Understanding the Correlation between Teacher and Student Behavior in

the Classroom and Its Consequent Academic Performance

Adson R. P. Damasceno, Andressa M. de O. Ferreira and Francisco C. M. B Oliveira

Ceara State University, Av. Dr. Silas Munguba, 1700, Fortaleza, Brazil

Keywords: Education, Student Engagement, Dropout, Classroom Management.

Abstract:

Education in Brazil has reflected in students’ poor academic performance. To reverse this scenario, we propose

a technological ecosystem for classroom management which we call Classroom Management (GSA, acronym

in Portuguese for Gest

˜

ao de Sala de Aula). The technology focuses on increasing teenagers’ performance and

reducing dropout rates. The GSA promotes student engagement in classroom activities; allows the monitoring

of students while performing these activities; creates channels of communication between teacher and student;

automatically addresses the level of understanding of the class; promotes student participation in class discus-

sions. We tested the GSA and got promising results: 1) For more than seventy percent of the students, the use

of technology made them understand the subject better; 2) 85% of them reported that the GSA increased their

participation in the classroom activities; 3) For more than 90% of the students, the class has become more

interesting, and; 4) 88% of them would like to use the system in all disciplines. For teachers, the GSA: 1) Has

not become an object of distraction in the classroom (opinion, 92% of them); 2) It made the students more

participative (89%); 3) It made the class more dynamic (82%) and 4) Would like to use the GSA in all their

classes (81%).

1 INTRODUCTION

According to OECD (2016), In Brazil, about 36%

of 15-year-olds report having repeated their school

year at least once, a proportion similar to that of

Uruguay. Among Latin American countries that par-

ticipated in the International Student Assessment Pro-

gram (PISA) in 2015, only Colombia has a higher

school dropout rate, around 43%. Countries with poor

performance in PISA and higher levels of social in-

equality in school are more prone to such rates of

school repetition.

Students need to be motivated to learn. OECD

(2016) distinguishes two forms of motivation to learn

science: students can learn science because they like

it (intrinsic motivation) and because they realize that

learning science is useful for their plans (extrinsic mo-

tivation), or both. In Brazil, between 2012 and 2015,

the percentage of students who had skipped a day of

school once or twice in the two weeks before the PISA

test increased by 21 percentage points, signaling a de-

terioration in students’ engagement with school dur-

ing the period.

The Vygotsky Activity Theory and Proximal De-

velopment Zone (ZPD) grounded the GSA. (Vygot-

sky, 1980). The first provides a language for un-

derstanding complex real-world activities located in

cultural and historical contexts, such as a classroom.

(Engestr

¨

om, 1987), (Hasan, 2013), (Leontjev, 1981).

As the latter examines the relationship between edu-

cation and development and is commonly associated

with the distance between the actual level of devel-

opment and the level of potential learning develop-

ment of individuals. In this context, we present the

GSA. The GSA implements Theory of Activity in-

volving people will be in activities and involving tech-

nological resources and creates learning opportunities

as promotes ZPD between teacher and pupils, since

these will count on the intervention of the teacher to

the point where they feel the need, obtaining infor-

mation necessary for the practical completion of the

content appropriation process.

This study addresses an initial assessment of GSA

acceptance with a group of teachers and students. The

GSA consists of a suite of applications (Android and

application server), and specialized communication

protocols for the classroom. To achieve this goal,

the GSA implements some strategies, such as promot-

ing student engagement in classroom activities and al-

lowing teachers and pedagogical coordinators to fol-

384

Damasceno, A., Ferreira, A. and Oliveira, F.

Understanding the Correlation between Teacher and Student Behavior in the Classroom and Its Consequent Academic Performance.

DOI: 10.5220/0007729103840391

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2019), pages 384-391

ISBN: 978-989-758-367-4

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

low up on students during these activities. Also, the

GSA provides a secondary communication channel

between teachers and students in a classroom. The

GSA automatically measures the level of comprehen-

sion of the class on the content presented. Another

strategy is the control of the use of the tablets of stu-

dents in the classroom by teachers.

The remainder of this article is organized as fol-

lows. Section 2 describes the problem with the

main elements relating cause and effect in the teach-

ing process in the classroom. Section 3 discusses

the main ideas for solving the problem. Section 4

presents GSA (with its characteristics and functional-

ities). Section 5 outlines the methodology adopted in

the evaluation. Section 6 presents and discusses the

results. Finally, Section 7 presents the conclusions

and identifies possible future work.

2 LOW LEVEL OF

ENGAGEMENT OF THE

STUDENT IN CLASSROOM

A significant challenge for Brazilian education in high

schools is to increase the engagement of students in

the classroom, to raise their school performance. This

work focused on investigating the possibility of ob-

taining an increase in the index of learning and a

decrease in school dropout using technological re-

sources, through the development of an application

to support teachers and students in the high schools

in Brazil’s Northeast (least developed region in the

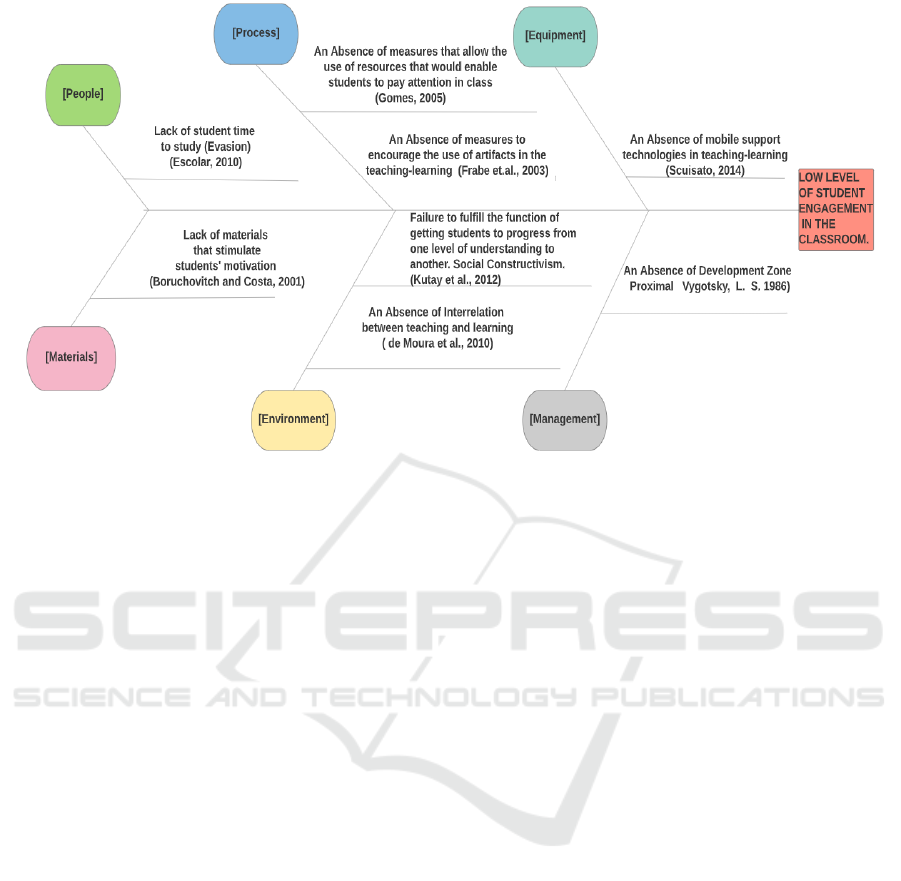

Country). Figure 1 illustrates the problem and its

leading causes.

2.1 Low Student Performance

According to Souza and de Souza (2013) Communi-

cation and Information Technologies (ICT) help the

studying and simplify the learning by making the

knowledge more structured. Technology facilitates

engagement in the relationship between teachers and

students in class. It is necessary to intervene on the

traditional method of teaching to improve the con-

struction of learning, characterized in a direct and

passive transmission of content and information from

teacher to students. GSA proposes the active partic-

ipation for students in school activities, through in-

teraction with colleagues and teachers, making use of

mediating artifacts, such as tablets and cell phones.

Based on this constructivist model (Castorina et al.,

2013), active learning is defined as a class style in

which students are involved, leading them to take

an active role in their learning process. The use of

tablets enables collaboration among students, which

also promotes learning. Active learning takes the stu-

dent from the traditional passive position and offers

more possibilities for engagement.

Several studies provide evidence of the positive

correlation between increased students engagement

and their increased school performance and their re-

tention of content in contrast to passive reception

(Smith et al., 2005), (Simoni, 2011). The use of

tablets in a classroom increases the level of student

engagement (Shishah et al., 2013). Student monitor-

ing allows teachers to address individual student de-

ficiencies and act upon them (Beyers et al., 2013).

Timid students risk learning less (Frambach et al.,

2014). It is necessary to create forms of participation

of shy students, without exposing them. The use of

devices that allow students’ responses to be automati-

cally corrected and the result displayed to the teacher,

give them the possibility to reinforce concepts that are

not yet wholly assimilated before proceeding (Her-

rmann et al., 2012).

According to Escolar (2017), soon the final years

of elementary school will overcome the last stage of

primary education concerning learning gains, due to

the current high school situation. The alert comes

from the results of the Basic Education Assessment

System (SAEB) 2017 and released by the Ministry

of Education (MEC) and the National Institute for

Educational Studies and Research An

´

ısio Teixeira

(INEP). The results show a high school that has been

almost stagnant since 2009, and with a weak contri-

bution to the cognitive development of Brazilian stu-

dents.

2.2 School Dropout

According to Neri et al. (2009), 4 in every ten brazil-

ian students who dropped out of school claimed disin-

terest as their primary reason for not attending classes.

According to the survey, these young people didn’t

see sense in the subjects taught and affirmed that the

contents didn’t stimulate them to the point of taking

the school seriously. Technologies can help motivate

teenagers and consequently reduce their school eva-

sion, as one solution to circumvent evasion is to adapt

teaching practices to the current generation of schools

by making use of technology as an ally in the class-

room. These young people grew with greater ease of

access to the Internet, with participation profile and

interaction in the more extensive networks. There-

fore, classes that are, in fact, great monologues, don’t

attract them. Proposing new teaching methods and

investing in technologies that supports the teaching-

Understanding the Correlation between Teacher and Student Behavior in the Classroom and Its Consequent Academic Performance

385

Figure 1: This figure was drawn up by the authors of this paper to illustrate the Diagram of the cause and effect of the low

level of student engagement in a classroom.

learning process can help reduce school evasion.

In Brazil, the history of the School Census reveals

a progressive decline in school dropout from 2007

to 2013 at all stages of schooling, but this pattern

changes in 2014 when rates increase. According to

Escolar (2017) between the years of 2014 and 2015

a percentage of 12.9% and 12.7% of the students en-

rolled in the first and second year of high school, re-

spectively, left school. The 9th year of elementary

education has the third highest evasion rate (7.7%),

followed by the third year of high school (6.8%). The

evasion is about 11.2% of total students considering

all high school.

Faced with the harsh reality in Brazilian educa-

tion and observing the main concepts that involve

the teaching-learning process, students and teachers

need technical support to overcome the problem con-

cerning the impact of low academic performance and

school dropout. Therefore, it opens up space for ap-

plications and fosters the production of educational

technologies, programs that are useful in the real

world.

In an article in his technology column in The New

York Times, (Richtel, 2010) argues that mobile tech-

nologies ”are in the DNA of new generations and that

any resistance to its use in the classroom is futile.”

The author also discusses concerns related to the dis-

traction brought about by the use of these devices in

the classroom. However, the adoption of such tools in

the classroom may not consider the issue of entertain-

ment an obstacle - the opportunities that arise from

its use are innumerable. Strategies and technologies

need to be created to provide the necessary security

and remove barriers to the entry of devices, such as

tablets, into the classroom. Such devices can be great

learning tools.

3 CREATING LEARNING

OPPORTUNITIES

Encouraging the student to use the recent learnt con-

cepts in a different context creates a vital learning op-

portunity. It is at this moment that gaps in knowledge

arise, the ZPD. The instructor’s attention at this par-

ticular moment is precious, providing the information

needed to validate the concept appropriation process.

Innovative ways to monitor how classroom activities

in the classroom - held - by teachers and pedagogues

to be necessary, the use of tablets facilitates this mon-

itoring.

According to followers of active learning theory

(Clancy et al., 2012), the student is the principal agent

of his learning. This theory can be easily evidenced

by observing the students conducting their research

for their school activities. Aware of their deficits, the

students seek to solve them, the Internet being the pri-

mary means used for this. In this context, the use of

tablets simplify such searches and enable collabora-

tion among students, which also contributes to learn-

ing. Active learning takes the student from the tra-

ditional passive position and offers more possibilities

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

386

for engagement. Studies show that the greater the en-

gagement, the higher the learning. With this, Internet

research should be stimulated, in the context of the

execution of the activities foreseen in the discipline.

It’s interesting to mention that these ideas are not so

recent. In 600 B.C., the Chinese philosopher Lao Tse

discussed the active learning theory: ”What I hear, I

forget. What I see, I remember. What I do, I under-

stand”.

New knowledge is, in many cases, acquired con-

structively. Like bricks on a wall, complex con-

cepts derive from more elemental ones. When a stu-

dent does not understand a specific idea, its base is

compromised, making it difficult to realize a more

complex concept derived from this more fundamen-

tal first. In traditional classrooms, teachers follow

their lessons assuming that all students are assimilat-

ing the ideas exposed unless someone manifests and

says otherwise. Cases in which students allow the

continuity of the class while maintaining a doubt for

themselves are frequent. Classrooms where students

respond through electronic devices, questions created

to investigate the understanding of the content deliv-

ered until a given point, provide teachers with instant

information about the degree of learning of the class.

Teachers can thus adjust the course of their classes to

enhance the learning level of all students, thus avoid-

ing the snowball effect of misunderstood contents.

The introduction of tablets in the classroom can

also provide the basis for the use of another essential

theoretical model, constructivism (Kutay et al., 2012).

The main idea of the theory is that we learn through

social interactions. At all moment we are learning and

teaching each other. When we engage in debates and

seek to convince others of our points of view, we use

the best of our arguments and all extension of knowl-

edge. Teachers aware of the power of constructivist

theory hold classroom discussions and group work.

Teachers can even allow students to control digital

whiteboards remotely through their tablets, favoring

scenarios of discussion and exposure of each student’s

opinions. The teacher herelf can manage and write

on the digital whiteboard from his tablet. Thus, she

can walk among the students as she writes on the

whiteboard, getting even closer to her class. Focusing

on the use of technology to bring together teachers

and students, students can ask questions directly and

confidentially to the teacher through chats. This new

open communication channel is of great value, espe-

cially for shy students, who benefit from secrecy to

accuse some point not completely understood of the

content exposed by the teacher.

One of the factors that hinder the adoption of these

techniques in the classroom is the time consumed in

their employment. ”Administrative” activities such as

benchmarking or copying content can be significantly

reduced by using technology in the classroom, cre-

ating employment opportunity for superior teaching

strategies.

The technology builds on the theories and strate-

gies outlined above. The GSA was made available to

the national and world market after having passed for

an experimental phase in real classrooms in a large

local school, presenting promising results.

4 CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT

APPLICATION (GSA)

The GSA was designed to mediate the relationships

between teachers and students while copresents in the

classroom through the use of tablets. The software,

of a simple application, can be used in the teaching of

any disciplines. The GSA, with the features described

below, is already available for commercial use. Its

functionalities have been specially developed to im-

prove the dynamics of the class with the use of digital

resources (electronic whiteboards, scanned contents

and tablets with Android technology).

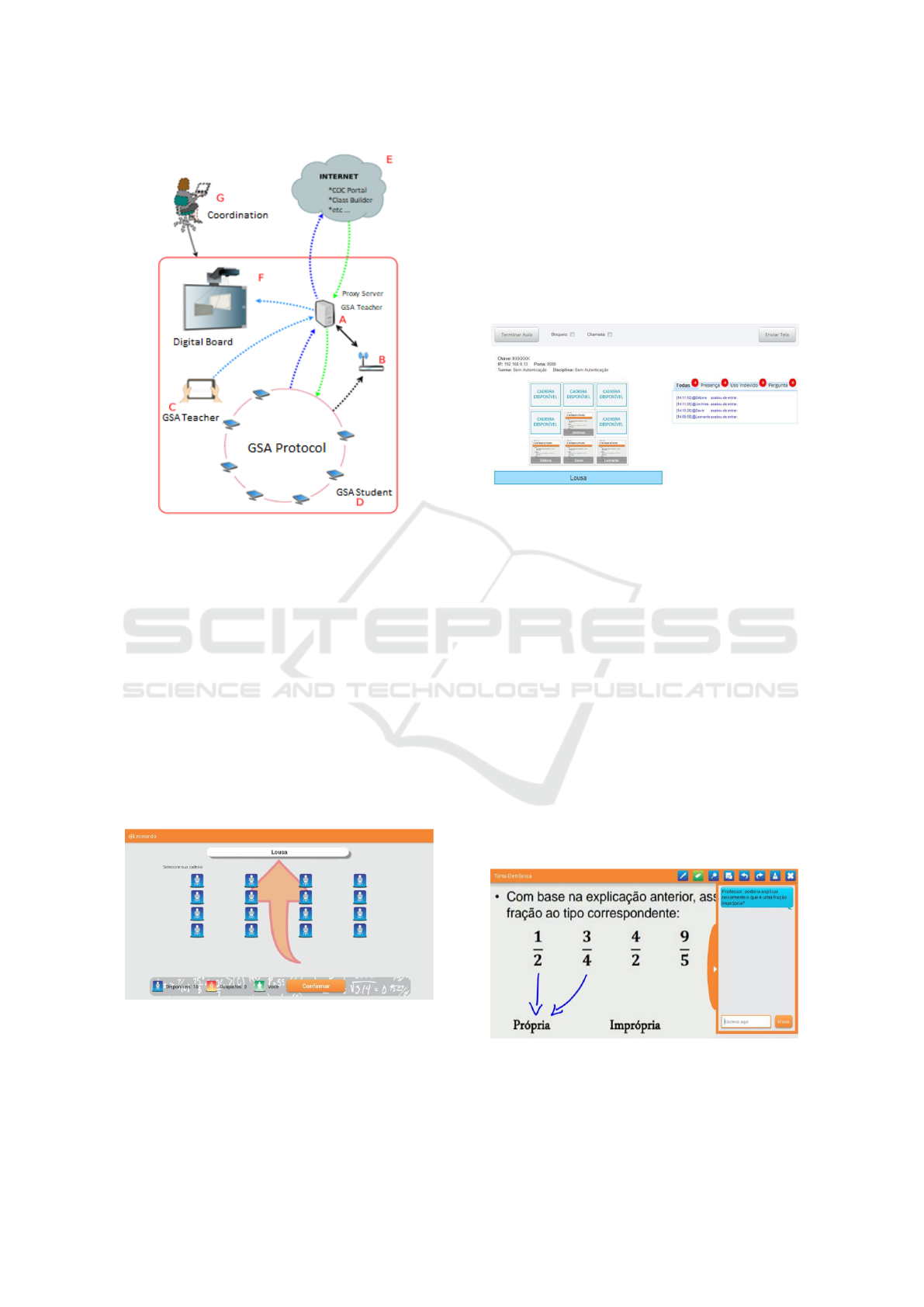

Figure 2 shows the description of the GSA opera-

tional protocol. The first graphic element that stands

out in the figure is the quadrilateral that delineates the

physical space of the room separating the intra-class

components from that extra-class of the solution. The

GSA communications protocol, implemented through

a series of computational services running on the root

server (indicated by the letter A in the figure), man-

ages all communications between the devices. The

tough loss of efficacy of high-density wireless net-

works in educational environments justifies the ex-

istence of a protocol so highly specialized, where it

was evidenced by (Florwick et al., 2011). In this ar-

ticle, the authors show in detail how the addition of

wireless devices (classrooms with more students) ex-

ponentially degrades the effectiveness of the network,

forming a challenging bottleneck to remove.

Aware of the problem, we have developed a spe-

cific communication protocol for the use of the GSA,

which proved useful in this type of environment. The

protocol, however, will require extensions to contem-

plate the requirements of this project. It’s impor-

tant to emphasize that the demand for computational

resources imposed by the protocol is relatively low

and it’s therefore feasible that these services reside

in the same equipment that controls the digital board

(F). Given the GSA protocol, you can use routers (B)

without many sophisticated features, which in addi-

tion to making the solution expensive can cause un-

Understanding the Correlation between Teacher and Student Behavior in the Classroom and Its Consequent Academic Performance

387

Figure 2: GSA Protocol.

desirable side effects such as shadowing. It is also the

protocol that will manage classroom communications

with Pearson products and any other remote services

(E). The solution is also composed of specific appli-

cations for teachers (C), students (D) and pedagogical

coordinators (G).

Between GSA resources, we highlight the Map of

the Classroom. When accessing the application, the

student informs in which chair he is sitting, touching

the image of a green chair on an electronic classroom

map (the red ones represent occupied chairs). The

teacher has access to this map from his tablet, which

allows him to meet all the students by name on the

first day of class. Figure 3 illustrates the room map.

Figure 3: Room map.

Another feature is the Electronic Call. At the be-

ginning of the class, the teacher authenticates himself

in the GSA, discloses the access key to the students

and activates the ”call” option. Automatically, as stu-

dents log in through their tablets, the GSA will record

the presence of all. Figure 4 shows on the map of

the electronic classroom an image of what appears on

each student’s tablet.

As soon as the lesson starts Monitoring happens

and if a student disables the GSA application on their

desk, the teacher will receive a notification informing

what happened. The GSA will then indicate which

student made the deactivation and where in the room

it is positioned.

Figure 4: Electronic call and monitoring.

One feature presented by the application is Con-

tent Sequencing, the teacher starts his presentation

on the electronic whiteboard and with the GSA he has

complete control over the sequencing of content pre-

sentation. It’s this functionality that manages the flow

of information and thus maintains the focus and at-

tention of students. At the beginning of the class, the

teacher projects his or her first slide on the electronic

whiteboard or multimedia projector, makes notes as

he moves through the class, and when he completes

the subject of the slide it passes to the students. Alter-

natively, he can design/share the slides as he projects

them, giving students the opportunity to take notes.

The Electronic Ink counts the pen, eraser, color

palette, thickness of risks, zooming and panning. It

serves as a kind of electronic notebook - the Elec-

tronic Ink is used in the resolutions of questions pro-

posed to the students. Figure 5 illustrates the Elec-

tronic Ink feature.

Figure 5: Electronic Ink.

The student can, through the Chat feature, dis-

creetly send questions and comments to the teacher’s

tablet. It’s a direct channel of communication be-

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

388

tween the shy student and the teacher.

Together with the Electronic Ink feature, the Au-

tocorrect will give the teacher the possibility to au-

tomatically measure the degree of comprehension of

the students in the course of the class, allowing him

the adjustment of the exposed and the reinforcement

of certain concepts. Figure 6 illustrates the ”Autocor-

rect” functionality.

Figure 6: Example of auto-broker. Student emphasizes the

word (black griffin) and the GSA automatically answers the

answer (green griffin).

With the GSA we seek to solve the problem of the

low level of engagement of the students in the class-

room, impacting on their improvement of school per-

formance and reduction of evasion from the imple-

mentation of strategies listed and discussed below:

1. Promote Engagement of Students in Class-

room Activities. Several studies provide ev-

idence of the positive correlation between in-

creased student engagement and improvement in

content learning and retention, in contrast to pas-

sive reception (Smith et al., 2005) (Hrepic, 2009)

(Simoni, 2011). The use of tablets in the class-

room increases the level of student engagement

(Shishah et al., 2013).

2. Allow the Monitoring of Students, by Teach-

ers and Pedagogical Coordinators, While Car-

rying out these Activities. Student monitor-

ing allows teachers to address individual student

deficits and act upon them (Beyers et al., 2013).

3. Create Secondary Communication Channels

between Teacher and Students allowing Class-

room Use. Shy students risk learning less (Fram-

bach et al., 2014). It’s necessary to create ways

to encourage shy students to participate more ac-

tively during the classes, but without exposing

them.

4. Automatically Measure the Level of Compre-

hension of the Class about the Concepts un-

der Discussion. The use of devices that allow

students’ responses to be automatically corrected

and the result displayed to the teacher, give them

the possibility to reinforce concepts that are not

yet wholly assimilated before proceeding with the

content (Herrmann et al., 2012).

5. Allow the Control of the use of the Students’

Tablets in the Classroom by Teachers. The

GSA experience in the classroom shows that this

functionality is never activated because students

are engaged in the tasks assigned to them by

teachers. However, functionality must be main-

tained, increasing the level of confidence of teach-

ers as it demonstrates to students their authority

and even strengthens in this new scenario.

The technology uses Activity Theory through the

tasks generated between teachers and students as co-

chairs in the classroom with exposure to the applica-

tion. According to (Carroll, 2003), the Activity The-

ory allows us to study several levels of activity com-

bined: from the activity of strict use of a computa-

tional artifact to the broader context of use and design.

It also allows you to modify the scale and study the

connections at multiple levels of activities in which

computational artifacts are used and designed, with-

out establishing a permanent hierarchy in the analy-

sis.

5 METHODOLOGY

In this section, we will present the GSA assessment

methodology. In this evaluation was applied an

experiment to evaluate the impact that the technology

that makes use of the theory of active learning causes

in the engagement of students in the classroom.

Besides, we assess the GSA for validation of its

operation.

Application of the Comparative Questionnaire

to the End of the Experiment

A post-experiment questionnaire was applied, at

the end of the class using the technology. At the time

the activity was completed, the participant answered

the survey, to guarantee the fidelity of the answers

concerning their involvement in the experiment and

with the final objective of ascertaining the acceptance

of the user when using the tool.

At the end of the experiment, the research subjects

answered the questions, with which it was possible

to compare the traditional class with the class using

the supporting technology and observe how the tool

used was analyzed. The issues were elaborated us-

ing a five-point Likert scale, responses ranging from

”strongly disagree” to ”strongly agree.”

With the application of this questionnaire we tried

to answer the following questions: Are students more

Understanding the Correlation between Teacher and Student Behavior in the Classroom and Its Consequent Academic Performance

389

motivated to participate in another lesson with the

tool? Teachers and students would like to rely on

this technology in future classes? The device does

not disturb the communication between teachers and

students? We observe the correlation of classroom be-

haviors between teachers and students as to the activ-

ities in which they are involved.

6 DATA ANALYSIS

A large school has closely followed the evolution of

the GSA project. Its conservative stance is justified

since there is a long history in the city of schools that

tried to use tablets in their classrooms and failed. The

school has allowed access to its facilities, students and

teachers, on an experimental character.

With the GSA we taught classes in Mathematics,

Geography, Chemistry, Biology, Portuguese and En-

glish. At the end of their first class with the GSA,

the students answered electronic questionnaires using

the tablets they were using (Likert scale assertions).

Figures 7 and 8 illustrates the results for students and

teachers.

Figure 7: Students result.

Figure 8: Teachers result.

6.1 Discussion

We tested a trial version of the GSA with 123 high

school students and 15 teachers, all members of the

institution mentioned above. Teachers and students

were introduced to the GSA minutes before classes

began. With the training reduced to minutes, the

seamless use of the GSA functionality strongly indi-

cates the adoption of large-scale the GSA in Brazilian

high schools. However, the logistics of training hun-

dreds of teachers and students add undesirable costs

to product adherence and constitutes a barrier to entry

of the product into the market.

The GSA worked perfectly. The teacher and stu-

dent community approved the GSA. Front a positive

evaluation, the college itself acquired some licenses

from the GSA, instructed its IT staff to pursue further

testing and renewed its commitment to continue vali-

dating new versions of the GSA on its premises.

7 CONCLUSIONS

This paper deals with the psychological correlatives

of school performance related to the attitudes of stu-

dents and teachers of the high school in the classroom

captured automatically through the GSA application.

As a contribution of this study, the GSA im-

plementation allows monitoring frequency, engage-

ment in classroom activities and accuracy percentages

among corrected questions by the autocorrect func-

tionality. Besides that, the GSA shows the rate of

neighbors’ correct answers (given the GSA electronic

classroom map functionality), number of notes made

in the electronic notebooks and the number of ques-

tions asked to the teacher (through the chat function).

All these indicators are examples of potential predic-

tors.

As future work, we intend from the tools already

available and in a project to address some interesting

scenarios. Among them, we highlight the possibility

of predicting students’ school performance. The pro-

posed innovation is the construction of a set of perfor-

mance predictors, from the data collection with the

use of the GSA in the classroom. You will not have to

wait for the end of semester tests to know that students

who do not participate in classroom activities or who

do not respond correctly to questions (corrected auto-

matically) will perform poorly. The pedagogical team

of the educational institution together with parents

may use performance predictors, to rescue early stu-

dents with difficulty. The frequency, engagement in

classroom activities, percentages of correct answers

(among the questions corrected by the autocorrect),

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

390

the rate of correct answers of neighboring students

(given the GSA electronic classroom map function-

ality), the number of notes made (the role to be de-

veloped in the GSA to record these events) are ex-

amples of potential predictors. The challenge here is

pedagogical. How will students and educators react to

the availability of such predictors? What impacts will

these numbers have on educational practices? How

will the parents and guardians be notified and what

will be their reaction? We foresee strong changes

in the relationships between the teaching/learning ac-

tors. Thus, given the depth of impact, the approach

requires some scientific rigor in proposing and evalu-

ating changes in experimental setup.

REFERENCES

Beyers, S. J., Lembke, E. S., and Curs, B. (2013). Social

studies progress monitoring and intervention for mid-

dle school students. Assessment for Effective Interven-

tion, 38(4):224–235.

Boruchovitch, E. and Costa, E. d. (2001). O impacto da

ansiedade no rendimento escolar e na motivac¸

˜

ao de

alunos. A motivac¸

˜

ao do aluno. Contribuic¸

˜

oes da psi-

cologia contempor

ˆ

anea, pages 134–147.

Carroll, J. M. (2003). HCI models, theories, and frame-

works: Toward a multidisciplinary science. Elsevier.

Castorina, J. A., Ferreiro, E., Lerner, D., and de Oliveira,

M. K. (2013). Piaget vygotsky: novas contribuic¸

˜

oes

para debate. Cadernos de Pesquisa, (96):83.

Censo, E. (2010). Br. organizac¸

˜

ao associac¸

˜

ao brasileira de

educac¸

˜

ao a dist

ˆ

ancia. S

˜

ao Paulo: PearsonEducation

do Brasil.

Clancy, S., Bayer, S., and Kozierok, R. (2012). Active

learning with a human in the loop. Technical report,

MITRE CORP BEDFORD MA.

de Moura, M. O., Ara

´

ujo, E. S., Moretti, V. D., Panossian,

M. L., and Ribeiro, F. D. (2010). Atividade orienta-

dora de ensino: unidade entre ensino e aprendizagem.

Revista Di

´

alogo Educacional, 10(29):205–229.

de Souza, I. M. A. and de Souza, L. V. A. (2013). O uso

da tecnologia como facilitadora da aprendizagem do

aluno na escola. Revista F

´

orum Identidades.

Engestr

¨

om, Y. (1987). Learning by expanding: An activity-

theoretical approach to developmental research.

Escolar, C. (2017). Dispon

´

ıvel em:¡ censobasico. inep. gov.

br¿. Acesso em, 2.

Fabre, M.-C. J., Tamusiunas, F., and Tarouco, L. M. R.

(2003). Reusabilidade de objetos educacionais.

RENOTE, 1(1).

Florwick, J., Whiteaker, J., Cuellar, A., and Woodhams, J.

(2011). Wireless lan design guide for high density

client environments in higher education-cisco guide,

san jos

´

e.

for Economic Co-operation, O. and (OECD), D. (2016).

Pisa 2015 results in focus.

Frambach, J. M., Driessen, E. W., Beh, P., and van der

Vleuten, C. P. (2014). Quiet or questioning? stu-

dents’ discussion behaviors in student-centered edu-

cation across cultures. Studies in Higher Education,

39(6):1001–1021.

Gomes, E. R. (2005). Objetos inteligentes de aprendizagem:

uma abordagem baseada em agentes para objetos de

aprendizagem.

Hasan, H. (2013). Being practical with theory: a window

into business research.

Herrmann, A., Reinicke, B., Vetter, R., Clark, U., and

Grove, N. (2012). urespond: A classroom response

system on the ipad. Annals of the Master of Science in

Computer Science and Information Systems at UNC

Wilmington, 6(1).

Hrepic, Z. (2009). Impact of tablet pcs and dyknow soft-

ware on learning gains in inquiry-learning oriented

courses.

Kutay, C., Howard-Wagner, D., Riley, L., and Mooney,

J. (2012). Teaching culture as social constructivism.

In International Conference on Web-Based Learning,

pages 61–68. Springer.

Leontjev, A. N. (1981). Problems of the development of the

mind.

Neri, M. C., Melo, L., Monte, S. d. R. S., Neri,

A. L., Pontes, C., Andari, A. B. U., et al. (2009).

Tempo de perman

ˆ

encia na escola. Rio de Janeiro:

FGV/IBRE/CPS.

Richtel, M. (2010). Growing up digital, wired for distrac-

tion. The New York Times, 21:1–11.

Shishah, W., Hopkins, G., FitzGerald, E., and Higgins, C.

(2013). Supporting interaction in learning activities

using mobile devices in higher education. QScience

Proceedings, (12th World Conference on Mobile and

Contextual Learning [mLearn 2013):35.

Simoni, M. (2011). Using tablet pcs and interactive soft-

ware in ic design courses to improve learning. IEEE

transactions on Education, 54(2):216–221.

Smith, K. A., Sheppard, S. D., Johnson, D. W., and Johnson,

R. T. (2005). Pedagogies of engagement: Classroom-

based practices. Journal of engineering education,

94(1):87–101.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1980). Mind in society: The development

of higher psychological processes. Harvard university

press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1986). Thought and language (rev. ed.).

Understanding the Correlation between Teacher and Student Behavior in the Classroom and Its Consequent Academic Performance

391