Business Intelligence Process Model Revisited

Pasi Hellsten

a

and Jussi Myllärniemi

b

Information and Knowledge Management Unit in Faculty of Management and Business, Tampere University, Finland

Keywords: Business Intelligence, Business Intelligence Process Model, Decision-Making, Organizational Development.

Abstract: Today many organizations have come to value knowledge as a production factor. Thus, there is a constant

need for getting the information in and sorted. Business intelligence (BI) is a process for systematic acquiring,

analyzing, and disseminating data and information from various sources to gain understanding about the

business’s environment. This is required for supporting decisions for achieving organization’s business

objectives. Literature has introduced models for planning and executing BI. However, as business

environments and technologies evolve in a rapid pace, are the models still applicable? Not all recent issues

are taken into consideration in the previous models. BI is considered to be integrated into business processes,

so the similar evolution is expected to take place. There are two studies investigating BI instigating this study,

but there are still questions to be answered. Literature on different models and findings of these studies were

combined to form a vision to better match reality. Various issues like users’ active involvement, real-time

analysis and presentation, and social media resources were brought up. Practitioners can use the approach to

assess their current state of BI activities or planning the organization of BI program.

1 INTRODUCTION

“When my information changes, I change my mind.

What do you do?”

1

What indeed and how does this

changed information get to the decision maker? We

know that organizations are struggling with data and

information overflow (Schwarzkopf, 2019; Virkus et

al., 2017). Information and communications

technology (ICT), while helping the organizations in

their tasks, is also creating vast amounts of data all

the time. The amount of data is growing at

exponential rate

2

. The trouble is no longer, whether

one has the data and information for the decision-

making, but to distinguish what is relevant. This

phenomenon, among others, has caused the

emergence of the business intelligence (BI) concept

(Shollo and Galliers, 2016). Even though the BI as a

discipline, and various models in that area, are not

very old

3

, already during their lifespan the business

a

https://orcid.org/ 0000-0001-7602-1690

b

https://orcid.org/ 0000-0002-2846-0426

1

Credits for this quote have been given, in addition to

Economist J.M. Keynes, to at least Paul Samuelson and

Winston Churchill. However, according to our opinion,

the reasoning favours John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946),

c.f. http://quoteinvestigator.com/2011/07/22/keynes-chan

ge-mind/

environment has undergone changes and

developments. This may cause the need for updated

thinking in this area. The ever-evolving environment,

developed during recent years, has features that affect

BI thinking. Features like even further networked

businesses, newer and continuously changing

technologies, Internet of Things, big and open data,

and just the information overflow in general are

transforming the operations. For example, social

media as part of BI can provide improvements but

also bring up novel challenges (Ketonen-Oksi et al.,

2016; Xue et al., 2018).

Literature defines BI as a systematic process for

knowingly collecting and analyzing data and

information from all possible sources to produce

insights of the competitive environment, business

trends and daily operations (Murphy, 2016). These

insights aim to support decisions that promote

organization’s business goals. BI also includes

2

According to IBM 2.5 quintillion bytes of data is created

every day. http://www-01.ibm.com/software/data/

bigdata/what-is-big-data.html

3

On the origins of the phrase, there is more than one theory.

According to one, the phrase BI was introduced in

organized manner in late nineties by IBM as they

connected it with their database and data warehouse

solutions.

Hellsten, P. and Myllärniemi, J.

Business Intelligence Process Model Revisited.

DOI: 10.5220/0008354503410348

In Proceedings of the 11th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2019), pages 341-348

ISBN: 978-989-758-382-7

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

341

assessing both the quality of the information sources

and the significance of the insights (Brody, 2008;

Fleisher and Bensoussan, 2015). However, our

studies show that organizations claiming to be

executing BI do actually a variety of things more or

less related to processing data and information into

knowledge and insights.

BI is nothing new. Already one of the most first

writings of management, Sunzi

4

(2012), dating back

some two and a half millennia, stressed the

importance of information and knowledge used to

promote the set objectives. No organization can

operate in vacuum. All organizations need, and have,

information and knowledge about their operating

environment and stakeholders therein. However,

there are differences on in how an organized manner

it is done, on which level it is done and by whom.

Literature presents several BI frameworks and

process models. They all are based on certain

interpretations and presumptions of their makers. The

models mirror findings of cases of the time the studies

were conducted in.

Changes and trends described above affect the

whole organization. BI must be connected to all

business processes of an organization, because only

by this connection it is able to draw high quality

information from everyday operations and

information products formed from this empirical

material to bring value to decision-making. Hence,

we claim that there is a need for revision or even an

updated process model. We ask ‘how theoretical

consideration of BI is suitable for BI practice’.

Based on both the literature and empirical

findings our goal is to present a comparison between

models for BI and execution of these actions in

organizations. The study bases on theoretical findings

of BI, i.e. process models, in the literature and

empirical studies of organizations’ use of BI. Based

on empirical evidence we point out trends,

phenomena and practices that have an influence on

BI. Thus, justifying useful re-thinking of BI

framework.

The paper is organized as follows. BI concept is

defined and selected in section two; in our opinion,

centric process models for BI are introduced. In the

next section, section three, findings of two studies are

explained and they are further analyzed in section

four in which the theme is also discussed. The fifth

section summarizes the conclusions of the paper.

4

There are multiple ways to write the originally Chinese

name with Latin letters: Sun Zi, Sun Tsu, Sun Tzu, Sunzi.

2 BUSINESS INTELLIGENCE

MODELS AND RELATED

RESEARCH

Theme of BI has been studied and used by researchers

to talk about process that produces information for

strategic decision-making for sometime now (Brijs,

2016; Intezari and Gressel, 2017). However, BI as a

term became more popular in late 1990’s (Chen et al.,

2012). Defining the contents of BI has caused

considerable debate (Calof and Wright, 2008). It can

be seen as an umbrella-like phrase or term under

which one combines different tools, applications and

methods (Turban et al., 2008). Moreover, BI has

many similar or related concepts and terms such as

competitive intelligence, competitor intelligence,

marketing intelligence, business analytics, business

intelligence and analytics and big data analytics.

Terms differ because of different nature of

information (external – internal), scope of

information gathering (narrow – broad), the way

information is managed (technological – conceptual),

or even because of its geographical location (cf.

Fleisher and Bensoussan, 2015; Pirttimäki, 2007).

Common for all terms is to process data and

information to form and use that are more

meaningful.

Pirttimäki (2007) defines BI as a dualistic

concept. It refers to refined information and

knowledge, means information about organization’s

business environment, and of the organization itself,

and its state in relation to its markets (customers,

competitors, and economic issues). In addition, a

process produces refined information and knowledge

(information products) for the management and

decision-makers. Therefore, BI may be defined as a

framework for refining information to knowledge and

a framework for refining data masses to information

products used in operations and decision-making.

When taking the narrower approach of BI

considering only the internal sources of information,

the discussion often turns to different information

systems, data warehousing, and reporting and

analytics tools. These are important in all BI activities

and should be considered within them. For example,

data warehouses are used to store the information

gathered from various sources and analytics tools

offer aid in handling that information. Furthermore,

the so-called ETL (Extract, Transform and Load)

operation is highly relevant in BI process as the data

Either way, it is valued reading in many institutions and

by many influencers

KMIS 2019 - 11th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

342

compiled and gathered usually is in different source

systems and forms and thus it is not possible to use or

compare it directly (Dayal et al., 2009; Debortoli et

al., 2014). In ETL the data is first extracted from the

desired sources (homogeneous or heterogeneous),

then transformed into chosen proper format for

analysis and querying purposes, and finally loaded

into its final destination where it is applied. Often, in

practice, these phases are executed in parallel in order

to improve efficiency and cut off idle time from the

process. (Chaudhuri and Dayal, 1997)

BI relies largely on data warehousing. Without

well organized and executed, effective if one will,

data warehouse, BI will not able to perform in the

expected, most efficient way. Previously introduced

ETL plays a centric role in data warehousing,

simultaneously crystallizing the link between the two.

However, in this study the concept of BI does not

refer just to internal or external information, and

neither to any specific information type. BI refers to

the processes, techniques and tools, which support

faster and better decision-making.

As shown, BI briefly means systematically

deriving knowledge and insights from data and

information to support decision-making (Brody,

2008; Fleisher and Bensoussan, 2015). Knowledge in

this context refers to the outcome of human actions

that take place e.g. in decision-making situations.

Knowledge is based on information combined with

experiences. It is acquired from information, which in

turn is processed from data (Choo, 2002). Knowledge

is essential for decision-makers (Thierauf, 2001). In

other words, decision makers pursue these

meaningful insights in order to better make sense of

proceedings and ultimately to add value to the

organization.

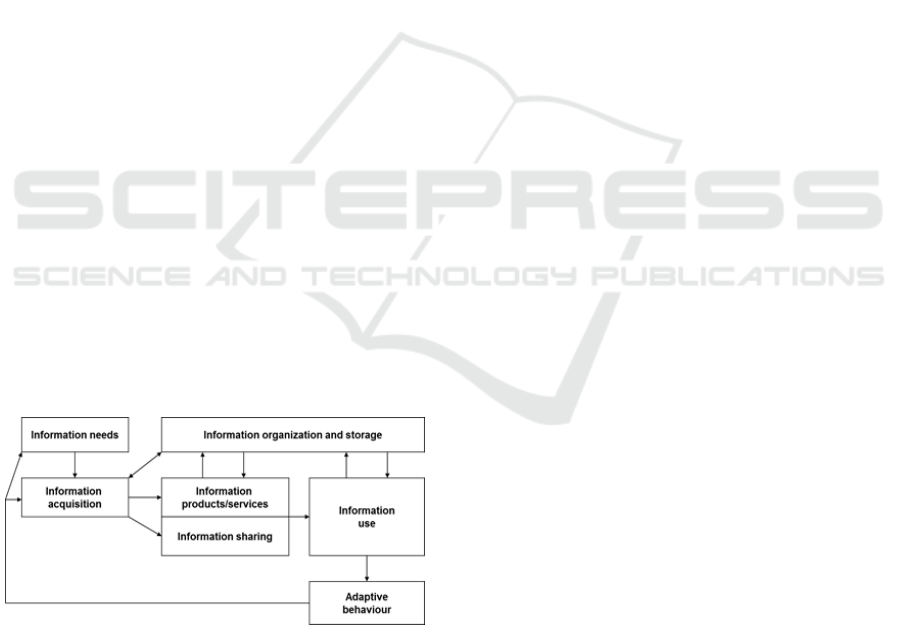

Figure 1: Process model of information management

(Choo, 2002).

There are various different models and

descriptions for BI. Understood in wider sense, BI

process is close to management of any information.

Hence, we will start by introducing Choo’s (2002)

established process model for information

management and set the ground for our

argumentation. This model is presented in Figure 2.

There are six stages identified. The first stage is

information needs definition. Information needs,

composed based on changes and uncertainties

between organization’s industry, strategy and

operational environment, have to be defined so they

can be satisfied as well and efficiently as possible.

The needs are defined by subject-matter requirements

and situation-determined contingencies. The second

stage, information acquisition, is conducted based on

the previous definitions, i.e. it must adequately

address the needs. The specified information sources

act as a foundation for gathering the expedient

information or data. It plays no role whether

organization’s information sources are external or

internal.

Third stage is organizing and storing the

information. The objective is the creation and build-

up of organizational memory. The acquired

information must be organized and stored

systematically to enable organizational learning. This

information must be analyzed and processed to a

compact form into information products and services

(e.g. reports, reviews) targeted at information users.

This is the stage four. The goal of information

distribution which follows as the stage five, is not

only to increase the sharing the information to satisfy

the needs of decision-makers but also to enable

creation of new insights and knowledge based on the

existing knowledge and know-how.

Information, in form of knowledge products, gets

its final meaning when it is used. In the sixth stage of

the process information and knowledge are formed

into new information and understanding. After this, in

the last stage, information is applied to practice in

problem solving and decision making situations. By

using the knowledge products and by adjusting the

operation, the cycle starts anew. It should be noted,

however, that processing data into information and

knowledge is an iterative process and that the

fluctuation between stages is not always straight-

forward (Choo, 2002; Vitt et al., 2002).

A generic model of five stages is based on

multiple sources (Choo, 2002; Fleisher and

Bensoussan, 2015; Pirttimäki, 2007). The framework

takes into account the both views stated before:

refining information to knowledge and refining data

masses to information products. Pirttimäki (2007)

reminds that the order and existence of stages are

highly dependent on the organization and the

intelligence effort at hand. The goal of the process is

to produce organization-specific target-oriented

Business Intelligence Process Model Revisited

343

intelligence solutions instead of producing general

business information or knowledge (ibid.).

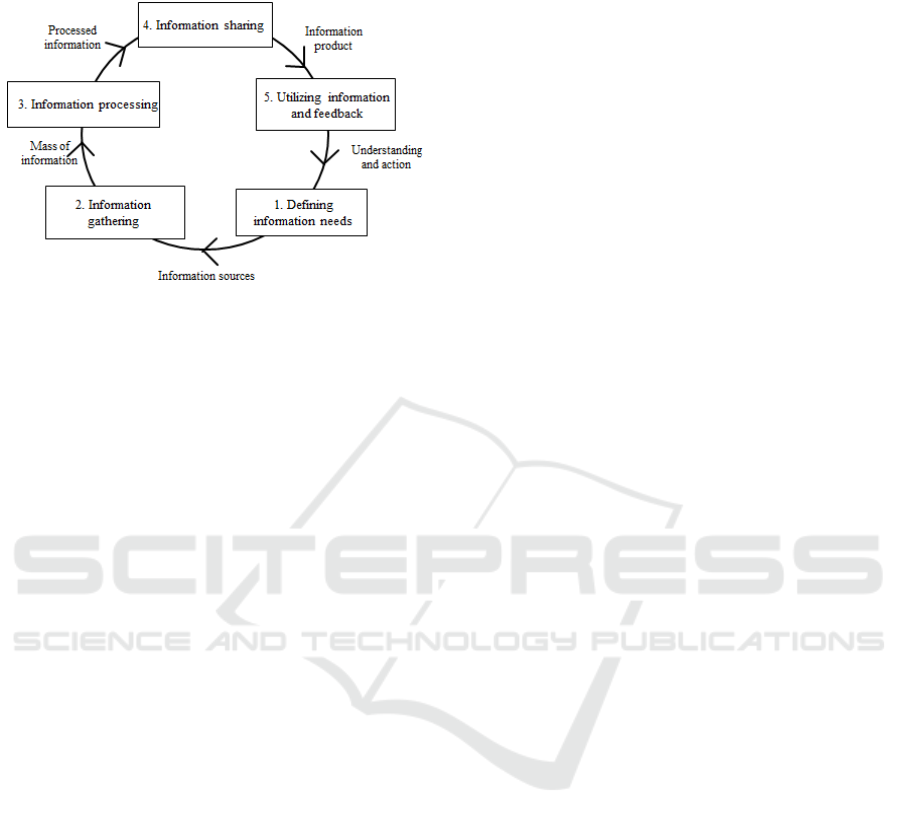

Figure 2: BI process (Myllärniemi et al., 2016).

The process starts with specification of

information needs. It requires a clear statement of the

key intelligence topics and more specific questions

concerning the current issues, problems, or trends

(Pirttimäki, 2007). The specified information needs to

dictate the information sources that act as a

foundation for gathering information or data after

having first been evaluated. This means monitoring

various sources and actually collecting the

information. The collected information is stored in

organization’s repositories.

Processing stage includes analyzing and

evaluating the gathered information, and representing

it in a compact form, i.e. information products.

Collected information is assessed and connected to

existing information, e.g. structured information of

external environment is connected to the expertise of

employees. This is where most BI tools come in

handy. Yet, existence of information and information

products is not enough. Dissemination stage is about

sharing the knowledge and insights between the

users. The results need to be communicated to the

right recipient, at the right time and via most suitable

tools. In the final stage, utilization, information is

used in problem solving and decision-making.

Utilizing information and knowledge creates

understanding, and by subsequent adjusting of the

operation, the BI cycle starts over.

Described general BI model does not significantly

differ from Choo’s (2002) model. However, it takes a

step further as it notices that there are some typical

attributes and characteristics in BI, such as mass of

information, compared to any information

management.

Third model we will consider is a social media

enabled process model (Beck et al., 2014; Vuori and

Okkonen, 2012). We will not explain the process

itself as it fundamentally has the same stages as in the

model presented previously. However, it adds an

important dimension/attribute to the process: the

different social media tools as a source for collecting

data and channel for distributing insights. (Vuori and

Okkonen, 2012) argue it is a swirl-like activity of

overlapping processes. Personalization instead of

codification, pull instead of push, and active

employee participation in the process are

fundamental issues in it.

The process models introduced here are not built

in a continuum, i.e. the latter ones are not meant to be

directly developed from or adding to the earlier

models. Instead, each represent process for

information management with different background

assumptions and objectives, e.g. Choo is based on

organizational learning whereas the BI process

(Figure 2.) has knowledge based value creation as a

starting point.

3 THE BI STUDIES

The studies forming the empirical part behind this

paper give practical view of BI on operative level as

most of the respondents were working as analysts or

in equivalent positions. It was investigated how

different BI operations are executed in business

environments and where they are headed in the future.

(Helander et al., 2015, Helander et al., 2018,

Tyrväinen 2013) In the first study participated 56

large Finnish companies (based on their turnover).

The second study was targeted differently; to

organizations in which the university graduates from

a business information management program

majoring in BI were employed. There were 78

respondents. Both were executed as surveys. In the

next chapters we present the main findings and

elaborate the results from our study’s perspective.

The results show that all the organizations

consider having BI activities in place. These are often

also called BI, yet also other names for similar

activities are used (such as competitive intelligence,

marketing intelligence, management by knowledge).

BI is not always seen as an independent function but

it is merged with other functions. This leads to BI

being executed differently in different organizations.

This might occur even within one organization. The

precise number of people involved in BI activities is

difficult to estimate. The responsibility of BI has been

divided among two or more persons in over half of

the organizations. Various parts of BI are being

procured from outside operators or outsourced

completely. For example, in 87% of cases the news

KMIS 2019 - 11th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

344

feed originates from outside the organizations and

most of the bulk research is performed by specialized

operators

5

. The BI work done within organizations is

most often related to data and information processing

based on organizations’ internal systems or

personnel. Top management is the main user of BI

products – information products made with BI tools

or methods. Nevertheless, middle management and

various professionals use and participate in producing

the information and knowledge products generated by

the BI analysts.

Clear BI strategy or policy is absent in 69% of the

cases and 63% of respondents state that the BI has no

allocated budget. These statements underline the

vagueness of the practice of BI. Other areas of

business, e.g. customer relationship management

(CRM) or financial reporting are more clearly

understood, perhaps due to their longer existence or

more tangible nature. In over half of the cases, the

tasks are performed in unorganized manner; only in

47% of the organizations, the BI activities have

appointed a dedicated professional to take

responsibility over the related actions.

The BI products are meant for various decision-

making situations. These include the rather obvious

strategic planning and business development but also

sales and marketing alongside with CRM. In addition,

the financial departments are among the users of the

services provided by the BI specialists. Our studies

show that majority of these products are

predetermined: both the needs to be fulfilled and the

products needed. The object for the products, i.e.

information needs, are equally understandable;

customers, profitability, and the overall state of the

business in which the operation is performed. The

most utilized ways to identify critical information

needs are interaction with and interviews of the

information users and producers.

Looking at different stages of BI process,

organizations’ procedures to execute BI can be

shown. Information gathering is executed by surveys

and personnel queries by using intranet and social

media. Our second study shows that despite

organizational way to gather information, BI

professionals gather information personally from

interviews, face-to-face discussions and workshops.

Personnel is one of the main information sources,

71% organizations of the first study collect feedback

from BI end-users. However, organizations have

faced challenges in gathering information from

personnel. Information gathering activities are not

5

According to our study 87,5% of market research, 89% of

customer research, and 94,5% of brand research are

performed by outside operators.

conducted in a systematic way and the organization

culture does not nurture such behavior.

Information processing methods vary

significantly. The most utilized analysis techniques

are financial analysis, risk analysis and SWOT

6

.

When considering data and information processing

from different information systems planning

solutions, ad hoc queries, reporting and visualization

are the most frequent methods. According to the

second study the most used BI-tools are Microsoft

Excel (50%), QlikView, SAP (both approx. 10%) and

IBM Cognos (less than 10%). E-mail is the most used

information sharing method. The studies emphasize

the importance of visualization and analytics in the

future. Social media is a rising field of application.

The studies show that benefits achieved by BI are

more qualified information for decision-making,

rationalization of information gathering and

analyzing and raising knowledge capital. Unreached

benefits are quicker response to competence and

expedited decision-making processes. With BI

organizations want answers to questions related to

forecasting (e.g. so called subtle signals (Bird et al.,

2018; Malan and Kriger, 1998)) and better

understanding of markets.

Further investments to issues such as monitoring

competitors and industry, reporting activities and

customer management is planned by 83% of the

organizations. The organizations’ targets of

developing BI include:

● Better and more efficient use of current BI

systems

● Deepening degree of information processing

● Identifying critical information needs

● More effective knowledge sharing

The results have already some longitudinal

confirmation as studies show similar results starting

already in year 2003. Volume and velocity of

information will increase. At the same time,

organizations want more efficient utilization of

current systems and BI-tools but demand is for more

sophisticated and analytical BI methods. Based on

our studies other trends in BI are mobilization,

visualization and real-time capabilities. Every large

company executes BI, the activities understood as

them vary. These form challenges for modeling the

BI-processes. In the next chapter, we will elaborate

these thoughts to meet the organizations current

demands and future trends.

6

Strenghts, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats. This and

the two others belong to basic analysis tools to offer more

understanding over the business-related matters.

Business Intelligence Process Model Revisited

345

4 THE COMPARISON BETWEEN

BI PROCESS MODEL AND

PRACTICE

Essential factors behind effective decision-making

are high-quality information and managements’

proactivity (Thierauf, 2001). Organizations’ ability to

use information and knowledge in decision-making is

based on users’ personal characteristics and

organizations’ culture and way of working. Our

studies, in addition to previously introduced

literature, indicate that BI should be integrated to

other business processes and information systems and

connected to personnel. Integration intensifies

knowledge availability, improves knowledge quality

and thus makes information products more valuable

through their use. In the end, all these help to improve

decision-making.

Our studies show that organizations are planning

to increase investments to BI activities. They are

striving for goals such as deepening the degree of

processing information and identifying critical

information needs more effectively. In this chapter,

we link the literature to practice and show how an

updated conception of BI is needed when aiming to

achieve those goals.

Top management is the main user of BI products,

but BI products are used at almost every level of

organizations. Problem formulation is not only top

management’s responsibility. Similarly, continuous

feedback and active updating of information needs on

all levels of operation improves the quality of

information products and makes knowledge

processing more fluent. This allows the analysis to

dig deeper into actual problems behind the

information needs - the users may also be relevant

information sources. Based on our studies, BI

analysts use quite often their personal inference skills

to define information needs and to gather information

from relevant sources. The information needs are

based on subject-matter requirements and situation-

determined contingencies (Choo, 2002). That is

obvious as some classes of problems are best handled

with the help of certain types of information. To

define these more efficiently, seamless cooperation

between BI users and analysts is necessitated. The

question arises, whether all the needs are able to be

anticipated. Developments both in business

environment as well as in internal operations would

need to be considered in advance. Only then, this

form of methodicalness is possible to satisfy the

needs without ad hoc –type of BI function.

Based on our studies, enabling and enhancing

real-timeliness in decision-making and variability of

fulfilling the information needs during BI processes

are features of modern BI. BI processes introduced in

chapter 2 are continuous in nature but do not

explicitly take into consideration aforementioned

features or active participation of BI users and

analysts. In addition, integration to various

information sources is not presented very clearly.

Traditional classification of information sources is

between internal and external sources. Newer trends,

like social media and big and open data, outsourcing

and personnel as an information source challenge

organizations’ traditional BI as well as constantly

improved BI tools, i.e. social media based ways to

share information.

Due to the flux of modern business environment

and emerging trends introduced before, BI process

model should be updated. Novel BI methods as well

as various, heterogeneous information sources need

to be adapted to practice in problem solving and

decision-making situations. We acknowledge the

need to integrate these thoughts, newer aspects and

requirements, to the centric BI models (Choo, 2002;

Pirttimäki, 2007; Vuori and Okkonen, 2012) and thus

recognizing a need to construct a newer view of the

BI process.

The previous BI models present the process as a

continuum. As contrived as it may sometimes seem,

the problem formulation is the starting point for the

process. The action is originated by a need for more

information; there is a problem, a decision needing to

be made in a business case. A need for an

information/knowledge product is formulated. The

data needed for the decision is usually defined by the

original problem. The problem may or may not be

related to the actual business processes. The problem

may as well be something completely different as the

business environment is everything around the

organization. The organizations interface to the

environment is not always clearly defined or planned,

nor limited solely to the top management. Thus the

problem may arise also from elsewhere, which

implies the need for empowering the middle

management and even employees to initiate the

process.

The required data defines the source. The source

may be more traditional operational systems, such as

ERP’s or CRM’s, which still are quite possible, and

usable, sources for the business needs. The newer

sources might include open data, i.e. data repositories

made accessible by for example a public operator, or

social media applications that have a purposeful

KMIS 2019 - 11th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

346

function for this special need. The format of the data

may vary.

The studies showed that personnel is one of the

most important information source. Organizations

have faced difficulties in collecting information from

personnel. The multiplicity and variety of data

sources makes it necessary for an organization to

build newer forms and ways of extracting the data

from these sources, whether they are from internal or

external sources. In addition, as the relevant

information may as well come from people or from

social media it is notable that information gathering

is not solely a technical phase in the process.

Fleisher and Bensoussan (2015) claim that

information analysis is just one step of a larger

process. For example, problem formulation and

purpose of using BI product guide the selection of BI

tool. However, our studies show the shift towards

more sophisticated BI tools and methods. For

example, the study respondents say that significance

of visualization, data discovery and social media tools

will increase in the future. However, more traditional

methods, e.g. email, are still prevailing ones in

businesses. The range of BI tools may be offered and

applied to satisfy the needs presented in the problem

formulation. Basically this means to produce the

information products. The range of these products

cover a variety of various needs always case-

specifically designed. The product may be a simple

report, or a graphic re-presentation of data. Or it may

be an elaborate presentation of the situational set of

data and a forecast of the environmental changes.

Obviously it varies how sometimes the ‘client’ is able

to define his/her needs better and some other times

less well. The bottom line is that the organization

using these tools based on these data sets is able to do

better and faster decisions that more accurately

predicts and anticipates the needed responses to

business needs set by the organizational strategy and

the ever-changing business environment.

Our studies and recent literature show that nature

of information decision-makers need has changed.

Real-timeliness and proactiveness are emphasized.

We have presented the BI process to be linear and

straightforward. This is not, however, the case in

practice. For example, problem formulation may get

input from the following stages as the information

needs be updated while either gathering the necessary

information, analyzing it, or using the created

knowledge in action. The feedback from the users and

other actors involved in the process also flows both

ways. Considering the need for evermore faster desire

for knowledge and real-time requirements this is

essential. It will not be efficient enough to always go

through the whole process; the activities in all phases

may need to be modified on the fly.

Real-time requirements, continuous cooperation

between BI producers and users, and demand for

proactiveness considering information products and

decisions are features BI must tackle. These features

have come up in BI studies previously but are

emphasized in the recent studies. Novel thinking is

needed in the modern business environment where

organizations are focusing more on monitoring

competitors and industry, reporting activities and

customer management. Diversity of information is

emphasized and using only organizations’ internal

information is deficient.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Business intelligence (BI) is a part of organization’s

actions. BI is a working practice or a process in which

data and information are refined into a more

meaningful knowledge in order to support decision-

making. The process itself retains various variables

and stages that make the process complicated. The

complexity is formed by the fact that the information

needs of the people and processes involved change

continuously, information sources are not limited to

organizations’ inner sources but vary and BI tools are

more and more sophisticated and more demanding for

their users. These along with facts that set pressure to

BI process, like demand for quicker and more

proactive decision-making, and organizations’

unstable business environment, makes process hard to

handle.

It is obvious that investing in BI activities

organizations gain benefits, like better quality of

information, faster decision-making and deeper

understanding of business environment. However, BI

does not suit for every organization. Organizations’

maturity of BI and size of organizations do have an

influence. With start-ups continuity of BI process

might be different though stages of process are

important to take into consideration. Our studies

targeted large companies and the results are

generalizable at some level concerning organizations

that do BI regardless their maturity of it.

Organizations may take advantage of the BI

model in various ways, for example, they may use it

just to get the grip of their overall BI standing, what

is their current state of affairs. The model may also be

used in planning and organizing the BI programs and

processes. Furthermore, the insights from the

benchmarking in this work can assist in making better

and more informed decisions, which is also the

Business Intelligence Process Model Revisited

347

fundamental purpose of BI thinking (Fleisher and

Bensoussan, 2015; Pirttimäki, 2007; Thierauf, 2001;

Vuori and Okkonen, 2012).

An important issue, that was not evident in the

research nor in the literature covered, was the role of

tacit knowledge. Obviously, organizations’

employees from all levels possess knowledge and

expertise that needs to be included in the insights

produced in the BI activities. This further highlights

the need to consider users of the BI products also as a

relevant source. Moreover, the nature and

characteristics of tacit knowledge, and challenges

presented by these, should be noted in the distribution

of insights. For example, an analyst is likely to form

a comprehensive understanding of the problem at

hand and issues related to it. Sharing this accumulated

knowledge is vital in order to represent the best

possible picture of reality for the decision-makers.

However, articulating tacit knowledge is not always

an easy task as there are several challenges (eg.

Haldin-Herrgard, 2000; Riege, 2005).

In this paper, we tackled this challenging issue by

representing more modern thinking of BI. Our goal

was to present a comparison of the BI models and to

point out some focal issues needing to be covered in

order to address these issues in one’s organization to

answer to modern environment’s requirements. The

presented models support organizations’ BI activities

but need to be updated to face the modern

requirements with some additional research.

REFERENCES

Beck, R., Pahlke, I., Seebach, C., 2014. Knowledge

exchange and symbolic action in social media-enabled

electronic networks of practice: A multilevel

perspective on knowledge seekers and contributors.

MIS Q. 38, 1245–1270.

Bird, R.B., Ready, E., Power, E.A., 2018. The social

significance of subtle signals. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 452.

Brijs, B., 2016. Business analysis for business intelligence.

Auerbach Publications.

Brody, R., 2008. Issues in defining competitive

intelligence: An exploration. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 3,

3.

Calof, J.L., Wright, S., 2008. Competitive intelligence: A

practitioner, academic and inter-disciplinary

perspective. Eur. J. Mark. 42, 717–730.

Chaudhuri, S., Dayal, U., 1997. An overview of data

warehousing and OLAP technology. ACM Sigmod

Rec. 26, 65–74.

Chen, H., Chiang, R.H., Storey, V.C., 2012. Business

intelligence and analytics: From big data to big impact.

MIS Q. 36.

Choo, C.W., 2002. Information management for the

intelligent organization: the art of scanning the

environment. Information Today, Inc.

Dayal, U., Castellanos, M., Simitsis, A., Wilkinson, K.,

2009. Data integration flows for business intelligence,

in: Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on

Extending Database Technology: Advances in

Database Technology. Acm, pp. 1–11.

Debortoli, S., Müller, O., vom Brocke, J., 2014. Comparing

business intelligence and big data skills. Bus. Inf. Syst.

Eng. 6, 289–300.

Fleisher, C.S., Bensoussan, B.E., 2015. Business and

competitive analysis: effective application of new and

classic methods. FT Press.

Haldin-Herrgard, T., 2000. Difficulties in diffusion of tacit

knowledge in organizations. J. Intellect. Cap. 1, 357–

365.

Intezari, A., Gressel, S., 2017. Information and reformation

in KM systems: big data and strategic decision-making.

J. Knowl. Manag. 21, 71–91.

Ketonen-Oksi, S., Jussila, J.J., Kärkkäinen, H., 2016. Social

media based value creation and business models. Ind.

Manag. Data Syst. 116, 1820–1838.

Malan, L.-C., Kriger, M.P., 1998. Making sense of

managerial wisdom. J. Manag. Inq. 7, 242–251.

Murphy, C., 2016. Competitive intelligence: gathering,

analysing and putting it to work. Routledge.

Myllärniemi, J., Hellsten, P., Helander, N., 2016. Business

Intelligence Process Model As A Learning Method.

TOJET Turk. Online J. Educ. Technol. December 2016,

1451–1456.

Pirttimäki, V., 2007. Business intelligence as a managerial

tool in large Finnish companies.

Riege, A., 2005. Three-dozen knowledge-sharing barriers

managers must consider. J. Knowl. Manag. 9, 18–35.

Schwarzkopf, S., 2019. Sacred Excess: Organizational

Ignorance in an Age of Toxic Data. Organ. Stud.

0170840618815527.

Shollo, A., Galliers, R.D., 2016. Towards an understanding

of the role of business intelligence systems in

organisational knowing. Inf. Syst. J. 26, 339–367.

Thierauf, R.J., 2001. Effective business intelligence

systems. Greenwood Publishing Group.

Turban, E., Sharda, R., Aronson, J.E., King, D., 2008.

Business intelligence: A managerial approach. Pearson

Prentice Hall Upper Saddle River, NJ.

Tzu, S., 2012. The art of war: A new translation. Amber

Books Ltd.

Virkus, S., Mandre, S., Pals, E., 2017. Information overload

in a disciplinary context, in: European Conference on

Information Literacy. Springer, pp. 615–624.

Vitt, E., Luckevich, M., Misner, S., Corporation

(Redmond), M., 2002. Business intelligence: Making

better decisions faster. Microsoft Press Redmond, WA.

Vuori, V., Okkonen, J., 2012. Refining information and

knowledge by social media applications: Adding value

by insight. Vine 42, 117–128.

Xue, Y., Zhou, Y., Dasgupta, S., 2018. Mining Competitive

Intelligence from Social Media: A Case Study of IBM.

KMIS 2019 - 11th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

348