 Use-Case A

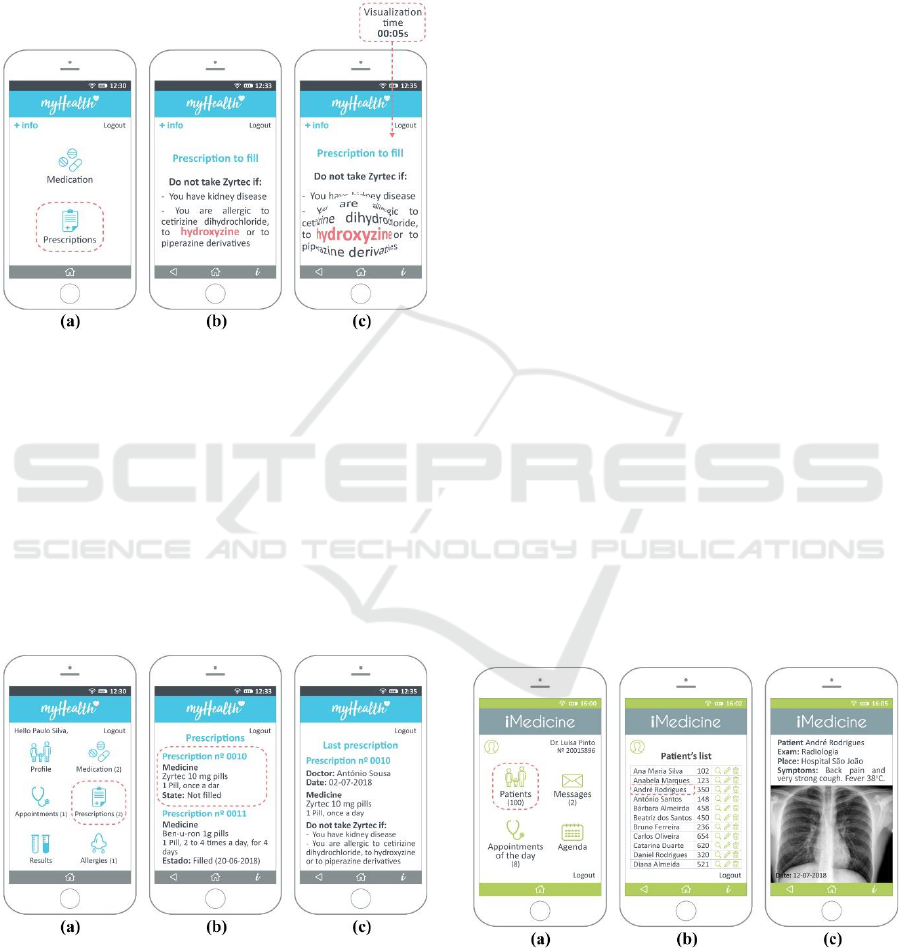

Paulo is a patient and he is at a pharmacy during lunch

time but there is a very long queue. While he is

waiting, he is using his smartphone and trying to sign

in through the app where he has the information about

mHealth Applications: Can User-adaptive Visualization and Context Affect the Perception of Security and Privacy?

445

all his medical records, including medication,

appointments, prescriptions, lab results and allergies.

He needs to see in the system the last prescription

made by his doctor to check for allergies to a specific

medication (Figures 1 and 2) (Muchagata and

Ferreira, 2018).

Figure 1: Before using the AGVI, Paulo, the patient, is able

to see everything available about his medical records

without considering all the involved risks.

The mHealth app analyses Paulo’s characteristics:

device (smartphone), location (pharmacy/public

place), connection (public open Wi-Fi) and time

(lunch time). Paulo connects to the pharmacy free Wi-

Fi network so he does not need to authenticate. This

is considered to be a high security risk connection. As

Paulo is in a pharmacy the system only provides the

items related with “Medication” and “Prescriptions”

(Figure 2).

Figure 2: After using the AGVI the app shows information

according with user’s characteristics and needs with

improved visual security.

If for some reason Paulo needs more information

he can access it through the icon on the upper left

corner “+info”. When he chooses the option

“Prescriptions” the system shows him the most recent

one. At this stage, visualization techniques from

Section 2 are applied. The technique Restructuring

of the information space can be used to adjust the

information content to the smartphone’s screen space.

Also, Focus and context approaches, the fish-eye

technique, is available. This is useful if Paulo needs

to see part of the information in more detail. But at

the same time, it can also increase the risk of

“shoulder surfing” and compromise confidentiality.

Thus, when using the fish-eye technique the system

uses a timer for restricting the duration of zooming

moments in contexts of high security risk (in

this case, 5 seconds). Therefore, if the time is limited,

the risk of privacy and security exposure will be

reduced.

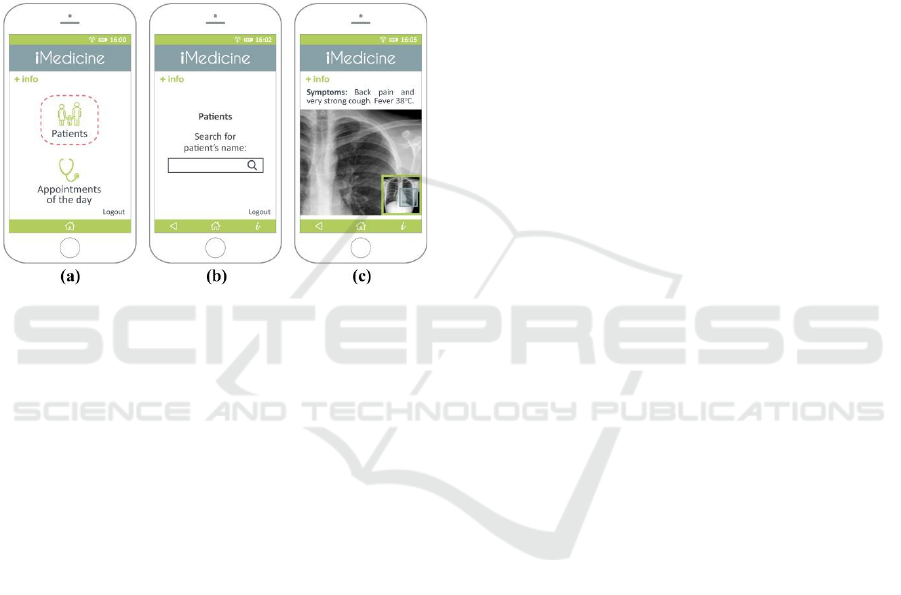

3.1.2 Use-case B

Dr. Luísa is a medical doctor at Hospital de São João

in Porto. After her shift she goes to a coffee shop to

meet a friend around 4pm. Already in the place she

receives a call from a co-worker with some doubts

about a patient. Her colleague needs help to confirm

some diagnostic in an x-ray exam. Dr. Luísa has her

smartphone with her so she accesses the app with her

doctor’s credentials. She is using the free Wi-Fi

network from the coffee shop so it is a high security

risk connection. She signs into the app and she

searches for the patient’s exam result. Again, without

the AGVI she is able to see everything: her profile,

her patients, messages, appointments of the day and

her agenda. After choosing the patients’ icon she can

see the list of all her patients and select the patient she

needs to see the exam (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Before using the AGVI Dr. Luísa is able to see

everything about her profile, patient’s information,

messages, appointments and agenda.

On the other hand, with AGVI, the visualization

and related security are different. In this case Dr.

ICEIS 2019 - 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

446

Luísa just sees two menu icons and if she chooses the

“patients” option (for security purposes), she needs to

type the patient’s name. Then it is possible to see the

exam with no other identifiable patient information to

protect their privacy (Figure 4). In this case, a

visualization technique from Section 2 is also applied.

The technique Overview and detail approaches is

used to highlight a specific part of the exam that was

mentioned by her colleague (third image right in

Figure 4). At all times she can access more detailed

information by selecting the “+info” icon (Muchagata

and Ferreira, 2018).

Figure 4: After using the AGVI, the app shows information

according to user’s most common accessed contents (e.g.

patients and appointments of the day), user’s characteristics

and needs, together with improved visual security.

3.2 Exploratory Tests

The type of test most appropriate for this study, at this

stage, is the exploratory test because it is often

conducted as a comparison test by comparing two or

more designs, such as two different interface

scenarios, to see which has the greatest potential with

our target group (Rubin and Chisnell, 2008).

The main goal is to understand and evaluate the

target opinions in terms of the advantages and

disadvantages of different designs regarding the

confidentiality, integrity and availability of

healthcare sensitive data. The authors intend to

analyse which alternative is the favourite one and,

possibly, the factors associated to this choice.

Thus, an online survey was organized through

the LimeSurvey website and due to the nature of

the study the authors selected a convenience sample

more targeted to an academic group. The survey was

made available during the month of August and

beginning of September of 2018. The use-case

images are in English (Sub-section 3.1) but they were

translated to Portuguese because the survey was taken

in Portugal. The online survey was structured into

four parts:

Part 1 - Free and informed consent to

participate in this study

Description of the study and goals, average of

duration time and information about

confidentiality and anonymity.

Part 2 - Demographic data

Year of birth; Gender; Academic skills;

Occupation; Use of smartphones and mobile

applications in healthcare; Privacy and security

in mobile healthcare applications.

Part 3 - Scenarios (Use-case A and B)

Scenario 1 (Use-case A) corresponds to a

patient’s perspective and it is divided in two

parts. Each part is composed by three pairs of

images and each pair comprehends one “before”

using the AGVI and one “after” using the AGVI

(e.g., Figure 1 (a) is paired with Figure 2 (a);

Figure 1 (b) is paired with Figure 2 (b), and so

on). In the first part the identification of the

context is not present and in the second part the

context is identified (e.g., Figure 1 (a) is paired

with Figure 2 (a) and the user is accessing the

app at Home; and Figure 1 (a) is paired with

Figure 2 (a) while the user is accessing the app

at the Pharmacy).

In its turn, scenario 2 (Use-case B) is the

doctor’s perspective and it is very similar to

scenario 1 but with different images’ content

and contexts (home and coffee shop).

The idea in both scenarios is to analyse the

participants’ perspective about which of the two

images guarantees the highest degree of the

three main characteristics of security:

confidentiality, integrity and availability.

Part 4 - Final observations

Space where participants can leave comments

and opinions about the survey’s content.

For the statistical treatment of the data SPSS

Statistics version 24 was used.

mHealth Applications: Can User-adaptive Visualization and Context Affect the Perception of Security and Privacy?

447

4 RESULTS

Our survey was answered by 27 individuals, aged

between 18 and 45 years old, with the majority of

participants (67%) between the age of 18 and 30 years

old and 33% between 31 and 50. The sample

consisted of 11 males and 16 females. The majority

of participants have higher education n=24 (89%) and

in terms of professional occupation they were

organized as follows: students and researchers n =13

(48%), senior technicians n=5 (19%), health

professionals n=5 (19%) and others n=4 (15%). This

last group includes people who are retired,

unemployed, or people who didn’t specify their

occupation.

Due to the generalization of smartphones and the

variety of applications available today, through the

survey the authors tried to analyse how people use

smartphones and mobile applications in healthcare.

Therefore, and according with our results to the

question “How often do you use a smartphone?”, the

majority of participants n=24 (89%) uses a

smartphone on a daily basis; n=9 (33%) revealed that

they never use mHealth apps and just n=1 (4%) uses

those apps several times a day.

The answers related with the question “How often

do you allow the applications you install to access

your contacts, photos, location, and other personal

information?” revealed that most of them allow it to

happen: n=6 (22%) chose the option “Sometimes”,

n=8 (30%) said “Very often” and n=5 (19%) allow

this to “Always” happen. Only a minority of n=3

(11%) said that they never allow this to happen. This

minority was composed by n=2 (7%) males and n=1

(4%) female; n=2 (7%) between 31 and 50 years old

and n=1 (4%) between 18 and 30 years old; n=2 (7%)

senior technicians and n=1 (4%) in the others group.

Regarding the degree of importance given to

privacy and security in mHealth applications, the

following question was presented to our participants:

“In your opinion, how important is privacy and

security in mHealth applications?”. The answerers of

our participants were “Important” with n=2 (7%),

“Very important” with n=13 (48%) and “Extremely

important” with n=12 (44%).

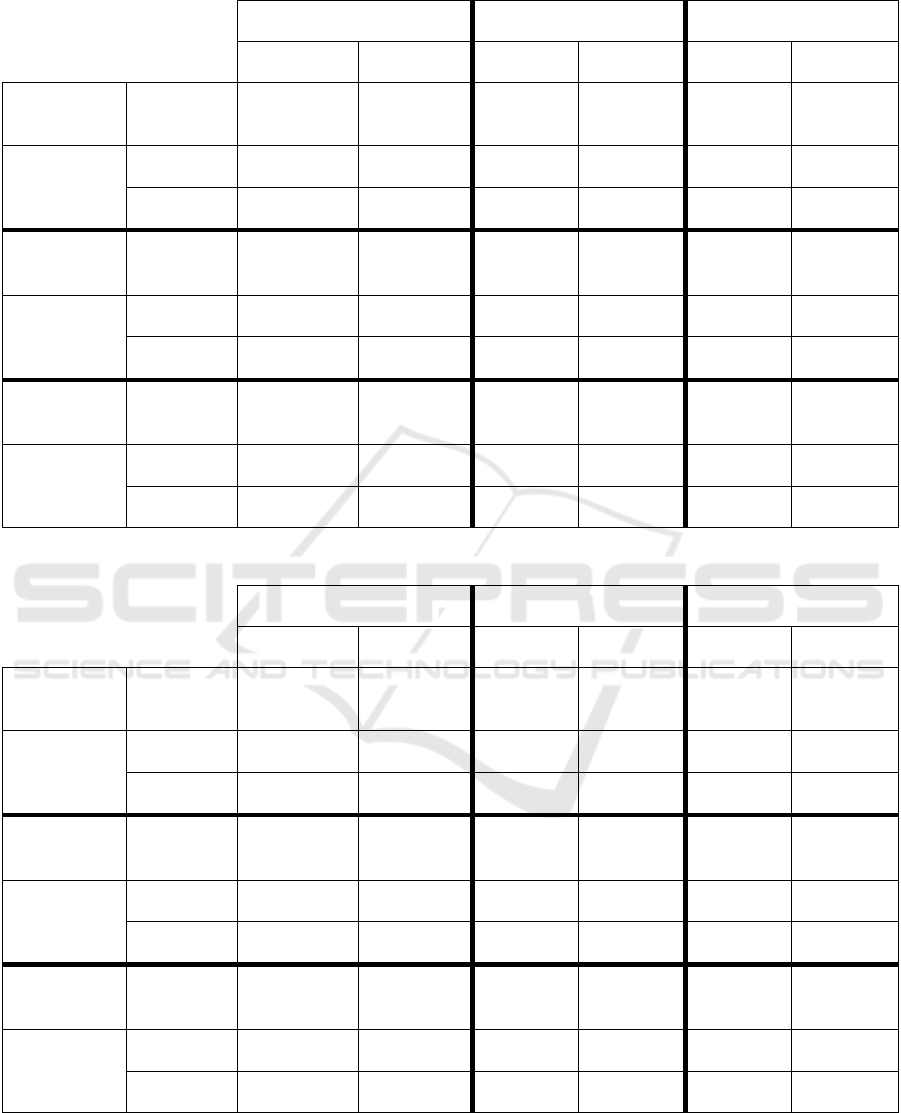

Tables 1 and 2 show the opinion of our

participants related with confidentiality, integrity and

availability. The definitions used for these terms were

as follows:

Confidentiality - The access to information is

exclusively limited to authorized persons and

entities.

Integrity - Information should only be

changed/modified by authorized persons or

entities.

Availability - Information must be accessible to

authorized persons whenever necessary.

Tables 1 & 2 are organized as follows: “Screen”

corresponds to the type of content visualized by the

participants in each pair of images (one without

AGVI – “Figure 1” and the other with AGVI –

“Figure 2”, “Menu” is the application menu;

Sensitive data - technique 1 and 2 correspond to the

visualization techniques applied in each case;

“Context of usage provided” refers to the analysis of

the images in the first place without context “No” and

in second place with context “Yes”; “Figure 1”

represents the figures with all the content available

independently of the user’s characteristics (type of

device, location, connection and time), and “Figure

2” includes the figures with the visualization

techniques applied and so the user can just see what

is relevant at that specific moment.

Regarding Patient Data (Table 1), and beginning

with the analysis of confidentiality, the participants

select “Figure 2” as being the one that ensures a

higher degree of confidentiality. When presenting the

same images accompanied by context (“Figure 1” -

home and “Figure 2” - pharmacy) small differences

could be noticed, however “Figure 2” remains in

participants’ opinion as the one that offers a greater

degree of confidentiality. In terms of integrity, Image

2 is mostly chosen independently from the context,

apart from Figure 2 (a) – Menu, that is less chosen

when the context is present. In the case of availability,

“Image 1” was chosen by all (independently of the

context) as the one that shows more availability of

patient data.

In its turn, and in the doctor’s scenario, Table 2

demonstrates that “Figure 4” guarantees a higher

level of confidentiality when compared with “Figure

3”. Relatively to the integrity of data, most

participants chose “Figure 4”, apart from Figure 4 (a)

– Menu, the most chosen for integrity with context

but less chosen when context is not present.

Regarding data availability, as it happens for the

patient’s perspective scenario, “Figure 1” is always

considered as the one which offers more availability

of patient data.

ICEIS 2019 - 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

448

Table 1: Scenario 1 – Patient’s Perspective (confidentiality, integrity and availability).

Confidentiality

Integrity

Availability

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 1

Figure 2

Screen

Context of

usage

provided

Fig. 1 (a)

Fig. 2 (a)

Fig. 1 (a)

Fig. 2 (a)

Fig. 1 (a)

Fig. 2 (a)

Menu

No

9 (33%)

18 (67%)

9 (33%)

18 (67%)

24 (89%)

3 (11%)

Yes

6 (22%)

21 (78%)

15 (56%)

12 (44%)

24 (89%)

3 (11%)

Screen

Context of

usage

provided

Fig. 1 (b)

Fig. 2 (b)

Fig. 1 (b)

Fig. 2 (b)

Fig. 1 (b)

Fig. 2 (b)

Sensitive

data

technique 1

No

7 (26%)

20 (74%)

13 (48%)

14 (52%)

22 (82%)

5 (19%)

Yes

10 (37%)

17 (63%)

17 (63%)

10 (37%)

23 (85%)

4 (15%)

Screen

Context of

usage

provided

Fig. 1 (c)

Fig. 2 (c)

Fig. 1 (c)

Fig. 2 (c)

Fig. 1 (c)

Fig. 2 (c)

Sensitive

data

technique 2

No

5 (19%)

22 (82%)

15 (56%)

12 (44%)

23 (85%)

4 (15%)

Yes

9 (33%)

18 (67%)

15 (56%)

12 (44%)

24 (89%)

3 (11%)

Table 2: Scenario 2 – Doctor’s Perspective (confidentiality, integrity and availability).

Confidentiality

Integrity

Availability

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 3

Figure 4

Screen

Context of

usage

provided

Fig. 3 (a)

Fig. 4 (a)

Fig. 3 (a)

Fig. 4 (a)

Fig. 3 (a)

Fig. 4 (a)

Menu

No

8 (30%)

19 (70%)

12 (44%)

15 (56%)

22 (82%)

5 (19%)

Yes

13 (48%)

14 (52%)

18 (67%)

9 (33%)

22 (82%)

5 (19%)

Screen

Context of

usage

provided

Fig. 3 (b)

Fig. 4 (b)

Fig. 3 (b)

Fig. 4 (b)

Fig. 3 (b)

Fig. 4 (b)

Sensitive

data

technique 1

No

3 (11%)

24 (89%)

8 (30%)

19 (70%)

15 (56%)

12 (44%)

Yes

3 (11%)

24 (89%)

11 (41%)

16 (60%)

18 (67%)

9 (33%)

Screen

Context of

usage

provided

Fig. 3 (c)

Fig. 4 (c)

Fig. 3 (c)

Fig. 4 (c)

Fig. 3 (c)

Fig. 4 (c)

Sensitive

data

technique 2

No

2 (7%)

25 (93%)

9 (33%)

18 (67%)

21 (78%)

6 (22%)

Yes

5 (19%)

22 (82%)

10 (37%)

17 (63%)

19 (70%)

8 (30%)

mHealth Applications: Can User-adaptive Visualization and Context Affect the Perception of Security and Privacy?

449

5 DISCUSSION

Our study shows the complexity in analysing various

variables connected with human behaviour. The

authors addressed issues such as perception of

security and privacy, adaptable visualization as well

as the context to try to understand the best way to

provide data in mobile applications. Following a

previous work (Muchagata and Ferreira, 2018) where

a set of visualization techniques were analysed in

terms of their potential effect on the confidentiality,

integrity and privacy of mobile data content, this

study advances the state of the art by exploring how

the perceptions of real users are affected depending

on the content and on the adoption of visualization

techniques to present that content to the user.

Regardless if the participants represent doctors or

patients (or even both), the authors considered

relevant and appropriate to know their opinions and

perspectives when they place themselves in both

scenarios.

For the patient’s scenario, and in terms of

confidentiality, every time a particular context is

presented, some participants change their opinion on

what image’s content provides a higher degree of

confidentiality. Commonly in the first image

regarding the menu selection, participants change

their opinion to think that confidentiality is higher

when choosing from a menu when they are at a

pharmacy than when they are at home. Maybe this is

explained by the fact that the type of data they are

accessing relates to health information, which can be

commonly more sensitive. However, when asked the

same question regarding the third image which

includes the results of their search, when the context

is presented, participants change their opinion that

Figure 1 (the one with more personal data content), at

home, is the most secure in terms of confidentiality.

This may be because this information is more related

to the patient’s personal (specific medication) data

and so visualizing this data at home can certainly feel

more secure and trustworthy.

In terms of integrity, for the same patient’s

scenario, answers reveal that there is a big change for

the menu image when there is no context and when

the context is present. Participants favour Figure 2

(the one with less content and visualization

techniques) without the context, but once the context

is presented they change their opinion to favour

Figure 1 (the one with more detailed content and

without visualization techniques) that is viewed at

home. The same happens to the subsequent image

where content is searched. Regarding integrity, the

most chosen secure visualization content is the one

with more detail and viewed at home. What are the

factors that trigger this change? The authors believe

that since integrity is at stake, the more information

and detail available from the searched content, the

better (although this can be confused with

availability) but is not the same for the steps that lead

to search for that data, such as in choosing from

menus. For all options regarding integrity, being at

home is considered safer and more trustworthy than

in a public place.

In terms of availability, participants’ responses

are very consistent and do not change whether context

is present or not. This is also true for the doctor’s

scenario. The visualization content mostly chosen for

availability is Figure 3, which understandably always

comprises the most detailed and complete data, even

though in some cases it could not be considered the

most secure option.

In relation to the doctor’s scenario, there are some

differences in terms of confidentiality. In this case,

there is no variation in the participants’ choice as

Figure 4, the ones with the applied visualization

techniques (and therefore with less and more focused

content), are always chosen. For the doctor’s scenario

the context does not interfere with the perception of

security and privacy unless the content is the menu of

choices (the first image in the sequence), so for all

others it seems that the applied visualization

techniques have, alone, an impact in that choice. For

integrity in this same scenario, there is a similar

change from Figure 4 to Figure 3 for the menu option,

but here, for the other two images, the most chosen

ones in the doctor’s scenario are the ones with

visualization techniques, and not the ones with more

detailed content, as for the patients’ results. There are

just small variations when context is present. Again,

it seems apparent that when a health professional is

accessing confidential data the perception of security

for the surveyed participants is that patient data

should be more controlled and contained than when it

is a patient accessing that data, even if that access is

performed at a public place, such as a coffee shop.

Here the context “home” is not the one providing a

higher sense of trust and integrity, visualization

techniques seem to override that.

Limitations. Despite encountering a few examples of

the use of adaptive visualization techniques in mobile

applications, the authors could not find a clear and

detailed methodology and procedures that could help

with their implementation in practice, especially

within the fields of security and privacy. Also, this

study had time and management constraints with the

application of the online questionnaire within the

ICEIS 2019 - 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

450

holiday period, the month of August and beginning of

September, and the change of questionnaires

appliance in relation to the new European legislation

regarding personal data, which is for the moment

halted by the University management. Therefore, the

authors had a small turnover of responses and a small

sample to analyse and were not able to adequately

compare results with demographic variables.

Also, for the analysis of the doctor’s perspective, only

a small part of the participants were health

professionals (n=5 – 19%). As such, it can be harder

for a non-health professional to evaluate how a

certain system and related sensitive data content must

or not be protected.

However, these constitute preliminary results that can

be further detailed with a wider application of the

same questionnaire, as it is ready for use, as soon as

management constraints are lifted. The authors

believe that these are important first steps in

understanding the subject at hand. For being small,

the sample is not varied in participants’ background

or age but balanced in terms of gender.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This study provides a first overview on the influence

that context and adaptive visualization techniques can

have on the users’ perception regarding security and

privacy of mHealth applications. Due to the

complexity of human behaviour and human computer

interactions, more focus on this line of research is

needed.

The authors conclude that both context and

adaptive visualization techniques can influence

mHealth users’ perspectives on security and privacy

but add also that, consequently, the roles (e.g., patient

or health professional) and goals (e.g., searching for

a medication or a patient and analyse exams) used to

interact with the applications can also come into play

and add to the complexity and relevance of this

subject.

With this in mind, a more complete/detailed

analysis and with a wider and more diverse sample

needs to be performed to better understand the factors

and requirements to design more secure and privacy

compliant mHealth applications.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This article was supported by FCT through the

Project TagUBig - Taming Your Big Data

(IF/00693/2015) from Researcher FCT Program

funded by National Funds through FCT - Fundação

para a Ciência e a Tecnologia.

REFERENCES

Boulos, M. N. K., Wheeler, S., Tavares, C. and Jones, R.

(2011) How smartphones are changing the face of

mobile and participatory healthcare: an overview, with

example from eCAALYX. BioMedical Engineering

OnLine, 10, 24-24.

Burigat, S., Chittaro, L. and Gabrielli, S. (2008) Navigation

techniques for small-screen devices: An evaluation on

maps and web pages. International Journal of Human-

Computer Studies, 66(2), 78-97.

Chittaro, L. (2006) Visualizing information on mobile

devices. Computer, 39(3), 40-45.

Lapin, K. (2014) Visualization Approaches for Mobile

Devices, In Proceedings of the 11th International

Baltic Conference. Baltic: Databases and information

systems.

Muchagata, J. and Ferreira, A. (2018) How Can

Visualization Affect Security?, ICEIS 2018 - 20th

International Conference on Enterprise Information

Systems. Poster Presentation in Funchal, Madeira -

Portugal: SCITEPRESS Digital Library.

Rubin, J. and Chisnell, D. (2008) Handbook of Usability

Testing: How to Plan, Design, and Conduct Effective

Tests, 2 edition. Wiley Publishing, Inc.

Schwartze, V., Blumendorf, M. and Albayrak, S. (2010)

Adjustable context adaptations for user interfaces at

runtime, Proceedings of the International Conference

on Advanced Visual Interfaces. Roma, Italy, 1843051:

ACM, 321-324.

Steichen, B., Carenini, G. and Conati, C. (2013) User-

adaptive information visualization: using eye gaze data

to infer visualization tasks and user cognitive abilities,

Proceedings of the 2013 international conference on

Intelligent user interfaces. Santa Monica, California,

USA, 2449439: ACM, 317-328.

Yelizarov, A. and Gamayunov, D. (2014) Adaptive

Visualization Interface That Manages User's Cognitive

Load Based on Interaction Characteristics, Proceedings

of the 7th International Symposium on Visual

Information Communication and Interaction. Sydney

NSW, Australia, 2636844: ACM, 1-8.

mHealth Applications: Can User-adaptive Visualization and Context Affect the Perception of Security and Privacy?

451