Knowledge Management and Its Impact on Organizational

Performance in the Private Sector in India

Himanshu Joshi

a

and Deepak Chawla

International Management Institute, New Delhi, India

Keywords: KM Planning and Design, KM Implementation and Evaluation, Technology, Culture, Leadership, Structure,

Organizational Performance, Financial Performance, Private Sector, India.

Abstract: The study proposes a comprehensive model comprising of various relationships between antecedents to

effective Knowledge Management (KM) and organizational performance. A review of literature besides a

focus group discussion and a personal interview were used to design an instrument and propose seven

hypotheses. Data was collected from 127 managers working in private sector organizations in India. To test

the hypotheses, Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) analysis through Partial Least Squares (PLS) was used.

The results indicate that although all the hypotheses had the desired positive sign, five out of them were

significant. This paper presents empirical evidence of the role of KM planning and design (KMPD), KM

implementation and evaluation (KMIE), Technology in KM (TKM), Culture in KM (CKM), Leadership in

KM (LKM) and Structure in KM (SKM) in enhancing organizational performance. Further, improvements in

organizational performance leads to improvements in financial performance.

1 INTRODUCTION

Knowledge and its management have provided an

opportunity for organizations to differentiate itself

from its competitors. Knowledge Management (KM)

has different implications for different industries and

sectors. Since business performance, profitability,

market share, growth etc. are the key business drivers

for private sector, KM becomes a tool to build long-

term competitive advantage. The importance of KM

in the consulting industry, where the firm’s core

product is knowledge itself has been discussed by

Sarvary (1999). Similar other industries in India like

information technology, telecommunications etc. are

predominantly from private sector where knowledge

constitutes their core resource or asset.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. The

next section discusses the existing literature on KM,

factors which are critical for KM success, relationship

between KM factors and business performance.

Section 3 presents the research gaps and objectives of

the study. Next, the fourth section presents the

methodology which is followed by the findings of the

study in the fifth section. Finally, the paper closes

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4774-7983

with a discussion of the research findings and the

main conclusions of the study.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

For effective KM implementation, organizations need

to create processes and systems to capture, store,

disseminate, apply and evaluate knowledge sources

from internal and external stakeholders. In addition to

KM planning and implementation process, several

KM enablers have been suggested by researchers.

2.1 KM in Indian Private Sector

Sarvary (1999) defines KM as a process through

which firms create and use their institutional or

collective knowledge and includes three sub-process,

viz. organisational learning, knowledge production

and knowledge distribution. It refers to identifying

and leveraging the collective knowledge to help

organization compete and is the art of creating

commercial value from intangible asset (Sveiby,

2001). We defined it as a systematic, formal and

structured approach to develop socio-economic

Joshi, H. and Chawla, D.

Knowledge Management and Its Impact on Organizational Performance in the Private Sector in India.

DOI: 10.5220/0008494204270434

In Proceedings of the 11th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2019), pages 427-434

ISBN: 978-989-758-382-7

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

427

business systems where knowledge forms a key

component of all business inputs, outputs and

processes, to enhance capabilities of decision makers

and improve firm performance.

Although the importance and use of KM in private

sector organizations is unquestionable, the benefits

and KM outcomes may vary. In general, the design

and implementation of KM practices are a difficult

task for managers, and the effectiveness and success

of such practices depend heavily on their optimal

adjustment to organizational factors (Bierly & Daly,

2002).

2.2 KM Critical Success Factors

When conceptualizing a KM system, there is no

single approach that fits all sectors and industries. The

literature has many instances of different approaches,

frameworks and models developed and adapted

across different contexts to guide KM

implementation. While information technology is a

key enabler in KM, its important to realize that here

is much more to KM than technology alone. Lee and

Choi (2003) believe that KM enablers must be

structured based upon a socio-technical theory to

provide a balanced view between a technological and

social approach to KM. Therefore, KM should always

be viewed as a system that comprises of a

technological subsystem as well as a social one

(Wong and Aspinwall, 2004). Chong and Choi (2005)

identified 11 key KM components for successful KM

implementation (training, involvement, teamwork,

empowerment, top management leadership and

commitment, information systems infrastructure,

performance measurement, culture, benchmarking,

knowledge structure and elimination of

organizational constraints).

2.2.1 KM Planning and Design (KMPD)

Donate and Pablo (2015) have examined KM process

in the form of KM exploration (i.e. creation) and

exploitation (i.e. storage, transfer and application)

practices. It is a systematic process of identifying,

capturing and transferring information and

knowledge people can use to improve (O’Dell et al.,

2004). Prior research studies have identified many

key aspects in the KM processes such as: acquiring,

collaborating, integrating, experimenting (Leonard-

Barton, 1995); knowledge acquisition, knowledge

sharing and knowledge distribution (Nevis et al.,

1998). knowledge acquisition, knowledge conversion

into useful form, application and protection (Gold et

al., 2001); creation, storage/retrieval, transfer and

application (Alavi and Leidner, 2001); generation,

codification, transfer and application (Singh and

Soltani, 2010); acquisition, creation, storage and

application (Aujirapongpan et al., 2010).

2.2.2 KM Implementation and Evaluation

(KMIE)

According to Smith and McKeen (2004), the process

of KM must facilitate knowledge development (i.e.

identification, creation, harvesting and organizing)

and knowledge application (sharing, adaptation and

execution) and develop the linkages between the two.

2.2.3 Leadership in KM (LKM)

The biggest challenge to KM is getting support,

commitment, and a separate budget from top

management. Prior studies have highlighted the

importance of leadership in knowledge intensive

organizations in Malaysia (Chong, 2006) and in India

(Singh and Soltani, 2010).

2.2.4 Structure in KM (SKM)

Knowledge flow as a phenomenon not only occurs

through the conventional top-down approach but also

bottom-up and horizontal knowledge exchanges

(Mom et al., 2007). Smith and McKeen (2004)

proposes communities of practices within network of

people who create, disseminate, and retain

knowledge. Therefore, organization structures

determine the effectiveness of the working of such

communities.

2.2.5 Culture in KM (CKM)

KM is all about people and organizational culture and

has been advocated by researchers. KM is not very

useful in environments that are highly secretive or

overly competition driven. But, nurturing a climate of

trust and openness is a gradual and long-term process.

2.2.6 Technology in KM (TKM)

IT plays an active role in knowledge sharing and

dissemination. Smith and McKeen (2004) believe that

IT tools help knowledge managers deliver the right

knowledge at the right time, but do not tell what to

collect, how to collect or how to get people to use it.

KMIS 2019 - 11th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

428

2.3 KM and Its Impact on

Performance

Performance improvement due to KM can be

measured at three levels, i.e. individual, process and

business. But attaching a value to intangible assets is

difficult because of the associated uncertainties. The

frequently asked question is, how can you put a value

to knowledge? KM initiatives must show a return

otherwise the effort goes waste.

Knowledge creation practices are significantly

related to organizational improvement while

knowledge acquisition practices are positively related

to organizational performance (Seleim and Khalil,

2007). Zack et al. (2009) found that KM practices are

related to measures of organizational performance. In

other words, knowledge practices of creation,

transfer, storage, application and evaluation will

influence organizational performance.

According to Lee and Choi (2003), the support of

IT is essential for carrying out KM activities. Wang

et al. (2007) found that IT support of KM indirectly

benefits manufacturing organizations resulting in

enhanced employee productivity, customer

satisfaction, improved product and service quality,

reduced duplication of efforts and better cooperation.

Chen et al. (2011) also found support for KM

technology positively effecting KM performance.

Thus, it appears logical to believe that a good IT

infrastructure for KM may influence performance.

Culture (underlying beliefs, values and behaviors)

is regarded as one of the most important factors that

impact KM and the outcomes from its use (Alavi and

Leidner, 2001). According to Chang and Chuang

(2011) culture is the most important factor for

successful KM. Thus, positive corporate culture is

expected to enhance organizational performance.

Leadership is an important construct in driving the

success of any organizational initiative. Given the

low awareness levels and maturity of KM within most

organizations, the importance is leadership is even

much more. Anantatmula and Kanungo (2010) found

top management support is most crucial to build a

successful KM initiative as it ensures strategic focus.

Thus, knowledge-oriented leadership will have a

positive impact on organizational performance.

Organizational structure within an organization

may encourage or inhibit knowledge creation, sharing

and application. Mills and Smith (2011) in a survey

involving managers in Jamaica showed that only

organizational structure had a significant impact on

organizational performance. Further, Chen et al.

(2011) found that centralization has a negative impact

on KM performance. Thus, it would be appropriate to

believe that structure will impact organizational

performance.

Hiebler (1996) believes that organizations that can

create and use a set of KM measures tied to financial

results seem to come out ahead in the long run. KM

can impact things like recruitment and retention,

response time for problem solving, customer

satisfaction and avoidance of problems. In addition to

hard numbers success can also be represented in the

form of ‘soft’ benefits such as anecdotes and success

stories (Smith and McKeen, 2004). Rao (2005)

considers five types of metrics which would help

assess the level of KM implementation. These are: 1)

technology metrics 2) process metrics 3) knowledge

metrics 4) employee metrics and 5) business metrics.

In this study statements related to organizational

performance (OP) include non-financial measures

while those of financial performance (FP) include

financial measures. We use the above argument to

postulate that KM induced organizational

performance improvements will improve financial

performance.

Thus, we hypothesize:

H1: KMPD has a positive impact on OP

H2: KMIE positively influences OP

H3: LKM has a positive impact on OP

H4: SKM positively influences OP

H5: CKM positively impacts OP

H6: TKM has a positive impact on OP

H7: Organizational Performance impacts FP

3 RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

Majority of the prior studies on linking KM to

organizational performance have been either done in

public sector or focused on developed countries

(Zhou, 2004; Taylor and Wright, 2004; Park, 2007;

Cong et al., 2007; Goel et al., 2010; Evoy et al., 2019).

Little is known about the impact of KM in developing

and emerging economies. Perhaps the most

significant gap in the literature is the lack of large-

scale empirical studies to link KM to organizational

performance in private sector organisations in India.

The objectives of the study are to:

1. Propose a research model to identify the factors

relevant for KM.

2. Determine the impact of these factors on enhancing

performance in organizations.

Knowledge Management and Its Impact on Organizational Performance in the Private Sector in India

429

4 METHODOLOGY

To meet the first objective, a review of literature was

conducted across multiple research databases with

keywords like “KM impact assessment”, “KM and

performance”, “KM in India”. This process resulted

in several studies, findings of which were synthesized

in the form of broad themes like KM factors, Impact

of KM on performance. Qualitative data collection

techniques like Focus Group Discussion (FGD) and

personal interview was used to explore and

investigate the themes. An FGD guide and an

interview template was prepared for this purpose.

Open ended questions were used for FGD while one

semi-structured interview was conducted with a

senior representative from a private sector

organization in insurance industry. The FGD was

conducted with four representatives from private

sector organizations in manufacturing, information

technology, telecommunications and power

generation. Content analysis of transcripts was done

to identify several themes which were subsequently

cross checked with literature. This resulted in the

identification of factors and associated items relevant

for KM. A web-based questionnaire was designed

with 50 statements. Before launching the survey, the

instrument was shown to two KM experts who were

spearheading the KM initiative in their organizations.

This study employs survey methodology to gather

primary data for meeting the second objective.

Convenience sampling was used to select the

respondents. Majority of the respondents were

reached through the personal networks of the

researchers. Because of these efforts 127 respondents

from private sector in India filled this questionnaire.

Adaptation of eight items for Knowledge

Management Planning and Design (KMPD), 11 for

Knowledge Management Implementation and

Evaluation (KMIE), six for Technology in

Knowledge Management (TKM), six for Culture in

Knowledge Management (CKM), five for Leadership

in Knowledge Management (LKM), four Structure in

Knowledge Management (SKM), seven for

Organization Performance and three for financial

performance come from earlier studies as discussed

in the review of literature section. Items were

measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1

= Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree.

The study employs partial least squares (PLS) to

analyse the research model and seven hypotheses.

The reason for using variance based PLS is twofold;

firstly, it is an SEM technique which estimates the

measurement and structural model simultaneously

and secondly, it imposes less restrictions on

assumptions about distribution of data,

multicollinearity and sample size. SmartPLS 3.0 was

used for this purpose. As a first step, PLS algorithm

is used to estimate the measurement model to assess

the reliability and validity of the theoretical

constructs. Estimation of the structural model

examines the relationships defined as part of the

hypotheses in the research model.

5 FINDINGS OF THE STUDY

5.1 Research Model

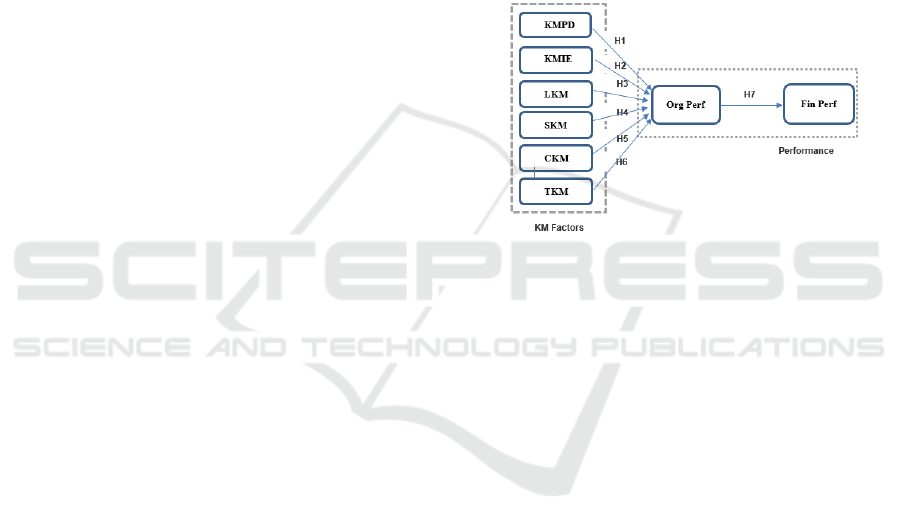

Figure 1: Research Model.

5.2 Measurement Model

The measurement model was assessed in terms of

internal consistency, composite reliability, average

variance extracted and convergent and discriminant

validity.

As per Fornell and Larker (1981), convergent

validity of the scales is based on the fulfilment of

three criteria (1) all item loadings should exceed 0.65

(2) composite reliabilities (CR) should exceed 0.8 and

(3) the average variance extracted (AVE) for each

construct should exceed 0.5. As evident from Table

1, all item loadings are greater than the threshold of

0.65, the CR values are greater than 0.8 and the AVE

ranges from 0.543 to 0.810. Thus, all the three

conditions for convergent validity are met.

For discriminant validity, the square root of the

AVE for each construct must be higher than the

correlation coefficient with other constructs (Fornell

and Larcker, 1981; Liao et al., 2006). As shown in

Table 1, the condition for discriminant validity is

satisfied as the square root of the AVE for each

construct is greater than the estimates of the inter-

correlation between the latent constructs.

KMIS 2019 - 11th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

430

Table 1: Convergent and Discriminant Validity.

Cronbach

Alpha

Range of

Loadings

Composite

Reliability

AVE

CKM

Fin

Perf

KMIE

LKM

Org

perf

KMPD

SKM

TKM

CKM

0.820

0.718-0.808

0.874

0.582

0.763

*

Fin

Perf

0.883

0.884-0.915

0.927

0.810

0.420

0.900

*

KMIE

0.732

0.791-0.824

0.848

0.651

0.655

0.525

0.807

*

LKM

0.844

0.739-0.830

0.889

0.615

0.731

0.566

0.657

0.784

*

Org

perf

0.896

0.708-0.842

0.918

0.617

0.667

0.733

0.721

0.759

0.785

*

KMPD

0.797

0.801-0.872

0.881

0.712

0.705

0.610

0.744

0.738

0.750

0.844

*

SKM

0.719

0.679-0.790

0.826

0.543

0.687

0.475

0.706

0.745

0.702

0.705

0.73

7*

TKM

0.759

0.716-0.793

0.847

0.580

0.595

0.509

0.644

0.694

0.698

0.689

0.60

7

0.76

2*

* Diagonal values are squared roots of AVE; off-diagonal values are the estimates of the inter-correlation between the latent constructs

Table 2: Structural Model.

Path (Hypothesis)

Original

Sample (O)

Sample

Mean (M)

Standard

Deviation

(STDEV)

T Statistics

(|O/STDEV|)

P Values

Supported/Not

Supported

KMPD -> Org perf (H1)

0.192

0.194

0.085

2.274

0.023**

Supported

KMIE -> Org perf (H2)

0.200

0.195

0.111

1.793

0.073***

Supported

LKM -> Org perf (H3)

0.268

0.273

0.098

2.733

0.006*

Supported

SKM -> Org perf (H4)

0.098

0.103

0.107

0.912

0.362

Not Supported

CKM -> Org perf (H5)

0.037

0.031

0.078

0.474

0.635

Not Supported

TKM -> Org perf (H6)

0.170

0.170

0.082

2.061

0.039**

Supported

Org perf -> Fin Perf (H7)

0.733

0.733

0.049

14.818

0.000*

Supported

* significant at 1 percent; ** significant at 5 percent; *** significant at 10 percent

5.3 Structural Model

After analysing the measurement model, the next step

is to test the relationships between constructs as

depicted in the research model in the form of

hypotheses H1 to H7. For structural model analysis,

bootstrapping (500 sub-samples) technique is used as

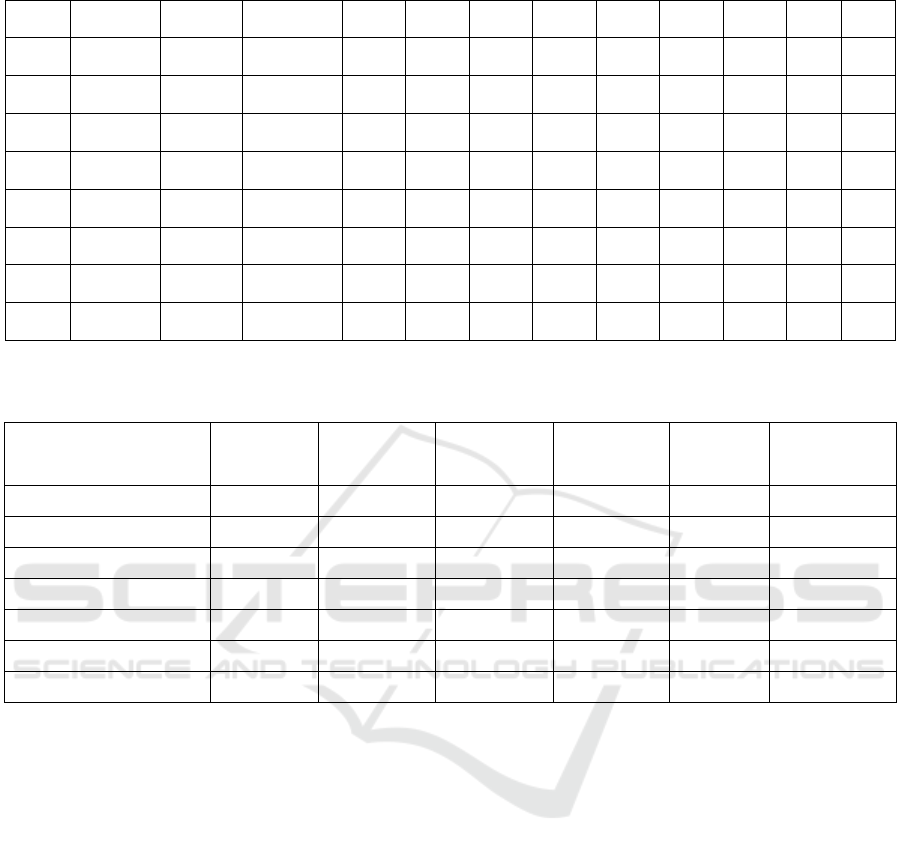

suggested by Chin (1998). Figure 2 displays the

results of the structural model showing standard

errors, t-values, path coefficients and the significance

value.

The results of the structural model as summarized

in Table 2 offer support for hypotheses H1, H2, H3,

H6 and H7. Hypotheses H4 and H5 are not supported

although their path coefficient is in the desired

positive direction. H1 and H2 predicts a positive and

significant impact from KMPD and KMIE on

Organizational Performance. The more an

organisational performance. Similar results are found

for the construct LKM (H3), which also has a positive

and significant effect on organisational performance.

With respect to H4 and H5 it is seen that both

SKM and CKM practices influence organizational

performance positively, but the impact is

insignificant. Therefore, H4 and H5 are rejected.

Considering the postulated link between TKM

and organisational performance, it is found that TKM

has a positive and significant effect.

As per (Ringle et al., 2012), path significance

alone is not the only indicator of importance, the

effect size f squared (Cohen, 1988) of each

relationship and relative prediction relevance q

square (Hair et al., 2014) for each of the endogenous

constructs was assessed. Values of 0.02, 0.15 and

0.35 denote a small, medium or large f square or q

square effect size respectively. It is evident from

Table 3 that for all significant relationships, the f

square effect size is medium while its small for the

insignificant ones. Thus, for all significant

Knowledge Management and Its Impact on Organizational Performance in the Private Sector in India

431

relationships it can be inferred that the effect of

omitting a predictor of an endogenous constructs in

terms of the change in the R square value of the

construct (organisational performance) would be

medium.

The predictive relevance of structural model was

tested by calculating cross-validated redundancy (Q

square). Using blindfolding technique. The smaller

the difference between the predicted and original

value, higher is the value of Q2 and thus higher is the

predictive accuracy of the model. The value of Q

square greater than zero indicates satisfactory

accuracy. In our case, the values of Q square equals

0.395 for Organizational Performance.

Finally, results also confirm the impact of

organisational performance on financial performance

(H7). Overall, the structural model explains 70.4

percent of the variance in organizational performance

and 53.8 percent of the variance in financial

performance.

Figure 2: Structural Model - Path Coefficients and P-values.

As per (Ringle et al., 2012), path significance alone is

not the only indicator of importance, the effect size f

squared (Cohen, 1988) of each relationship and

relative prediction relevance q square (Hair et al.,

2014) for each of the endogenous constructs was

assessed. Values of 0.02, 0.15 and 0.35 denote a

small, medium or large f square or q square effect size

respectively. It is evident from Table 3 that for all

significant relationships, the f square effect size is

medium while its small for the insignificant ones.

Thus, for all significant relationships it can be

inferred that the effect of omitting a predictor of an

endogenous constructs in terms of the change in the

R square value of the construct (organisational

performance) would be medium. The predictive

relevance of structural model was tested by

calculating cross-validated redundancy (Q square).

Using blindfolding technique. The smaller the

difference between the predicted and original value,

higher is the value of Q2 and thus higher is the

predictive accuracy of the model. The value of Q

square greater than zero indicates satisfactory

accuracy. In our case, the values of Q square equals

0.395 for Organizational Performance.

Table 3: f² and q² values for the endogenous variable

Organizational Performance.

Path

R

Square

f

Square

Q

square

q

square

All

construct

s included

0.704

0.395

CKM

excluded

CKM to

Org Perf

0.002

0.394

0.002

KMIE

excluded

KMIE to

Org Perf

0.048

0.394

0.002

KMPD

excluded

KMPD

to Org

Perf

0.037

0.390

0.008

LKM

excluded

LKM to

Org Perf

0.071

0.385

0.017

SKM

excluded

SKM to

Org Perf

0.011

0.394

0.002

TKM

excluded

TKM to

Org Perf

0.042

0.389

0.010

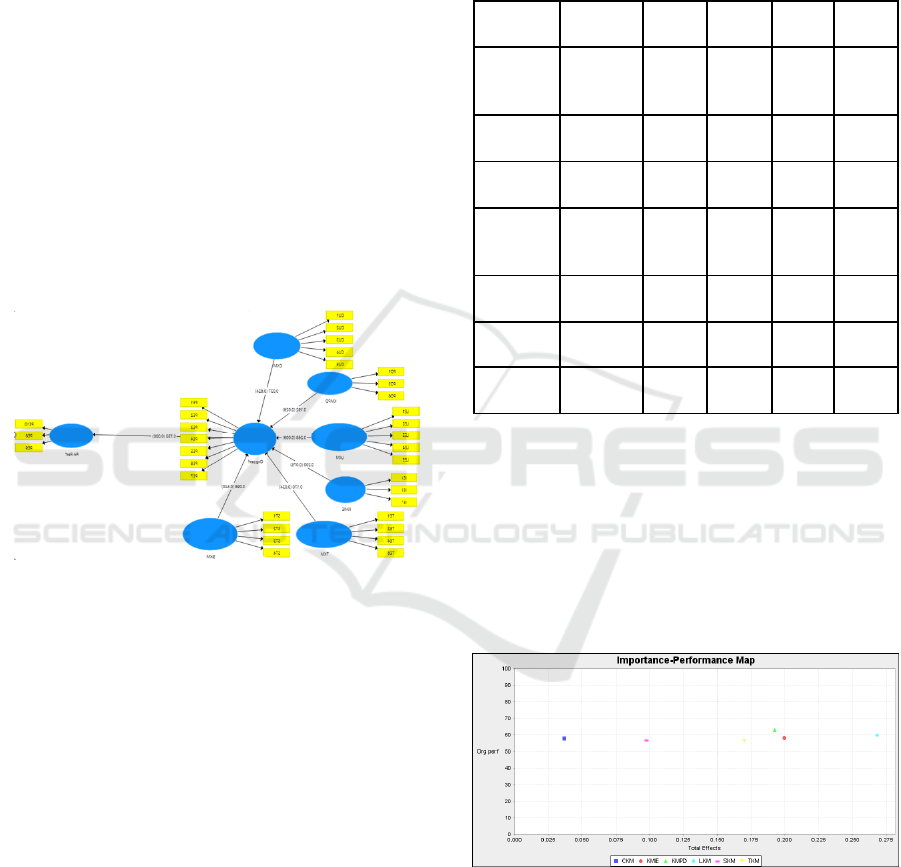

Next, the importance-performance map analysis

(IPMA) was carried out to the results of PLS-SEM by

also taking the performance of each construct into

account. Here the target variable considered was

organizational performance. The objective was to

primarily identify those constructs which exhibit a

large importance regarding their explanation of

organisational performance but, at the same time,

have a relatively low performance.

Figure 3: The Importance-Performance Matrix for

Organizational Performance.

In order of importance, LKM is the most important

followed by KMIE, KMPD, TKM, SKM and CKM

respectively. Further, in terms of performance, all the

constructs have more or less the same performance score

(around 60) on a scale from 0 to 100. In terms of importance

effect (total effect), LKM is the most relevant group

KMIS 2019 - 11th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

432

followed by the KMIE, KMPD, TKM group. CKM and

SKM can be treated as a relatively less important group.

6 CONCLUSIONS AND

RECOMMENDATIONS

We found that out of the seven hypotheses, five were

supported. KM processes (KMPD and KMIE) were

found to positively and significantly influence

organisational performance.

With respect to leadership, we found that KM

leadership is an important construct which influence

organisational performance significantly. Similar

findings have been reported by earlier researches.

Anantatmula and Kanungo (2010) found top

management support is most crucial to build a

successful KM initiative as it ensures strategic focus.

It was found that technology infrastructure has a

statistically significant influence on organisational

performance. Thereby this finding corroborates the

findings of earlier studies about the importance of

leadership for enhancing organisational performance

(Lee and Choi, 2003; Chen et al., 2011)

However, we could not find support for two of our

hypotheses related to KM structure (H4) and culture

(H5) and the target construct organisational

performance. We believe that a reasonable

explanation for this observation is that KM structure

and culture in private sector organization is fairy well

developed and respondents may have perceived this

as a relatively less important construct impacting

organisational performance.

Considering that organisational performance is

influenced by so many factors other than KM, it

seems that the obtained results (explained variance of

70.4 percent) justify the strong impact of KM on

organisational performance. Further, KM induced

organisational performance is found to explain 53.8

percent of variation in financial performance. This

means that KM constructs act as appropriate

antecedents to organisational performance. One of the

implications of the findings could be that KM does

not directly influence financial performance but

routes it through organisational performance. Thus,

testing the mediator role of organizational

performance can be an area of future study.

IPMA analysis of Indian private sector data

reveals that the effect of the various KM constructs

on organisational performance can be grouped into

three. The highest important construct is leadership,

followed by planning, implementation and usage of

technology. The last group comprises of culture and

structure. One of the plausible reasons could be that

private sector enterprises assign more importance on

leadership and policy & strategy. With respect to

culture and structure, since private sector companies

are dynamic workplaces which are constantly

evolving, creation and exchange of knowledge is a

way of life. Private sector organizations have taken

better measures to reduce hierarchies and enhance

streamline flow of knowledge. Since conducive

structure and culture are by composition ingrained in

private sector organizations, their importance for KM

is perceived as relatively lower as compared to other

constructs. Singh and Sharma (2011) found

organizational culture to be positively and highly

correlated with KM in Indian private sector. Thus,

one of the recommendations which emerge from the

above discussion is that the buy-in of the top

management for KM success is most critical. Further,

the existence of the formal KM planning,

implementation and evaluation is important. To start

with the initiative, private sector organizations can

prepare a business case to align the initiative to

address critical real-world business problems.

Further, identifying a KM team, defining roles and

responsibilities including subject matter experts

should be an integral part of the KM planning

process.

REFERENCES

Alavi, M., & Leidner, D. 2001. Knowledge management and

knowledge management systems: conceptual

foundations and research issues. MIS Quarterly, 25(1),

107-136.

Anantamula, V. S., & Kanungo, S. 2010. Modeling enablers

for successful KM implementation. Journal of

Knowledge Management, 14(1), 100-113

Aujirapongpan, S., Vadhanasindhu, P., Chandrachai, A. &

Cooparat, P. (2010). Indicators of knowledge

management capability for KM effectiveness. VINE,

40(2), 183 – 203.

Bierly, P., & Daly, P. 2002. Aligning human resource

management practices and knowledge strategies. In C.

Choo, & N. Bontis (Eds.), The strategic management of

intellectual capital and organizational knowledge (pp.

277–295). New York: Oxford University Press.

Chang, T. C. & Chuang, S. H. 2011. Performance

Implications of Knowledge Management Process:

Examining the Roles of Infrastructure Capability and

Business Strategy, Expert Systems with Applications, 28,

6170-6178.

Chong, S. C. 2006. KM critical success factors: A

comparison of perceived importance versus

implementation in Malaysian ICT companies, The

Learning Organization, 13(3), 230 – 256.

Knowledge Management and Its Impact on Organizational Performance in the Private Sector in India

433

Chong, S. C. & Choi, Y. S. 2005. Critical Factors in the

Successful Implementation of Knowledge Management,

Journal of Knowledge Management Practice, 6.

Chen, W., Elnaghi, M. & Hatzakis, T. 2011. Investigating

knowledge management factors affecting Chinese ICT

firms performance: An integrated KM framework.

Information Systems Management, 28(1), 19-29.

Chin, W. W. 1998. The partial least squares approach to

structural equation modeling, Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates, Mahwah, New Jersey

Cohen J. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral

Sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Cong, X., Li-Hua, R. and Stonehouse G. 2007. Knowledge

management in the Chinese public sector: empirical

investigation, Journal of Technology Management in

China, 2(3), 250-263

Donate, M. J. & Pablo, J. D. S. 2015. The role of knowledge-

oriented leadership in knowledge management practices

and innovation, Journal of Business Research, 68(2),

360-370

Evoy, P. J. M., Mohamed, A.F.R. & Arisha, A. 2019. The

effectiveness of knowledge management in the public

sector, Knowledge Management Research & Practice,

17(1), 39-51.

Fornell, C. & Larker, D. F. 1981. Evaluating Structural

Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and

Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research,

18(1), 39-50.

Goel, A. K., Sharma, G. R. & Rastogi, R. (2010), Knowledge

Management implementation in NTPC: an Indian PSU,

Management Decision, 48(3), 383-395.

Gold, A.H., Malhotra, A., Segars, A.H. 2001. Knowledge

Management: an organizational capabilities perspective,

Journal of Management Information Systems,18(1), 185-

214.

Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G.

2014. Partial least squares structural equation modeling

(PLS-SEM). European Business Review, 26, 106–121.

Hiebler, R. 1996. Benchmarking Knowledge Management,

Strategy and Leadership, 24(2), 22-29.

Lee, H. and Choi., B. 2003. Knowledge Management

enablers, processes and organizational performance: an

integrative view and empirical examination, Journal of

Management Information System, 20(1), 179-228.

Leonard-Barton, D. 1995. Wellsprings of Knowledge:

Building and Sustaining the Source of Innovation,

Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

Liao, C., Palvia, P., & Lin, H-N. 2006. The Roles of Habit

and Web Site Quality in E-Commerce, International

Journal of Information Management, 26(6), 469-483.

Mills, A. & Smith, T. 2011. Knowledge Management and

Organizational Performance: A Decomposed View,

Journal of Knowledge Management, 15(1), 156-171.

Mom, T.J.M., Van Den Bosch, F.A.J. & Volberda, H. W.

2007. Investing managers’ exploration and exploitation

activities: the influence of top-down, bottom-up and

horizontal knowledge flows, Journal of Management

Studies, 44, 910-931.

Nevis, E., DiBella, A., Gould, J. 1998. Understanding

organizations as Learning Systems, https://

sloanreview.mit.edu/article/understanding-organizations

-as-learning-systems/ accessed on June 05, 2019

O’Dell, C., Hasanali, F., Hubert, C., Lopez, K. Odem, P. &

Raybourn, C. 2004. Successful KM Implementations: A

Study of Best Practice Organizations, Handbook of

Knowledge Management 2 – Knowledge Directions, pp.

411-441.

Park, S. C. 2007. The comparison of knowledge management

practices between public and private organizations: An

exploratory study, Dissertation, The Pennsylvania State

University.

Rao, M. 2005. Overview of KM Tools, in Knowledge

Management Tools and Techniques: Practitioners and

Experts Evaluate KM Solutions, Elsevier Butterworth-

Heinemann; Oxford UK.

Ringle, C.M., Sarstedt, M., Straub, D.W. 2012. A critical

look at the use of PLS-SEM in MIS quarterly, MIS

Quarterly 36 (1), 3-14.

Sarvary, M. 1999. Knowledge management and competition

in the service industry, California Management Review,

41(2), 95-107.

Seleim, A. & Khalil, O. 2007. Knowledge management and

organizational performance in the Egyptian software

firms, International Journal of Knowledge Management,

3(4), 37-66.

Singh, A. & Soltani, E. 2010. Knowledge management

practices in Indian information technology companies,

Total Quality Management, 21(2), 145-157.

Singh, A. K. & Sharma, V. 2011. Knowledge management

antecedents and its Impact on Employee Satisfaction – A

Study on Indian Telecommunication Industries, The

Learning Organization, 18(2), 115-130.

Smith, H. A. & McKeen, J. D. 2004. The Knowledge Chain

Model: Activities for Competiveness, Handbook of

Knowledge Management 2 – Knowledge Directions, pp.

395-410.

Sveiby, K. 2001. What is Knowledge Management?

available at https://www.sveiby.com/files/pdf/

whatisknowledgemanagement.pdf accessed on June 01,

2019.

Taylor, W. A. & Wright, G. H. 2004. Organizational

Readiness for Successful Knowledge Sharing:

Challenges for Public Sector Managers, Information

Resources Management Journal, 17(2), 22-37.

Wang, E., Klein, G. & Jiang, J. J. 2007. IT support in

manufacturing firms for a knowledge management

dynamic capability link to performance, International

Journal of Production Research, 45(11), 2419-2434.

Wong, K. Y. and Aspinwall, E. 2004. Knowledge

Management Implementation Framework: A Review,

Knowledge and Process Management, 11(2), 93-104.

Zack, M., McKeen, J. and Singh, S. 2009. Knowledge

Management and Organizational Performance: An

Exploratory Analysis, Journal of Knowledge

Management, 13(6), 392-409.

Zhou, A. Z. 2004. Managing Knowledge Strategically: A

Comparison of Managers' Perceptions between the

Private and Public Sector in Australia, Journal of

Information & Knowledge Management, 3(3), 213-222.

KMIS 2019 - 11th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

434