A Framework for Measuring the Costs of Security at Runtime

Igor Ivkic

1,2

, Harald Pichler

2

, Mario Zsilak

2

, Andreas Mauthe

1

and Markus Tauber

2

1

Lancaster University, Lancaster, U.K.

2

University of Applied Sciences Burgenland, Eisenstadt, Austria

Keywords:

Cyber-Physical Systems, Internet of Things, Component Monitoring, Task Tracing, Security Cost Modelling.

Abstract:

In Industry 4.0, Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS) are formed by components, which are interconnected with each

other over the Internet of Things (IoT). The resulting capabilities of sensing and affecting the physical world

offer a vast range of opportunities, yet, at the same time pose new security challenges. To address these chal-

lenges there are various IoT Frameworks, which offer solutions for managing and controlling IoT-components

and their interactions. In this regard, providing security for an interaction usually requires performing addi-

tional security-related tasks (e.g. authorisation, encryption, etc.) to prevent possible security risks. Research

currently focuses more on designing and developing these frameworks and does not satisfactorily provide

methodologies for evaluating the resulting costs of providing security. In this paper we propose an initial

approach for measuring the resulting costs of providing security for interacting IoT-components by using a

Security Cost Modelling Framework. Furthermore, we describe the necessary building blocks of the frame-

work and provide an experimental design showing how it could be used to measure security costs at runtime.

1 INTRODUCTION

In recent years, cloud computing has changed the way

how computer resources are being managed, config-

ured, accessed, and used (Mell et al., 2011). At the

same time, it paved the way towards the fourth in-

dustrial revolution (Industry 4.0), which is driven by

Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS) and the Internet of

Things (IoT) (Hermann et al., 2016; Almada-Lobo,

2016). A CPS is formed by a number of components

(e.g. IoT-components), which are interconnected over

the IoT and are capable of sensing and affecting the

physical world (Esterle and Grosu, 2016). Conse-

quently, the swarm of interacting components tends

to quickly become complex and challenging to ad-

minister. To address this challenge, various frame-

works (Derhamy et al., 2015) offer solutions to the

management of IoT-components entering a CPS (Bi-

caku et al., 2018a) and to control how they interact

with other components in a secure manner.

Within an interaction a number of components

perform different tasks and communicate with each

other to serve a specific purpose. To provide secu-

rity for these interactions, the execution of additional

(security-related) tasks, which are not directly linked

to the purpose of the interaction, is required. For in-

stance, as shown in Figure 1 the purpose of the in-

teraction is to measure the temperature of a physical

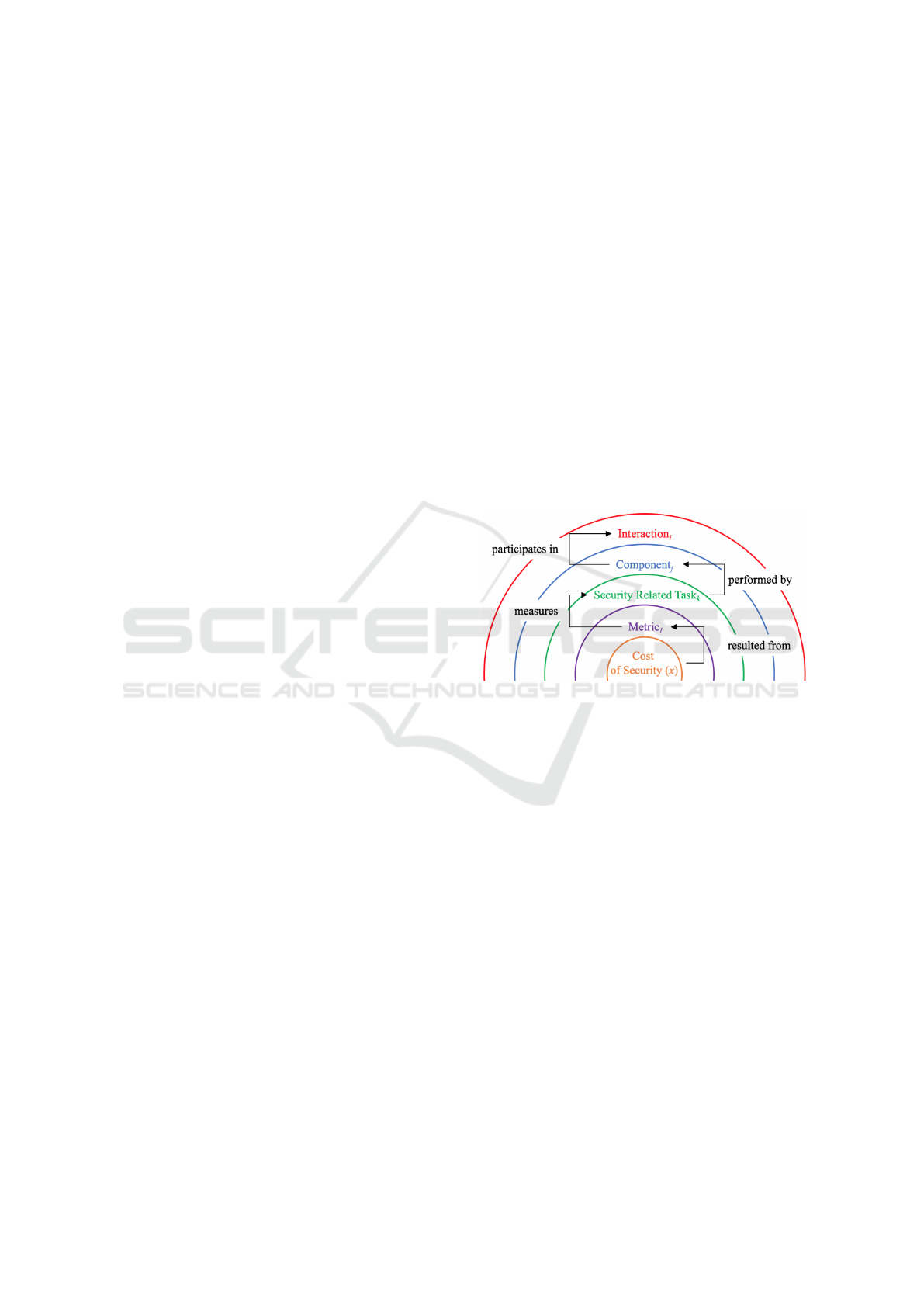

Figure 1: Security Cost Modelling Framework.

room (C

2

) and to cool it down if necessary (C

1

). To

provide security for this interaction, the IoT Frame-

work ensures that only C

1

and C

2

are authorised to

exchange room temperature data to control the air-

488

Ivkic, I., Pichler, H., Zsilak, M., Mauthe, A. and Tauber, M.

A Framework for Measuring the Costs of Security at Runtime.

DOI: 10.5220/0007761604880494

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Cloud Computing and Services Science (CLOSER 2019), pages 488-494

ISBN: 978-989-758-365-0

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

conditioning system. Additionally, before any data

is transmitted between the components, they encrypt

their messages to avoid eavesdropping attacks. These

additional steps (authorisation and encryption) are

mainly security-related tasks, which are not directly

linked to the purpose of the interaction and produce

costs (e.g. execution time, computing resources, etc.).

Due to the complexity of interactions, the num-

ber of participating components and performed tasks,

an approach is needed to measure how much it costs

for providing security at runtime. Measuring security

costs of an interaction enables (i) redesigning inter-

actions to produce less security-related costs, (ii) pre-

dicting future security costs based on past measure-

ments, and (iii) detecting anomalies based on the ex-

pected security costs in comparison to actually mea-

sured security costs of an interaction. To address

this challenge, we propose an initial approach to au-

tomatically measure the resulting costs of providing

security by using a Security Cost Modelling Frame-

work as shown in Figure 1. The proposed framework

is an extension of our previous work (Ivkic et al.,

2019), where we proposed an Onion Layer Model,

which formally describes a CPS including its inter-

actions, the participating components and their per-

formed tasks.

In this paper, we extend the Onion Layer Model

by proposing a Security Cost Modelling Framework,

which uses additional mechanisms to collect data

about the interacting components (Component Moni-

toring) and their performed tasks (Task Tracing). The

gathered runtime data is then combined with a Cost

Metric Catalogue, which contains security cost met-

rics and is used to measure the security-related tasks

performed by components during interactions. Fur-

thermore, we extend the Onion Layer Model to be

able to measure security costs at a specific point in

time, explain how these mechanisms could be used

in a harness for measuring security costs and discuss

how they can be implemented.

The remainder of this paper is organised as fol-

lows: Section II summarises the related work in the

field and presents the background of this paper. Next,

in Section III, we present a use case for measuring

and controlling the temperature of a physical room.

Based on that we present the Security Cost Modelling

Framework and explain the building blocks needed to

measure security costs at runtime. Finally, in Section

IV we give an outline of future work in the field.

2 RELATED WORK

There are various approaches, platforms and frame-

works supporting the CPS and IoT movement. Derha-

my et al. (2015) summarise commercially avail-

able IoT frameworks including the IoTivity frame-

work (IoTivity, 2015), the IPSO Alliance framework

(Shelby and Chauvenet, 2012), the Light Weight Ma-

chine to Machine (LWM2M) framework (Alliance,

2012), the AllJoyn framework (Alliance, 2016) and

the Smart Energy Profile 2.0 (SEP2.0) (Alliance and

Alliance, 2013). Most of the cloud-based frameworks

follow a data-driven architecture in which all involved

IoT-components are connected to a global cloud using

one SOA protocol. The Arrowhead Framework (Dels-

ing, 2017), on the contrary, follows an event-driven

approach, in which a local cloud is governed through

the use of core systems for registering and discovering

service, authorisation and orchestration. Since every-

thing within an Arrowhead Local Cloud is a service,

new supporting systems can be developed and added

to the already existing ones.

Regarding cyber security, there are many studies

proposing approaches and frameworks which focus

on evaluating security without referring to the result-

ing costs. Additionally, some of the presented ap-

proaches are limited by the usage of a single met-

ric, like process performance in Dumas et al. (2013),

and Gruhn and Laue (2006). Even though this metric

could help to estimate the costs of security it is mainly

used to evaluate the process of software implementa-

tion. Other related work focuses on methods for mea-

suring how secure a specific system is by evaluating

whether a security control has been implemented or

not (Hayden, 2010; Pfleeger, 2009; Tariq, 2012; Luna

et al., 2011). Unfortunately, these approaches provide

little insight into how to measure the costs of security.

Yee (2013) provides a summary of related work re-

garding security metrics. He first explains that many

security metrics exist, but most of them are ineffective

and not meaningful. Furthermore, the author provides

a definition of a good and a bad metric and applies

his definition on various frameworks in a literature re-

search.

This paper builds on Ivkic et al. (2019) where we

introduce an Onion Layer Model for formally describ-

ing how the costs of security can be modelled within a

CPS. This initial investigation included a mathemati-

cal expression for describing the costs of security dur-

ing the interaction of components and their performed

security-related tasks. Additionally, we showed how

the Onion Layer Model could be used to evaluate the

costs of security for two specific use cases in an ex-

emplary evaluation. To extend this work the key new

contribution of this paper is to present an approach for

automatically identifying the components of an inter-

action and their performed tasks at runtime. Further-

more, we extend the previous mathematical expres-

A Framework for Measuring the Costs of Security at Runtime

489

sion by transforming it to consider time including a

metric catalogue, allowing modelling the costs of se-

curity for interactions over a period of time. This al-

lows applying the Onion Layer Model over a longer

period of time to be able to measure, compare and

analyse the costs of security of a CPS at runtime.

3 DISCUSSION ON MODELLING

SECURITY COSTS

In this section we present the Security Cost Modelling

Framework and its building blocks, which are neces-

sary to measure security costs at runtime. First, we

present a use case where a component with a sen-

sor, another component with an actuator and an IoT

Framework are interacting with each other. Based

on that use case we then propose a framework and

discuss how it could be used to measure the security

costs at runtime. The proposed framework in Figure

1 includes the Onion Layer Model from our previ-

ous work, which uses additional mechanisms in order

to identify communicating components and their per-

formed tasks at runtime. In addition to that the frame-

work also uses a Cost Metric Catalogue for measuring

the cost of security.

3.1 Closed-loop Temperature Control

In many respects, the closed-loop control view in Fig-

ure 1 corresponds to the most fundamental defini-

tion of a CPS. One component (C

1

) uses a sensor to

measure the physical world, while another component

(C

2

) uses this information to change it. Based on that

the following use case consists of a component, which

uses a temperature sensor to measure a room’s tem-

perature (C

1

), while another component controls an

air-conditioning system (C

2

) to control it. First, C

1

becomes part of an existing CPS by registering the

temperature sensor to the IoT Framework (step 1).

Next, before C

2

decides whether the room needs to be

cooled down, it sends a request to the IoT Framework

asking for a component which is capable of measur-

ing the room’s temperature (step 2). However, be-

fore the IoT Frameworks returns the endpoint of such

a component it verifies whether C

2

is authorised for

such an interaction (step 3). If it is, the next step is

to search the component registries (step 4) and return

the temperature sensor component (step 5). After that

C

2

requests in a loop the room temperature from C

1

(step 6), which uses the sensor to measure it and re-

turns the measured value (step 7). Finally, C

2

verifies

if a limit has been reached (e.g. greater than 25 de-

grees Celsius) and decides whether to activate the air-

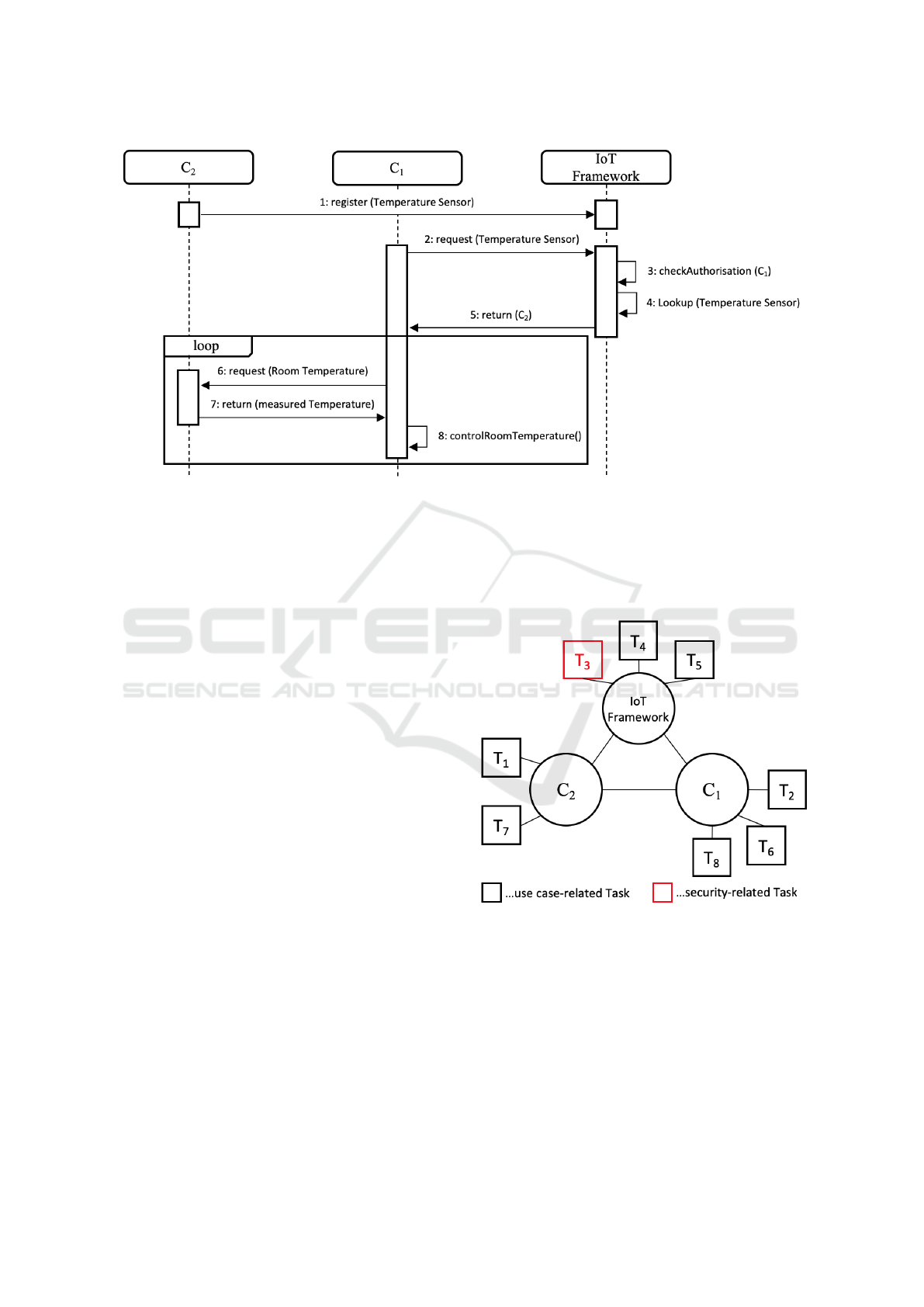

conditioning system or not (step 8). Figure 3 shows

the sequence diagram including all steps of the de-

scribed Closed-Loop Temperature Control use case.

3.2 Security Cost Modeling Framework

The Onion Layer Model from from Ivkic et al.

(2019), as shown in Figure 2, can be used to describe

security costs that occur each time an interaction is

executed. In this context, an interaction is defined as

a unit of work, which is executed at a specific time,

serves a specific purpose and can be treated in an co-

herent and reliable way independent of other interac-

tions. Furthermore, it includes one or more partici-

pating components that perform a number of differ-

ent tasks. In relation to the use case in Figure 3 the

Closed-Loop Temperature Control represents an in-

teraction that involves three components (C

1

, C

2

, IoT

Framework), which perform a total of seven tasks.

Figure 2: Onion Layer Model for Modelling Security Costs.

To measure the security costs of all interactions

the Onion Layer Model in Figure 2 suggests to form

a sum of sums. The first sum (

∑

n

i=1

) represents all ex-

isting interactions of a CPS, while the second (

∑

m

j=1

)

summarizes all components within one interaction.

The next sum (

∑

o

k=1

) aggregates all security-related

tasks which have been performed by a one compo-

nent. Finally, the last sum (

∑

p

l=1

) adds up all metrics

which have been used to measure the performance of

a specific security-related task. In our previous work

(Ivkic et al., 2019) the sum of sums has only been

used to describe how the cost of security could be

modelled within a CPS.

f

t

=

n

∑

i=1

m

∑

j=1

o

∑

k=1

p

∑

l=1

x

t

i jk l

(1)

Now, to extend this work and to be able to ag-

gregate the security costs at a specific point in time

the approach has been extended by a time function

f

t

as shown in (1). This allows measuring a spe-

cific security-related task performed by a component,

which participates in an interaction at a specific point

CLOSER 2019 - 9th International Conference on Cloud Computing and Services Science

490

Figure 3: Sequence Diagram for the Closed-Loop Temperature Control Use Case.

in time. Furthermore, measuring the same task pe-

riodically allows aggregating the temporal course of

security costs for this task.

To measure the security costs of an interaction

as they are occurring, the Onion Layer Model needs

to know the participating components, the performed

tasks and which metrics need to be used. As shown in

Figure 1, a Component Monitoring mechanism could

listen to the Internet Protocol (IP) address and port of

all components. Each time a component sends a mes-

sage to another one, the mechanism would create a

record containing at least the date and time, the send-

ing and receiving endpoints (sender/receiver IP and

port). Similar to that a Task Tracing mechanism could

log the performed tasks for each component. Addi-

tionally, this mechanism should categorize all tasks in

use case-related and security-related tasks. Finally, a

Cost Metric Catalogue could provide a set of metric

types which can be used to measure the security costs

of the previously identified security-related tasks. The

combination of the presented mechanisms (Compo-

nent Monitoring, Task Tracing), the Cost Metric Cat-

alogue and the Onion Layer Model in (1) allows mea-

suring the security costs of interactions at runtime.

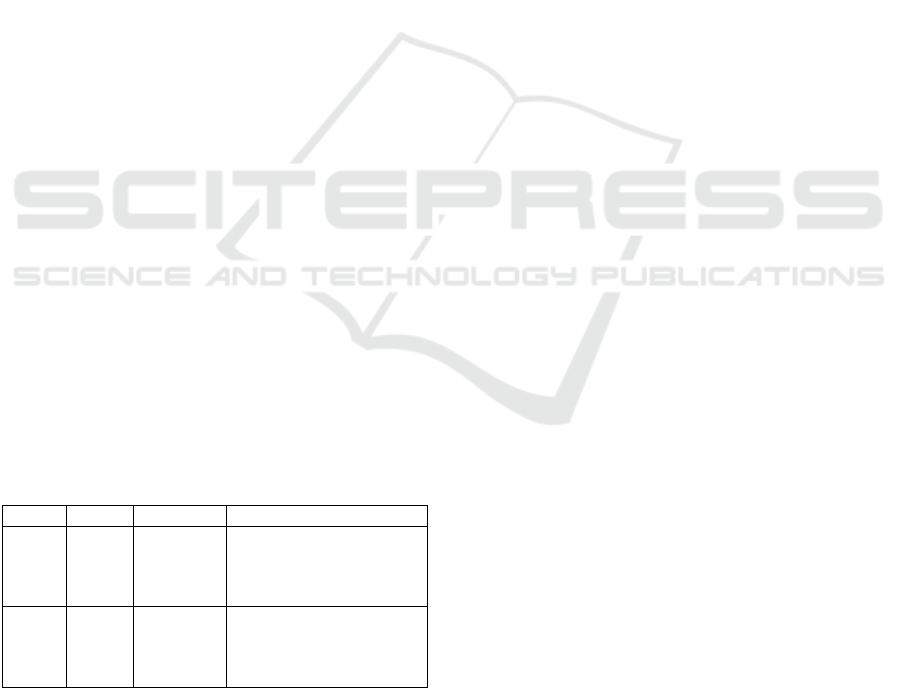

Another interesting aspect of the proposed ap-

proach is that the measured runtime data could be

used to visualize an interaction, its participating com-

ponents and their performed tasks. Over time, an

interaction with all its components can quickly be-

come incomprehensible, making it difficult for peo-

ple to keep track of what is going on. To solve this

problem the measured runtime data of ”which compo-

nent communicates with which” and ”which compo-

nent performs which tasks and when” could be used

to create a simpler and more comprehensible graph.

For instance, Figure 4 shows a possible visual rep-

resentation of the Closed-Loop Temperature Control

interaction including its participating components and

their performed tasks: This graph enables the visual-

Figure 4: Visual Representation of an Interaction.

isation of interactions while they are happening and

improves their comprehensibility. Additionally, the

graph makes possible the comparison of interactions

and identification of performance issues (e.g. bottle-

necks).

3.3 Intended Experimental Design

To measure security costs in an experimental study

the Closed-Loop Temperature Control use case will

A Framework for Measuring the Costs of Security at Runtime

491

be implemented and evaluated. For the implemen-

tation we are planning to use a representative IoT

Framework which is capable of registering and dis-

covering services and verifying requests for authori-

sation. The Arrowhead Framework (Delsing, 2017)

could be a possible candidate, since its Core Services

(Service Registry, Authorisation and Orchestration)

already provide some of the required functionalities.

Regarding other requirements (Component Monitor-

ing, Task Tracing) further investigation of the frame-

work is needed to identify whether it already pro-

vides the necessary mechanisms, or if they need to

be implemented, yet. Furthermore, we plan to ex-

ecute the Closed-Loop Temperature Control interac-

tion consecutively in a loop of n runs (e.g. n = 50

runs) using two different workloads (WL). In W L

1

a

representative security messaging protocol (S) will be

used to support an encrypted communication between

the components (C

1

and C

2

) and the IoT Framework,

while W L

2

will use an insecure protocol (I). In a first

evaluation we are planning to use a representative set

of the following four metrics for measuring the per-

formed tasks for each run:

• M

1

: duration in milliseconds (ms)

• M

2

: Central Processing Unit (CPU)-usage in per-

cent (%)

• M

3

: Read Access Memory (RAM)-usage in

Megabyte (MB)

• M

4

: packet-size of data packages in Kilobyte

(KB)

The following table summarises the setup of the

planned experimental evaluation including the two

WLs (W L

1

, W L

2

), the number of runs (n) , the used

messaging protocols (secure protocol = S, insecure

protocol = I) per WL and the metrics for measuring

the performed tasks (M

1

, M

2

, M

3

, M

4

):

Table 1: Workloads for Experimental Evaluation.

WL

∗

Runs Protocol Metrics

W L

1

n S

M

1

: duration (ms)

M

2

: CPU-usage (%)

M

3

: RAM-usage (MB)

M

4

: packet-size (KB)

W L

2

n I

M

1

: duration (ms)

M

2

: CPU-usage (%)

M

3

: RAM-usage (MB)

M

4

: packet-size (KB)

∗

Workloads

The runtime information provided by the Component

Monitoring and Task Tracing mechanisms at runtime

will be used during the experimental evaluation in

combination with the Onion Layer Model. The idea

is to use the representative metrics to measure each

performed task of a component for each run. Then,

the following aggregation can be done to measure the

costs of using a messaging protocol (P = {S, I}) for

each run (n = 50) and each metric (m = 4):

x

P

(i) =

n

∑

i=1

m

∑

j=1

M

j

(i) (2)

As shown in (2) x

P

(i) represents the aggregation of

the measured costs of using protocol P for run i, while

M

j

(i) represents the metric j used to measure the

costs for each run. Now, as shown in (3) the secu-

rity costs (x

SC

) can be calculated by the differenc be-

tween the two aggregations of using the secure proto-

col x

S

(i) and the insecure protocol x

I

(i):

x

SC

(i) =

n

∑

i=1

x

S

(i) − x

I

(i) (3)

4 FUTURE WORK

4.1 Implementation & Evaluation

As mentioned in the previous section we will im-

plement the Closed-Loop Temperature Control use

case and evaluate its security costs in an experimen-

tal study. In this regard we will first investigate a

representative IoT Framework, which preferably al-

ready includes most of the required functionalities

and mechanisms implemented. In addition to that the

selected IoT Framework has to be extensible in or-

der to be able to implement missing mechanism and

functionalities. Once the use case is implemented we

will conduct an experimental study as described in 3.3

using the predefined WLs, protocols (S, I) and repre-

sentative metrics (M

1

, M

2

, M

3

, M

4

).

4.2 Normalisation & Conversion

Even though the presented Security Cost Modelling

Framework suggests evaluating security costs at run-

time, it implies using metrics with measurement re-

sults which can be aggregated. In other words, M

1

provides results, which cannot be aggregated with the

other metrics. Due to incompatible units, a metric

measuring the duration in ms cannot directly be ag-

gregated with another metric measuring the load of a

CPU in %. Another problem is that when using two or

more metrics with different units the results may need

to be interpreted. For instance, when using all four of

the proposed metrics in two runs the measurements

might provide the following results:

CLOSER 2019 - 9th International Conference on Cloud Computing and Services Science

492

• x

1

= 5 ms + 10 % + 5 MB + 10 KB

• x

2

= 10 ms + 5% + 10 MB + 5 KB

• is x

1

< x

2

or x

1

> x

2

Without normalisation of the results it is impos-

sible to tell which of the two measurements is ”bet-

ter” or ”cheaper” in terms of security costs. There-

fore, when using a metric catalogue in combination

with the Security Cost Metric Framework we need a

method for either normalising or converting measure-

ment results to a general Cost Unit.

4.3 Security Costs & Compliance

As already mentioned, monitoring communicating

components, tracing their performed tasks and mea-

suring resulting security costs opens up many new

possibilities. However, the security costs of e.g. two

systems, or two interactions (which serve the same

purpose) cannot be directly compared without know-

ing how secure the system or the interaction is. For

instance, if System

A

and System

B

produce the same

security costs for the same tasks they have performed,

it does not directly imply that they have the same level

of security. System

A

might be using a less secure algo-

rithm for encrypting its messages than System

B

. So,

in order to make those two systems comparable in re-

gard to security costs it is also necessary to evaluate

how secure both systems are.

Bicaku et al. (2018b) proposed a Monitoring

and Standard Compliance Verification Framework,

where they monitor whether a specific security con-

trol has been implemented/activated on the target sys-

tem. Furthermore, they propose to first extract the se-

curity controls from established standards and then

provide a mechanism how to monitor if they have

been implemented/activated. A combination of the

Security Costs Modelling Framework and the Mon-

itoring and Standard Compliance Verification Frame-

work from Bicaku et al. (2018b) could be used to

make two systems comparable in regard of security

costs and security compliance. We will investigate

these two approaches and verify whether it is possible

to combine them in future work.

5 CONCLUSION

In this paper, we presented a framework, which can

be used to measure security costs at runtime. We first

presented a close-to-reality use case, which uses an

IoT-component to measure the physical world (C

1

us-

ing a temperature sensor) and another one to affect

it (C

2

controlling an air-conditioning system). In ad-

dition to that an IoT Framework is integrated in this

use case, which manages service lookup and autho-

risation requests. Next, we presented the Security

Cost Modelling Framework, which is an extension of

our previous work and explain the missing building

blocks (Component Monitoring, Task Tracing, Cost

Metric Catalogue) to be able to measure the security

costs at runtime. Finally, we describe how we intend

to evaluate the security costs of the presented use case

in an experimental study. This included the design of

the experiment, the description of the WLs, runs (n),

protocols (S, I) and representative metrics (duration,

CPU-usage, RAM-usage, packet-size). Furthermore,

we showed how the costs of security will be estimated

at runtime by putting all building blocks of the pre-

sented Security Cost Modelling Framework together.

The main contribution of this paper is a frame-

work, which can be used to measure security costs

at runtime. This Security Cost Modelling Frame-

work will be enhanced by conducting an experimental

study as described in Section 3.3 in future work. Fur-

thermore, we will implement the Security Cost Mod-

elling Framework, which uses the outputs of the pro-

posed mechanisms to measure the security costs of

the closed-loop temperature control interaction at run-

time. Summarising, the main goal is to develop the

Security Cost Modelling Framework, which identifies

the interacting components and their performed tasks

of an interaction at runtime and measures the resulting

costs of providing security.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Research leading to these results has received fund-

ing from the EU ECSEL Joint Undertaking under

grant agreement n737459 (project Productive4.0) and

from the partners national programs/funding authori-

ties and the project MIT 4.0 (FE02), funded by IWB-

EFRE 2014 - 2020 coordinated by Forschung Burgen-

land GmbH.

REFERENCES

Alliance, A. (2016). Alljoyn framework. Linux

Foundation Collaborative Projects. URl:

https://allseenalliance.org/framework (visited on

09/14.

Alliance, O. M. (2012). Lightweight machine to machine

architecture. Draft Version, 1:1–12.

Alliance, Z. and Alliance, H. (2013). Smart energy profile 2

application protocol standard. document 13–0200-00.

A Framework for Measuring the Costs of Security at Runtime

493

Almada-Lobo, F. (2016). The industry 4.0 revolution and

the future of manufacturing execution systems (mes).

Journal of innovation management, 3(4):16–21.

Bicaku, A., Maksuti, S., Heged

˝

us, C., Tauber, M., Dels-

ing, J., and Eliasson, J. (2018a). Interacting with the

arrowhead local cloud: On-boarding procedure. In

2018 IEEE Industrial Cyber-Physical Systems (ICPS),

pages 743–748. IEEE.

Bicaku, A., Schmittner, C., Tauber, M., and Delsing,

J. (2018b). Monitoring industry 4.0 applications

for security and safety standard compliance. In

2018 IEEE Industrial Cyber-Physical Systems (ICPS),

pages 749–754. IEEE.

Delsing, J. (2017). Iot automation: Arrowhead framework.

CRC Press.

Derhamy, H., Eliasson, J., Delsing, J., and Priller, P. (2015).

A survey of commercial frameworks for the inter-

net of things. In IEEE International Conference

on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation:

08/09/2015-11/09/2015. IEEE Communications Soci-

ety.

Dumas, M., La Rosa, M., Mendling, J., and Reijers, H. A.

(2013). Introduction to business process management.

In Fundamentals of Business Process Management,

pages 1–31. Springer.

Esterle, L. and Grosu, R. (2016). Cyber-physical systems:

challenge of the 21st century. e & i Elektrotechnik und

Informationstechnik, 133(7):299–303.

Gruhn, V. and Laue, R. (2006). Complexity metrics for

business process models. In 9th international con-

ference on business information systems (BIS 2006),

volume 85, pages 1–12. Citeseer.

Hayden, L. (2010). IT security metrics: A practical

framework for measuring security & protecting data.

McGraw-Hill Education Group.

Hermann, M., Pentek, T., and Otto, B. (2016). Design prin-

ciples for industrie 4.0 scenarios. In System Sciences

(HICSS), 2016 49th Hawaii International Conference

on, pages 3928–3937. IEEE.

IoTivity, I. (2015). A linux foundation collaborative project.

Ivkic, I., Mauthe, A., and Tauber, M. (2019). Towards a se-

curity cost model for cyber-physical systems. In 2019

16th IEEE Annual Consumer Communications & Net-

working Conference (CCNC), pages 1–7. IEEE.

Luna, J., Ghani, H., Germanus, D., and Suri, N. (2011).

A security metrics framework for the cloud. In Secu-

rity and Cryptography (SECRYPT), 2011 Proceedings

of the International Conference on, pages 245–250.

IEEE.

Mell, P., Grance, T., et al. (2011). The nist definition of

cloud computing.

Pfleeger, S. L. (2009). Useful cybersecurity metrics. IT

professional, 11(3):38–45.

Shelby, Z. and Chauvenet, C. (2012). The ipso applica-

tion framework draft-ipso-app-framework-04. Ava-

iable online: http://www. ipso-alliance. org/wp-

content/media/draft-ipso-app-framework-04. pdf (ac-

cessed on 3 June 2014).

Tariq, M. I. (2012). Towards information security met-

rics framework for cloud computing. International

Journal of Cloud Computing and Services Science,

1(4):209.

Yee, G. O. (2013). Security metrics: An introduction and

literature review. In Computer and Information Secu-

rity Handbook (Second Edition), pages 553–566. El-

sevier.

CLOSER 2019 - 9th International Conference on Cloud Computing and Services Science

494