Requirements for an In-gallery Social Interpretation Platform:

A Museum Perspective

Marcus Winter

a

School of Computing, Engineering and Mathematics, University of Brighton, U.K.

Keywords: Museum, Visitor Interpretation, Social Interpretation, Informal Learning, Participation, Engagement,

User-generated Content, Content Moderation, Content Ownership.

Abstract: This paper reports findings from expert interviews discussing in-gallery commenting systems with museum

professionals. Its main contribution is an exploration of museum perspectives on critical aspects of

commenting platforms including content moderation, comment metadata, access and openness, ownership

and reuse of comments, backend requirements, deployment and maintenance. The paper relates findings to

system requirements and flags up a number of design tensions between visitors' attention to exhibits and their

engagement with interpretive resources; visitors' communication behaviours and their contemplative needs;

museums' requirements for content moderation and visitors' user experience when submitting comments. The

findings will be useful to researchers and practitioners developing in-gallery commenting systems and other

platforms collecting and displaying visitor comments in museums.

1 INTRODUCTION

The idea of museums as places for informal learning

has been around for some time and is now ubiquitous

in the literature. Screven (1969) understands

museums as "responsive learning environments"

(p.10); Hein (1998) writes about the "constructivist

museum" (p.155); Bradburne (2000) studies

museums as "support systems" for informal learning

(p.19); Falk and Dierking (2000) call exhibitions

"design-rich educational experiences" (p.139) and

discuss museums as places for "meaning-making",

and Forrest (2013) calls exhibitions "interpretive

environments" (p.201).

Common to all these views on museums as

learning environments is a grounding in social-

constructivist (Bruner, 1973; Bandura, 1977;

Vygotsky, 1978) and experiential (Kolb, 1984)

theories of learning, where visitors encounter learning

opportunities and actively construct knowledge by

making connections, solving problems, discussing

meaning with others and reflecting on their

experience. A key requirement for this type of

learning is that visitors interact with exhibits and

engage in conversations - a "primary mechanism of

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6603-325X

knowledge construction and distributed meaning-

making" (Falk and Dierking, 2000; p.110).

In order to support this distributed meaning

making, museums use various platforms enabling

visitors to share their views on exhibits, exhibition

themes and their visiting experience. These range

from traditional analogue mechanisms such as visitor

books, comment cards and Post-it® walls to digital

platforms such as interactive screens, museum

websites and social media platforms. Visitors

typically have clear favourites among these

mechanisms, based on their specific affordances in

relation to abstract qualities such as ease of use,

freedom of expression, range of functionality, fit with

personal communication preferences, privacy and

expected impact when contributing a comment

(Winter, 2018). From a museum perspective,

important criteria for commenting systems include

how they support their pedagogical needs, how they

integrate with professional practice and workflows,

how affordable they are and how they fit with the

design and technical constraints of the gallery space.

The context of this paper is an effort to extend the

current range of commenting mechanisms with the

development of Social Object Labels (SOLs); an in-

gallery commenting system aiming to foster debate

66

Winter, M.

Requirements for an In-gallery Social Interpretation Platform: A Museum Perspective.

DOI: 10.5220/0008354400660077

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications (CHIRA 2019), pages 66-77

ISBN: 978-989-758-376-6

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

around exhibits and complement the museum's voice

displayed on traditional object labels by enabling

visitors to share their own commentary on small,

interactive, e-ink screens (Winter, 2014; Winter et al.

2015). SOLs aim to support a particular pedagogical

approach to social learning in museums based on the

idea of object-centred sociality, which proposes that

people find it easier to engage with each other around

objects of common interest than to engage directly

without such points of reference (Knorr-Cetina, 1997;

Engeström, 2005; Simon, 2010).

This paper reports on a series of expert interviews

discussing commenting in general and in-gallery

commenting systems in particular with museum

professionals. It complements a survey exploring

visitors' views on commenting in museums (Winter,

2018) and forms part of a wider requirements analysis

informing the design of SOLs. The main contribution

of this paper is an exploration of museum

perspectives on commenting in museums, covering

content moderation, comment metadata, access and

openness, ownership and reuse of comments,

backend requirements, deployment and maintenance.

As these aspects are not specific to SOLs but relevant

to any platform collecting and displaying visitor

comments in museums, it is hoped that the findings

are of interest to practitioners and other researchers in

this field.

The following sections briefly review related

literature before reporting on a series of interviews

conducted with museum professionals, explaining the

methodology of the study and discussing its findings

in the context of high-level requirements that can

inform the design of commenting platforms from a

museum perspective. The paper concludes with a

summary of findings, a discussion of limitations and

an outlook on future research.

2 BACKGROUND

As curated spaces with an educational agenda and

particular social protocols, museums are complex

environments with their own set of requirements and

constraints. This section investigates how

commenting fits with museums' higher-level

educational goals, discusses engagement, interaction

and technology use in gallery environments and looks

at existing curatorial practices to encourage visitor

engagement with exhibits. It also reviews previous

research efforts in the literature exploring

technologies for visitors to comment on museum

exhibits and discusses user-generated content in the

contexts of authority and public liability.

2.1 Giving Visitors a Voice

Bradburne (2002) conceptualises interactivity not as

a property of the exhibit but of the visitor, and

introduces the notion of "user language" as a way for

museums to shape visitors' engagement with exhibits.

As the museum's user language confers properties on

both the exhibit and the visitor, it structures their

relationship and controls whether interaction takes

place and of what nature it is. Bradburne (ibid)

identifies the most common user languages in

museums as (1) authority, where visitors accept the

museum as authority, (2) observation, where visitors

are their own authority, (3) variables, where visitors

explore relationships between exhibits, (4) problems,

where visitors analyse problems and (5) games,

which extends problem and makes action a condition

of the experience. Commenting fits well with the user

languages of observation, variables and problems, for

instance when posing a question for visitors to

answer, however, its intrinsic qualities of allowing

visitors to express their own views, share them with

other visitors and make them part of the exhibition

add another dimension, which might be called the

user language of voice.

The user language of voice confers on museums

the property of being interested in visitors as thinking

beings (Adams and Stein, 2004), on exhibits the

property of being open to interpretation rather than

fully described and interpreted, and on visitors the

property of having a voice to engage in public debate

and balance the museum's authoritative

interpretation.

It expands the range of user languages available

to museums and acknowledges that visitors do not

come as blank slates to the museum but with a wealth

of previously acquired knowledge, interests, beliefs

and experiences (Falk and Dierking, 2000). Giving

visitors an opportunity to provide their own

interpretation and relate concepts and ideas behind

exhibits to their personal experiences can help them

to "see themselves within an exhibition" (ibid, p.182),

addressing the problem that many visitors cannot

relate to exhibits based on the information given on

object labels (Screven 1992).

2.2 Learning from Label Design

Vom Lehn and Heath (2003) point out that

interpretive labels were not always part of the

museum experience but only introduced when

museums became educational institutions and guided

tours gave way to visitors navigating exhibitions on

their own. Today, interpretive labels are a standard

Requirements for an In-gallery Social Interpretation Platform: A Museum Perspective

67

tool for museums to bridge the knowledge gap

between visitors and objects (Loomis, 1983). Their

manifold purposes include to provide information

about exhibits, orient and instruct visitors, personalise

topics and interpret exhibits (Screven, 1992).

SOLs are in many ways the antithesis of

interpretive labels - championing the visitor voice

rather than the museum voice, affording many-to-

many communication rather than one-way top-down

communication and showing unverified, potentially

biased or trivial information by visitors rather than

authoritative information by the museum. Yet, there

are also similarities in that both visitor comments and

interpretive labels should be noticeable but not

compete with exhibits for visitors' attention (Bitgood,

1996), creating a particular design challenge.

Screven (1992) proposes that visitors' decisions to

engage with interpretive labels depend on their

perceived value-to-cost ratio, and he offers

recommendations to maximise value and minimise

costs. Bitgood (1996) contends that attention is

selective, involves focusing power and is of limited

capacity. He structures design aspects around (1)

stimulus salience and traffic flow with regard to

attracting visitors' selective attention, (2) minimising

distractions and perceived effort while increasing

cognitive-emotional arousal with regard to

motivating visitors to focus, and (3) taking into

account contextual factors to explain museum

visitors' decreasing capacity of attention over the

course of their visit. Both sets of recommendations

incorporate a deep understanding of museum visitors

and gallery environments and are highly relevant to

the design of commenting systems.

2.3 Museums as Curated

Environments

Falk and Dierking's (2000) statement that "people go

to museums to see and experience real objects, placed

within appropriate environments" (p.139) hints at two

key aspects that make the museum experience

special. One refers to being in the presence of

authentic objects rather than replicas and the other to

being in a curated environment specifically designed

to heighten the experience with these objects. Latham

(2013) uses the term "numinous experiences" to

describe the phenomenon of visitors being awestruck,

reverential and deeply moved when encountering

authentic objects in museums. She contends that

regardless of emerging technological trends the

authentic physical object is an important aspect of the

visitor experience and central to the act of meaning-

making.

Tröndle and Wintzerith (2012) discuss the

etymological meaning of "museum" as "art temple"

and point out that it has contemplative undertones as

opposed to the modern conception as a place where

visitors socialise and want to be engaged. They quote

19th century art writer Quatremère de Quince

complaining about "the conversation-addicted

masses" and 20th century art critic Arthur Danto

lamenting about the "Disneyfication" of museums.

Research suggests that these misgivings are not

unfounded: Tröndle and Wintzerith (2012) found that

visitors who converse in exhibitions are less affected

by displayed artworks than visitors who don't

converse and focus on the exhibits; Henkel (2013)

found that visitors who take pictures of artworks

remember less details of them than visitors who just

look at the artworks; vom Lehn and Heath (2003)

found that visitors using mobile phones as

interpretation tools tend to focus on the device screen

rather than the exhibit. As a consequence, "many

curators and museum managers are concerned that

these new technologies may not only undermine the

aesthetic of the gallery but provide resources that

distract from, or even displace, the object" (ibid, p.3).

In order to reconcile visitors' communicative

needs with their contemplative requirements, Tröndle

and Wintzerith (2012) suggest that museums must

carefully manage an economy of attention, ensuring

that visits can be an aesthetic event as well as a social

experience. These views are echoed by vom Lehn and

Heath (2003), who call on developers of interpretive

resources to "preserve the primacy of the object and

aesthetic encounter" (p.3), and by Maye et al. (2014)

who report cultural heritage professionals stressing

"the need to use technology in ways that do not

distract from the exhibition themes" (p.601).

2.4 Social Object Interpretation

Referencing Engeström's (2005) observation that

discussions on social networks typically develop

around objects such as photos, jobs or shared

interests, Simon (2010) describes how visitors tend to

engage with each other around social objects in

museums. However, while designers of Web-based

experiences have a wide range of well-researched

mechanisms and tools at their disposal to support

object centred sociality and user generated content,

curators of physical exhibitions typically rely on

traditional commenting systems like visitor books

and feedback boards to foster discussions around

exhibits, which do not integrate with visitors' digital

communication habits.

CHIRA 2019 - 3rd International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

68

Technologies supporting visitors' social

interpretation of exhibits are rare, although there have

been several research efforts. Stevens and Toro-

Martell (2003) present VideoTraces and ArtTraces, a

kiosk based system enabling museum visitors to

select or create images or videos of exhibits or their

interaction with them, and to annotate them with

speech or gestures. As these 'traces' can be shared

with other visitors to communicate interpretations,

explanations and questions, the system fosters

engagement and social-constructivist learning.

Van Loon et al. (2006) discuss ARCHIE, a

handheld game-based interactive museum guide

drawing on Falk and Dierking's (2000) contextual

model of learning, which proposes that visitors'

interaction and learning in museums are influenced

by overlapping personal-, physical- and the socio-

cultural contexts. Reflecting these ideas, the system

involves visitors in collaborative games and

stimulates interaction and communication between

them around museum exhibits.

Hsu and Liao (2011) describe a mobile

application integrating self-guided exploration of an

exhibition with social object annotation. The system

enables visitors to share their views about exhibits by

scanning a RFID tag with their mobile device and

adding their personal commentary. Similarly, the

QRator (Gray et al., 2012) and Social Interpretation

(Bagnal et al., 2013) projects, both based on a

common precursor project Tales of Things (Barthel et

al., 2010), enable visitors to scan visual or radio-

frequency codes attached to exhibits and share their

personal commentary. While all these efforts have

fundamental usability problems related to the

discoverability of digital annotations (Winter, 2014),

they support social-constructivist learning in

museums in principle by providing a platform for

visitors to share and discuss their views about exhibits

and exhibition themes.

Girardeau et al., (2015) describe a location-based

system where visitors use their mobile phone to listen

to audio interpretations of both curators ("museum

voices") and other visitors ("community voices"), as

well as record their own audio comments in response

to prompts. By using visitors' location rather than

physical markers to identify and trigger content, and

by conceptualising the experience as an immersive

soundscape to explore and contribute to, the project

explores an attractive alternative way for museums to

give visitors a voice and foster their engagement and

learning.

These reports offer valuable guidance on how to

design, implement, frame and support social object

annotation in museums. They describe barriers to

participation, ranging from digital literacy and

technological issues to usability, learnability and

accessibility as well as the wider framing by the

organisation, and offer recommendations on how to

tackle these problems.

2.5 Authority and User-generated

Content

From a museum perspective, a key aspect of user-

generated content is quality, as wrong or

inappropriate comments not only impact on the

visitor experience but also undermine the

organisation's authority, which is a distinguishing

quality specifically for heritage organisations

(Oomen and Arroyo, 2011).

This creates a tension between visitors' user

experience when contributing comments and

museums' reluctance to yield control over content

displayed in their gallery space: On the one hand,

research indicates that visitors like to comment on

complex and controversial topics (Kelly, 2006), and

that they expect comments to be displayed

immediately after submission instead of being held in

a moderation queue (Gray et al., 2012). On the other

hand, there is a deep-seated fear among museum

professionals of visitors leaving wrong, inappropriate

or offensive comments that might reflect negatively

on the museum when displayed unchecked in the

gallery (Gray et al., 2012). Commenting systems

must therefore implement moderation mechanisms

that do not compromise the user experience while

enabling museum professionals to block or delete

wrong or inappropriate comments.

One approach to address this problem is discussed

by Stevens and Toro-Martell (2003), who suggest that

wrong or misleading comments should be addressed

by other visitors posting opposing views as well as

the museum directly responding to such content and

thereby demonstrating their expertise in a hands-on

manner rather than through distanced authority. With

respect to inappropriate or offensive comments, both

Russo (2008) and Gray et al. (2012) refer to Fichter's

(2006) concept of "radical trust", which accepts abuse

and vandalisms as being part of society but places

(radical) trust in the community and its members to

deal with these issues and safeguard continued

operation.

Moderation mechanisms implementing these

ideas typically combine community moderation to

monitor and flag wrong or inappropriate comments

with post-moderation by museum staff to scrutinise

flagged comments and eventually remove them, as

described for instance in Gray et al. (2012) and

Requirements for an In-gallery Social Interpretation Platform: A Museum Perspective

69

Bagnal et al., (2013). The advantage of this approach

is that it improves the user experience by allowing

content to be displayed instantly while also providing

a certain level of control and being operable with

limited resources.

2.6 Summary

The literature suggests that offering visitors an

opportunity to share their commentary around

exhibits and exhibition themes can foster engagement

and learning in the gallery space and help museums

towards their higher-level educational goals.

Commenting extends the range of "user languages"

(Bradburne, 2002) available to curators and can lead

to higher levels of participation by emphasising social

and communicative aspects of the museum

experience and signalling that museums value their

visitors' views.

Developers of in-gallery commenting platforms

can draw on a rich body of design guidelines for

interpretive labels, which reflect a deep

understanding of museum environments and are

highly relevant to both engaging visitors to contribute

comments and displaying visitor comments in the

gallery space.

They can also draw on previous research

designing, developing and deploying commenting

technologies in museums. Besides discussing

technical and design aspects, these studies give

insights into barriers to engagement and provide

recommendations how to overcome them.

Several authors point out that sociality and

technology in museums must be balanced with the

contemplative needs of visitors, stressing the

"primacy of the object" (vom Lehn and Heath, 2003)

and challenging developers of new applications to not

disturb the aesthetic experience in museums.

Regarding the quality of visitor-generated

content, research suggests that involving visitors in

monitoring and flagging inappropriate or offensive

comments strikes a good balance between response

time, editorial control and required resources.

Furthermore, museum staff openly opposing wrong

or misleading comments on the system can be an

effective way to assert their authority.

Overall, the literature supports the idea of

commenting as an effective way to support

participation and learning in museums, and offers

valuable insights that can inform the design of

commenting systems and their integration with

museum environments, while balancing visitors'

social and contemplative requirements and

maintaining museums' editorial control without

impacting on user experience.

3 METHODOLOGY

In order to explore a museum perspective on

commenting in museums, with a particular focus on

SOLs as an instance of an in-gallery commenting

system, seven in-depth interviews were carried out

with museum professionals from Science Gallery

Dublin, Regency Town House and Phoenix Gallery

Brighton. In order to cover a broad spectrum of views

concerning the design, deployment, maintenance and

integration of SOLs into existing practices and

workflows, interviewees with different

responsibilities were selected, with roles including

Technical Manager, Web & IT Manager, Programme

Manager, Marketing and Communications Manager,

Researcher, Director and Co-Chair. Interviewee

identifiers, used in the following sections to attribute

specific answers, together with their organisational

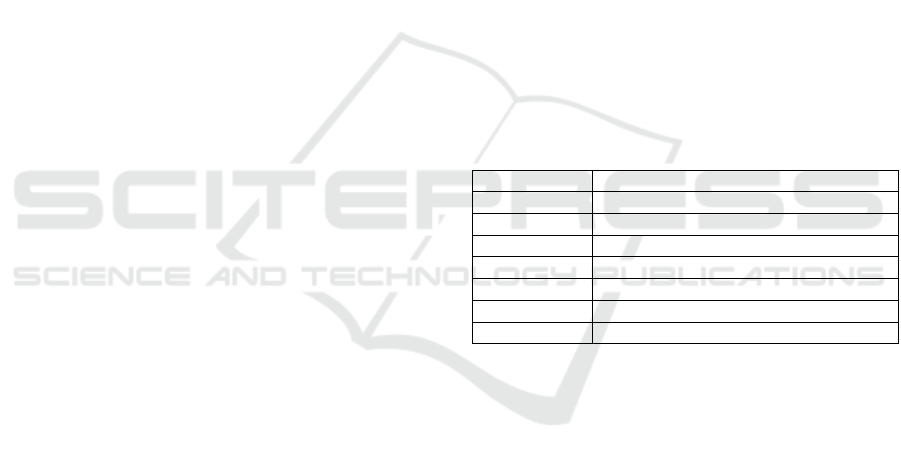

roles for context are listed in Table 1.

Table 1: Interviewee identifiers and their roles.

Interviewee Role in organisation

I1 Gallery Directo

r

I2 Pro

g

ramme Mana

g

e

r

I3 Researche

r

I4 Technical Mana

g

e

r

I5 Marketing and Communications Mg

r

I6 Web & IT Manage

r

I7 Co-Chai

r

The interviews were semi-structured, discussing a

fixed set of 15 starter questions relating to the

moderation (2), attribution (2), conservation and

reuse of content (3), openness of the system (2),

backend requirements (2), deployment aspects (3)

plus a final open question (1) inviting participants to

address any relevant points not covered in the

interview. Related aspects for each topic were further

explored with follow-up questions as they emerged

during the interviews.

The interviews were carried out by email (I1),

video link (I2, I3, I4, I5) and in person (I6, I7).

Interviews by video link and in person lasted between

32 and 54 minutes. Video interviews were recorded

and then transcribed, while interview answers in

person were captured through note-taking and

reviewed immediately afterwards to supplement and

clarify notes as recommended in Valenzuela and

Shrivastava (2008). The different data collection

methods necessarily led to differences in data

CHIRA 2019 - 3rd International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

70

granularity, with video transcriptions (4) yielding

richer data than both note-taking during interviews

(2) and email responses (1), however, all three

methods recorded participants' answers in sufficient

detail to be analysed as a single dataset for the

purpose of this study.

Answers from all interviews were aggregated

under their respective question headings and analysed

in a two-stage emergent coding process described in

Miles and Huberman (1994), involving first data

reduction and then a data visualisation. In the data

reduction stage, responses were read several times

and categorised according to key points in answers,

disregarding differences in data granularity and in

individual terminology and formulations. In the data

visualisation stage, the reduced and coded data was

structured after emerging themes for interpretation

and synthesis to summarise and qualify key findings.

Both raw data and annotated reduced data from the

emergent coding process were archived for further

analysis and scrutiny in the future.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Content Moderation

When asked the question "How should we deal with

inappropriate or offensive comments?", interviewees'

answers ranged from cautious and restrictive to

tolerant and open. For instance, one interviewee (I7)

pointed out that there is an issue with public liability.

As most galleries are publicly funded, they might

have an obligation to pre-moderate comments before

showing them in the gallery. However, as this

requires someone to do it, which in turn costs the

museum money, the same interviewee argued that

from this point of view post-moderation might also be

acceptable. Several interviewees questioned how

much of a problem inappropriate content actually

would be when running a commenting system in the

gallery space, with some participants pointing out that

visitors act more responsibly in the gallery space than

when online, and others arguing that offensive

content is "not the end of the world" (I4) as long as it

is removed in a reasonable time frame. The former is

supported to some extent by literature indicating that

museum visitors actually post less offensive content

in the gallery space than expected (Gray et al., 2012).

Against this backdrop, most interviewees spoke

out in favour of a post-moderation model, i.e.

moderating and removing inappropriate content after

it was made publicly available on the system,

supported by users flagging offensive content. A key

argument in favour of post-moderation was that it

requires fewer resources and offers a better user

experience as it eliminates the inevitable delay in pre-

moderation between posting a comment and it

becoming visible on the system. It was pointed out

that user-supported post-moderation follows best

practice on large social networks and discussion sites

on the Web and therefore should be familiar to most

users. Another argument in favour of post-moderation

was that it integrates well with current workflows in

museums, where staff keep an eye on the gallery

space and routinely check user-generated content

once or twice a day. This process can be supported by

users flagging up comments they find objectionable

and thereby directing moderators’ attention to

problematic content.

Rather than having a dedicated content moderator,

responsibility to react to user-flagged content is likely

to be distributed among a team of moderators on call.

In larger institutions this is likely to include technical,

IT and communications staff whereas in smaller

places this is likely to include the gallery manager and

volunteers. In order to shorten response times and

eliminate the need for moderators to repeatedly check

whether content was flagged, the system should

notify relevant staff when content is flagged. Ideally,

notifications should be delivered not only to staff's

desktop but also to their mobile device so that they

can react quickly even when not at their desk.

As suggested in particular by interviewees with IT

backgrounds (I4, I6), technical measures already used

on museum websites could be used to help avoid

inappropriate content being posted on the system.

These include automated screening of submitted

content to block spam and offensive posts and

logging IP addresses of contributors in order to be

able to block sustained abuse by specific users.

However, as both of these measures focus more on

spam and automated attacks than on offensive

content, they might be less relevant for content

generated in-situ and less effective for mobile devices

which are dynamically assigned a new IP address

each time they connect to a different mobile or WiFi

network.

4.2 Content Metadata

Content metadata associated with a comment, such as

the contributor's name, age, gender, etc. can play an

important role from both the contributor's and the

reader's point of view. From a contributor's

perspective, identifying marks such as a name or

username denote authorship and go some way to

acknowledge moral rights to the comment. From a

Requirements for an In-gallery Social Interpretation Platform: A Museum Perspective

71

reader's perspective, such metadata can potentially

help to contextualise comments by providing

background information about the author that might

explain their espoused views.

When asked whether comments should include

author-related metadata, none of the interviewees

brought up the aspect of establishing authorship and

moral rights of the contributor. Instead, answers

discussed the actual merits of metadata from a

reader's perspective and considered the user

experience of providing such data. With regard to the

former, it was pointed out that author-related

metadata often gives only “an illusion of context” (I2)

but in fact does little to help our understanding of a

statement and might possibly even hinder

interpretation by bringing into play prejudice based

on stereotypes, e.g. ageism. With regard to the latter,

most interviewees emphasised that entering

additional metadata should be optional and not a

barrier to submitting comments. It was also pointed

out that visitors should not feel that the institution is

collecting data about them as this might prevent them

from engaging, and that identifying markers (e.g.

name, age, where from) are expected only in certain

cultures but might not be seen as necessary or even

appropriate in others. Several interviewees suggested

that an optional name and the comment itself would

strike an appropriate balance between satisfying the

convention of identifying marks associated with a

comment and streamlining the user experience.

In digital systems, author-related metadata is

often drawn from user profiles and therefore closely

linked to logins and online identity. A second

interview question in this context was therefore

whether people should login in order to submit

comments. Interviewees broadly agreed that any

login should be optional and no barrier to

participation. Even third-party logins, which do not

require users to create an account on the system but

still uniquely identify them, were seen as problematic.

While they give instant access to a user’s profile

information and allow conversations to be easily

carried over to their social network, they exclude

people who do not use these services and might

alienate those who would rather not connect their

social network identity with their in-gallery

commenting.

4.3 Openness

From a visitor perspective, the openness of an in-

gallery commenting system is largely defined by the

degree to which it supports content export and import.

Users posting comments to the system might want to

be able to forward and reuse them on other platforms

and networks, e.g. their social network. Vice versa,

users might want to post comments relating to

exhibits while not present in the gallery space, e.g.

when they visit the museum’s website. The latter

opens up interesting use cases that mix in-situ and

remote commenting, but it also entails numerous

problematic issues ranging from content quality to

users’ conceptual models of the system.

When asked whether people should be able to post

their comments not only to the gallery system but also

to their social network, most interviewees agreed that

social media integration is generally welcome as it

might help drive traffic to the gallery’s website. Some

pointed out that this is how public discourse happens

these days and that most museums rely on social

media to engage audiences and disseminate news.

However, it was also pointed out that social network

integration could turn the process of commenting on

the gallery system into a relatively complex

interaction, and that some visitors might prefer to use

their default social network applications for this

process rather than built-in functionality in a custom

commenting application. Several interviewees

concluded that social network integration would be

nice to have but was not strictly necessary. One

interviewee (I4) suggested that propagation to social

media, specifically the museum's social media feed,

should happen automatically without requiring

additional user interaction.

The idea of remote content creation, where online

visitors are able to post comments to an in-gallery

system, received mixed responses from interviewees.

On the positive side, some interviewees pointed out

that it could help to bridge the gallery- and online-

experience of an exhibition, potentially leading to live

conversations between people on the website and in

the gallery. With suitable in-gallery notifications

when someone posts a comment online, this could be

exploited to stir interest and increase visitor

participation in the gallery space. Furthermore,

remote commenting would give repeat visitors, who

might develop an informed opinion on the subjects in

an exhibition, an opportunity to discuss them more in-

depth than would be possible with in-situ

commenting using a mobile device. On the negative

side, some interviewees warned that it might lead to

more spam and offensive content as people are less

inhibited online than in the gallery space. Overall

there might be limited returns from implementing

such functionality as people are more likely to

comment on their social network than on the

institution's website. Returning to the original idea of

an in-gallery commenting system, some interviewees

CHIRA 2019 - 3rd International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

72

emphasised that its purpose is to increase engagement

while visitors are physically in the space and that

commenting should therefore require visiting the

gallery and experiencing the work there. This view

was summed up in the statement that “A system

specialised on in-gallery commenting should not

dilute that purpose by trying to be a Swiss Army

Knife” (I6).

4.4 Content Ownership and Reuse

Ownership, storage and potential reuse of user-

generated content are important aspects from both

legal and motivational perspectives. Like any original

work, user-generated content is automatically

covered by copyright and has associated moral rights

(IPO, 2015). While attribution goes some way to

acknowledge authorship and moral rights, and

thereby to address motivational aspects of visitors

submitting comments, actual control over content can

lead to de-facto ownership. This aspect has been

pointed out by Benkler (2002) with regard to the co-

production of content and is supported by research

showing that many visitors link ownership of user-

generated content to ownership of the medium in

which content was submitted (Winter, 2018). The

same study also found considerable uncertainty and

variation among visitors' views on how museums

might store and reuse comments.

Concerning the storage and possible reuse of user-

generated content, some interviewees suggested that

comments should be archived together with

exhibitions and become part of their online

documentation. One interviewee (I7) suggested they

could even be stored on a small USB stick and

attached to the physical exhibit when archived. While

there were concerns as to how relevant archived

comments would be once an exhibition has ended,

some interviewees suggested that their main value

post-exhibition would be as a data source for

evaluation and reporting, especially as such data is

required when applying for funding. In this context

any data related to engagement and impact would be

useful, including analytics data from related web

sites.

Several interviewees pointed out that because they

could not anticipate how they might want to use

comments in the future they ideally should have a

license to reuse comments in whatever context and

format they think is suitable. With regard to touring

exhibitions, some interviewees suggested that

comments should travel with an exhibition while

others pointed out that they probably would not

because the exhibition would be presented as

something new and showing comments from a

previous instantiation would destroy that perception.

Some interviewees acknowledged that content

ownership and reuse are sensitive points and

suggested there should be a clear signal of intent on

the part of the institution to make it "crystal clear" (I2)

to visitors what is being done with their information.

In particular this should clarify if there are any plans

for commercial uses, for how long comments are

archived and who will have access to submitted

information, including whether comments are seen by

curators or given to the artist. The majority of

interviewees, however, were less concerned with

these issues and emphasised the need for lightweight

approaches. Suggestions in this line included having

a sign at the entrance, displaying a Creative

Commons logo in mobile applications, integrating an

unobtrusive notice into the visitor prompt and

generally doing only the “absolute minimum” (I4) so

as not to create a barrier to participation.

4.5 Backend Requirements

Backend requirements are based on functional needs

of institutions and users of the system. While some of

these have been discussed above (e.g. the requirement

to notify moderators when users flag comments), this

part of the interview focused specifically on content

moderation and syndication via an administration

interface (dashboard).

As one interviewee put it, the dashboard should be

a “one-stop-shop for non-technical people to

moderate comments” (I3). There was broad

agreement that it should have functionality to quickly

and easily browse, read, hide, delete and reset

comments flagged by users. One interviewee (I6)

suggested additional functionality in the form of a

live feed that would enable moderators to scan

comments as they are submitted, while at the same

time acknowledging that the usefulness of such a

feature would depend on the regularity and volume of

content submissions.

Most interviewees agreed that the user-generated

content should be available for export and integration

into websites in open, simple and commonly used

formats such as RSS or JSON. Some pointed out that

it would be good to have access to comments at

exhibition level (i.e. comments for a whole

exhibition) and object level (i.e. comments for a

specific exhibit).

Requirements for an In-gallery Social Interpretation Platform: A Museum Perspective

73

4.6 Deployment and Maintenance

Deploying a commenting system in the gallery space

is a critical aspect with wide-ranging design

implications. Not only does it have to comply with

health and safety regulations and the policies of the

institution, but it also needs to fit with curators’

visions for an exhibition and technicians’ views on

what is viable and practical in the gallery space.

When asked how peripheral or prominent a

commenting system should be in the gallery space,

most interviewees indicated that exhibit-level

commenting points in particular should be

unobtrusive and discrete so as not to distract from

exhibits but not be so discrete that they completely

disappear. One interviewee suggested that in his

experience there would be no problem with visitors

not engaging with inconspicuous commenting points

as they are “naturally inquisitive and explore

technology bits in exhibitions” (I3). Others suggested

putting up signage explaining the purpose of the

system, which again should be as discrete as possible.

Look and feel was pointed out as one of the most

important aspects with one interviewee warning that

commenting points must not look like a “tablet in a

box” (I4) and another urging to “make sure it looks as

slick as it possibly can” (I3). Ideally, commenting

points should look “like a continuation of the signage

to read some comments” (I2), with several

interviewees suggesting e-ink technology in this

context. One interviewee pointed out that a slanted

display mount would be more ergonomic to use for

people of different heights (e.g. children).

While interviewees from a larger organisation

were clear that they would develop their own display

enclosures that fit in with the exhibition design, others

from smaller organisations preferred displays to come

complete with an enclosure ready to mount.

Similarly, interviewees from the larger organisation

were positive that they would plug the display into a

mains power supply, while interviewees from smaller

organisations preferred them to be battery operated as

installation is one of their main concerns.

4.7 Summary of Findings

With regard to content moderation, most interviewees

supported the idea of post-moderation supported by

visitors flagging content they find inappropriate. The

system should notify moderators when content is

flagged by users, with notifications sent to both

moderators' desktops and mobile devices so that they

can react quickly even when away from their desk.

Once notified, moderators should be able to browse

user-generated content without the need to be present

at the related exhibit and to easily find, read, block or

un-block flagged content.

Interviewees were generally cautious with regard

to collecting or displaying additional information

about comment authors, with some questioning its

added value when interpreting comments and others

seeing it as a potential barrier to participation. There

was broad consensus that any provision of metadata

should be optional at the point of submission and that

no registration or login should be required, including

third-party logins that would tie comments to the

author's online profile.

Openness of a commenting system in terms of

access to comments was discussed by participants

mainly in the context of social media integration,

which was seen as potentially beneficial for the

museum but not an essential requirement, with some

interviewees stressing that it should not complicate

the interaction or exclude visitors without a social

media presence. Openness with regard to allowing

remote commenting as opposed to requiring physical

presence in the gallery to submit comments was seen

by some participants as an intriguing idea with

interesting new use cases, but overall not a core

quality of an in-gallery commenting system.

Most interviewees recognise that ownership and

reuse of comments is a sensitive topic and support the

idea of informing visitors about how their comments

might be used, in particular with respect to access,

archiving and potential commercialisation. Overall

there was support for the idea of displaying

information about content ownership and reuse at the

point of submission, however, some interviewees

stressed that any such notice should be unobtrusive

and not create a barrier to participation. With regard

to technical aspects, participants pointed out that the

system should store comments and interaction

statistics in an open format to support data analysis

and unspecified future uses.

Backend requirements for an in-gallery

commenting system were largely informed by

preceding discussions concerning the moderation and

reuse of content. Most participants suggested a

dashboard-like administration interface that should

be easy to use and suitable for content moderation by

non-technical staff. The dashboard should offer

functionality to browse, read, block, delete and reset

comments flagged by users. It should also provide

access to comments in open and commonly used

format such as RSS or JSON, ideally supporting

syndication at both exhibition and exhibit level to

allow integration with the museum web site.

CHIRA 2019 - 3rd International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

74

With regard to deployment and maintenance,

there was broad agreement among participants that

commenting points should not distract from the

exhibit and be presented in a way that is visually

pleasing and integrates with the exhibition design. On

a practical note, they should be provided to museums

with or without casings, depending on the preferences

of the host organisation, and support both mains- and

battery-powered operation to widen the range of

deployment options.

Together, these findings offer valuable insights

from museum professionals that can inform critical

design aspects of commenting systems including

content moderation, metadata, ownership and reuse,

openness and integration with other systems, backend

requirements and technical capabilities concerning

deployment and maintenance.

5 LIMITATIONS

With regard to validity, the main limitation of this

study is that findings are based on only seven in-depth

interviews. While this weakness is mitigated to some

extent by the range of participants' backgrounds, roles

and organisations, the study makes no claim to

exhaustively treat the discussed topics or to quantify

any results. Rather, it uses the issues, concerns and

preferences raised by museum staff as an indication

for required design features and functionality. Given

the formative character of the study, this approach is

supported to some extent by research in the field of

Human Computer Interaction, where Nielsen and

Molich (1990) found that in heuristic evaluations five

to seven participants typically find 75% to 85% of

problems in a system. While not directly transferable,

it indicates that even a small sample of seven

participants can flag up a large proportion of relevant

aspects to inform system design from a museum

perspective. It is also worth noting that a larger

sample size would be likely to add to further qualify

but not invalidate identified requirements.

Other limitations include that data was collected

through a mix of interview methods including email,

video link and in person, resulting in answers being

recorded at different levels of granularity, and that the

data was coded by a single researcher, leaving the

analysis open to potential investigator bias when

interpreting answers and identifying themes. The

study tries to mitigate both of these aspects by

employing a two-stage data analysis process, which

seeks to level out differences in data granularity in an

initial data reduction stage and overall aims to reduce

subjectivity and bias by separating low-level

emergent coding from higher-level interpretation

(Miles and Huberman, 1994).

With regard to transferability, many of the

findings reflect general concerns and constraints of

gallery environments with regard to commenting in

museums. While the interviews aimed in first place to

inform the design of SOLs, the findings are also

relevant to the design of other commenting systems,

particularly ones that collect and display comments in

the gallery space.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This paper contributes a professional perspective on

commenting in museum based on interviews with

museum staff from a range of institutions and roles. It

complements a survey of visitor perspectives on

commenting in museums (Winter, 2018) with a view

to identifying requirements for an in-gallery

commenting system that meets the needs of both

museums and their visitors.

After a brief review of literature on related topics,

including learning, participation and "user languages"

in museums, design guidelines for interpretive

resources, museums as curated environments, social

interpretation by visitors and moderation approaches

for user-generated content, the paper discusses the

methodology and findings of seven in-depth

interviews with museum professionals. The

interviews offer a spectrum of museum perspectives

reflecting the different organisational roles of

participants and draw on a deep understanding of

relevant museum practice. They cover a broad range

of aspects relating to in-gallery commenting in

museums, including content moderation, comment

metadata, conservation and reuse of comments,

system access and openness, backend requirements

and deployment and maintenance, which are

discussed in the context of high-level requirements

that can inform system design and development from

a museum perspective.

The range of topics and views is not exhaustive

and certainly could be extended with a larger sample

size and more extensive interviews, however, this

limitation does not invalidate the identified issues and

expressed views, which provide useful pointers for

the development of in-gallery commenting systems.

While carried out in the context of developing SOLs

as a particular instance of an in-gallery commenting

system, it is hoped that the findings will be useful to

other researchers in this field and to practitioners who

design platforms collecting and displaying visitor

comments in museums.

Requirements for an In-gallery Social Interpretation Platform: A Museum Perspective

75

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank our interviewees from

Science Gallery Dublin, the Regency Town House

and Phoenix Gallery Brighton for kindly sharing their

valuable insights.

REFERENCES

Adams, M. and Stein, J. (2004). Formative Evaluation

Report for the LACMALab nano Exhibition. Los

Angeles County Museum of Art, LA, CA. Available

http://www.participatorymuseum.org/LACMA_NAN

Oreport_final.pdf. Retrieved 04 Apr 2019.

Bagnal, G., Light, B., Crawford, G., Gosling, V., Rushton,

C. and Peterson, T. (2013). The Imperial War

Museum's Social Interpretation Project. Project report.

Digital R&D Fund for the Arts. Available

http://usir.salford.ac.uk/29146/1/Academic_report_

Social_Interpretation2.pdf. Retrieved 04 Apr 2019.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social Learning Theory. New York:

General Learning Press.

Barthel, R., Hudson-Smith, A., Jode, M. D. and Blundell, B

(2010). Tales of Things The Internet of ‘Old’ Things:

Collecting Stories of Objects, Places and Spaces. pp. 1–

6. Available: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/

viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.372.4996&rep=rep1&t

ype=pdf. Retrieved 16 Apr 2019.

Benkler, Y. (2002). Coase’s Penguin, or, Linux and The

Nature of the Firm. Yale Law Journal, 112, pp. 369–

446.

Bitgood, S. (1996). The Role of Attention in Designing

Effective Interpretive labels. Journal of Interpretation

Research, 5(2), pp. 31–45.

Bradburne, J. M. (2000). Interaction in the museum:

Observing Supporting Learning. PhD Thesis, Faculty

of Science, University of Amsterdam.

Bradburne, J. M. (2002). Museums and their languages: Is

interactivity different for fine art as opposed to design?

Paper Presented at the Interactive Learning in Museums

of Art Conference, Victoria and Albert Museum,

London, May 2002, pp. 1–17.

Bruner, J. (1973). Going Beyond the Information Given.

New York: Norton.

Engeström, J. (2005). Why some social network services

work and others don’t - Or: the case for object-centered

sociality. Available http://www.zengestrom.com/blog/

2005/04/why-some-social-network-services-work-and-

others-dont-or-the-case-for-object-centered-sociality.

html. Retrieved 04 Apr 2019.

Falk, J. H. and Dierking, L. D. (2000). Learning from

Museums. Visitor Experiences and the Making of

Meaning, Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press.

Fichter, D. (2006). Web 2.0, library 2.0 and radical trust: A

first take. Blog on the Side. Available

https://web.archive.org/web/20170923081932/http://li

brary.usask.ca/~fichter/blog_on_the_side/2006/04/web

-2.html. Retrieved 16 Apr 2019.

Forrest, R. (2013) Museum Atmospherics: The Role of the

Exhibition Environment in the Visitor Experience,

Visitor Studies, 16(2), pp. 201-216.

Girardeau, C., Beaman, A., Pressley, S. and Reinier, J.

(2015). Voices: FAMSF: Testing a new model of

interpretive technology at the Fine Arts Museums of

San Francisco. Proceedings of Museums and the Web

2015 (MW2015), pp. 1–15.

Gray, S., Ross, C., Hudson-Smith, A. and Warwick, C.

(2012). Enhancing Museum Narratives with the QRator

Project: a Tasmanian devil, a Platypus and a Dead Man

in a Box. Proceedings of Museums and the Web 2012

(MW2012), pp. 1–12.

Hein, G.E. (1998) . Learning in the Museum. Routledge.

IPO (2015). The rights granted by copyright. UK

Intellectual Property Office. First published 26 March

2015. Available: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/the-

rights-granted-by-copyright. Retrieved 16 Apr 2019.

Kelly, L. (2006). Museums as Sources of Information and

Learning. Open Museum Journal. Contest and

Contemporary Society, 8, pp. 1–19.

Knorr-Cetina, K. (1997). Sociality with Objects: Social

Relations in Postsocial Knowledge Societies. Theory,

Culture & Society, 14(4), pp. 1–30.

Kolb, D (1984). Experiential Learning as the Science of

Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice Hall.

Latham, K.F. (2013) Numinous Experiences With Museum

Objects, Visitor Studies, 16(1), pp. 3-20.

Loomis, R. J. (1983). Four evaluation suggestions to

improve the effectiveness of museum labels.

Publication of the Texas Historical Commission, July

1983, pp. 1-7.

Maye, L. A., McDermott, F. E., Ciolfi, L. and Avram, G.

(2014). Interactive Exhibitions Design - What Can We

Learn From Cultural Heritage Professionals?

Proceedings of NordCHI 2014, pp. 598–607.

Miles, M.B. and Huberman, A.M. (1984). Qualitative Data

Analysis. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Nielsen, J., and Molich, R. (1990). Heuristic evaluation of

user interfaces. Proceedings of CHI’90, pp. 249–256.

Oomen, J. and Aroyo, L. (2011). Crowdsourcing in the

Cultural Heritage Domain: Opportunities and

Challenges. Proceedings of the 5th Intl Conference on

Communities and Technologies,, pp. 138–149.

Russo, A., Watkins, J., Kelly, L. and Chan, S. (2008).

Participatory Communication with Social Media.

Curator: The Museum Journal, 51(1), pp. 21–31.

Screven, C. G. (1969). The Museum as a Responsive

Learning Environment. Museum News, 47(10), 7–10.

Screven, C.G. (1992). Motivating Visitors to Read Labels.

ILVS Review, 2(2), pp. 183-211.

Simon, N. (2010). The participatory museum. Museum 2.0.

Available http://www.participatorymuseum.org/.

Retrieved 04 Apr 2019.

Stevens, R. and Toro-Martell, S. (2003). Leaving a trace:

Supporting museum visitor interaction and

CHIRA 2019 - 3rd International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

76

interpretation with digital media annotation systems.

The Journal of Museum Education, 1(272), pp. 1–29.

Tröndle, M. and Wintzerith, S. (2012). A museum for the

twenty-first century: the influence of “sociality”on art

reception in museum space. Museum Management and

Curatorship, 27(5), pp. 461–486.

Valenzuela, D. and Shrivastava, P. (2008). Interview as a

method for qualitative research. Southern Cross

Institute of Action Research (SCIAR). Available

https://www.public.asu.edu/~kroel/www500/Interview

%20Fri.pdf. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

van Loon, H., Gabriëls, K., Teunkens, D., Robert, K.,

Luyten, K., Coninx, K. and Manshoven, E. (2006).

Designing for interaction: Socially-aware museum

handheld guides. Proceedings of NODEM 06, pp. 1–8.

vom Lehn, D. and Heath, C. (2003). Displacing the Object:

Mobile Technologies and Interpretive Resources.

Proceedings of Archives and Museum Informatics

Europe (ICHIM 2003), Ecole du Louvre, Paris.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978) Mind in Society. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Winter, M. (2014). Social Object Labels: Supporting Social

Object Annotation with Small Pervasive Displays. In

Proceedings of 2014 IEEE International Conference on

Pervasive Computing and Communication (PerCom)

2014, pp. 489-494.

Winter, M. (2018). Visitor perspectives on commenting in

museums. Museum Management and Curatorship,

33(5), pp. 484-505, DOI: 10.1080/09647775.2018.

1496354.

Winter, M., Gorman, M.J., Brunswick, I., Browne, D.,

Williams, D. and Kidney, F. (2015). Fail Better:

Lessons Learned from a Formative Evaluation of Social

Object Labels. In Proceedings of 8th International

Workshop on Personalized Access to Cultural Heritage

(PATCH2015), pp. 1-9.

Requirements for an In-gallery Social Interpretation Platform: A Museum Perspective

77