WHEN BUSINESS MODELS GO BAD: THE MUSIC INDUSTRY’S

FUTURE

Erik Wilde

Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH)

Z

¨

urich, Switzerland

Jacqueline Schwerzmann

Swiss National Television (SFDRS)

Z

¨

urich, Switzerland

Keywords:

File Sharing, P2P, RIAA, IFPI, DMCA

Abstract:

The music industry is an interesting example for how business models from the pre-Internet area can get into

trouble in the new Internet-based economy. Since 2000, the music industry has suffered declining sales, and

very often this is attributed to the advent of the Internet-based peer-to-peer file sharing programs. We argue

that this explanation is only one of several possible explanations, and that the general decrease in the economic

indicators is a more reasonable way to explain the declining sales.

Whatever the reason for the declining sales may be, the question remains what the music industry could

and should do to stop the decline in revenue. The current strategy of the music industry is centered around

protecting their traditional business model through technical measures and in parallel working towards legally

protecting the technical measures. It remains to be seen whether this approach is successful, and whether the

resulting landscape of tightly controlled digital content distribution is technically feasible and accepted by the

consumers. We argue that the search for new business models is the better way to go, even though it may take

some time and effort to identify these business models.

1 INTRODUCTION

Since its invention in the early 1990’s, the Web has

changed many things. It is the first global informa-

tion system with a user base counting in hundreds

of millions, and in many industrialized countries, the

user base covers 50% of the population or more. This

means that the Web is a medium that can fundamen-

tally change businesses, in particular when the busi-

nesses are dealing with immaterial goods (i.e., ideally

suited for electronic distribution) rather than physical

products. Among others, the music industry has been

seriously affected by the Web, and in this paper we de-

scribe the observable facts, their interpretation of the

music industry, some interesting alternative interpre-

tations, and conclude with some remarks about more

appropriate and promising ways to act and react in a

rapidly changing world.

A detailed and insightful study of the music indus-

try has recently been published by (Phillips and John-

son, 2004). For the purpose of this paper, the fol-

lowing players and concepts are most important: The

Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) is

the biggest national music industry association, and

thus the most important player in the field of mu-

sic industry associations. However, the national bod-

ies in this field are united under the roof of the In-

ternational Federation of the Phonographic Industry

(IFPI), which is the world-wide organization of cur-

rently 46 national members.

With regard to legislatory action, the 1998 U.S.

Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) has been

the most thoroughly discussed law for regulating in-

tellectual property rights and their technical imple-

mentation. The DMCA prohibits the circumvention

of technical measures intended to protect the rights of

copyright owners in addition to the legal protection of

the content itself. Furthermore, removal or alteration

of copyright management information are prohibited.

However, the DMCA has not been an initiative of

U.S. legislation. It simply is a national implemen-

tation of the international WIPO Copyright Treaty

(WCT), which in 1996 had been created by the World

Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), a UN-

funded organization. Other countries or political enti-

ties are following the path of the DMCA, for example

in 2001 the EU published the EU Copyright Direc-

tive, and EU countries are now transforming the EU

directive into national law, for example Germany in

2003.

48

Wilde E. and Schwerzmann J. (2004).

WHEN BUSINESS MODELS GO BAD: THE MUSIC INDUSTRY’S FUTURE.

In Proceedings of the First International Conference on E-Business and Telecommunication Networks, pages 48-54

DOI: 10.5220/0001397800480054

Copyright

c

SciTePress

2 HISTORIC PERSPECTIVE

The invention of new devices or ways of recording,

storing, playing, and distributing media has always

been the source of huge changes in the media market.

For the music market, inventions such as the radio,

the phonograph, the magnetic tape, the compact cas-

sette, the Compact Disc (CD), and then even digital

recording media such as Digital Audio Tape (DAT) or

the MiniDisc have been turning points in the way the

industry worked. Whenever new inventions changed

the landscape of the music industry, many companies

claimed that these inventions would ruin their busi-

ness. For the most inflexible companies, this some-

times turned out to be true, but the majority of com-

panies managed to adapt to the new reality and sur-

vived, and often even thrived because of new business

opportunities that had opened up.

For a very long time now, since the invention of

the phonograph in the late 19th century, the music in-

dustry was centered around physical products, even

though the actual products changed. For the first time

now, the industry faces a shift away from physical

products, since computer networks and efficient au-

dio compression methods have enabled users to treat

music as simple data. And since data is most powerful

when it is as loosely coupled with physical media as

possible, people are doing exactly this, copying their

music from one CD to another, from a CD to their

computer or their portable audio device, or vice versa.

Users are expecting this kind of freedom because

they are used to so-called fair use. Fair use is what

enables users to use copyrighted material to a certain

extent, so that they can create private copies of their

CDs, even give these away to their friends, without

doing anything illegal. Since for a very long time, all

this fair use required the use of blank media (such as

empty cassettes), Europe’s music industry managed

to collect a share from every sold blank media, based

on the assumption that a substantial fraction of them

would be used to record copyrighted material. With

the recent development of treating everything as data,

it becomes difficult to downright impossible to con-

tinue along this road, because blank media are no

longer specific to the media type, and a blank DVD

may be used to record one possibly copyrighted film

or days worth of music.

So the challenge the music industry is facing is that

they are essentially moving away from their niche of a

specialized business in a specialized hardware world,

but are simply becoming content providers. The cur-

rent tactics of the music industry is to protect their

niche through technical and legislative actions, and

the interesting question is whether this will succeed

technically, and whether it will succeed culturally,

when long-standing rights such as the fair use prac-

tice are essentially taken away from the consumers.

3 TECHNICAL DEVELOPMENT

All file sharing tools use Peer to Peer (P2P) tech-

nology, meaning that the actual files are always ex-

changed between individual users. This is a departure

from the more traditional client/server-model, where

service providers offer a particular service (such as

the pages of a Web site), and clients use this service by

connecting to the server. P2P is an architecture where

participants dynamically can be server and/or clients,

which makes the overall architecture much more flex-

ible. Furthermore, for large amounts of data, trans-

ferring them in a grid of cross-connected computers

is much more scalable then a centralized architecture,

where a central server would turn into a bottleneck if

too many clients were using it.

While P2P architectures are still an active field of

research, first approaches and implementations were

available in the early days of the Web. However, it

was not until Napster arrived that P2P became pop-

ular. Napster combined a user-friendly interface de-

sign and a focus on music, which quickly attracted

a large number of users. Before Napster, file sharing

was only practiced in rather small circles of people us-

ing technology that was much less user-friendly. As

a result, the supply of available music was limited.

Napster attracted enough users to make virtually ev-

erything available, which again attracted more users

and thus helped Napster to succeed as it did.

3.1 Centralized P2P Directory

Napster was the first file sharing application that used

the Internet for distributing files. Napster’s approach

was to implement the actual file transmission as a

P2P transaction, but the directory and search services

were hosted centrally. This centralized architecture

made the system an easy target to attack (both techni-

cally and/or legally), and Napster was shut down (by

a court decision made in San Francisco) in 2000.

Since this was the proof that centralized systems

would be the targeted legally, no other centralized sys-

tem or service appeared. Furthermore, P2P technol-

ogy had already advanced past the centralized archi-

tecture and developed new architectures, which did

not have any centralized host.

3.2 Distributed P2P Directory

After Napster’s shutdown, applications such as Kazaa

and Grokster (using FastTrack) and Morpheus (based

on StreamCast and the open Gnutella protocol) ap-

peared, and they are still in use today. These P2P

applications do not have a central host, but instead

continually exchange directory and search informa-

tion. Thus, a dynamic network of participating users

WHEN BUSINESS MODELS GO BAD: THE MUSIC INDUSTRY'S FUTURE

49

is formed, which cannot be easily targeted legally or

technically. A newer application in this area is eDon-

key, which improves the search mechanisms and im-

proves download performance by splitting files into

pieces and distributing the pieces.

However, the recent aggressive RIAA campaign in

the United States proves that given sufficient legisla-

tive support, even systems as volatile and seemingly

anonymous as distributed P2P applications can be tar-

geted legally. The RIAA intercepts protocol messages

from these applications, concludes that a user is ille-

gally sharing copyrighted material, and then uses the

DMCA to force ISPs to disclose the identity of the

individual user. This practice has been rejected by a

D.C. district court order in December 2003, requiring

a formal lawsuit to get the information from the ISPs.

Even though the legal battle will continue, it is clear

that the music industry is targeting users instead of the

makers of P2P software

1

. The weak point that is ex-

ploited by the RIAA is the directory information that

is made available by the P2P clients. To address this

issue, new forms of P2P file sharing have been devel-

oped, which do not require any directory information

to be transmitted over the P2P network at all.

3.3 Directory-less P2P

The BitTorrent application introduced a new concept

into the P2P file sharing world: Directory information

is no longer part of the P2P application, but handled

individually. In practice, BitTorrent is based on Web

servers which list available files, and these lists are

regular Web pages which can be accessed with any

Web browser. As soon as a user selects one of the files

to download, the request is handled by a local Bit-

Torrent client, which starts the download as a highly

optimized P2P activity, thereby sharing the data with

other users downloading this particular file.

The disadvantage of this approach is the fact that

the Web servers again are an easy target for techni-

cal and/or legal measures, but since they do not need

any specialized software, it is rather easy to move the

contents between different servers, and at the time of

writing, there is an ongoing hide-and-seek game be-

tween groups of individuals hosting the Web pages,

and institutions claiming that the Web pages aid the

illegal distribution of copyrighted content.

Another interesting facet of BitTorrent (as well as

some modern applications using the distributed P2P

directory approach) is that the P2P principle is ex-

tended to encompass all users interested in a certain

file. Consequently, if there are 20 users exchanging a

file, it is never completely transmitted from one user

1

In a L.A. court decision from April 2003, it was de-

cided that the P2P itself is not illegal, but the exchange of

copyrighted material using this software could be.

to another user. Instead, every users provides frag-

ments of the file to others, and receives fragments of

the file from others, so that there is no single, eas-

ily identifiable interaction where to users actually ex-

changed a complete file. This makes legislation more

difficult, since it is much harder to identify complete

transactions.

4 ONLINE MUSIC SHARING

STATISTICS

One of the most important tools for carrying opinions

are statistics. Since the music industry’s goal is to in-

fluence legislation, there must be some data support-

ing the claims made by the music industry. History,

as discussed in the previous section, does not pro-

vide any evidence that technological revolutions had

a negative influence on the music industry. The music

industry thus claims that this specific technological

revolution is completely different than the previous

ones, because it enables perfect copies, and facilitates

worldwide distribution for everyone. To back this

claim, the music industry presents statistics, which

are very interesting to look at.

The problem with file sharing is that the evolu-

tion of file sharing tools (as described in Section 3)

has continually reduced the possibility to measure

the number of shared files. In order to overcome

this problem, many statistics presented are based on

highly questionable numbers, which euphemistically

could be described as upper bounds of the (unknown)

real numbers:

• Software downloads: Commercially oriented com-

panies such as Kazaa and Morpheus often report

the number of times a software has been down-

loaded in order to show the popularity of their ser-

vice. Naturally, this number is of some signifi-

cance, again constituting an upper bound of users

(if installation files are not further distributed).

However, the number of actual users heavily de-

pends on the quality of the software (if the soft-

ware is unstable and hard to use, many people will

stop using it) and the utility of using it (many com-

mercial P2P products are notorious for containing

a variety of Adware and Spyware add-ons). Thus,

the number of software downloads may be interest-

ing, but is a number of very low significance when

measuring the usage of a service.

• Shared files: P2P clients using directory informa-

tion make it possible to plug into the P2P network

and get information about the shared files. How-

ever, the number of files shared is no indication of

how many of them are copyrighted material, how

many of them are duplicates, and how many of

ICETE 2004 - GLOBAL COMMUNICATION INFORMATION SYSTEMS AND SERVICES

50

them can be retrieved successfully. Even though

a file is appearing in the directory service does not

mean that is has or will ever be shared. Many will

not be shared because the users have disabled or re-

duced uploading speed, and many others are never

successfully shared because transfers stop before

the complete file is transmitted.

For directory-less P2P clients, it is principally im-

possible to even measure something like the num-

ber of shared files, so for these clients this number

cannot be given or even estimated. To summarize,

the measurement of shared files is a number that

may be interesting (and often is used by commer-

cial P2P software vendors to lure new customers),

but is of very low significance. To make things even

less meaningful, since April 2003 the RIAA has be-

gun to systematically flood various P2P networks

with fake files.

• Sales of recordable media: Since many users

archive media files on digital media (mostly CD-

R, with an increasing share of DVD-R), the sales of

recordable media are taken as a direct measurement

of illegally copied content. The measurements are

based on user polls which in many cases involve a

rather small number of users, so that (1) the signif-

icance of these polls is limited. It is (2) also un-

clear how much of the media being used for music

recording are used for fair use copies of legally ac-

quired music. And it is (3) assumed that each media

that is recorded is counted as a CD that otherwise

would have been bought. This claim seems to be

bold to make.

What makes things even more irritating is that the

music industry receives money for each recordable

media being sold, through long-standing agree-

ments which in the past had been designed to cover

fair use. Since file sharing is not regarded as fair

use, the music industry claims that all the record-

able are filled with illegally acquired content, but

still collects money for the media. And in an effort

to compensate the revenue losses of the last years,

the music industry wants to increase the amount

of money that users pay for each empty record-

able medium, and maybe even introduce charges

on recording equipment.

2

Even though there certainly is some correlation be-

tween file sharing and the measurements presented

above, it is highly questionable whether the methods

employed by the music industry do more than provid-

ing an upper bound (which may be very far away from

the real numbers). The error margins in the individual

statistical numbers are very large and get even larger

when these numbers are used in combination.

2

With the lucrative side-effect that since music is simply

data, every computer is considered to be recording equip-

ment and would thus be an additional source of income.

Even if it were possible to reliably measure the

number of shared files, the simple technique of mul-

tiplying this number with the normal sales prize of

music media is, again euphemistically speaking, an

upper bound of the loss of revenue. The simple rea-

son is that P2P users collect far more music then they

would ever buy. Even though the per capita expendi-

ture for (mainly) immaterial goods is constantly ris-

ing, there is still a limit to how much people are going

to pay for their immaterial possessions (such as music

or literature).

It is interesting to look at some of the numbers pre-

sented by the music industry. These numbers are very

important, because only a negative impact of new

ways to use music enabled by computers and net-

works will convince legislators to change the law in

the favor of content distributors. Legislation always

has been friendly to content distributors (for exam-

ple by expanding the time period for copyright pro-

tection), but some serious statistic sort of justification

is required for changing the law.

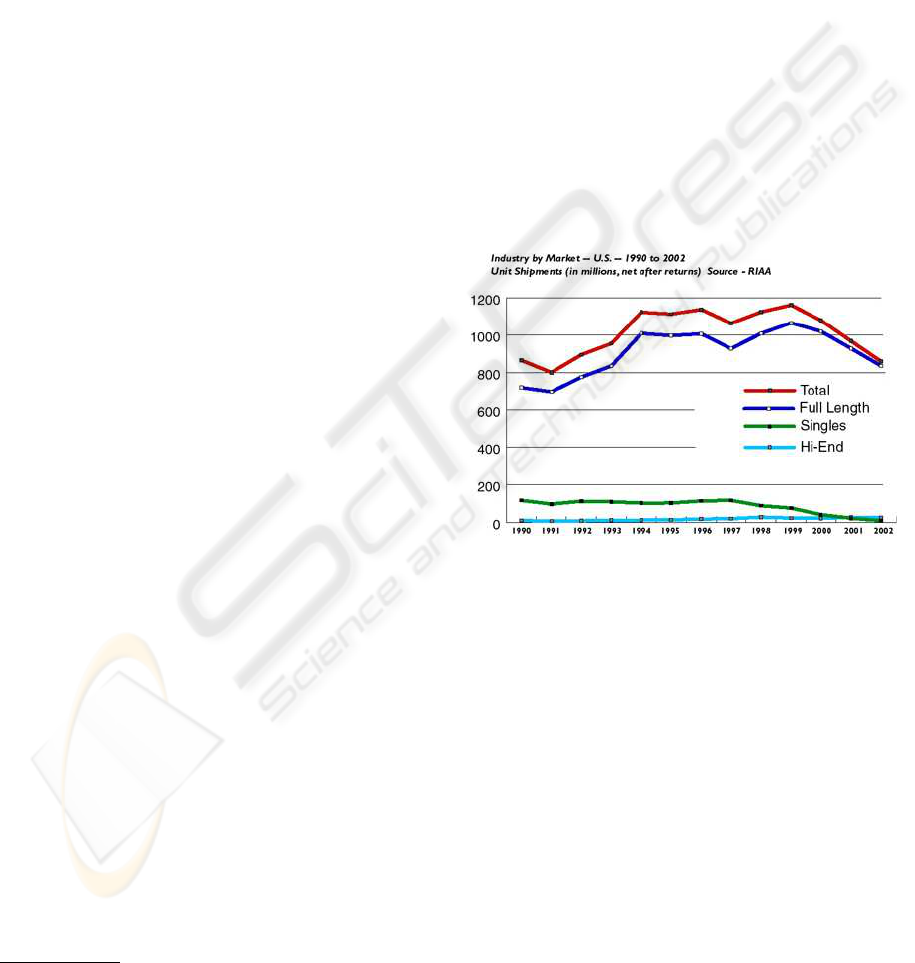

Figure 1: Total Sales U.S. Music Market 1990-2002

In Figure 1 (Figures 1, 2, and 3 are reprinted from

http://www.azoz.com/riaa/news/logic.html), the sales

for different formats of music media is shown. The

“Hi-End” category summarizes music videos, DVD

Music Video, and DVD Audio, but even together with

the single market, which almost disappeared, does

not constitute a relevant segment of the market. The

“Full-length” market comprises vinyl LPs, cassettes,

and CDs, and is the only relevant market. As can be

seen from the figure, the sales numbers have declined

since 1999, and Napster went online in 2000.

Thus, this figure could be used to point out that

“sales declined since the first P2P application became

popular”. This is certainly true and is a correlation

that can be easily observed, but as every statistician

knows, a correlation is not a proof for a cause/effect-

relationship. It may be an indication, and further re-

search or experiments must be conducted to prove or

disprove that there is an cause/effect-relationship. In

WHEN BUSINESS MODELS GO BAD: THE MUSIC INDUSTRY'S FUTURE

51

the case of P2P file sharing, it is hard to make any ad-

ditional analyses, since the invention of P2P file shar-

ing was a singular event and cannot be repeated or

simulated in a controlled environment.

However, in search for reasons for the decline of

sales since 1999, it may be interesting to look at the

general economic development, particularly in case

of a product such as music, which can be considered

a luxury good which people will only spend money

for if they have additional money to spend.

Figure 2: Music Market vs. Dow Jones 1990-2002

Figure 2 shows a comparison of the various full

length media (vinyl LP, cassette, and CD) and the

Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA). The DJIA is

a reliable and generally accepted indicator of the gen-

eral strength of the economy, and suffered a steep de-

cline since the beginning of 2000, when the so-called

Internet Bubble (Perkins and Perkins, 1999) burst.

There is an interesting correlation between the DJIA

and the music industry sales figures in general, and in

particular since 1999.

Looking at this picture, the industry’s claims that

Napster and the following music sharing tools caused

the decline of the music industry sales appear in a dif-

ferent light. To make this alternative interpretation of

the music industry sales even more interesting, Fig-

ure 3 shows the development of the retail prices (sug-

gested list price and actual retail price) between 1997

and 2002.

As can be seen, the retail prices for media increased

constantly over the period of time shown in the fig-

ure. In a slow economy, constantly rising prices for

luxury goods will not help sales. The combination of

the economic situation and the pricing strategy of the

music industry is another way to explain the shrink-

ing sales since 1999. However, this interpretation is

rarely heard or seen, even though it is probably at least

as convincing as the Napster-based explanation.

Figure 3: Average Retail Prices 1997-2002

As a result of this bias towards one interpretation,

politicians tend to favor the music industry in their

legislation. The reason for this is two-fold:

• Statistics are convincing: Only few people in leg-

islation know the fundamental difference between

correlation and cause/effect-relationships, and pre-

sented with the statistics and the Napster-based ex-

planation, they are easily convinced that the music

industry is in danger, and that this is caused by file

sharing.

• Unorganized users: While industry associations

have a lot of money which they can invest in lob-

bying, lawyers, and studies backing their claims,

users do not have a voice that is easily heard or

powerful enough to influence legislation.

Recent legislation such as the DMCA and the EU

Copyright Directive are only implementations of the

WCT, but they are also examples for the extent to

which legislation is influenced by associations. At

present, it seems certain that WCT-influenced laws

will become the normal state of legislation.

It will be interesting to observe the reaction of the

general public when the right for fair use is taken

away from them, at least for certain forms of con-

tent. Even though this is a logical consequence when

moving from buying content by buying some physi-

cal media, to acquiring a license to use some data, the

cultural consequences remain to be seen. For more

than hundred years people have been used to the idea

of “their books” and “their recordings” (and the right

to do with these whatever they like, including copy-

ing, lending, and selling), and it will take some time to

move away from this when eBooks and online music

become the rule rather than the exception.

ICETE 2004 - GLOBAL COMMUNICATION INFORMATION SYSTEMS AND SERVICES

52

5 CONSEQUENCES

The consequences of the Web so far have left the mu-

sic industry rather helpless. The reaction to the new

reality of music as data flowing freely through the

available data channels has been to attempt to stop

this flow through technical measures and legislation.

The alternative, adaptation to the new world, so far

has found amazingly little consideration. In the fol-

lowing two sections we look at these two strategies.

A third way, which would involve more philosophical

than commercial action, is discussed in Section 6, and

it is more a vision and ideal than a realistic course of

action for the current music industry, given its current

focus and way of working.

5.1 Copy Protection

In order to stop or at least reduce the sharing of mu-

sic, various Digital Rights Management (DRM) tech-

nologies have become the focus of attention. Rather

primitive ways are copy-prevention technologies for

CDs as described by (Halderman, 2002). However,

these technologies have been met with some reluc-

tance by users, because many of them mandate violat-

ing the CD standard, so that, technically speaking, the

CDs that users are buying are no longer CDs. Apart

from the principal question whether such a hasty de-

parture from a proven, trusted, and widely accepted

standard such as the CD is a smart thing to do, CD

copy-prevention technologies also reduce the ways in

which a user can use the CDs (after all, this is the one

and only purpose of these technologies).

While the wide-scale distribution of copy-protected

CDs in Europe has been met with only little criticism

and publicity, record companies are still reluctant to

do the same on the American market, because Ameri-

can consumers are generally known to be less tolerant

and complain more when they get what they consider

as an inferior product.

Going beyond simple copy-prevention technolo-

gies for CDs, true DRM technologies including cryp-

tographic methods and licensing, are also slowly

catching on. However, the required infrastructure

for these technologies still make them very heavy-

weight, and from the perspective of a user, they are

much less user-friendly than traditional CDs. (Haber

et al., 2003) argue that even if piracy is identified as

the most important problem for the music industry,

it is questionable whether DRM technologies are the

solution to this problem. They argue that even though

DRM may handle the authorization of copy-protected

content, there will always be a significant amount of

unprotected content available (obtained by dissociat-

ing the content from the DRM information), which

then is distributed to interested consumers.

5.2 Adapting to a New World

While the music industry is mainly concerned with

protecting their traditional sources of income, the

record sales, other companies concentrate on new

business models. Apple’s iTunes was the first online

music distributor to become rather popular, and one

of the reasons is that the concept is modelled around

user-friendliness rather than the goal to protect old

business models. The online distribution on music

still is in its infancy, but it seems to be able to sup-

port a business, given the business is designed to work

within the new world rather than against it. Users are

willing to pay for a real alternative to P2P, if they can

choose among titles of major labels, in user-friendly

formats, without copy protection and for Windows

and Apple platforms. Business models with copy re-

strictions or proprietary formats are less attractive and

less successful.

(Fetscherin, 2003) describes the three major chal-

lenges that content providers are facing in the fu-

ture, which are (1) competing against pirated copies

of their own products, (2) viewing the Internet as a

new distribution channel with fundamentally differ-

ent properties, and (3) learning to observe user accep-

tance of controls and limitations that are imposed on

users. While it seems that the first points are already

included in the music industry’s new business plans,

the third point is largely ignored.

It will be interesting to see how content providers

as well as users adapt to a new world of licensing and

pure data. For example, for an eBook, the perceived

value for a user may be higher or lower than for a tra-

ditional book. For a novel, it may be more convenient

to have a paperback which can be easily handled and

is less fragile than an eBook reader. For a technical

manual, however, it may be very valuable to have it

in eBook form thus providing sophisticated indexing

and searching facilities. For music, there may be sim-

ilar categories, and unless the content providers have

not invested more effort into finding out what people

want and how much they are willing to pay for it, the

adaptation process to the new world of content distri-

bution will remain more difficult than necessary.

6 ALTERNATIVES

While the previous sections described ways how the

music industry could and might be able to make

the transition into a new area, the question remains

whether the whole idea of a completely product-based

view of music is desirable. To phrase this approach

differently: While there maybe companies (even big

ones) that have made their living from viewing and

selling music as a product, it is questionable whether

WHEN BUSINESS MODELS GO BAD: THE MUSIC INDUSTRY'S FUTURE

53

this view of the world should be endorsed by legally

protecting it. Legislators in the U.S. and Europe pro-

tect digital content by enacting stronger intellectual

property law, based on the WIPO treaties. The high

price for a legal framework with such excessive copy-

right restriction will be loss of fair use and anonymity

for the user. Law combined with increasing techni-

cal control shifts the balance between the interests of

users and copyright owners towards the latter.

The WCT and resulting national laws are simply

protecting the interests of traditionally working indus-

tries in a new world, and the price for this often is pri-

vacy. The RIAA’s recent actions against users of file

sharing programs not only have shown that the new

legislation is criminalizing significant fragments of

the population, but also that many privacy issues have

been treated rather lightly when introducing the new

legislation. As an alternative, the Electronic Fron-

tier Foundation (EFF) has suggested to let users of

P2P file sharing services pay a voluntary monthly fee,

which would then be collected and distributed simi-

larly to the European fee on blank media. A similar

approach is letting Internet Service Providers (ISPs)

collect the fee as described by (Sobel, 2003).

As a radical alternative for content providers, the

Creative Commons concepts developed by (Lessig,

1999; Lessig, 2001) is an interesting solution. It is

based on the assumption that all cultural work is inter-

connected and thus cannot be regarded and marketed

as an individual product. This concept is mainly tar-

geted at content providers with no commercial moti-

vation, which want to make sure that their content is

available and can be used by interested parties.

7 CONCLUSIONS

While we argue that the music industry in general

could benefit from concentrating on new business

models rather then protecting the old ones, we do

not deny that commercial music piracy (such as pro-

ducing and selling counterfeit CDs) is a problem and

should be prosecuted. However, the current trend

to criminalize a substantial fraction of the consumer

base is probably counterproductive and will definitely

not help to increase the speed of adaptation to the

new reality of music as data. While large-scale on-

line sharing of copyrighted material is illegal, P2P

applications are not illegal by nature, and could also

serve as a foundation for a new way of making money

with music. Additionally, new studies such as (Ober-

holzer and Strumpf, 2004) indicate that the actual loss

of sales is much smaller than usually claimed.

The current copyright law (before the

WCT/DMCA legislation) is sufficient to protect

copyrighted material, and the attempts to legally pro-

tect the technical protection mechanisms for content

show that the resulting architecture will probably

result in more restrictions for users. The statistics that

are used to convince legislators to accept this kind of

legislation are highly questionable, starting from the

business figures and ending with the user counts and

the concluded loss of revenue. Only the complete

absence of effective user interest lobbying makes the

current legislation possible.

Promising new business models such as iTunes

show that it is possible to make money on the Inter-

net, and that users can be offered a service that is not

overly restrictive but still effective enough to avoid

large-scale exploitation. While we cannot present a

business model that will successfully move the music

industry into the area of the Internet, we are confi-

dent that the current complaints will disappear once

the thinking has moved from protecting the old ways

to discovering and using the new ways.

REFERENCES

Becker, E., Buhse, W., G

¨

unnewig, D., and Rump, N., ed-

itors (2003). Digital Rights Management — Techno-

logical, Economic, Legal and Political Aspects, vol-

ume 2770 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science.

Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

Fetscherin, M. (2003). Evaluating Consumer Acceptance

for Protected Digital Content. In (Becker et al., 2003),

chapter 3.5, pages 301–320.

Haber, S., Horne, B., Pato, J., Sander, T., and Tarjan, R. E.

(2003). If Piracy Is the Problem, Is DRM the Answer?

In (Becker et al., 2003), chapter 2.8, pages 224–233.

Halderman, J. A. (2002). Evaluating New Copy-Prevention

Techniques for Audio CDs. In Proceedings of the

2002 ACM Workshop on Digital Rights Management,

Washington, D.C.

Lessig, L. (1999). Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace.

Basic Books, New York.

Lessig, L. (2001). The Future of Ideas. Vintage Books,

New York.

Oberholzer, F. and Strumpf, K. (2004). The Effect of

File Sharing on Record Sales: An Empirical Analy-

sis. Technical report, University of North Carolina,

Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Perkins, A. B. and Perkins, M. C. (1999). The Internet Bub-

ble. HarperBusiness, San Francisco, California.

Phillips, R. J. and Johnson, R. D. (2004). The Music

Industry. In Bowmaker, S., editor, Economics Un-

cut: A Complete Guide to Life, Death, and Misadven-

ture. Edward Elgar Publishing, Northampton, Mas-

sachusetts.

Sobel, L. S. (2003). DRM as an Enabler of Business Mod-

els: ISPs as Digital Retailers. Berkeley Technology

Law Journal, 18(2).

ICETE 2004 - GLOBAL COMMUNICATION INFORMATION SYSTEMS AND SERVICES

54