The ICT Literacy Skills of Secondary Education Teachers in Greece

Vyron Ignatios Michalakis, Michail Vaitis and Aikaterini Klonari

Department of Geography, University of the Aegean, University Hill, 81100, Mytilene, Lesvos, Greece

Keywords: ICT Literacy, Secondary Education Teachers, Mobile Learning, Greece.

Abstract: This article discusses the ICT literacy of secondary education teachers in Greece. Regardless of their specialty,

a representable sample of 700 in-service teachers from 283 secondary education schools throughout Greece,

participated in our questionnaire survey that was conducted from December 2017 until June 2018. The

teachers were questioned about their familiarity with personal computer and smartphone use, whether they

use ICT devices in the classroom, while also reporting any obstacles they face in order to implement ICT in

the educational process. The data collected enabled us to review the teachers’ ICT literacy. The ICT literacy

definition we endorse is the one offered by ETS (Educational Testing Service) (2007); “ICT literacy is using

digital technology, communications tools, and/or networks to access, manage, integrate, evaluate, and create

information in order to function in a knowledge society”. The findings of the research showed that the majority

of Greek teachers are skilled ICT users, embracing their implementation in their teaching interventions,

although ICT related Greek policies are contradictory.

1 INTRODUCTION

The importance of digital literacy is well

acknowledged around the world as progressively

more countries adopt ICT (Information and

Communications Technology) policies in education

(UNESCO, 2011). The infusion of ICTs in schools,

that mostly took place in the early 90s, failed in its

early stages to revolutionize education (Cuban, L.,

2000, 2001), as in most cases technology was adapted

to traditional school structures, classroom

organization and existing teaching practices (Dakich,

E., 2015). As of now educators have realized that in

order to impact student learning, ICT must be

integrated by teachers that are digitally literate and

understand how to integrate it into the curriculum.

According to the European Commission (2013)

“teachers’ confidence in using ICT can be as crucial

as their technical competence, because confidence

levels can have potential influence on the frequency

with which teachers use ICT-based activities in the

classroom”.

In this article, we survey a representative sample

of 700 secondary education teachers in Greece, in

order to evaluate the Greek education system’s ability

to adopt ICT, based mainly on teachers’ ICT literacy.

Numerous frameworks have been published about the

proper definition and meaning of digital and ICT

literacy. Ng, (2012), considering all existing

definitions, stated that digital literacy has three

dimensions, depending on the exact skills required;

technical, cognitive and socio-emotional. The

technical dimension involves possessing the technical

and operational skills to use ICT for learning and in

everyday activities, the cognitive dimension as the

ability to think critically in the search, evaluate and

create cycle of handling digital information, and the

socio-emotional as being able to use the internet

responsibly for communicating, socializing and

learning. Many researchers list digital literacy as one

of the 21st century skills (Vavik and Salomon., 2015)

(Voogt et al., 2013) (Trilling and Fadel, 2009) but

Trilling & Fadel also described ICT literacy as a part

of digital literacy. Specifically, they grouped the 21st

century skills into three main areas; Learning and

innovation skills, digital literacy skills and career and

life skills. They later divided the digital literacy skills

in information literacy, media literacy and ICT

literacy. The following ICT literacy definition was

offered in 2007 by ETS (Educational Testing

Service); “ICT literacy is using digital technology,

communications tools, and/or networks to access,

manage, integrate, evaluate, and create information in

order to function in a knowledge society “.

Summarizing, digital literacy is a more broadband

term than ICT literacy, and includes the skills

376

Michalakis, V., Vaitis, M. and Klonari, A.

The ICT Literacy Skills of Secondary Education Teachers in Greece.

DOI: 10.5220/0007728703760383

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2019), pages 376-383

ISBN: 978-989-758-367-4

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

required to be able to critically evaluate and impart

information, retrieved using ICT.

ICT training programs for teachers in Greece are

divided into two levels. The A-lever training

curriculum is about acquiring basic knowledge and

skills in the use of ICTs in education. The curriculum

covers introductory concepts of computer science and

basic usage of personal computer, use of word

processor, spreadsheets and presentation software as

well as connection and communication over the

internet. It also deals with the acquisition of some

basic knowledge for the adoption of ICTs in the

educational process by using educational software

products (

Greek Ministry of Education, Pedagogical

Institute, 2005)

. The A-level training program was later

followed by the more advanced B-level ICT teacher

training that addressed basic specialty teachers;

Philology – Language, Mathematics, Physical

Sciences, Informatics, Primary education and

Kindergarten teachers. Today the B-level program

has been totally redesigned and is composed by two

(sub-)levels of knowledge and skills: a. “Introductory

training for the utilization of ICT in school” (B1-

Level ICT teacher training, 36 teaching hours) and b.

“Advanced training for the utilization and application

of ICT in the teaching practice” (B2-Level ICT

teacher training, 42 teaching hours and additional 18

hours for preparing “in-class practice”). The

combination of these two levels equals to the

acquisition of knowledge and skills corresponding to

the integrated training for the utilization and

application of ICT in the teaching process (B-level

ICT teacher training) (

Computer Technology Institute

and Press “Diophantus” CTI, 2016). The B1 as well as

the B2 level programs are also divided in clusters,

depending on the specialty of the teacher. The first

A-level ICT training program for teachers In Greece,

took place between 2001 to 2005 with 83,315

participant teachers and a total budget of 89,661,162

€ (

Greek Ministry of Education, Pedagogical Institute,

2005).

Today, the ICT teacher training program is still

very famous among teachers. Indicatively the last B1-

level program that started in May 2017 and is

scheduled to end in February 2019 has already 24,281

participating teachers.

Based on the above our main hypothesis was that

Greek teachers would be very familiar with using

computers as well as the internet, although it was

unclear as to what extend they use the computer for

educational purposes. Furthermore, a relatively new

parameter that is often ignored when talking about

ICTs in education, are the smart mobile devices

(smartphones and tablets) that are nowadays the most

common means to conduct mobile learning activities.

As far as mobile phones are concerned, we also

expected that teachers would be very familiar with

them and various smartphone applications, as nearly

every mobile phone sold today is “smart”. In order to

examine their pc and smartphone-related skills, as

well as whether mobile devices have penetrated the

Greek schools and to what extent, we used a

questionnaire that consisted of two main parts, one

personal computer and one mobile device-related.

2 METHOD

2.1 The Questionnaire

In order to collect the research data, we created a pilot

questionnaire that was distributed to secondary

education teachers located in the island of Lesvos,

Greece. That questionnaire did not only contain

closed-ended questions but also some open-ended

ones. For instance, teachers were asked to describe

the reasons why they would not use an educational

smartphone application in the context of an

educational activity. The most popular answers were

later transferred in the questionnaire that was finally

used for this research (see appendix), that only

consists of closed-ended questions. The questionnaire

consisted of four parts. The first part contained the

participants’ descriptive data, the second part was

titled “familiarity with personal computers” and

contained seven questions, the third part was titled

“familiarity with smartphones and tablets” and

contained five questions. The fourth and last part of

the questionnaire was titled “Geocaching” and will

not be examined in this article, as we mainly focus on

the ICT literacy of the participants.

2.2 The Participants

Based on the total population of 68,139 secondary

education teachers in Greece and 75 directorates of

secondary education throughout the country, we

targeted a less than 2% error margin. In order to

achieve that we used a 7.55% percentage on the

overall population that resulted in a total of 544

required sample of teachers. We also ensured that our

sample would be representative by calculating the

exact number of responses required by every region.

The questionnaire was sent to hundreds of secondary

education school all over Greece. As a result, the total

number of participants reached 700 from 283

secondary education schools from every region of

Greece (Figure 1).

The ICT Literacy Skills of Secondary Education Teachers in Greece

377

Figure 1: The location of every school that participated in

the survey.

The collected data about the participant teachers

(their age and specialty, as well as information about

their school; whether it is a gymnasium, lyceum or

vocational lyceum and its location) are presented in

Table 1.

Table 1: Survey Demographics.

School

Gymnasium Lycium

Vocational lycium

51.79% 32.71% 15.49%

Specialty

Mathemati-

cal and

Physical

Sciences

Languages

and

Philologi-

cal

Sciences

Informa-

tion and

Computer

Sciences

Engienner-

ing

Sciences

Other

Courses

28.19% 33.77% 18.36% 4.11% 15.57%

Age

23-35 36-50 51+

5.31% 57.53% 37.16%

2.3 Data Analysis

Every question was treated as a single categorical or

ordinal variable, depending on the type of question

and possible responses. For categorical responses,

frequencies and percentages were calculated and the

responses were cross-tabulated to check for statistical

significance with the Chi-square test. For ordinal

variables, descriptive statistics and Spearman linear

correlations were calculated. Before the analysis of

data, we checked the responses for internal

consistency with the use of cross-tabulations between

pre-determined sets of questions that would reveal if

the respondents were consistent in their responses and

therefore if the particular sets of responses would be

used in the overall analysis. These consistency

questions included checking if the responses that

referred to frequency of use of devises – software

were consistent with later responses. SPSS 23 was

used for the analysis.

3 FINDINGS

The following descriptive statistics are presented

either by text, charts or tables and provide an

overview on how much teachers use ICT either for

personal or educational use.

3.1 Descriptive Statistics – Personal

Computers

Out of 700 teachers only 1.1% (8 teachers) answered

that their school does not provide access to a personal

computer, while 99.3% of those enjoying pc access

also have access to the internet. In their personal life

most of the teachers use a computer and the internet

daily. When asked whether they use it for education

purposes (lesson preparation or in-class use), only

2.4% answered “never”. In order to discern the exact

web applications that they use as well as the skills

required, the participants replied on how often they

use certain popular education-related web

applications (Table 2). In comparison with more

popular, globally recognized applications such as

google forms, dropbox etc. the one that Greek

secondary education teachers use the most is

Photodentro (

Greek Ministry of Education, Pedagogical

Institute, 2005

). Photodentro is the Greek National

Learning Object Repository (LOR), and hosts

publicly available reusable learning objects such as

educational videos and software, user generated

content (UGC) and open educational practices

(OEPs).

Although not as popular as Photodentro, “e-me”

is a digital educational platform for pupils and

teachers (Megalou et al., 2015). E-me was created in

order to become the personal working environment

for every pupil and teacher, safe place for

collaboration, communication, sharing of files and

utilization of digital content, a space for the social

networking of pupils and teachers, framework for the

integration and operation of external apps and a space

where the work of pupils, teachers and schools can be

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

378

Table 2: Web Application Usage Frequency.

Never

%

Rarely

%

Freque

ntl

y

%

Daily

%

Total

%

Forums

(N=480)

41,5 32,5 22,3 3,8 100

E-class

(N=521) 33,2 30,5 31,1 5,2 100

Dropbox

(N=516)

27,1 36,2 30,4 6,2 100

Google drive

(N=563)

16,7 23,1 46,4 14 100

Google forms

(N=497) 34,6 30,4 31,2 3,8 100

Geocaching

(N=442)

90,3 7,7 1,8 0,2 100

GoldHunt

(N=438)

96,1 3,2 0,7 100

Mobilogue

(N=438) 95 4,3 0,7 100

Google Earth

(N=538)

20,6 47,8 29,7 1,9 100

e-me (N=434) 87,6 8,5 3,2 0,7 100

Photodentro

(N=625)

10,7 29,4 54,4 5,4 100

Geogebra

(N=478)

72 13,8 13,2 1 100

made public and showcased (e-me Digital

Educational Platform, 2018)

Although, based only on the above table one can

get an image of what specific tasks are the teachers

able to perform, on a separate question, participants

were asked what specific tasks they feel more familiar

with. The teachers present themselves as very

familiar various tasks, such as registration and login

in various platforms/websites, emails and file

uploading, and less but still on a satisfactory level,

with map usage and cloud operations (Table 3).

Table 3: Web Application Related Skills.

Skills

Never %

Rarely %

Freequently %

Daily %

Total %

Register/login

(Ν=693)

3,6 13,9 41,1 41,4 100

Maps (Ν=689) 9,1 25,7 43,3 21,9 100

File uploading

(Ν=688)

6 19,6 38,1 36,3 100

Cloud apps (Ν=665) 23 24,4 26,8 25,9 100

email (Ν=694) 1,6 3 29,8 65,6 100

3.2 Descriptive Statistics – Smart

Mobile Devices

The third part of the questionnaire focused on

teachers’ familiarity with smart mobile devices such

as smartphones and tablets. Furthermore, we survey

whether smartphones have found their way through

Greek secondary schools, the educators’ views about

their use in the educational process and the obstacles

that prevent them from implementing mobile learning

technics. Educational applications for smartphones

thrive nowadays (Michalakis et al., 2017), (Kohen-

Vacs, D., et al., 2012), as the multifaceted benefits of

mobile learning are now acknowledged by the

educational community (Mehta R, 2016), (Taylor,

J.K., et al., 2010).

62.75% of teachers use a smartphone or a tablet

daily while a 18,77% frequently. At the same time

8.45% of the participants reported that they never use

smart mobile devices.

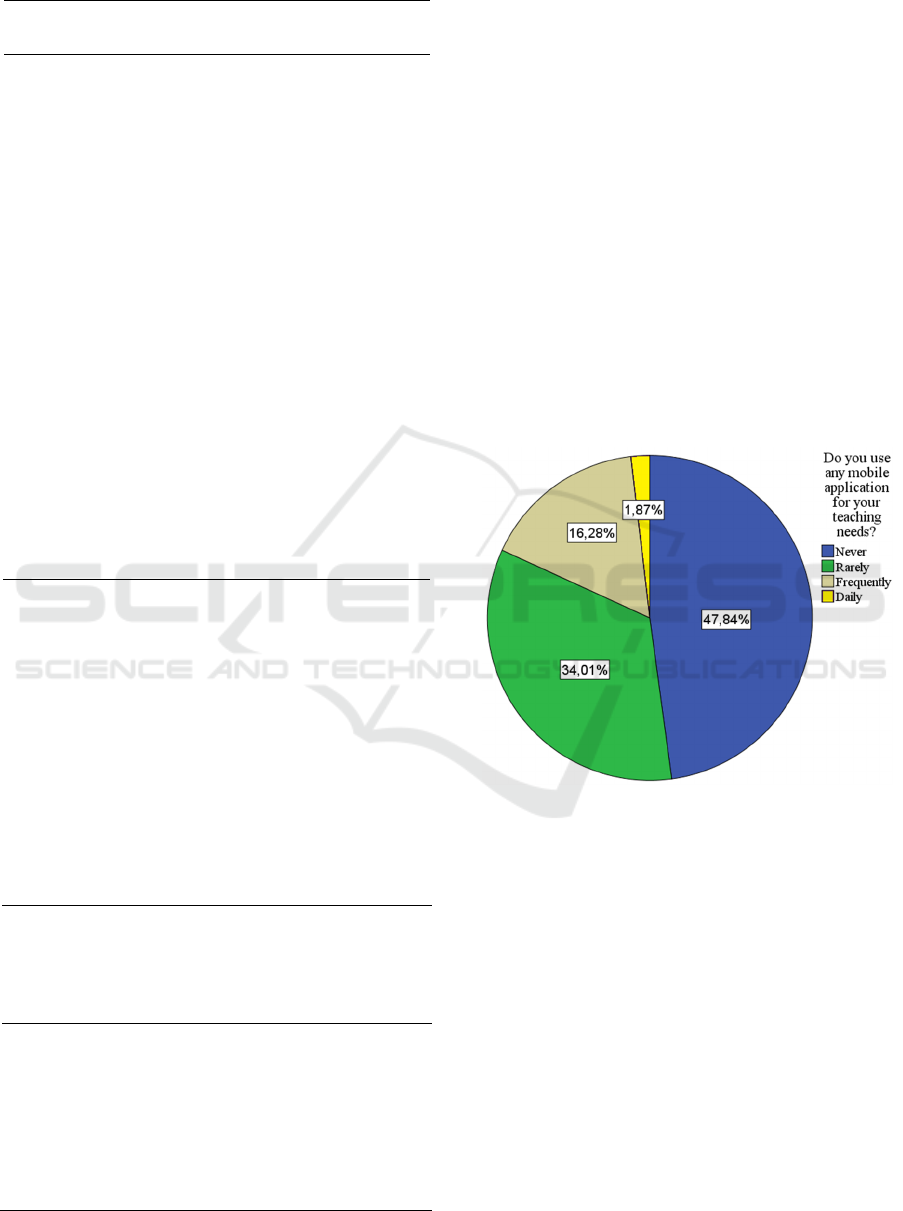

Figure 2: Smart Mobile Device Usage in School.

As to what kind of mobile applications teachers

feel more familiar with, a worth mentioning result is

that 24.5% report fully accustomed with mobile

educational application while 43.3% are “quite

familiar”. Also, the small percentage of teachers that

are not accustomed to educational apps at all, 10.3%,

is an encouraging sign regarding the future of mobile

learning.

Regardless of the familiarity of teachers with

educational applications, do they use mobile devices

for their teaching needs? The pie chart presented in

Figure 2, suggests not, as 47.85% of the participants

have never used educational mobile application, and

at the same time 34.01% only rarely.

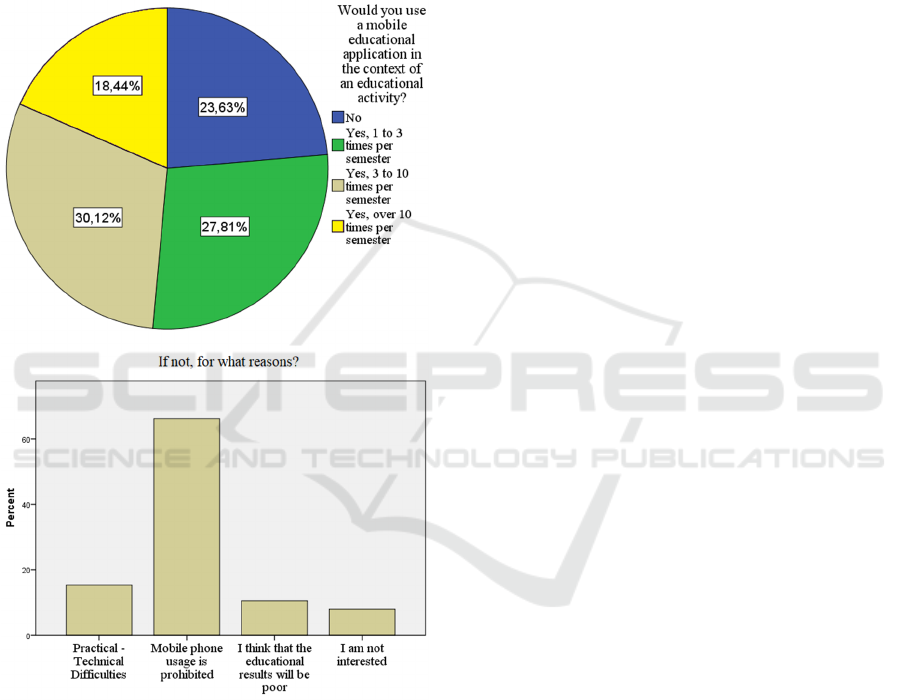

Interestingly, contrary to that pie chart, 81.56% of

participants reported that they would use a mobile

The ICT Literacy Skills of Secondary Education Teachers in Greece

379

educational application in the context of an

educational activity. Furthermore, an impressive

18.44% would use a mobile application more than 10

times per semester, and 30.12% 3 to 10 times per

semester (Figure 3). An explanation for that contrast,

between real and hypothetical implementation of

mobile learning technics can be seen in Figure 3,

where 66.3% of the teachers report prohibition of

mobile devices in schools as the most common reason

why they would not implement mobile learning.

Figure 3: Intention and Obstacles for Mobile Learning

Implementation.

The prohibition of mobile devices in Greek schools is

a topic that will be discussed later in this article, as

possible existence of such prohibition is against the

Greek National Digital Educational Policy, that

promotes ICT in primary and secondary education

(Megalou and Kaklamanis, 2014). At the same time,

possible ignorance of the teachers on the subject

would reveal a simple but also fundamental

malfunction of the country’s education system.

3.3 Statistically Significant Findings

The following findings are the results of an extensive

cross tabulation analysis of the collected data.

Statistically significant are considered only the

findings with a calculated chi-square pi value lower

than 0.05. The two main axes that we will examine

are ICT experience and age.

One of the research findings is that frequent and

experienced everyday computer or smart mobile

device users are also more frequent and more willing

computer or smartphone users for educational

purposes. The analyzes that led us to the above are the

following;

More frequent everyday PC use – more

educational use of PCs;

More frequent internet use – more educational

use of PCs. pi = 0.0002;

More frequent everyday smart mobile device

use – more educational use of PCs. pi =

0.0000027;

More frequent everyday PC use – more willing

to use educational mobile apps in school. pi =

0.002;

More frequent everyday smart mobile device

use – more willing to use educational mobile

apps in school. pi = 3*10

-10

(Table 4);

More frequent everyday smart mobile device

use – more frequent educational use of smart

mobile devices. pi = 25*10

-17

;

More familiar with various mobile applications

– more willing to use educational mobile apps

in school. In all cases pi < 0.05;

More familiar with various mobile applications

– more frequent educational use if smart mobile

devices. In all cases pi < 0.05;

Less frequent everyday PC use – less interested

in mobile learning. pi = 0.004;

Less everyday smart mobile device use – less

interested in mobile learning. pi = 0.044;

The last two observations also confirm the above

finding from an opposite perspective; Non or not

frequent PC or smart mobile device users, are not

interested in applying mobile learning techniques in

their teaching interventions. The above statistically

significant findings confirm that teachers need to be

fully accustomed with the tools they use and therefore

reassuring the need for constant ICT training that

includes mobile technology related courses.

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

380

Table 4: Cross-tabulation Analysis; Smart Mobile Device Use and Intention to Conduct Mobile Learning Activities.

Would you use a mobile educational application in the context of an

educational activity

No

Yes, 1 to 3

times per

semester

Yes, 3 to 10

times per

semester

Yes, more than

10 times per

semester

Total

Do you use

smart phones

or tablets?

Never Count 34 11 8 6 59

Expected Count 14 16,4 17,7 10,9 59

Rarely Count 22 22 18 8 70

Expected Count 16,6 19,5 21 12,9 70

Frequently Count 34 46 28 22 130

Expected Count 30,8 36,2 39 24 130

Daily Count 74 114 154 92 434

Expected Count 102,7 120,9 130,3 80,2 434

Total

Count 164 193 208 128 693

Expected Count 164 193 208 128 693

Pearson Chi-Square Test: Value: 63,248a df: 9 pi: 3,2E-10

Table 5: Cross-tabulation Analysis; Teachers’ Age and Educational PC Use.

Do you use a PC for your teaching needs?

Never Rarely Frequently Daily Total

What is your

age?

23-35 Count 2 2 21 12 37

Expected Count 0,9 4 17,9 14,2 37

36-50 Count 5 37 188 169 399

Expected Count 9,8 43,1 193,5 152,7 399

51+ Count 10 36 128 85 259

Expected Count 6,3 27,9 125,6 99,1 259

Total

Count 17 75 337 266 695

Expected Count 17 75 337 266 695

Pearson Chi-Square Test: Value: 14,735a df: 6 pi: 0.022

Another interesting finding of our research

suggests that teachers between 36 to 50 years of age

are more frequent PC users for educational purposes,

pi = 0.022 (Table 5), although younger participants

are more frequent and experienced smartphone/tablet

users. At first, the above finding is surprising, but

given the high unemployment rate of young teachers

in Greece, and the handful of years required in order

to acquire teaching experience, teachers aged

between 36 to 50 are indeed readier to adopt alternate

teaching technics and material.

4 DISCUSSION & CONCLUSION

This research focuses on secondary education

teachers’ ICT literacy and not in-school ICT use. All,

(except one mobile learning activity related),

questions regarding educational use of ICT by

teachers do not provide data about ICT use during the

lesson but indicates how much teachers use ICT

either for lesson preparation or any other teaching

related purpose, regardless of the teaching method

they eventually apply.

Personal computer and internet use percentages

are high amongst Greek teachers, while almost all

schools provide pc and internet access. Meanwhile

during 2018 the Greek ministry of education supplied

many schools with new ICT equipment, indicating

that school equipment may not be as outdated as it

used to in previous years. Also, the vast majority of

teachers use personal computers for educational

purposes and the frequent use of photodentro LOR

indicates that the development of such quality

material is worth it, as teachers acknowledge its

significance.

The ICT Literacy Skills of Secondary Education Teachers in Greece

381

As far as smart mobile devices are concerned,

teachers are also frequent users, while most of them

also report fully accustomed with various tasks. In

comparison with personal computers, mobile devices

are not used for educational purposes yet, although

81.56% of the participants reported that they would

conduct a mobile learning activity multiple times per

semester. Comparing that percentage with the one

that indicates how many of the teachers actually use

a mobile device for educational purposes, 52.36%,

and taking into account the fact that that percentage

does not only represent mobile learning activities but

every education-related use, Greek teachers although

willing, they do not actually embrace mobile learning

in their teaching interventions. An explanation could

be looked for in the reasons why the rest 23.63%

reported that they would never conduct such an

activity (N=163). 66.3% reported that mobile devices

are prohibited in school. Furthermore, in a later

question of the same questionnaire, that is not

considered in this paper, all participants were asked

to report the main factors that should be taken into

account when conducting a mobile learning activity

(N=617). 37.1% of the participants reported the same

prohibition. A simple google search confirmed that

by the time the survey took place (December 2017

until June 2018) mobile phone use by secondary

school students was prohibited, with no exceptions.

In December 2006 the Greek ministry of education

prohibited the use of mobile phones in schools. In

exceptional cases students were allowed to carry their

turned-off phone in their bag. In September 2012 the

same prohibition was also applied to all similar

devices that could record images and sounds, such as

cameras. Since then, the first mobile-learning-

friendly ministerial decision was issued in August

2016 with the subject “Use of Mobile Phones and

Electronic Devices in School Units”. The document

prohibits students carrying mobile phones or “any

other electronic device or game that features an image

and sound processing system within the school space.

Equivalent equipment available to them by the school

they attend is used during the teaching process and

the educational process in general and only under

teacher’s supervision” (Computer Technology

Institute and Press “Diophantus” CTI, 2016). The

document also enables teachers to carry their own

devices for teaching purposes, and it also states that

uploading photos and videos, in which pupils are

depicted, on school websites should be avoided due

to personal data regulations. That circular although

allowing mobile phone use in schools for educational

purposes, was only referring to primary education,

thus retaining previous prohibitions to secondary

education schools, and leaving secondary education

teachers who wanted to apply mobile learning

vulnerable to the law. Eventually in June 22, 2018, an

almost identical circular was forwarded to all

education principles and all primary and secondary

education schools of the country, enabling for the

first-time secondary education teachers to implement

mobile learning technics. Even though such issues

should be addressed long before 2018, our findings

suggest that mobile learning has the potential to thrive

in Greece’s secondary education, for three reasons;

Teachers are willing. Especially if we consider

that the majority of the small percentage of teachers

that would not conduct a mobile learning activity,

reported so because of the until recently mobile phone

prohibition.

Teachers are familiar and skilled smart mobile

device users. As another one of findings suggest,

those are two important conditions that favor the

implementation of ICT in the classroom.

ICT teacher training programs and the general

effort put in the ICT field by the ministry of

education, such as photodentro and e-me are very

promising signs of an educational system that is

willing to adapt to the 21

st

century.

REFERENCES

Computer Technology Institute and Press “Diophantus”

(CTI), 2016. Accessed 11 November 2018, https://e-

pimorfosi.cti.gr/en/the-project/about-b-level-ict-teacher-

training

Cuban, L., 2000. So much high-tech money invested, so little

use and change in practice: How come? Paper presented

at the Council of Chief State School Officers' annual

Technology Leadership Conference in January 2000,

Washington, D.C.

Cuban, L., 2001. Oversold and underused: Computers in the

classroom. Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-

01109-0.

Dakich, E., 2005. Teachers’ ICT Literacy in the

Contemporary Primary Classroom: Transposing the

Discourse. Paper presented at the AARE Annual

Conference. Parramatta 2005. Available at https://

www.aare.edu.au/data/publications/2005/dak05775.pdf.

e-me Digital Educational Platform, 2018. Computer

Technology Institute and Press “Diophantus” (CTI)

Accessed 20 November 2018, https://auth.e-me.edu.gr/

European Commission. 2013. Survey of schools: ICT in

education. Benchmarking access use and attitudes to

technology in Europe’s Schools. Brussels: European

Commission Final report. Available at:

https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/sites/digital-

agenda/files/KK-31-13-401-EN-N.pdf

Greek Ministry of Education, Pedagogical Institute, 2005.

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

382

Accessed 10 November 2018, <http://www.pi-

schools.gr/programs/ktp/epeaek/ergo.html>

Kohen-Vacs, D., Ronen, M., Cohen, S., 2012. Mobile

Treasure Hunt Games for Outdoor Learning, Bulletin of

the IEEE Technical Committee on Learning Technology,

Volume 14, Number 4.

Megalou, E., Kaklamanis, C., 2014. Photodentro LOR, the

Greek National Learning Object Repository.

Proceedings of INTED2014. Publisher: IATED. (pp.

309-319). Retrieved May 6, 2015 from

http://dschool.edu.gr/p61cti/promotion/publications/

Megalou, E., Koutoumanos, A., Tsilivigos, Y., Kaklamanis,

C., 2015. Introducing “e-me”, the Hellenic Digital

Educational Platform for Pupils and Teachers.

Proceedings of EDULEARN15 (pp.4858- 4868).

Mehta, R., 2016. Mobile learning for education – benefits

and challenges IRJMSH Volume 7 Issue 1, ISSN 2277-

9809

Michalakis, V.I., Vaitis, M., Klonari, A., 2017. RouteQuizer

– A Geocaching System for Educational Purposes.

Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on

Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2017) -

Volume 2, pages 367-374. ISBN: 978-989-758-240-0.

Ng, W., 2012. Can we teach digital natives’ digital literacy?

Computers & Education, 59(3), 1065-1078.

Photodentro, 2018. Computer Technology Institute and Press

“Diophantus” (CTI) Accessed 20 November 2018,

photodentro.edu.gr

Taylor, J.K., Kremer, D., Pebworth, K., Werner P., 2010.

Geocaching for Schools and Communities, Human

Kinetics, ISBN-13: 9780736083317.

Trilling, B., Fadel, C., 2009. 21st Century Skills: Learning

for Life in Our Times, Jossey-Bass (publisher),

2009.ISBN 978-0-470-55362-6. Retrieved 2016-03-13

UNESCO, 2011. Transforming education: the power of ICT

policies. ISBN: 9789231042126, Available at: http://

unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002118/211842e.pdf

Vavik, L., Salomon, G., 2015. Twenty first century skills vs.

disciplinary studies. Handbook of Research on

Technology Tools for Real-World Skill Development, 1,

1-12.

Voogt, J., Erstad, O., Dede, C., Mishra, P., 2013. Challenges

to learning and schooling in the digital networked world

of the 21st century. Journal of Computer Assisted

Learning, 29(5), 403-413.

APPENDIX

The questionnaire contained the following questions;

1) In what type of secondary school do you teach?

a) Gymnasium b) Lycium c) Vocational Lycium

2) Where is your school located?

3) What lesson do you teach?

4) What is your age?

a) 23-35 b) 36-50 c) 51+

5) Does the institution you teach, give you access to a

computer?

a) Yes, for teaching only b) Yes, for personal use

c) Yes, for administrative support d) No PC access

6) If yes, does it provide internet access?

a) Yes, for teaching only b) Yes, for personal use

c) Yes, for administrative support d) No PC access

7) Do you use personal computer outside the school for

personal use?

a) Never b) Rarely c) Frequently d) Daily

8) If yes, how often do you use the internet?

a) Never b) Rarely c) Frequently d) Daily

9) Do you use a computer for educational needs? (eg

teaching, lesson preparation etc.)

a) Never b) Rarely c) Frequently d) Daily

10) If yes, which of the following online applications do

you use and how often?

Fora, e-class, dropbox, Google drive, Google forms,

Geocaching, Goldhunt, Mobilogue, Google earth, e-

me, Photodentro, Geogebra / a) Never b) Rarely c)

Frequently d) Daily

11) How familiar are you with the following types of web

applications?

Applications requiring user registration and login,

Applications using maps, Applications for file

uploading, Cloud applications, Email applications / a)

Not at all b) A little c) A lot d) Fully

12) Do you use smartphones or tablets?

a) Never b) Rarely c) Frequently d) Daily

13) How familiar are you with the following types of

mobile applications?

Social media, News applications, Map applications,

Educational applications, Entertainment applications,

Applications using GPS features / a) Not at all b) A

little c) A lot d) Fully

14) Do you use any mobile application for educational

purposes?

a) Never b) Rarely c) Frequently d) Daily

15) Would you use a mobile educational application in the

context of an educational activity?

a) No b) Yes, 1 to 3 times per semester c) Yes, 3 to 10

times per semester d) Yes, more than 10 times per

semester

16) If not, for what reasons?

a) Practical - Technical Difficulties b) Mobile Phones

are Prohibited c) Poor Educational Outcomes d) I am

not Interested

The ICT Literacy Skills of Secondary Education Teachers in Greece

383