Toward a Model of Workforce Training and Development

Maiju Tuomiranta

1

, Sanna Varpukari

1

and Nestori Syynimaa

2

1

Sovelto Plc, Helsinki, Finland

2

Faculty of Information Technology, University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä, Finland

Keywords: Learning Methods, Workforce, Training and Development, Formal Learning.

Abstract: In the modern, ever-changing world, both employers and employees are struggling in keeping their

competitive advantage. Previous studies have recognised that both formal instruction and informal learning

are needed to gain and maintain competence. The famous 70-20-10 model states that only 10 per cent of

learning occurs during the formal instruction. The challenge for the organisations is how the formal instruction

can and should be provided to employees. In this paper, we constructed a model of Workforce Training and

Development (WOTRA), based on the current learning theories, modes, methods, and models. WOTRA can

be used by both employers and employees to choose an adequate mix of learning modes and methods to

achieve their learning goals.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the modern world, where the speed of change is

higher than ever, employers are struggling in keeping

their employees’ skills current. Similarly, the

employees are concerned about how to gain and

maintain the right competence to remain compelling

in the labour market. The answer to both concerns is

workforce training and development (T&D).

There are three recognised ways to provide T&D:

formal and non-formal instruction, and informal

learning (Commission of the European Communities,

2001). The formal instruction, also known as

traditional instruction, refers to learning typically

occurring during instruction provided by an education

or training institution. Formal instruction is structured

and often aims to certification or a degree. Non-

formal instruction is similar to formal instruction

learning, except that it is not provided by an education

or training institution, and it does not lead to a

certificate or a degree. Learning in both formal and

non-formal instruction is conscious, i.e., intentional.

Informal learning, on the other hand, is not structured:

it means learning from daily life activities related to

work and leisure. As such, it is not instruction per se,

and the learning is not conscious as it “happens”

without intention.

Traditionally, education institutions have

provided education that satisfies the needs of the

labour market. Currently, there is a gap between

formal instruction and the labour market: education

institutions are not able to provide skilled employees

(World Economic Forum, 2017). To narrow this gap,

employers have been forced to rely on non-formal

instruction and informal learning.

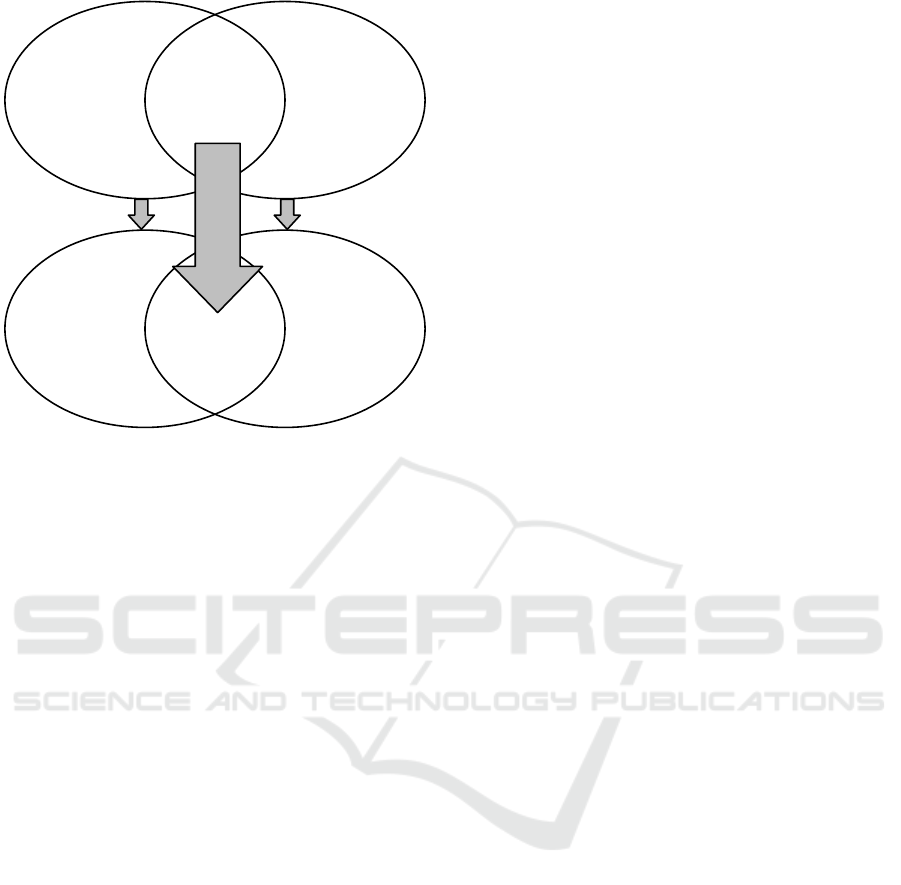

Informal learning alone, however, is not sufficient

to develop and maintain competence. Besides the

practical knowledge gain through informal learning,

also the theoretical competence from formal or non-

formal instruction is needed (Svensson, Ellström, and

Åberg, 2004). Theoretical and practical knowledge

together enables learning by reflection which, in turn,

develops the competence as illustrated in Figure 1.

It should be noted that learning at work is not

categorically informal (Billett, 2002). Also formal

and non-formal instruction can be used at work. The

challenge is, how the formal and non-formal

instruction can and should be provided to the

workforce?

In this paper, we introduce our preliminary model

for workforce training and development (WOTRA).

The model is based on the current learning models,

methods, and modes, as well as on the organisational

learning theories.

428

Tuomiranta, M., Varpukari, S. and Syynimaa, N.

Toward a Model of Workforce Training and Development.

DOI: 10.5220/0007756104280435

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2019), pages 428-435

ISBN: 978-989-758-367-4

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

Figure 1: Learning by reflection leads to competence

(adapted from Svensson et al., 2004).

2 METHOD

In this paper, we follow the Design Science Research

Process (DSRP) approach by Peffers, Tuunanen,

Rothenberger, and Chatterjee (2007) while building

the model. The problem identification and motivation

for the model is to enable formal and non-formal

instruction for the workforce. Our objective is to

allow the workforce to keep their competence current

now and in the future. The results of design and

development are reported in this paper as the

preliminary model. The rest of the phases of the

DSRP approach (i.e. demonstration and evaluation)

are out-of-scope of this paper and are left for future

research.

3 FROM INDIVIDUAL

LEARNING TO

ORGANISATIONAL

LEARNING

In the modern information-intensive world, the work

is often performed by self-organised teams (Hoda,

Noble, and Marshall, 2010). In such teams, the

education or title does not define the team members.

Instead, all team members are equal, and their

possible contribution to the team is defined by their

competence.

This implies that teams should be formed around

team members’ competences. In order to do this,

employers need to know their employees’

competence. Unfortunately, this is not often the case.

For instance, according to The Global Human Capital

Report (World Economic Forum, 2017), Finland was

number one on the development index in 2017. At the

same time, over 80 per cent of white-collar workers

think that their full capacity is not known by their

superiors (Taloustutkimus, 2017).

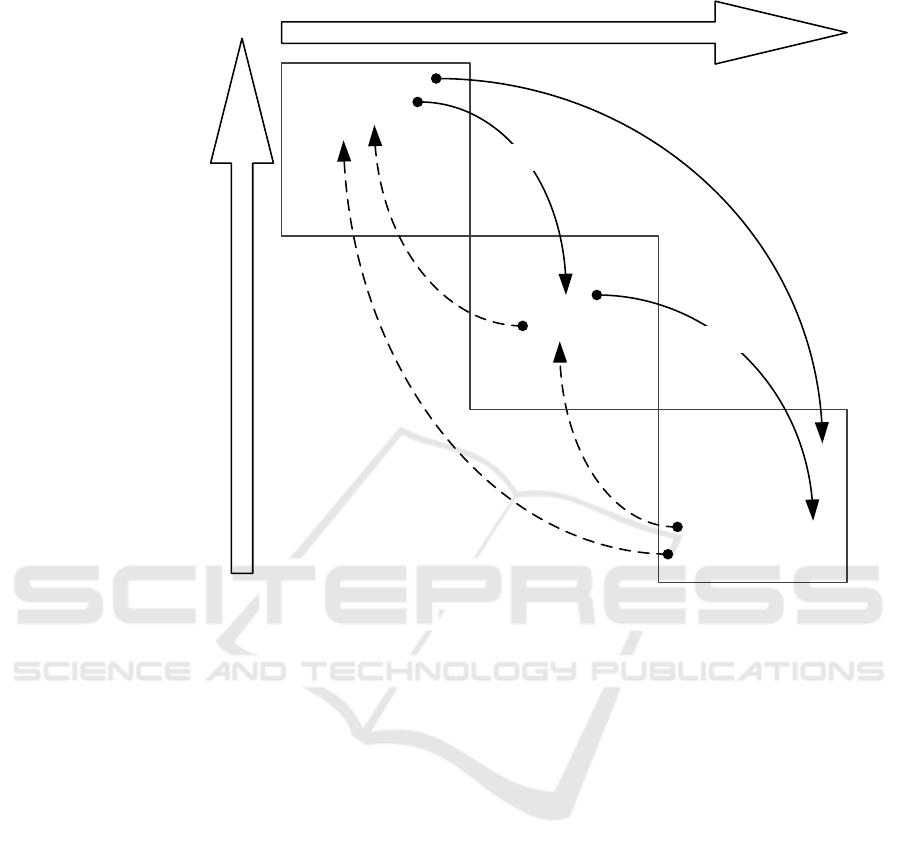

While individuals can learn from formal and non-

formal instruction, and by informal learning, the

organisations can only learn from their members (see

Figure 2). The feed-forward learning is a process

where organisation innovates and renews (Crossan et

al., 1999). The feedback learning process is opposite

to this: it reinforces what is already known (ibid.).

Organisational learning is the basis for success

when the knowledge comes more and more important

success factor. Indeed, the knowledge transfer has

been found to be a competitive advantage. However,

the knowledge in databases and information systems

is not enough; it needs to be connected to the right

people for learning to occur (Siemens, 2005). The

functional knowledge transfer is a competitive

advantage only if the knowledge stays inside the

organisation (Argote and Ingram, 2000). The only

situation where knowledge sharing outside the

organisation is regarded as a competitive advantage is

a cluster (regional or industry), where organisations

are learning from each other (Tallman, Jenkins,

Henry, and Pinch, 2004).

As already stated, the knowledge can be a

competitive advantage. But organisational learning is

a sustainable competitive advantage (Hatch and Dyer,

2004). Thus, the focus should be on organisational

learning. Organisations can promote learning by

using appropriate leadership styles. The transactional

leadership style can be used to promote feedback

learning (Vera and Crossan, 2004), which enhances

knowledge transfer and consequently strengthens the

gained competitive advantage. On the other hand, the

transformational leadership style can be used to

promote feed-forward learning (ibid.), which allows

the organisation to learn something new and thus

strengthen the organisation’s sustainable competitive

advantage.

Resilient organisations are learning organisations

that will maintain the high level of performance even

under external events, pressure, and uncertainties

(Boin and Van Eeten, 2013). The dilemma with

resilient organisations is that in theory, they shouldn’t

work, but in practise they do (LaPorte and Consolini,

1991).

Informal

learning

Learning by

reflection

Formal and

non-formal

instruction

Practical

knowledge

Competence

Theoretical

knowledge

Toward a Model of Workforce Training and Development

429

Figure 2: Organisational Learning as a Dynamic Process (Crossan, Lane, and White, 1999).

The organisational resiliency is defined as the ability

of the organisation to manifest itself after a surprising

danged, and as the ability of the organisation’s

management to quickly restore the order (Boin and

Van Eeten, 2013).

The building blocks of the resilient organisation

are resilient employees. In psychology, resilience

refers to “effective coping and adaptation although

faced with loss, hardship, or adversity” (Tugade and

Fredrickson, 2004, p. 320). In the work context, the

characteristics of the resilient employee are présence

d`esprit (calm, innovative, non-dogmatic thinking),

decisive action, tenacity, interpersonal

connectedness, honesty, self-control, and optimism

and positive perspective on life (Everly, McCormack,

and Strouse, 2012). All these characteristics are

learnable, so employees should thrive to learn these

to become and remain resilient.

4 70-20-10 MODEL

During the last decade, the 70-20-10 model has

received a lot of attention in organisations. It refers to

the division of where and how employees learn

(Kajewski and Madsen, 2012):

70% informal, on the job, experience-based,

stretch projects and practice.

20% coaching, mentoring, developing through

others.

10% formal learning interventions and

structured courses.

The model originates from a survey by Lombardo

and Eichinger (1996), where they studied

organisations’ top-management learning habits. The

model as such is not scientifically proven, but it is

arguably the most used model to explain how

employees learn in practice. The model combines

formal and non-formal instruction together with

informal learning. Thus, from theoretical point-of-

view, it can be used to develop employees’

competence.

Intuiting

Institutionalising

Individual Group Organisational

Individual

Group

Organisational

Feed forward

Feedback

Interpreting

Integrating

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

430

5 LIFELONG LEARNING

In the context of work life, lifelong learning means

that learning continues throughout employees’ career.

In this section, we will introduce some key concepts

related to lifelong learning.

Meta-skills are high-order skills required by other

skills. Ability to learn is the most important meta-

skill. The current leading learning theories, namely

behaviourism, cognitivism, and constructivism, are

interested in the learning process. However, these

theories are not interested in whether the learning is

valuable (Siemens, 2005). It has been argued, that

connectivism would be more suitable for explaining

the modern way of learning (Siemens, 2005).

Connectivism has been criticised in that it is not a

learning theory, but a pedagogical view (Duke,

Harper, and Johnston, 2013). Still, it is recognised

that understanding what is valuable to learn is

important (ibid.).

According to The Global Human Capital Report

(World Economic Forum, 2017), regardless of the

job, industry, education background or country, there

are two skills that are needed in the workplaces.

These skills are interpersonal skills and basic

technological skills.

6 LEARNING METHODS

6.1 Authentic Learning

Authentic learning refers to learning occurring during

formal and non-formal education, where the learning

setting is as authentic as possible. It covers things like

authentic real-world tasks and problems, and

simulations closely related to the studied field

(Nicaise, Gibney, and Crane, 2000). As such,

authentic learning provides elements from informal

learning to formal and non-formal instruction.

6.2 Problem-based Learning

Problem-based learning is similar to authentic

learning, as students are provided with an opportunity

to solve problems similar to what can be found in real-

life (Gallagher, Stepien, and Rosenthal, 1992). The

difference is that learning occurs by solving the

problems which are typically ill-structured. This

means that one or more problem elements are

unknown, they have unclear goals and unstated

constraints, possess multiple solutions, solution

paths, or no solutions at all, offer no general rules or

principles for describing or predicting most of the

cases and, require learners to make judgments about

the problem and defend them (Jonassen, 1997).

6.3 Flipped Learning

Flipped learning originates from flipped classroom,

where asynchronous videos and practice homework

were used together with active group-based solving in

the classroom (Bishop and Verleger, 2013).

Currently, flipped learning is seen as a learning-

centred approach where the teacher or educator

constantly evaluates the best way to use the class time

(Nederveld and Berge, 2015). As such, the very basic

and background information is provided outside the

class room using videos and other similar material.

All students are involved in the learning process, so

passive learning doesn’t exist in flipped learning

(ibid.).

6.4 Accelerated Learning

Accelerated learning programs are structured so that

students take less time to complete them than the

conventional training (Wlodkowski, 2003). It can be

defined as a “total system for speeding and enhancing

both the design process and the learning processes”

(The Center For Accelerated Learning, 2019).

Accelerated learning is ideal to the situations where

employees need to develop a totally new competence

in a relatively short period of time (weeks or months)

if compared to traditional vocational and university-

level education (years). However, if compared to

courses provided by commercial training

organisations (1-5 days), accelerated learning

requires much more time and commitment.

6.5 Micro-learning

Micro-learning (ML) combines micro-content

delivery with a sequence of micro-interactions which

enable users to learn without information overload

(Bruck, Motiwalla, and Foerster, 2012). Typically,

micro-learning takes only a couple of minutes at a

time. Micro-learning has found to be suitable for

professional development (Buchem and Hamelmann,

2010). Thus, it can be regarded as a pragmatic

solution for lifelong learning at work.

Toward a Model of Workforce Training and Development

431

7 LEARNING MODES

7.1 Instructor-led Training

Instructor-led training (ILT) is known as a

“traditional” mode of formal and non-formal

instruction, where the instructor has prepared a

structured learning experience. ILT is best suited to a

situation, where there is a need to study a totally new

competence.

If an instruction takes place face-to-face in

classrooms or at the workplace, instructors are able to

assess the learning constantly and change learning

methods as needed. The downside of face-to-face ILT

is that it requires a great amount of time from both

instructors and students.

7.2 Self-study

Self-study is a learning mode where students learn on

their own phase, without an instructor. The learning

material can be digital, such as videos and personal

learning environments, or more traditional, such as

books or practical work. Self-study can be structural,

with defined learning objectives, or free-form, where

students study without specific learning objectives.

Self-study is ideal for the situations where

learning is not time-bound, such as keeping the skills

current.

7.3 Blended Learning

Blended learning is a formal or non-formal

instruction mode which combines instructional

delivery media, instructional methods, and combines

online and face-to-face training (Graham, 2006). As

such, it can be a combination of ILT and self-study.

Blended-learning is ideal for the situation where

some degree of ILT is required. It is less time-

consuming than pure ILT but more time-bound than

pure self-study.

8 MODEL OF WORKFORCE

TRAINING AND

DEVELOPMENT

8.1 Preliminary Model

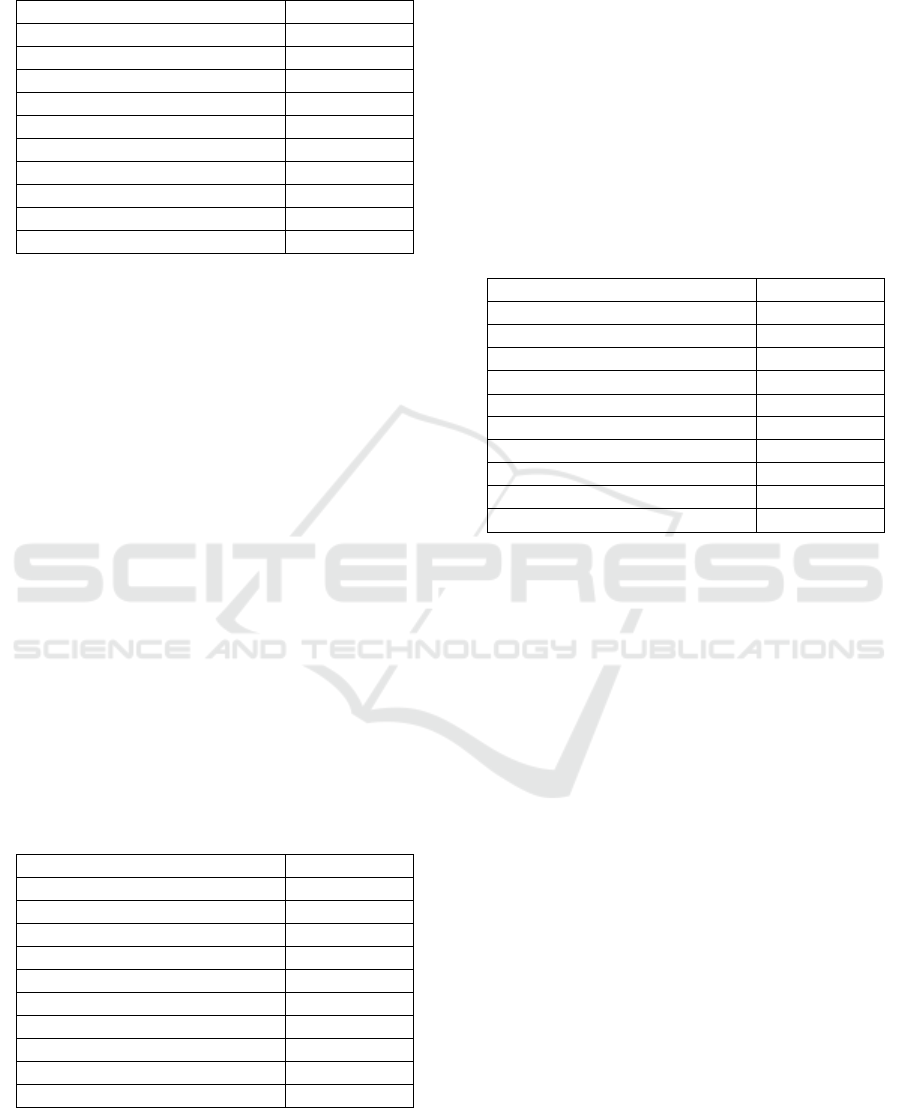

In this paper, we have introduced multiple learning

modes and methods. Each model and method is

suitable only for a limited number of learning

settings. Therefore, we propose the following model,

illustrated in Figure 3.

First, the learning goals should be defined. That

is, why and what to learn. Second, after defining the

learning goals, the suitable learning mode can be

chosen. Third, after the learning mode is chosen, the

suitable learning method or methods can be chosen.

As a result, the combination of learning goals, modes,

and methods together forms the best way to learn.

Figure 3: Model of Workforce Training and Development

(WOTRA).

8.2 Learning Goals

We have defined learning goals for the three

identified situations where employees require T&D.

The first situation is where an employee needs to keep

their professional skills current. The second one is

where the employee needs to keep their modern

workplace skills current. The third one is where the

employee needs to develop a totally new competence.

In the next sub-sections, we assess how different

learning methods and modes fit each of these learning

goals.

8.3 Keeping Professional Skills

Current

The fit of learning methods and modes for keeping

professional skills current are assessed in Table 1. As

the professional skills are likely to be relatively

complex to learn, the ILT and blended-learning

modes have the highest fit. In some cases, self-study

is justified but is assessed here as medium. This is

because without an instructor, assessing the learning

can be very difficult, if not impossible.

1: Learning

goals

2: Learning

modes

Best way

to learn

3: Learning

methods

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

432

Table 1: Fit of learning methods and modes for keeping

professional skills current.

FIT

LEARNING MODES

Instructor-led training

High

Self-study

Medium

Blended-learning

High

LEARNING METHODS

Authentic learning

High

Problem-based learning

High

Flipped learning

High

Accelerated learning

Low

Micro-learning

Medium

From the learning methods, authentic, problem-

based, and flipped learning was assessed as the

highest fit. This because, as already mentioned,

professional skills can be complex and should be

learned in as authentic setting as possible. Flipped

learning helps to focus the face-to-face instruction to

the most challenging subjects.

Accelerated learning is too time-consuming for

just keeping the skills current. Micro-learning might

be too “light” way to keep the skills current but is

justifiable in learning simple skills.

8.4 Keeping Modern Workplace Skills

Current

The fit of learning methods and modes for keeping

modern workplace skills current are assessed in Table

2. The modern workplace skills are not as complex as

professional skills. Therefore, self-study and

blended-learning modes were assessed as the highest

fit. ILT is too time-consuming but is justified in some

cases.

Table 2: Fit of learning methods and modes for keeping

modern workplace skills current.

FIT

LEARNING MODES

Instructor-led training

Medium

Self-study

High

Blended-learning

High

LEARNING METHODS

Authentic learning

Low

Problem-based learning

Low

Flipped learning

High

Accelerated learning

Low

Micro-learning

High

From learning methods, flipped and micro-

learning was assessed as highest fit. This is because

modern workplace skills are simpler than

professional skills, so these “lighter” methods are the

most adequate.

8.5 Developing a New Competence

The fit of learning methods and modes for developing

a new competence are assessed in Table 3. As

developing a new competence is the most complex

type of learning, ILT mode was assessed as the

highest fit. Self-study is too “light” mode to this, but

blended-learning might work in some settings.

Table 3: Fit of learning methods and modes for developing

a new competence.

FIT

LEARNING MODES

Instructor-led training

High

Self-study

Low

Blended-learning

Medium

LEARNING METHODS

Authentic learning

Medium

Problem-based learning

Medium

Flipped learning

Low

Accelerated learning

High

Micro-learning

Low

From the learning methods, only the accelerated

learning was assessed as high fit. Authentic and

problem-based learning may be suitable for some

settings but are less intensive methods.

9 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, we introduced a preliminary model of

Workforce Training and Development (WOTRA).

The model is based on the literature of current

learning theories, modes, methods, and models.

9.1 Limitations

According to the DSRP approach, all resulting

artefacts, such as WOTRA model, should be

accordingly validated. During the course of writing

this paper, this was not possible due to the tight

schedule.

9.2 Contributions to Practice

The WOTRA model helps both employers and

employees to choose the adequate mix of learning

modes and methods.

Toward a Model of Workforce Training and Development

433

9.3 Contributions to Science

Our preliminary WOTRA model is the first step

toward creating a model for workplace training and

development. As such, it is a starting point to foster

the scientific discussion related to this important area.

9.4 Directions for Future Research

The WOTRA model should next to be validated by

carefully studying organisations of different sizes and

industries.

REFERENCES

Argote, L., and Ingram, P. (2000). Knowledge transfer: A

basis for competitive advantage in firms.

Organizational behavior and human decision

processes, 82(1), 150-169.

Billett, S. (2002). Critiquing workplace learning discourses:

Participation and continuity at work. Studies in the

Education of Adults, 34(1), 56-67.

Bishop, J. L., and Verleger, M. A. (2013). The flipped

classroom: A survey of the research. Paper presented at

the ASEE national conference proceedings, Atlanta,

GA.

Boin, A., and Van Eeten, M. J. (2013). The resilient

organization. Public Management Review, 15(3), 429-

445.

Bruck, P. A., Motiwalla, L., and Foerster, F. (2012). Mobile

Learning with Micro-content: A Framework and

Evaluation. Bled eConference, 25.

Buchem, I., and Hamelmann, H. (2010). Microlearning: a

strategy for ongoing professional development.

eLearning Papers, 21(7), 1-15.

Commission of the European Communities. (2001).

Making a European area of lifelong learning a reality.

Communication from the Commission. COM (2001)

678 final, 21 November 2001.

Crossan, M. M., Lane, H. W., and White, R. E. (1999). An

organizational learning framework: from intuition to

institution. Academy of Management Review, 522-537.

Duke, B., Harper, G., and Johnston, M. (2013).

Connectivism as a Digital Age Learning Theory. In K.

Petrova, S. Lorraine, S. Tegginmath, and B. Todhunter

(Eds.), The International HETL Review. Special Issue.

(pp. 4-13). New York: The International HETL

Association.

Everly, G., McCormack, D., and Strouse, D. (2012). Seven

Characteristics of Highly Resilient People: Insights

from Navy SEALs to the 'Greatest Generation'.

International Journal of Emergency Mental Health,

14(2), 137-143.

Gallagher, S. A., Stepien, W. J., and Rosenthal, H. (1992).

The effects of problem-based learning on problem

solving. Gifted Child Quarterly, 36(4), 195-200.

Graham, C. R. (2006). Blended learning systems. In C. J.

Bonk and C. R. Graham (Eds.), The handbook of

blended learning (pp. 3-21): John Wiley & Sons.

Hatch, N. W., and Dyer, J. H. (2004). Human capital and

learning as a source of sustainable competitive

advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 25(12),

1155-1178.

Hoda, R., Noble, J., and Marshall, S. (2010, 2-8 May 2010).

Organizing self-organizing teams. Paper presented at

the 2010 ACM/IEEE 32nd International Conference on

Software Engineering.

Jonassen, D. H. (1997). Instructional design models for

well-structured and III-structured problem-solving

learning outcomes. Educational technology research

and development, 45(1), 65-94.

Kajewski, K., and Madsen, V. (2012). Demystifying

70:20:10 White Paper. Melbourne: DeakinPrime.

LaPorte, T. R., and Consolini, P. M. (1991). Working in

Practice but Not in Theory: Theoretical Challenges of

"High-Reliability Organizations". Journal of Public

Administration Research and Theory: J-PART, 1(1),

19-48.

Lombardo, M. M., and Eichinger, R. W. (1996). The Career

Architect Development Planner. Minneapolis:

Lominger.

Nederveld, A., and Berge, Z. L. (2015). Flipped learning in

the workplace. Journal of Workplace Learning, 27(2),

162-172.

Nicaise, M., Gibney, T., and Crane, M. (2000). Toward an

Understanding of Authentic Learning: Student

Perceptions of an Authentic Classroom. Journal of

Science Education and Technology, 9(1), 79-94.

doi:10.1023/a:1009477008671

Peffers, K., Tuunanen, T., Rothenberger, M. A., and

Chatterjee, S. (2007). A Design Science Research

Methodology for Information Systems Research.

Journal of management information systems, 45-77.

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A learning theory for

the digital age. International journal of Instructional

Technology & Distance Learning, 2(1).

Svensson, L., Ellström, P. E., and Åberg, C. (2004).

Integrating formal and informal learning at work.

Journal of Workplace Learning, 16(8), 479-491.

doi:doi:10.1108/13665620410566441

Tallman, S., Jenkins, M., Henry, N., and Pinch, S. (2004).

Knowledge, clusters, and competitive advantage.

Academy of Management Review, 29(2), 258-271.

Taloustutkimus. (2017). Made By Finland campaign -

Final report Retrieved from

https://suomalainentyo.fi/wp-

content/uploads/2018/01/made-by-finland-

tutkimusraportti-tiivistelma.pdf

The Center For Accelerated Learning. (2019). What is

accelerated learning? Retrieved from

https://www.alcenter.com/about-us/about-a-l/

Tugade, M. M., and Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). Resilient

individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from

negative emotional experiences. Journal of personality

and social psychology, 86(2), 320.

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

434

Vera, D., and Crossan, M. (2004). Strategic Leadership and

Organizational Learning. The Academy of Management

Review, 29(2), 222-240. doi:10.2307/20159030

Wlodkowski, R. J. (2003). Accelerated learning in colleges

and universities. New Directions for Adult and

Continuing Education, 2003(97), 5-16.

World Economic Forum. (2017). The Global Human

Capital Report 2017. Retrieved from

https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-human-

capital-report-2017

Toward a Model of Workforce Training and Development

435