CROSS-DOMAIN MAPPING: QUALITY ASSURANCE AND

E-LEARNING PROVISION

Hilary Dexter, Jim Petch

The e-Learning Research Centre, University of Manchester186 Waterloo Place, Manchester, United Kingdom

Keywords: e-learning provision, quality assurance,

checklist, process model, knowledge domain

Abstract: In order to ensure that a valid and robust model of e-learning provision is developed it has to be based on a

thorough understanding of the e-learning provision domain. The fullest and most detailed articulations of

the e-learning development process are found in quality checklists for e-learning development. The problem

this paper addresses is that posed by the situation of having knowledge used for modeling in one domain

represented by artifacts in another. Using a number of checklist sources, a composite list was developed for

some aspects of the e-learning development process. The checks address the activities and their artifacts that

should be monitored, and what the outcomes of the checks should be in terms of what actions should be

taken and what changes made if the results do not meet quality criteria. A small worked example of this

cross-domain mapping process is given.

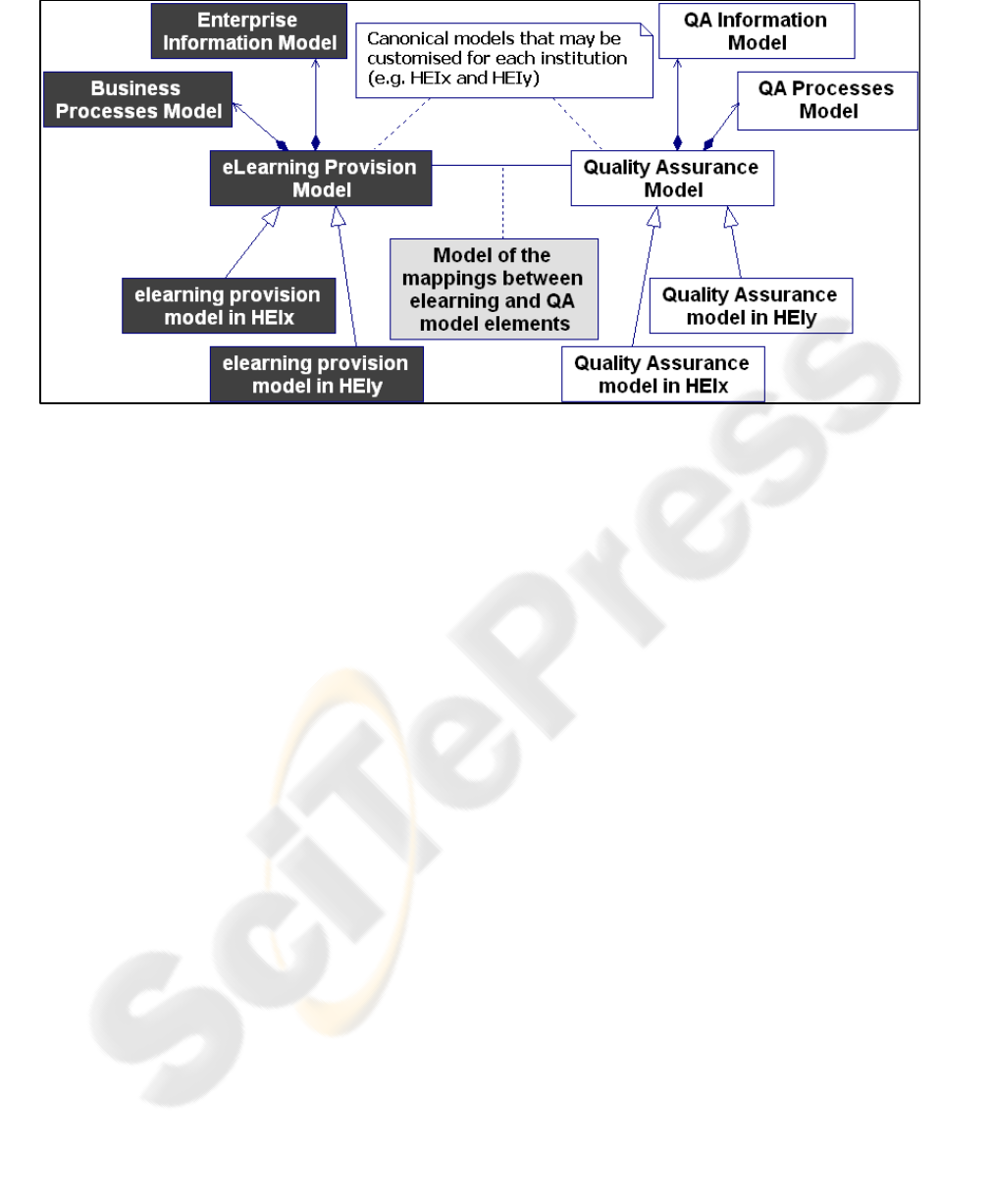

1 CONTEXT

The stimulus for this study is the need to ensure

quality service provision for e-learning in higher

education, viz. the processes of planning, design,

development and delivery of e-learning courses.

Underlying the study is an approach to service

provision based on enterprise models. The e-learning

provision model is seen as part of an enterprise

model that includes business processes and

enterprise information model as well as the

provision of e-learning by partner institutions

(Figure 1).

The main premise of this study is that in order to

ens

ure that a valid and robust model of e-learning

provision is developed it has to be based on a

thorough understanding of the e-learning provision

domain. There are two challenges here. One is that

there is no thorough articulation of the e-learning

provision domain that is in any way comprehensive.

The second is that there are very few published

accounts of quality on which to base a model.

Almost all Higher Education (HE) provision is in

situations that are not adequately documented and

the few available commercial sources are

understandably thin.

In fact the fullest and most detailed articulations

of t

he e-learning development process are found in

quality checklists for e-learning development. It

seems that a number of organizations and

individuals have used this means of expression as a

way of capturing and organizing knowledge about

the domain (Scienter-MENON 2004,WCET 2000).

Studies of some of the most widely used and

wel

l known checklists (Hirumi 2003, Franklin,

Petch, Armstrong and Oliver 2004) show clearly that

the scope of these checklists differs substantially and

that the nature of the checks themselves is not

consistent. However it is possible to rationalize the

available checklists (Petch 2003, 2004) so that a

consistent and comprehensive description of the e-

learning development and delivery process is

achieved.

Recognizing that the development of checklists

i

s an ongoing process, a set of published lists was

used to develop a consolidated and harmonized list

that could be used as the basis for developing an e-

Learning Provision model. In this study the list does

not cover the complete e-learning development cycle

(Wilcox, Petch and Dexter, 2004) but is sufficient

for the purpose of exploring the cross-domain

mapping issues.

2 PROBLEM

The problem this paper addresses is that posed by

having knowledge used for modeling in one domain

represented by artifacts in another. It is the problem

199

Dexter H. and Petch J. (2005).

CROSS-DOMAIN MAPPING: QUALITY ASSURANCE AND E-LEARNING PROVISION.

In Proceedings of the Seventh Inter national Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, pages 199-205

Copyright

c

SciTePress

of cross-domain mapping. It is necessitated by the

fact that the best available knowledge of the e-

leaning process is in the Quality Assurance (QA)

domain but the model needed to be developed is in

the provision domain. In fact, in practice there are

iterations of interaction between these domains, and

in some organizations a reasonable expectation that

they have been planned together, so that we may

expect some alignment between them. However,

there remains the problem for the modeler of

developing a satisfactory meta-model and a valid

model in one domain from knowledge based on the

meta-model and model in another. There is no

intention here of modeling the QA domain. The

checklists are taken as given.

The problem of cross-domain mapping is put

forward as a general one for domain modeling. It is

suggested that the situation of asymmetric

positioning of knowledge and model is

commonplace. Indeed a cross-domain mapping

approach may be a useful element of a modeling

strategy in general.

3 APPROACH

A modeling approach has been adopted to tackle the

transfer of knowledge between the two domains of

interest. A modeling framework has been set up to

provide an environment in which it will be possible

to progress in iterations of modeling activity towards

a complete and precise expression of all the people,

processes and technology involved in the provision

of e-learning services. The modeling framework

includes an evolving well-defined vocabulary of

modeling elements expressed in the Unified

Modeling Language (UML).

Figure 1: Modeling the Quality Assurance (QA) and the eLearning Provision domains

A domain model describes the elements that can

exist in the domain, their interrelationships and their

types. Both the static and dynamic aspects of that

domain need to be represented in the model, that is

both the data and information entities and the

business processes. The UML domain model

comprising Classes, Relationships, Use Cases,

Activities and States is equivalent to a formal

ontology for that domain, taking the definition of an

ontology as being “an explicit formal specification

of how to represent the objects, concepts and other

entities that are assumed to exist in some area of

interest and the relationships that hold among them”

(International DOI, 2005). UML may be extended

by stereotypes and tagged values if required to

define precisely concepts in the domain (Fuentes and

Vallecillo, 2004) thus negating the need for a

separate and different ontology language. The

extended UML elements are packaged together into

what is termed a UML profile. In this way an e-

learning profile for UML can be constructed and

added to as more information about the domain is

gathered. This profile may then be applied to any

modeling effort concerned with e-learning provision.

The domain model for e-learning provision

being developed in this research program employs

Class Diagrams, Activity Diagrams and Use Case

ICEIS 2005 - SPECIAL SESSION ON EFFICACY OF E-LEARNING SYSTEMS

200

Table 1: Knowledge Areas Covered by Checklists

ORGANIZATION ACE:

American Council on

Education 1997

AFT:

American Federation of

Teachers 2000

ADEC:

American Distance

Education Council 2004

INSTITUTIONAL

GUIDELINES

o Organizational

Commitment.

o Encourage

experimentation

o Administrative &

organizational

commitment.

PROGRAM DESIGN

AND CURRICULUM

GUIDELINES

o Learning Outcomes

o Technology

o Class size

o Student assessment

o Full programs

o Evaluation of

Coursework

o Technological and

human infrastructure.

COURSE DESIGN

AND

PEDAGOGICAL

GUIDELINES

o Outcomes

o Content

o Expectations

o Interactions

o Assessment

o Complement

Elements

o Technology

o Activities and

assessments

o Potentials of medium

o Personal interaction

o Courses materials

o Outcomes and objectives

o Learner engagement

o Media Use

o Learning environments

o Learning experiences

o Social mission

STUDENT AND

ACADEMIC

SUPPORT

GUIDELINES

o Learner Support o Student requirements

o Advisement

o Research opportunities

o Learner Support

FACULTY

SUPPORT

GUIDELINES

o Academic control

o Faculty Preparation

o Materials Control

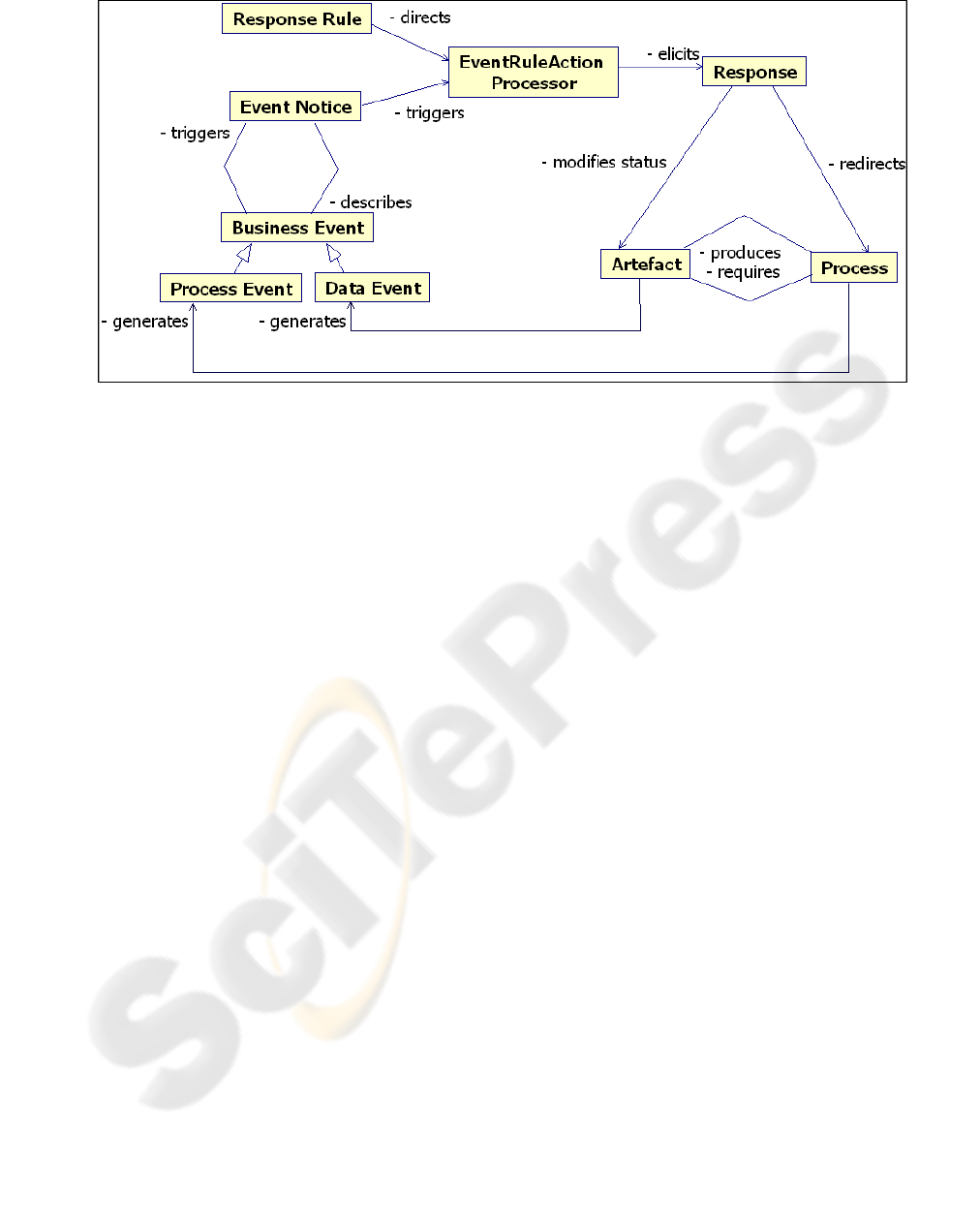

Diagrams as a useful subset of the range of tools

available in the UML. The Activity Diagrams

include the flow of artifacts in the domain, and their

state at any stage in the process may be included in

the model. In this way the lifecycles of significant

artifacts, such as proposals, strategy documents,

course materials etc, may be captured in the context

of the activities that require or produce them.

Concepts, such as monitoring and evaluation and

response to events (see Figure 5) are often best

represented in Class Diagrams where the elements

concerned and their interactions can be depicted.

The business rules such as those for determining the

appropriate response to events or for decisions in

workflows are captured as constraints.

4 CHECKLISTS

Checklists are the result of a non-formal synthesis of

knowledge of the domain. Tables 1 and 2 based on

Hirumi (2003), illustrate the knowledge areas some

of the widely used checklists represent and show the

variety in scope and nature of the checklist areas.

These lists were developed by a variety of processes,

few of which were fully documented but include

surveys of practice, expert submissions, team

brainstorming and formalizations of working

practices. Using these major sources, a composite

list was developed for some aspects of the e-learning

development process. A sample of the composite is

presented in Table 2. The style of checks varies

significantly. Some are checks that represent points

of principle, some are on approach, some on

activities undertaken and some are instructions about

what to do. The sample in Table 2, and the type used

in this study are of the style that relate to activities

undertaken and objectives achieved. In the

composite checklist an attempt has been made to

keep consistent checks that relate to activities and

objectives.

The process of consolidating the various

checklists consists of an iterative amalgamation and

breakdown of the various activities represented by

the checks. By iteratively cross-checking checks it is

possible gradually to extend the scope of the

subjects checked and to avoid repetition. By

CROSS-DOMAIN MAPPING: QUALITY ASSURANCE AND E-LEARNING PROVISION

201

iteratively considering groups of checks it is

possible, on first principles, to assess the

completeness of the scope and the continuity of the

processes.

Table 2: Sample Section from Checklist for E-Learning

Development, University of Manchester

QA Checklist for Project Management

Pre-Planning

Has a structured approach been adopted?

Have roles and responsibilities been defined?

Has a communication protocol been agreed?

Has documentation been agreed?

Project Control

Does the project have an external assessor?

Has an evaluation, monitoring and feedback

system been set up?

Do you have a system for Change

Management?

Project Exit

Have the deliverables been accepted?

Have you decided how to measure whether the

deliverables

have been achieved?

Are there any remaining to be achieved at a

later stage?

How will you assess what lessons have been

learnt?

How will the final costs be calculated?

How will you assess if the benefits have been

achieved?

Also by iterative composition, and based on cues in

the original checklists, it is possible to develop a

structure to the checking process that represents

stages or components of a viable e-learning

development process. For each of the checks and

stages it is possible from some of the checks and

from first principles to associate actions and artifacts

elsewhere in the enterprise.

5 CROSS-DOMAIN MAPPING

There exists a two-way interaction between the QA

domain and the e-learning provision domain that

may also be captured by the evolving model.

Processes in these two domains interact with each

other and influence each other. QA may be viewed

as an “Aspect” of the e-learning domain that may be

modeled as a system running alongside and

impacting on the e-learning provision system.

In turn, as the domain model for e-learning

provision evolves, new checks will be discovered

that may be added to the checks repository. Gaps not

covered by checks may be identified in the QA

process and redundancies may be highlighted. Other

factors such as which checks are critical and whether

there is any bias in the checks may also be

illuminated by the act of modeling the e-learning

provision domain and capturing practices.

Checklists tell us which things in each stage of a

business process, activities and their artifacts should

be monitored, and what the outcomes of the checks

should be in terms of what actions should be taken

and what changes made if the results do not meet

quality criteria. This information allows us to build a

model of the business process itself.

A small worked example of this cross-domain

mapping process is given here using checks

available from an internal source (Petch, 2003) and a

few external sources (Frances and Bonora, 2004,

Kelly, 2004, QAA 1999). Figure 2 shows the top

level activity diagram for one section of the e-

learning provision model process.

Figure 2: Activity Diagram for Preparing a New Course

Proposal for Review.

This section covers the stages between a faculty

board approving a preliminary proposal for a new

course and requesting a detailed “New Course

Proposal” in order to execute a “New Course

Review” and the New Course Proposal being ready

for that review. The group (role) responsible for

carrying out these activities is referred to as the

“Course Team”. A checklist appropriate for this

stage in e-learning provisioning provided the

knowledge about the existence of the role of an

approving body. In many institutions this would be a

faculty board but in others it may not. In the latter

case the checklist may be indicating what roles

ICEIS 2005 - SPECIAL SESSION ON EFFICACY OF E-LEARNING SYSTEMS

202

another body may have to take on in order to carry

out the approval process. The checklists have also

guided the sequencing of the steps and in some cases

contain the prerequisites for activities.

The checks from multiple lists are managed in a

repository where they are given a logical

organisation based on the 15 identified practice areas

within the e-learning lifecycle (Dexter and Petch,

2003).

Figure 3: The Practice Areas in the e-Learning Lifecycle

Activities from these practices are executed at

various times during the lifecycle of a product such

as an “e-learning course”. For management

purposes, the whole lifecycle is divided into phases

and each phase is divided into a number of iterations

depending on the complexity of the product being

developed. In each iteration there are a number of

activities from the practices and the iteration

produces a set of deliverables.

The checklist items for the activity Market

Analysis, from the Activity Diagram in Figure 2, are

found in the “Business Analysis and Planning”

practice (Figure 3). Checks were modeled as Classes

and Figure 4 shows the internal structure of a check

(attributes and operations) and its relationship to the

e-learning lifecycle.

There are two ways to build on the e-learning

domain model from the checklists:

1. Adding a hierarchy of activities that matches

the checklist items by using subactivity states,

drilling down from the top level activity

diagram and adding object flow states to link

artifacts (documents, software applications, e-

learning materials, technology) to the

activities. These are artifacts required or

produced by the activities.

2. Creating a Use Case for the activity. Each Use

Case may then be expanded to describe the

workflow and outputs in detail. The Use Case

will also specify its preconditions, i.e. the

activities that have to have been completed

prior to its execution. Each Use Case may then

be expanded to describe the workflow and the

outputs in detail.

Figure 4: Structure of Checklist Item

The following table (Table 3) shows the

activities discovered in checklists relating to

“Market Analysis” that would be relevant to the

stage in the process shown above, “Preparing New

Course Proposal”.

Table 3: Activities Identified for Market Analysis

Market Analysis Activity

Determine brand identity

Identify markets and the elearning segments

Determine the positioning of the course

Calculate the size of potential markets

Assess trends in potential markets

Assess ease of access to potential markets

Assess the nature of the competition

Determine the market share of other producers.

Create strategy for acquiring and analyzing market

information

Set up system for monitoring and evaluating needs of

students and alumni

Determine the long-term potential of the course

Identify the sales channels for the course.

Determine whether price is a determining factor

Discover which courses have done well recently and

why (also poorly)

Review possible changes in government policy that

may affect demand

Discover the key success factors in this market

When the course team reaches the stage in the

preparation of the New Course Proposal of “Market

Analysis” it will be able to see the expanded set of

activities recommended. The team should execute

the activities and then use a checklist from the

CROSS-DOMAIN MAPPING: QUALITY ASSURANCE AND E-LEARNING PROVISION

203

Figure 5: Events and Rules Governing Processes

repository to ensure that it has covered all the areas.

The relevant checks are found in the checklist

repository by the activity “Market Analysis” itself,

by means of a subscription mechanism (see section

6). Each of the activities inside “Market Analysis”

may also have subscribed to checks and these can be

made available to the course team as they execute

the activity Operationalization.

The model shown above (Figure 5) of the event

response governing process is based on a simplified

version of the event-driven process and data-event-

driven process models provided in the EDOC UML

profile (OMG, 2004).

This model decouples the events generated by

an activity or artifact in the business process from

the set of responses to that event by using a publish-

and-subscribe mechanism. In this way any activity

or artifact in the system can subscribe to a set of

checks and respond to them appropriately. Any

event in the system, generated by an activity or an

artifact can publish, in an event notice, the need for a

set of checks and these will be picked up by those

processes that have subscribed to the event. Their

response to the checks is contained in the “Response

Rule”. This response could be in the form of a new

set of activities in a process and/or the repetition of

activities that have already been executed.

This mechanism allows a reservoir of checklist

items to serve multiple processes, with checklist

items being used in different places in ways

determined by the Response Rule which will be

appropriate for the context.

6 E-LEARNING SERVICES

PROVISION

e-Learning service provision can be driven by

executable business process models by adopting

mechanisms based on the Business Process

Execution Language for Web Services (BPEL4WS)

(Kath, Blazarenas, Born, Eckert, Funabashi and

Hirai, 2004). Such mechanisms will collect the

services and components in the environment, both

technology-based and people-based, and

choreograph them into a service aligned with the

defined task.

In order to get closer to the quality of model

required for such a venture we need to be able to

acquire extensive, in-depth knowledge about the

processes. The models must also be provided to

institutions in a way that they may be customized for

the organization. One means to improve the depth of

knowledge in the domain model is shown to be by

interacting with the QA domain and to learn from

QA checklists.

7 CONCLUSION

We have argued that cross-domain mapping can

form part of an enterprise modeling strategy for e-

learning provision. We have demonstrated a proof of

concept for the process of cross-domain mapping

and have provided a model of a mechanism to

operationalize the use of checklists for governing the

provisioning process in e-learning.

ICEIS 2005 - SPECIAL SESSION ON EFFICACY OF E-LEARNING SYSTEMS

204

The next steps in the work are a fuller

development from the proof of concept to a rich e-

learning model based on the combined checklist set.

At the same time, the checklists should be refined as

we are able to take a whole system view. The

checklist operationalization mechanism should be

implemented and tested over a range of situations

where checks give rise to modified activities in

multiple parts of the e-learning provision processes.

REFERENCES

Dexter, H., Petch, J., 2003. A Roadmap for e-Learning

Service Provisioning, e-Learning Research Centre,

research paper,

http://www.elrc.ac.uk/publications/163/

Frances, V.L., Bonora, A.G., 2002. Methodology for the

Analysis of Quality of Open and Distance Learning

Delivered via the Internet (MECA-ODL)

www.adeit.uv.es/mecaodl

Franklin, T, Petch, J., Armstrong, J., Oliver M., 2004. An

Effective Framework for the Evaluation of E-

Learning, eLearning Research Centre, research paper

http://www.elrc.ac.uk

/publications/153/

Fuentes, L., Vallecillo, A., 2004. An Introduction to UML

Profiles, UPGRADE , European Journal for the

Informatics Professional 5,2,

http://www.upgrade-

cepis.org/issues/2004/2/

upgrade-vol-V-2.html

Hirumi, A., 2003. In Search for Quality: An Analysis of e-

Learning Guidelines and Specifications, submitted to

the Journal of e-Learning Administration

International DOI (Digital Object Identifier) Foundation,

2005. Glossary,

http://www.doi.org/

handbook_2000/glossary.html

Kath, O., Blazarenas, A., Born, M., Eckert, K.-P.,

Funabashi, M., Hirai, C., 2004. Towards Executable

Models: Transforming EDOC Behavior Models to

CORBA and BPEL, Proceedings of the 8th IEEE Intl.

Enterprise Distributed Object Computing Conference

Kelly, B., 2004. QA Focus Handbook, JISC

QA Focus Project

www.ukoln.ac.uk/qa-focus/

documents/handbook

Object management Group (OMG), 2004. UML Profile

for Enterprise Distributed Object Computing

Specification,

http://www.omg.org/

technology/documents/

modeling_spec_catalog.htm

Petch, J., 2003. Quality Assurance for New Courses, e-

Learning Research Centre, working paper,

http://www.elrc.ac.uk/publications/162/

Petch, J., 2004. QA Checklists, e-Learning Research

Centre, briefing paper, http://www.elrc.ac.uk

/publications/162/

Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA),

1999. QA Distance Learning Guidelines

www.qaa.ac.uk/public/dlg/contents.htm

Scienter-MENON Network (ed), 2004. Sustainable

Environment for the Evaluation of Quality in E-

Learning (SEEQUEL)

http://www.education-

observatories.net/seequel/SEEQUELTQM

_Guide_for_informal_learning.pdf

Western Cooperative for Educational Telecommunications

(WCET), 2000. Guidelines for the Evaluation of

Electronically Offered Degree and Certificate

Programs

http://www.wcet.info/resources/accreditation/

guidelines.pdf

Wilcox, P., Petch, J., Dexter, H, 2004. A Foundation for

Modelling e-Learning Processes, e-Learning Research

Centre, working paper,

http://www.elrc.ac.uk/publications/148/

CROSS-DOMAIN MAPPING: QUALITY ASSURANCE AND E-LEARNING PROVISION

205