Using Learning Analytics within an e-Assessment Platform for a

TransFormative Evaluation in Bilingual Contexts

Samira ElAtia

1,*

and Eivenlour David

2

1

Division of Education, The University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

2

Department of Computing Sciences, Faculty of Sciences, The University of Alberta, Canada

Keywords: Longitudinal Bilingual Evaluation, TransFormative Assessment, Learner’s Engagement, Learning

Analytics.

Abstract: Learning Analytics (LA) has the potential to be used as a unique and viable learning, teaching and research

tool to analyze data from longitudinal assessment. The online language assessment platform, Profil

Linguistique, is an innovative and useful tool, in that (1) it adapts to students learning abilities and progress

and gives them the chance to monitor their progress, (2) it uses data mining to provide reports to teachers

and administration who subsequently adapt the general language program in a Canadian university. From a

theoretical point of view, the testing construct identified as the basis of this online assessment tool would

engage students in progressing in their language competence in parallel with the courses they are taking. It

is a provocative and unique way to integrate and look at assessment as a teaching tool by using LA.

1 INTRODUCTION

Educational applications of data mining and learning

analytics are a growing trend in higher education

due to the vast amounts of data becoming available

from the growing number of uses within e-learning

environments (ElAtia and Ipperciel 2015; Zaiane

and Yacef 2015; Bakhshinategh et al. 2018).

Learning analytics (LA) is data analytics in the

context of learning and education. It involves

collecting data about learners ‘activities and

behaviours, as well as educational environments and

contexts, and using statistics and data mining

techniques to extract relevant patterns that reveal

how learning took place. According to Diaz and

Brown (2012), LA is the “use of data, statistical

analysis, and explanatory and predictive models to

gain insights and act on complex issues (…) about

the learners (3).” LA can be used to report measures

and patterns related to learning activities, or to

optimize learning activities and strategies and/or

learning environments. Two types of data can be

used for implementing LA. First, data generated by

hte learners themselves, and often referred to as

digital footprints. This type of data would enable us

*Dr. ElAtia is the principal investigator on this project and

is the contact person.

to implement techniques to carry out data mining

analyses leading to a holistic understanding of

students’ behaviour. Second, data supplied by

learners in the form of surveys and other

demographic and background information. This data

provides a foundation for building an information

system about students. Both types of data are

necessary to learn about how learners react, behave,

interact and use a specific e-learning environment.

LA also provides (1) insights on how effective are

such environments and (2) feedback for both future

improvement and potential wider use. In this

research project, we are using LA to empirically

study students data collected from an on-line

interactive assessment framework that targets

language competence. The objectives of LA can be

to report measures and patterns related to learning

activities, or to optimize learning activities and

strategies and/or learning environments.

For the last two years, a research team at the

University of Alberta worked on developing an

assessment model within an e-learning environment

that comprise of individualized diagnostic, formative

and summative evaluation modules using “Moodle”

as an e-delivery platform and the Canadian

Language Benchmarks as competence indicators.

This assessment model, named ‘profil linguistique

(PL)’ provides a learner-centered and an integrated

674

ElAtia, S. and David, E.

Using Learning Analytics within an e-Assessment Platform for a TransFormative Evaluation in Bilingual Contexts.

DOI: 10.5220/0007860406740680

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2019), pages 674-680

ISBN: 978-989-758-367-4

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

approach to students own evaluation of language

achievement and is meant to supplement content-

based courses. The PL allows us to offer a language

program anchored in a continuous contact with the

language (Berman and ElAtia 2008) within content-

based courses (ElAtia 2011, ElAtia and Lemaire

2013) and which takes into consideration learners

strategies, motivation, constructive feedback and

self-engagement within the theories of language

acquisition, (Cohen 2012, 2011, 2010). The premise

is that by taking their language learning in-hand in

the PL, students will have a holistic idea of their

progress and most importantly would identify their

linguistic weaknesses and elaborate personal

strategies for linguistic improvement. From a

research perspective, data produced and collected

from the PL constitutes a solid foundation for

carrying LA studies that will bring new insights into

understanding how students interact with various

learning materials within bilingual e-learning

environments. We hope to improve our

understanding of the strategies used by students to

solve problems, to correct mistakes and to

circumvent difficulties. Within an LA framework,

the objectives of this research are to:

(a) Understand what helps students succeed when

using this independent e-learning model; how to

use analytics to improve the design and

applicability of each parts in the PL in such

ways as to promote student success in engaging

in their own language learning, be it French or

English;

(b) Use data to understand the various subgroups

within the students’ population; to build a

comprehensive behavioral pattern for practical

direct input into regular classes.

(c) Develop specific data mining techniques to

extract, sort, store, cluster and analyze data,

determine patterns to seek from the data, and

maximize what is available to support students,

teachers and administration.

2 BILINGUAL ASSESSMENT AND

ENGAGMENT

2.1 Context of the Study

The Official Languages Act went into effect in 1969,

giving French and English equal official status

within Canada. Bilingualism has since been

promoted not only at the federal level and the

working of government but also provincially

through the French immersion language programs.

However, outside of certain centers, namely Quebec

and New Brunswick, French is in a minority context

within an English-dominant environment. The

competence in French in the English speaking part

of Canada is heavily influenced by several factors as

shown in figure 1. The language identity plays a big

part in the language development of students across

Canada.

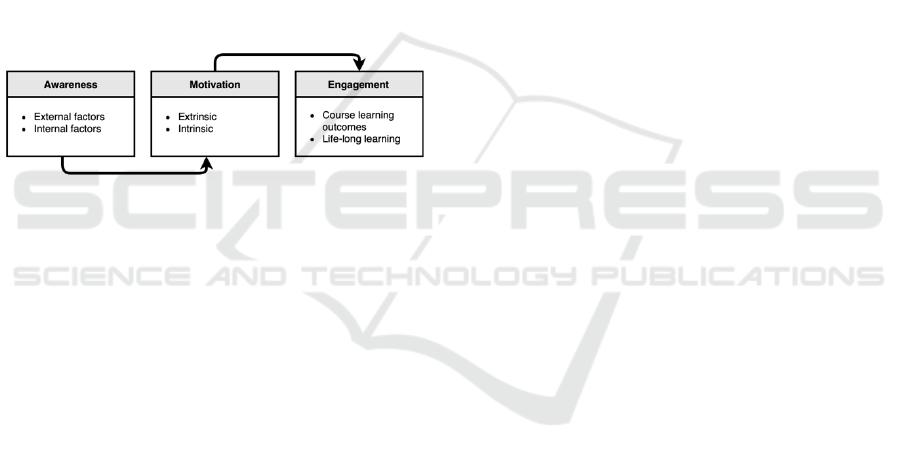

Figure 1: Elements Impacting Language in Canada.

While French Immersion programs are common

across Canada, students wanting to carry out their

higher education choose to do so amongst a very few

bilingual programs and institutions such as Glendon

College at the York University and Campus Saint-

Jean at the University of Alberta. However, within

these bilingual programs, mastering the two official

languages is a requirement for admission and

students are faced with the challenge of having to

work on their second /other language (either French

or English) in order to graduate with the required

language competency. Program administrators face a

challenge in this situation because there is little

space within the majority of a 4 year program to add

language courses. The profile linguistique (PL) was

conceived as a testing and teaching tool that can be

carried out by students and support staff outside of

class time, and monitored by teachers and

administrators to offer a language support

opportunity to students in parallel to their content-

based course work. Assessment, in all its facets from

diagnostic, formative and summative, is used to

motivate and engage the learners.

Students in these bilingual programs face few

challenges that we hope the PL address:

linguistic heterogeneity

heavy content base coursework

language competence plateau

This study took place in a large university in

Western Canada, within its bilingual campus,

located within an English dominant environment,

and consequently, the students are in a francophone

linguistic minority context within an historical

French minority. Upon acceptance to university,

students take an online French and English

Using Learning Analytics within an e-Assessment Platform for a TransFormative Evaluation in Bilingual Contexts

675

placement test in order to identify their proficiency

level and to place in the appropriate class. The

purpose of PL is going beyond a placement test: it

aims to create an online platform that would allow

for in individualized language learning experience

using LA outside of classrooms.

2.2 Assessment for Language Learning

Assessment is generally an applied research field

that interconnects (a) learning styles and

preferences, (b) teaching strategies, and (b)

evaluation techniques. Assessment can serve both

learning and teaching; in fact, assessment can be a

powerful tool where assessment becomes a platform

in service of learning. Formative assessment can be

used as a tool to advance learning where students

take their learning into their own hands. Students’

performance exceeds expectations once they are

engage.

Figure 2: TransFormative Triangulation.

The PL is anchored in a transformative assessment

framework (Popham 2007), where the emphasis in

on evidence-based assessment and understandings of

students’ language progress from three primary

stakeholders: students, instructors and program

administrators. The purpose is not only to do a

survey, gather information, and establish a starting

point about students’ progress, but also to create a

loop of constructive feedback and assessment that all

stakeholders can use to improve and change learning

patterns throughout a two-year cycle. Figure 2

summarises the theoretical basis for the PL: from

raising awareness, to motivating students do better,

to finally an engagement on their part to learn.

As a first step, it is rudimentary to establish a

baseline for learning; we are then positioned to

determine progress against this baseline and provide

evidence of development (Astin, 1985, 1991; Banta

and Palomba, 2015). Importantly, assessment can

thus become a platform in the service of learning.

This is captured in the diagnostic assessment phase,

which contains both a detailed survey and a

competence test. The second, and substantive phase,

is the formative part of the Pl, that contains 5

modules, each containing a series of assessment

tools. Formative evaluation can be used as a tool to

advance learning, with its focus on students taking

on responsibility for their own learning (ElAtia and

Lemaire 2013). Indeed, evidence supports that

students’ performance exceeds expectations once

they are engaged in their learning (Kuh 2009;

Berman and ElAtia 2008). Teachers, on the other

hand, can change their pedagogical approaches to

address students’ needs, based on the feedback they

receive from students (Popham 2007, 2011). During

a learning process, consciously being aware and

actively engaged in the progress of learning has

proved central to learners fully endorsing the

objectives and outcomes they are exposed to in a

course (Harperand Quaye 2009; Schmidt 1990, Ellis

2008). Building on this principle of engaged

learning (versus more static, passive learning),

instructors and administrators clearly must draw

students’ attention to the details of the learning

process itself—and continual formative assessment

certainly aids this. The PL serves this purpose by

explicitly focusing on the student as an active part of

the learning process, it is a tool that can help

students awaken to awareness, thus facilitating

engagement. As students do the assessment, they

become aware of their progress; whether for

extrinsic or intrinsic purposes, they will be

motivated to improve their standing; and by doing

so, they will become more engaged and reflective of

their own learning, be it at the course level or at the

extracurricular one. Astin (1984, 1993) in

conjunction with Lawon et al (2012) and Lyster

(2010) insist on the effectiveness of pedagogical

techniques that learners would not otherwise use,

were they not centered on heightening awareness of

the learning process. In turn, this leads to motivation

to improve the implementation and learning the PL

provides an independent, non-intimidating, self-

monitoring platform that generates visual reports

(securely and confidentially) that users can build on

for a more engaged learning/teaching of languages

within an academic program. The assessment within

PL demarcates itself from other tools by allowing

users to (1) visually track progress, (2) pinpoint

acquired/not yet acquired attributes, and (3) build a

portfolio of artifacts as evidence of acquisition.

2.2.1 Canadian Language Benchmarks

Know in French as the Niveaux de compétences

langagiers canadiens are the national standards in

English and French for describing, measuring and

recognizing second language proficiency of adults in

Canada. They are founded on models of

A2E 2019 - Special Session on Analytics in Educational Environments

676

communicative competence; they are descriptive

scales of language ability both (ESL and FSL). The

Benchmarks are written on a 12 scale reference pints

along a continuum from basic to advanced

proficiency. These 12 benchmarks reflect

progression of the knowledge and skills that underlie

basic, intermediate and advanced ability among

adult ESL and FSL learners. Because they are a

Canadian products, that has been developed while

taking in consideration the cultural, social,

economic, political consideration in Canada, we

used them as our point of reference for developing

the content materials for the PL. The benchmarks are

also used by various employers in requiring special

French or English language competence. For the PL,

we created modules and various testing tools that

target level 5 to 9of the benchmarks; we did not take

into consideration level 10 to 12 because they relate

more to graduate education than to the

undergraduate one.

2.3 Description of the

Profil Linquisitique

This triangulation model was used during a year-

long formative assessment model where learning

analytics and educational data mining were

implemented to single our elements within students’

profiles that could predict their success. The online

platform of the PL was created in 2012 using

Moodle as the learning management systems; as

dynamic and computer adaptive platform with a data

collection model for process mining. The PL is a

bilingual comprehensive online assessment portal

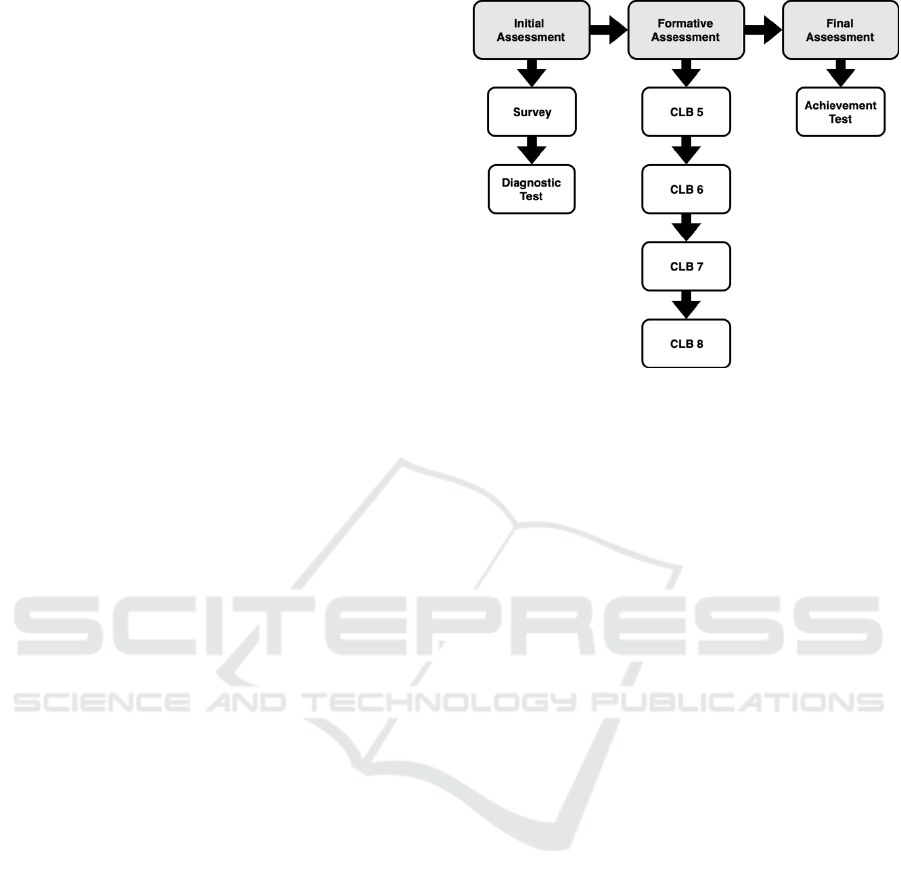

that has three components as shown in figure 3

below:

1. The initial assessment phase contains (1) an

extensive survey about the language background of

the students and (2) a diagnostic test that serve to

identify the competence of the students both in

English and French.

2. The formative assessment phase contains five

modules calibrated with the Canadian Language

Benchmarks (CLB). Each module contains various

quizzes and tests that students can independently use

outside of class to target specific learning objectives

they want to improve for either French or English.

3. The achievement phase contains a high stakes

competency test of language for academic purposes

and for specific purposes such as business and

nursing.

Figure 3: Components of the Profil Linguistique.

3 ONLINE ASSESSMENT

PLATFORM

3.1 Learning Management System

The university where the study is undertaken, uses

Moodle as its learning platform. Moodle is designed

to provide educators, administrators and learners

with a single robust, secure and integrated system to

create personalised learning environments. It is an

open source product, meaning that the source code is

openly available and that there is an entire

community of people contributing to the

improvement of the project – whether it be by fixing

bugs or creating new modules. eClass, powered by

Moodle, is the university’s centrally supported

learning management system. eClass houses the

university’s credit and non-credit courses. To access

these courses, users must (1) have a Campus

Computing ID (CCID) account and (2) be enrolled

in these courses. CCID accounts are created mainly

for university students within a few days after their

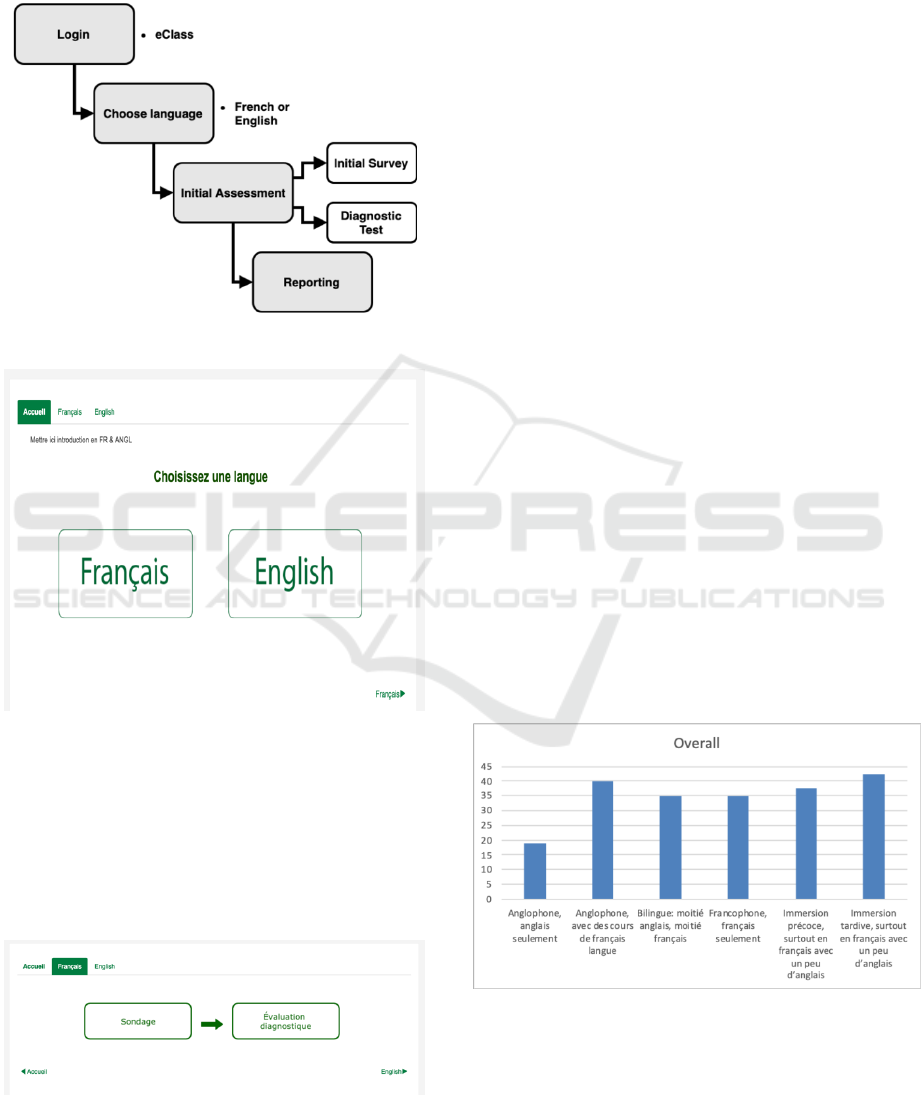

application. Figures 4, 5 and 6 show the progress of

the within the PL.

Even though PL is an assessment tool, it is

developed in eClass as a private non-credit course

and used to evaluate upcoming students. For the

purpose of generating data, we have made students

that are currently enrolled in language courses at the

university as PL’s participants for the duration of

this research. These students are enrolled and

grouped by their own cohorts at the course-level;

thus allowing teachers to monitor the progress of the

students and provide input and feedback on the

Using Learning Analytics within an e-Assessment Platform for a TransFormative Evaluation in Bilingual Contexts

677

content of the assessment modules. Upon entering

the course, students can choose between French and

English ‒ whichever language they are assigned to

be assessed in.

Figure 4: Gradual Progress in the PL.

Figure 5: Initial Log in screen.

Once in their learning space, students can choose the

language of their choice for the assessment. They

have the option to work on either language

depending on their preferences and language needs,

i.e. francophone tend to work on English more, and

the English speakers tend to work on their French

more.

Figure 6: The Diagnostic Assessment Phase.

The screenshots in figure 5 and 6 above describe the

first steps in the diagnostic assessment. The survey

is mandatory before the test. A part from the written

production that would need to be graded by teachers,

students, upon completing their assessment, receive

a table of their work broken down by item. The

administration gets a different aggregate report that

would allow it to advise students on future task to

undertake to improve language production.

4 INITIAL DATA RESULTS

To analyze data, we used (1) Python, a programming

language popularly used in data science, (2) Pandas,

a Python data analysis library, and (3) Microsoft

Excel to produce graphs. In eClass, we downloaded

the data from the survey and DA in CSV file format.

To generate reports, the participants are de-identified

and instead, have been assigned a random unique

ID.

Concurrently, we carried analyses using the

survey as our first point of reference to understand

how students navigate through the various

assessment modules in the PL, their answers and

feedback, to investigate clusters, identify outliers,

and map out rule associations that would shed light

on how the various groups and subgroups students

interact within e-assessment models.

The focus of this article is the initial phase.

Using the survey and the diagnostic assessment, we

were able to identify unique trends that would

explain students’ behaviour while interacting with

the language diagnostic tests.

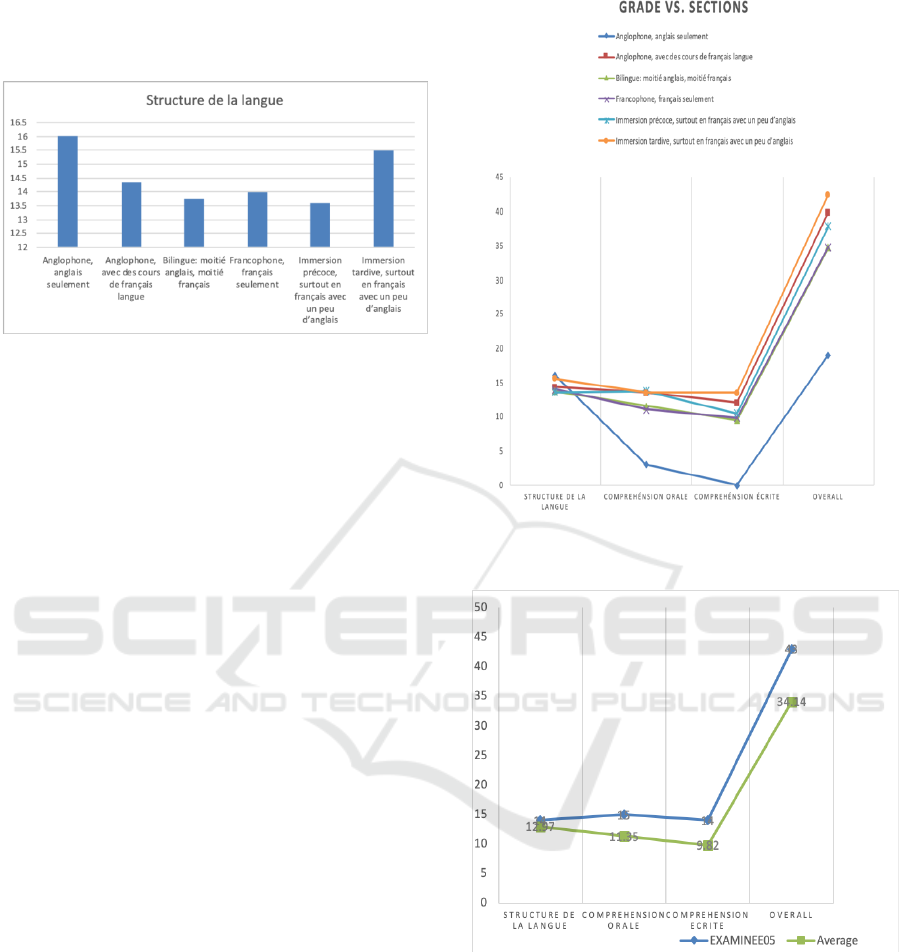

The figures below show how we were able to

Figure 7: Overall Performance by Type of background

Education.

In Figure 7 above and Figure 8 below, we look at

the performance by type of prior education program

in the elementary and secondary level. The cluster

A2E 2019 - Special Session on Analytics in Educational Environments

678

analysis shows that the previous language of

instruction of students does in fact predict their

competence in various parts of the PL.

Figure 8: Partial Performance by Type of background

Education.

The type of education that students had before

joining this program has an impact on their language

competence. Their performance in the test clearly

can be clearly predicted by which program they

attended. Moreover, performance in particular parts

in the diagnostic test can we traced to their

background education. By doing do, the PL can help

us identify trends among certain groups; and

consequently, be able to adapt the teaching material

and to target specific component of language

acquisition that each group needs to work on, or

strengthen. Such reports will help the administration

identify where resources should be allocated in order

to help students in the program attain the adequate

degree of language competence.

In graphs 9 and 10, we delved into specific parts

of the diagnostic test. The purpose was to be able to

generate reports for individual examinees. Both

graphs show the performance broken by parts.

Students will be able to find out which of the

language component they master, and which one

still need some work. By comparing each student to

the mean, they can visualise their progress, become

aware of their current language status with the hope

to motivate them to do better and seek help from the

various resources that are available to them in their

programs. They can then pursue the formative

modules within the PL.

Overall, the initial results showed us various

clustering and trends that we were unsuspecting of.

It helps us revise the theory of immersion students

vs. the French as second language students.

Figure 9: Overall Performance within the 4 Parts of the

Diagnostic Test.

Figure 10: A Comparative Visual of one subject with the

Group.

5 CONCLUSIONS

We aim to build an LA model that would allow us to

carry in-house research that would benefit students,

the university and academic communities. This is

the first round of analysis that we carry on the PL.

We realise that one of the drawbacks is the small

pool of examinees. However, we are confident as

Using Learning Analytics within an e-Assessment Platform for a TransFormative Evaluation in Bilingual Contexts

679

more students are using the PL, we will accumulate

data that will help us understand behaviour,

performance and needs of our students.

This project will open new doors for improving

our understanding of students’ interaction within e-

learning models specific to language competence.

As a result, we will, longitudinally and

comprehensively, be able to explore data relating to

students. The development of a data warehouse

model and data mining algorithm for the LA model

will have utility for secondary and post-secondary

language programs across Canada. Using this

complete assessment framework and the ensuing LA

model, both the substantive and the qualitative

results, will allow program teachers and

administrators to holistically follow students’

progress throughout their academic careers and to

customize their programs for optimal success. Our

initial data and analysis does support our thesis and

we plan to carry out more extensive analysis as more

robust data is collected.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research has been possible from the Provost

office from the McCalla Professorship, awarded to

Dr. ElAtia in 2017-2018

REFERENCES

Astin, A. (1985). Achieving Educational Excellence: A

critical Assessment of Priorities and Practices in

Higher Education. San Francisco, CA : Jossey-Bass.

Astin, A. and Antonio, A.L. (1993). Assessment for

Excellence: The Philosophy and Practice of

Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education.

Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers

Banta, T.W. and Palomba, C.A (2015). Assessment

Essentials: Planning, Implementing, and Improving

Assessment in Higher Education. San Fransisco. CA:

Jossey-Bass

Bakhshinategh, B., Zaiane, O.R., ElAtia, S. and Ipperciel,

D. (2017). Educational data mining applications and

tasks: A survey of the last 10 years. Education and

Information Technologies, 22(4), 1–17.

Berman , R and ElAtia, S. (2008). Classroom time as a

factor in instruction of English for academic purposes.

In Z. Ibrahim et S. Makhlouf (eds.). Linguistics in an

Age of Globalization. Cairo: AUC Press, 131-145.

Cohen, A.D. (2012). Strategies: The interface of styles,

strategies, and motivation on tasks. In S. Mercer, S.

Ryan, and M. Williams (Eds.), Language learning

psychology: Research, theory, and pedagogy (136-

150). Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cohen, A.D. (2011). Strategies in learning and using a

second language. Harlow, England: Longman Applied

Linguistics/Pearson Education.

Cohen, A.D. (2010). Focus on the language learner:

Styles, strategies and motivation. In N. Schmitt

(Ed.), An Introduction to Applied Linguistics (161-

178). 2nd ed. London: Hodder Education.

Diaz, V. and Brown, M. (2012). Educause Learning

Initiative: Learning Analytics. Retrieved from:

http://www.educause.edu/ELI124

ElAtia, S. (2011). Enhancing Foreign Language Writing in

Content-Based courses. Journal of Theory and

Practice in Education, 7, 2: 192-206.

ElAtia, S. and Ipperciel, D. (2015). At the Intersection of

Computer Sciences and Online Education:

Fundamental Consideration in MOOCs Education.

Educational Letter, 11 (2), 2 – 7.

ElAtia, S and E. Lemaire. (2013). Engager les apprenants

dans l’autocorrection de leurs productions écrites : le

cas du portfolio d’erreurs. The Canadian Journal of

Applied Linguistics. 16,1: 111-134.

Ellis, R. (2008). The study of second language acquisition.

Oxford, UK : Oxford University Press.

Harper, S.R. and Quaye, S.J. (2009). Student Engagement

in Higher Education. New York and London:

Routledge.

Kuh, G. (2009), Organizational culture and student

persistence: Prospects and puzzles. Journal of College

Student Retention, 3(1) 23-9.

Lawson, R., Taylor, T., Herbert, J., Fallshaw, E., French,

E., Hall, C., Kinash, S., and Summers, J. (2012, July).

Strategies to Engage Academics in Assuring Graduate

Attributes. Paper presented at the Eighth International

Conference on Education, Samos, Greece. Retrieved

on June 5, 2018, from http://

eprints.qut.edu.au/52630/2/52630.pdf

Lyster, R. et Ranta, L. (1997). Corrective feedback and

learner uptake: Negotiation of form in communicative

classrooms. Studies in Second Language Acquisition,

19, 37-66.

Popham. J. (2008). Transformative Assessment.

Alexandria: VA: Association for Supervision and

Curriculum Development.

Schmidt, R. (1990). The role of consciousness in second

language learning. Applied

Linguistics, 11, 129-158.

Zaiane, O.R. and Yacef, K. (2015). MOOCs are not

MOOCs Yet: Requirements for a True MOOC or

MOOC 2.0. Educational Letter, 11 (2), 17 – 21.

A2E 2019 - Special Session on Analytics in Educational Environments

680