THE EFFECT OF ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE ON

KNOWLEDGE SHARING INTENTIONS AMONG

INFORMATION SYSTEM PROFESSIONALS

Jin-Shiang Huang

Department of Information Management, National Kaohsiung Marine University, 142 Hai Jhuan Rd., Kaohsiung, Taiwan

K

eywords: Knowledge Sharing, Organizational Culture, Competing Value Approach, IS Professionals

Abstract: On knowledge management discipline, little empirical research has been carried out to verify the differences

of knowledge sharing among individuals within different organizational settings. In the current study, theory

of Competing Value Approach (CVA) and knowledge classification structures from existing literature are

applied to conduct a conceptual framework to explore knowledge sharing intentions of different knowledge

categories for information system professionals from firms that exhibit various strengths on distinct cultural

dimensions. The hypothesized model is tested by Pearson correlation analysis and canonical analysis with

data from 172 full time workers of various job titles engaged in system development and maintenance

projects of different firms in Taiwan. Findings support the notion that knowledge sharing intentions of

information system professionals under distinct cultural types are quite different. Evidences also show that,

given the same organizational culture, the observed sharing intentions of various knowledge categories are

of equal level.

1 INTRODUCTION

With the highly dependence on information

technology for organizations, information systems

(IS) professionals responsible to perform activities

within system development life cycles are expected

to pursue project success by effective acquirement

and dissemination of knowledge among team

members composed of technical specialists and user

representatives (Nambisan and Wilemon, 2000).

Even if an organization determined to outsource the

whole system development activities, the firm

should assign experienced IS employees to

communicate both formally and informally with its

contractors for the purpose of enhancing system

usability and relationship maintenance (Lee, 2001).

Therefore, if knowledge sharing practices among IS

professionals were not seriously addressed, no

matter what system implementation strategy used,

the overall quality of the acquired system might

questionable. As the consequences, organizations of

the current century must exert all its strength to

initiate and promote effective knowledge sharing

environment for IS professionals and project

members in order to gain system success.

Many preliminary researches have explored

factors that may influence the knowledge sharing

intentions among colleagues from various theoretical

perspectives such as economic exchange, social

exchange and social cognition (Bock and Kim,

2002). However, it is our assertion that knowledge

sharing behaviors can not be made clear until

cultural effects are taken into account. The widely

accepted perspectives of theory of reasoned action

(TRA) and succeeding improvement from theory of

planned behavior (TPB) all emphasized that the

behavioral intention of a person was not influenced

only by her personal attitude toward the action, but

also by cultural level of concerns such as norms,

values and expectations (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975;

Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980). In specific, TRA and

TPB were able to be adopted to examine the

knowledge sharing behaviors among organizational

members, and from these theories, researchers

inferred that factors that facilitate knowledge sharing

behaviors were included in both individual and

cultural levels of an organization (Bock and Kim,

2002).

Organizational culture is the shared values in a

firm accumulated over time with the effort of its

founders and succeeding colleagues, and these

values are not able be changed in a short period of

419

Huang J. (2005).

THE EFFECT OF ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE ON KNOWLEDGE SHARING INTENTIONS AMONG INFORMATION SYSTEM PROFESSIONALS.

In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies, pages 419-424

DOI: 10.5220/0001229004190424

Copyright

c

SciTePress

time once established (Pettigrew, 1979). Therefore,

for organizations of specific cultural types,

knowledge sharing would become a common way to

deal with organizational affairs. On the contrary, if

negative appraisals toward knowledge dissemination

are prevailed in a firm, the knowledge sharing

practices would never be accepted by its

organizational members (Janz and Prasarnphanich,

2003). Base on the above inferences, the main

purpose of this study is to understand the influence

of organizational culture on knowledge sharing

intentions among IS professionals. The rest of this

study is organized as follows. First, the potential

differences of knowledge sharing among various

cultural types are explored by extending current

understandings from literature review, followed by

the formulation of research hypotheses. A filed

survey will succeeded to examine and test the

proposed hypotheses, and the discussions and

conclusions derived from these findings will be

made.

2 ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE:

THE COMPETINT VALUE

PERSPECTIVE

The definitions of organizational culture are

relatively complex. In order to lower the degree of

abstraction and to fit the requirement of distinct

needs, researchers were apt to apply unique ways to

observe and classify organizational culture. Among

many candidates, we consider CVA is a suitable

perspective to understand the effects of

organizational culture on knowledge sharing since

CVA has its theoretical backgrounds in human

information processing, a behavioral observation

that focus on the various needs of information

immediacy and certainty (Deal and Kennedy, 1984),

and knowledge sharing is also an action of human

information processing that may take these needs

into account.

According to CVA, organizational culture can

be classified by considering the relative importance

of procedural flexibility as the vertical axis, and the

degree of external orientation within organizational

information processing as the horizontal axis (Quinn

and McGrath, 1985). Four typical organizational

cultural types were identified according to this

classification framework as shown below. The

ideological culture was characterized by pursuing

innovation, taking adventures and requesting of

growth for organization members who utilize their

intuitions, insights, and values to make decisions to

catch up with the migration of external

environments. The consensual culture addressed the

importance of internal cohesion and harmonious

atmosphere toward reaching consensus by informal

and flexible forms of participations for all

organizational members. In the typical hierarchical

culture, however, obedience was the only virtue.

Each person was required to apply internal rules,

codes or orders from upper levels to deal with

organizational problems. The rational culture

regarded goal achievements and competitiveness as

the most essential elements for organizational

success. Under the rational culture, members were

asked to make effort in raising their operational

efficiency and productivity to maximize

organizational profits and their personal welfare.

3 KNOWLEDGE FRAMEWORK

FOR IS PROFESSIONALS

Knowledge is a multi-facet concept in its nature

(Nonaka, 1994). Elements such as facts, skills,

cognitions and procedures may all contribute to

some parts of organizational knowledge (Snyder,

1996). Therefore, to better understand the

knowledge sharing behaviors of organizational

members, a knowledge classification framework is

required to distinct the sharing intention of a specific

knowledge category from that of others. Numerous

works categorised organizational knowledge using

either the content attribute of know-that / know-how

(Ryle, 1975), or the presentation format of explicit /

tacit (Polanyi, 1966). In specific, know-that is the

knowledge about beliefs, intuition and cognition of a

person, while know-how represents the knowledge

of physical or mental execution; implicit knowledge

can not be stated or organized by words obviously,

while explicit knowledge can be edited or explained

by written language. Taking the above content

attributes and presentation formats into account

simultaneously, four typical types of organizational

knowledge can be identified, namely, explicit know-

that, tacit know-that, explicit know-how, and tacit

know-how.

4 RESEARCH HYPOTHESES

Organizational culture is believed to have significant

impacts on the behavior of employees since a firm’s

common value and attitude would ultimately

dominate the formation of individual value, attitude

and behavior (Steers and Porter, 1991). Therefore, if

a common value of an organization is to share

opinions with each other, the members will get used

WEBIST 2005 - SOCIETY AND E-BUSINESS

420

to share their personal ideas in the long run (De

Long and Fahey, 2000). The above concept was also

supported by the results of a literature survey which

revealed that the successful knowledge management

practices and the advances of knowledge sharing

activities were highly associated with their

organizational culture (Alavi and Leidner, 2001).

Under ideological culture, employees pursue

organizational success through innovations derived

from insights and intuitions. Since ideologies, values

and insights are highly individualized and can hardly

be manipulated or explained, these personal

belongings were often categorized as “tacit” rather

than “explicit” (Snyder, 1996). Therefore, we infer

that organizations of ideological culture are willing

to encourage their employees to share all their

personal tacit knowledge mutually.

[H1] The strength of a firm’s ideological

culture will positively influence the

sharing intention of tacit know-that and

tacit know-how knowledge for its IS

professionals.

Consensual culture addresses the importance of

group cohesion and harmonious atmosphere. Firms

of consensual culture always make the final

decisions by sharing and discussing all information

and knowledge available from each participant for

the purpose of achieving consensus (Storck and Hill,

2000). Thus, we hypothesize that the consensual

culture will sustain an environment for members to

exchange their personal ideas or feelings no matter

what category the knowledge is belonging to.

[H2] The strength of a firm’s consensual

culture will positively influence the

sharing intention of all four knowledge

categories for its IS professionals.

Hierarchical culture implies a top-down

management style in which only the persons on top

of the pyramid have the authority to create and share

knowledge, and followers should obey formal orders

from their superiors without reservation. Since the

hierarchical control mode is apt to ignore the

existence of tacit knowledge and skills from basic

levels, hierarchical firms request their employees to

exchange explicit rather than tacit knowledge

according to formalized rules (Nonaka and

Takeuchi, 1995). Base on the above inference, we

propose the following hypothesis:

[H3] The strength of a firm’s hierarchical

culture will positively influence the

sharing intention of explicit know-that

and explicit know-how knowledge for its

IS professionals.

Rational culture regards goal-achieving as the

only objective for firms. Since it address the value of

competition and individualization, organization

members tend to complete their tasks all by

themselves without seeking support from others.

Therefore, individuals under rational culture are not

willing to share whatever they know to each other

for the sake of sustaining their personal

competitiveness, which may limit the diffusion and

application of knowledge dramatically (Probst et al.,

2000). The following hypothesis is derived.

[H4] The strength of a firm’s rational culture

will negatively influence the sharing

intention of all four knowledge

categories for its IS professionals.

5 MEASURES

Organizational culture was measured using

questions from Cameron (1985). Rooted in CVA,

the questionnaire determined the strength of each

culture type for a firm by evaluating six cultural

dimensions which include dominant characteristics,

organizational leader, organizational glue,

organizational climate, criteria of success and

management style. Typical scenarios for all cultural

type in each dimension were offered to determine

the cultural similarity among an observed firm and

four exemplary firms of distinct culture types.

Knowledge items required by IS professionals

for each knowledge category were adopted from

Zmud (1983). In its original form, thirty IS related

knowledge items were classified into six categories:

knowledge of organizational overview,

organizational skills, target organizational unit,

general IS concepts, technical skills and IS products.

In order to fit know-that / know-how and explicit /

tacit knowledge framework used in this study, the

author and three independent coders separately

classified these thirty items into four knowledge

categories according to their contents and major

presentation formats. For the purpose of objectivity,

only knowledge items categorized into the same

knowledge category by all coders (shown in Table

1) were retained for further use. The sharing

intention of each retained knowledge item was

measured by a 5-point Likert scale question which

ranked the sharing willingness of respondents from

strongly disagree to strongly agree.

THE EFFECT OF ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE ON KNOWLEDGE SHARING INTENTIONS AMONG

INFORMATION SYSTEM PROFESSIONALS

421

Table 1: Knowledge items retained in this study

Knowledge

categories

Items retained

Explicit know-that Primary organizational functions

Work unit objectives

IS policies and plans

Tacit know-that IS/IT for competitive advantage

Fit between IS and organization

IS/IT potential

Critical success factors

Work unit problems

Environmental constraints

Explicit know-how Use of office automation products

Use/understand documentation

IS evaluation and maintenance

Use of operating systems

Use of specific application systems

Preparation of documentation

Tacit know-how Model application

Interpersonal communication

Group dynamics

Project management

6 DATA COLLECTION

Questionnaires were sent to project members of

major IS providing companies in Taiwan whose

contact information were available on companies’

websites. A total of 1031 e-mail surveys were sent

out in 2004 and with 172 returned for a response rate

of 16.7%. Table 2 portraits the respondents’

demographic dispersions. The distributions of these

attributes were roughly consistent with the official

statistics of IT related workers released by Institute

for Information Industry in Taiwan.

Respondents also reported the strength of each

culture type for their organizations. If counted on the

base of the strongest culture type, 58 reported their

organizational culture as the consensus culture, 20

reported as ideological culture, 68 as hierarchical

culture, and 26 as rational culture. The dispersions

reveal that our sampling firms are mainly equipped

with consensus or hierarchical characters.

7 RESULTS

The Pearson correlation coefficients shown in Table

3 offered some preliminary evidences toward

understanding the potential relationship between the

strength of organizational cultures and the sharing

intentions of each knowledge category. The

correlation results revealed that the stronger the

consensual culture, the higher level of sharing

intention is for all four knowledge categories,

therefore supporting H2. A rational culture was also

found to be negatively correlated with the sharing

intentions for all knowledge categories, supporting

H4 as expected. However, the proposed relationship

between ideological culture and sharing intentions of

tacit knowledge was not supported. The relationship

between hierarchical culture and sharing intentions

of explicit knowledge was also untenable. Both H1

and H3 should be rejected accordingly.

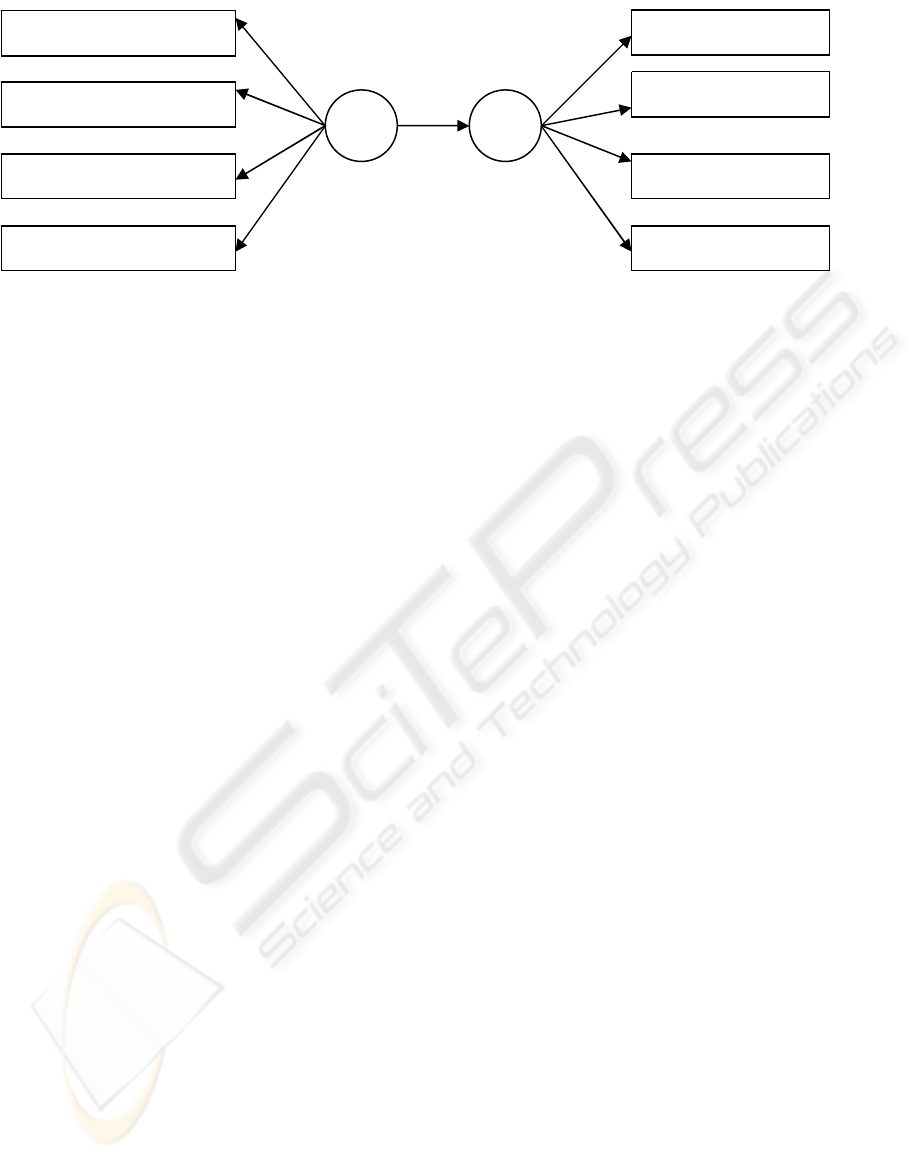

A further analysis was conducted by applying

canonical analysis to determine the potential causal

effects between the linear combination of four

cultures and the similar combination of four

knowledge categories. The results shown in Figure 1

delineated that only one set of canonical correlation

(with eigenvalue > 0.1) was found between

organization cultures and knowledge categories. The

explanation of this finding was that as the intensity

of consensual culture strengthened or the intensity of

rational culture weakened, the knowledge sharing

intentions of all knowledge categories for IS

professionals shall be enhanced accordingly, which

is similar to the Pearson correlation results.

Table 2: Demographic dispersions of respondents

Attributes Classifications Number Percentage

(%)

Sex Male

Female

101

71

58.7

41.3

Education Junior college

University

Graduate Study

37

119

16

21.5

69.2

9.3

Job title Programmer

Technical specialist

65

42

37.8

24.4

System analyst

End user consultant

Others

28

15

22

16.3

8.7

12.8

Table 3 Results of Pearson correlation analysis

Consen.

Intensity

Ideolog.

intensity

Hierarc.

intensity

Ration.

intensity

Explicit

know-how

0.257** 0.015 0.089 -0.222**

Tacit

know-how

0.280** 0.063 0.024 -0.196*

Explicit

know-that

0.282** 0.020 0.017 -0.188*

Tacit

know-that

0.264** 0.045 0.031 -0.202*

* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level

WEBIST 2005 - SOCIETY AND E-BUSINESS

422

Figure 1: The results of canonical analysis

8 DISCUSSIONS AND

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings confirmed that the strength of

consensual culture would positively influence the

knowledge sharing intention of all knowledge

categories for IS professionals. This aspect is

consistent with the notion that the knowledge

oriented behaviors shall take place when there is full

of common values among organizational members

(De Long and Fahey, 2000). Therefore, it is

suggested that good personal relationship is ought to

be established and maintained within the

organization for the sake of enhancing knowledge

sharing intentions for IS professionals.

The strength of rational culture that addresses

the value of individualization was found to be

negatively influence the sharing intention of all

knowledge categories for IS professionals.

Researches suggested that in order to transfer

knowledge to other individuals, organizations should

inaugurate regular group discussions or community

oriented exchange platforms to ensure the

effectiveness of knowledge sharing activities

(Devenport and Prusak, 1998). Organizations are

also advised to adopt team-based rather than

individual-based motivation systems to avoid the

reservation of personal knowledge (Gupta and

Govindarajan, 2000). Thus, for organizations that

aimed at pursuing extensive knowledge sharing

among IS professionals, effective ways must be

carried out in advance to reduce the strength of

rational culture within their firms.

The hypothesized effect of the strength of

hierarchical culture on sharing intention of explicit

knowledge was not supported. A possible

explanation for the phenomenon was that the

behavioral intention of subordinates in hierarchical

culture depended heavily on the attitude of their

leaders (Quinn, 1988), which implied that, under

hierarchical culture, the knowledge sharing intention

of IS professionals may also depended heavily on

the opinions of chief executives. If organizational

leaders did not recognized the sharing behaviors of

explicit knowledge, although available in its natural

settings, IS professionals should behaved comply

with their superiors. Further studies are needed to

examine the potential moderating effect from high-

level in hierarchical culture.

Hypothesis related with ideological culture also

gained little empirical support in this study. Since

ideological firms innovated themselves merely

through individual insights and intuitions, the main

focus for their knowledge management activities

might be allocated to knowledge creation rather than

knowledge sharing. A recent survey found that the

major missions of knowledge management for many

technology oriented firms were enriching their

knowledge seeking and knowledge constructing

capabilities, which may often be completed by

independent employees (Murray, 2001). To

demonstrate the inferential rationality, the soundness

of this interpretation should be carefully examined

by further discussions.

Our findings showed that the knowledge

sharing intention of IS professionals under various

cultural types were quite different. With the above

idea in mind, knowledge management practitioners

should bring up unique ways to facilitate knowledge

sharing activities for each distinct organizational

culture type. However, since this study examined the

organizational culture dimension merely using CVA,

researches based on other cultural perspectives are

necessary to broaden the current understanding of

the overall effects of organization culture on

knowledge sharing behavior for IS professionals.

The attempt toward understanding the

relationship between knowledge sharing intentions

and cultural elements is at its very beginning.

0.507

0.022

0.105

-0.397

0.857

0.882

0.895

0.61*

(p<0.05)

η

1

χ

1

Explicit know-that

0.962

Consensual intensity

Ideological intensity

Hierarchical intensity

Rational intensity

Tacit know-how

Tacit know-that

Explicit know-how

THE EFFECT OF ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE ON KNOWLEDGE SHARING INTENTIONS AMONG

INFORMATION SYSTEM PROFESSIONALS

423

Further investigations might be carried out to re-

examine our findings by enlarging sample sizes,

improving response rate, or observing longitudinally.

Future research opportunities also exist to explore

and compare the knowledge sharing intentions of IS

professionals under numerous countries or regions

that withhold various value systems.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to thank three anonymous

reviewers for their comments on the manuscript. The

research was founded by a grant to the author from

National Science Council (Taiwan) under the

contract number NSC 93-2416-H-022-003.

REFERENCES

Alavi, M., and Leidner, D. (2001). Review: Knowledge

Management and Knowledge Management Systems:

Conceptual Foundations and Research Issues. MIS

Quarterly, (25)1, 107-137.

Ajzen, I. and Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding

Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior, Prentice-

Hall. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.

Bock, G..W. and Kim, Y. (2002). Breaking the Myths of

Rewards: An Exploratory Study of Attitudes about

Knowledge Sharing. Information Resources

Management Journal, 15(2), 14-21.

Cameron, K.S. (1985). Cultural Congruence Strength and

Type: Relationship to Effective, In E. Robert and

Quinn. (eds.), Beyond Rational Management, 142-143.

Deal, T.E., and Kennedy, A. (1984). Corporate Cultures.

Commonwealth.

De Long, D.W., and Fahey, L. (2000). Diagnosing Cultural

Barriers to Knowledge Management, Academy of

Management Executive, 14(4), 113-127.

Davenport, T. H., and Prusak, L. (1998). Wo r ki n g

Knowledge, Harvard Business School Press. Boston.

Fishbein, M. and Ajzen, I. (1975). Beliefs, Attitude,

Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and

Research. Addison-Wesley.

Gupta, A. K, and Govindarajan, V. (2000). Knowledge

Management’s Social Dimension: Lessons from Nucor

Steel, Sloan Management Review, 42(1), 71-80.

Janz, B.D., and Prasarnphanich, P. (2003). Understanding

the Antecedent of Effective Knowledge Management:

The Importance of a Knowledge-Centered Culture,

Decision Sciences, 34(2), 351-384.

Lee, J. (2001). The Impact of Knowledge Sharing,

Organizational Capability and Partnership Quality on

IS Outsourcing Success, Information and Management,

38(5), 323-335.

Murray, J.Y. (2001). Strategic alliance-based global

sourcing strategy for competitive advantage: A

conceptual framework and research propositions,

Journal of International Marketing, 9(4), 30-58.

Nambisan, S. and Wilemon, D. (2000). Software

Development and New Product Development:

Potentials for Cross-Domain Knowledge Sharing,

IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management,

47(2), 211-220.

Nonaka, I. (1994). A Dynamic Theory of Organizational

Knowledge Creation, Organization Science, 5(1), 14-

37.

Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H., (1995). The Knowledge-

Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create

the Dynamics of Innovation. Oxford University Press,

New York.

Pettigrew, A.M. (1979). On Studying Organizational

Cultures, Administrative Science Quarterly, 23(2),

570-581.

Polanyi, M. (1966). The Tacit Dimension. Anchor

Doubleday Books, New York.

Probst, G., Raub, S., and Romhardt, K. (2000). Managing

Knowledge. Wiley, New York.

Quinn, R.E. (1988). Beyond Rational Management:

Mastering the Paradoxes and Competing Demands of

High Performance. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

Quinn, R.E. and McGrath, M.R. (1985). The

Transformation of Organizational Cultures: A

Competing Value Perspective. In P.J. Forst, L.F. Morre,

M.R. Louis, C.C. Lundberg, J. Martin (eds.),

Organizational Culture. SAGE, Beverly Hills, CA.

Ryle, G. (1975). The Concept of Mind. Hutchinson & Co,

London.

Storck, J., and Hill, P. A. (2000). Knowledge Diffusion

through Strategic Communities, Sloan Management

Review, 42(2), 63-74.

Snyder, W. M. (1996).

Organization Learning and

Performance: An Exploration of the Linkages between

Organization Learning, Knowledge and Performance.

Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of

Southern California.

Steers, R.M., and Porter, L.W., (1991). Motivation and

Work Behavior, McGraw-Hill. New York, 5

th

edition.

Zmud, R.W. (1983). Information Systems in Organizations,

Scott, Foresman and Company. Tucker, GA.

WEBIST 2005 - SOCIETY AND E-BUSINESS

424