COMMUNICATION AND ENTERPRISE ARCHITECTURE IN

EXTENDED ENTERPRISE INTEGRATION

i

Frank Goethals

1

, Jacques Vandenbulcke

1

, Wilfried Lemahieu, Monique Snoeck, Manu De Backer,

Raf Haesen

F.E.T.E.W. – K.U.Leuven – Naamsestraat 69, B-3000 Leuven, Belgium

1

SAP-leerstoel Extended Enterprise Infrastructures

Keywords: Communication gap, Enterprise Architecture, Business-to-Business integration, Extended Enterprise

Abstract: Business-to-Business integration (B2Bi) is considered

to be not merely an IT-issue, but also a business

problem. This paper draws attention to the two communication gaps companies within an Extended

Enterprise are confronted with when integrating their systems. To overcome these communication problems

we propose the use of Enterprise Architecture descriptions. Therefore we give a bird’s-eye view of what

Enterprise Architecture descriptions could look like in the context of the Extended Enterprise, as well as the

compelling advantages that can be gained from using such descriptions in integration exercises. This paper

is no how-to guide for Extended Enterprise Architecture but is meant to show the importance of Enterprise

Architecture descriptions in this realm, something that is heartrendingly

neglected.

1 INTRODUCTION

Nowadays companies are offering Web services (i.e.

information system services) to other companies,

and are using Web services offered by other

companies. The business and IT landscapes have

turned more complex than ever, and the creation and

automation of processes that involve services of

different companies is an evolutionary challenge. In

the past, many IT projects have failed, and many

will fail in the future if no better way is found to

handle IT investments. Above this, partnerships can

be harmed if the envisioned IT integration projects

between partners fail. In this article, we propose the

use of architecture descriptions as a means to

support the integration of systems at a Business-to-

Business (B2B) level, and more specifically at the

level of the Extended Enterprise (see below). In

what follows we first structure the B2B domain, and

set forth basic observations concerning B2B

integration (B2Bi) practices we should keep in mind

when searching for an elegant solution to the

integration problem. Next, in Section 3, we define

the communication problems that arise when

developing Web services for the Extended

Enterprise; and finally, in Section 4, we introduce

the idea of Extended Enterprise Architecture

Descriptions as a means to solve the communication

problems.

2 STRUCTURING THE B2B

DOMAIN

From the theory on the network form of

organizations (see e.g. Podolny and Page (1998)), it

is clear that companies are involved in an

organizational integration at three levels, namely

- at th

e level of the individual enterprise the

different departments have to be integrated,

- at th

e level of the Extended Enterprise the

companies that make up the Extended Enterprise

have to be integrated. By the term Extended

Enterprise (EE), we mean a collection of legal

entities (N ≥ 2) with a collaborative mindset that

pursue repeated, enduring exchange relations

with one another.

- at th

e level of the market a very loose coupling is

present with companies in the environment

(other than those within the Extended

Enterprise). With these companies no long term

relationship is envisioned.

It is remarkable that an Extended Enterprise truly

fo

rms a new enterprise that has a starting point and

an endpoint (in time). Consequently, this new

(extended) enterprise can (and should) be architected

by a group of people (including CEO and CIO) of

the partnering companies! This is in contrast to

doing business in the marketplace, where

332

Goethals F., Vandenbulcke J., Lemahieu W., Snoeck M., De Backer M. and Haesen R. (2004).

COMMUNICATION AND ENTERPRISE ARCHITECTURE IN EXTENDED ENTERPRISE INTEGRATION.

In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, pages 332-337

DOI: 10.5220/0002620803320337

Copyright

c

SciTePress

transactions happen at isolated moments in time and

no new enterprise is formed.

There should be a fit between an organization's

structure, its technology, and the requirements of its

environment. As companies within an EE face two

shells of environment (organizations within the EE

vs. organizations outside the EE), they need appro-

priate IT approaches to deal with each type of envi-

ronment. Consequently, we may say that companies

are confronted with three types of information

systems integration. Firstly, companies have to deal

with the integration of their internal systems (Enter-

prise Application Integration, EAI). Stovepiped

systems – often made to fit the requirements of one

department – need to be integrated. Secondly, there

is an integration with systems of other companies

within the EE. We refer to this as EEi (EE

integration). Thirdly, companies may want to

integrate their systems with those belonging to other

companies than close partners. We call this Market

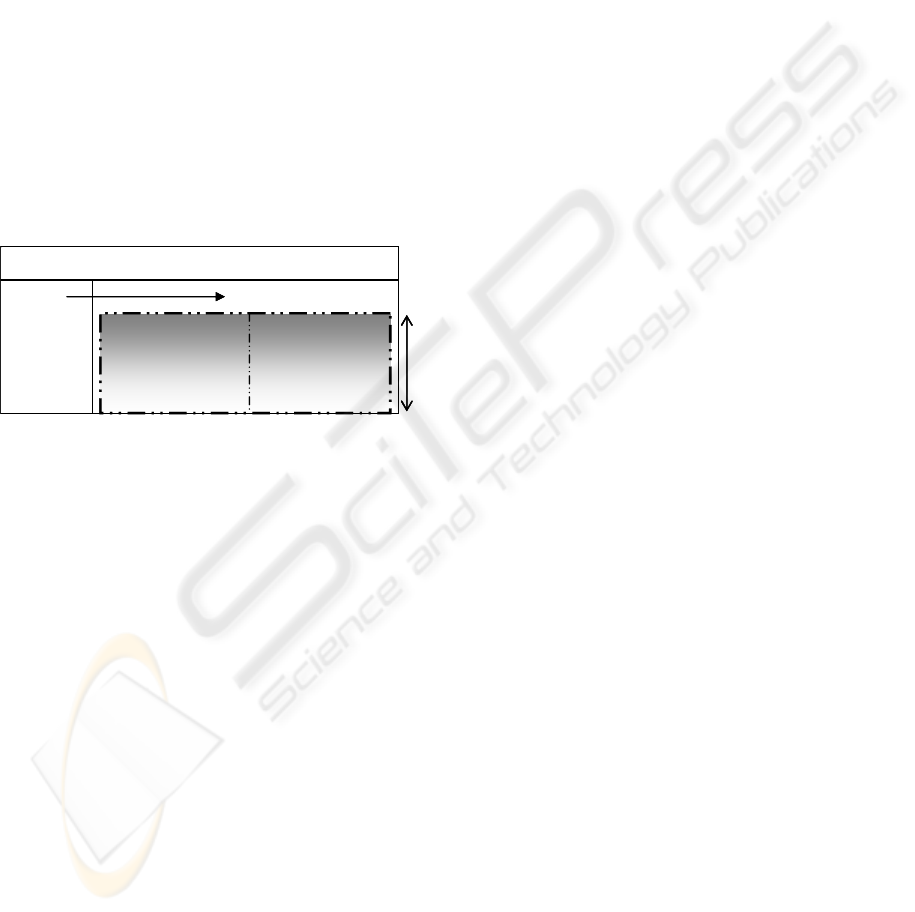

B2Bi. The three types are represented in Figure 1.

Systems Integration

EAI

B2Bi

EEi

Market B2Bi

S

D

Systems Integration

EAI

B2Bi

EEi

Market B2Bi

S

D

Figure 1: Three types of systems integration

These three types of integration each have their

own specific issues. An important difference

between EEi and Market B2Bi for example is that

the human link between the companies is much less

substantial for the latter. Also, Market B2Bi may

include using services of parties that were unknown

upfront, implying there should be a way to find the

parties and the desired Web services. Unfortunately,

the difference between these two forms of B2Bi is

usually neglected in literature on IT!

For each of the three types of integration, we

witness/foresee an evolution from static integration

to more flexible, dynamic forms of integration

(depicted by the ‘S’ and ‘D’ in Figure 1). At the

level of collaborating companies, the (relatively

new) Web services paradigm is more flexible than

(the older) EDI (Electronic Data Interchange) tech-

nology. Also, in the future B2Bi could be enhanced

by software agents that are capable of searching and

binding Web services autonomously. Please note

that, as is indicated by the arrow in Figure 1, EAI

should precede B2Bi (see e.g. Linthicum (2000)).

One point that should be kept in mind when

integrating businesses is that doing business is still

about people’s requirements, not just about IT. Note

that in the commodity goods market, companies are

not just offering goods without investigating which

goods the consumers exactly want. Companies

should become consumer-oriented in the Web

services domain too, i.e., companies should research

which Web services interest business people from

other companies rather than simply offering the

services their own IT department deems useful.

Many cases have illustrated the importance of

documenting IT systems. If the knowledge

concerning the system is only in the heads of the

personnel a company is exposed to threats, as

personnel may retire, forget, etc. Many problems in

systems integration stem from ignorance.

3 REVEALING THE

COMMUNICATION PROBLEMS

Many Web service integration challenges stem from

communication problems (Goethals et al., 2003). In

what follows we focus on two issues. First we

propose challenges related to the concept of

consumer-oriented Web services. Next, we discuss

the idea of Web services choreographies to show

how important communication can be.

3.1 The Quest for Consumer-

Oriented Web Services Reveals

Two Communication Gaps

Nowadays, companies are offering Web services to

partners and other parties. When developing Web

services, it is important to know the functional and

non-functional requirements of the future service

consumer. However, at current in actual practice the

attention seems to go much more to playing with

Web services technology than to using the new

technology in a way interesting to businesses

(Frankel and Parodi, 2002).

In realizing consumer-oriented Web services

many problems may arise. For many years, the

problem of business-ICT alignment has annoyed

companies. Nowadays, an extra gap arises besides

the one between business and ICT; namely the one

between the different companies in an EE

ii

. Pollock

(2002) states that most problems contributing to the

high failure rates of integration projects are not

technical in nature. He points out the importance of

semantics in B2Bi. While misunderstandings (and

semantic obscurities) within a company may be

large, the problems only increase when looking at

relations among different companies. Please note

that this gap is not only present at business level, but

also at IT-level. A Database (DB) in one company

COMMUNICATION AND ENTERPRISE ARCHITECTURE IN EXTENDED ENTERPRISE INTEGRATION

333

may for example use the term ‘custno’ to denote the

same concept as ‘customerID’ in an other’s DB.

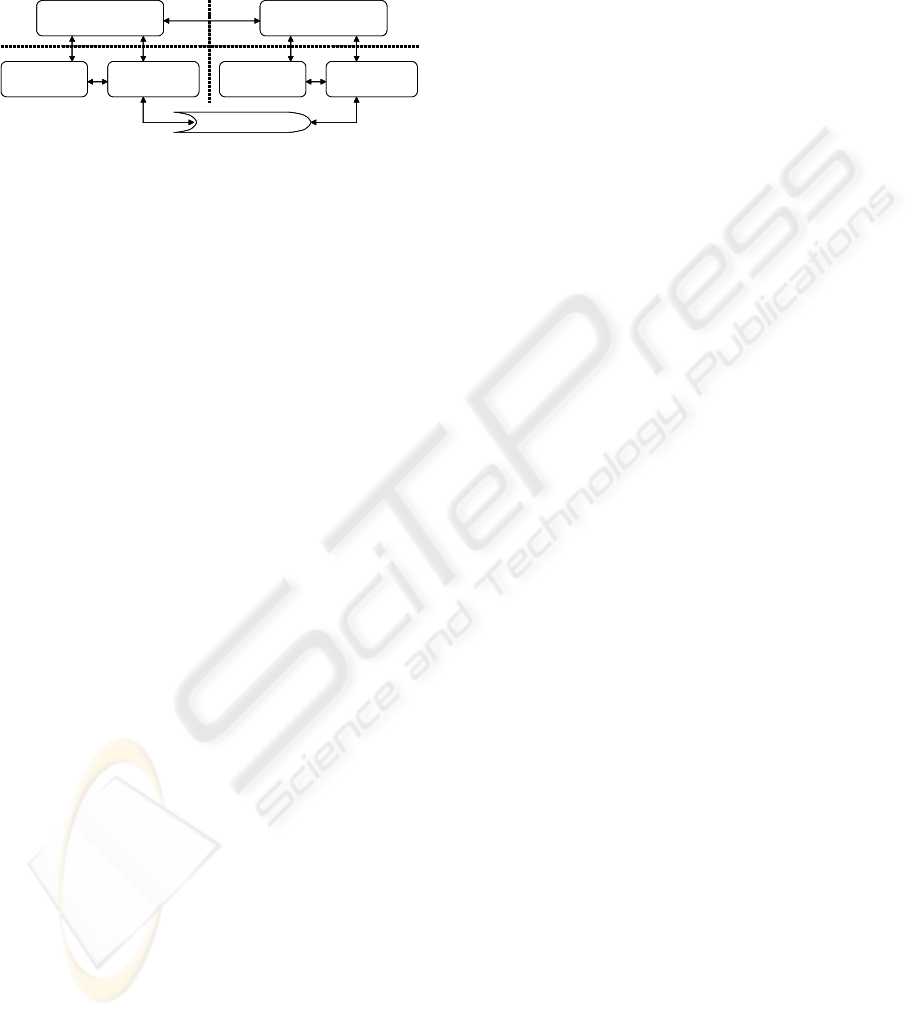

We conclude that there are two communication

gaps. The problem is illustrated in Figure 2, the

dotted lines show the communication gaps.

Business people A Business people B

IT people A IT people BIT systems A IT systems B

Network

Business people A Business people B

IT people A IT people BIT systems A IT systems B

Network

Figure 2: Two gaps in realizing B2Bi

Collaboration implies communication. Much

communication can be automated (e.g. sending

purchase orders), but communication at a meta-

level, i.e., communication about the communication,

is hard – if not impossible – to automate. As we will

see, this level of (human) communication can be

supported by architectural descriptions.

3.2 Creativity Requires

Communication among Partners

One of the most-promising challenges in the B2B

domain is the offering of Web services with a

coarse-grained functionality, i.e., services that are

composed of several smaller services. These smaller

services are then called in parallel or in sequence

and the call may be contingent on some conditions.

Note that the big service may use small services of

different companies. It is interesting to note that due

to the ubiquity of the Internet and the SOAP

standard companies with an EDI network have lost

the competitive advantage of having automated

communication, as Web services form a (cheaper)

alternative that is available to everyone (i.e. the

automation of standard processes becomes a

commodity). Competition has shifted to a higher

level: use the standards (TCP/IP and SOAP)

creatively to realize new business practices so as to

create a competitive advantage for the company!

Currently, Web services are mostly used for

information exchange. However, if the Web services

paradigm is to be the paradigm for B2Bi, it should

also allow for the realisation of business transactions

(all-or-nothing scenarios). Realising transactions in a

B2B context can get very complicated. For one

thing, the use of classic locking-protocols is not

always realistic, as companies do not like other

companies to have a lock on their data and as the

completion of transactions might take quite some

time (resulting in so-called ‘long running’ or ‘long-

lived’ transactions). Currently, much research is

being done towards the realisation of transactions in

a B2B context. Many kinds of structures are possible

for realising transactions, depending on different

degrees of trust, human relations, etcetera. We can

illustrate this with a simple example.

First, imagine a travel agency offering tourists a

BookPlaneCarAndHotelWebservice, which books an

airplane seat, a car and a hotel room, or none of

them. Upon a call of a traveller, the travel agency

would contact the three relevant partners: an airplane

booking company, a car rental company and a hotel

booking company. Availability of airplane seats and

cars may be confirmed immediately while the

confirmation of the hotel booking company may

keep the travel agency waiting for 24 hours. The

consequence of this is that the travel agency needs

the possibility to make reservations in the systems of

the airplane booking company and of the car rental

company! These reservations can be confirmed or

cancelled when the reply of the hotel booking

company arrives. This scenario clearly requires an

outstanding relationship between the companies.

There is, however, a more realistic though less

intuitive solution to the problem which requires less

trust and could be a basis for more dynamic B2Bi.

The travel agency could ask the airplane booking

company to reserve an airplane seat and to search

for a car and a hotel room if an airplane seat was

available. In this scenario, the airplane booking

company can make the seat reservation herself (so

the travel agency does not need to make reservations

in the airplane booking company’s systems!) and

sends a request to the car rental company to book a

car and to search for a hotel room. If the car rental

company has a car available, she reserves this car

herself and contacts the hotel booking company. The

latter sends a confirmation or a denial to the car

rental company, which confirms or cancels her own

reservation and informs the airplane booking

company of the result of the process. The latter then

takes appropriate actions and informs the travel

agency of the result

iii

. This whole process boils

down to serializing the transaction process we

presented first. This way, companies only make

reservations in their own systems, and wait for the

reply from the company downstream to decide

whether the reservation should be confirmed or not.

It is clear that the combination of both presented

structures offers possibilities for building bigger,

more value-adding services. While standardization is

very important and interesting at technical level (e.g.

exchanging SOAP documents), creativity remains

important when looking from a business perspective.

Creativity combined with communication (among

the right persons, such as CIOs) is indispensable to

detect ways to apply ICT in a company to get

advantages over competitors.

ICEIS 2004 - INFORMATION SYSTEMS ANALYSIS AND SPECIFICATION

334

We conclude that companies (within an EE) want

to offer useful services to each other through their

IT-systems, but that people find themselves confron-

ted with communication difficulties. Communication

about the services that should be provided, and about

the way they should be provided is very important,

as new business practices and problems may only be

revealed by discussing the issue. In our vision, the

solution to the communication problem lies in

offering every person the information he/she needs

for doing his/her part of the B2Bi job, and mapping

this information for different persons. Above this,

the information should be made persistent and

accessible. All this is exactly what we intend to do

with architectural descriptions.

4 RESOLVING THE

COMMUNICATION PROBLEMS

WITH ARCHITECTURE

DESCRIPTIONS

In what follows, we first introduce the idea of

architecture descriptions (ADs) of software-

intensive systems. Subsequently, we investigate how

architecture descriptions could be of help in a B2B

integration exercise. In this paper, it is not our goal

to show how to do Enterprise Architecture. Rather

we want to show the powers of using Enterprise

Architecture Descriptions in B2Bi exercises.

4.1 Introduction to Architecture

Descriptions

As stated, the Extended Enterprise is an enterprise

and can as such be architected. The Generalised

Enterprise Reference Architecture and Methodology

(GERAM; IFIP-IFAC Task Force, 1999) presents a

generic view of the lifecycle phases enterprises go

through. The Zachman framework and the FADEE

presented in this section can be mapped to the

GERAM.

Zachman (1987), who is considered to be a

pioneer in the realm of Enterprise Architecture,

discusses information system design by analogy to

the work steps and the representations of the

classical (building) architect and producers of

complex engineering products. The Zachman

framework relies on the fact that the description of

something depends on the perspective from which

you look at it, and on the question that was in mind

when making the description. As such, the Zachman

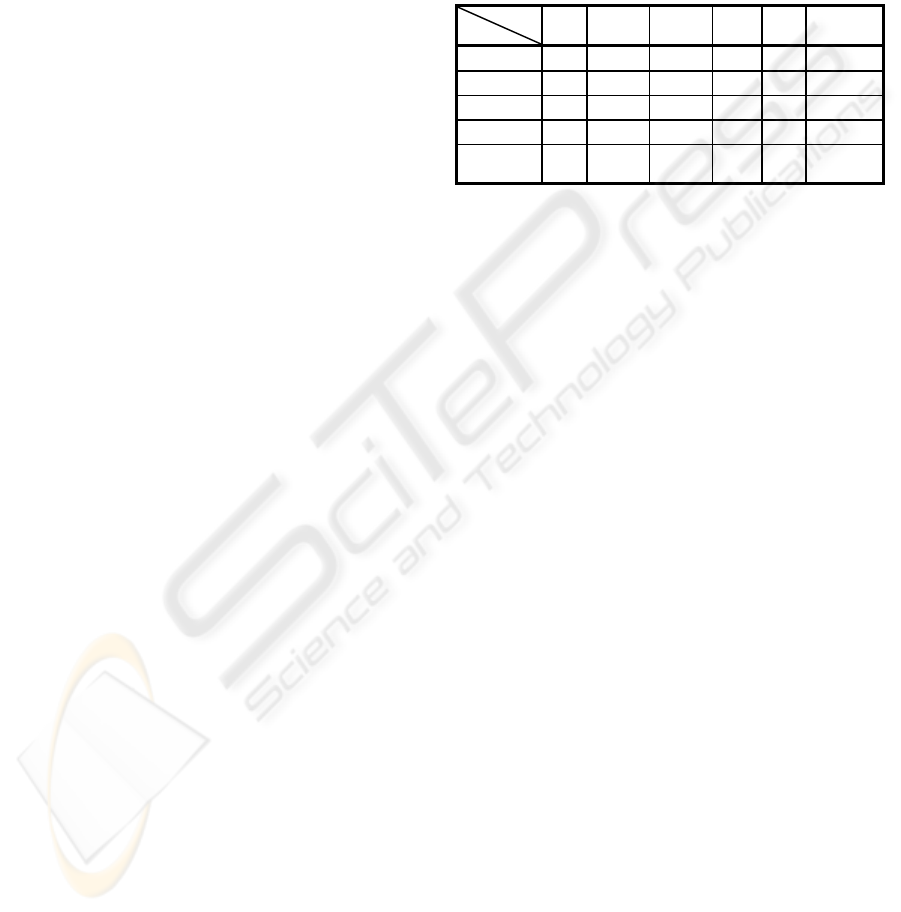

framework (as depicted in Figure 3) presents two

dimensions along which architecture descriptions

could be categorized. The first dimension (the

succession of the rows in the figure) concerns the

different perspectives of the different participants in

the systems development process (the owner’s view,

the designer’s view, the builder’s view, etc.). The

second dimension (the sequence of the columns)

deals with the six primitive English questions what,

how, where, who, when and why. It is clear that there

is not just one possible information system architect-

ture description, but a set of architecture descriptions

(ADs) that are additive and complementary.

Data

What

Function

How

Network

Where

People

Who

Time

When

Motivation

Why

Planner

Owner

Designer

Builder

Sub-

contractor

Figure 3: The Zachman Framework (Zachman, 1987)

The Zachman framework can capture all

decisions that have to be made during the systems

development process. Communicating these deci-

sions to the relevant persons is essential. Decisions

form constraints that have to be respected. It is clear

that if persons are not aware of the constraints (e.g.

because decisions were not communicated to them

or because decisions have been made too long ago),

they are taking uninformed decisions. It does not

make any sense to give people the freedom to

neglect hard constraints (see e.g. (Cook, 1996)).

Since Zachman the idea behind ADs has evolved,

producing the IEEE 1471-2000 standard on

Recommended Practice for Architectural

Description of Software-Intensive Systems. IEEE

1471-2000 defines an ‘architectural description’ as a

collection of products to document an architecture,

whereas ‘an architecture’ is defined as the

fundamental organization of a system embodied in

its components, their relationships to each other and

to the environment and the principles guiding its

design and evolution (Maier). Furthermore, a ‘view’

is defined as a description of the entire system from

the perspective of a set of related concerns. As such,

a view is composed of one or more models (Lassing

et al., 2001). Other important Enterprise Architec-

ture concepts have been defined in ISO-WD15704

(IFIP-IFAC Task Force, 1999).

Companies do not have to model all the cells in

the Zachman framework. After all, an AD is not a

goal an sich, but is a means to realise other goals.

This idea is also reflected in IEEE-1471, and in ISO-

WD15704. These state that the stakeholder concerns

should be used to justify the views, i.e., they drive

the viewpoint selection (Maier). Consequently,

before arbitrarily drawing up an AD, one should

COMMUNICATION AND ENTERPRISE ARCHITECTURE IN EXTENDED ENTERPRISE INTEGRATION

335

know what the description will be used for (see

Section 4.2).

An important issue in an Extended Enterprise

Architecture effort concerns the decision to draw up

centralized or decentralized ADs, i.e., to model all

systems at the level of the EE (one big, centralized

picture) or at the level of the individual enterprises

making up the EE (many decentralized models). In

(Goethals et al., 2004) we argued that both ideas

should be reconciled, and we developed the

Framework for the Architectural Description of the

Extended Enterprise (the FADEE). Documenting IT-

systems in accordance with the FADEE requires

every company to model the architecture of the

system from different viewpoints in a decentralized

AD (at the level of the individual enterprise), and to

model the coarse-grained, aggregated business

processes and the like (at the level of the total EE) in

a centralized AD as well. This centralized AD could

then for example describe RosettaNet PIPs, and their

link to the back-end systems (the back-end systems

themselves would only be described in the ADs of

the individual enterprises). The two types of ADs are

combined in the FADEE.

4.2 The Power of Extended

Enterprise Architecture

Descriptions

Drawing up ADs is a big effort, requiring time,

money and people. Consequently, investing in such

a process should be justifiable, i.e., the AD process

should render substantial benefits. One interesting

point to note is that ADs can be useful for EEi, but

also for EAI and dynamic B2Bi. Companies are

focusing nowadays on EAI, and consequently

drawing up ADs now could pay off three times:

during the EAI effort now, on the EEi exercise

tomorrow, and when dealing with the dynamic B2Bi

challenge later on. Of course, different levels of

integration may ask partly for different information.

By now it is clear that one complicating factor in

EEi concerns the communication about functional

and non-functional requirements, something that can

hardly be automated (at this moment at least) with

semantic markup and the like. The only way out is to

give people an incentive to communicate and to

support their communication, easing, improving,

and speeding the negotiations between companies.

Architecture models can clearly offer support for

semantics, by unambiguously defining all terms and

their relationships at different levels of abstraction.

Making a data thesaurus is in this vision not

different from making any other architecture

description of the system.

ADs are useful as a basis for discussion, which –

in our opinion – yields advantages for diverse

reasons:

Understanding the organization of the other party

is quite a difficult, though important task. By

understanding other parties, new practices,

procedures and opportunities can be revealed. This,

however, requires someone who handles the

complexity and oversees the total domain (at an

appropriate level of abstraction). ADs are a good

means to handle such complexity by making

interesting abstractions. Above this, ADs can serve

as the basis for a brainstorming-session.

Service Level Agreements (SLAs) could be

negotiated on the basis of the ADs. After all,

formulating SLAs also requires a translation of

business requirements into technical requirements

and technical measures. Note that internal SLAs are

often deployed in order to manage the expectations

of service users (see for example (Koch, 1998)).

People all too often expect too much from IT, and

this may also be the painful truth in an EE.

An AD can be used to inform, guide and

constrain decisions, especially those related to IT

investments (CIO Council, 2001). ADs can be a

facilitator for realizing B2Bi, as they ease the

adaptation of the architecture. After all, it is easier to

manage something you know well! An AD contains

much valuable information for making decisions on

investments and for system development. Note that it

is good practice to evaluate the proposed architect-

ture before getting into development. Clements et al.

(2002) state that, although architecture evaluation is

almost never included as a standard part of any

development process, evaluating the architecture

upfront is an important and inexpensive task. By

making issues explicit in an AD, problems can be

detected early on. One should not be making

implicit assumptions about functionality (especially

not in the global economy, where customs may

differ from partner to partner!). Note that it is still

very hard to test and validate choreographies of

services. By discussing difficult issues upfront,

many problems can be avoided. Also note that it is

clear that the sooner problems are noticed in the

software development process, the lower the costs of

resolving them (Boehm, 1981).

Furthermore, the concept of ADs could prove

useful for the practice of more dynamic EEi too.

That is, the AD solution has built-in functional

scalability. After all, some ADs of the systems could

be made accessible to third parties, so they could

find and understand the services a company is

offering. Also, ADs might be made executable (for

example to change business processes through

models of the processes). Please note that the

ICEIS 2004 - INFORMATION SYSTEMS ANALYSIS AND SPECIFICATION

336

GERAM also mentions ‘Enterprise Model Execution

and Integration Services’.

5 CONCLUSIONS

We have identified the communication problems

that exist in the Web services world, and we have

proposed a means to solve this problem. While ADs

have been used in the past in the context of separate

legal entities, they now also seem interesting in the

case of B2Bi.

Providing Web services is not just an IT topic,

but also a business matter. The design of Web

services requires a lot of communication between

persons with different backgrounds, capacity and

vocabularies. To support this communication,

architecture descriptions could be very helpful.

Above this, it is clear that documenting IT systems

is a very important prerequisite to come to a

manageable and maintainable IT infrastructure.

Also, in the future, code may be generated from the

models that describe the system; and dynamic B2B

integration could be based on architecture

descriptions represented in an Architecture Markup

Language (AML, such as ADML and MLAD) that

incorporates concepts from semantic web research.

Therefore, we believe that semantic web efforts

(such as RDF and DAML), Web service

standardization efforts (as BPEL4WS, BPML,

etcetera), and AML initiatives should go hand in

hand. We conclude that Enterprise Architecture

Descriptions could become invaluable, also (and

especially) in the case of B2Bi.

REFERENCES

Boehm B., Software Engineering Economics, Prentice-

Hall Englewood Cliffs, 1981, pp 767.

CIO Council, 1999. Federal Enterprise Architecture

Framework version 1.1, pp 80. Retrieved from

www.cio.gov/documents/fedarch1.pdf (visited on

29/1/2003).

CIO Council, 2001. A Practical Guide to Federal

Enterprise Architecture. Retrieved from

www.cio.gov/documents/bpeaguide.pdf (visited on

29/1/2003).

Clements P., Kazman R., Klein M., 2002. Evaluating

software architectures, Addison-Wesley, pp302.

Cook M., 1996. Building Enterprise Information

Architectures, Prentice-Hall, pp 179.

Department of the Treasury, Chief Information Officer

Council, July 2000. Treasury Enterprise Architecture

Framework, Version 1, pp. 164. Retrieved from

http://ustreasury.mondosearch.com/cgi-

bin/MsmGo.exe?grab_id=49270800&EXTRA_ARG=

IMAGE.

Frankel D., Parodi J., 2002. Using Model-Driven

Architecture to Develop Web Services. Retrieved from

http://www.omg.org/attachments/pdf/WSMDA.pdf

(visited on 29/1/2003).

IFIP-IFAC Task Force, 1999. GERAM: Generalised

Enterprise Reference Architecture and Methodology,

Version 1.6.3. Retrieved from

http://www.cit.gu.edu.au/~bernus/taskforce/geram/ver

sions/geram1-6-3/GERAMv1.6.3.pdf (visited on

29/1/2004).

Goethals F., Lemahieu W., Vandenbulcke J., 2003.

Identifying Web Service Integration Challenges,

IRMA conference proceedings.

Goethals F., Vandenbulcke J., Lemahieu W., 2004.

Developing the Extended Enterprise with the FADEE,

ACM SAC 2004 conference proceedings (to appear).

Koch C., November 15, 1998. Put IT in writing, CIO

Magazine. Retrieved from

http://www.cio.com/archive/111598/sla_content.html

(visited on 29/1/2003).

Lassing N., Rijsenbrij D., van Vliet H., September 2001.

Zicht op aanpasbaarheid, Informatie, pp 30-36.

Linthicum D.,2000. B2B Application Integration: e-

Business-Enable Your Enterprise, pp 464, Addison

Wesley.

Maier M., The IEEE 1471-2000 Standard - Architecture

Views and Viewpoints. Retrieved from

www.opengroup.org/architecture/togaf/agenda/

0107aust/presents/maier_1471.pdf

.

Podolny J., Page, K., 1998. “Network forms of

organization.” ARS 24 (1998):57-76.

Pollock J., 2002. Dirty Little Secret: It’s a Matter of

Semantics. Retrieved from

http://eai.ebizq.net/str/pollock_2a.html (visited on

29/1/2003).

van der Lans R., 2002. Web services voor EAI en B2B.

Workshop SAI, 14/10/2002.

Zachman J.,1987. A framework for information systems

architecture, IBM Systems Journal, Vol. 26, No.3, pp

276-292.

i

This paper has been written as part of the ‘SAP-leerstoel’-project

on ‘Extended Enterprise Infrastructures’ sponsored by SAP

Belgium.

ii

Consequently there are two communication gaps. This may

seem evident, but neglecting these communication gaps lies at

the basis of a substantial number of project failures.

iii

The problem we have tackled is fundamental and is all too often

neglected! The fact is that companies do not like other

companies to make reservations of which the confirmation only

depends on the intentions of the company making the

reservation. The commitment that should be part of the

reservation is actually no commitment at all as the confirmation

only depends on the wishes of the other party!

COMMUNICATION AND ENTERPRISE ARCHITECTURE IN EXTENDED ENTERPRISE INTEGRATION

337