Knowledge Sharing in Negotiation Process

Coordination

Melise Paula

1

, Jonice Oliveira

1

, Jano Moreira de Souza

1,2

1

COPPE/UFRJ - Computer Science Department, Graduate School of Engineering / Federal

University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

2

DCC-IM/UFRJ - Computer Science Department, Mathematics Institute, Federal University of

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Abstract. In negotiations, independent of the context in which these are being

applied, the goal is reaching an agreement, and every agreement comprises a

decision making result. The negotiator‘s expertise can determine the success of

a project. Of great importance is the greatest possible amount of information on

the negotiation, so as to secure competitive data which can sway the negotiation

and identify the potential benefits for the other party. Furthermore, negotiation

environment information and individual knowledge about both parties as well

as previous experience in negotiations can be useful in new negotiations. This

scenario requires a management model which should be able to capture and

manage this knowledge, disseminating it to the negotiators, and improving the

results from negotiations. The aim of this work is to propose an environment to

support cooperative negotiation processes, managing the knowledge acquired in

each negotiation, providing necessary knowledge during the process and

enabling interaction between negotiators

.

1 Introduction

The current highly dynamic and competitive economy defines a scenario in which it

has become indispensable to sign agreements, partnerships and alliances, thereby

bringing forth the need for constant negotiation.

Traditionally, two types of negotiation exist: competitive and cooperative 4,9,15.

Competitive negotiation (also known as Zero-sum in the context of the Game Theory

and Operational Research) is classified as Win/Lose. The negotiator with a Win/Lose

posture chooses the competition and the short time. Thus, the fulfillment of the wishes

of one party may be directly detrimental to the fulfillment of the wishes of another

party. Cooperative negotiation (also known as collaborative negotiation) is classified

as Win/Win. It is a cooperative process in which involved parties find alternatives for

common earnings, that is, which cater to the interests of all the parties 1,4,15.

In cooperative negotiations, it is essential to stimulate the communication and

cooperation among users so as to facilitate information exchange and negotiation

process development. Thus, technology becomes extremely important to meet the

need for processing and managing data and information related to each situation, so

the parties involved can make the right decision according to their objectives.

Paula M., Oliveira J. and Moreira de Souza J. (2004).

Knowledge Sharing in Negotiation Process Coordination.

In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Computer Supported Activity Coordination, pages 126-135

DOI: 10.5220/0002683201260135

Copyright

c

SciTePress

Therefore, it is necessary to develop applications providing support to the negotiation

process by promoting the best information management through appropriate resources

such as the Internet.

The negotiator often needs to be in contact, and to interact, with people belonging

to diverse, and sometimes conflicting organizational cultures, thereby diversifying his

or her form of behavior, and allowing the process to flow in a common direction

between the parties, until agreement is reached.

Another decisive factor present at the negotiation table is the negotiator’s own

experience, and his or her level of knowledge regarding the negotiator’s role. In the

context of the negotiation, the load of information that the negotiator needs to acquire

about the organization and about the groups of people with whom he or she will have

to interact during the process should also be taken into account.

In order to keep the flow of acquired knowledge constant, and to add value to each

new negotiation, individual knowledge (of each professional) and process knowledge

need to be within the organization management, in this way building up competitive

advantage.

Knowledge management (KM) emerges in this context. KM can be considered an

array of processes which has supported the creation, dissemination and use of

knowledge to fully reach objectives. Information Technology contributes to KM 2,8,

thus providing a computational environment for KM support which can lead

improvements to the results achieved in the negotiations.

The purpose of this work is to present an environment for supporting cooperative

negotiations, managing the knowledge acquired in each negotiation, bringing forth

new knowledge during the process as well as closer interaction between the parties

involved, thereby allowing for exchanging experiences and disseminating the

acquired knowledge, and optimizing the results secured by all the parties involved in

the negotiation. It is important to highlight that it is not within the scope of this work

to present a detailed study about Negotiation and Knowledge Management.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 discusses a number

of theoretical aspects of negotiations. As the objective of this research is proposing a

KM environment to facilitate negotiation, some formal aspects of the KM applied to

negotiation will be presented in section 3. Section 4 presents our proposal, an

environment for supporting a collaborative negotiation process through KM. Future

works and the conclusion are shown in section 5.

2 Negotiation: theoretical aspects

According to Lomuscio et. al. 14, negotiation can be defined as: “Process by which a

group of agents communicates with one another to try and come to a mutually-

acceptable agreement on some matter”. In this definition, the accent falls on words

such as ‘agent’, ‘communicate’, and ‘mutually acceptable’. The parties taking part in

the negotiation process are not necessarily people, but can be any type of actors, such

as software agents.

E-Negotiation appears in this context. According to Kersten 13, E-negotiations are

negotiation processes fully or partially conducted with the use of electronic media

(EM), which use digital channels to transport data. EM may support simple

127

communication acts between the participants (e.g., e-mail, chat) or provide tools

allowing for complex, multimedia interactions (e.g., e-markets, electronic tables).

This work is based on Kerstin’s definition about E-negotiation.

The consideration of a medium as a space (physical or virtual) wherein the

negotiation is being conducted as well as the agents who interact in this space, allows

for distinguishing between three categories of information systems used in e-

negotiations: Negotiation support tools, such as DSS and NSS, assist a decision maker

with communication or decision tasks in a negotiation process; Negotiation software

agents (NSA) replace human negotiators in all their decision-making, communication

and other negotiating activities; E-negotiation media are information systems

comprising electronic channels that process and transport data among the participants

involved in a negotiation and provide a platform where transactions are coordinated

through agent interaction 13,11.

These actors communicate according to a negotiation protocol and act as according

to a strategy. The protocol determines the flow of messages between the negotiating

parties and acts as the rules by which the negotiating parties must abide by if they are

to interact. The protocol is public and open. The strategy, on the other hand, is the

way in which a given party acts within those rules, in an effort to get the best outcome

of the negotiation. The strategy of each participant is, therefore, private 3,7.

As with every process, a negotiation can be divided in phases. In Kersten and

Noronha 12, the authors suggest three phases of the negotiation: pre-negotiation,

conduct of negotiation and post-settlement.

In the pre-negotiation phase, the objective is the understanding of the negotiation

problem. This phase involves the analysis of the situation, problem, opponent, issues,

alternatives, preference, reservation levels and strategy. Moreover, in this phase,

negotiators plan the agenda of the negotiations and develop their BATNA.

BATNA is the acronym for "Best Alternative To a Negotiated Agreement",

created by Roger Fisher and Willian Ury 7. The BATNA can be identified in any

negotiation situation by the question, “What will we do if this negotiation is not

successful?” Vigorous exploration of the options that might exist outside the current

negotiation can tip the balance of power in a negotiation. However, attractive

alternatives may not always be immediately obvious. Sometimes it will take time to

identify what these alternatives are and more time again to make them attractive. This

is, almost always, time well invested, as having a strong alternative improves the

ability to negotiate a good deal in the current negotiation.

In the simplest terms, if the proposed agreement is better than your BATNA, then

you should accept it. If the agreement is not better than your BATNA, then you

should reopen negotiations. If you cannot improve the agreement, then you should at

least consider withdrawing from the negotiations and pursuing your alternative

(though the costs of doing that must be considered as well). One of the main reasons

for entering into a negotiation is to achieve better results than would be possible

without negotiating 23.

The BATNA’s advantages are the greater range of alternative courses of action

and the ability to walk away from an unsatisfactory negotiation. More details on the

BATNA can be found in 7,16,20.

The second phase of the negotiation, Conduct of negotiation, involves exchanges

of messages, offers and counter-offers based on different strategies and the kinds of

negotiation. The post-settlement analysis phase involves only the evaluation of the

128

negotiation outcomes generated, and, afterwards, the negotiation activity. These

outcomes include the information about the compromise and the negotiators’

satisfaction.

Those new technologies present great possibilities for information exchange and

decision-making support of the parties involved in the negotiation process. The

challenge of this work is to use the technology to capture, store and make available

the knowledge about the negotiation through a management model and to define one

cooperative negotiation protocol ordering the negotiations through this model.

3 Knowledge Management Applied to Negotiation

According to Snowden 22, Knowledge Management can be defined as intellectual

asset identification, optimization and management , in the form of explicit knowledge

built into documents, or tacit knowledge belonging to the individuals or communities.

Created knowledge management in a negotiation process facilitates future

negotiations and provides inexperienced negotiators with learning based on

community knowledge. There is knowledge creation in each one of the stages

described by Kersten et. al. 12 and the negotiation process can be mapped on the

knowledge creation process proposed by Nonaka and Takeuchi 18.

In the pre-negotiation phase, new knowledge is created by data search and analysis

and information raising. The negotiator (or group of negotiators) needs to study more

about the domain in which he/she is acting, it sometimes being necessary to access

information in reports, books, papers or other sources of information. At this phase,

there is intense data collection, analysis and manipulation, and this data can be

classified and used in a new context, similar to the Combination process. After the

Combination process, the analyzed data imparts a new meaning to the negotiator,

similar to the process of Internalization, in which the explicit knowledge is acquired

and can be transformed into tacit knowledge. Eventually, explicit knowledge is

regarded as insufficient and other allied negotiators and experts about the domain are

consulted. New knowledge can be created from this interaction, akin to the

Socialization process.

One of the results of the pre-negotiation phase is the BATNA, which can be seen

as knowledge externalization. Each negotiator bears experiences, sensations and own

negotiation characteristics which are, somehow, documented on the planning and

elaborating of this document type. In other words, each BATNA comprises

knowledge externalization of the negotiation process on a domain.

Negotiation conduction is found in the second phase of the negotiation, a strong

interaction between the parties, so that new knowledge about decisive facts can be

acquired. Personal opinions, trends and the opponent’s features, learned through

contact and mutual actions can be cited as decisive factors here. This learning process

is represented by socialization. The post-negotiation phase involves the evaluation

and documentation of the results achieved, this step comprising an Externalization

process.

129

4 Proposed Architecture

The proposal for elaborating a computational environment for knowledge

management in negotiations arose with the aim of following up on the negotiation

process, so as to capture and manage the knowledge regarding this process, rendering

it available and accessible, so that the negotiators can acquire this knowledge and

apply it in the attempt of optimizing the results obtained in the negotiations.

In the design of this work, a number of negotiation tools available for training were

analyzed: Cybersettle 5, Smartsettle 21, Inspire 10, Negoisst 17, WebNS 24 being

possible to identify that some ordinary requirements from Knowledge Management

had not been considered. Hence, the focus of this environment is the management of

knowledge acquired by the parties during a negotiation process, with the major

objective facilitating decision-making, bringing forth new knowledge during the

process as well as closer interaction between the parties involved, thereby allowing

for exchanging experiences and disseminating the acquired knowledge, in addition to

optimizing the results.

The architecture of the proposed environment is distributed in two layers: i) The

Process Layer and ii) The Knowledge Layer. In the process layer, tools were analyzed

for supporting the negotiation process and elaborating a cooperative negotiation

protocol; in the knowledge layer, tools were analyzed for knowledge management. In

the last layer, the adaptation of the environment Epistheme 19 will be analyzed in the

negotiation context. The environment Epistheme was developed by Oliveira et. al. 19

and applied to some research projects. The objective is analyzing what possible

benefits this environment may provide when implemented as a tool for knowledge

management in negotiation.

4.1 Process Layer: Tools for Supporting the Negotiation Process

In the Process layer, a cooperative negotiation protocol is defined, as well as how the

process is structured and modeled on account of the process phases, interaction

among negotiators being facilitated through the use of CSCW’ technologies and

Groupware 6. Some of the benefits reached by the use of this technology, such as ease

of communication, classification of subjects, discussion-group environment, are

viewed as an explanation for the growing interest of the organizations in which they

are adopted.

The modeling of the process was defined by the identification of the steps to be

followed. The first step for a negotiation is the identification by the parties of a

negotiation opportunity through the identification of compatible interests. According

to the application context of the proposed negotiation platform, the users can record

their intention of negotiating and, through this data, the Identification of a

Negotiation’ Opportunity can be made. The challenge in this stage is to allow for the

automatic identification of this compatibility, stimulating and accelerating the

negotiations.

After a negotiation opportunity is identified, the involved users can be interested

in securing more information about the possible negotiation. The first step is

preparing for the negotiation. The support to the activities in the preparation phase

130

can be divided in two levels: user level and decision level. In the user level, every

user will have an exclusive individual access area, in which all the important

information about the negotiation can be stored, such as the BATNA. In the decision

level, the available knowledge can facilitate decision-making when more than one

business opportunities have been found.

After the preparation, one of the users may wish to start the contact. At this point,

the system alters the stage of the negotiation to ´Negotiation in process´. During this

stage, it is essential to stimulate communication and cooperation through users to

facilitate information exchange and negotiation process development.

Electronic mail can be used to enable asynchronous communication among the

users of the system. The available resources in the Instant Messenger tools can be

adapted in order to identify online users and exchange information in real time using

an e-meeting tool (such as Chat). Both tools comprise internal functionalities of this

environment.

The e-meeting tool resource allows for informal communication through this user

channel, which is extremely important for the success of the negotiation process. In

this case, the exchanged messages are not categorized. However, for each e-mail

message, a pattern should be specified to represent user intention.

Moreover, the users involved in a negotiation will have access to a common area,

in which they can include important negotiation information, such as for instance, the

negotiation agenda. The bulletin board will be used to such aim, a CSCW tool

supporting asynchronous communication among users through a free area and shared

by a group, and being able to attach, read, and answer the available messages. The

bulletin board can also be used by those users who need more explicit advertisement

of their information and it presents an alternative, providing the users with a graphic

facility to highlight the advantages of their proposals. Moreover, the risk of losing this

information is reduced.

In a general way, following the agreement, the next step in the negotiations is the

signing of the commitment term or agreement. To facilitate the elaboration of the

term, the electronic form of agreement (EFA) begins to be generated automatically

when the users confirm their interest in the negotiation. Thus, the system is

responsible, for it increases the following information: identification of the involved

users (name, position, Agency) and the description of the subject of negotiation.

However, during the Preparation of negotiation stage, the users must establish

who will have the role of filling out of the topics resolved at the end of the process.

This user is called responsible user for EFA. In the “Negotiation in process” stage,

following the agreement, the users should inform the system that agreement was

reached, and the system should alter the negotiation stage to the ´Pending EFA´ stage.

Thus, the responsible user for EFA should carry out its completion and, when

finished, the form is automatically sent, to all the users involved, for approval. The

negotiation is only completed when all the parties approve the EFA. At this point, the

negotiation state is altered to ´Completed Negotiation´. Pending this to happen, the

negotiation stays in the system under the ´Pending EFA’ stage. That functionality can

be seen as an electronic contract signature, since the negotiation is not completed

before approval by all the involved users, with the agreement recorded in the system.

On the other hand, in case agreement is not possible, the users should complete the

negotiation by informing the system that it has not been possible to secure agreement.

131

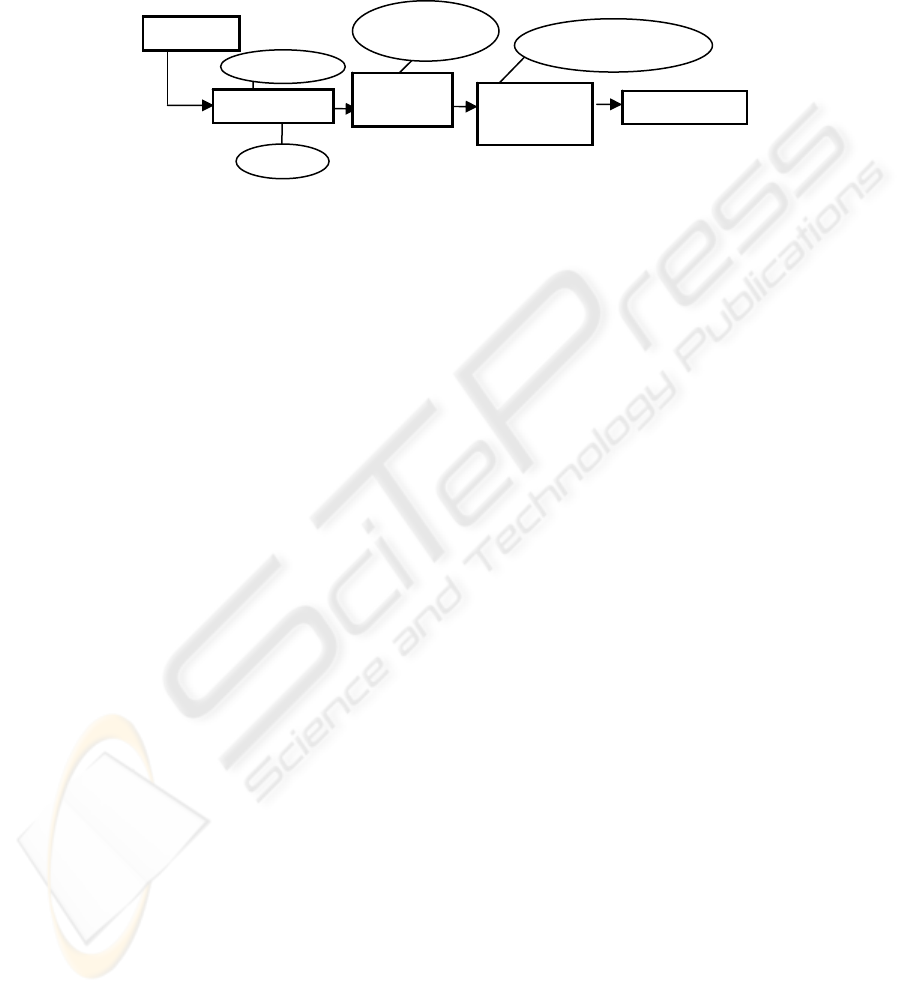

Figure 1 illustrates the negotiation process schema, considering that an agreement

has been reached. The rectangles represent the process stage, the arrows the activities

responsible for the transition of those stages, and the ellipses highlight the important

activities in each state.

Fig 1. Negotiation Process Schema

4.2 Knowledge Level: KM support tools

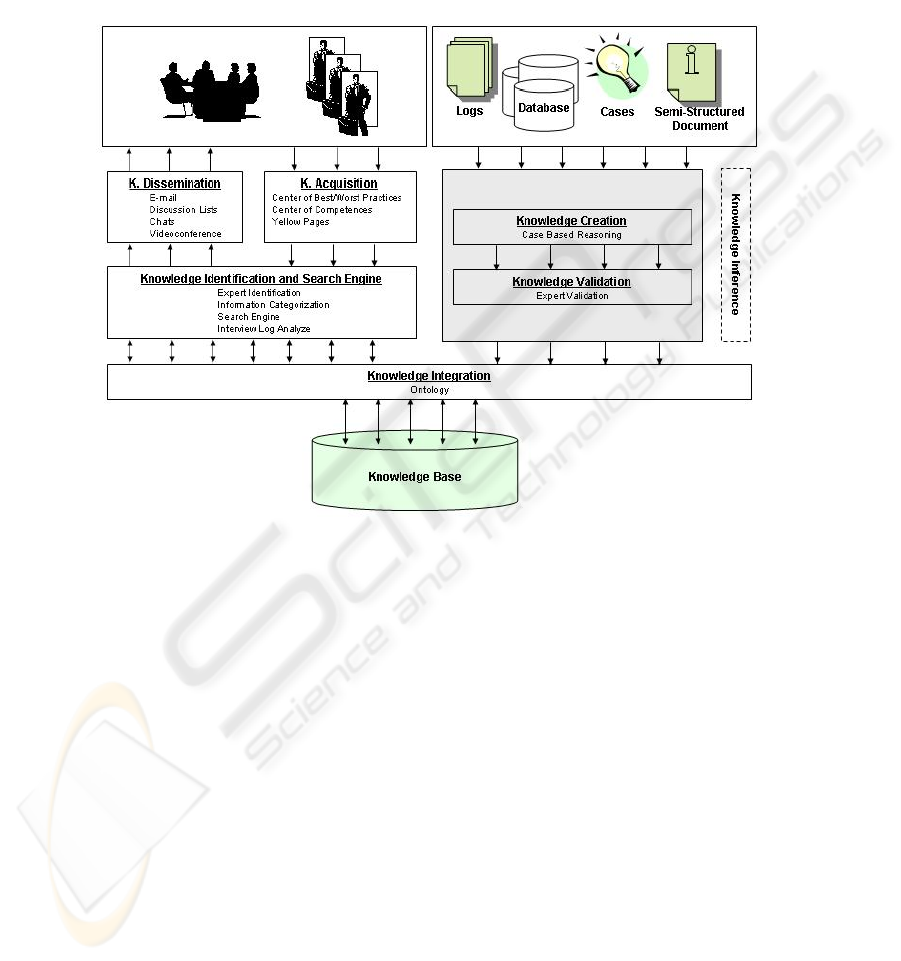

In this case, use is made a computational environment named Epistheme for the

management and selective dissemination of the knowledge in the negotiation process

stages. Epistheme 19 is an environment created to aid Knowledge Management and,

in this task, its function is managing the knowledge obtained during the negotiation

process and providing a learning platform in addition to knowledge sharing on the

organization. To reach the established objective, Epistheme is formed by knowledge

acquisition, identification, integration, validation and creation modules, as seen in

Figure 2.

The Knowledge Acquisition Module has as its purpose the capturing of

knowledge through the interaction of Epistheme with people and its storing in

structured form. To do so, Epistheme bears three sub-modules: Center of Practices,

Center of Competences and Yellow Pages.

In the center of Best Practices and Worst Practices, specialists can render a

successful or an unsuccessful project available, as well as information on its

elaboration, with the modeling of the entire executed process becoming useful for

greater knowledge exchange between negotiators.

Centers of Competences are communities providing a forum for the exchange and

acquisition of tacit knowledge referring to a domain, enabling negotiators to interact

with one another and exchange knowledge.

In this module, the online interviews with specialists in the Center of

Competences are mechanisms used for knowledge extraction, due to their simplicity.

Another form of knowledge acquisition, achieved in an asynchronous manner,

comprises the use of discussion lists, in which each question can be submitted to a

Center of Competences, with one or more specialists from the center answering these.

Knowledge extracted from these activities should later be formalized and inserted in

the knowledge base, a task to be executed by the knowledge identification module.

The Yellow Pages tool is used to facilitate finding data suppliers and internal

customers, as well as to carry through quality control and regularity of the supplied

data.

To confirm

interest

To begin

contact

To fulfill

EFA

Pending

EFA

To approve

EFA

Co

n

c

l

us

i

o

n

In

Process

Pr

ep

arati

o

n

EFA

Agreement

BATNA

To finalize EFA

Identif

y

132

The identification of organizational knowledge starts with the recognition of the

necessary knowledge for the execution of tasks, of those who execute them (the

actors) and of the importance of each task. The Knowledge Identification module is

still comprised of tools for finding relevant information, experts on an issue, and

information categorization.

Automatic knowledge creation is carried out by the “Case-Based Reasoning”

(Knowledge Creation module), capable of identifying the same, or similar, cases

broached in the past, thus generating new conclusions based on already-existing

knowledge. A specialist in the validation module verifies these conclusions.

Data and information can frequently be strongly associated to many areas, even

though they are treated with different names according to the applied domain.

Therefore, it is necessary to identify the data and information correlated in different

areas, this being the responsibility of the integration layer through the use of

ontologies. The Knowledge Integration module is responsible for creating and editing

domain ontology in a collaborative way.

All information or data is distributed automatically to users, considering the kind

of data inserted in the knowledge base and the way it can be useful, meanwhile taking

into account the user’s profile. The Knowledge Dissemination Module uses tools such

as e-mail, discussion forums, chats, audio and videoconference, and in the future, we

will add a recommendation system to this module.

Fig 2. Epistheme Architecture

133

5 Conclusion and Future Works

Negotiations have to be fast, and in a cooperative manner, no matter where the

negotiators are located, in the current, geographically-distributed organizations

operating in a dynamic market, so as to account for group decisions, with the

participation of all parties.

The use of CSCW and KM tools has been analyzed in the proposed environment.

Thus, we could identify tools and functions associated to those areas which can be

appropriately adapted to each step of the negotiation process.

The CSCW tools used in the system stimulate cooperation and facilitate

communication among its users. The following-up of negotiation stimulates and

speeds up the process, and facilitates the decision-making process. The automatic

identification of negotiation opportunities is an important starting point for the

possible negotiations which can be performed.

The negotiation process can be put in order with the system. The negotiation is

organized in a well-structured process including preparation (with elaboration of the

BATNA), negotiation (with elaboration of a negotiation agenda, issue discussion and

exchanging offers and counter-offers), and with the final agreement through filling-

out the EFA.

Knowledge Management acting on whole process allows for the reuse of the

generated knowledge, facilitating the decision-making process and offering users a

negotiation environment in which it is possible to Negotiate and Learn to Negotiate

simultaneously.

The study can be analyzed under two points of view: the negotiation point of view

and the technological point of view. From the negotiation point of view, the

elaboration of a cooperative environment which allows for effective communication

among the users, sharing of knowledge and ordination of the process takes on great

importance in view of the great difficulty in establishing efficient decision-making

support and learning tools in the negotiations. From the technological point of view,

the proposed computing environment represents a challenge, as it involves the

integration of distinctive research areas: CSCW, E-Negotiation and Knowledge

Management.

It is important to emphasize that a culture fostering collaborative work and

increase of organizational knowledge constitutes the major factor for the success of

this kind of approach, and the adoption of this environment does not provide a

singular solution to all problems faced in a negotiation process. It is a resource to

improve the decisions and knowledge flow.

The next stage of this work comprises the implementation of the negotiation

environment to academic and research scenarios for evaluating our approach. We

envision deploying it to the community as a free platform.

Therefore, this work addresses a new context in which information technology

(IT) can add value, through KM and CSCW, by providing support to the Negotiation

Process between organizations, and facilitating process integration among them. As

future works, we have the development, implementation, adaptation and evaluation of

this environment in an experimental scenario. Currently, two areas are being

analyzed: negotiation for hydraulic resource allocation in river basin and negotiation

in the supply chain.

134

References

1. Acuff, F. L., “How to negotiate anything with anyone anywhere around the world”, New

York: American Management Association, 1993.

2. Barroso, A. C. O., Gomes, E. B. P., “Tentando Entender a Gestão de Conhecimento”.

Revista de Administração Pública, março/abril 1999 - vol. 33 - nº 2, p.147—170.

http://www.crie.ufrj.br. Accessed: Jan, 2004.

3. Bartolini, C., Preist., C. and Kuno, H., “Requirements for Automated Negotiation“,

http://www.w3.org/2001/03/ WSWS/popa/. Accessed: March, 2002.

4. Clarke., R, “Fundamentals of Negotiation”, Version: October, 1993.

http://www.anu.edu.au/people/Roger.Clarke/SOS/FundasNeg.html. Accessed: April,

2003.

5. Cybersettle: http://www.cybersettle.com, Accessed: Feb, 2004

6. Ellis, C.A., Gibbs, S. and Rein, G.L, “Groupware: Some Issues and Experiences”,

Communications of the ACM - January-Vol.34.No 1. 1991

7. Fisher, R. E, Ury, W., and Patton, B, “Getting to Yes: negotiating agreement without giving

in”. 2 ed., USA: Penguin Books, 1991.

8. Frappaolo, C. and Toms, W., “Knowledge Management: From Terra Incognita to Terra

Firma”, The Knowledge Management Yearbook 1999 – 2000, Butterworth – Heinemann,

USA, 2000.

9. Huang, P. C. K. and Mao, Ji-Ye, “Modeling e-Negotiation Activities with Petri Nets”. In:

Proceedings of the 35th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. HICSS 35.

Hawaii. 2002.

10. INSPIRE: http://interneg.org/interneg/tools/inspire/index.html, Accessed: Feb, 2004

11. Kersten, G. E and Noronha, S. J, “WWW-based negotiation support: design,

implementation, and use”. Decision Support Systems, v. 25, n. 2, p. 135-154, 1999.

12. Kersten, G. E and Noronha, S. J., “Negotiations via the Word Wide Web: A Cross-cultural

Study of Decision Making”. Group Decision and Negotiations, 8, p. 251-279, 1999.

13. Kersten, G., “The Science and Engineering of E-Negotiation: An Introduction”. In:

Proceedings of the 36th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, HICSS 36,

Hawaii. 2003

14. Lomuscio, A.R, Wooldridge and M. and Jennings, N. R, “A classification scheme for

negotiation in electronic commerce”. In: Agent-Mediated Electronic Commerce: A

European Agent Link Perspective, p. 19-33, 2001.

15. Martinelli, D. P. E and Almeida, A.P, “Negociação: Como transformar confronto em

cooperação”. São Paulo: Atlas, 1997.

16. Mills, H. A., “Negotiation: The art of Winning”. Gower Publishing Company Limited.

1991

17. Negoisst: http://www-i5.informatik.rwth-aachen.de/enegotiation/. Accessed: Feb, 2004

18. Nonaka, I. E a and TAKEUCHI, H., "The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese

Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation". Oxford Univ. Press. 1995.

19. Oliveira,J., Souza, J. and Strauch, J., "Epistheme: A Scientific Knowledge Management

Environment", ICEIS, Angers, France. 2003.

20. Raiffa, H, “The Art and Science of Negotiation”. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard

University Press. 1982.

21. Smartsettle: http://www.smartsettle.com, Accessed: Feb, 2004

22. Snowden, D., "A Framework for Creating a Sustainable Knowledge Management

Program". The Knowledge Management Yearbook 1999 - 2000, Butterworth – Heinemann.

2000.

23. Spangler, B, “Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement (BATNA)”.

http://www.beyondintractability.org/m/batna.jsp. Accessed: Feb, 2004.

24. WebNS: http://pc-ecom-07.mcmaster.ca/webns/, Accessed: Feb, 2004.

135