AN ANALYSIS OF VARIATION IN TEACHING EFFORT

ACROSS TASKS IN ONLINE AND TRADITIONAL COURSES

Gregory W. Hislop

College of Information Science and Technology, Drexel University, 3141 Chestnut St., Philadelipia, PA, U.S.A.

Heidi J.C. Ellis

Department of Engineering and Science,Rensselaer at Hartford, 275 Windsor St. Hartford, CT, U.S.A.

Keywords: Online education, Instructor time, Asynchronous Learning Networks, Higher Education

Abstract: As the role of the internet and internet technologies continues

to grow in pace with the rapid growth of

online education, faculty activities and tasks are changing to adapt to this increase in web-based instruction.

However, little measurable evidence exists to characterize the nature of the differences in teaching effort

required for online versus traditional courses. This paper reports on the results of a quantitative study of

instructor use of time which investigates not only total time expended, but also examines differences in

types of effort. The basis of the study is a comparison of seven comparable pairs of online and traditional

course sections where instructors recorded time spent during course instruction for the seven pairs. This

paper discusses relevant related work, presents the study motivation and design, discusses how teaching

effort varies across different tasks between online and traditional courses, and presents thoughts for future

research. The results of this study indicate that instructors of online courses spend more time on direct

interaction with students when compared to instructors of traditional courses, but spend less time on other

activities such as grading and materials preparation.

1 INTRODUCTION

The use of the Internet as a distance education

medium continues to grow and many institutions

offer Internet courses using asynchronous,

computer-based instruction. This growth is

changing the faculty role and requires a shift in the

expenditure of time as faculty teach online.

Few quantitative studies exist on faculty use and

d

istribution of time when teaching online courses. A

perceived increase in level of interactivity between

faculty and students was observed by Hiltz and

Turroff (Hiltz & Turroff, 2002), Young (Young,

2002), and Salmon (Salmon, 2002). Based on

nineteen studies performed at NJIT, Hiltz and Turoff

recommend that in order to build student confidence

in an online course, faculty should be online

frequently. In addition, Hiltz and Turoff emphasize

the need for frequent interactions with students early

in the semester to establish a foundation of trust, and

also indicate that this structure of confidence should

be preserved and strengthened by maintaining a high

level of interaction throughout the semester.

Young (Young, 2002) comments on the changes

requ

ired by faculty when e-teaching in order to meet

students’ expectations of immediate response to

questions and requests for interaction. In fact, this

increased pattern of interaction is reinforced by the

structure imposed by some academic institutions that

requires instructors to respond to student email or

bulletin board postings within 24-48 hours. Indeed,

in her keynote address to the 2002 EduCAT Summit,

Dr. Gilly Salmon (Salmon, 2002) emphasized that

the use of time in online courses is more flexible

than in courses taught in a traditional mode and that

instructors of online courses should expect to adapt

their schedules to the online mode of education.

Other researchers have also noted increased

interactivity in online courses (Hislop & Atwood,

2000; Hartman, Dziuban & Moskal, 2000; Schifter,

2000a; Schifter, 2000b).

The major drawback to the studies discussed

ab

ove is the use of a survey or interview-based

approach that relies on faculty opinions and

202

W. Hislop G. and J. C. Ellis H. (2004).

AN ANALYSIS OF VARIATION IN TEACHING EFFORT ACROSS TASKS IN ONLINE AND TRADITIONAL COURSES.

In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, pages 202-207

DOI: 10.5220/0002625002020207

Copyright

c

SciTePress

observations rather than measurable data. The most

useful research on faculty time spent on various

teaching tasks for online and traditional courses

come from studies in which faculty measured time

spent on various activities required to deliver an

online course. DiBiase (DiBiase, 2000) investigated

the time spent on various activity categories in

teaching two similar geography courses, one taught

online and the other taught using a traditional, face-

to-face format. However, while DiBiase normalized

the total time figure on a per student basis to provide

an accurate picture of the total amount of time

required to teach online and traditional courses, the

study did not present normalized figures for the task

categories, making it difficult to clearly ascertain the

difference in effort expended across tasks between

the two modes of delivery. Visser (Visser, 2002)

performed a similar study of faculty effort using a

more detailed categorization of tasks, but also did

not normalize the time figures for task categories.

This paper reports on a study involving the

detailed recording of instructor time in comparable

online and traditional course sections to support a

comparison of the distribution of faculty time over

tasks between the two modes of delivery. Initial

results of the study which indicate little significant

difference between the total time required to teach

online and traditional courses are reported in

(Hislop, 2001) while details on the study

environment and approach are provided in (Hislop &

Ellis, 2004). This paper provides more detailed data

on faculty time distribution across different teaching

activities, using quantitative data to clarify how

faculty time is used in teaching online courses.

2 STUDY APPROACH

In this study, participants categorized their teaching-

related activities, providing a basis for investigating

the nature and characteristics of how teaching effort

varies between online and traditional courses. We

know that when teaching an online course, the

traditional face-to-face activities such as lecture and

informal discussion with students will be replaced

by online activities. But an analysis of effort

distributed across specific activities will allow us to

compare the amount of time taken by those

replacement activities. We will also be able to look

for changes in time spent on tasks common to the

two delivery modes such as grading.

The study was conducted using seven pairs of

comparable sections of graduate courses in

information systems and software engineering taught

in a U.S. institution. The typical student taking one

of these courses was a technically savvy, full-time

working professional. All courses used in the study

were mature courses and all factors of online

sections of the course (e.g., class size maximums,

course content, etc.) were designed to be as

equivalent to the traditional sections as possible.

The online classes were completely online and

generally asynchronous, with the exception that

some courses may have required students to attend

weekly discussion at a prescribed time. The delivery

platform was a custom application built using Lotus

Notes and the courses were accessible over the Web

using either a Notes client or a Web browser.

(Hislop, 2000) contains additional information about

the online environment.

This study measured teaching for pairs of

sections of the same course, one taught online and

one taught face-to-face, both taught by the same

instructor. The sections were taught in the same or

successive terms, and with no major changes in

course materials between the two offerings. The

instructors for the course sections were all

experienced teachers and all sections were taught

without the benefit of teaching assistants or other

types of support. In order to ensure participation,

instructors were paid for completing the logging task

for a pair of course sections and time was only

logged during the 11 weeks of the term in which the

class section ran. Instructors logged their time using

the following categories: Administration,

Discussion, Email, Grading, Lecture, Materials,

Other, Phone, Preparation, Talk, and Technology.

The study results reported in this paper attempt

to provide a partial answer to the question of what

differences exist in the types of faculty effort

expended for online and traditional classes. In

particular, the results reported in this paper attempt

to address two main questions:

1. What are the differences in instructor time

spent on various teaching tasks between online and

traditional sections?

2. Within a particular mode of delivery, how

does instructor time spent on specific tasks differ

between more and less time-efficient instructors

using that particular mode of delivery?

Section 3 provides a high-level summary of the

total effort results and discusses each of these

research questions in separate subsections.

3 DATA ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

The study produced complete time logs for seven

pairs of course sections. As reported in (Hislop &

Ellis, 2004) which describes the investigation into

total effort and effort over time, the total time logged

for online sections was 737 hours, and 814 hours

AN ANALYSIS OF VARIATION IN TEACHING EFFORT ACROSS TASKS IN ONLINE AND TRADITIONAL

COURSES

203

were logged for the traditional sections. The average

size of the online classes was 19.3, while the

traditional class’ average was 26.0 and the average

for the entire set was 22.6. These figures represent

an approximately 25% difference in average class

size between traditional and online sections. The

commonly held assumption that teaching has

economy of scale was supported by the findings in

this study as when the total effort figures were

normalized on a per student basis, the average

number of hours spent per online student was 6.26,

while 6.17 hours were spent per traditional student.

3.1 Task Differences

The categorization of time enumerated above

provides a basis for a more in depth examination of

how teaching effort varies across different tasks

between online and traditional courses. An analysis

of cataloged effort allows us to see what online

activities replace the traditional face-to-face

activities such as lecture and informal discussion, as

well as allowing us to look for differences in time

spent on tasks common to the two delivery modes

such as grading.

Since a commonly held opinion is that e-teaching

requires an increased level of interactivity between

instructor and student, we generally grouped the

activity categories based on their interactivity

requirements. The activity by category (normalized

per student) is presented in Tables 1 and 2, where

Table 1 contains all the activities that involve

interaction between the instructor and students, and

Table 2 contains all the activities that do not involve

student interaction. We can begin with a general

observation that several of the categories across the

two tables do not account for much time. In

particular, Phone, Talk, Technology, and Other

taken together account for only about 5 % of the

total time logged. The remaining categories

(Discussion, Email, Lecture, Grading, Materials, and

Preparation) account for 95% of the activity.

Based on the data presented in Table 2, we make

the following observations. First, the subtotals

indicate that in the online class, the instructor spends

more time on activities that involve interaction with

students than the instructor does in a traditional

section. This increased interactivity for online

sections fits the intention that online classes in this

study will emphasize transfer of ideas among

participants. The observed enhanced communication

also provides further support for prior survey work

that indicates that faculty and students both feel that

they interact more in online classes than they would

in a traditional class (Turroff, Hiltz & Turroff, 2002;

Young, 2002; Salmon, 2002; Hartman, Dziuban &

Moskal, 2000; Schifter, 2000a; Schifter, 2000b).

Table 1: Hours per Student per Section - Student

Interaction Activities

Online Traditional

Discussion 2.34 0.00

Email 0.40 0.51

Lecture 0.00 1.59

Phone 0.06 0.04

Talk 0.00 0.27

Subtotal 2.79 2.42

Table 2: Hours per Student per Section - Other Activities

Online Traditional

Administration 0.03 0.06

Grading 1.77 1.82

Materials 1.17 0.78

Preparation 0.37 1.02

Technology 0.12 0.00

Other 0.03 0.02

Subtotal 3.48 3.75

An examination of the columns of Table 1 shows

the expected substitution of Discussion activity in

online sections for Lecture and Talk activities in the

traditional sections. Perhaps more interesting are the

results for the two categories of Email and Phone.

For the Email category, it is noteworthy that both

delivery modes show about the same time expended

per student, with the traditional mode of delivery

even being a bit higher than the online mode. This

apparent equivalency in time spent on email for both

modes of delivery provides an interesting example

of the ways in which the online and traditional

delivery formats are likely to increasingly merge

over time. The time logged for the Phone category

is also approximately equivalent for both modes, and

is not very large. It is interesting to note that Phone

time is smaller than Email, perhaps reflecting the

value of asynchronous communication in a graduate

class environment.

Inspecting the non-interactive categories shown

in Table 2, the classes of Administration,

Technology, and Other represent only small amounts

of time. The Technology time is important since it

shows that technical problems were not a significant

factor for the instructors in these online classes.

ICEIS 2004 - SOFTWARE AGENTS AND INTERNET COMPUTING

204

As shown in Table 2, instructor time spent

grading is roughly comparable for both delivery

modes. This uniformity of effort across the two

modes is actually somewhat surprising since

instructors often talk about the increased number of

steps required to deal with assignments that are

submitted and returned online rather than on paper

in a traditional setting.

Finally, Table 2 shows some variation by mode

in time spent on Materials and Preparation. The

higher time figure for the Materials category for the

online sections probably reflects the fact that the

online versions of the courses in this study are much

newer than the traditional versions.

The Materials time difference may also reflect a

slower process for creating work items like handouts

online due to the relative immaturity of the

productivity tools in online environments. We

would naturally expect the Preparation time online

to be lower since there are no formal class meetings.

Overall, the investigation into the specific types

of effort expended by instructors of online and

traditional courses revealed a higher degree of

interactivity in online courses, and the data results

demonstrated an expected trade-off between a higher

Materials time figure for traditional courses and a

higher Preparation time figure for online sections.

One somewhat surprising observation about the type

of effort expended by instructors of online and

traditional courses is that instructors appear to spend

a nearly equivalent amount of time in email and

grading activities for both online and traditional

courses.

3.1 Efficiency Differences by Mode

In order to get a clearer picture of faculty behavior

in both online and traditional courses, we grouped

the seven section pairs based on efficiency of mode

of delivery. (Note that we use the term efficiency

here to mean time usage.) In other words, we

grouped together the four section pairs in which

faculty expended less time on the online sections

(online-efficient) and we grouped together the three

section pairs in which faculty expended less time on

the traditional sections (traditional-efficient). We

then normalized the data on a per student basis to

investigate the differences in time expended by the

two sets of instructors to try to answer the question

“what are the differences in tasks between more and

less time-efficient instructors using a particular

mode of delivery?”

Upon analyzing the total time expended by

instructors when teaching traditional sections, we

observed that there was little difference between the

amount of time expended by instructors in the

online-efficient group, with an average of 6.12 hours

spent per student per section, and the effort used by

instructors in the traditional-efficient group who

expended an average of 6.23 hours per student per

section. These results indicate very little variation in

instructor time expenditure across the range of

sections taught using a traditional mode of delivery,

regardless of instructor efficiency with respect to

mode of delivery. One logical conclusion that could

be made about these consistent results is that

instructors are more familiar with the traditional

mode of delivery and have already achieved similar

levels of efficiency in teaching face-to-face course

sections.

A more substantial difference in time expended

on online courses was observed when the data from

the online-efficient and traditional-efficient groups

of instructors were compared for online and

traditional sections. Table 3 shows the time

expended on both online and traditional courses by

the online-efficient and traditional-efficient groups.

The online-efficient instructors took 4.66 hours per

student to teach the online sections, while the

traditional-efficient instructors took 8.4 hours per

student to teach the online sections. As previously

noted, all sections had negligible activity in the

Administration and Other categories so these

categories were omitted from Table 3.

One major difference between the two groups

that can be observed from Table 3 is the disparity in

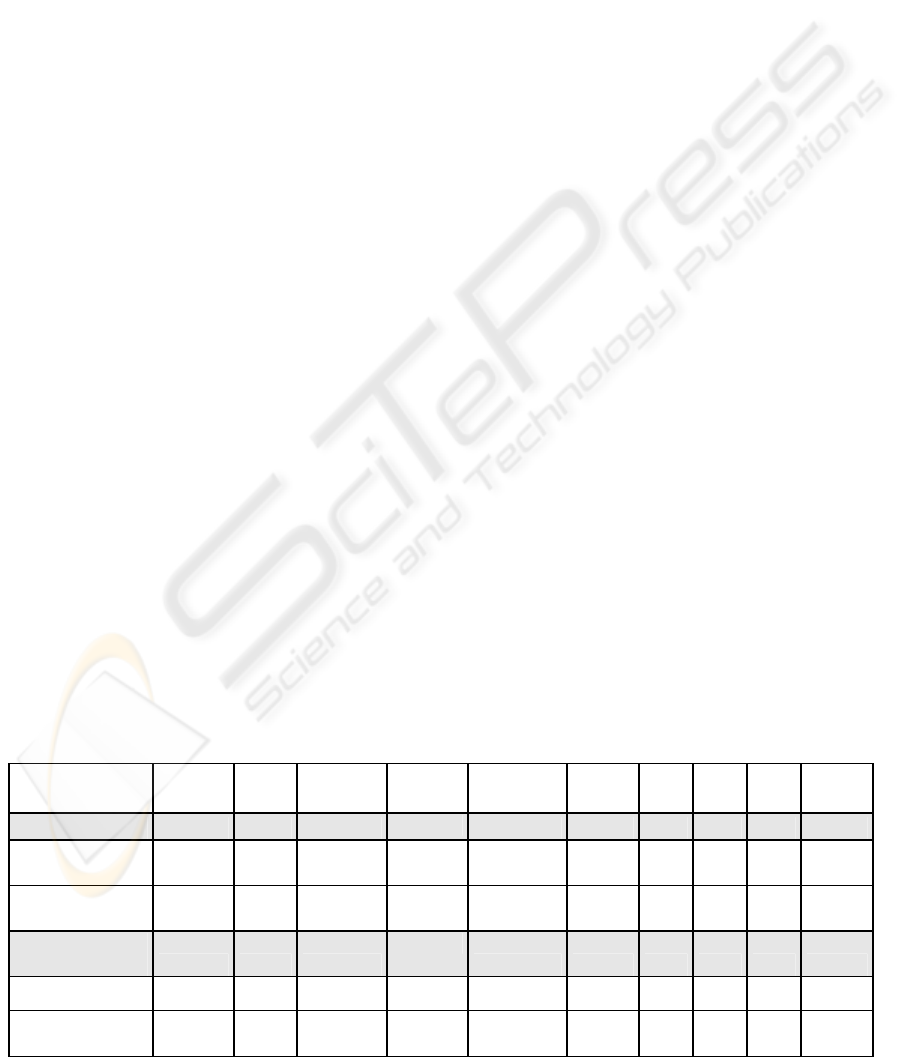

Table 3 - Hours per Student per Section for Online and Traditional Sections

Discuss Email Grading Lecture Materials Phone Prep Talk Tech

Grand

Total

Online Courses

Online-Efficient 1.70 0.44 1.10

0.00 1.02 0.06 0.25

0.00 0.05 4.66

Traditional-

Efficient

3.19

0.33

2.66

0.00

1.36 0.06 0.51

0.00

0.21 8.40

Traditional

Courses

Online-Efficient 0.00 0.59 1.69 1.55 0.82 0.08 0.90 0.39 0.00 6.12

Traditional-

Efficient

0.00 0.42 1.99

1.65

0.72 0.00 1.29

0.10

0.00 6.23

AN ANALYSIS OF VARIATION IN TEACHING EFFORT ACROSS TASKS IN ONLINE AND TRADITIONAL

COURSES

205

the Discussion figures for the online sections. The

instructors in the online-efficient group spent less

time than their traditional-efficient counterparts.

While the online-efficient group did spend 1/3 more

time on email than the traditional-efficient group,

this difference is not large enough to account for the

53% increase in Discussion time spent by the

traditional-efficient group.

Another major dissimilarity in effort can be

observed in the Grading category for the online

sections where instructors in the traditional-efficient

group spent more than twice the time grading as did

the online-efficient instructors. Several reasons may

give rise to this difference. First, the traditional-

efficient instructors may be taking extra steps when

grading online (e.g., detaching email attachments,

printing assignments, returning hard copy to

students, etc.) as opposed to simply grading directly

online. Second, the difference could be the result of

instructors struggling to learn how to grade online.

The efficiency effect might also be a result of the

fact that some instructors are learning how to grade

online more efficiently than grading using a

traditional approach.

Table 3 also shows increases in instructor time

for the Materials category in the traditional-efficient

group when teaching online sections. In addition, the

traditional-efficient group also shows significant

increases in the Preparation category when teaching

both online and traditional sections. Possible

reasons for these differences include that the

instructors in the traditional-efficient group may be

less experienced in teaching online or struggling

more with the online environment. Another

possibility is that the instructors in the traditional-

efficient group may be struggling with how to

represent the course online.

The difference in the Technology category for

online courses is a small number but represents a

substantial difference in percentage of effort. As

shown in Table 3, the traditional-efficient group of

instructors spent four times the amount of effort

when teaching online as the online-efficient group.

This small difference may be an indicator that the

instructors who are less efficient teaching using the

online mode of delivery are also less technically

capable overall.

One interesting difference occurred in the Talk

category for traditional courses where the online-

efficient instructors appear to spend almost four

times the amount of time talking with students on a

per student basis than the traditional-efficient

instructors. In addition, the online-efficient

instructors also logged more time in the Phone

category than their traditional-efficient counterparts

when teaching using a traditional mode of delivery.

Overall, when comparing online sections where

instructors were more efficient to online sections

where instructors were less efficient, there is a wider

variance in the time expended than when comparing

the efficiency of the groups of instructors when

teaching traditional course sections. Indeed, the

traditional-efficient group of instructors spent almost

double the amount of time on various tasks

associated with teaching online as compared to their

online-efficient counterparts. Possible reasons for

this difference range from changes in course

representation, grading, and interaction approaches

used in online courses to the technical abilities of the

instructor. An examination of instructor evaluations

and learning outcomes might provide additional

reasons for this difference.

The total time figures for the online-efficient and

traditional-efficient groups of instructors teaching

using a traditional mode of delivery are much closer

than when using an online mode of delivery.

However, it should be noted that the online-efficient

group still uses slightly less time per student when

teaching a traditional course.

4 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORK

The results of this quantitative investigation into the

differences in instructor time spent on teaching tasks

have highlighted several significant differences

between time expenditures by instructors of online

and traditional courses. Overall, the results reinforce

the perception that online instructors engage in more

interactive endeavors with their students than do

instructors of traditional courses. Also of interest

was the finding that instructors spend approximately

the same amount of effort on email, regardless of

mode of course delivery. The amount of time spent

by instructors grading was roughly comparable for

both the online and traditional delivery modes.

A finer grained examination of the data

scrutinized instructor behavior patterns by grouping

instructors into groups based on the mode of

instruction in which they were efficient (i.e., spent

less time). When efficiency mode of the instructor

was factored in, the widest variation of effort was

seen in online sections with instructors efficient in

online teaching spending significantly less time on

grading, materials, preparation, and discussion

activities than instructors who were more efficient

using the traditional mode of teaching. As could be

expected, the online-efficient and the traditional-

efficient groups of instructors spent approximately

the same amount of time teaching a traditional

course.

ICEIS 2004 - SOFTWARE AGENTS AND INTERNET COMPUTING

206

The results of this study suggest several areas for

future research. The obvious future step would be to

expand the study to include additional pairs of

course sections. This additional data would provide

a broader base of support for conclusions drawn by

this research. In addition, the inclusion of data from

instructor evaluations and learning outcomes would

help identify root causes of the differences in time

expenditure between online and traditional

instructors. A third area of investigation is the

impact of instructor attitude on pattern of effort as an

instructor’s mindset may have a significant influence

on how they deliver a course. Lastly, given that

teaching an online course requires a certain level of

technical knowledge, an investigation of the effect

of instructor technical expertise on pattern of effort

might also provide insight into the differences in

time expended by instructors of online and

traditional courses.

REFERENCES

DiBiase, D., 2000. Is distance teaching more work or less?

The American Journal of Distance Education, Vol. 14,

No. 3.

Hartman, J., Dziuban, C., & Moskal, P., 2000. Faculty

satisfaction in ALNs: A dependent or independent

variable? Journal of ALN, Vol. 4 Iss. 3.

Hiltz, S. R., & Turoff, M., 2002. What makes learning

networks effective? CACM, Vol. 45, No. 4.

Hislop, G. W. & Atwood, M. E., 2000. ALN teaching as

routine faculty workload. Journal of ALN, (4)3.

Hislop, G. W., 2000. Working professionals as part-time

online learners. Journal of ALN, (4)2.

Hislop, G. W., 2001. Does teaching online take more

time? Proc. of 31st ASEE/IEEE Frontiers in

Education Conf. Reno, NV.

Hislop, G. W. & Ellis H. J. C., 2004. A study of faculty

effort in online teaching, to be published in: The

Journal of Higher Education, (7)1.

Salmon, G., 2002. Hearts, minds and screens: Taming the

future. [Keynote speech] EduCAT Summit, Innovation

in e-Education, Hamilton, New Zealand,

Schifter, C.C., 2000a. Faculty participation in

asynchronous learning networks: a case study of

motivating and inhibiting factors. Journal of the ALN,

(4)1.

Schifter, C. C., 2000b. Compensation models in distance

education. The Online Journal of Distance Learning

Administration, (III)1.

Visser, J. A., 2000. Faculty work in developing and

teaching web-based distance courses: A case study of

time and effort. The American Journal of Distance

Education, (14)3.

Young, J. R., 2002. The 24-hour professor: Online

teaching redefines faculty members’ schedules, duties,

and relationships with students. The Chronicle of

Higher Education, (48)38.

AN ANALYSIS OF VARIATION IN TEACHING EFFORT ACROSS TASKS IN ONLINE AND TRADITIONAL

COURSES

207