ON INFORMATION SECURITY GUIDELINES FOR

SMALL/MEDIUM ENTERPRISES

David Chapman

Chapman Hamer Limited, Hollybrook, Church Street, Kempsey, Worcester, England

Leon Smalov

School of Mathematical & Informations Sciences, Coventry University, Priory Street, Coventry, England

Keywords: Small- Medium Enterprises, Information Security Awareness, Standards

Abstract: The adoption rate of Internet-based technologies by

United Kingdom (UK) Small and Medium Enterprises

(SMEs) is regularly surveyed by the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI). Over several decades

information security has evolved from early work such as the Bell La Padula (BLP) model toward widely

disseminated Information Security Guidelines containing comprehensive and detailed advice. The

overwhelming volume and level-of-detail provided often fails to address the information security

requirements of SMEs. SMEs typically fail to implement effective Internet strategies due to lack of

information security awareness, lack of technical skills and inadequate financial resources. Awareness of

information security issues among SMEs is poor. The European Union supported ISA-EUNET Consortium

has developed a set of best practices to support SMEs. We present a sample mapping of the Computer

Security Expert Assist Team (CSEAT) Information Security Review Areas onto the Alliance for Electronic

Business (AEB) web security guidelines as an example of a possible roadmap approach for SMEs to gain

information security awareness.

1 INTRODUCTION

The United Kingdom (UK) Department of Trade and

Industry [DTI] conduct a series of International

Benchmarking Studies to measure the UK’s progress

towards the Information Age (“2001 International

Benchmarking Study”, 2001). The study assesses

the extent to which UK businesses are using

Information and Communication Technologies

(ICTs) within their operations and compares UK

usage with that of Australia, Canada, France,

Germany, Italy, Japan, the Republic of Ireland,

Sweden and the United States of America.

In the countries studied, the proportion of

busi

nesses

with access to the Internet is greater than

90%, whilst in the UK it is around 94%. Over 80%

of UK businesses now have a web site giving the

UK and Sweden joint highest penetration rates. 1.9

million UK SMEs, defined as a business with less

than 250 employees, are now online, well ahead of

UK Government targets.

The recent growth in the number of businesses

t

radi

ng online has been among micro businesses (up

to 10 employees), whilst in small and medium-sized

bands it has fallen slightly and in the large band it

remains unchanged. The (“2001 International

Benchmarking Study”, 2001, p.4 ) defines a business

as trading online “if it both 1) orders online or

allows its customers to do so and 2) makes payments

online or allows its customers to do so”.

Further research undertaken by the DTI as part

of t

he study

revealed that UK businesses, in

common with their US and Canadian counterparts

have expressed concerns about confidentiality and

fraud. Despite these issues, there are high-levels of

Internet access amongst SMEs.

Over several decades there has been

considera

ble research a

nd development effort put

into information security. The United States (US)

military funding for computer science has supported

the development of advanced security policy

models. There are a number of classic security

models that describe various protection mechanisms.

Anderson (2001) outlines several of the key security

3

Chapman D. and Smalov L. (2004).

ON INFORMATION SECURITY GUIDELINES FOR SMALL/MEDIUM ENTERPRISES.

In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, pages 3-9

DOI: 10.5220/0002593700030009

Copyright

c

SciTePress

policy models, including the Bell-LaPadula model

(1973), the BIBA policy model, Biba (1975) and

several multilateral security models. The Bell-

LaPadula model enforces confidentiality in a

multilevel secure system. Two key properties are

enforced; no read up and no read down. The BIBA

policy model enforces integrity and ignores

confidentiality. Multilateral security models

outlined by Anderson (2001) include

compartmentation used by the intelligence

community, the Chinese Wall model for preventing

conflicts of interest in professional practice and the

BMA model for information flows permitted by

medical ethics.

These large-scale security policy models have

been primarily of interest to the military, larger

enterprises, members of the information security

community and to security product vendors.

Over time, many information security standards

and guidelines have been proposed and developed,

for example, the “Common Criteria for Information

Security Evaluation” (1999) is used as the basis of

evaluation for security properties of IT products and

systems. Using common criteria enables

comparability between the results of independent

security evaluations. This is achieved by providing

a common set of requirements for the security

functions of IT products and systems and their

assurance mechanisms.

The evaluation process is used to establish a

level of confidence that the product and system

security functions and their assurance mechanisms

will meet the security requirements. This helps

system consumers determine whether the IT product

or system is secure enough for the intended usage

and to decide whether the implicit security risks in

using it are tolerable.

The ISO/IEC 17799 “Information Technology -

Code of Practice for information security

management” (2000) provides recommendations on

information security management to those who are

responsible for initiating, implementing or

maintaining security. It provides a common basis

for developing organisational security standards and

effective security management practice.

Organisations are invited to select recommendations

from the standard and use them in accordance with

applicable laws and regulations.

The code gives detailed recommendations and

objectives on security policy (providing

management direction and support for information

security), organizational security (managing security

within the organization), asset classification and

control (maintaining appropriate protection of

organizational assets), personnel security (reducing

the risks of human error, theft, fraud or misuse of

facilities), physical and environmental security

(preventing unauthorized access, damage and

interference to business premises and information),

communications and operations management

(ensuring the correct and secure operation of

information processing facilities), access control

(controlling access to information), system

development and maintenance (ensuring that

security is built into information systems), business

continuity management (counteracting interruptions

of business activities and protecting critical business

processes from the effects of major failures and

disasters) and compliance – (avoiding breaches of

any criminal and civil law, statutory, regulatory or

contractual).

Over many years security policy models have

been introduced and gradually evolved into detailed

and extensive information security standards,

guidelines and other comprehensively documented

forms of advice.

The maturity of a given organisation’s security

engineering process can be assessed using the

“Systems Security Engineering – Capability

Maturity Model” (1999) (SSE-CMM). The volume

of documentation and advice available may infer

that standards play a key role in information security

management.

However, Siponen (2002) raised several research

questions and asserts that information security

research in general, has focused on technical issues

(such as access control mechanisms). Additionally,

guidelines and maturity models, whilst

comprehensive, tend to be too broad and too deep to

be readily utilised by SMEs. SMEs are major users

of IT yet struggle to adopt it successfully. In later

research (2003) Siponen critically analyses some of

the “normative” information security standards,

including ISO/IEC 17799, “Generally Accepted

Principles and Practices for Securing Information

Technology Systems” (Swanson and Guttman,

1996), (frequently referred to as GASSP) and SSE-

CMM to argue that they do not provide a “silver

bullet”. The author comments for SMEs to use SSE-

CMM “may be totally irrelevant and perhaps even

detrimental”.

SMEs typically fail to implement effective

Internet strategies due to lack of information security

awareness, lack of technical skills and inadequate

financial resources. Awareness of information

security issues among SMEs is generally poor. The

authors believe a systematically developed

‘roadmap’ will enable an SME to map their security

requirements onto a practical and relevant set of

security solutions.

In this paper we present a mapping of the

Computer Security Expert Assist Team [CSEAT]

“Automated Information Security Program Review

Areas” (n.d.), onto the Alliance for Electronic

ICEIS 2004 - INFORMATION SYSTEMS ANALYSIS AND SPECIFICATION

4

Business “[AEB] web security guidelines” (2002) as

an example of a possible roadmap approach assisting

SMEs to gain information security awareness.

2 SME ICT AND INFORMATION

SECURITY ISSUES

There are a number of challenges faced by SMEs

with ICT. In a literature review-based study of the

challenges faced by SMEs in their use of ICT

Chesher and Skok (2000) indicated that

organisations progress through evolutionary phases

in their use of IT. These were identified as 1)

inactive (with no current use of IT), 2) basic (using

word processing and desktop packages), 3)

substantial (with networked PCs and use of several

applications) and 4) sophisticated (the integration of

applications and exploitation of ICT to achieve

service differentiation).

Chesher and Skok (2000) report that SMEs

complain of being unable to fully utilise their ICT

due to a lack of time and lack of resources. Some

SMEs are making greater use of ICT and believe

that they are allocating appropriate resources.

Keeping up-to-date with ICT is not a high priority

for many managers. When focussed, business

oriented events are held that provide an opportunity

to gain practical knowledge in the relevant business

sector they are considered useful. Overall, ICT is

not perceived as providing value for money. The

costs of ICT frequently outweighs its benefits. ICT

does not lead the business forward in areas such as

innovation or research and development. ICT tends

to be focussed on efficiency improvements.

Financial applications are concerned with

bookkeeping rather than financial management and

long-term planning. The greatest potential gains in

using ICT come from improving communications.

Managers frequently seek external assistance to

introduce and develop ICT with suppliers and IT

consultants viewed as the main source of external

advice. Government agencies or trade associations

are not perceived as key sources of help.

Developing effective ICT strategies for SMEs is

not simple, largely because SMEs are not a

homogenous group. It is against the background of

ICT adoption issues that the concerns of information

security and SMEs can be considered.

In “small firms at risk from hackers” (Millar,

n.d.) warns SMEs to wake up to the risks of Internet

fraud and hackers. In a survey of 500 senior

managers it is claimed that 61% of small businesses

had no firewall in place, 76% of firms have some

virus protection installed, 41% of senior

management were not aware of their legal liabilities

with regard to the Internet and their business, only

12% of SMEs were concerned that email was legally

binding and only 10% were concerned about

employee misuse.

3 EXISTING APPROACHES TO

INFORMATION SECURITY

The rapid adoption of Internet-based ICT

technologies has prompted organisations of all sizes

to re-evaluate their approach to information security.

European SMEs also face these challenges.

Spinellis and Gritzalis (1999) describe the European

Union supported ISA-EUNET integrated approach

to computer security technology awareness, support,

education and training aimed at disseminating

security and safety know-how to SMEs.

The ISA-EUNET strategy relies on three main

elements; 1) a TEChnical KNowledge Office

(TEKNO), providing a kernel of scientific and

technical competencies that share software best

practices in security and safety applications; 2)

regional partners that deal directly with target SMEs

through support, training and tutoring and 3) a co-

ordinator that oversees European events, maintains

consortium consistency and enforces contractual

conditions.

At the level of an individual small business

Spinellis, Kokolakis and Gritzalis (1999) have

proposed a risk, analysis methodology. The use of

risk analysis techniques, risk management

techniques and the role of third parties including

vendors, service providers and government agencies

are considered necessary to provide a secure

baseline for small and home-based businesses.

For example, BT Ignite, a large UK-based

vendor of digital certificates and trust services, has

produced “Securing your Website for Business”

(2001), a step-by-step guide for secure online

commerce. The document describes the business

benefits of online trading using digital certificates

interspersed with outline details about how the

featured technologies operate.

The UK DTI Information Security Policy Group

aim to assist businesses to manage information

security effectively and provide a number of entry

point documents, on the DTI “Information Security

website” (n.d.), including “Information Security

Assurance Guidelines for the Commercial Sector”

(n.d.). Based upon ISO/IEC 17799 and IT Security

Evaluation and Certification Scheme (ITSEC)

guidelines, this document considers security issues

in terms of business organisation, product usage and

the supply chain. “Protecting Business Information

Understanding the Risks” (n.d.), outlines

ON INFORMATION SECURITY GUIDELINES FOR SMALL/MEDIUM ENTERPRISES

5

vulnerability assessment, security classification and

information security assurance. “The Business

Manager’s Guide to Information Security” (n.d.),

provides a definition of information security,

outlines its importance, considers the best

approaches, describes roles and responsibilities,

security policies and security solutions. “OECD

Guidelines for the Security of Information Systems

and Networks” (2002), describe a need for a greater

awareness and understanding of security issues and

the need to develop a “culture of security”.

The AEB has produced the “AEB web security

guidelines” (2002). The guidelines provide a

framework for developing and implementing

security measures that affect web sites and e-

business processes. The topics addressed by the

guidelines cover asset classification and risk, risk

assessment and management, security policy,

security responsibility, personnel security, physical

and environmental security, secure web site

management, web site systems development, access

control, encryption and authentication policies, legal

compliance, business continuity management, and

the test and review of security policy.

The National Institute of Standards and

Technology [NIST] Computer Security Expert Team

[CSEAT] has created a US federal agency self-

assessment questionnaire based upon nine

“Automated Information Security Program Review

Areas” (n.d.), derived from the NIST Special

Publication 800-26, “Security Self-Assessment

Guide for Information Technology Systems”

(Swanson, 2001). Each of the nine primary review

areas has further sub-areas defined. Each review

topic area contains critical elements, references and

maturity levels. The review topic areas comprise of

budget and resources, computer security

management and culture, computer security plans,

incident and emergency response, IT security

controls, life cycle management, operational security

controls, physical security and security awareness,

training, and education.

The questions are separated into three major

areas, 1) management controls, 2) operational

controls and 3) technical controls. This division of

control areas compliments three other NIST Special

Publications: NIST Special Publication 800-12, “An

Introduction to Computer Security: The NIST

Handbook” (1995), a handbook, NIST Special

Publication 800-14, “Generally Accepted Principles

and Practices for Securing Information Technology

Systems” (Swanson and Guttman, 1996), details

principles and practices, and NIST Special

Publication 800-18, “Guide for Developing Security

Plans for Information Technology Systems”

(Swanson, 1998), a planning guide.

CSEAT advises using all three documents to

complete the questionnaire: the handbook for

additional detail; principles and practices to provide

a description of each security control; and the

planning guide to form the basis of the question.

To measure progress toward effective

implementation of each security control, five levels

of effectiveness are provided for each answer to

each security control question. The levels are:

• Level 1 – control objectives documented in a

security policy

• Level 2 – security controls documented as

procedures

• Level 3 – procedures have been implemented

• Level 4 – procedures and security controls are

tested and reviewed

• Level 5 – procedures and security controls are

fully integrated into a comprehensive program

The CSEAT method for answering the questions

is based upon an examination of the relevant

documentation and a test of the controls. The

Planning Guide comments that the first use of the

checklist will involve considerable effort. However,

a completed questionnaire can be used as a baseline

for future annual rounds of assessment.

As the examples above illustrate, the various

approaches described frequently overlap. They are

often aimed at different sizes and types of

organization, have differing levels of detail, and may

be partial or proprietary in their scope and coverage.

From the viewpoint of an individual SME faced

with commercial pressures and ICT challenges the

authors believe that much of the information security

advice available is more likely to confuse than to

guide.

4 AN INFORMATION SECURITY

AWARENESS ROADMAP

The CSEAT approach outlined above provides US

federal agencies with a complete, referenced and

auditable self-assessment solution for assessing the

current state of information security maturity across

the breadth of information security issues. In

contrast, the AEB web guidelines described above

provide useful management-level guidance for

securing a web site.

ICEIS 2004 - INFORMATION SYSTEMS ANALYSIS AND SPECIFICATION

6

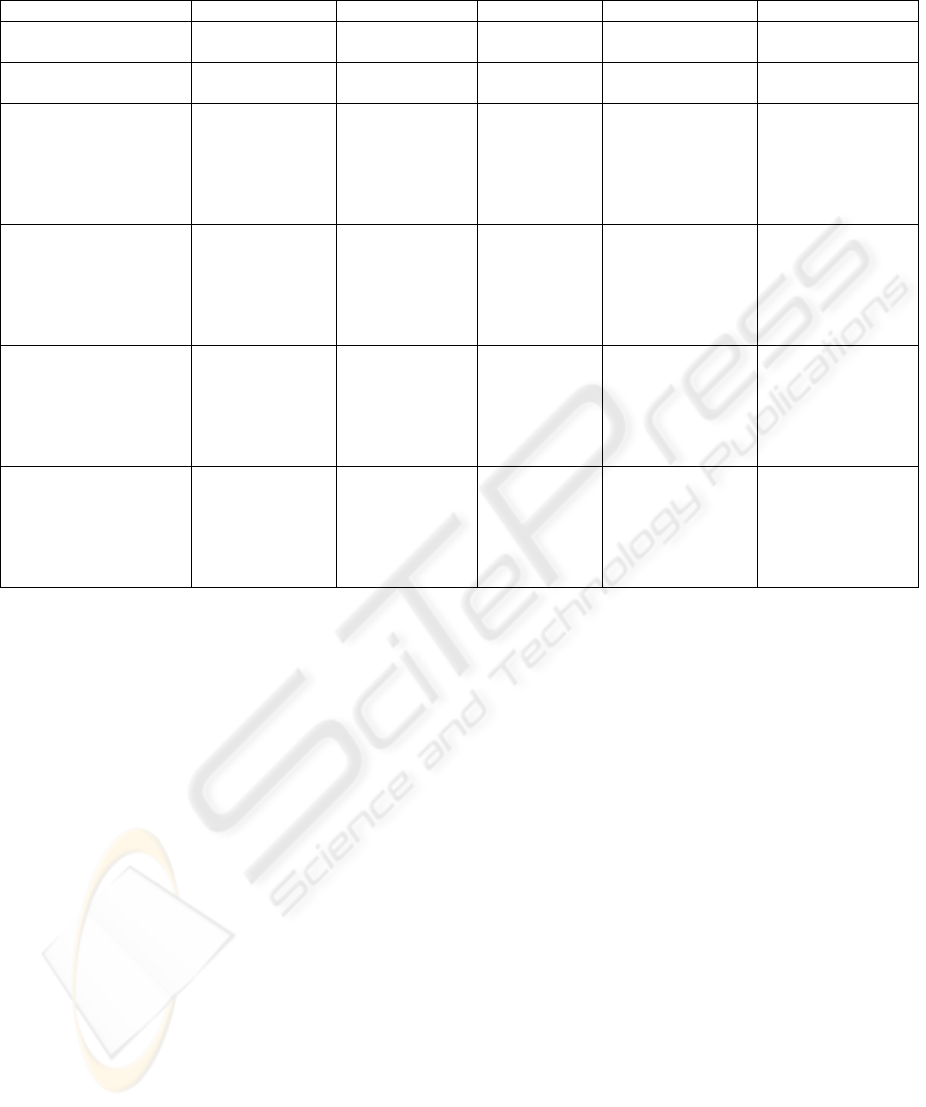

Table 1: Mapping CSEAT to AEB

AEB Topic Level 1 Level 2 Level 3 Level 4 Level 5

Asset Classification

and Control

Listing of Assets

What assets are owned

by the web site, e.g.

content and application

data, web server?

Is there a policy

that requires the

listing of web

site assets?

Are there

procedures for

listing web site

assets?

Have web site

assets been

recorded?

Is there a periodic

review to verify

that web site

assets are

recorded?

Is recording of

web site assets on

a yearly basis

standard business

practice?

What assets are shared

by the web site, e.g.

network infrastructure?

Is there a policy

that requires the

listing of shared

web site assets?

Are there

procedures for

listing shared

web site assets?

Have shared

web site

assets been

recorded?

Is there a periodic

review to verify

that shared web

site assets are

recorded?

Is recording of

shared web site

assets on a yearly

basis standard

business practice?

Are there any

dependent assets, e.g.

power supplies?

Is there a policy

that requires the

listing of

dependent

assets?

Are there

procedures for

listing

dependent

assets?

Have

dependent

assets been

recorded?

Is there a periodic

review to verify

that dependent

assets are

recorded?

Is recording of

dependent assets

on a yearly basis

standard business

practice?

Are there any assets

owned by third parties,

e.g. information,

services?

Is there a policy

that requires the

listing of third

party assets?

Are there

procedures for

listing third

party assets?

Have third

party assets

been

recorded?

Is there a periodic

review to verify

that third party

assets are

recorded?

Is recording of

third party assets

on a yearly basis

standard business

practice?

It is suggested that the number of control areas

and level-of-detail required for answering self-

assessment questions using the CSEAT approach

may deter SMEs from successfully completing a

detailed security assessment. Documents such as

the AEB web guidelines, whilst accessible and

useful within their scope, may fail to cover all the

control areas where an awareness of information

security is required.

The authors believe that a combination of

approaches may prove helpful to an SME. For

example, combining elements of the CSEAT

matrix approach with the Asset Classification and

Control section of the AEB web security

guidelines yields the results shown in table 1

above. Presenting an SME with such a

questionnaire is not intended to be prescriptive, but

it is anticipated that by answering the self-

assessment questions an SME will be able to more

easily determine their current state of information

security awareness.

5 CONCLUSIONS AND

FURTHER WORK

SMEs are frequently unaware of the real extent of

the information security threats they face. They

may lack information security awareness,

necessary skills sets and resources for assessing

their risks. They may also not be aware of

available remedies. Government agencies, service

providers and vendors can all contribute to

increasing levels of awareness and protection

against the risk of information security breeches.

SMEs have a problem in regard to information

security awareness. At one extreme there are

voluminous, high-ceremony guidelines and

detailed best practice advice provided by

information security organisations principally

targeted at Government-related or larger

institutional users. At the other extreme there are

piecemeal, partial and vendor-centric documents

aimed at general or specific issues and

technologies.

The authors consider that only a small

proportion of the available information security

literature will prove relevant to the situation of an

individual SME. The issue of matching generic

ON INFORMATION SECURITY GUIDELINES FOR SMALL/MEDIUM ENTERPRISES

7

best practice and detailed guidance onto pragmatic

information security advice relevant to the needs of

a specific SME requires considerable further study.

The authors have identified a number of areas

for further work, including the identification and

classification of security policy models and

information security guidance considered relevant

to the needs of SMEs. This may lead to the

development of an SME focussed security program

review possibly modelled on the CSEAT

“Automated Information Security Program Review

Areas” (n.d.) seeking to provide self-assessment in

the key review areas.

A further literature review into SME ICT

adoption and the particular problems faced in

regard to information security may enable a

comparison to be made between UK, European

and US-based SMEs.

An investigation into the impact on SMEs of

component-based software-frameworks (for

example, Microsoft .NET) and Application Service

Provider (ASP) solutions in regard to managed

information security may prove informative.

Ultimately, it is hoped to develop a detailed

information security roadmap for a specific

industry set of SMEs.

REFERENCES

2001 International Benchmarking Study. (2001).

Retrieved January 19, 2004, from DTI Web site:

http://resources.ukonlineforbusiness.gov.auk/Type/

Benchmarking_reports/

AEB web security guidelines. (2002). Retrieved April 14,

2003, from Intellect Web site:

http://www.cssa.co.uk/publications/

business_guidance_papers/web_sec_guidelines.pdf

An Introduction to Computer Security: The NIST

Handbook. (1995). NIST. Retrieved May 24, 2003

from NIST Web site: http://csrc.nist.gov/

publications/nistpubs/800-12/ handbook.pdf

Anderson, R. (2001). Security Engineering. UK: John

Wiley & Sons.

Automated Information Security Program Review Areas.

(n.d.). Retrieved May 24, 2003, from NIST Web

site: http://csrc.nist.gov/cseat/Infosec_pgm_rev.html

Bell, D., & LaPadula, L. (1973). Secure Computer

Systems: Mathematical Foundations and Model.

MITRE Corporation.

Biba, K. (1975). Integrity Considerations for Secure

Computer Systems. Mitre Corporation.

Chesher, M., Skok, W. (2000). Roadmap for Successful

Information Technology Transfer for Small

Businesses. Proceedings of the 2000 ACM SIGCPR

conference.

Common Criteria for Information Security Evaluation –

Part 1: Introduction and General Model. (1999).

Retrieved May 18, 2003, from NIST Web site:

http://csrc.nist.gov/cc/Documents/CC 20v2.1/p1-

v21.pdf

Information Security Assurance Guidelines for the

Commercial Sector. (n.d.). Retrieved January 19,

2004, from DTI Web site:

http://www.dti.gov.uk/industry-files/pdf/cag1.pdf

Information Security website. (n.d.). Retrieved May 18,

2003, from DTI Web site: http://www.dti.gov.uk/

industries/information_security

Information Technology – Code of Practice for

information security management. (2000). ISO/IEC

17799.

Miller, A. (n.d.). Small firms at risk from hackers.

Retrieved May 13, 2003, from:

http://www.vnunet.com/News/1105297

OECD Guidelines for the Security of Information

Systems and Networks. (2002). Retrieved January

19, 2004, from DTI Web site: http://www.dti.gov.uk/

industry_files/word/ M00034478 202.doc

Protecting Business Information Understanding the

Risks. (n.d.). Retrieved from DTI Web site:

http://www.dti.gov.uk/industry_files/pdf/

understanding.pdf

Securing your Website for Business. (2001). Retrieved

March 10, 2003, from Ignite BT Web site:

http://www.ignite.com/application-services/

products/verisign/pdf/SecureServerWP06062001.pdf

Systems Security Engineering Capability Maturity

Model. (1999). ISO/IEC 21827, Retrieved May 13,

2003, from: http://www.sse-cmm.org

Systems Security Engineering Capability Maturity

Model: The Appraisal Method. (1999). Retrieved

May 13, 2003, from: http://www.sse-cmm.org

The Business Manager’s Guide to Information Security.

(n.d.). Retrieved from DTI Web site:

http://www.dti.gov.uk/industry_files/pdf/

bus_man_guide.pdf

Siponen, M. (2002). Designing secure information

systems and software: critical evaluation of the

existing approaches and a new paradigm .

Dissertation, University of Oulu.

Siponen, M. (2003). Information Security Management

Standards: Problems and Solutions. 7

th

Pacific Asia

Conference on Information Systems, Adelaide,

South Australia.

Spinellis, D., Gritzalis, D. (1999). Information Security

Best Practise Dissemination: The ISA-EUNET

Approach. WISE 1:First World Conference on

Information Security Education, p111-136.

Spinellis, D., Kokolakis, S. Gritzalis, D. (1999). Security

requirements, risks and recommendations for small

enterprise and home-office environments. Retrieved

May 14, 2003, from:

ICEIS 2004 - INFORMATION SYSTEMS ANALYSIS AND SPECIFICATION

8

http://www.dmst.aueb.gr/dds/pubs/jrnl/1999-IMCS-

Soft-Risk/html/soho.pdf

Swanson, M. (1998). Guide for Developing Security

Plans for Information Technology Systems. NIST.

Retrieved May 13, 2003 from: http://csrc.nist.gov/

publications/nistpubs/800-18/Planguide.pdf

Swanson, M. (2001). Security Self-Assessment Guide for

Information Technology Systems. NIST. Retrieved

March 10, 2003 from NIST Web site:

http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800-

26/sp800-26.pdf

Swanson, M. and Guttman, B. (1996). Generally

Accepted Principles and Practices for Securing

Information Technology Systems. NIST. Retrieved

May 13, 2003 from NIST Web site:

http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800-

14/800-14.pdf

ON INFORMATION SECURITY GUIDELINES FOR SMALL/MEDIUM ENTERPRISES

9