IDENTIFYING FACTORS IMPACTING ONLINE LEARNING

Dennis Kira, Raafat George Saadé and Xin He

Department of Decision Sciences and MIS,

John Molson School of Business,

Concordia University, Quebec, Canada

Keywords: Dimensions, Affect, Perceptions, Motivation, Learning Attitudes.

Abstract: The study presented in this paper sought to explore several dimensions to online learning. Identifying the

dimensions to online learning entails important basic issues which are of great relevance to educators today.

The primary question is “what are the factors that contribute to the success/failure of online learning?” In

order to answer this question we need to identify the important variables that (1) measure the learning

outcome and (2) help us understand the learning experience of students using specific learning tools. In this

study, the dimensions we explored are student’s attitude, affect, motivation and perception of an Online

Learning Tool usage. A survey utilizing validated items from previous relevant research work was

conducted to help us determine these variables. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used for a basis of

our analysis. Results of the EFA identified the items that are relevant to the study and that can be used to

measure the dimension to online learning. Affect and perception were found to have strong measurement

capabilities with the adopted items while motivation was measured the weakest.

1 INTRODUCTION

The opportunities for learning and growth of online

are virtually limitless. Internet-based education

transcends typical time and space barriers, giving

students the ability to access learning opportunities

day and night from every corner of the globe.

Coursework can now provide material in highly

interactive audio, video, and textual formats at a

pace set by the student.

In one decade since the coding language for the

World Wide Web (WWW) was developed,

educational institutions, research centers, libraries,

government agencies, commercial enterprises,

advocacy groups, and a multitude of individuals

have rushed to connect to the Internet. One of the

consequences of this tremendous surge in online

communication has been the rapid growth of

technology-mediated distance learning at the higher

education level.

Individuals are continuously using the Internet to

perform a wide range of tasks such as research,

shopping and learning. In particular, during the last

decade Information Technology (IT) has been the

primary force driving the transformation of roles in

the education industry. More specifically, the World

Wide Web (WWW) and associated technologies

provided a new environment with new rules and

tools to conduct instruction and create novel

approaches to learning. With the evolution of the

WWW we saw education marketed as long distance

learning, web based learner centered environments,

internet based learning environments, and self

instructed learning. With all the different models

used on the web, few have studied their acceptance

and their effectiveness on learning.

Education has expanded from the traditional in-

class environment to the new digital phenomenon

where teaching is assisted by computers (Richardson

and Swan, 2003). Today, we find a vast amount of

courses, seminars, certificates and other offerings on

the Internet. This wave of educational material and

online learning tools has challenged the

effectiveness of the traditional educational approach

still in place at universities and other education

institutions. Consequently, these institutions are

struggling to redefine and restructure their strategies

in providing education and delivering knowledge.

With today’s student demographics, educational

institutions are rushing to meet the needs of the new

learner by designing and setting up online learning

tools as support to the computer assisted classroom.

Online education is often defined as an approach

to teaching and learning that utilizes Internet

technologies to communicate and collaborate in an

457

Kira D., George Saadé R. and He X. (2005).

IDENTIFYING FACTORS IMPACTING ONLINE LEARNING.

In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies, pages 457-465

DOI: 10.5220/0001232904570465

Copyright

c

SciTePress

educational context. This includes technology that

supplements traditional classroom training with

web-based components and learning environments

where the educational process is experienced online.

Online learning tools are any web sites, software, or

computer-assisted activities that intentionally focus

on and facilitate learning on the Internet (Poole,

Jackson, 2003). Learning tools that have been

investigated by researchers include web based

dynamic practice system, multimedia application

and game based learning modules (Saadé, 2003,

Sunal et al., 2003, Poole et al., 2003, Eklund and

Eklund, 1996, Irani, 1998). These learning tools

focus on specific learning aspects and try to meet the

learning needs of a particular group of learners.

With the wide use of technology in today’s

learning environment, we should not anymore be

concerned with finding out which is better, face-to-

face or technology-enhanced instruction (Daley et al,

2001). In fact, student’s experience with a course

does not only entail the final grade but how much of

the learning objectives have been attained. Also,

holistic experiences with the course should be

emphasized. Online learning presents new

opportunities to engage more with the students and

student-centered learning, thereby enhancing the

learning experience. Our primary goal should be

whether students really learn with the intervention of

online learning tools. If yes, what are the variables

that contribute to the success of online learning

tools? If no, then what is going wrong and how can

we enhance the learning tool in question? To

understand the process of learning using online

learning tools, we need to identify the important

variables that measure the learning outcome of

students using a specific learning tool, and also the

variables that help us understand students’ learning

experience with the learning tool.

In essence, learning is a remarkably social

process. In truth, it occurs not as a response to

teaching, but rather as a result of a social framework

that fosters learning. To succeed in our struggle to

build technology and new media to support learning,

we must move far beyond the traditional view of

teaching as delivery of information. Although

information is a critical part of learning, it’s only

one among many forces at work. It’s profoundly

misleading and ineffective to separate information,

theories, and principles from the activities and

situations within which they are used. Knowledge is

inextricably situated in the physical and social

context of its acquisition and use.

From examining previous literature, we

identified six variables that are considered to be

important by researchers to the learning outcome

and learning experience with online learning tools.

These variables are an affect, a learner’s perception

of the course, a perceived learning outcome, an

attitude, an intrinsic motivation and an extrinsic

motivation. In this study, a survey methodology was

followed. We adopted items (questions) for these

variables from different studies and performed an

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) to test the

validity of the variable sets in the present context. It

is the objective of this paper to identify those

variables that may play a significant role in learning

while using online learning tools.

A recent study performed by (Sunal et al., 2003)

analyzed a body of research on best practice in

asynchronous or synchronous online instruction in

higher education. The study indicated that online

learning is viable and resulted in the identification of

potential best practices. Most studies on student

behavior were found to be anecdotal and are not

evidence based. Researchers today are concerned

with exploring student behavior and attitudes

towards online learning. The evaluation of behavior

and attitude factors is not well developed and scarce.

Motivated by the need for more concrete and

accurate evaluation tools, we identified six important

factors that may be used to better understand student

behavior and attitude towards online learning. These

factors which we shall refer to as the dimensions to

online learning are affect, perception of course,

perceived learning outcome, attitude, intrinsic

motivation and extrinsic motivation.

Affect: Affect refers to an individual’s feelings of

joy, elation, pleasure, depression, distaste,

discontentment, or hatred with respect to particular

behavior (Triandis, 1979). Triandis (1979) argued

that literature showed a strong relationship between

affect and behavior. In a business context, it was

observed that positive relation between affect and

senior management’s use of executive information

system exists. Positive affect towards technology

leads gaining experience, knowledge and self-

efficacy regarding technology, and negative affect

causes avoiding technology, thereby not learning

about them or developing perceived control

(Arkkelin, 2003).

Learner’s Perception of the Course: Student’s

perceptions of using technology as part of the course

learning process was found to be mixed (Piacciano,

2002, Kum, 1999). Some students were

uncomfortable with the student-centered nature of

the course and were put-off by the increased

demands of the computer-based instruction, which

reduced student engagement in the course and led to

a decline in student success (Lowell, 2001).

Learners’ perception of the course may influence

behavior due to the non-familiarity with the learning

tool used. Until students fully understood what was

WEBIST 2005 - E-LEARNING

458

expected of them, they often acted with habitual

intent based on an imprecise understanding or

perception of the course (Davies, 2003).

Perceived learning Outcome: Perceived learning

outcome is defined as the observed results in

connection with the use of learning tools. Perceived

learning outcome was measured with three items: 1)

performance improvement; 2) grades benefit; and 3)

meeting learning needs. Previous studies have

shown that perceived learning outcomes and

satisfaction are related to changes in the traditional

instructor’s role from leader to that of facilitator and

moderator in an online learning environment

(Feenberg, 1987; Krendl and Lieberman, 1988;

Faigley; 1990). Researchers also reported that

students who have positive perceived learning

outcome may have more positive attitudes about the

course and their learning, which may in turn cause

them to make greater use of the online learning

tools.

Attitude: Most of the online learning literature

concentrates on student and instructor attitudes

towards online learning (Sunal et al., 2003).

Marzano and Pickering (1997), indicated that

students’ attitude would impact the learning they

achieve. Also research has been conducted to

validate this assertion and extends this assertion into

an on-line environment (Daley et al, 2001).

Moreover, Technology Acceptance Model (TAM)

(Davis et al., 1989) also suggests that attitudes

towards use directly influence intentions to use the

computer and ultimately actual computer use. Davis

et al. (1989) demonstrate that an individual's initial

attitudes regarding a computer's ease of use and a

computer's usefulness influence attitudes towards

use.

Intrinsic Motivation: Researchers also studied

motivational perspectives to understand behavior.

Davis et al. (1992) have advanced this motivational

perspective to understand behavioral intention and to

predict the acceptance of technology. They found

intrinsic and extrinsic motivation to be key drivers

of behavioral intention to use (Venkatesh 1999,

Vallerand, 1997). Wlodkowshi (1999) defined

intrinsic motivation as an evocation, an energy

called forth by circumstances that connect with what

is culturally significant to the person. Intrinsic

motivation is grounded in learning theories and is

now being used as a construct to measure user

perceptions of game/multimedia technologies

(Venkatesh 1999, Venkatesh and Davis, 2000,

Venkatesh et al. 2002).

Extrinsic Motivation: Extrinsic motivation was

defined by (Deci and Ryan, 1987) as the performing

of a behavior to achieve a specific reward. In

students’ perspective, extrinsic motivation on

learning may include getting a higher grade in the

exams, getting awards, getting prizes and so on. A

lot of research has already verified that extrinsic

motivation is an important factor influencing

learning. However, other research also addresses

that extrinsic motivation is not as effective as

intrinsic motivation in motivating learning or using

technology to facilitate learning.

2 METHODOLOGY

An exploratory factor analysis approach was

followed to test the validity of the dimensions of

online learning. The EFA mathematical criteria were

used to create factor models from the data. It

simplifies the structure of the data by grouping

together observed variables that are inter-correlated

under one “common” factor (or in the context of this

study, dimension). Prior to the presentation of the

EFA approach and results, we describe the tool used,

the experimental setup including participants and

procedure and the questionnaire used.

2.1 The Online learning tool

The Online Learning Tool was developed so that

students could practice and then assess their

knowledge of content material and concepts in an

introductory management information systems

course. The learning tool helps students rehearse as

well as learn by prompting them with multiple-

choice, and true or false questions. The learning tool

is web based and can be accessed using any web

browser. Selection of the web to implement the

learning tool is appropriate due to the fact that the

technology is available from many locations around

the campus, friends, internet cafes and homes, thus

access would not count as a barrier to the usage of

the technology.

The learning tool is programmed using html and

scripting languages with active server pages (ASP)

support to communicate with the database. The html

and ASP files are very simple in design and do not

include graphics and images or any other distracting

objects. Each page includes one or two buttons that

students can click on. This design allows the student

to focus on the task at hand and away from

exploration.

The learning tool is made up of three

components: (1) the front end which interacts with

the user, (2) the middle layer which stores and

IDENTIFYING FACTORS IMPACTING ONLINE LEARNING

459

controls the interaction session and (3) the back end

which includes the database with questions. The

front end is simple and allows the student to log into

the web site and select whether he/she wants to

practice or get evaluated. The middle layer keeps

track of the student’s performance as well as

controls the logic behind the selection of the

questions from the database and prompting them to

the student. The back end (database) contains the

multiple choice and true or false pools of questions

students’ answers to the questions and time that they

spent answering each set of questions.

Since the Online Learning Tool was developed

for the web, students were able and allowed to use

the system anywhere, anytime. The system would

monitor students’ activities such that usage time,

chapters accessed and average scores per chapter

were stored and time stamped. Due to the fact that

the internet is widely used among students, the

selection of the web to implement the Online

Learning Tool is justified. Furthermore, the web

technology exemplifies the characteristics of

contemporary information technology and that the

technology is available from many locations around

the campus, friends, Internet cafes and homes.

Therefore access would not count as a barrier to the

usage of the technology.

Students were asked to use the Online Leaning

Tool and informed that this portion of the course to

count for 10% of their final mark. The remaining

part of the course grade was distributed between a

midterm exam (25%), a project (20%) and a final

exam (45%). The Online Learning Tool interface

was simple and contained two major components.

The first component included a practice engine

where students would practice multiple choice, and

true or false questions without being monitored or

having any of their activities stored. The second

component entails a test site similar to what the

students have used in component 1. Both parts have

the same interface, engine and pool of questions.

The Online Learning Tool is integrated in the

instructional design of the course with some

pedagogical elements in mind. First, the questions in

the practice (Component 1) and assessment

(Component 2) components of the Online Learning

Tool are retrieved from the same pool in the

database. This implies that some questions will

repeat and therefore encourage students to use their

cognitive skills such as short-term memory, working

memory, recognition and recollection. This is

especially true because the students are notified that

the pool of questions is fixed and that questions will

reappear. That is, students need to be very attentive

during the exercise/practice process. Questions

included multiple choice, and true or false and

students were given immediate feedback to their

responses. Second, the assessment (component 2) of

the students’ level of acquired knowledge found in a

specific chapter of the course is not limited by the

number of questions that the students are asked to

answer but only by their willingness to practice.

Students have the flexibility to answer as many

questions as they wish. In other words, students have

the choice to practice again and be re-assessed

(tested) as many times as they wish. The final

assessment mark, however, is calculated as the

average of all the assessments taken. For example,

the student is required to do a minimum of 20

questions. If the student after answering 20

questions receives an average of 75% and the

students wishes to increase this average, then the

student may practice some more (using component

1) and then return to the assessment part (component

2) and re-attempt 10 more questions. If the student

score 80% on the second set of questions, then the

running average of the student is (80+75)/2 = 77.5%.

Third, the answer to a few questions in every chapter

was intentionally specified wrong. That is, if the

student selects the correct answer, the Online

Learning Tool will tell the student that the answer is

wrong. Students are notified about this fact and are

encouraged to find those errors and report them.

Students are given bonus points for finding those

wrong questions/answers.

2.2 Participants and Procedure

A total of 105 undergraduate students participated in

using the Online Learning Tool. The students’

sample represents a group:

• 37% between the ages of 18 and 22, 21%

aged between 22 and 24 years and 32%

above 26 years old;

• with a majority (57%) claiming to have 2 to

5 years of experience using the internet and

33% claiming to have more than 5 years of

internet experience ;

• with the majority (90%) indicating that they

use the internet more than 1 hour a day.

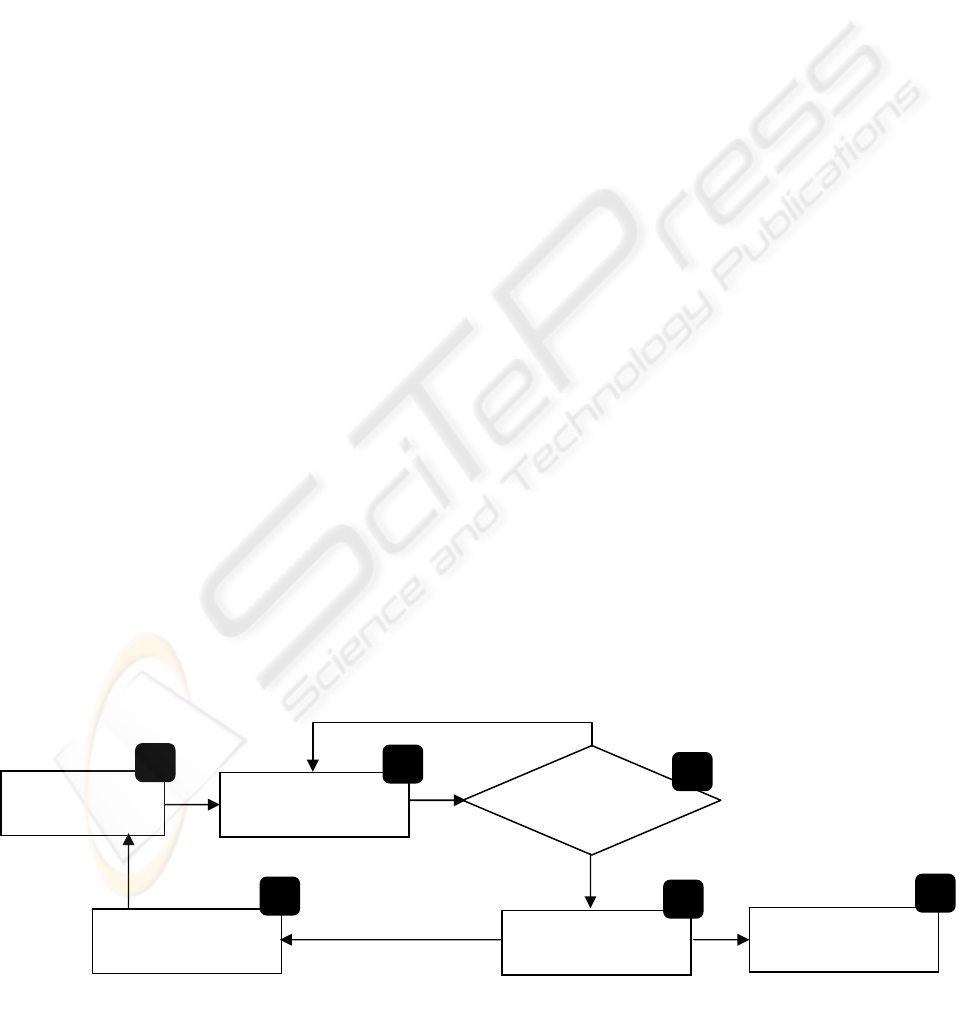

A flowchart describing the suggested students’

learning process with the Online Learning Tool

integrated is shown in figure 1 below. Steps 1 to 5

are a cycle that needs to be followed for every

chapter. First, the student should study chapter C(i)

prior to the use of the Online Learning Tool (step 1).

Once the student has studied chapter C(i), he/she can

login (via the internet) and select to practice

WEBIST 2005 - E-LEARNING

460

answering questions ‘P(i,j,k)’ associated with the

chapter ‘i’ studied, where ‘j’ and ‘k’ represent

multiple choice and true or false questions

respectively (step 2). The practicing component

prompts the student with a set of five questions at a

time. The student answers the questions and requests

to be evaluated. The Online Learning Tool then

identifies the correct from the incorrect answers. The

student can verify the results and when ready click

on the ‘Next’ button to be prompted with another

randomly selected set of questions (step 2). The

student can practice as much as he/she feels is

necessary (step 3), after which he/she can do the test

for the specific chapter T(i,j,k) (step 4). The student

can then continue with another cycle identified by a

new chapter to study and practice (step 5). At any

time, a student can request an activity report which

includes a detailed view of what and how much they

practices and a summary report which provides them

with running average performance data.

2.3 Questionnaire

Validated constructs were adopted from different

relevant prior research work (Venkatesh et al., 2003,

Agarwal and Karahanna, 2000, Davis, 1989). The

wording of items was changed to account for the

context of the study. All items shown in the

appendix were measured using a 5-point scale with

anchors all of the questions from “Strongly

disagree” to “Strongly agree” with the exception of

‘learners’ perception of course’ which had anchors

between 0% and 100%. The questionnaire included

items worded with proper negation and a shuffle of

the items to reduce monotony of questions

measuring the same construct.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Student Feedback on Affect

(AFF)

The Affect reported by the sample students is not

positive. More than 50% of the students reported

that they feel the “learning tool” to be a nuisance.

40% of them also reported frustration in using the

“learning tool”. The same number of the students

reported anxiety and tension in using the “learning

tool”. The negative affect in using the “learning

tool” was not due to technical problems since very

little technology related problems were reported.

Student most probably had negative affect due to the

fact that the course (which is also reflected in the

number of chapters to practice for) contained a large

amount of information. This was previously

observed where negative affect has caused the

student to avoid the use of the “learning tool”

(Arkkelin, 2003). In the present study, students

continued using the learning tool because their

scores were part of their final mark (5%).

3.2 Student Feedback on Learners’

Perception on Course (PC)

The perception on the course was positive. More

than 50% of the students indicated that the learning

tool is important for the course. Closer to 95% of the

students felt that they will score above 50% in the

course with half of them expecting a mark above

75%. Approximately 75% of the students seemed to

invest more than 50% of their efforts on this course.

In relation to the course material, nearly 60% of the

students felt that compared to other courses, this

course on the average has 75% more valuable

content, at the same time 75% more difficult and

that they were 75% more enthusiastic in taking the

course.

Study

Chapter C(i)

Practice

Questions P(i,j,k)

Assess T(i,j,k)

Ready for test

T(i,j,k) ?

No

Yes

Go to

next

Chapter (i)

Reports on

P(i,j,k) & T(i,j,k)

1

2

3

4

5

6

Figure 1: The Online Learning Tool process

IDENTIFYING FACTORS IMPACTING ONLINE LEARNING

461

3.3 Student Feedback on Attitude

(ATT)

Close to 60% of the students found that “learning

tools” are helpful in better understand course

content. Also 60% of the students reported the

advantages of “learning tools” overweigh the

disadvantages. Most students felt that the “learning

tool” had little influence in improving their

interaction with other fellow students, in helping

their performance in other courses, and in feeling

more productive by using it. These results were

expected due to the fact that the

“learning tool” targeted student’s learning of

specific topics in relation to the present course and

not other courses. Also, the “learning tool” was not

designed to enhance collaboration among students.

What is interesting is that 10% of the students

actually did feel that the “learning tool” will help

them in other courses, claimed that it improved the

quality of interaction with other students and felt

that they were more productive using it.

3.4 Student Feedback on Perceived

Learning Outcome (PLO)

As shown, perceived learning outcome is very

positive. More than 60% of the students indicated

that the “learning tool” meets their learning needs

and does not waste their time. Their understanding

of the topic was improved by using the tool. Close to

50% of the students reported that they understand

the strategy of the “learning tool” and were able to

adjust their learning in order to maximize the

advantage in using the learning tool.

3.5 Student Feedback on Intrinsic

and Extrinsic Motivation (IM and

EM)

More than 80% of the students reported that the

“learning tool” being a support throughout the

semester motivated them to use it more regularly.

This indicated that students use the “learning tool”

because they believe it is a support for the learning

in the course throughout the semester. At the same

time, 80% of the students reported that they used the

“learning tool” more seriously because it is part of

the grading scheme. Both the intrinsic and extrinsic

motivation played an important role in learning.

First, we performed an initial factor analysis to

observe the relationship among the factors and their

indicators. Some variables were well defined with a

factor (AFF1, AFF2 and AFF3 with Factor 4; PLO1

and PLO2 and PLO5 with Factor 5). However,

other items such as ATT1 loaded on Factor 1 (0.580)

and factor 2 (0.578). During subsequent factor

analysis we rotated the matrix to improve our ability

to interpret the loadings (to maximize the high

loading of each observed variable on one factor and

minimize the loading on the other factors. Scree plot

and eigenvalue were used to identify the number of

factors that can be extracted from the items pool

(Field, 2000)

Factor analysis was performed on the original set

of items, six factors were retained initially. After

factor extraction often it is difficult to interpret and

name the factors on the basis of their factor loadings.

A solution to this difficulty is factor rotation. Factor

rotation alters the pattern of the factor loadings, and

hence can improve interpretation. Thus, to obtain

better understanding of the factors, we used

orthogonal rotation which tends to maximize the

loadings on one factor and minimize the loading on

the other factor or factors. The most commonly

used rotation scheme for orthogonal factors is

Varimax, which attempts to minimize the number of

variables that have high loadings on one factor.

There are two methods: orthogonal and oblique

rotation. In orthogonal rotation there is no

correlation between the extracted factors, while in

oblique rotation there is. It is not always easy to

decide which type of rotation to take; as Field states,

“the choice of rotation depends on whether there is a

good theoretical reason to suppose that the factors

should be related or independent, and also how the

variables cluster on the factors before rotation”. A

fairly straightforward way to decide which rotation

to take is to carry out the analysis using both types

of rotation; “if the oblique rotation demonstrates a

negligible correlation between the extracted factors

then it is reasonable to use the orthogonally rotated

solution” (Field, 2000).

The EFA was performed in three steps: (1)

Unrotated on all items, (2) Rotated on all items and

(3) Rotated and refined. In step 3, refined implies

that we dropped all the items that did not meet the

inclusion criteria. Also, in each step we analyzed the

factor matrix, eigenvalues and the scree plot. Here

we present the final solution.

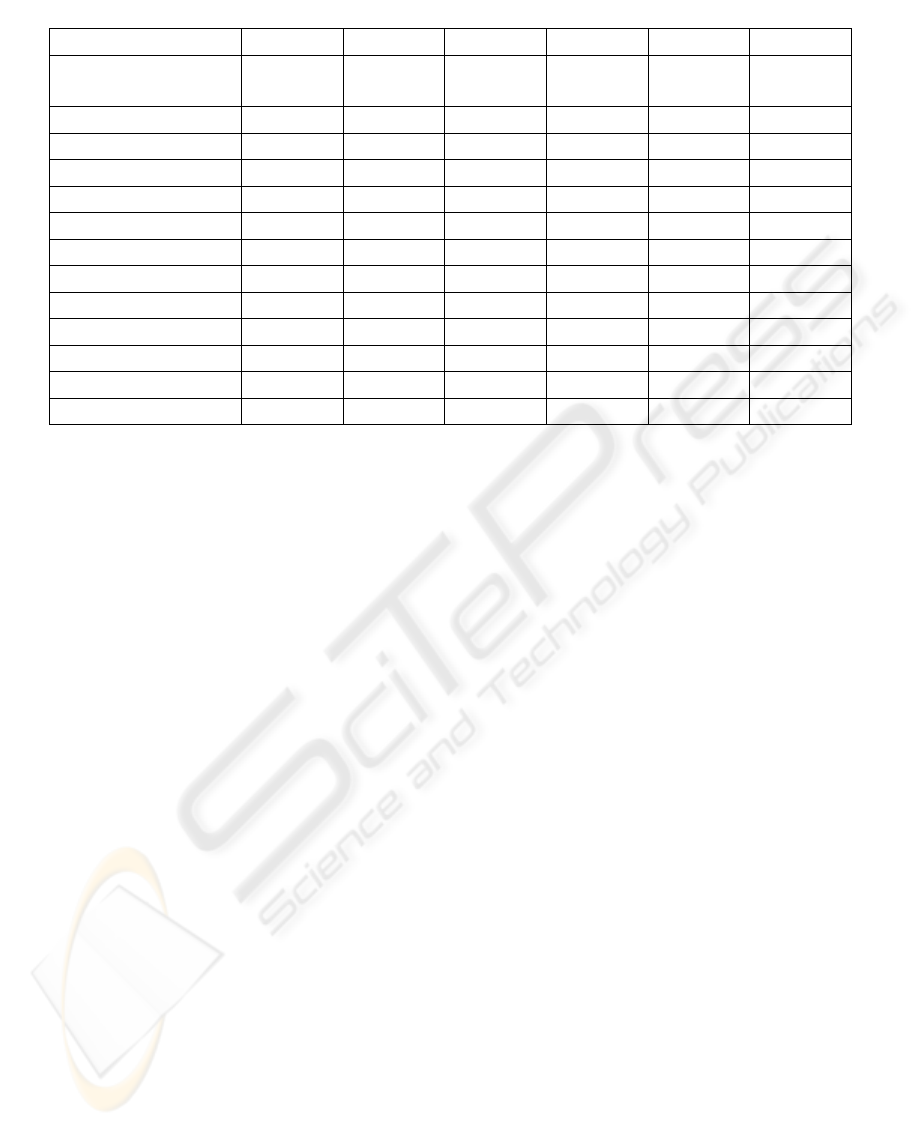

3.6 Retained Solution

Due to the low correlation and low factor loading,

the following items are rejected: AFF1, PC2, PC4,

PC5, PC6, ATT6, PLO1, PLO2, PLO4, IM1, and

EM1. After dropping these items, the final analysis

is presented. Table 1 summarizes the relationship

among the factors and their observed indicators.

WEBIST 2005 - E-LEARNING

462

Items with high values are bold to contrast the

loading on their respective factor. Items that belong

together should have relatively higher loading on the

same factor. For example PC1 and PC2 load 0.679

and 0.927 on factor 4, which are high compared to

the other variables which load 0.338 or less on the

same factor.

We can immediately see that the variables are

well defined with a factor (PC1 and PC3 with Factor

4; ATT1, ATT2, ATT3, ATT4 and ATT5 with

Factor 1; AFF2 and AFF3 with Factor 3; PLO3 and

PLO5 with factor 2).

4 LIMITATIONS

Dimensions that influence online learning have been

investigated by researcher under different

experimental traits. In this study, we gathered items

from different literature and tested the validity of

these items under the use of an online learning tool

context. We acknowledge that implications of our

findings are only confined to the limits at which we

interpret the results, and that these limitations must

be acknowledged.

From the participants’ perspective, bias with the

sample of learners may be due to the sample size,

and demographic controls. Moreover, the nature of

the course is such that it is an introductory MIS

course containing many chapters and additional

topics that we ask the students to learn. This is

especially difficult for the students who have never

been exposed to the field of information technology.

Therefore generalizing the findings in terms of

behavior and intentions to other courses and schools

may be limited. As a result, we need to identify the

boundary conditions of the dimensions as they relate

to demographic variables such as age, gender,

Internet competencies and other course properties. In

fact, the nature of the course is an important variable

that contributes to the success or failure of online

learning. In effect, some courses lend themselves to

be appropriate for online while other do not.

Similarly, some students have the skill to follow

online learning tools while others do not.

Considering the questionnaire, it is not free of

subjectivity. The respondents’ self-report measures

used are not necessarily direct indicators of

improved learning outcomes. Furthermore, although

a proper validation process of the instrument was

followed, the fact that the questions were collected

from other research may not necessarily be precise

and appropriate in the context of this study.

Conclusions drawn are based on a specific online

learning tool usage but not for all online learning

tools. Other learning tools can be designed for

different tasks and for different platforms (in this

case it was web-based) and this study was based on

a single distinct technology. This however, may not

generalize across a wide set of learning

technologies.

The effectiveness of online learning tool in

facilitating students’ learning and the learners

learning outcome are measured in many dimensions.

In this study, we chose five important dimensions

that have been investigated in different research and

tested the validities of these dimension under the

current context. These five dimensions are Affect,

Learner’s Perceived on the Course, Attitude,

Perceived Learning outcome, Intrinsic Motivation

Table 1: Factor loadings on respective items

Variable Factor1 Factor2 Factor3 Factor4 Factor5 Factor6

AFF2

0.155 0.140

-0.877

-0.050 0.122 -0.208

AFF3

0.200 0.006

-0.650

-0.200 0.035 0.147

PC1

0.282 -0.151 -0.073

0.679

0.326 0.079

PC3

0.236 -0.170 -0.095

0.927

-0.005 -0.193

ATT1 0.666

0.240 -0.182 -0.338 0.236 -0.250

ATT2 0.672

0.116 -0.083 -0.044 0.253 -0.206

ATT3 0.740

0.202 -0.185 -0.212 0.101 0.043

ATT4 0.674

0.142 -0.115 -0.100 -0.008 0.036

ATT5 0.588

0.189 -0.327 -0.214 0.431 -0.060

PLO3

0.144

-0.555

-0.086 0.098 0.297 -0.076

PLO5

0.424

-0.732

-0.143 0.123 0.367 -0.016

IM2

0.176 0.188 -0.034 -0.276 0.335

-0.574

EM2

0.119 0.250 -0.235 0.210

-0.556

-0.123

IDENTIFYING FACTORS IMPACTING ONLINE LEARNING

463

and Extrinsic Motivation. In this validating process,

all the five dimensions show content and construct

validities to some extent. The last two constructs

related to motivation should be deleted as factors if

Stevens’ (2002) guideline is followed since there is

only one loaded item for these two factors. We have

decided to retain these two factors since other

literatures indicate the importance of motivational

factors in learning (Venkatesh 1999, Venkatesh and

Davis, 2000, Venkatesh et al. 2002). The unreliable

items in constructs are eliminated and not considered

in the final solution of the factor analysis. Student

feedback on questions items and the factor analysis

provide

• validity of the dimensions that influence the

effectiveness of online learning

• controls to revalidate under different

experimental setups

• researchers with the valid questionnaire

items to test models or hypotheses under

• different contexts hence facilitating the

analysis of mediating effects on student

experiences and

• quantitative results that may help the

researcher/instructor understand the

dynamics of the online learning tool and

identify critical element to enhance the tool

in helping students perform better in their

learning process

REFERENCES

Agarwal, R., and Karahanna, E., 2000. Time Flies When

You’re Having Fun: Cognitive Absorption and

Beliefs, About Information Technology Usage. MIS

Quarterly, Vol. 24 No. 4, pp. 665-694.

Arkkelin, D., 2003. Putting Prometheus' Feet to the Fire:

Student Evaluations of Prometheus in Relation to

Their Attitudes Towards and Experience With

Computers, Computer Self-Efficacy and Preferred

LearningStyle.

http://faculty.valpo.edu/darkkeli/papers/syllabus03.ht

m (Last accessed on April 17, 2004).

Bergeron, F., Raymond, L. Rivard, S. and Gara, S., 1995.

Determinants of EIS Use: Testing a Behavioral Model.

Decision Support System, Vol. 14, pp. 131– 146.

Daley, B. J., Watkins, K., Williams, W., Courtenay, B.

and Davis, M., 2001. Exploring Llearning in a

Technology-Enhanced Environment. Educational

Technology & Society, Vol. 4, No. 3.

Davies, R. S., 2003. Learner Intent and Online Courses.

The Journal of Interactive Online Learning, Vol. 2,

No. 1.

Davis, F.D., 1989. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease

of Use, and User Acceptance of Information

Technology. MIS Quarterly, Vol. 13, pp. 319-340.

Davis, D. F., Bagozzi, R.P. Warshaw,P.R. 1989.User

Acceptance of Computer Technology: a Comparison

of Two Theoretical Models. Management science,

Vol. 35, No. 8, pp.982-1003.

Davis, F.D., Davis, G.B. and Warshaw, P.R., 1992. User

Acceptance of Computer Technology: A Comparison

of Two Theoretical Models. Management Science,

Vol. 35, No. 12, pp. 982-1003.

Deci, E L., and Ryan, R.M., 1985. Intrinsic Motivation

and Self-determination in Human Behavior. Plenum,

New York.

Eklund, J. and Eklund, P. (1996), “Integrating the Web

and The Teaching of Technology: Cases Across Two

Universities,” Proceedings of the AusWeb96, The

Second Australian WorldWideWeb Conference, Gold

Coast, Australia. Available online at:

http://wwwdev.scu.edu.au/sponsored/ausweb/ausweb9

6/educn/eklund2 (last accessed Feb, 2004).

Feenberg, A., 1987. Computer Conferencing and the

Humanities. Instructional Science, Vol. 16, pp. 169-

186.

Faigley, L. 1990. Subverting the electronic workbook:

Teaching writing using networked computers. In D.

Baker & M. Monenberg (Eds.), The writing teacher as

researcher: Essays in the theory and practice of class-

based research. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Field, A. (2000). Discovering Statistics using SPSS for

Windows. London – Thousand Oaks –New Delhi:

Sage publications.

Hair, J.F. Jr. , Anderson, R.E., Tatham, R.L., & Black,

W.C. (1998). Multivariate Data Analysis,

(5thEdition). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Irani, T., 1998. Communication Potential, Information

Richness and Attitude: A Study of Computer Mediated

Communication in the ALN Classroom. ALM

Magazine, Vol. 2, No. 1.

Krendl, K. A., and Lieberman, D. A., 1988. Computers

and Learning: A Review of Recent Research. Journal

of Educational Computing Research, Vol. 4, No. 4,

pp. 367-389.

Kum, L. C., 1999. A Study Into Students’ Perceptions of

Web-Based Learning Environment. HERDSA

ANNUAL International Conference, Melbourne, pp.

12-15.

Lowell, R., 2001. The Pew Learning and Technology

Program Newsletter.

http://www.math.hawaii.edu/~dale/pew.html (last

accessed Feb, 2004).

Marzano, R. J. & Pickering, D. J., 1997.

Dimensions of

learning (2

nd

ed.), Alexandria, VA: Association for

Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Picciano, G. A., 2002. Beyond Student Perceptions: Issues

of Interaction, Presence and Performance in an Online

Course. JALN, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 21-40.

WEBIST 2005 - E-LEARNING

464

Poole, B. J. and Lorrie J., 2003. Education Online: Tools

for Online Learning. Education for an information

age, teaching in the computerized classroom, 4

th

edition.

Richardson, C. J. and K. Swan, K., 2003. Examining

Social Presence in Online Courses in Relation to

Students’ Perceived Learning and Satisfaction. JALN,

Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 68-88.

Saadé, G. R., 2003. Web-based Educational Information

System for Enhanced Learning, (EISEL): Student

Assessment. Journal of Information Technology

Education, (2), pp. 267-277. Available online:

http://jite.org/documents/Vol2/v2p267-277-26.pdf

(last accessed Feb, 2004).

Stevens, J., 2002. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the

Social Sciences (4th Edition). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum Associates.

Sunal, W. D., Sunal, S.C., Odell, R.M. and Sundberg,

A.C., 2003. Research-Supported Best Practices for

Developing Online Learning. The Journal of

Interactive Online Learning, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 1-40.

Triandis, C. H. (1979), “Values, Attitudes, and

Interpersonal Behavior,” Nebraska Symposium on

Motivation, 1979: Beliefs, Attitudes and Values,

Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, pp. 159 –

295.

Vallerand, R. J.,1997. Toward a Hierarchical Model of

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation. Advances in

Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 29, pp. 271-

374.

Venkatesh, V., 1999. Creation of Favorable User

Perceptions: Exploring the Role of Intrinsic

Motivation. MIS Quarterly, Vol. 23, No. 2, pp. 239-

260.

Venkatesh, V. and Davis, F. D., 2000., A Theoretical

Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four

Longitudinal Field Studies., Management Science,

Vol. 46, No. 2, pp. 186-204.

Venkatesh, V., Speier, C. and Morris, M.G. 2002. User

Acceptance Enablers in Individual Decision-Making

About Technology: Toward an Integrated Model.

Decision Sciences, Vol. 33, pp. 297-316.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M.G. Davis,F.D. and Davis, G.B.,

2003. User Acceptance of Information Technology:

Toward a Unified View. MIS Quarterly, Vol. 27, pp.

425-478.

Wlodkowski, R. J ,1999. Enhancing Adult Motivation to

Learn, Revised Edition, a Comprehensive Guide for

Teaching All Adults. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-

Bass.

IDENTIFYING FACTORS IMPACTING ONLINE LEARNING

465