Start@unito: Open Online Courses for Improving Access and for

Enhancing Success in Higher Education

Marina Marchisio

1 a

, Lorenza Operti

2 b

, Sergio Rabellino

3 c

and Matteo Sacchet

1 d

1

Department of Mathematics “G. Peano”, University of Turin, Via Carlo Alberto 10, Torino, Italy

2

Department of Chemistry, University of Turin, Via P. Giuria, 7, Torino, Italy

3

Department of Computer Science, University of Turin, Via Pessinetto 12, Torino, Italy

Keywords: Digital Education, e-Learning, Higher Education, Open Online Courses, University Guidance.

Abstract: Digital Education, in particular open online courses, plays an important role in providing free education to

people who wants to learn. The University of Turin, with the financial support of the bank foundation

Compagnia di San Paolo, has developed the project “start@unito”: a selection of university modules in a

broad range of topics, administered through open online courses freely available. These courses could be also

used to facilitate the transition between secondary and tertiary education and to enhance the success in Higher

Education. In this paper we discuss the project, focusing on the adaptive solutions adopted in the preparation

of the online resources and describing some results after the first nine months of courses availability.

1 INTRODUCTION

Since the beginning of the third millennium, the use

of technology for learning purposes has increased

quantitatively and qualitatively together with the

improvement of technology itself.

Across the years, many attempts to create

effective e-learning programs took place and

interacted with the development of tools and

protocols, like free copyright licenses Creative

Commons, the construction of repository programs

and MOOCs and the birth of virtual communities of

practice.

The digital education, which uses the information

technologies to support learning, can be a useful tool

for the realization of the declaration of Rights to

education primers (Tomaševski, 2001), which

elucidates key factors, like the respect of all human

rights in education, as well as enhancing human rights

through education. This document, which directly

follows from the Universal Declaration of Human

Rights, stated the most important features that

education must have through 4 “A”:

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1135-4739

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1007-5404

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1757-2000

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5630-0796

acceptability, to ensure that education is of good

quality, thus enforcing the mininal standards;

accessibility at different levels: access to

education must be secured and free for all children

at least in the compulsory education age-range

(elimination of barriers and ostacles like distance,

fees, gender discrimination);

adaptability, which states that schools ought to

adapt to children, according to the best interests of

each child and paying attention to people with

disabilities;

availability, which means allowing the

establishment, funding and using of educational

institutions by non-state actors.

Nowadays the trend is to focus mainly on open

digital education. The main reason of this choice

resides in the diffuse access to the world wide web via

many kind of devices from anywhere. In this context,

many institutions, mainly universities. devoted to

spreading education, are trying their best in order to

prepare Open Educational Resources (OER). In fact,

universities must accomplish their Third Mission,

that is to generate knowledge outside academic

environments to the benefit of the social, cultural and

Marchisio, M., Operti, L., Rabellino, S. and Sacchet, M.

Start@unito: Open Online Courses for Improving Access and for Enhancing Success in Higher Education.

DOI: 10.5220/0007732006390646

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2019), pages 639-646

ISBN: 978-989-758-367-4

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

639

economic development. At the University of Turin,

thanks to a funding from the bank foundation

Compagnia di San Paolo, the project “start@unito”

was born: a collection of open online courses which

are complete university modules, available to anyone

and anytime. The courses were built by experts in

each subject, university professors and grant holders,

who were also trained in the latest digital education

technologies and methodologies (Bruschi et al., 2018)

Unlike the repositories of open educational

resources like MERLOT (https://www.merlot.org),

OER Commons, etc. available online, start@unito

aims at providing open learning, which includes both

content and didactic support to learning, primarily in

the form of adaptive assessment and personalized

feedback. By design the program does not avail itself

of online tutors, forums or teacher-student

interaction. Therefore, the biggest challenge is to

create interactive contents that somehow compensate

the missing learning interaction.

2 STATE OF THE ART

E-learning provides many advantages (Ross et al.,

2010): it offers a variety of freely available contents;

it is a more affordable training opportunity for

students because all they need is a device connected

to the web; it can accommodate everyone’s needs; it

provides adaptive learning. Apart from these

numerous advantages, it is important to recall that

Technology Enhanced Learning (TEL) is not

effective by itself, but it needs knowledge and deep

understanding on how technology works (Hicks

2011). In fact, the quality of the digital learning

materials is very important, especially according to

the following tasks: enhancing learning (Sangwin

2015); supporting metacognitive processes (Nicol

and Macfarlane-Dick, 2006); facilitating adaptive

teaching strategies (Barana et al., 2017c). The

University of Turin has an historical background in e-

learning since the beginning of the new century.

Nowadays in Italy, the University of Turin is quite

advanced in the use of digital technologies, both in a

local setting with the projects “Scuola dei compiti”

(Barana et al., 2017c) and “Orient@mente” (Barana

et al., 2017a; Barana et al., 2017b), at a national level

with the projects “PP&S Problem Posing and

Solving” (Brancaccio et al., 2015b) and in a European

context with the project “SMART Science and

Mathematics Advanced Research for good Teaching”

(Brancaccio et al., 2015a). In the Italian scenario,

there are two other important platforms that deliver

online courses: EduOpen (Rui, 2016) and Federica

(Calise and Reda, 2017). EduOpen, designed by

University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, enlists 17

Italian universities as members and hosts 150 online

courses about basic and professional disciplines and

professional scientific research. Federica platform,

developed and maintained by the University of

Napoli, refers to the study materials of about 100

university modules in e-Learning, available at any

time, with contents organized in training modules. In

a worldwide view, there are many providers of

Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), like EdX

(https://www.edx.org/) and Coursera

(https://www.coursera.org/), which launched the

concept of MOOC itself and are, even today, used by

a huge number of learners. These open platforms

issue electronic course certificates after attending a

course within a strict period (course edition) and

together with other learners (virtual classes). Many

universities in Northern Europe and North America

have joined these platforms to make their online

courses available as a sort of university showcase.

Users of the MOOCs of these platforms are usually a

very large number, but only a small percentage of

them complete the MOOCs and get certified.

Although one-third of MOOC participants are from

North America, MOOCs have a global reach – with

regional distinctions: for example, Africans enroll at

twice the rate in social science courses than other

courses. South Asians are most likely to take

engineering and computer science courses

(http://monitor.icef.com/2014/07/who-uses-moocs-

and-how/).

Working all at the same time is one of the

advantages of supplying online contents of this kind,

giving stimuli to reach the top in the ranking of the

course; on the other hand, users are usually forced to

complete activities to view the next parts.

3 THE START@UNITO PROJECT

3.1 Description

With the project “start@unito”, the University of

Turin provides learners with a Learning Management

System (LMS), available at https://start.unito.it, that

delivers, at the time of writing, twenty freely

available, self-paced, online courses on different

topics. Anyone can follow these free online courses

even if not enrolled at the university. These courses

cover many first year disciplines from four different

areas (scientific, humanistic, economic, law).

Registering to the platform is quick and easy using

social network credentials. There are no time

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

640

restrictions, thus the pace of study is autonomous,

there are many practice self-assessment tests and

many multimedia contents to explore. After

completing all the proposed activities of a course and

passing the final test, students receive a certificate of

attendance of the online course and they can take the

university exam as soon as they enroll in a degree

course.

3.2 Objectives

The main goal of the project, already reached in other

projects (Barana et al., 2017a; Barana et al., 2016a;

Barana et al., 2017b), is to facilitate the transition

between secondary and tertiary education and to

enhance the success in Higher Education: usually

there is a big difference between learning in high

school and at the university. Making the students

anticipate their career by taking a complete exam

prior to their enrolment at the university could

improve the outcomes of first year university

students. This is important for the evaluation of the

education quality provided by the institution: these

criteria are tied to the number of ECTS credits

acquired during the first year of university studies and

to the drop-out rate calculation. Moreover, by

involving many people from different departments

with the preparation of online courses, the University

of Turin aims to spread the use of digital technologies

in university activities. Finally, an online course

could be useful for students in many other ways: as a

means of orientation, in order to understand if the

topic is of interest for the students and improve

university guidance. In addition, students are

supported at the start of their university education

path and provided with an overview of the education

programs offered by the university.

3.3 Target

The courses are aimed primarily at high school

students who wish to choose a university career

before enrolling or to sit an exam even before the start

of the academic year, but they are also open to off-

site or foreign university students. Moreover, access

to self-paced courses may be beneficial for both

disabled and particularly gifted students. The

problems that University of Turin wants to address

with this project are of different kind:

different approach to the subject between

secondary school and university;

students face mandatory exams for which they

have no aptitude, and usually are not easy to pass;

the lecture rooms are full of students, making it

hard to attend;

low self-awareness of students’ responsibilities

and duties regarding their study;

many students change course of study after the

enrollment;

difficult access to some of the bachelor courses

due to admission tests;

scarce use of e-learning in university modules;

working students and students with special needs

have difficulties in attending lectures.

3.4 Model

In order to prepare the online courses, people

involved in start@unito used their best knowledge

about didactics and technology. In fact, it is

universally acknowledged that technology itself is not

enough for extracting the best from the learning

process. The actors involved in the project adopted a

model for the preparation of the open online courses

inspired by the Deming Cycle: Plan, Do, Check, Act.

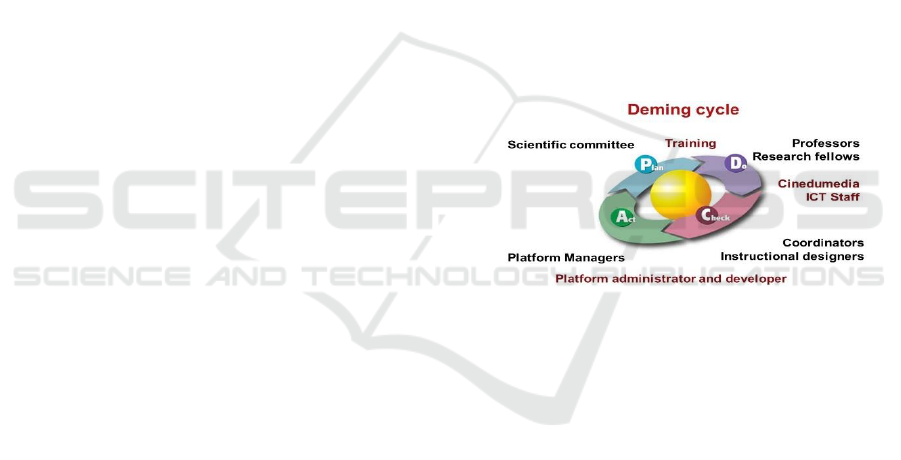

Figure 1: The Deming Cycle.

Plan: the Scientific Committee, who is in charge

of planning the project, is composed of Professors

who have already an intense experience in online

learning. The Chief of the Scientific Committee is the

Vice-Rector, supported by the project manager,

expert in digital education, and by two Research

Fellows and Coordinators, who were expert and

became more expert about e-learning and

surroundings.

Do: a group of experts in their own teaching

subject is engaged in creating the courses, helped by

coordinators, by Junior Grant Holders and with the

guidance of professors of the Department of

Philosophy and Educational Sciences, of the staff of

the IT and E-learning bureau (DSIPE) and of an

interdepartmental center, Cinedumedia

(http://www.cinedumedia.it/) devoted to multimedia

production. In order to facilitate their work,

professors and fellows attended a training session in

which they rethought the contents in terms of learning

objects, they gained confidence with the platform and

Start@unito: Open Online Courses for Improving Access and for Enhancing Success in Higher Education

641

with many other tools for preparing digital contents,

they learned the basics about copyright, accessibility

and web language.

Check: coordinators, acting as Instructional

Designers, validate the contents, manage platform

and communication, dispose online support and

elaborate data.

Act: platform managers, in agreement with

researchers, provide adjustments according to

feedback from students.

Behind the scenes, a useful help was provided by

the technical platform manager, experienced in

handling and developing the virtual learning

environment Moodle.

3.5 Tools

The University of Turin manages its e-learning

platform and hosts school teachers and students for

educational projects (Giraudo et al., 2014; Barana et

al., 2016b; Marchisio et al., 2017). Based on the

previous experience of University of Turin, the

project adopted a Learning Management System

(LMS) Moodle (https://moodle.org/), which provides

a single, robust, pluggable, customized and secure

system. Pluggability is the main feature, because the

platform is integrated with many tools. The main

integration, which has been partly developed and

maintained by the University of Turin since 2008, is

the one with the Maple suite. The Maple suite is a

powerful Advanced Computing Environment (ACE)

which consists in two main online tools mainly for

STEM oriented disciplines (Science, Technology,

Engineering and Mathematics) useful to analyze,

explore, visualize, and solve mathematical problems:

Maple NET and Maple T.A. The first one is devoted

to turn native Maple Worksheet into online resources

(Baldoni et al., 2011), the second one is an Automatic

Assessment System (AAS) that, beyond the natural

use of testing and monitoring students results with

freely available homework, allows a large flexibility

inheriting many benefits from the computing

environment, especially geometric visualizations in

two and three dimensions, interactive components,

algorithms, randomly generated variables. The Maple

T.A. integration (recently turned into Moebius

Assessment, https://www.digitaled.com/) allows

assignments to be run as Moodle resources with an

automatically updated results gradebook (Barana et

al., 2015, Barana et al., 2016).

The integrated tool for hosting videos is Kaltura

(https://www.kaltura.com/), a Software as a Service

(SaaS) solution which allows great flexibility and

many powerful properties, like quizzes inserted

directly in videos in order to make students’ learning

more effective.

3.6 Structure of the Modules and

Learning Objects

The courses structure is modular and displayed

through a grid format, according to the general

guidelines for the creation of e-learning course

(Rogerson-Revell 2007); each section, which is worth

one ECTS, corresponding to a different topic, for the

purpose of addressing students through the course

contents and of showing the whole content at a

glance.

When accessing the online course, students can

choose their own path among the topics and materials,

following their interests. All the activities do not flow

automatically in front of students’ eyes: they must

explore each one and browse pages and questions.

The first contents of each course are an introduction

to the course, the learning outcomes, and some useful

information about how to have the course recognized

by the University of Turin, along with some

information on exam procedures and how to correctly

explore the online course itself.

Within the course the other resources are

organized through the structure of a learning object.

Entry test and introduction: before going through

the online contents, a test is useful to see if students

have the right prerequisites and make them aware on

what they are going to learn in the following steps;

Online contents: short resources in which just one

concept is introduced briefly. Sometimes resources

are integrated with quick tests;

Summary: map of all the concepts studied, with

hyperlinks to the referred resource;

Exit self-assessment test: to allow the students to

check their learning.

Deepening (External resources): the web provides

a huge quantity of videos, journals, articles, blogs,

scientific sites, official pages, data, which could be

useful for the student to have a look at. They are

inserted according to their copyright regulations.

Other course tools available are:

Glossary: a list of the most important words and

concepts of the course, with hyperlinks to definitions

directly within the texts of online resources. This way

lessons are highly interactive;

Progress bar: the relevant course resources allow

completion tracking, providing the student with an

overview of their study, what resources are already

studied and what is missing;

Gradebook: at any time, students can check their

grades and their test details.

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

642

3.7 Adaptive Methodologies

Since students are alone in the learning process, many

adaptive methodologies were adopted during the

preparation of the open online courses.

First, modules contain many tests with automatic

assessment and activities of interactive exploring

which allow the students to self-verify their

comprehension. It is well known that assessment and

metacognition are deeply interlaced: frequent and

well-structured feedback helps learners understand

where they are going and how they are going, giving

information not only about how the task has been

performed (task level), but also about the process that

should have been mastered (process level), and

enabling self-regulation and self-monitoring of

actions (self-regulation level) (Hattie at al. 2007). In

case of difficulties or important conceptual nodes,

particularly in STEM disciplines (Science,

Technology, Engineering, Mathematics), or in case of

wrong answer to a question, adaptive questions were

inserted through Moebius Assessment, which step-by

step guide the student to the resolution and

interactively show a possible process for solving the

task. The step-by-step approach to problem solving

with automatic assessment is conceptualized in terms

of feedback, highlighting the formative function that

the sub-questions fulfil for a student who failed the

main task. The interactive nature of this feedback and

its immediacy prevent students from not processing

it, a well-known risk that causes formative feedback

to lose all its powerful effects (Sadler 1989).

Moreover, students are rewarded with partial grading,

which improves their motivation.

Questions are always available, automatically

changing the embedded data, helping the students to

repeat the reasoning without learning by heart. The

use of this automatic formative assessment raises the

awareness of the students and let them know their

progress in real time. This adaptive learning strategy

was deeply studied and experimented with excellent

results (Barana et al., 2018; Barana et al., in press).

Moreover, many other strategies were adopted in

order to facilitate the autonomous study:

the videos inserted in the open online courses are

short to let the student focus;

the conceptual maps help the student to move and

to find the topics easily inside the module;

the animations and the variety of learning objects

inserted make the study workload lighter;

the possibility to print the material allow students

to read the lessons offline.

3.8 Properties of the Model

The model is characterized by the following

properties.

Availability: materials are distributed under a

Creative Commons license; they can be freely re-used

in schools or in other learning contexts.

Accessibility: the LMS uses the high-legibility

font “EasyReading” (http://www.easyreading.it/)

which was designed for people with dyslexia, but

proved to be useful for everyone; all resources were

designed taking into consideration many accessibility

details like color contrast, short sentences,

transcriptions of videos, etc.

Adaptability: the structure is versatile to suit

different learning approaches and teachers’

requirements.

Consistency: many projects within the

University of Turin adopted the model, thus

improving students’ familiarity with the system

throughout their career.

Control: coordinators perform analysis and, if

necessary and in agreement with professors,

corrections; immediate and interactive feedback

provides a useful support to students.

Convenience: the system is suitable for research

or exploiting new technologies.

Efficiency: the model is one of the first points of

contact between learners and institutions.

High Quality: the online contents are created by

qualified personnel, through the collaboration of

experts from distinct ranges of expertize.

Sustainability: contained costs for students, they

are only asked to maintain a device and its connection

on their own.

Usefulness: there are many ways in which this

project is useful: to students, because they are more

aware of their enrollment choices, positively affecting

institutions and improving the quality of courses; to

professors, who acquire new skills and can use all the

start@unito materials during their lectures.

3.9 Certification

At the end of an online course, a certificate of

acquired knowledge is issued, certifying the

attendance to the module and the passing of the final

automatic assessment tests. This certification is

required to attend the university examination and thus

to obtain the ECTS. At the beginning of the current

Academic year, one hundred students enrolled at

University of Turin and took the university

examinations in order to obtain the ECTS.

Start@unito: Open Online Courses for Improving Access and for Enhancing Success in Higher Education

643

4 RESULTS

The project started in July 2017 with 20 university

modules prepared for the academic year 2018/2019.

The platform currently counts around 7000

(November 2018), which are rapidly increasing in the

latest months. In February 2019, more than 5000

students added these modules to their career plan.

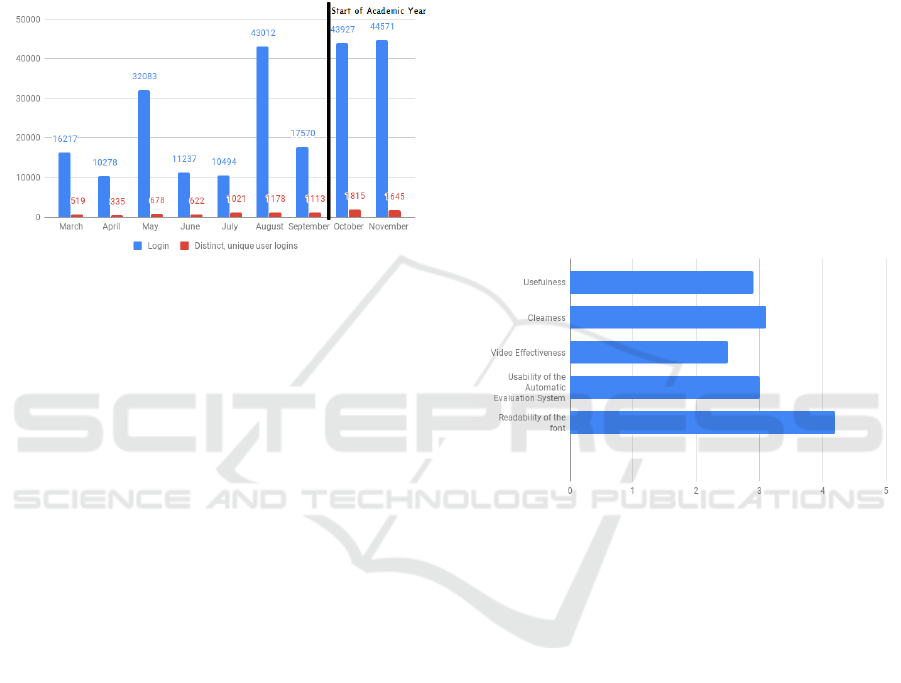

Figure 2: Number of Logins and Unique logins in 2018.

Looking at the users’ login to the platform in

Figure 2, it appears that before and after the high school

final exam, respectively in May and August, there is an

increased number of accesses. July and August is a

good period for online learning, as the high school

students are preparing for their university career,

because they just ended the 5-year-cycle and they are

evaluating which path will be the right one for their

future. After September, exams and usual university

activities start bringing to an increase in the number of

logins to the platform: from March 2018 to February

2019 students completed more than 160000 activities.

The number of subscriptions to courses is subject

to several factors: mostly the attitude of students,

which is unpredictable, but also an attractive title, the

advertisement or the presentations made in schools can

help in shaping the choices. Students can interact with

the course in many ways: a number of students just had

a quick look at the courses, in fact the percentage of

students who completed less than 30% in a single

course hovers around 90%, while a small percentage of

students, around 5%, completed the course they

started. In this setting, the course was considered

completed when more than 60% of activities were

marked complete, because in some activities the

completion marking is not automatic, but the mark it’s

a users’ choice (i.e. some assessments are not marked

automatically because there are no constraints related

to the tests and users can mark it complete when they

feel satisfied about their results). According to

researches (Jordan 2015), the completion rate of an

online course has a mean value around 12%. Further

analyzing the completion progress of students, it must

be noticed that some users, around 5%, who did not

complete the course, moved directly to a specific topic.

This behavior is highlighted by a set of sequentially

completed activities. Other students probably used the

course for a revision (around 10%): this could be

noticed by the fact that more than one activity is

skipped and the progress bar is clearly fragmented.

Simply skipping one activity is not enough to say that

a student used the course for a revision. All these

behaviors reflect the open access nature of the

platform, combined with the absence of time

constraints. After the completion of the course,

students are asked to fill in a questionnaire. It is

important to mention that there is no online tutoring:

professors support only the regular university students.

Figure 3 below summarizes the mean of the answers

we have obtained so far.

Figure 3: Results from final evaluation questionnaire (1 =

Very poor, 5 = Very good).

Analyzing the data, we can see how the

appreciation of video resources is slightly below

average. Students declared to prefer textual resources

like web pages, lessons, books (74%) compared to

video resources (22%). This may also depend on the

device used for viewing online resources: users with

mobile devices prefer videos. In fact, 67% of the

students used a personal computer, while 16% used

the smartphone and 16% used a tablet.

Students can write global feedback on the course.

Here there are some examples: “The course as a

whole is clear, well organized and well explained”,

“The list of topics to be studied allows a general

understanding of what to study from a textbook”,

“Good way to anticipate an exam”, “It allows not to

attend lessons”, “It allows a free management of

study and learning time, and provides a complete

overview of the exam topics”, “It is exciting to

follow, it feels like being in the classroom”. These

answers from students represent important feedback,

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

644

which might suggest improvements for both the

existing and the new courses.

Some difficulties were met during the preparation

of the open online courses. For example, the training of

the grant holders and teachers took more time than we

thought because only few of them were already used to

thinking about digital materials or to using the Moodle

platform for their lessons. It was very important to

support them constantly and to have regular meetings

with them in order to find together the best solutions

for the different needs of each subject. Moreover, the

advertising of the Project started a bit late. Many high

school teachers complained about the fact that for them

it was important to have the open online courses

available already from the beginning of the year

because they could have used them with their students

to deepen some topics.

5 FUTURE

The internationalization of university modules is a

key point for the future of the project start@unito.

The University of Turin will extend the offer of the

project adding 30 new open online courses for the

academic year 2019-2020, including some missing

disciplines, like Pedagogy, Chemistry, and a set of

courses in foreign languages specifically designed for

students included in exchange and mobility programs.

Many of the new courses are being developed in

English: this has the precise purpose of promoting the

internationalization and the mobility of students.

A further development of the start@unito project

concerns the achievement of the objectives through

the use of measurable parameters regarding the

number of ECTS achieved by the students in the first

academic year 2018/2019 and the drop-out rate.

Furthermore, a control of the contents and

materials online is foreseen according to the feedback

obtained from the students and a survey will be

submitted to professors to evaluate their experience in

designing and preparing online contents and adopting

a common examination procedure.

6 CONCLUSIONS

Start@unito comes from a previous and thorough

experience of the University of Turin about digital

education. Through meetings with secondary school

teachers and with students, the use of online resources

was underlined with great attention. This way of

conveying knowledge is a useful service for different

types of students. All people involved in the design of

courses learned a lot and were aware of the new skills

acquired. The responses from students and the

increasing number of subscribed users suggest that

the all the work was done in the right way, even if

there are many suggestions for improvement, too.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Compagnia di San

Paolo, the main investor, for the economic support,

Rector of University of Turin Prof. G. Ajani, Dr. M.

Bruno and the staff of Board of Education and

Student Services, Ing. A. Saccà and the staff of Portal

Management, ICT services of the Computer Science

Department, the interdepartmental center

Cinedumedia, all professors, researchers and

technical-administrative staff at University of Turin

who collaborated in different ways.

REFERENCES

Baldoni, M., Cordero, A., Coriasco, S., Marchisio, M., 2011.

Moodle, Maple, MapleNet e MapleTA: dalla lezione alla

valutazione. In M. Baldoni, C. Baroglio, S. Coriasco, M.

Marchisio, and S. Rabellino (Eds.), E-Learning con

Moodle in Italia: una sfida tra presente, passato e futuro,

pp. 299-316. Torino, Italy: Seneca Edizioni.

Barana, A., Bogino, A., Fioravera, M., Floris, F., Marchisio,

M., Operti, L., Rabellino, S., 2017a. Self-paced approach

in synergistic model for supporting and testing students:

The transition from Secondary School to University,

Proceedings of 2017 IEEE 41st Annual Computer

Software and Applications Conference (COMPSAC),

pp. 404-409.

Barana, A., Bogino, A., Fioravera, M., Marchisio, M.,

Rabellino, S., 2016a. Digital Support for University

Guidance and Improvement of Study Results, Procedia -

Social and Behavioral Sciences, 228, pp. 547-552.

Barana, A., Bogino, A., Fioravera, M., Marchisio, M.,

Rabellino, S., 2017b. Open platform of self-paced

MOOCs for the continual improvement of academic

guidance and knowledge strengthening in tertiary

education, Journal of e-Learning and Knowledge

Society, 13(3), 109-119. doi:10.20368/1971-8829/1383

Barana, A., Conte, A., Fioravera, M., Marchisio, M.,

Rabellino, S., 2018. A Model of Formative Automatic

Assessment and Interactive Feedback for STEM,

Proceedings of 2018 IEEE 42nd Annual Computer

Software and Applications Conference (COMPSAC),

1016-1025. doi:10.1109/compsac.2018.00178

Barana, A., Fioravera, M., Marchisio, M., Rabellino, S.,

2017c. Adaptive teaching supported by ICTs to reduce

the school failure in the Project "Scuola dei Compiti",

Proceedings of 2017 IEEE 41st Annual Computer

Start@unito: Open Online Courses for Improving Access and for Enhancing Success in Higher Education

645

Software and Applications Conference (COMPSAC),

pp. 432-437. doi:10.1109/COMPSAC.2017.44

Barana, A., Marchisio, M., 2016b. Dall’esperienza di Digital

Mate Training all’attività di Alternanza Scuola Lavoro.

Mondo Digitale 15(64), pp. 63-82.

Barana, A., Marchisio, M., 2016c. Ten Good Reasons to

Adopt an Automated Formative Assessment Model for

Learning and Teaching Mathematics and Scientific

Disciplines. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences

228, pp. 608–613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro. 2016.

07.093

Barana, A., Marchisio, M., Rabellino, S., 2015. Automated

Assessment in Mathematics, COMPSAC Symposium on

Computer Education and Learning Technologies,

Taichung, 670-671. doi:10.1109/COMPSAC.2015.105

Barana, A., Marchisio, M., Sacchet, M., in press. Advantages

of the Use of Formative Automatic Assessment for

Learning Mathematics: In: Proceedings of 2018 TEA

Conference.

Brancaccio, A., Marchisio, M., Meneghini, C., Pardini, C.,

2015a. Matematica e Scienze più SMART per

l’Insegnamento e l’Apprendimento, MONDO

DIGITALE 14(58), pp. 1-8.

Brancaccio, A., Marchisio, M., Palumbo, C., Pardini, C.,

Patrucco, A., Zich, R., 2015b. Problem Posing and

Solving: Strategic Italian Key Action to Enhance

Teaching and Learning Mathematics and Informatics in

the High School. In: Proceedings of 2015 IEEE 39th

Annual Computer Software and Applications

Conference (COMPSAC), IEEE, Taichung, Taiwan, pp.

845–850. https://doi.org/10.1109/COMPSAC. 2015.126

Bruschi, B., Cantino, V., Cavallo Perin, R., Culasso, F.,

Giors, B., Marchisio, M., Marello, C., Milani, M., Operti,

L., Parola, A., Rabellino, S., Sacchet, M., Scomparin, L.,

2018. Start@unito: a Supporting Model for High School

Students Enrolling to University, Proceedings of the 15th

International conference on Cognition and Exploratory

Learning in Digital Age (CELDA 2018), Budapest, pp.

307-312.

Calise, M., Reda, V., 2017. In and Out. Federica experience

in the rugged terrain of MOOCs inclusion in institutional

strategies of university education. Proceedings of

EMOOCs 2017-WIP

Cinedumedia - Università degli Studi di Torino. Available at

http://www.cinedumedia.it/ (Accessed: 17 February

2019).

Coursera | Online Courses & Credentials by Top Educators.

Join for Free. Available at https://www.coursera.org/

(Accessed: 17 February 2019).

EasyReading. Available at http://www.easyreading.it/en/

(Accessed: 17 February 2019).

edX | Online courses from the world's best universities.

Available at https://www.edx.org/ (Accessed: 17

February 2019).

Giraudo, M.T., Marchisio, M., Pardini, C., 2014. Tutoring

con le nuove tecnologie per ridurre l’insuccesso

scolastico e favorire l’apprendimento della matematica

nella scuola secondaria. Mondo Digitale 13(51), pp. 834-

843.

Hattie, J., Timperley, H., 2007. The Power of Feedback.

Review of Educational Research 77(1), pp. 81–112.

https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

Hicks, S. D., 2011. Technology in today's classroom: Are you

a tech-savvy teacher?, The Clearing House, 84(5), pp.

188-191. doi:10.1080/00098655.2011.557406

Jordan, K., 2015. Massive Open Online Course Completion

Rates Revisited: Assessment, Length And Attrition.

10.13140/RG.2.1.2119.6963.

Kaltura Video Platform - Powering Any Video Experience.

Available at https://corp.kaltura.com/ (Accessed: 17

February 2019).

Nicol, D., Macfarlane-Dick, D., 2006. Formative assessment

and self-regulated learning: A model and seven

principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher

Education 31(2), pp. 199-218. doi:

10.1080/03075070600572090

Marchisio, M., Rabellino, S., Spinello, E., Torbidone, G.,

2017. Advanced e-learning for IT-Army officers through

Virtual Learning Eenvironments. Journal of e-Learning

and Knowledge Society 13(3), pp. 59–70.

https://doi.org/10.20368/1971-8829/1382

MERLOT. Available at https://www.merlot.org (Accessed:

17 February 2019).

Moebius Assessment. Available at https://www.digitaled.

com/products/assessment/index.aspx (Accessed: 17

February 2019).

Moodle - Open-source learning platform | Moodle.org.

Available at https://moodle.org/ (Accessed: 17 February

2019)

Relazione Annuale 2016, UniTo. Available at

https://www.unito.it/sites/default/files/relazione_annual

e_2016.pdf (Accessed: 17 February 2019).

Rogerson-Revell, P., 2007. Directions in e-learning tools and

technologies and their relevance to online distance

language education. Open Learning 22(1), pp. 57–74.

Ross, S., Morrison, G., Lowther, D., 2010. Educational

technology research past and present: balancing rigor and

relevance to impact learning, Contemporary Educational

Technology, 1(1), pp. 17-35. doi:10.4236/jss.2014.

22002

Rui, M., 2016. EduOpen: Italian Network for MOOCs, First

Three Months Evaluation after Initiation. Universal

Journal of Educational Research, 4 , pp. 2729 - 2734. doi:

10.13189/ujer.2016.041206.

Sadler, D.R., 1989. Formative assessment and the design of

instructional systems. Instructional Science 18(2), pp.

119–144.

Sangwin, C., 2015. Computer Aided Assessment of

Mathematics Using STACK. Springer, Cham. Selected

Regular Lectures from the 12th International Congress

on Mathematical Education, pp. 695-713. Springer

International Publishing.

Tomaševski, K., 2001. Human Rights Obligations: making

education available, accessible, acceptable and

adaptable, Right to education primers n. 3.

Who uses MOOCs and how?. Available at

http://monitor.icef.com/2014/07/who-uses-moocs-and-

how/ (Accessed: 17 February 2019).

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

646