Using Reputation Systems to Cope

with Trust Problems in Virtual Organizations

Marco Voss and Wolfram Wiesemann

IT Transfer Office

Darmstadt University of Technology

Darmstadt, Germany

Abstract. The concept of virtual organizations (VO) denotes a relatively new or-

ganizational approach. It should allow especially small- and medium-sized firms

to rapidly cooperate by forming ad-hoc organizations in order to exploit busi-

ness opportunities that would otherwise not be manageable for the participants

alone. VOs will span enterprise and national boarders. This paper addresses the

trust problem inherent in virtual organizations and proposes reputation systems

as a solution which already proved functionality in many domains of computer

science. We finally present a reputation system for VO marketplaces that pays

special attention to the privacy requirements specific to this scenario.

1 Introduction

Modern information technology provides the opportunities for new inter enterprise inte-

gration concepts like virtual organizations. Referring to [1–3] we define a virtual organi-

zation to be a temporal alignment of (globally dispersed) multiple organizations, com-

bining the complementary core competencies of its participants in an ad-hoc network-

like structure to produce and deliver customized demand, which the individual partic-

ipants cannot produce and deliver individually, by exploiting modern information and

communication technologies (ICT). The concept of virtual organizations is especially

interesting for small- and medium-sized companies. It opens new business opportuni-

ties primarily by offering possibilities to effectively specialize on core competencies

(thereby allowing to gain competitive advantages in certain areas), causing synergetic

effects by the combination of those core competencies and allowing to exploit business

possibilities that are not manageable for a single company.

However, there are also significant threats linked to this concept: Customers usually

prefer a single company being liable for products and services. Well established brands

have major influence on purchase decisions. Severe trust problems may arise in such

structures and superior managerial skills and tools are needed for setting up and running

VO’s [4, 5].

This paper focuses on the trust problem just mentioned and proposes the usage of

reputation systems as one possible solution. The concept of virtual organizations itself

suggests that many issues between the cooperating partners can’t be settled by means of

ex ante contracts, be that because of time restrictions (remember that rapidly exploiting

Voss M. and Wiesemann W. (2005).

Using Reputation Systems to Cope with Trust Problems in Virtual Organizations.

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Security in Information Systems, pages 186-195

DOI: 10.5220/0002573201860195

Copyright

c

SciTePress

business opportunities is one of the main goals of VO’s) or because of the fact that

complete contracts (i.e., contracts specifying actions for all possible states of the world)

are infeasible (at least in the case of VO’s). Organization Theory, Incomplete Contract

Theory and Game Theory have given us interesting insights into those situations. One

of the solutions proposed by those theories is inducing trust by the usage of reputation

information. Reputation systems are already used in many areas of computer science

to solve similar problems. They provide information as the basis of a trust decision

and give a continuous motivation to behave trustworthily. We will present a reputation

system that makes use of cryptographic techniques to meet the privacy requirements of

a VO scenario. Most current approaches to implement reputation systems completely

neglect privacy aspects. In our scheme reputation information is controlled by its owner

and it stays hidden who has submitted the feedback.

The paper is structured as follows: We start with a scetch of a possible lifecycle of

a VO in Section 2. This lifecycle will be used as a tool for illustration purposes in the

following chapters. Section 3 discusses the usage of reputation systems and presents

our reputation management approach. Section 4 finally concludes our work.

2 Lifecycle of a Virtual Organization

In the following we will concentrate on a simple, idealized lifecycle for virtual organi-

zations; this model is used in the following sections to discuss how processes have to

be adapted in order to provide reputation-based trust. We divide the lifecycle into three

characteristic phases of a virtual enterprise, namely the foundation phase, the operation

phase and the liquidation phase. Those three phases will be briefly presented in the next

few subsections; we finish this chapter with a small example practically illustrating our

lifecycle model.

2.1 Foundation Phase

The main result of the foundation phase is a network of independent firms (a virtual or-

ganization) that is willing to deliver a product or service (in the following abbreviated

by ”good”) to a customer. However, one should keep in mind that regarding the foun-

dation of a virtual enterprise as a distinguished phase is idealized: Usually the network

will evolve and continually change throughout the production process – new business

partners might get involved whereas others drop out (due to finishing their part of the

contract or not obeying the rules of the contract). As a consequence there is no sta-

tic network but a steadily changing web of relations between the participating firms.

Nevertheless this assumption simplifies further reasoning and as we’ll see our approach

(applying a reputation system to induce trust among the parties) does not rely on a clear

separation of the different phases.

This organization has furthermore settled (by means of a contract) on a set of trans-

actions that should take place inside the network (e.g. certain parts of the good are

delivered, money is paid etc.) and between the network as a whole and the customer

(the final good is delivered to the customer). We will discuss this set of transactions in

the next subsection.

187

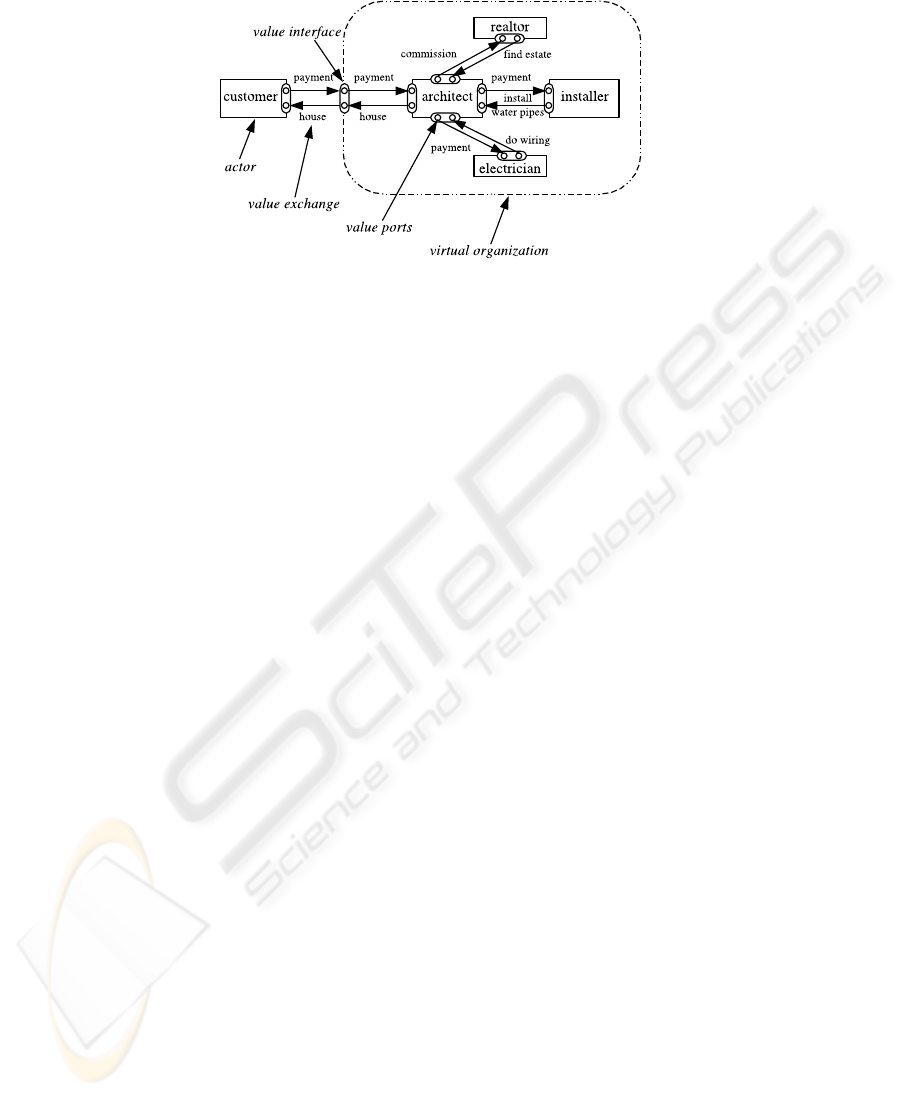

Fig.1. E

3

Value Decomposition Methodology.

How does such a network evolve, i.e., how do customers and virtual organizations

meet, and how do business partners meet in order to establish a network? It seems

reasonable to expect some kind of marketplace to address this issue; in fact this topic is

already under investigation [6]. However, many questions still remain unanswered: Do

for example customers ask for certain goods (pull-approach), are they offered by virtual

organizations (push-approach) or will a combined approach be taken? Furthermore, are

virtual organizations founded by a business integrator (a distinguished party with a

coordinating role establishes a VO by searching for business partners and negotiating

with them; pseudo-hierarchical approach), or are they founded on a peer-to-peer basis?

The complexity increases further if one considers nested virtual organizations, i.e. VO’s

where business partners founding the enterprise might theirselves be virtual, too. In fact

a huge variety of different approaches seem plausible, nevertheless these aspects are

out of the scope of this paper – for the sake of applying a reputation system we can

safely assume that parties (i.e., customers and virtual organizations on the one hand and

business partners that form a VO on the other hand) ”somehow” meet by means of the

marketplace.

2.2 Operation Phase

During the operation phase the product or service is produced by the members of the

virtual organization. The expected exchanges taking place in the operation phase can

be conveniently visualized by the e

3

value decomposition methodology [7, 8]: Briefly

summarizing the most important elements for our topic, we can distinguish between

actors, value objects, value ports, value interfaces and value exchanges. Actors are the

business partners forming the virtual organization; they are exchanging value objects

(e.g. products, services or money) in processes called value exchanges. For receiving

or sending value objects every actor has a certain amount of value ports; the set of all

value ports of an actors is called value interface.

However, for the purpose of our paper a small enhancement will prove helpful: the

set of actors forming a virtual organization will be enclosed by a dashed circle. As in

188

business processes single points of entry are the norm, the virtual organization itself gets

its own value interface; the value ports act as an abstract port hiding the encapsulated

actors inside the enterprise. The concepts just explained are visualized in Figure 1.

2.3 Liquidation Phase

At the end of the operation phase the final good is delivered to the customer, thereby

fulfilling the contract between customer and VO. As a result the virtual organization is

liquidated.

Again we have to note that the assumption of a possible clear distinction between the

phases simplifies reality: Up to now it still seems to be uncertain when exactly virtual

organizations are liquidated: Does this happen when the good is delivered or when all

possible liabilities are sorted out? At first glance one might think that only legal entities

(and not the virtual organization as a whole) should be held liable – however customers

probably don’t want to be confronted with the internals of the virtual organization (in

fact the business partners might have an incentive to hide their relationships, too). Put

in other words, at least for the customer the VO still exists (or has to be recoverable) for

liability and support issues. (This leads to problems as soon as some of the companies

originally forming the VO do not exists anymore.)

3 Applying Reputation Systems to VO Marketplaces

The goal of this chapter is to discuss how trust can be induced among partners in the

context of virtual organizations by means of a reputation system. We start by briefly

summarizing the development of reputation systems in computer science. Afterwards

we show what needs to be done in order to apply a reputation system in a VO market-

place (with focus on the lifecycle processes described in Section 2). Finally we present

a reputation system that uses cryptographic techniques to meet the privacy requirements

of a VO scenario.

3.1 Reputation Systems in Computer Science

Reputation systems [9] collect, aggregate and distribute feedback about an entity’s for-

mer transactions. Feedback is usually collected at the end of each transaction. The au-

thority responsible for reputation management asks the participants to submit a rating.

Aggregation of feedback means that the available information about an entity’s trans-

actions is evaluated and condensed into a few values that allow users to easily make

a decision. Feedback finally is distributed to the participants, i.e. it has to be made

available to everyone who wants to use it for making decisions on whom to trust.

Applications of reputation systems range from electronic marketplaces, peer-to-peer

networks, virtual and agent societies to more exotic areas like wearable communities.

eBay’s feedback system [10] is a famous example of a working reputation system. It is

often stated that the feedback system plays a crucial role in their success story (empirical

experiments [11] have shown that a seller’s reputation in fact significantly increases the

buyer’s willingness to pay auction price premiums).

189

Although the variety of existing reputation systems in computer science is huge,

they are all based on the three principles explained above. However, many variations

are possible: Feedback can for example be collected, aggregated, and distributed in a

centralized (i.e., a single server is responsible for reputation management) or distributed

fashion. The later is often the case in peer-to-peer networks. In this context distribution

usually takes place by ”gossipping”. Furthermore, many variations of feedback aggre-

gation are discussed nowadays (e.g., how should different values be aggregated, to what

extend do old feedback values play a role etc.). Schlosser et al. [12] give an overview

of different aggregation algorithms.

[13] discusses the role of privacy in reputation systems. Reputation information can

contain sensitive private data that allows detailed profiling. eBay’s feedback report for

instance, contains not only the received ratings but also links to the auction details. Thus

it is visible to everybody what you have bought or sold. The context of a rating (e.g.

information about the traded goods or used services) and the transaction partner should

not be disclosed in every situation. Especially in a VO scenario the business partners

of a company can represent a valuable secret for competitors. Additionally, an entity

should have control over its own reputation information to prevent profiling.

3.2 Reputation Systems in the Context of Virtual Organizations

This subsection discusses how the processes explained above have to be changed in

order to support reputation management. The adaptation of the VO lifecycle turns out

to be very straightforward: The participating parties have to make a trust decision in the

foundation phase. Reputation information will support this decision. Reputation only

plays a minor role in the operation phase, and the liquidation phase is enhanced by the

process of giving mutual feedback. We will now briefly discuss those adaptations.

We will now relate the two concepts of trust a reputation by integrating them into

what we call the trust decision: Imagine two marketplace participants A and B (e.g.

a customer and a business integrator or two business partners), that don’t know each

other, have the possibility to engage in a business transaction in the foundation phase.

They have to decide whether they want to engage in a transaction at all (participation

decision) and – if this is the case – how much monitoring will be needed during the

operation phase, how the conditions of the contract should be designed etc. (cover de-

cision). As those decisions are based on trust, we refer to them in their entirety as trust

decision. A rational agent will base this decision on the information he either already

has or can get (for reasonable cost). Reputation plays an important role here as it says

something about how the transaction partner has performed in the past. This is espe-

cially true on a marketplace with a huge number of participants, because the propability

to meet the same partner again is low. Without own experiences one has to rely on

judgements made by others.

The operation phase is not only characterized by the production processes, but also

by continuous monitoring of the involved business partners. Although reputation does

not directly support the monitoring process, it gives valuable information on how much

monitoring might be needed (i.e., partners with very good reputation values might not

need to be monitored to the same degree as new marketplace participants) and gives

190

strong incentives for all parties to behave honestly (because of the above-mentioned

shadow of the future).

Finally, the parties involved in a virtual organization (i.e. the end-customer and all

participating business entities) will be asked to give feedback about the other entities’

behavior in the liquidation phase. This feedback will be aggregated and distributed,

thereby helping other parties in the foundation phase.

3.3 Credential-Based Reputation System

This subsection presents our proposal for a reputation system that fulfills the privacy

requirements mentioned above. We first talk about the parties involved in that system.

Afterwards we discuss who has the right to rate whom. Obviously only parties that

somehow interact with each other should have the right to give feedback about the other

party’s behavior. Finally, we show how the rating process and reputation distribution can

be implemented in a secure and privacy-preserving way.

Involved Parties The reputation system we envision consists of three different types

of involved parties:

– End-Customers and Business Partners: Those are the entities that actually have

a reputation. In the following we will assume that the business partners forming

the VO are represented by a single VO administrator (in the following abbreviated

by VOA). This is automatically the case in VO’s that have a business builder (the

business builder is the VOA). Peer-to-peer style VO’s, however, are not necessarily

represented by a single VOA – for ease of notation (and without limitation of gen-

erality) we consider them to internally sort out issues and speak with a single voice

in the protocol below.

– Marketplace Controllers (MPC): As already discussed in 2, we assume inter-

actions between end-customers and possible VO’s on the one hand and business

partners possibly forming a VO on the other hand to take place in a marketplace

environment. The MPC is the authority running this marketplace. We don’t expect

a single universal marketplace to evolve – rather multiple marketplaces will pre-

sumably exist simultaneously.

– Reputation Authorities (RA): Running the reputation system is not necessarily

done by the MPC – rather an RA may offer this service to several marketplaces.

However more than one RA might be established, too, so that transferability of

reputation from one RA to another becomes a crucial issue.

Rating Permissions Reputation values represent aggregated feedback, i.e. they con-

sist of a bunch of feedbacks given by the agents a party interacted with in the past. A

company participating in VO’s can get feedback from other companies he forms VO’s

with (giving information about whether he behaved honestly in the VO) and from end-

customers (informing whether the VO as a whole delivered on time and with reasonable

quality).

191

We propose to use the e

3

value decomposition methodology as explained in Section

2 for determining who has the right to rate whom. Obviously only parties that interacted

with each other in some way should have the right to do so. Accordingly, every value

object deliverance arrow implies a backward rating permission arrow. There are two

exceptions to this rule: First, we do not deal with the question whether end-customers

should receive feedback or not, since our focus are VOs. The second exception is caused

by the VO value interface: If more than one VO company is linked to this interface

(peer-to-peer style VO), the feedback of the end-customer should affect all companies

connected to the interface. However, this would imply that those customers have greater

influence on reputation which doesn’t seem to make sense – we propose that in this

case the feedback is normalized (i.e., if n companies are connected to the interface,

each individual feedback gets a weight of

1

n

– note that all individual feedbacks are the

same, though, as end-customers just rate the VO as a whole, not the individual parties

forming the VO). However, how the collected reputation information is interpreted by

an entity is out of scope of this paper.

Implementation To ensure that the identity of a rater cannot be linked to the rating we

use the following cryptographic building blocks:

Anonymous credentials [14] allow an authority to issue rights to a user in such a

way that the receiver can prove possession of a credential to other authorities without

making the issuing and multiple demonstrations of an anonymous credential linkable

to each other. Showing such an credential preserves the anonymity of its owner. One-

time or one-show credentials can be used exactly once. Blind signatures schemes [15]

allow to sign a document without revealing it’s contents to the signer. For illustration

one can imagine to put a document with a piece of carbon copy paper into an envelope

(blinding). The signer signs the envelope on the outside. The envelope is removed by

the receiver of the signature afterwards (unblinding procedure). Result is a signature on

a document the signer has not seen before. A partially blind signature allows the signing

entity to encode some fixed data into the signature that is still available after unblinding.

This can be used to encode some additional attributes into the signature. For simplicity

reasons we do not give any further technical details here.

We start our following description with the rating protocol that is executed in the

liquidation phase: The single steps of this protocol are the following (see also figure 2):

1. The administrator of the VO registers with the marketplace controller (MPC). De-

tails about the participants and their relationships (i.e., the structure of the VO) are

communicated. Note that this has to take place anyway (also if we would not use

a reputation system) as private marketplaces will probably take transaction fees or

something similar. Furthermore the structure of the VO has to be known for liability

and tax reasons.

2. (In the following we assume that A gets feedback from B, i.e. A is target of a rating

and B acts as a rater.) B requests a credential from the MPC that contains the right

to submit a rating for A. The MPC checks if there is an according relationship in

the registered VO and issues a credential and a signed context object that contains

192

Ratee A Rater B MPC RA

register VO

VOA

request rating credential

credential, context object

transact

prove credential possesion

submit blinded context object and rating

create partially

blind signature

blinded signed rating

unblind

signed rating

Fig.2. VO Entity Rating Process

some details about the context of this relationship (e.g. the type of service and

values concerned)

1

3. A and B interact with each other and with other members of the virtual organi-

zation. Monitoring is used both to assure the other partners deliver in time and to

collect information as a basis for a later rating.

4. B wants to submit a rating for A. Therefore, it contacts the reputation authority

(RA) via an anonymous channel and proves the possession of a credential that

allows to rate A.

5. B blinds the rating and the context object and transfers both to the RA.

6. The RA uses a partially blind signature function to sign the blinded information. In

the non-blinded part the identity of the rating’s target (i.e. A) is encoded. To ensure

integrity and non-repudiation of A’s ratings RA increments A’s total of received

ratings. RA returns the signed data to B.

7. B verifies the signature and unblinds the contained information.

8. Finally, the signed rating is returned to A. (If B wants to hide its identity it uses an

anonymous channel.) The signed rating consists of the context object and the rating

value, but it contains no information about the rater B. Additionally, MPC and RA

are not able to link this information to B.

Now that we know how parties receive feedback, we can explain how an entity A

shows its reputation to an entity C in the foundation phase: A does so by disclosing the

list of collected ratings. As we know from above this list contains no information about

the raters of A (this is important in order to preserve privacy). C checks the signatures

of the single ratings and assures integrity of this listing by asking RA for the number of

1

To prevent that the MPC encodes some additional (side channel) information into the context

object, that can be used to identify the rater, the allowed types and values should be well

specified.

193

issued ratings. As an offline alternative RA can issue short-lived certificates that contain

the number of ratings a ratee has received. If this number is bigger than the number of

entries in the list C may assume that A tries to hide some (negative) ratings. However,

what happens if B cheated A in step 8 by not forwarding a received signed rating? If A

recognizes such a case she can try to find out whose rating is missing and then contact

B for clarification. If this is not possible because the system uses anonymous channels

to hide raters, there should be no real incentive for B to do so since there is no reason

to fear discrimination.

Transferring reputation between reputation systems is easy because A keeps all re-

ceived ratings with her. The only requirement is that the source reputation authority is

accepted to be trustfull.

Ismail et al. [16] propose a similar reputation system but do not use blinding tech-

niques to prevent the reputation authority from learning the contents of a single rating.

Additionally, the RA stores all submitted ratings and creates a certificate containing the

processed reputation information. This means that the target of a rating has no control

over its reputation information.

4 Conclusion

It’s seems to be commonly agreed that the concept of virtual organizations will play a

crucial role in the future, especially for small- and medium-sized firms. However, for

this to become reality some problems still have to be fixed; a major issue seems to be

the lack of trust between partners engaging in VO-type businesses. In this paper we

proposed the use of reputation systems to alleviate this trust problem. This seems to be

a reasonable approach as reputation systems have already proved effectiveness in many

application domains. Privacy is an aspect neglected by many existing approaches. The

presented reputation system places special emphasis on the rater’s privacy and gives the

owner control over his reputation information. Nevertheless, there is a need for further

refinements; for example how customer’s ratings are evaluated. In our approach the

structure of the VO must be known to the MPC. This allows the MPC to gain much

valuable knowledge and therefore leads to another trust problem: Can business partners

completely trust in the honesty of the MPC? We will have to investigate those problems

further.

References

1. Wolters, M.J.J., Hoogeweegen, M.R.: Management support for globally operating virtual

organizations: The case of klm distribution. In: Proc. of the 32th Hawaii International Con-

ference on System Sciences (HICSS 32). (1999)

2. Duklis, P.S.: The joint reserve component virtual information operations organization (jrvio);

cyber warriors just a click away. Technical report, U.S. Army War College and Carlisle

Barracks and Pennsylvania (2002)

3. Koehler, T., Lattemann, C.: Corporate governance in virtual enterprises – networks of trust?

In: Proc. of the eBRFConference. (2004)

4. Lee-Kelley, L., Crossman, A.: Will you still love me tomorrow? Trust in the virtual organi-

zation. In: Proc. of the Human Resources Global Management Conference. (2001)

194

5. Robinson, P., Haller, J., Kilian-Kehr, R.: Towards trust relationship planning for virtual or-

ganizations. In: Proc. of the Second International Conference on Trust Management. (2004)

6. Barbini, F.M.: Fairwis: A virtual organization enabler. In: Proc. of the International

Workshop on Open Enterprise Solutions: Systems, Experiences, and Organizations (OES-

SEO2001). (2001)

7. Gordijn, J., Akkermans, J.: Designing and evaluating e-business models. IEEE Intelligent

Systems, special issue on e-business 16 (2001) 11–17

8. Gordijn, J., Akkermans, J.: Value-based requirements engineering: Exploring innovative

e-commerce ideas. Requirements Engineering Journal 8 (2003) 114–134

9. Resnick, P., Zeckhauser, R.: Reputation Systems. Communications of the ACM 43 (2000)

45–48

10. N.N.: ebay homepage (2004) http://www.ebay.com.

11. Resnick, P., Zeckhauser, R., Swanson, J., Lockwood, K.: The value of reputation on ebay: A

controlled experiment. In: Working Paper for the June 2002 ESA conference, Boston. (2002)

12. Schlosser, A., Voss, M., Br

¨

uckner, L.: Comparing and evaluating metrics for reputation

systems by simulation. In: Proc. of the Workshop on Reputation in Agent Societies (RAS

2004). (2004)

13. Voss, M.: Privacy preserving online reputation systems. In Deswarte, Y., Cuppens, F., Jajo-

dia, S., Wang, L., eds.: Proc. of the 3rd WOrking Conference on Privacy and Anonymity in

Networked and Distributed Systems (I-NetSec04). (2004)

14. Camenisch, J., Lysyanskaya, A.: An efficient system for non-transferable anonymous cre-

dentials with optional anonymity revocation. In: Advances in Cryptology - Eurocrypt 2001.

(2001)

15. Chaum, D.: Blind signatures for untraceable payments. In: Proc. of Crypto’82. (1982)

16. R. Ismail, C. Boyd, A.J., Russel, S.: Strong privacy in reputation systems. In: Proc. of the

4th International Workshop on Information Security Applications (WISA). (2003)

195