AN INTELLIGENT TUTORING SYSTEM FOR DATABASE

TRANSACTION PROCESSING

Steve Barker

King’s College London

Strand, London, UK

Paul Douglas

Westminster University

115 New Cavendish St, London, UK

Keywords:

Intelligent tutoring systems, databases, e-learning.

Abstract:

We describe an intelligent tutoring system that may be used to assist university-level students to learn key

aspects of database transaction processing. The tutorial aid is based on a well defined theory of learning, and

is implemented using PROLOG and Java. Some results of the evaluation of the learning tool are presented to

demonstrate its effectiveness as a tutorial aid in an e-learning environment.

1 INTRODUCTION

We describe an item of educational software that we

have developed and have used to help University-

level students to learn certain key notions in database

transaction processing. We call this piece of soft-

ware ITSTP (viz. an Intelligent Tutoring System for

(Database) Transaction Processing).

ITSTP is an item of educational software that is in-

tended to “intelligently” assist computer science stu-

dents in developing their understanding of the CRAS

properties (Barker, 1998). The term “intelligently” is

interpreted by us as the capability of responding to

a student’s self-selected input by detecting, diagnos-

ing and explaining his/her errors or confirming that

his/her understanding is correct.

ITSTP is a learning aid that is able to respond to

questions about CRAS property satisfaction in the

same way that an “expert tutor” might and provides

students with a tool for constructing their own learn-

ing experience, an attractive feature that textbooks do

not provide. More specifically, ITSTP encourages

students to learn about the CRAS properties by mak-

ing and testing hypotheses. This approach appears

to us to be the approach that students naturally adopt

to learn about the CRAS properties. The traditional,

text-based method that we have previously used to

teach the CRAS properties does not adequately sup-

port learning by hypothesis formulation and testing.

Although ITSTP has thus far been used to help stu-

dents to learn about CRAS property satisfaction, IT-

STP may be modified to provide support for students

learning any part of the Computer Science curriculum

that involves reasoning about the consequences of the

occurrences of events.

The rest of the paper is organized thus. Section 2

introduces the CRAS properties. In Section 3, the de-

velopment of ITSTP is discussed and a sample of a

user session is given. Section 4 gives details of the

implementation. In Section 5, some results, produced

from our evaluations of ITSTP, are described and dis-

cussed. In Section 6, conclusions are drawn, and sug-

gestions are made for further work.

2 THE CRAS PROPERTIES

Conventionally, the performance of a read (write) op-

eration by transaction t

i

(where i stands for a natu-

ral number that identifies a particular transaction in a

schedule) on a database item x is denoted in the lit-

erature by r

i

(x) (w

i

(x)). That is, when an item x

of data (e.g. a record, a set of records, the value of a

field of a record, . . .) is read from a database on behalf

of a transaction t

i

the performance of that operation

is denoted by r

i

(x). Reading a data item x causes a

copy of x to be transferred from the stable database

and into main memory; x can then be updated. The

writing back to stable storage of a value of x that is

updated by transaction t

i

is denoted by w

i

(x).

In addition to read and write operations, a schedule

may also contain operations to signal the successful

completion of a transaction (its commit point) or its

197

Barker S. and Douglas P. (2004).

AN INTELLIGENT TUTORING SYSTEM FOR DATABASE TRANSACTION PROCESSING.

In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, pages 197-203

DOI: 10.5220/0002606701970203

Copyright

c

SciTePress

failure (and, thus, abortion). The commit (abort) of a

transaction t

i

is denoted by c

i

(a

i

).

It follows from this discussion that a schedule

is some sequence of read, write, abort and com-

mit operations. For example, the schedule, s =

hr

1

(x), w

2

(x), w

1

(x), c

1

, a

2

i denotes that after trans-

action t

1

’s read operation on data item x is performed,

transaction t

2

writes x before t

1

writes x, and then

commits. Finally, t

2

aborts.

The four CRAS properties (Kumar, 1996) are:

Conflict Serialisability (CS), Recoverability (RC),

Avoids Cascading Aborts (ACA), and Strictness (ST).

As previously mentioned, the satisfaction of these

properties is tested for by a DBMS to enable it to de-

cide whether a schedule is guaranteed to correctly up-

date a database, and whether efficient recovery tech-

niques may be employed to deal with failures.

Conflict serialisability and recoverability are cor-

rectness criteria. For a schedule to be conflict seri-

alisable, it is essential that no two transactions con-

tain mutually conflicting operations (two operations,

o

1

and o

2

(say), are said to conflict if they refer to

a common data item and at least one of the opera-

tions is a write). If a schedule satisfies the conflict

serialisability criterion then it is certain to avoid the

lost update problem (Kumar, 1996). To satisfy the re-

coverability property, it is essential that the order in

which transactions successfully terminate in a sched-

ule is consistent with the order in which transactions

read the updated values of data items that are writ-

ten to the database. That is, if transaction t

i

writes

a data item x in a schedule s and a transaction t

j

(t

i

6= t

j

) subsequently reads this updated value in s (a

read from by t

j

from t

i

) then t

i

must commit before t

j

in s. Satisfying recoverability ensures that a commit-

ted transaction is not subsequently aborted and, thus,

that a commit point correctly signals the termination

of a successful transaction.

The ACA and ST conditions are practical criteria

that, if satisfied, reduce the amount of work that needs

to be performed in order to recover from the effects of

failed transactions and enable a particularly efficient

method to be employed to manage aborted transac-

tions. As the name suggests, satisfying the avoiding

cascading aborts condition ensures that if a transac-

tion aborts then it does not cause a chain (or cascade)

of aborting transactions to arise. That is, the failure of

one transaction, t

1

(say), does not cause another trans-

action, t

2

(say), to fail which causes another trans-

action t

3

(say) to fail and so on. For schedules that

satisfy the property of strictness, a particularly effi-

cient approach may be used to recover from the ef-

fects of failed transactions. If a schedule is strict then

the value of any of the data items that are written by an

aborted transaction in a schedule can be simply reset

to the value they had prior to the transaction running

(the before image).

We define the CRAS properties formally below. In

these definitions, t

i

and t

j

denote arbitrary transac-

tions, T (σ) is an arbitrary schedule σ defined on a set

of transactions T , r

i

, w

i

, a

i

and c

i

are respectively

read, write, abort and commit operations by transac-

tion t

i

, → is “implication”, ∧ is ‘and’, ∨ is ‘or’, ¬ is

negation, and < denotes an “earlier than” relationship

between operations. The meanings of the read from

and conflict predicates are as explained above.

Definition 1 A schedule σ on a set of transactions T

is conflict serialisable iff the following holds:

∀t

i

, t

j

∈ T (σ) conf lict(t

i

, t

j

) → ¬conf lict(t

j

, t

i

)

where conflict is defined thus:

∀t

i

, t

j

∈ T (σ) r

i

(x) < w

j

(x) → conf lict(t

i

, t

j

)

∀t

i

, t

j

∈ T (σ) w

j

(x) < r

i

(x) → conf lict(t

j

, t

i

)

∀t

i

, t

j

∈ T (σ) w

i

(x) < w

j

(x) → conf lict(t

i

, t

j

)

Definition 2 A schedule σ on a set of transactions T

is recoverable iff the following holds:

∀t

i

, t

j

∈ T (σ) read

from(t

i

, t

j

) →

c

j

∈ σ ∧ c

j

< c

i

Definition 3 A schedule σ on a set of transactions T

avoids cascading aborts iff the following holds:

∀t

i

, t

j

∈ T (σ) read

from(t

i

, t

j

) →

c

j

< r

i

(x) ∨ a

j

< r

i

(x)

Definition 4 A schedule σ on a set of transactions T

is strict iff the following holds:

∀t

i

, t

j

∈ T (σ) w

j

(x) < r

i

(x) ∨ w

j

(x) < w

i

(x) →

a

j

< r

i

(x) ∨ c

j

< r

i

(x) ∨ a

j

< w

i

(x) ∨ c

j

< w

i

(x)

Definition 5 The auxiliary predicate read from is

defined thus:

∀t

i

, t

j

∈ T (σ) ∃x[read f rom(t

i

, t

j

)

← w

j

(x) < r

i

(x) ∧ ¬(a

j

< r

i

(x))

∧ [∀t

k

∈ T (σ) w

j

(x) < w

k

(x) < r

i

(x)

→ a

k

< r

i

(x)]].

3 ITSTP: AN OVERVIEW

ITSTP is a piece of software that enables students to

test any syntactically correct schedule they choose as

input to the system. Students also have complete free-

dom to choose to investigate the satisfaction of any of

the CRAS properties by these schedules.

The software that implements ITSTP is written in

PROLOG (Bratko, 2000). PROLOG has been widely

used for implementing items of educational software

ICEIS 2004 - ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEMS

198

(see, for example, (Nichol et al., 1988)) and is appro-

priate for developing applications, like ITSTP, that re-

quire that a degree of “intelligence” be captured. The

fact that the rules that define the CRAS properties can

be directly translated into PROLOG was another rea-

son for us choosing PROLOG to implement ITSTP.

3.1 Our Development Methodology

Our approach to developing ITSTP initially involved

us adopting a phenomenographic method (Marton

and Ramsden, 1988) for information gathering on stu-

dents’ understanding of concepts in transaction pro-

cessing. By conducting ‘dialogue’ sessions with stu-

dents we identified the strategies students used to un-

derstand the CRAS properties. From our review of

the notes taken at the dialogue sessions, we were able

to develop a prototype system for supporting students

in learning about CRAS property satisfaction.

As our ITSTP tool evolved, we made increasing use

of Gagne’s event-based model of instruction (Gagne,

1970) to decide what material a user of ITSTP should

be offered and the order in which information ought

to be presented to a learner. Following (Gagne, 1970),

when students use ITSTP they are reminded what the

learning task to be performed is, and what it is they are

supposed to be able to do once the learning task has

been completed. Prominence is given to the distinc-

tive features that need to be learned, different levels of

learning guidance are supported for different types of

learners, informative feedback is given, and learning

takes place in a student-centred, interactive way, but

with support available to students as and when they

need it.

3.2 A Learning Session

After loading the home page for the system (which

gives a brief overview of how to use the system), the

user engages with ITSTP, by submitting a schedule to

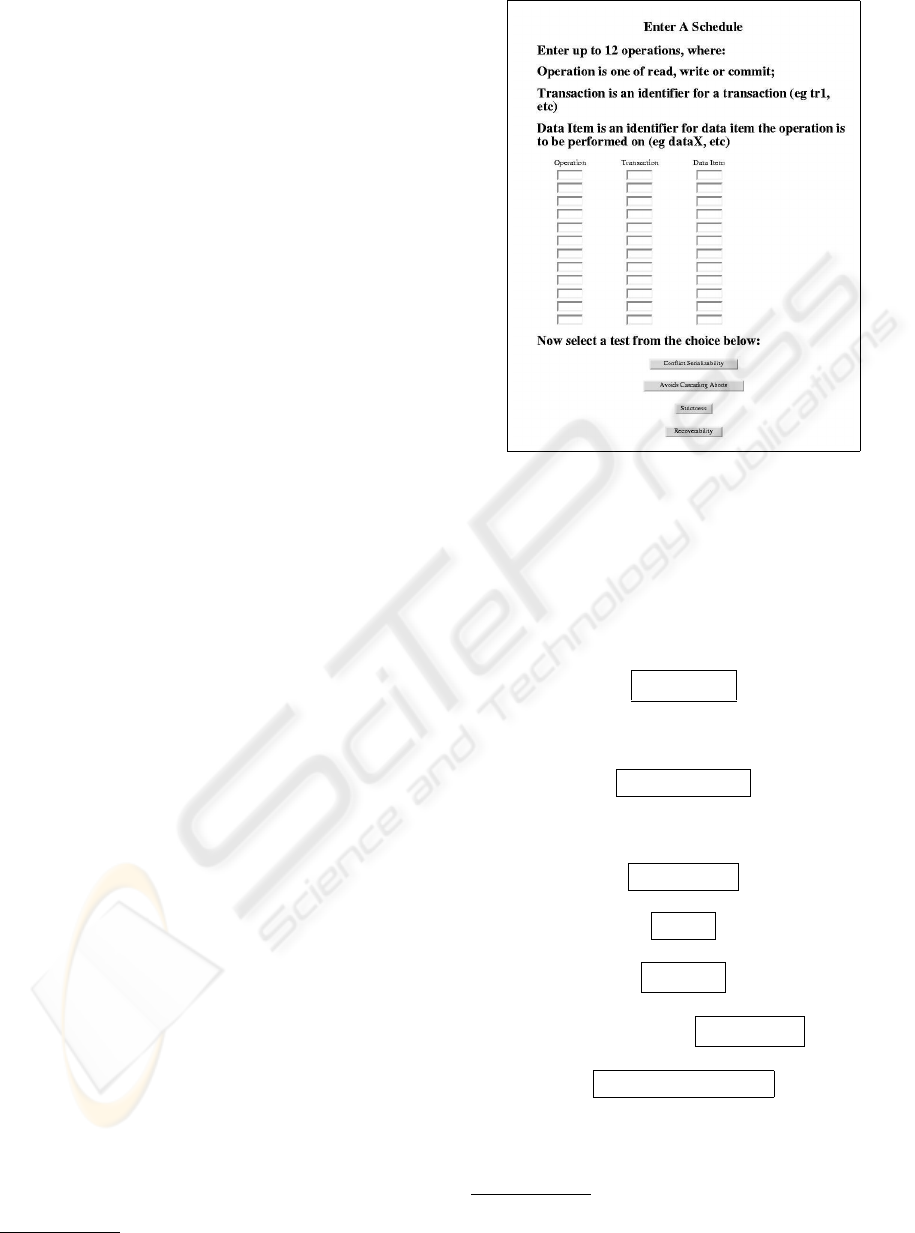

the system, via the page shown in Figure 1.

Each element of a schedule is represented by 3

data entry boxes, which correspond to 3 of the ele-

ments in an underlying 4-ary tuple, (o,t

j

,i,t

s

). Here,

o ∈ {read, write, commit, abort} denotes an opera-

tion, t

j

denotes a transaction performing o, i denotes

the data item acted upon by t

j

, and t

s

is a timestamp,

the time at which o is performed. Timestamps are rep-

resented using a monotonically increasing sequence

of natural numbers. For simplicity, a value for t

s

is

added automatically by the system (hence 3 data entry

boxes are sufficient to represent the 4-tuple (o,t

j

,i,t

s

).

The t

s

values are based on the sequence in which the

operations are entered by the user.

1

In the case where

o is a commit or an abort, the data item is null as these

1

This removes the possibility of the user reordering the

Figure 1: Schedule Entry Page

operations are not performed on a data item. Having

entered a schedule σ, a user can select a CRAS prop-

erty to evaluate with respect to σ.

The property to test is chosen by a simple choice of

buttons on the Schedule Entry page. All further nav-

igation is achieved following this convention, based

on the following menu plan:

Home Page

↓

→1

↓

Enter Schedule

↓

→2

↓

Choose Test

↓

Result

↓

Explain?

. &

↓ Explanation

& .

Choose Another Test

. &

no yes

↓ ↓

1 2

operations by simply changing the timestamps. The test

process revealed that users generally preferred the simplic-

ity of the approach that we have adopted.

AN INTELLIGENT TUTORING SYSTEM FOR DATABASE TRANSACTION PROCESSING

199

which we finalized after the testing process in the

light of student feedback.

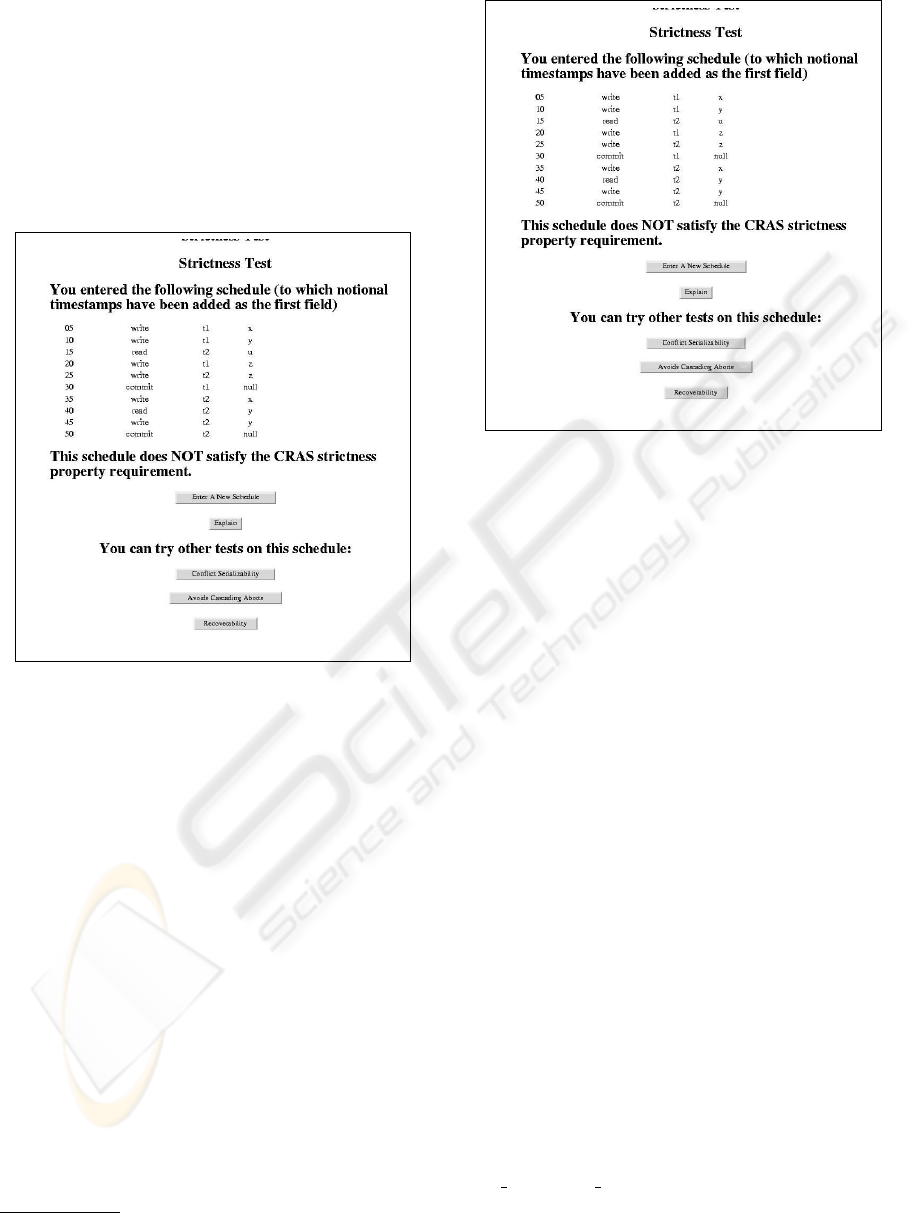

Once a test has been chosen, the system responds

with a page showing the schedule entered by the user

(now with the system-allocated timestamps), and an

indication of whether the schedule is correct with re-

spect to the chosen CRAS property. An example of

the type of page that is generated as output is shown

in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Initial Results Page

Having tested a schedule property, a user can ask

for an explanation of the results obtained by select-

ing the Explain? option button; if the explanation is

insufficient for the user, an option is provided for a

further level of explanation, together with a summary

of the chosen property.

2

A sample explanation page

is shown in Figure 3.

4 THE IMPLEMENTATION

The main program is written in PROLOG. The input

to this program consists of (i) a set of 4-ary tuples (see

above) that represents a schedule σ, and (ii) a spe-

cific goal clause (corresponding to one of the CRAS

properties). The program evaluates the goal clause

with respect to σ, and returns either “true” or “false”.

Further goal clauses allow testing of the other CRAS

properties, or can be used to produce an explanation

of why a “false” result has been returned.

2

This opens in an additional browser window, and has

been omitted from the menu outline above.

Figure 3: Explanation Page

We used XSB (Sagonas et al., 1999) to implement

this program. XSB offers excellent performance that

has been demonstrated to be far superior to that of tra-

ditional Prolog-based systems (Sagonas et al., 1994).

It is also widely used for Prolog system development,

and offers a wide range of interface packages and li-

braries, making it easy to combine with other applica-

tions.

The main program is called via a Java program that

provides the main interface. Java is a suitable lan-

guage for this type of application because of its com-

prehensive internet application support. In addition,

it is easy to access applications written in a variety

of other languages (through the Java Native Interface

(JNI) mechanism).

Calls to XSB from the Java interface program are

handled by the YAJXB (Decker, ) package. YAJXB

makes use of Java’s JNI mechanism to invoke meth-

ods in the C interface library package supplied by

XSB. It also handles all of the data type conversions

that are needed when passing data between C and

Prolog-based applications. YAJXB effectively pro-

vides all the functionality of the C package within a

Java environment. The C library allows the full func-

tionality of XSB to be used. A variety of methods

for passing Prolog-style goal clauses to XSB exists.

However, we generally found that the string method

worked well. This method involves constructing a

string S in a Java String type variable, and using the

xsb command string function (or similar) to pass

S to XSB. This approach allows any string that could

be entered as a command when using XSB interac-

tively to be passed to XSB by the Java interface pro-

ICEIS 2004 - ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEMS

200

gram. YAJXB creates an interface object; the precise

method of doing this is a call like

i=core.xsb command string

(command.toString());

where the assignment, as one would expect, han-

dles the returned error code. In the case of the expla-

nation goals, variations on this method allow for the

return of data too, though this is not necessary where

conformity (to a CRAS property) is merely confirmed

or denied.

All of our development was done on a Sun

Sparc/Solaris system. We used Apache’s Tom-

cat (APACHE, ) web server, partly because it was

convenient to do so (it is installed on the University

system we used for testing the software), and partly

because of its simple, threads-based session manage-

ment. Java and XSB are well supported on the Solaris

platform and YAJXB, though primarily configured for

Linux, compiles easily on Solaris.

5 EVALUATING ITSTP

We have adopted a two-phase approach to evaluate IT-

STP. That is, we used a formative evaluation of ITSTP

during the development of the learning tool. There-

after, we conducted a summative evaluation of a pro-

totype version of ITSTP.

5.1 The Formative Evaluation

For the formative evaluation, comments on the soft-

ware were sought from: three members of the teach-

ing staff at the University of Westminster (the “expert

reviewers” (Tessmer, 1993)); a volunteer student from

the university’s MSc course in Database Systems (the

one-to-one study); and a group of six volunteer stu-

dents from the same course (the small-group testing).

The volunteer students were randomly allocated to

either the one-to-one or small-group testing (but not

both). These students were learning about the CRAS

properties at the time at which the formative evalua-

tion of ITSTP was being conducted.

Initial demonstrations to the three expert reviewers

provided some suggestions on how ITSTP could be

improved. In particular, a number of recommenda-

tions were made on improving the user interface. The

suggested improvements were made to ITSTP prior to

us conducting the one-to-one evaluation.

The one-to-one evaluation took place over a period

of two weeks and involved approximately 3 hours of

contact time with the student volunteer. At the first of

the one-to-one sessions, the student was introduced to

ITSTP using a 10 minute presentation. He was pro-

vided with a quick reference guide to remind him of

the basic functions supported in the version of ITSTP

he was to use.

In the one-to-one testing, our data were gathered

using observation and informal “interviews”. This in-

volved one of the authors sitting alongside the subject

and encouraging him to articulate his feelings about

the learning package as he was using it. The student

reported that ITSTP was useful in terms of helping

to develop his understanding of CRAS property sat-

isfaction. He emphasized that ITSTP was motivating

to use, and he repeatedly suggested that the scope IT-

STP provided, to enable him to investigate schedules

of his own choosing, was important in developing un-

derstanding. The student also suggested some useful

modifications to ITSTP. We chose to make several of

the suggested changes before starting our small-group

testing.

The small–group testing was performed over a four

week period (approximately 8 hours of contact time

spread over six sessions) with a set of six student vol-

unteers (three males and three females). The methods

employed to gather data were the same as those used

for the one-to-one sessions.

Again, the power that ITSTP provides to enable

students to investigate any schedule and CRAS prop-

erty was reported to be an attraction of the learning

tool, and important in helping students to develop

their understanding of schedule properties. The stu-

dents also commented positively on the internet avail-

ability of the software: although our small-group test-

ing was limited to that described above, all of the stu-

dents involved in the formative evaluation of ITSTP

reported that they had used the learning tool, via the

web, on several additional occasions outside of the

test sessions.

The feedback collected from students engaging in

the small–group testing was used by us to develop IT-

STP further and prior to its summative evaluation.

5.2 Summative Evaluation of ITSTP

The field test of ITSTP was conducted with the co-

hort of 29 students at the University of Westminster

who were taking the Database Administration (DBA)

module as part of their part-time BSc Computer Sci-

ence degree programme in the Second Semester of the

2002/2003 academic year.

Students were introduced to the version of the IT-

STP software to be summatively evaluated during a 2

hour tutorial session; the introduction was presented

identically to that used in the one-to-one and small-

group testing. Following the introductory session, IT-

STP was used for the next three weeks during the part-

time students’ tutorial time.

In overview, there were two parts to the summative

evaluation of ITSTP. Firstly, a t-test was performed on

the results of a phase test that included questions on

AN INTELLIGENT TUTORING SYSTEM FOR DATABASE TRANSACTION PROCESSING

201

the CRAS properties. The t-test was intended to com-

pare the performance of the part-time students (the ex-

perimental group) with that of the 47 full-time DBA

students (the control group) who had used the stan-

dard module text (Bernstein et al., 1987), henceforth

denoted by B, but not ITSTP. The full-time students

had taken the same test in the semester before the ex-

perimental group. Secondly, a 5-point Likert scale

was used to produce data on the perceptions the part-

time students had of ITSTP and B, as methods for fa-

cilitating understanding of the CRAS properties, and

their attractiveness as learning instruments. A t-test

was again used to analyse the data produced and was

based on a comparison of the matched pairs of scores

produced by each respondent for ITSTP and B.

Mean test scores for the part-time and full-time stu-

dents for the phase test were calculated for both the

CRAS and non-CRAS related questions to compare

the performance of the two sets of students. Because

we felt that ITSTP might have had an effect in encour-

aging learning gains, we chose to test the alternative

(directional) hypothesis that: the part-time students

performed better on the test of CRAS property under-

standing than the full-time students. The correspond-

ing null hypothesis was that there was no difference

in the phase test scores produced by the two sets of

students.

The analysis of our data showed that the mean test

scores (out of 12) for the full-time and part-time stu-

dents on the questions on CRAS properties were 6.52

and 8.38 respectively (the corresponding standard de-

viations were 9.65 and 6.97, respectively). The com-

puted t-statistic was 0.81 for 27 degrees of freedom.

Hence, the directional hypothesis had to be rejected

in favour of the null hypothesis.

A comparison of the mean scores (out of 28)

achieved by the students on that part of the phase

test that did not directly relate to the CRAS properties

revealed that the average mark for full-time students

was 16.96 whereas the average mark for part-time stu-

dents was 17.58. As such, whereas the average score

for the full-time students on the phase test questions

relating to the CRAS properties was 29% lower than

the part-time students, the average mark for the full-

timers on questions not related to the CRAS proper-

ties was only 4% lower. Although these figures do not

prove anything, they offer some suggestive evidence

that ITSTP might have helped students to understand-

ing the CRAS properties.

The combination of the statistically non-significant

analysis of the phase test scores and the fact that a

number of potentially confounding variables applied

in our study meant that we were not able to draw any

firm conclusions on whether ITSTP had been of value

in terms of helping students understand the CRAS

properties.

The Likert scale included a total of 24 statements

(with an equal number of positive and negative state-

ments). These items were divided into three cate-

gories. Eight of the statements were intended to mea-

sure the extent to which ITSTP and B were perceived

as being of value in facilitating student understanding

of the CRAS properties, a further eight items were

intended to help to decide the extent to which ITSTP

and B were motivating to use, and the remaining eight

statements were used to collect the students’ opinions

on the value of comparable features of ITSTP and B

(i.e., their explanations, exercises and examples). Stu-

dents were asked to indicate their strength of agree-

ment/disagreement with each statement in the Likert

scale. The five options were: strongly agree, agree,

unsure, disagree and strongly disagree.

26 responses to the Likert scale were returned. To

produce the measures of student attitudes, a three-

stage approach was adopted. The initial step involved

“signing” the 24 items included in the Likert scale as

being a positive or negative statement about ITSTP or

B. Next, the returns were analysed using the follow-

ing system: for each positive statement a response of

“strongly agree” was given a score of 5, an “agree”

response was given a score of 4, a score of 3 corre-

sponded to an “undecided” response, “disagree” was

scored as a 2, and “strongly disagree” was scored

as a 1. Conversely, for each negative statement, a

“strongly agree” response was given a score of -5,

“agree”was scored as -4, “undecided” was recorded

as a -3, “disagree” was given a score of -2, and -1 cor-

responded to a “strongly agree” response. By sum-

ming the scores for each return, a figure correspond-

ing to the respondent’s attitude towards ITSTP and B

was computed. In the final step, the B score for each

respondent was subtracted from the score for ITSTP.

This calculation gave a measure of a respondent’s atti-

tude to ITSTP that is relative to their attitude towards

B.

3

To analyse the information produced from the Lik-

ert scale, t-statistics were computed to compare the

mean scores for the perceptions students had of IT-

STP and B, overall and for each of the three categories

of items included in the Likert scale.

In the overall measure of the two methods, the av-

erage difference in the ratings of ITSTP and B was

16.79 in favour of ITSTP, and no student reported that

B was “better” than ITSTP. The t-statistic for the com-

parison of average differences was 2.25. This is sta-

tistically significant at the 2% level. Not surprisingly,

given the overall results, ITSTP was also perceived to

be “better” than B in all three of the sub-categories of

Likert scale items.

In terms of facilitating understanding of the CRAS

3

A positive score indicates a more favourable attitude

towards ITSTP than B; a negative score represents a more

favourable attitude towards B than ITSTP.

ICEIS 2004 - ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEMS

202

properties, the average difference in scores between

ITSTP and B was 2.07, in favour of ITSTP, and all

but four of the students reported that ITST had been

more valuable than B on this measure. In the t-test

comparison of the average difference in the ratings of

ITSTP and B, the t-statistic was 2.18. This value is

significant at the 5% level.

The average difference in the rating of ITSTP and B

on motivational appeal was 10.85, and all but one stu-

dent reported that ITSTP had been more motivating

to use than B. The t-value, of 2.51, for the compari-

son of average differences in ratings between ITSTP

and B on motivational appeal is significant at the 2%

level.

The average difference in scores on the value of

the exercises, explanations and examples was 4.63 in

favour of ITSTP. The t-statistic for the average differ-

ence was 3.21, which is significant at the 1% level.

6 CONCLUSIONS AND FURTHER

WORK

We have described an intelligent tutorial aid, ITSTP,

that may be used by undergraduate computer science

students to learn about transaction schedule proper-

ties. The tutorial aid enables students to create their

own learning environments. ITSTP can respond to

student input in the way that an “expert tutor” might

and provides extensive explanation facilities and on-

line exercises. The results of our analysis of ITSTP

suggest that the tool is perceived by its users to be of

value in facilitating understanding of the CRAS prop-

erties, and ITSTP is reported by users to be motivat-

ing to use. A longitudinal study of the effectiveness of

ITSTP as a learning tool is a matter for further work.

Although currently focussed on the CRAS proper-

ties, extended forms of ITSTP are possible to support

students’ learning other topics in the University-level

Computer Science curriculum (e.g., database recov-

ery techniques and state machines (Borger and Stark,

2003)). Being web-based, ITSTP is suitable for use

by Computer Science students taking courses in dis-

tance learning mode; investigating the use of ITSTP

in a distance learning environment is another matter

for future work.

REFERENCES

APACHE. The Apache Software Foundation.

http://www.apache.org.

Barker, S. (1998). Proving properties of schedules. In Proc.

IEEE Workshop on Knowledge and Data Engineer-

ing, pages 174–180.

Bernstein, P., Goodman, N., and Hadzilacos, V. (1987).

Concurrency Control and Recovery in Database Sys-

tems. Addison Wesley.

Borger, E. and Stark, R. (2003). Abstract State Machines.

Springer.

Bratko, I. (2000). PROLOG Programming for Artificial In-

telligence. Addison-Wesley.

Decker, S. Yet Another Java XSB Bridge. http://www-

db.stanford.edu/%7Estefan/rdf/yajxb/.

Gagne, R. M. (1970). The Conditions of Learning. Holt,

Reinhart and Winston.

Kumar, V. (1996). Performance of Concurrency Control

Mechanisms in Centralised Database Systems. Pren-

tice Hall.

Marton, F. and Ramsden, P. (1988). What does it take to

improve learning? Kogan Page.

Nichol, J., Briggs, J., and Dean, J. (1988). Prolog, Children

and Students. Kogan-Page.

Sagonas, K., Swift, T., and Warren, D. (1994). Xsb as an ef-

ficient deductive database engine. In ACM SIGMOD

Proceedings, page 512.

Sagonas, K., Swift, T., Warren, D., Freire, J., and Rao, P.

(1999). The XSB System Version 2.0, Programmer’s

Manual.

Tessmer, M. (1993). Planning and Conducting Formative

Evaluations. Kogan-Page.

AN INTELLIGENT TUTORING SYSTEM FOR DATABASE TRANSACTION PROCESSING

203