KNOWLEDGE NEEDS ANALYSIS FOR E-COMMERCE

IMPLEMENTATION:

People-centred knowledge management in an automotive case study

John Perkins

University of Central England, Birmingham. UK

Sharon Cox

University of Central England, Birmingham, UK

Ann-Karin Jorgensen

University of Central England, Birmingham, UK

Keywords: skills needs analysis, knowledge management, socio-technical systems, e-commerce systems, intellectual

capital

Abstract: A UK car manufacturer case study provides a focus upon the problem of aligning transactional information

systems used in e-commerce with the necessary human skills and knowledge to make them work

effectively. Conventional systematic approaches to analysing learning needs are identified in the case study,

which identifies some shortcomings when these are applied to electronically mediated business processes. A

programme of evaluation and review undertaken in the case study is used to propose alternative ways of

implementing processes of developing and sharing knowledge and skills as part of the facilitation of

networks of knowledge workers working with intra and inter-organisational systems. The paper concludes

with a discussion on the implications of these local outcomes alongside some relevant literature in the area

of knowledge management systems. This suggests that the cultural context constitutes a significant

determinant of initiatives to manage, or at least influence, knowledge based skills in e-commerce

applications

1 INTRODUCTION

Social practice acts to develop and apply appropriate

knowledge and skills to make e-commerce work as a

total socio-technical system in unique business

contexts. A knowledge management consultancy

case study project with a UK car manufacturer,

referred to here as ‘Carco’, shows how conventional

approaches to skills needs analysis (SNA) were

found to be deficient for the organisational needs at

a time of accelerated adoption of electronic

commerce systems throughout the organisation. The

paper then describes the progress and outcomes of

some facilitated workshops that sought to integrate

quality processes as part of an enhanced SNA

process. A discussion then focuses on how far

contextual factors such as departmental culture

appear to determine processes of intellectual capital

development through facilitated processes of applied

knowledge management.

2 CARCO COMMERCIAL

SYSTEMS DIVISION

During the early 1990s the Commercial Systems

Division (CSD) of Carco, a UK car maker, supplied

information system development expertise in sales,

marketing and financial areas developed new

business objectives. One was to improve their in-

house ability to manage expertise sourced from their

Associates, as employees were referred to within

Carco. Another was to provide competitive

advantage through e-commerce technology. By the

mid 1990s much of the e-commerce technical

infrastructure was in place. However, one of the

most serious issues constraining expansion

concerned the matching of personnel with

appropriate process knowledge and skills to new e-

commerce roles.

335

Perkins J., Cox S. and Jorgensen A. (2005).

KNOWLEDGE NEEDS ANALYSIS FOR E-COMMERCE IMPLEMENTATION: People-centred knowledge management in an automotive case study.

In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, pages 335-338

DOI: 10.5220/0002551703350338

Copyright

c

SciTePress

3 THE SKILL NEEDS ANALYSIS

PROJECT

The process for identifying skill shortages at this

time was embedded in individual annual

performance reviews that all employees undertook

with their line manager. A similar model is often

used for training analyses. Peterson (1998) explains

such a process when she identifies seven key stages

in training needs analysis that can be used to

represent the contemporary process at Carco. These

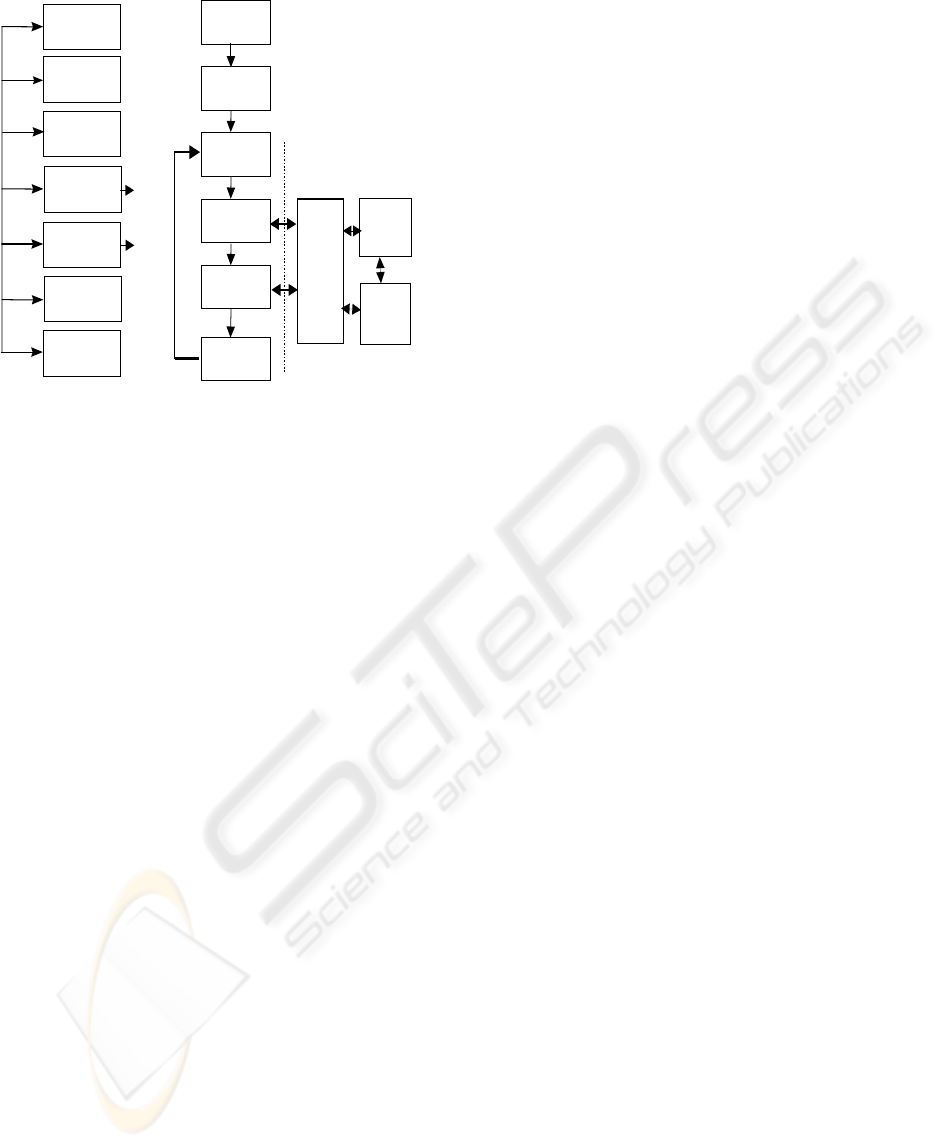

traditional stages are shown in the left side of figure

1.

Performance concerns at CSD involved the

division’s ability to deliver information system

projects through the use of a range of contractors.

Skills classifications at Carco had traditionally been

categorised as either ‘technical’, which included

competence in the use of software packages or

‘management’. Training needs identification was the

process designed to detect and specify training needs

at individual and organisational levels. They were

analysed on a corporate divisional basis to arrive at

an overall view of current divisional skills.

The analysis of training needs was the process of

examining these needs to determine how best they

might be met. The ultimate purpose was to match

the skill deficiencies found in CSD with

programmes of development already in existence

within Carco. Much of this took place within the

normal Personal Profile Development (PPD) used

within Carco. Training objectives identified specific

skilled performance that should be achieved by the

trainee at the end of the training. According to

Peterson, this systematic process of analysis and

design leads to the final stage of optimum training

design.

Quality Strategy

Corporate Plan

Business

Objectives

Skills Needs

An a l y s i s

Skills Matching

Measure and

Evaluate against

Business Plan

People

De v ’ t

Plans

People

De v’ t

Ac t i o n s

People Planning and

Development Process

1. Performance

p

roble

m

2. Performance

concern

3. Performance

objective

4. Training needs

identification

5. Analysis of

training need

6. Training

objectives

7. Optimum

training design

Discard

non -

training

p

rojects

Fi

The introduction of three critical projects led to a

need for a rapid approach to staffing these new

technology platforms. The skills analysis process

described above was seen to lack sufficient

responsiveness in this new context. The hybrid skills

identified as necessary for much of the new e-

commerce project were to depend upon lateral

communications and structured through human and

technological networks. As a result a joint project

was launched to develop improved means of

managing skills. The project was known as New

Skill Needs Analysis (NSNA). The deliverables of

the project involved the definition of the core skills

for each grouping within CSD, the collection of

actual skills data for each of the 39 CSD Associates,

establishment of skill requirements deriving from

business plans and Personal Development Reports

(PDR) identification of gap (if any) between skills

required by business tasks and actual skills and the

recommendations of how to fill these skills gaps.

The right hand diagram in figure 1 shows the

process used for the revised SNA. The next sections

explain how this process worked.

The quality strategy included empowerment of

Associates, seizing business opportunities and

bringing about continuous improvement in all

aspects of corporate endeavour. The corporate and

divisional plans set targets to achieve the overall

business strategy. Carco set out to maximise the

potential of its human resources and to leverage this

human resource with information and

communication technologies applied to supply chain

management. The NSNA project was to identify

skills and knowledge necessary to enable planned

projects and to evaluate how far skills currently

existed among Associates (Perkins and Nixey 1999).

The right hand diagram in figure 1 shows the general

process which used four sets of matrices showing

the types of skills necessary for critical job roles in

e-commerce, the level of competence required for

these skills, the level of competence currently in

place for a range of skills in a specific role and this

competence information presented by the individual

in that role (the ‘postholder’). This, in turn, was

categorised as ‘Grade’ i.e. the competence level

required, ‘Post’ i.e. the competence required as

defined by the postholder and ‘Held’: the actual

level of competence held by the postholder. The

measurement of competence levels for identified

skills used a scale developed during the workshops.

This scale was coded 0 (competence not required) to

3 (expert).

g. 1

Comparison of two processes of SNA

From Peterson (1998)

From Perkins and Nixon (1999)

Qu al i t

y

Ci r c l es

Figure 1: Comparison of two processes of SNA

ICEIS 2005 - ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEMS

336

Workshops were set up at this stage to measure

and evaluate the skills needs identified against the

business plan. It was during workshops at this stage

that skills that had previously been taken as well

understood were recognised as being in need of

much more analysis to be of practical use for

effective training or focused recruitment. In

considering means by which the emerging skill gaps

might be closed, proposals emerging from

Associates revolved around the use of short

apprenticeships, shadowing and mentoring.

Alternative proposals involving the use of external

analysts to conduct concentrated studies of practice

were met with less enthusiasm by the Associates. As

a result of this some expert practitioners in key skill

areas launched initiatives involving mentored

apprenticeships of Associates for skill development

mediated by skill councils, effectively communities

of practitioners in identified e-commerce skill areas

such as deal negotiation, technical troubleshooting

and new business development.

4 DISCUSSION

The project began as a HRM exercise, but it became

clear that the practice of conducting business

between people connected by technology networks

provide a new level of complexity. To address this,

the project became much more oriented around skills

analysis, intellectual capital development and

knowledge management.

Some lessons quickly emerged. There was a

h

eritage for treating skills as either management or

technically oriented. The need to deal with skills that

blended both of these categories meant that existing

language relating to skills became irrelevant and

often misleading (Dingley and Perkins 1999). The

processes of developing ways to use the technical

infrastructure were part of everyday work within the

small communities of Associates who were normally

members of quality circles (Chourides 2003). This

was where authentic practice was recognised and

where appropriate skills were developed and passed

on to newcomers to the community (Lave and

Wenger 1991). The requirement for rapid

implementation of the three e-commerce projects at

the time imposed urgency. Trial and error became

the main way of developing expertise. The original

quality circles were used as support groups to guide

and protect Associates. This was essentially a

mechanism for embedding intellectual assets in to

these artefacts of e-commerce, as described by

Snowden (2002).

Using Blackler’s typology (Blackler 1995)

e

mbedded knowledge in this case study was located

in the systematic routines within the structure of the

e-commerce platform that comprised application

software with the developing practice of a small

community of Associates. Embodied knowledge was

located in action, ‘know-how’ and problem solving

that depended upon intimate knowledge of the

operating situation rather than abstract rules. This

was evident in some of the expert e-commerce

practitioners. Encultured knowledge was located in

the language of shared understanding resulting from

people working closely together. It was this area that

was most problematic to Carco because the

constantly shifting boundary of participants acted to

form a wider operating community linked by a

technological network. Encoded knowledge

involved the transmission of decontextualised data

instructions as well as Carco codes of practice and

instruction manuals.

In these terms, the NSNA system at Carco

p

rovided effective intervention to manage, or at

least, influence the development of embedded

knowledge to provide greater embodied knowledge

to the Associates. The existence of encultured

knowledge was recognised and reified in Quality

Circles. However there was little use made of it as a

mechanism for recognising necessary skill bases.

The success of the NSNA project paradoxically was

gained by allowing the influence of encoded

knowledge – the technical versus managerial divide

maintained in all codes of practice – to decline. It

was to be replaced by encultured knowledge through

the increasing influence of the developing

professional community of e-commerce workers,

originally through their quality circles. These groups

developed into a council that had much greater

influence as the determiners of skill, skill gaps and

tactics to close them.

Impact assessment in November 2004

Since 1999 Carco has undergone further changes

of o

wnership. This period has seen further increases

in competition and increased pressures to innovate in

operation and design alongside severely limited

access to capital investment. In their annual accounts

published in October 2004 Carco declared a loss of

£70 million, but pointed out that this was 10% of the

loss recorded in 1999 and looked forward to

international collaborative projects to close this

trading gap in the following year.

During this period the division had been re-

or

ganised and restructured, but the cultural

movements towards a more distributed approach to

skills needs recognition and process knowledge

management are recognisable in studies of recurrent

practice in Carco’s commercial operations.

KNOWLEDGE NEEDS ANALYSIS FOR E-COMMERCE IMPLEMENTATION: People-centred knowledge

management in an automotive case study

337

5 CONCLUSIONS

A single instance of skills management in e-

commerce has been used to illustrate some of the

dynamics of how organisational context can

influence the implementation of what are often seen

as primarily technical systems. The principal

outcomes are firstly that the categorisation of

knowledge types provides an alternative and useful

reorientation to traditional ways of thinking about

how specific organisation contexts might constrain

e-commerce and other technology project

development. Secondly, skills are often not generic.

In this case they were highly specific to a particular

set of operating conditions. In these circumstances a

new taxonomy of skills need to be constructed by

those who have access to encultured knowledge

necessary to socialise and externalise this tacit

knowledge (Nonaka et al 2000).

Returning to the point made at the beginning of

th

e paper, this case study illustrates the rapidly

changing context of modern business, where e-

commerce is employed. Critical success factor in e-

commerce involves the people who develop and use

it, the knowledge and skills that they can

individually bring to these systems and the extent to

which they can form communities that cope with

needs to change practice. But it is not sufficient to

simply agree this as a corporate policy – its

implementation needs to be a fundamental and

integral part of an e-commerce strategy, and

dedicated processes and procedures need to be

developed to provide such implementation. The

centrality of real-world working practice and

associated knowledge in developing communities

provides a starting point for what might be called

knowledge, or k-Commerce. The approach is more

generally supported by work in social practice

theory, especially in the area of informal learning

(Eraut 2000).

There is considerable research work needed in

th

is area. There is some interesting work taking

place in the field of social practice theory, which

focuses on the study of work culture through the

analysis of professional practice. This provides a

reorientation of knowledge as an objective resource

into ‘knowing’ as attribute of doing work. This

paper makes a small contribution to this work but

more research is needed, applied to specific

instances of e-commerce and broader socio-technical

practice.

REFERENCES

Blackler, F. (1995) Knowledge, Knowledge Work and

Organizations: an overview and interpretation.

Organization Studies, 16, 6, 1021-1046.

Brown, J.S. and Duguid, P. (1996) Organisational

Learn

ing and Communities of Practice: Towards a

Unified View of Working, Learning and Innovation,

in: M.D. Cohen & L.S. Sproull (Eds.) Organisational

Learning, Sage Publications.

Chourides, P., Longbottom, D. and Murphy, W. (2003)

Excellen

ce in Knowledge Management: An empirical

study to identify critical factors and performance

measures, Measuring Business Excellence. Bradford:

Vol.7, Iss. 2: p.29.

Davies, M. and Hakiel , S. (200

0) Knowledge Harvesting:

a practical guide to interviewing, Expert Systems, Vol.

5, no.1, February, p.42.

Dingley, S. and Perkins, J. (1999) ‘Tempering Links in th

e

Supply Chain with Collaborative Systems’, in:

Proceedings of the Conference on Business

Information Technology Management: Generative

Futures, Hackney, R. (Ed.), Manchester Metropolitan

University, UK, November, MMU Press, Manchester.

Eraut, M. (2000) Non-formal learning and tacit knowledge

in professional work,

Journal of Educational

Psychology, Vol. 1, Part 1, pp. 113-136.

Lave, J. and Wenger, E. (1991) Situated Learning:

Legit

imate Peripheral Participation, Cambridge

University Press.

Mager, R.F. (1988) Making Instruction Work or

Skillbloomers, Lake, Belmont, CA, USA. pp. 29-42.

Nonaka, I., Toyama, R. and Konno, N. (2000) SECI, Ba

and Leadership

: a Unified Model of Dynamic

Knowledge Creation, Long Range Planning Vol. 33

pp.5-34.

Peterson, R. (1998) Training

Needs Assessment, Kogan

Page: London.

Snowden, D. (1998) A framework for creating a

sustainable knowledge mana

gement programme. In

The Knowledge Management Yearbook 1999-2000,

Cortada, J.W. ,Woods, J.A. (Eds). Butterworth-

Heineman, Boston, MA.

Wenger, E. (1998) Communities of Practice, Cambridge

Univers

ity Press.

ICEIS 2005 - ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEMS

338