ORGANISATIONAL LEARNING

- foundational roots for design for complexity

Angela Nobre

Escola Superior de Ciências Empresariais,Instituto Politécnico de Setúbal, Campus do IPS, Estefanilha, 2914-503Setúbal,

Portugal

Keywords: Organisational learning, organisational design, complexity, sociotechnical systems, systems theory, social

systems, and appreciative inquiry.

Abstract: This paper presents an overview of the field of organisational learning and claims that its foundational roots

still have to be further developed and explored. This critique points to the potential of sociothecnical

systems, complex systems theory and appreciative inquiry as building blocks from which an effective

organisational learning design can emerge. The current challenges faced by organisations are related to the

complexity of the knowledge economy. These challenges need to be answered by an organisational

development strategy that incorporates competitive issues, corporate governance and sustainability

concerns.

1 INTRODUCTION

We have entered a new era in the evolution of

organisational life. There are immense forces of

change present simultaneously: technology

development, societal change, global markets and an

increased complexity and volatility of organisational

environments. New terminology captures the

changes in work-life reality: post-industrial society,

the information revolution, the post-capital society,

and the knowledge age. Kearmally (1999) refers to

the knowledge economy of the information era. The

information era and the knowledge economy imply

the need for a learning society.

At organisational level the issue of learning may

b

e interpreted as the overall adaptation and

development which is necessary in order to profit

form the challenges and opportunities of the new

environment. Though we might not be able to fully

comprehend and grasp the magnitude of the

changes, organisations and managers are struggling

to find the balance between economic performance,

managing business transformation, and business and

human sustainability.

Organisational learning has developed from

man

y roots and threads of thought. As the field

matures it is critical that some of the baseline

concepts are not overlooked. In tune with

hierarchical systems theory, it is necessary to

distinguish those issues which have a structuring

effect over the others thus allowing for an overall

consistent development. Hierarchies exist because

not everything has the same importance, which does

not imply that we need hierarchical organisations as

we know them. Prescriptive, simplistic and

mechanistic forms of interpreting and promoting

organisational learning are of less consequence than

exploratory, complex and interpretative approaches.

In order to envision what paths will lead us in what

directions it is important to consider the criteria of

what might bring us to a situation where the greatest

diversity of possibilities may materialise, i.e. how

may we open and keep open the complex systems in

which we are immersed.

The current paper focus on some of the origins of

or

ganisational learning and aims at pointing at an

approach which may help twenty first century

organisations to deal with the daily struggle of

bridging theory and practice, our intentions and our

actions, and what the organisation as a whole

officially states that it stands for and how that

materialises into current reality.

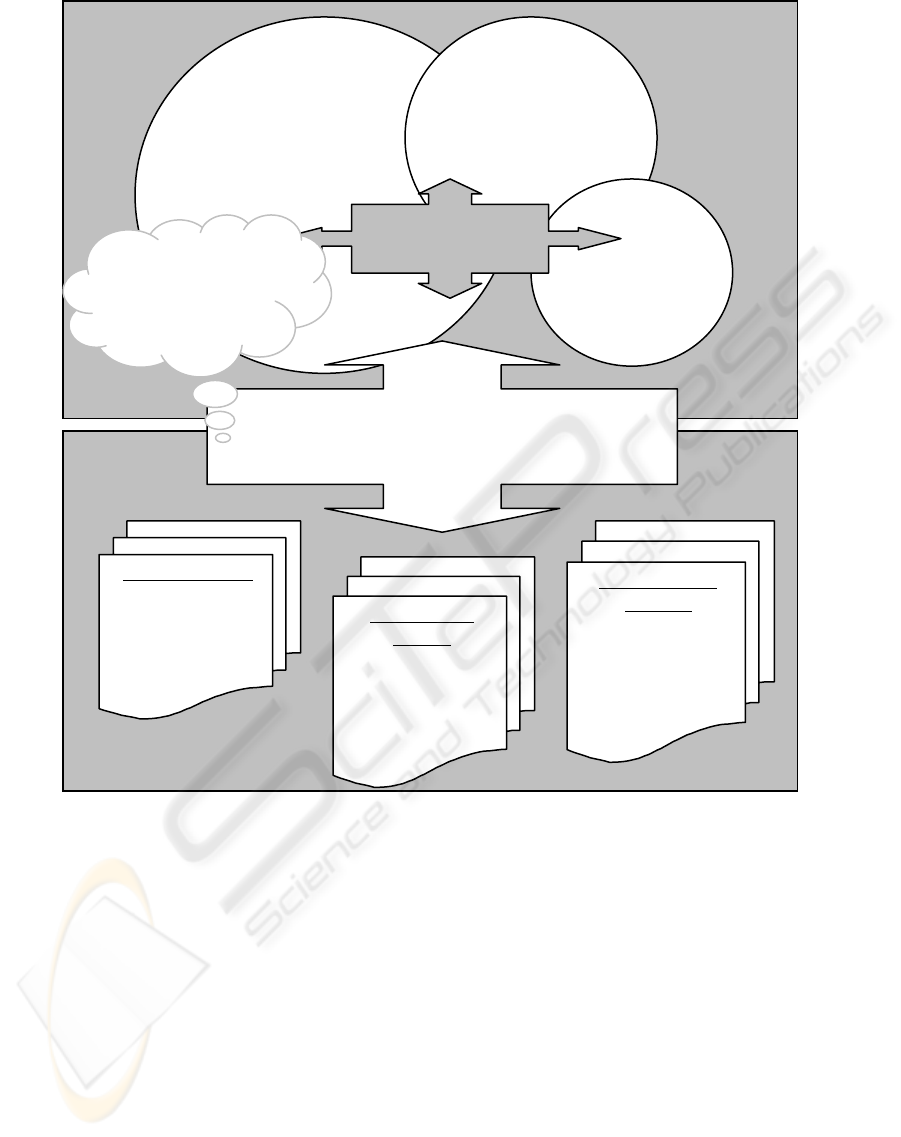

Figure 1 presents a general overview of the key

conce

pts and theories developed in the paper.

85

Nobre A. (2004).

ORGANISATIONAL LEARNING - foundational roots for design for complexity.

In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, pages 85-93

DOI: 10.5220/0002652400850093

Copyright

c

SciTePress

Internal

organisational

settings

External

Organisational

Environment

Figure 1 – The need to reinvent the foundations of Organisational Learning

2 ORGANISATIONAL LEARNING

DEVELOPMENT

There has been a continual effort to devise

managerial innovations able to deal with the

challenges posed by the organisations’ environment

changes. Examples of these efforts are:

empowerment, business process reenginering, self-

managed teams, sociotechnical systems redesign,

and total quality management.

Some authors comment that often, the

application of these methods has been linked to a

fashion or a management fad motivation

(Abrahamson, 1996, 1999; Gibson and Tesone,

2001). There is a growing recognition that these

methods too often failed to deliver their promises

(Beer, 2000). Lillrank et al (2001) claim that the

impacts of the continuous improvement methods,

tools, and processes that aim to help organisations to

enhance their productivity, quality, and worker’s

quality of working life are usually short lived.

Pursuer and Cabana (1998) state that the problems

with the reduced effectiveness of these

methodologies, when applied in real life situations,

is due to their link, in practice, with the concepts of

traditional hierarchical organisations and industrial

age notions of management.

In response to the complexity and uncertainty of

a turbulent environment, the learning organisation

appears as an effort to radically develop a

continuous innovative and adaptive capacity.

Organisational learning developed from the

methodologies already mentioned and also from the

early pioneering experiments with self-managing

and learning work-systems conducted in early action

Individuals

COMPLEXITY

ORGANISATIONAL LEARNING

> continuous improvement <

=> Organisational Development <=

Challenge:

to reinvent the

foundations of OL

Systems Theory

holistic whole +

parts + boundary

Sociotechnical

Systems

work task +

technology +

social organisation

Appreciative

Inquiry

managing

relationships +

reflection

ICEIS 2004 - INFORMATION SYSTEMS ANALYSIS AND SPECIFICATION

86

research projects such as the sociotechnical work in

British and coal mines and Scandinavia (Shani and

Docherty, 2003; Obholzer and Roberts, 1994).

Marquardt and Reynolds (1996) published a

comprehensive list of companies which have

engaged in some activities around creating a

learning organisation.

The conceptualisation of organisational learning

is complex and its origins cannot be pin-pointed in a

precise way, in part because this is a new

management discipline and consequently its

conceptual basis are still being developed in a

continuous way. Yet there is a set of contemporary

theories which help us to distinguish early

influences, such as: business strategy theory,

resource-based view of the firm, behavioural theory

of the firm, systems theory, sociotechnical systems

theory, group behaviour, action research and

appreciative inquiry, human development, individual

learning theories, organisational change theory and

organisational development theory.

To make the picture even more complex, each of

these influences brings with it a range of different

approaches to the same knowledge area. For

instance, the literature on individual learning within

organisations runs through different streams of

educational, psychological, and organisational

behaviour research (Cowan, 1995). Organisational

learning itself has been studied from different

perspectives including: organisational sciences,

sociological, economics, organisational change, and

development research (Antal, Lenhardt and

Rosenbrock, 2001). Garvin (2000) claims that

despite the popularity of the organisational learning

approach, the field lacks a shared definition and

coherent framework for action, and thus it is of

limited relevance to the practical-minded manager.

There is a clear need to work on the seminal work of

the founders and to integrate theory and practice.

3 ORGANISATIONAL LEARNING

AND ORGANISATIONAL

THEORY

Rami Shani and Peter Docherty (2003) call attention

to the increased popularity of organisational learning

and state that it has shifted to the centre stage of

organisational theory. Authors such as C. Prange

(1999) and the works of Shani and Stjernberg (1995)

suggest and illustrate this move.

An increasing number of organisational theorists

and executives are predisposed to understand and

adopt the learning organisation concept. Some view

organisational learning as a comprehensive approach

that provides a window of opportunity for

assimilating advanced managerial approaches.

However, not all efforts materialise into positive

results. A follow-up study of US organisations

(Moingeon and Edmondson, 1996) that attempted to

assimilate new managerial approaches revealed

some failures among those that did not have the

foresight to construct a suitable mechanism for

organisational learning that incorporated processes,

tools, and work patterns. Shani and Docherty (2003)

refer also that the published literature does not

provide sufficient knowledge regarding

implementation and they state the examples of

Popper and Lipshitz (1998), Raelin (2000), Stebbins

and Shani (2002) and of Ulirich, Jick and Von

Glinow (1993).

Planning makes learning more conscious, better

focuses effort, and increases measures of

accountability, as long as learning does not become

an end in itself with only loose coupling to the work

processes. Planning allows people to nurture

learning strategically and to take advantage of a

wider range of learning strategies that might

otherwise be overlooked. Marsick and Watkins

(1997) indicate several difficulties that may hinder

informal learning, namely:

• organisations do not always let people follow

their natural inclinations to learn in different

ways

• people differ in their capacity to seek needed

information and skills

• there is a disagreement as to what learning to

learn means and therefore as to how to help

people to better learn how to learn

• the topic of learning might require the

assistance of outside experts

• and organisations may not provide clear

guidance regarding what people must know

and how this will assist them in their career

paths

Since learning demands constant and ongoing

questioning and inquiry into current and future

practices, it can be viewed as a continuous

disturbance of existing routines that were developed

for the purpose of stability, predictability and

efficiency.

Faced with the decision to focus on learning,

many managers continue to view the energy, time

and effort spent on learning as wasteful and

unproductive (Garvin, 2000; Schein, 2002).

The situation is further complicated for managers

by the disturbing paradoxes relating to learning,

such as the relations between learning, knowledge

and action. The development situation requires

reflection, experimentation, new alternatives, and

tolerance to risk and uncertainty. Learning requires

balancing routine and reflection. The inherent

ORGANISATIONAL LEARNING – FOUNDATIONAL ROOTS FOR DESIGN FOR COMPLEXITY

87

challenge fosters the need for managers and

practitioners to have access to, and develop basic

understanding of, the ideas and theory behind the

learning organisation mechanisms, including

understanding of their origins and development.

As has already been mentioned, despite the

energy, time, and money that companies spend on

attempts to transform organisations through a variety

of change programmes, the reality is that few

succeed in sustaining the reinventing process (Beer,

2001).

4 ORGANISATIONAL LEARNING

ACCORDING TO SOME KEY

AUTHORS

It is interesting to observe the different ways in

which organisational learning has been described by

leading authors of the field. Shani and Docherty

(2003) collected the following citations as

descriptions of organisational learning or of learning

organisations:

• «... is a process in which members of an

organisation detect error or anomaly and correct

it by restructuring the organisational theory of

action, embedding the results of their inquiry in

organisational maps and images.» (Argyris and

Schön, 1978)

• «...includes both the processes by which

organisations adjust themselves defensively to

reality and the processes by which knowledge is

used offensively to improve the fits between

organisations and environments.» (Hedberg,

1981)

• «... organisations where people continually

expand their capacity to create the results they

truly desire, where new and expansive patterns

of thinking are nurtured, where collective

aspirations are set free, and where people are

continually learning how to learn together.»

(Senge, 1990)

• «...the intentional use of learning processes at

the individual, group and system level to

continuously transform the organisation in a

direction that is increasingly satisfying to its

stakeholders.» (Dixon, 1999)

• «... is an organisation that is skilled at creating,

acquiring, interpreting, transferring, and

retaining knowledge.» (Garvin, 2000)

• «... is a process of inquiry (often in response to

errors or anomalies) through which members of

an organisation develop shared values and

knowledge based on past experiences of

themselves and others.» (Friedman, Lipshitz,

and Overmeer, 2001)

5 THE DESIGN OF LEARNING

MECHANISMS AND

ORGANISATIONAL

COMPETITIVENESS

Organisational learning needs further theoretical

development able to direct and inform organisational

practices and action. Organisational development

itself is the key answer to competitiveness

improvement within the challenging context of the

knowledge economy.

«The literature on learning in the context of

work, at the individual, team, and organisational

levels, is vast. Yet, despite the fact that many

organisations and researchers jumped on the

organisational learning bandwagon, the field lacks a

coherent framework and practical models for

action.» (Shani and Docherty, 2003).

These authors claim that the relation between

individual and collective learning is a ‘chicken and

egg’ question, and that knowledge is created in the

ongoing joint work commitments and dialogues in,

for example, teams.

These authors take a design perspective on

learning and sustainability and state that

organisations make choices about the design and

implementation of specific learning mechanisms that

fit their goals, culture and business context. They

view ‘learning mechanisms’ as: formalised

strategies, polices, structures, processes,

management systems, ICT systems, methods, tools,

routines, and the design of physical or virtual

workspaces that are created for the purpose of

promoting and facilitating ongoing learning in the

organisation. They continue to clarify that learning

mechanisms may concern formal and informal

learning at an individual, team, and organisational

level.

ICEIS 2004 - INFORMATION SYSTEMS ANALYSIS AND SPECIFICATION

88

Shani and Docherty (2003) also state that they

view the learning mechanism for organisational

learning as a formal configuration – structures,

processes, procedures, rules, tools, methods and

physical configurations – created within the firm for

the purpose of developing, enhancing, and

sustaining performance and learning. Just as there

are many types of organisational designs, there are

also various ways to design and manage

organisational learning mechanisms. The design of a

specific configuration is viewed as a rational choice

among alternatives based on learning design

requirements and learning design dimensions.

Achieving and maintaining competitiveness is a

powerful incentive to improve organisational

learning processes, as long as there is a visible link

between the two efforts. Many organisations miss to

see and to work on this link.

Shani and Docherty (2003) claim that «mastering

the art of learning is not a ‘quick fix’». Their

contention is that one of the main reasons for the

failure is that most companies do not manage to

develop and nurture learning mechanisms that allow

them to challenge the basic assumptions about the

key/core business processes and as a result are not

able to alter their mental models and actions. They

call attention to new and increasing learning needs

and give the example of manufacturing companies

that reported in 2001 that they had 80 percent of the

personnel they will have in 2010 but only 20 percent

of the technology, implying that there will be a

strong pressure to constantly adapt to the new

technology. They also stress the fact that the

opportunity to learn is not received by many workers

as an offer of a generous fringe benefit, but rather as

the threat of a ‘last straw that breaks the worker’s

back ‘, meaning that those who will not be

able/willing to learn would have to leave the

company.

The rationale for learning by Shani and Docherty

(2003) is that sustained competitiveness at the

company level requires competence or capabilities

‘on the cutting edge’, which, in turn, requires

continuous learning. They call attention to the recent

developments in business and working life that have

been characterised by the shift from the industrial to

the finance economy, by rapid advances in ICT with

new technology generations every few years,

marked deregulation, and the introduction of

management models and methods to ‘heighten

efficiency and effectiveness’, such as lean

production, time-based management, business

process reengineering, outsourcing, downsizing, and

contingent labour. For companies the goals have

been rationalisation and increased flexibility. For

personnel the consequences have often been

increased work intensity, worse working

environments, and decreased personal security in

terms of employment as has been stressed in the

work of Wickham (2000). The organisational

learning approach may bring together loose ends

within a company’s strategy, through the alignment

of the potentially conflicting interests of key

stakeholders.

A critical issue is that it is relatively easy to

develop a neat theoretical approach to organisational

learning. What is indeed difficult is to live through

that theory in daily organisational life as the

complexity cannot be hidden away as if it were

external to our straightforward model. Thus the need

to dive deep into the waters of other origins of the

field in order to bring some depth and breath to the

organisational learning field. These are the aims of

the next sections.

6 ORGANISATIONAL LEARNING

AND SOCIOTECHNICAL

SYSTEMS

Many of the key issues as well of methodologies

developed within the conceptual framework of

sociotechnical systems, forty years ago, are still

valid to current organisational learning approaches.

However, the links are not always visible or

accounted for.

The origins of sociotechnical systems date from

the period after the second World War. The work of

two social scientists, Fred Emery and Eric Trist,

pioneered the movement toward experimentation

with alternative work redesigns, different forms of

employee involvement, varied degrees of autonomy

and responsibility in work teams, participative

management orientations, and the development of

learning systems, all with deep concerns regarding

economic performance (Emery and Trist, 1969, cited

in Shani and Docherty, 2003).

Based at the Tavistok Institute in London, in the

early 1950s they introduced a method known as

sociotechnical systems design to British industry.

Their work is a landmark in the field of

organisational design, change, and development, as

it is represented the first attempt to introduce

flexible learning forms of organisation into the

world of work.

Eric Trist’s study focused the work organisation

of the coal-mining British industry which had been

nationalised straight after the war (Obholzer and

Roberts, 1994). Through this study it was discovered

that groups of workers supposedly doing similar jobs

in separate coal mines in fact organised themselves

very differently, and that this had significant effects

ORGANISATIONAL LEARNING – FOUNDATIONAL ROOTS FOR DESIGN FOR COMPLEXITY

89

on levels of productivity. This led to the concept of

the self-regulating work group, and to the idea that

differences in group organisation reflect unconscious

motives, which also affect the subjective experience

of the work. It was through this project that the

‘socio-technical systems’ came to be defined as an

appropriate field of study (Thrist et al, 1963, cited in

Obholzer and Roberts, 1994 ).

Organisations as sociotechnical systems can be

understood as the product of the interaction between

a work task, its appropriate techniques and

technology, and the social organisation of the

workers pursuing it. While originating from research

in industry, this approach has subsequently been

applied to the study of a wide range of organisations.

In particular, Isabel Menzies’ study, «Social systems

as a defence against anxiety» (1960, cited in

Obholzer and Roberts, 1994), to identify the causes

of high drop-out rate from nurse training was an

early example of bringing the Tavistock Institute of

Human Relations (TIHR) sociotechnical model to

bear on an institution where the technical system is

largely human.

7 ORGANISATIONAL LEARNING

AND SYSTEMS THEORY

Systems theory is an area which has had a profound

foundational influence in organisational learning

even if not always visible, recognisable or

recognised.

Systems theory was also another avenue for

research at the Tavistock Institute of Human

Relations (TIHR) in the post-war era (Obholzer and

Roberts, 1994), as it was one of the imports from the

social sciences that underpinned socio-psychological

thinking. The particular application of open systems

theory to the work of TIHR was substantially the

contribution of A. K. Rice, later working with Eric

Miller.

In essence, the open systems view sees an

institution as having boundaries across which inputs

are drawn in, processed in accordance with a

primary task, and then passed out as outputs. While

this may sound like a model best suited to

understanding manufacturing processes, Miller and

Rice (1967, cited in Obholzer and Roberts, 1994)

applied it far more widely. They traced many of the

difficulties faced by work groups to their problems

in defining their primary task and in managing their

boundaries.

TIHR researchers did not go in as experts who

already knew what their clients must do to improve

things: they went to study whatever they would find.

The study was undertaken jointly with the clients,

and, to a large extent, by them. TIHR staff then

sought to contribute a way of construing their

observations and experiences, which they believed

would point to potentially helpful changes. Once

introduced, the effects of the changes would

themselves become the subject of further study,

leading to further change. The role of the TIHR staff

member was designated as ‘participant observer’,

and the whole style of working was known as

‘action research’.

Within systems theory the notion of autopioesis

has a critical role. Autopoiesis is a term from

biology which was adapted and adopted by

Maturana and Varela to describe the ‘organisation of

the living’ (Maturana and Varela, 1980, cited in

Winograd and Flores, 1986). Maturana was a

neurophysiologist who greatly developed the

biological aspects of cognition. He searched for

explanations of the origins of all phenomena of

cognition in terms of the species history, the

phylogeny, and in terms of the individual history,

the ontogeny, of living systems. According to

Maturana, an autopoietic system holds constant its

organisation and defines its boundaries through the

continuous production of its components.

Winograd and Flores (1986) while aiming at

studying the design of computer technology, use

Maturana’s theories as well as those from different

philosophers in order to develop an ‘understanding

of computers and cognition’. They explain their

rationale this way:

«All new technologies develop within a

background of a tacit understanding of human nature

and human work. The use of technology in turn

leads to fundamental changes in what we do, and

ultimately in what it is to be human. We encounter

the deep questions of design when we recognise that

in designing tools we are designing ways of being.

By confronting these questions directly, we can

develop a new background for understanding

computer technology – one that can lead to

important advances in the design and use of

computer systems.» (1986)

As the work of these authors is, on one way,

philosophical and, on another way, directed to the

study of computing technology, it may seem

detached from the domain of organisational learning

as a knowledge field. However, if we take a broader

and deeper view of the issues which are at stake in

the study of organisational learning as a dynamic,

continuous and complex process, then it is critical

that the insights from these apparently far away

areas are translated and incorporated into the

organisational learning discipline.

Herbert Simon (1991), who was working also

within the field of computing technology and

artificial intelligence, has dedicated his work to a

ICEIS 2004 - INFORMATION SYSTEMS ANALYSIS AND SPECIFICATION

90

very broad range of subjects which included the

development of complex systems theory. In fact, he

started his research considering the issues of

organisational endeavours:

«... administration is not unlike play-acting. The

task of the good actor is to know and play his role,

although different roles may differ greatly in

content. The effectiveness of the performance will

depend on the effectiveness of the play and the

effectiveness with which it is played. The

effectiveness of the administrative process will vary

with the effectiveness of the organisation and the

effectiveness with which its members play their

parts.» (Simon, 1991)

Simon calls attention to the fact that «complexity

is more and more acknowledged to be a key

characteristic of the world we live in and of the

systems that cohabit our world.» (1991). He

ascertains that though science has been focusing on

complex systems through the study of astronomy,

economics, biology or psychology, what is relatively

new today is the study of complexity in its own

right. As complexity, or systems science, is too

general a subject to have much content, then

particular classes of complex systems become the

focus of attention, and that is how H. Simon explains

the emergence of the study of chaos or hierarchical

systems.

Simon (1991) defines complex systems as made

up of a large number of parts that have many

interactions, and states that formal organisations

have a clearly visible parts-within-parts structure,

thus implying that they are social systems. Other

examples of social systems that he mentions are

families, villages and tribes. He refers to biological

and to physical systems and also to «one very

important class of systems: systems of human

symbolic production», citing the example of a book

or a musical work. Simon’s work is itself highly

complex though here we are merely referring to

simple descriptions and examples with the intention

of illustrating the basic links between organisational

learning and systems theory.

8 ORGANISATIONAL LEARNING,

APPRECIATIVE INQUIRY AND

SOFT SYSTEMS THEORY

Still within the broad area of systems theory, the

development of human and social related approaches

greatly resembles one of the core aspects of the

organisational learning field that it deals with

people. The term ‘people’ represents not only single

autonomous individuals or collections of

independent autonomous individuals, but persons

who are part of social practices and of social

structures. The etymology of the word ‘person’

means individuals in relationship. These ‘individuals

in relationship’ are simultaneously determined be

the practices and structures to which they belong, as

well as they themselves partly determine those

practices and structures.

Peter Checkland is a theorist who has worked in

systems theory for over thirty years and gives the

following account (1999):

«Although history of thought reveals a number

of holistic thinkers – Aristotle, Marx, Husserl among

them – it was only in the 1950s that any version of

holistic thinking became institutionalised. The kind

of holistic thinking that came to the fore, and was

the concern of a newly created organisation, was that

which makes explicit use of the concept of ‘system’,

and today it is ‘systems thinking’ in its various

forms which would be taken to be the very paradigm

of thinking holistically.» (1999)

The same author (1994) refers to the importance

of two inquiring systems developed since the 1960s:

soft system’s methodology and Vickers’ concept of

appreciative inquiry (1965). He claims that these are

highly relevant to the twenty first century, as both

assume that organisations are more than rational

goal-seeking machines, and address the relationship-

maintaining and Gemeischaft (translated as

Community) aspects of organisations, obscured by

functionalist and goal-seeking models of

organisation and management. Checkland states that

appreciative systems theory and soft systems

methodology enrich rather than replace these

approaches.

Checkland had previously summarised Vickers’

main themes and broad description of appreciate

systems theory (Checkland and Casar, 1986) as:

• A rich concept of day-to-day experienced life

• A separation of judgements about what is the

case, reality judgements, and judgements about

what is humanly good or bad, value judgements

• An insistence on relationship maintaining as a

richer concept of human action than the popular

but poverty-stricken notion of goal seeking

• A notion that the cycle of judgements and

actions is organised as a system

Checkland also explains that soft systems

methodology was not an attempt to operationalise

the concept of an appreciative system (1994).

Rather, it was after soft systems methodology had

emerged from an action research programme at

Lancaster University that it was discovered that its

process mapped to a remarkable degree the ideas

that Vickers had been developing in his books and

articles (Checkland, 1981, cited in 1994).

ORGANISATIONAL LEARNING – FOUNDATIONAL ROOTS FOR DESIGN FOR COMPLEXITY

91

Checkland continues to explain that the

Lancaster programme began by setting out to

explore whether or not, in real-world managerial

rather than technical problem situations, it was

possible to use the approach of systems engineering.

He states that it was found to be too naïve in its

questions to cope with managerial complexity:

‘What is the system? What are its objectives?’

Checkland continues (1994): «We can now say that

managerial complexity was always characterised by

conflicting appreciative settings and norms.».

An interesting parallelism between systems

theory and organisational learning theory is that soft

systems methodology was characterised as a

learning system (Checkland and Scholes, 1990, cited

in 1994): «... a learning system in which the

appreciative settings of people in a problem situation

– and the standards according to which they make

judgements – are teased and debated.» And

Checkland continues to clarify: «The influence of

Vickers on those who developed soft systems

methodology means that the action to improve the

problem situation is always thought about in terms

of managing relationships – of which the simple

case of seeking a defined goal is the occasional

special case.»

The need for organisational learning, as a

practice, to incorporate the decades old lessons of

appreciative inquiry and soft systems theory is not

so much a mentalistic or intellectual exercise. It is

more a question of experiencing organisational

learning through the eyes of new approaches – new

in terms of daily and standard organisational

practices. It is related to how the actual reality is

interpreted and then reinterpreted through new

learning experiences.

CONCLUSION

The current paper gives a general account of several

origins of the organisational learning field and it

focus on key foundational issues which are relevant

to the future development of the field.

Organisational learning design, through a special

attention to the processes, structures, strategies,

methods and tools which support and continuously

maintain learning, is highlighted as an essential

element on any project that has an intention to apply

the organisational learning approaches to a real life

situation.

Often continuous improvement methodologies as

well as organisational learning projects fail to grasp

the benefits subjacent to these conceptual tools

because they are not able to understand three central

issues.

One is that any organisational restructuring

process must take into account the organisation as a

whole. In order to do this, it is necessary to

understand the concept of holism, and systems

theory is one way of enabling this perspective to be

applied.

Secondly, the issue of social and human

characteristics which permeates every aspect of

organisational life must be considered and

understood in a way that does not oversimplify

reality. The early influence of the development of

the appreciative inquiry is an example – there could

be several other - of how these issues may be

tackled.

Thirdly, the importance of complexity which is

inherently and directly related to both previous

issues. Humans are highly complex in themselves

and organisations are obvious examples of complex

systems. Complexity is particularly critical to

practice and applied approaches such as is the case

of the organisational learning knowledge area.

The central message to be delivered is the need

for organisational learning to take a fuller depth and

breath approach to the diverse and interdisciplinary

influences which characterise its core identity as a

management and organisational theory discipline.

REFERENCES

Abrahamson, E., 1996. Management fashion. Academy of

Management Review, 21(1), 254-85.

Abrahamson, E., 1999. Lifecycles, triggers, and collective

learning processes. Administ. Science Quarterly,

44(4), 708-40.

Antal, A., Lenhardt, U. & Rosenbrock, R., 2001. Barriers

to organisational learning. In A. Antal, M. Dierkes, J.

Child and I. Nonaka (eds), Handbook of

Organisational Learning and Knowledge. New York:

Oxford University Press.

Argyris, C. & Schön, D., 1978. Organisational Learning:

a Theory of Action Perspective. Reading, MA:

Addison-Wesley.

Beer, M., 2000. Research that will break the code of

change: The role of useful normal science and usable

action science. In M. Beer and N. Nohria (eds),

Breaking the Code of Change. Boston: Harvard

Business School Press.

Beer, M., 2001. How to develop an organisation capable

of sustained high performance. Organ. Dynamics,

298(4), 233-47.

Checkland, P. & Casar, A., 1986. Vicker’s concept of an

appreciative system. Journal of Applied Systems

Analysis, 13, 3-17.

Checkland, P. & Scholes, 1990. Soft systems methodology

in action. Chichester: Wiley.

ICEIS 2004 - INFORMATION SYSTEMS ANALYSIS AND SPECIFICATION

92

Checkland, P., 1993. Systems Thinking, Systems Practice.

Sussex, UK: Wiley.

Checkland, P., 1994. Systems Thinking and Management

Thinking. American Behavioural Scientist. 38 (1).

USA: Sage.

Checkland, P., 1999. Soft Systems Methodology: a 30-year

retrospective. Sussex, UK: Wiley.

Cowan, D., 1995. Rhythms of learning: Patterns that

bridge individuals and organisations. Journal of

Management Inquiry, 4(3), 222-46.

Dixon, N., 1999. The Organisational Learning Cycle.

Hampshire, England: Power Publishing.

Emery, F. & Trist, E., 1969. Sociotechnical systems. In F.

Emery (ed), System Thinking. Handsworth: Penguin.

Friedman, V., Lipshitz, R. & Overmeer, W., 2001.

Creating conditions for organisational learning. In A.

Antal, M. Dierkes, J. Child, and I. Nonaka (eds),

Handbook of Organisational Learning and

Knowledge. New York: Oxford University Press.

Garvin, D., 2000. Learning in Action. Boston, MA:

Harvard Business School Press.

Gibson, J. & Tesone, D., 2001. Management fads:

Emergence, evolution, and implications for managers.

Academy of Management Executive, 15(4), 122-33.

Hedberg, B., 1981. How organisations learn and unlearn.

In P. Nystrom and W. Starbuck (eds), Handbook of

Organisational Design. New York: Oxford University

Press.

Kearmally, S., 1999. When economics means business.

London: Financial Times Management.

Lillrank, P., Shani, A. & Lindberg, P., 2001. Continuous

improvement: Exploring alternative organisational

designs. Total Quality Management, 12(1), 41-55.

Marquardt, M & Reynolds, A., 1996. Learning across

borders. World Executive Digest, May, 22-5.

Marsick, V. & Watkins, K., 1997. Lessons form informal

and incidental learning. In J. Burgoyne and M.

Reynolds (eds), Management Learning: Integrating

Perspectives in Theory and Practice. London: Sage.

Maturana, H. & Varela, F., 1980. Autopoiesis and

Cognition: The realisation of the Living. Dordrecht:

Reidel.

Menzies, I., 1960. Social systems as a defence against

anxiety. In E. Trist and H. Murray (eds) 1990. The

Social Engagement of Social Science, Vol. 1: The

Socio-Psychological Perspective, London: Free

Association Books.

Miller, E. & Rice, A., 1967. Systems of Organisation: The

Control task and Sentient Boundaries, London:

Tavistock Publications.

Moingeon, B. and Edmondson, A., 1996. Organisational

Learning and Competitive Advantage. Thousand Oaks,

CA: Sage

Obholzer A. & Roberts, V., 1994. The Unconscious at

Work. London: Routledge.

Popper, M. & Lipshitz, R., 1998. Organisational learning

mechanisms: a structural and cultural approach to

organisational learning. Journal of Applied

Behavioural Science, 34(2), 161-79.

Prange, C., 1999. Organisational learning - desperately

seeking theory? In J. Burgoyne and L. Araujo (eds),

Organisational Learning and the Learning

Organisation: Developments in Theory and Practice.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Pursuer, R. & Cabana, S., 1998. The Self-Managing

Organisation: How Leading Companies are

Transforming the Work of Teams for Real Impact.

New York: The Free Press.

Raelin, J., 2000. Work-Based Learning. New Jersey:

Prentice Hall.

Rami, A. & Docherty, P., 2003. Learning by Design.

Oxford UK: Blackwell Publishing.

Schein, E., 2002. The anxiety of learning. Harvard

Business Review, 80(3), 100-6.

Senge, P., 1990. The Fifth Discipline. New York:

Doubleday.

Shani, A. & Stjernberg, T., 1995. The integration of

change in organisations: Alternative learning and

transformation mechanisms. In W. Pasmore and R.

Woodman (eds), Research in Organisational Change

and Development, vol. 8. Greenwich, CT:JAI Press,

77-121.

Simon, H., 1991. The Sciences of the Artificial. USA: MIT

Press.

Stebbins, M. & Shani, A., 2002. Eclectic design for

change. In P. Docherty, J. Forslin and A. Shani (eds),

Creating Sustainable Work Systems: Emerging

Perspectives and Practice. London: Routledge.

Thrist, E., Higgin, G, Murray, H. & Ollock, A., 1963.

Organisational Choice. London: Tavistock

Publications.

Ulirich, D., Jick, T. & Von Glinow, M., 1993. High

impact learning: building and diffusing learning

capability. Organisational Dynamics, 22(2), 52-66.

Vickers, G., 1965. The art of judgement. London:

Chapman & Hall.

Wickham, J., 2000. Understanding technical and

organisational chance. In Towards a Learning Society:

Innovation and Competence Building with Social

Cohesion for Europe. Dublin: Employment Research

Centre, Dept of Sociology, Trinity College Dublin.

Winograd, T. & Flores, F., 1986. Understanding

Computers and Cognition – a new foundation for

design. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

ORGANISATIONAL LEARNING – FOUNDATIONAL ROOTS FOR DESIGN FOR COMPLEXITY

93